WE HAVE COME FAR ENOUGH IN THIS EXPLORATION OF MANHOOD for you to form one of the most important conclusions about your life as a man. You are called to sacrifice. There just isn’t a way to say it any more clearly. Genuine manhood, manly manhood, true manhood—is sacrifice. To do manly things, tend your field, make manly men, and live to the glory of God—in other words, to fulfill all the Manly Maxims—you have to sacrifice.

Sacrifice what? Everything. Anything. Not your integrity or morality or commitments to God, but certainly your comforts, your rights, your time, your money, your attention, and your energy. You have to sacrifice the priority of yourself.

I’ve tried in this book to use the example of men in history rather than the statements of Scripture, simply because I want you to experience manhood by example rather than by precept. Yet consider the power of something the apostle Paul said. He told men to “love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25 NIV). Much of this is a mystery we will be trying to understand and live out all our days. One thing is certain: we are to give ourselves up. Just as Jesus did for his church. Dying to save her. Dying to rescue her. Dying to present her pure to her God. That, gentleman, is the calling of a man.

Isn’t it interesting that the stereotype of a modern man is exactly opposite this? You’ve seen this stereotype played out on the screen. The man is all about himself. His food, his hobbies, his addictions, his deformities, and his vanities dominate his life and the lives in his family. He is one big black hole of self, a giant suck hole of self-interest.

This is too often true of men; but it isn’t what they are called to be. Let me tell you a story that will move you with how a man lived out sacrifice. It will astonish you and may change how you live.

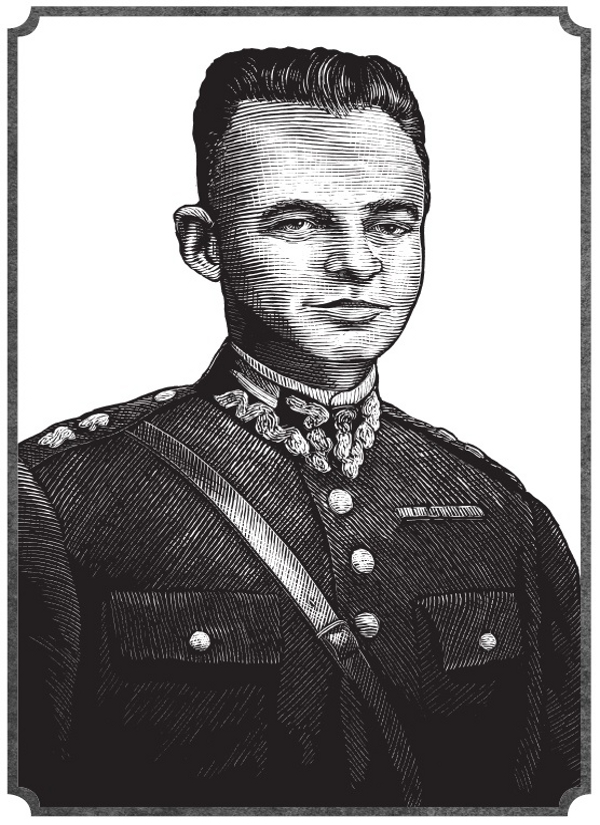

Let me introduce you to a hero you have probably never heard of. I think he may be one of the greatest men who ever lived.

His name was Witold (Vee-told) Pilecki. He was born on May 13, 1901, in Russia. These words would have made him wince. His family had been forcibly removed to Russia from their beloved Poland as punishment for a Polish uprising in the 1860s. There were no Polish patriots more passionate than the Pilecki family.

Witold exemplified the Polish soul. He played guitar, painted, wrote poetry, composed songs, gave himself fully to his Catholic faith, and dreamed of a free Polish homeland. He was also fiercely courageous. While still a teenager, he secretly joined a Polish equivalent of the Boy Scouts, though it had been outlawed by Soviet Russia. He fought in guerrilla units during the Soviet-Polish war that followed the First World War and took his examinations to graduate from high school only after that conflict ended. He attended college and then officer training classes, which allowed him to be commissioned as a lieutenant in the Polish army in 1926.

Life moved quickly for him thereafter. He married, had two children, inherited his family’s small estate in Belarus, and helped develop paramilitary units in his home region. He was so effective he was awarded the Silver Cross of Merit in 1938. World War II began the next year.

The invading Germans defeated his 19th Infantry Division on the sixth of September. He fought on with various guerrilla units long after the Polish government had given the country up and taken exile in Paris. Witold stayed in his homeland and helped organize an underground resistance movement—the Tajna Armia Polska, or TAP—the Polish Secret Army. The TAP was built on Christian principles, had no political party affiliation, and grew to as many as twelve thousand men.

Not long after, intelligence reached the TAP that people were being gassed at a prison camp in Auschwitz. Assuming the Allies would liberate the prison camp immediately, Witold and his colleagues began making plans to help. To their dismay, they soon realized the Allies had no such plans. In fact, the TAP wasn’t sure the Allies even knew of the camp’s existence.

The TAP began preparing to liberate Auschwitz themselves. This is when Witold inscribed his name in the world’s Hall of Heroes.

On September 19, 1940, Witold Pilecki tucked forged identity papers into his jacket, kissed his wife and two children good-bye, and intentionally walked into a Nazi roadblock. He was on a mission—a mission to get himself sent to Auschwitz. Once imprisoned, he intended to get intelligence out of the camp to the Polish resistance movement, organize an internal uprising, and boost the morale of Polish inmates.

I want to say it again. Witold Pilecki voluntarily got himself arrested and sent to Auschwitz, the worst of the Nazi extermination camps.

The sketchy journals he was able to smuggle out give some indication of the horrors he endured. They are filled with Nazi butchery, tales of crematoriums, pseudo-medical experiments, and the Nazi delight in killing Poles.

Witold was imprisoned in Auschwitz for 947 days—more than two and a half years—days filled with starvation, beatings, and torture. Yet they were also days of success, for he fulfilled every assignment the Polish Underground gave him. Then he escaped. Had he sat out the rest of the war, no one would have thought less of him. Instead, he joined a British unit and continued to fight Nazis. He was captured in an uprising near Warsaw and held in a prisoner of war camp until the end of the war.

While much of the world celebrated the close of World War II, patriotic Poles quickly realized they had fought Nazi oppression only to end up under equally evil Soviet rule. Witold, ever the patriot, threw himself into this new fight. He again joined an underground movement, taking dangerous assignments to gather intelligence on Soviet operations. He was eventually captured by communist Poles who were in league with the Soviet Union. He was interrogated endlessly, tortured to the threshold of death, and finally found guilty in a farce of a trial in which he received three death sentences.

Just before his execution, he wrote a poem that includes the line, “For though I should lose my life, I prefer it so, than to live, and bear a wound in my heart.” This “wound” was knowledge that anyone else should suffer for his spying. He was executed on May 25, 1948, at Warsaw’s Mokotow Prison. The details of Pilecki’s bravery could not truly emerge until after the collapse of Communism in 1989. He posthumously received the Order of Polonia Restituta in 1995 and the Order of the White Eagle, the highest Polish decoration, in 2006.

His legacy is captured in the words he often gave as his personal credo: Bóg, Honor, Ojczyzna—“God, Honor, Country.”

He had lived his life for his people and had given everything again and again. He is one of the greatest heroes of Poland, but he is also one of the greatest examples of self-sacrifice we can know. To choose Auschwitz with all its hellish tortures and death required an almost complete surrender of personal preference, inwardly cutting ties with everything dear in this life. This is the essence of being both a man and a patriot. Witold Pilecki is an enduring symbol of both.

We will likely never be asked to have ourselves imprisoned. Most of us will never join a guerrilla movement during a war. We may never be asked to risk our lives.

Simply through the mandate of being men, though, we are asked to surrender our rights and comforts for a higher cause—the responsibility for all we are given as men. Our rights come after the requirements of God, of course, but they also come after whatever is required to serve our wives, to invest in the lives of our children, to stand for righteousness in our communities, or to tend anything else that is within the field assigned to us.

Being a man is a privilege, not an entitlement. It is a surrender of our priority. It is a laying down of our lives, not physically but inwardly—our preferences, our pleasures, sometimes even our dreams. Our version of Witold Pilecki’s medals comes in the lives we offer to God, lives we have bled and sweated and prayed and given ourselves for.

This is what it means to be a man.