IT IS OFTEN SAID THAT MEN ARE EMBARRASSED BY THEIR EMOTIONS, that they find feelings complex and messy. There is some truth to this—for some men, some of the time. The truth, though, is that for most men emotions simply aren’t primary. Men feel, but their feelings don’t usually come first for them. They have emotions, but their emotions come after other factors in importance. This doesn’t make them heartless. It also doesn’t mean they lack healthy emotions. And it certainly doesn’t mean their sometimes stoic ways make them better than women, or better than other men whose feelings are more at the surface.

This does explain, though, why much of Christianity, and much of what society wants men to do, can seem to them like a game of “emotion management.” It may also explain why we are losing men from the church and from frontline roles nationwide.

We would look at this dynamic carefully. It is the reason most men’s ministries, therapy groups, retreats, books, and even small groups fail. Someone somewhere wants men to feel something different and then act differently. They want men to manage their emotions as the path to managing their behavior.

It probably won’t happen. And it doesn’t have to.

Here’s why: men are more likely to feel after doing than they are to feel their way to doing. It’s how they are made. It’s fine, really. In fact, this order of feelings in relation to action can be a far more productive arrangement than the other way around.

Let’s look at an example. Consider the issue of forgiveness. In most churches and therapy groups, men are taught that forgiving is largely about feeling differently toward someone who has offended. We must kneel, ask God to forgive us for being such hard-hearted beings, and determine instantly to have different thoughts and emotions regarding a person who has wronged us. I believe this makes a demand that is both unwise and unbiblical. It may be the reason that many people find it so difficult to forgive and instead end up holding on to offenses their whole lives.

The truth is that forgiving is more about doing than feeling. Forgiving is primarily a decision to treat a wrong in the same way we cancel the debt of someone who owes us money. We no longer hold the debtor in a debtor’s prison. We forgive the debt by deciding we are no longer owed anything: an apology, an opportunity to beat the offender to death, the right to talk nasty about him or her. Instead, we decide—not feel—the record is wiped clean. We refuse to speak ill of the one who has harmed us. Instead, we act kindly toward them. We speak positive words, change behavior, refuse to make excuses, even go to the offender/debtor and do whatever reconciliation and restored friendship demands.

Forgiveness is about doing. It is far more than wrestling emotions in secret. We act. And, in time, the feelings come. It rarely works the other way around.

I have a friend who is a dynamic leader and a fiery Christian. He takes the command to “bless your enemy” seriously. If he reads something negative about himself in the paper or if he hears that somebody has spoken ill of him, he’ll say out loud to several of us, “No, he shouldn’t do that! I’m gonna have to bless him. See? See what this dude is makin’ me do? I’m gonna have to pour some good on his boney backside and love on him. Here it comes. Oh no! He’s not ready for this.”

My friend then writes a check to the pastor who spoke ill of him, or does something kind for the reporter who told lies about him. Let me tell you what happens then. My friend gets bigger in spirit. Most of the people who thought they didn’t like him end up becoming his friends. But no one sits around waiting for feelings to land. They just act. All the feelings come, but later, after the doing is done. And usually the winner is the kingdom of God. It’s amazing to see.

This same truth applies to men and humility. The most important aspect of being humble isn’t that we feel a certain set of emotions. The most important matter is that we humble ourselves—do deeds of humility—as a lifestyle, trusting that genuine humility will come from the “outside in” as the Holy Spirit honors our obedience.

So this is what striving for humility looks like in my life. I defer to other men. I submit to my elders. I try not to praise myself to others. I fail. I repent. I confess. I fast, in part, to live fully aware of my own weakness. I open my heart to rebuke when friends and leaders see something amiss in my life. I also submit to my wife, not only because the apostle Paul urged mutual submission of husbands and wives in his letter to the Ephesians, but also because I recognize her superior gifts. I try to see myself as small in my own eyes. I give up certain rights. All these things I do in pursuit of humility no matter how I feel at the time. Frankly, I do not often “feel humble.” I have, though, been making progress in humility by humbling myself—that is, doing deeds of humility.

This approach gets closer to the heart of a man. He is made to do first. Feelings come later—if at all. And thank God for it. Where would we be if the men who have shaped our world waited to feel before they acted?

Certainly, a man who is whole is able to feel and he should hope to have a rich emotional life. Yet a man who is whole also does not regard feelings as a mandate for action. He acts as a mandate for feeling.

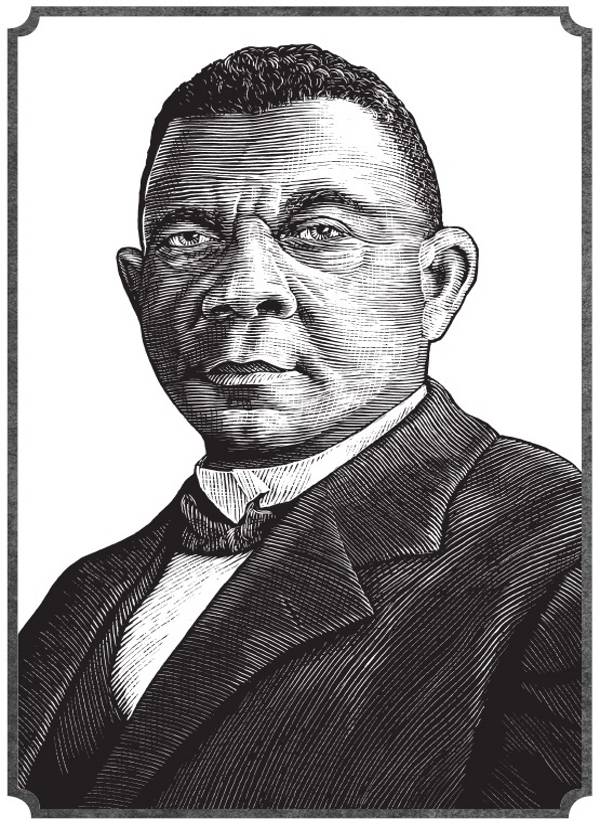

Few men have modeled the deeds of humility quite like the man in the story I’m about to tell you. During the first decade of the last century, an older woman decided to sit for a moment in the lobby of an elegant Des Moines hotel. She was weary and parched. She turned to a slender, well-dressed black man who was standing nearby and asked him to fetch a glass of water for her. The man immediately went to the front desk of the hotel and returned with the water. Handing it to the woman, he asked, “Ma’am, is there anything else I can get for you?” The woman said there wasn’t and the man walked off.

I know this doesn’t sound like that important a story. What I have not told you is that the man was, at that time, the most famous black man in the world. He was the president of a prestigious institute. He had once dined with the president of the United States. He was an advisor to kings and prime ministers and he was an internationally renowned author. Yet when a tired woman mistook him for a waiter because of the color of his skin, he took no offense. He did what she asked, and then he offered to do more. It was an extraordinarily humble act, but it was typical of this man. His name was Booker T. Washington, and the humility he displayed that day was just the brand of humility he had been urging upon his people and his nation for years.

It was Theodore Roosevelt who had invited Booker T. Washington to dine in the White House. Afterward, Roosevelt wrote:

To a very extraordinary degree, he combined humility and dignity; and I think that the explanation of his extraordinary degree of success in a very difficult combination was due to the fact that at the bottom of his humility was really the outward expression, not of a servile attitude toward any man, but of the spiritual fact that in very truth he walked humbly with his God.44

Booker T. Washington’s gracious act in that Des Moines hotel lobby flowed naturally from the course of his life. He was born to a slave woman on a Virginia farm in 1856. A census taken a few years later listed him as “1 Negro Boy (Booker)–$400.” He lived through the horrors of the Civil War with his mother, Jane, and at war’s end moved with her to Malden, West Virginia. It was there he became an employee of Viola Ruffner, a demanding New England schoolteacher who gave him his first lessons in responsibility. In later years, he attributed much of what he became to her influence.

He attended Hampton Normal School, a unique institution built on the idea that the greatest need of freed slaves was character, not charity. It was not a message most African Americans embraced at the time. Booker absorbed this philosophy into his core, graduated from Hampton as a star student, and, after teaching there for a season, moved to Alabama to open a newly chartered school with the name Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute.

The school became the vehicle for Booker’s bold, controversial philosophy. He believed character, cleanliness, industriousness, skill, godliness, and patience would mean advancement for black America. If blacks made themselves valuable to whites, equality would come. Guided by this promise, Washington designed Tuskegee to teach trades from brickmaking to typing, restore the priority of character, and imprint the values of Christianity upon the souls of his students.

He believed unearned wealth would harm his race and leave them forever an underclass. He was certain that “habits of thrift, a love of work, economy, ownership of property, bank accounts” would lead to his people’s ascent. It was the message he preached to the nation and the guiding principle of his work at Tuskegee.

Many blacks, like Harvard scholar W. E. B. DuBois, disagreed. They felt keenly the wrongs done to them by white society and looked to political processes and social aid as the sources of black advancement. They trusted in laws more than markets, in courts more than the kindly intentions of white America.

At the heart of Booker T. Washington’s vision for blacks was confidence in the power of humility. He agreed with William Mountford, who wrote, “It is from out of the depths of our humility that the height of our destiny looks grandest.”45 Washington was no coward and did not think humility the best posture of his people because he feared another course. Instead, he believed humility won the favor of God, caused a man to live simply and genuinely rather than merely to impress, and freed him from vanity so he could know himself and know the world as it was, rather than as he wished it to be.

Washington knew the temptation of the freed slave. Having been subjugated for so long, it was natural for a man just liberated from his chains to live for pleasure, excess, and a resentful type of ostentation. Booker T. Washington taught that ex-slaves who lived like this merely fashioned new chains for themselves—chains of the soul and the spirit, chains of debt and materialism. He believed he had been sent as something of a prophet to urge his people toward a higher path.

History may conclude that he was wrong about many things. He certainly overestimated the kind intentions of white society. Some whites hate blacks just for their skin color, no matter how gifted and productive and polite those blacks might be. This truth, dawning upon Booker late in life, was a heartbreaking tragedy for him.

Yet he was certainly right about the value of humility in a man’s life. In this he was prophet to men and women of all races and colors. That he died in 1915—just as the United States was stepping into a bloody European war and a movie entitled The Birth of a Nation portrayed blacks as criminals and the Ku Klux Klan as liberators (and was shown in Woodrow Wilson’s White House!)—signaled how urgently the dawning century would need Booker T. Washington’s message. It was an age with no ear to hear, though, and so it became the bloodiest, most tragic century in history. Yet, there—before it all began—was Booker T. Washington, urging simple lives, productive lives, righteous lives, each permeated by the humility Mr. Washington had shown in that Des Moines hotel.

Booker T. Washington has much to teach us as men. The powerful force of humility is certainly the greatest among them. His brand of humility was, as President Roosevelt had said of him, not the fruit of fear or insecurity. It came, instead, from a yearning to know the world in truth and to live a genuine life, freed from blinding vanity, impoverishing materialism, and burdensome debt.

Yet Mr. Washington also taught that doing humility is the path to being humble. Do humble deeds, he taught, and a humble heart will follow. This is good news for modern men striving to be manly men. Character is not out of our reach. It is not a lifelong battle to organize our emotions. Instead, it is a decision to act and to act consistently, knowing that emotions are usually a result and not a cause.

How liberating this is. A man can say to his son as men can say to each other, “Go be humble,” and the words require no need to manage feelings. Just do what is right; do what is humble. God will see and work in you to see his will complete.

Act, my friends. Do. It is the way of men.