GENTLEMEN, LET ME FREE YOU FROM A BURDEN, THE BURDEN of the history you think you know.

We have all been done a great disservice. We have been taught what I call the statue version of history. By this I mean that we have been taught a version of history that presents the heroes of the past as moral giants who fell flawless from the womb, who achieved fame almost effortlessly. It hasn’t served us well.

No one meant to do damage. Our history teachers probably thought they were simply honoring the great men and women of our past. Yet most of them gave us statues rather than human beings, unscarred giants who achieved and conquered as though there was never any question of their destiny.

It isn’t so. Hear me. It is a lie.

The great heroes of the past you’ve grown to admire were all pitiful human beings whom we remember only because they declared war on some part of their pitifulness. If we don’t know this, we are left to believe that some people are destined to be great but most of us aren’t, and those of us who aren’t should just settle down to our duties and shelve whatever dreams make our hearts race.

I’ll say it again. It’s a lie.

God sets destinies in heaven, but those destinies have to be hammered out on earth one arduous minute at a time. We strain. We bleed. We grieve. We have to conquer each step. No one gets a pass. No one moves to the head of the line, even if he gets a statue. Everyone is flawed.

Listen. John Wesley was a great man. He founded the Methodist church and helped lead England in a transformative spiritual renewal. He was a great man.

Yet his marriage was so bad that when a friend went to pick him up for a meeting, the man found Wesley’s wife dragging the great preacher around the house by the hair. The woman pretty much despised her husband. Sometimes she went to his preaching meetings—to heckle him! I’m not exaggerating a bit when I tell you that Methodist and non-Methodist historians alike have concluded that one of the reasons John Wesley rode tens of thousands of miles to preach the gospel throughout the British Isles was that he didn’t want to go home.

Here’s another example. Try to figure out who this next man is: He was a great man. One of the greatest. And yet, he was in debt every day of his adult life. His marriage was often troubled. One of his children committed suicide. He once made a decision that threw his entire country into economic turmoil. He was, for a long period, the most hated political figure in his nation. Even when he was the leader of that nation, he refused to spend the night in a room with a balcony. Why? Because he suffered from horrible bouts of depression and he never knew when another episode might strike. He feared that one day the darkness would come for him and he would try to jump to his death.

Quite a tormented person, right? You wouldn’t want this man mowing your yard—you don’t want a suicidal guy with a lawnmower around your house! But I’m talking about Winston Churchill, the greatest leader of the twentieth century.

Why don’t we teach important details like this—the whole truth about great leaders—in our schools? Wouldn’t it help kids with problems—which is to say, all of them—understand that they can achieve, too; that they aren’t irreparable misfits because they have a few challenges?

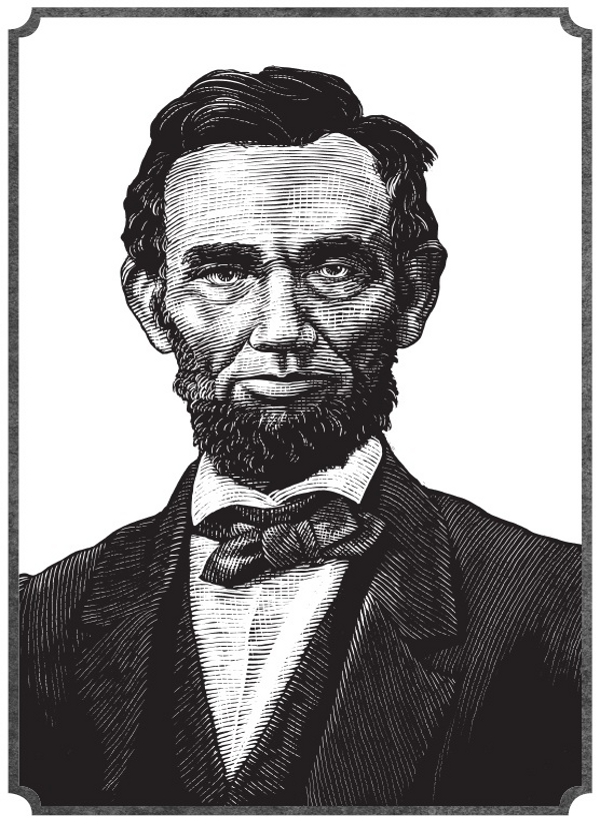

Churchill wasn’t alone. One of the greatest men in American history, Abraham Lincoln, also fought depression and was also suicidal upon occasion, at least in the first half of his life. It didn’t change the fact that Abraham Lincoln was a great man, perhaps the greatest of our presidents.

His best friend said he dripped melancholy as he walked. Another close friend said Lincoln had the saddest face he ever saw. Lincoln once wrote, “I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth. Whether I shall ever be better I cannot tell; I awfully forbode I shall not.”33

Grief haunted him all his days. A younger brother died when he was a small child. His mother died when he was nine. Abe helped his father make the casket and lower her body in the ground. His sister died when he was sixteen, and the first—and, some historians suspect, the only—woman he ever loved died young too. He buried two sons and as president felt the deaths of hundreds of thousands in the war he could not prevent nor bring quickly to a close.

He was haunted all his life by the thought of rain falling on graves.

He was not merely sad from time to time. He was chronically, manically depressed. He called it “the hypo.” It was short for hypochondriasis, the term in his day for a number of syndromes, including depression. His friend Joshua Speed said that Lincoln once “went Crazy as a Loon.” Friends had to “remove razors from his room—take away all Knives and other such dangerous things—it was terrible.”34

Lincoln considered suicide so often he even wrote a poem about it. Just a few verses reveal the darkness that tormented his soul.

Here, where the lonely hooting owl

Sends forth his midnight moans,

Fierce wolves shall o’er my carcass growl,

Or buzzards pick my bones. . . .

Yes! I’ve resolved the deed to do,

And this place to do it:

This heart I’ll rush a dagger through

Though I in hell should rue it!

Sweet steel! Come forth from out of your sheath,

And glist’ning, speak your powers;

Rip up the organs of my breath,

And draw my blood in showers.

I strike! It quivers in that heart

Which drives me to this end;

I draw and kiss the bloody dart,

My last—my only friend!35

Keep in mind that Lincoln was a lawyer and a member of the Illinois state legislature at the time.

His sadness often spilled over despite himself. He once wrote these words to a young girl he knew.

To Rosa—

You are young, and I am older;

You are hopeful, I am not—

Enjoy life, ere it grows colder—

Pluck the roses ere they rot.36

The child had merely asked Lincoln to sign her autograph book. He couldn’t stop himself. He was engulfed in misery.

Yet Lincoln did not surrender to this darkness. He changed. He grew. He deepened in faith and learned to silence the voices of death that came to him in the night. He overcame, and later helped the nation do the same.

What we most need to know about Lincoln’s battle with depression is it helped to make him a better man—not the depression itself, but rather what was produced in Lincoln as he fought back against the depression.

He learned to master his thoughts. It helped to give him a disciplined mind. He learned to reach for tactics to dispel his gloom. It helped to give him his famous sense of humor. His depression forced him to view life almost as an outsider. This gave him perspective and graced him with the poetic sense we hear in his magnificent speeches.

More than one historian has made the point that as agonizing as Lincoln’s struggle with depression was for him, it nevertheless gave us the Lincoln we know.

This is one of the great truths of life. Great men suffer greatly in order to be great. Heroic men must first endure heroic struggles with themselves. I’ve never read about a great man or woman of whom this was not true.

This is about more than Lincoln, though. It is about you and all the men you know. We know our flaws—at least most of them. We constantly face our weaknesses and our damage. It can cause us to doubt we will ever live an exceptional life. It isn’t true. If history is any guide, struggling manfully against our deformities is the beginning of greatness.

I believe most men make peace with their defects. They accept their flaws as simply the way they are, and so they never declare war on those parts of themselves that keep them from exceptional lives. Mediocrity becomes their lot in life; merely getting by their only hope.

The question we all face is not whether or not we have defects. We do. Every one of us. The question is whether we are capable of envisioning a life defined by forces greater than the weight of our flaws. The moment we can—the moment we can envision a life beyond mere compromise with our deformities—that is the moment we take the first steps toward weighty lives.

Manly men know themselves, work to understand their God-ordained uniqueness and their unique brand of damage, and accept they will always be a work in progress, always be a one-man construction project that is never quite finished in this life. They don’t despair. They don’t settle. They don’t expect perfection of themselves. They understand that destiny is in the hand of God. They also understand that these destinies are fashioned in a man’s struggle against the enemies of his soul.