APPEARANCE

The Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) is a small gull with a wingspan of about 85 cm. It is common both on coasts and inland, and while it is less abundant than the Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), it is much more familiar to the public thanks to its dark head in summer (Fig. 15, left), which gives rise to its common name. The hood is actually dark brown, not black, and while the eye is also dark, the white semicircle around the back of it draws attention to it when the bird is seen at close range. The species is frequently attracted to food in towns and even large cities, both inland and on the coast, but for more than half of the year adults lack the dark hood and are more difficult to identify. At that time, the white head has only small, dark grey patches behind the eyes, but the red bill and legs, and the light leading edge to the wing when in flight, aid recognition (Fig. 15, right). The sexes are similar, with the male being only slightly larger than the female.

FIG 15. Adult Black-headed Gull in summer plumage (left) and winter plumage (right). (Left, Alan Dean, right, Nicholas Aebischer)

Juveniles differ markedly from the adults. They have brown feathers on the wings, on the back of the neck and on top of the head, and these form part of a cryptic patterning that helps to conceal them in vegetation before they fledge. During the first year of life, they lack the bright red legs and bill of the adults, and, although present, the white outer edges to the wings are less obvious. First-years have a black band to the tail, but as this is also present in several other species of small gulls in their first year of life, it is a useful characteristic to age but not to species identification. In the first summer after hatching, the immature birds develop a dark hood later than the adults; this is usually incomplete and mixed with some white feathers. They also retain most of the dark band to the tail. Following the autumn moult, immature individuals entering their second year of life assume the adult plumage, including an all-white tail, but many still have less intensely red legs at this stage.

DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS

The Black-headed Gull is widely distributed in Europe and breeds across Asia, and there is no evidence of subspecies within this large range. The species extended its western range in the twentieth century, reaching the Faeroes early on at an unrecorded date, Iceland in 1910 (50,000 adults now breed there) and Greenland in 1969. Breeding in North America was suspected as early as 1963 but not proven until 1977, when nesting by 14 pairs was recorded in Newfoundland. More recently, breeding has been suspected at other sites in North America, with recently fledged young being reported at several locations from Labrador to Massachusetts. Several young birds ringed in Iceland have been recovered during winter in Newfoundland and Labrador, but only one ringed individual of this species is known to have crossed from the mainland of Europe to the New World. It was ringed in the Netherlands and recovered 200 km off the coast of Labrador, so it seems likely that those seen in North America are mainly individuals reared in Greenland and Iceland.

Movement to North America has progressed in a series of stages rather by a sudden irruptive transatlantic movement from Europe, with birds breeding or reared in the Faeroes, Iceland and Greenland gradually moving west. This spread, together with a northern movement in Norway, Sweden and Finland, has been interpreted as a response to climate change. However, this theory ignores the spread of breeding to Italy (1960) and Spain (1960), and the fact that the increase within the species’ core area in Europe during the twentieth century has probably been mainly responsible for the spread of the western limits of its breeding distribution.

Today, unknown numbers of Black-headed Gulls nest across Asia and some 4 million to 5 million adults breed in Europe, of which about 250,000 nest in Britain and Ireland. Those breeding here probably represent less than 5 per cent percent of the world population.

The Black-headed Gull is the commonest gull frequenting sports fields, landfill sites, harbours and areas around large shopping complexes, and the birds also seek food in urban streets, domestic gardens and even at bird tables during severe winter weather. In many areas, they are also the gull most likely to be seen following the plough in agricultural fields. The species achieved fame in literature as the character Kehaar in the well-known book Watership Down, written by Richard Adams (1972). Kehaar suffered a damaged wing and took refuge at Watership Down, eventually recovering and returning to his colony.

Numbers of Black-headed Gulls in and around towns and cities can be high, particularly in winter, but this has not always been the case. For example, until the end of the nineteenth century the species was considered scarce in central London, but the birds are now present here in their thousands in winter, where they are abundant in parks, sports fields, lakes and the river Thames, often seen competing vigorously for scraps of food.

The gathering of flocks of Black-headed Gulls around towns and cities varies through the year. Fig. 16 shows their density month by month within a radius of 5 km of Durham, where many were recorded on sports fields, pastures and the river Wear running through the city centre, or patrolling streets and shopping centres in search of discarded food. The gulls retreated to their colonies in March, and since none of these was within 40 km of the city, only an occasional immature bird was recorded in April and none of any age in May and June. There are many accounts of Black-headed Gulls frequenting other areas in winter and being absent there in spring and summer. It is obvious that the distribution of the birds in Britain becomes much more clumped during the breeding season and is limited by feeding range from colonies. At most colonies, first-year (non-breeding) Black-headed Gulls are also infrequent and those that are encountered are seen feeding with adults well away from colonies, commonly on intertidal estuaries.

FIG 16. The seasonal variation in the numbers of Black-headed Gulls within a radius of 5 km of the city of Durham between 1982 and 1984, and in the absence of local breeding colonies. In each year, the gulls were absent in May and June, and the first individuals arrived in July, coinciding with the Durham Miners’ Gala, when a considerable amount of food was dropped by the large numbers of people attending the event. Based on data collected by MacKinnon (1986).

HISTORICAL BREEDING STATUS IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND

The status of the Black-headed Gull in Britain and Ireland in or before the twentieth century is not clear owing to a lack of detailed information. On its website, the British Trust for Ornithology (www.bto.org) says that the species was a rare breeding bird in Britain in the nineteenth century, and the statement made by John Gurney Jr in 1919 that the species was in danger of extinction here cannot be true. Both opinions lack supporting evidence and are contradicted by the extensive egg collecting that occurred at that time (here), and by the historical evidence accumulated by Michael Shrubb in his book Feasting, Fowling and Feathers – a History of the Exploitation of Wild Birds (2013). It is likely that the movement of colonies was misinterpreted as a decline in numbers, and that the ‘disappearances’ of the birds were probably movements of adults elsewhere and the establishment of new colonies in response to nest predation. Such movements of colonies are also frequent, and better known, in the Little Tern (Sternula albifrons), where they are closely related to poor breeding success induced by predators or by human disturbance.

There can be little doubt that the numbers of Black-headed Gulls breeding in Britain increased in the period between 1900 and 1973, as did those of many other gull species breeding here. However, Black-headed Gulls are not easy to count accurately. Colonies of very varying sizes occur both on coasts and inland, and the latter are often particularly difficult to count, with nesting taking place in marshes, on islands in lakes and tarns, and sometimes among tall or floating vegetation in boggy areas. In addition, colonies on moorland are often small and scattered, and new ones can remain overlooked for some time.

The first census of Black-headed Gulls in England and Wales was made in 1938, with further surveys in 1958 and 1973. The report of the census made in 1973 concluded that there were between 200,000 and 220,000 breeding adults, and that since 1938 there had been an increase of 177 per cent, while the number of colonies containing more than 2,000 adults had doubled since 1958. However, part of the reported increase might be attributed to a better coverage of colonies in 1973. In Scotland, a census made in 1958 suggested that there had been little recent change in abundance, but that numbers had continued to be influenced by uncontrolled egg collecting. The national censuses of Britain and Ireland in 1970 and 1985 counted only coastal-nesting Black-headed Gulls and did not consider the appreciable numbers nesting inland. The census in 2000 included inland colonies for the first time and resulted in an estimate of about 336,000 breeding adults in Britain and Ireland, of which 44 per cent were nesting inland.

FIG 17. Map of the breeding distribution of the Black-headed Gull in Britain and Ireland in 2008–11. Reproduced from Bird Atlas 2007–11 (Balmer et al., 2013), which was a joint project between the British Trust for Ornithology, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. Channel Islands are displaced to the bottom left corner. Map reproduced with permission from the British Trust for Ornithology.

Between 1970 and 1985, a 71 per cent decline in coastal-breeding Black-headed Gulls in the Republic of Ireland was reported, but the numbers there had recovered by the time of the 2000 census. It is possible that an appreciable proportion of the missing birds in 1985 had not, in fact, died, but had moved to new breeding sites not visited at that time.

The general impression from these censuses is that the numbers of breeding Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland increased during most of the twentieth century, and then numbers showed little overall change in Britain between 1985 and 2000. The meagre and incomplete data available since then hints that numbers have been maintained.

The BTO Bird Atlas 2007–11 data, collected between 1968–72 and 2007–11, reported a reduction of 55 per cent in the number of 10 km squares in Britain and Ireland containing breeding Black-headed Gulls. Whether this reflects a decline in overall numbers is uncertain, as it could be the result of a trend towards fewer, larger colonies. Sample counts made at some coastal sites by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) show little evidence of a national change in numbers between 1986 and 2015, and this is supported by the national censuses in 1985 and 2000, which (although the earlier census was incomplete) did not suggest any major overall numerical changes within Britain and Ireland.

There has been a trend over time towards decreasing numbers of Black-headed Gulls breeding at inland sites, while numbers nesting at coastal sites have increased in England and Wales. However, this change does not seem to have occurred in Scotland. This movement probably reflects that birds breeding on coastal islands are often better protected from both humans and Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) than those breeding inland. The impact of the dramatic increase of Fox numbers in Britain in recent years is not frequently appreciated. Stephen Tapper (1992) found that numbers of this predator had increased fourfold between 1961 and 1990, and suggested that the effect of Fox predation on Black-headed Gull colonies may be greater and more widespread than that caused by American Mink (Neovison vison).

COLONIES

Colony sizes

The Black-headed Gull is a colonial breeder, nesting on a wide range of sites, including lakes, reservoirs, small moorland pools and tarns, marshes, sewage farms, clay pits, dunes, saltmarshes and industrial ponds. While numbers of nests in some colonies are easily counted, others are difficult to measure as the nests can be concealed by vegetation or lie on boggy ground, making access difficult or risking damage to the vegetation. Good vantage points do not exist near many colonies, and different methods are therefore needed here to estimate their size.

The basic unit used to measure the size of a colony is the number of nests, applying the realistic assumption that two adult birds are associated with each nest. In very large colonies, sampling of nest density has been used and then extrapolated across the total area of the colony as delineated from aerial photographs or detailed large-scale maps. At some sites, pair and hence nest numbers have been estimated through the less reliable method of counting numbers of birds in the air when disturbed and then using a conversion factor, such as dividing by 1.55. Most Black-headed Gull census counts have errors, which should be considered when making interpretations of the national status of the species and possible changes in abundance over time.

FIG 18. Part of the colony of Black-headed Gulls nesting with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis) on Coquet Island, Northumberland. (John Coulson)

Data for years since 1980 on Black-headed Gull colony size recorded in the UK Seabird Colony Register allows for an in-depth assessment. While the species is essentially a colonial breeder, solitary breeding pairs on the day of counting comprised 10 per cent of the sites in Scotland and 8 per cent in England. Whether many of these pairs had been solitary for the entire breeding season is uncertain, because most of the nesting sites were visited by counters only once. It is possible that some single pairs were the sole remainders of a group present earlier in the breeding season that had suffered predation or disturbance, and had deserted the site prior to the observer’s visit. Single pairs of Black-headed Gulls can probably breed without the need of stimulus of other pairs, although when they do so, they nest late and their breeding success is usually low.

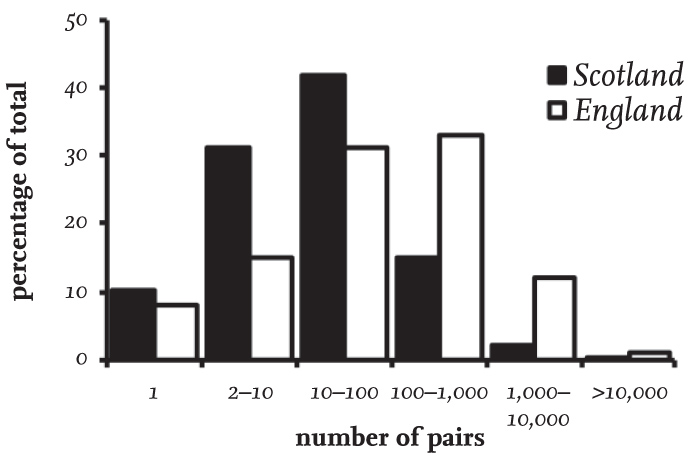

In Britain and Ireland, the numbers of pairs of Black-headed Gulls estimated at breeding sites (subsequently referred to as colonies for convenience, and including sites with single pairs) between 1980 and 2015 ranged from only one pair to more than 10,000 pairs. Overall, a third of colonies in Britain contained between 10 and 100 nesting pairs (Fig. 19).

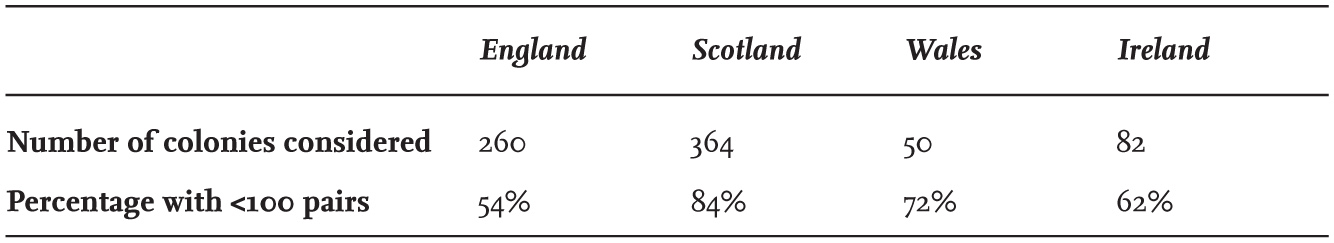

At the same time, the average size of colonies differed between Scotland and England, with 84 per cent in Scotland having fewer than 100 pairs (Table 8), while the comparable figure for England was a third lower, at 54 per cent. Colonies with 100 to 1,000 pairs were twice as frequent in England than in Scotland, while colonies of more than 1,000 pairs formed 13 per cent of all sites recorded in England, but only 2 per cent of those in Scotland.

These differences reflect the type of nesting sites used in the two regions, with the majority in Scotland being inland on upland sites and usually associated with relatively small waterbodies, while in England large coastal colonies were more frequent and were sometimes extremely large. The distributions of colony sizes in Wales and Ireland were intermediate between those in England and Scotland, with 72 per cent of colonies in Wales and 62 per cent in Ireland having fewer than 100 pairs (Table 8).

FIG 19. The size distribution of Black-headed Gull colonies (including sites with only one pair) in England and Scotland between 1980 and 2015, based on Seabird Colony Register data for 364 colonies surveyed in Scotland and 260 in England.

TABLE 8. The proportion of Black-headed Gull colonies in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland with fewer than 100 breeding pairs, based on data from 1980–2015. Sites with a single pair present have been included.

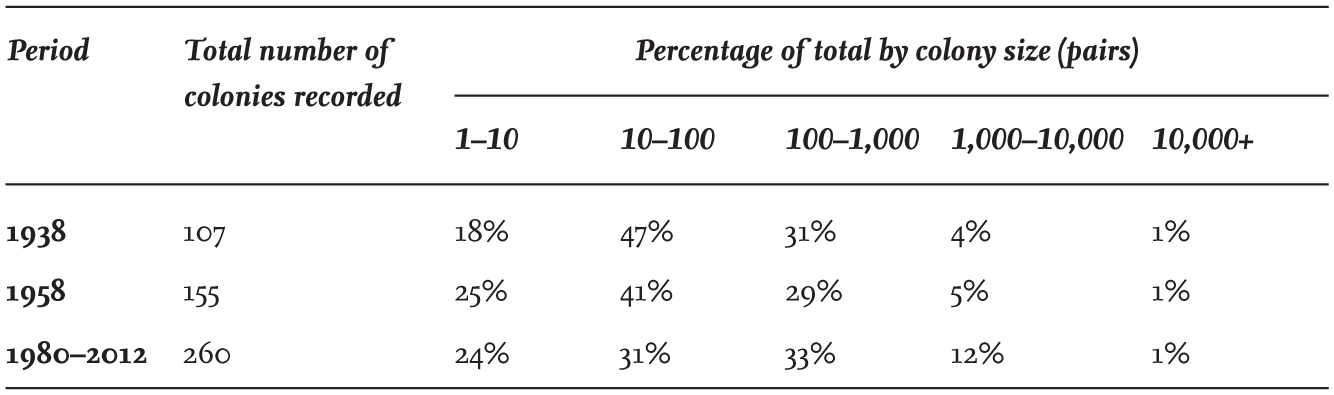

TABLE 9. The percentage of Black-headed Gull colonies of different sizes in England and Wales in 1938, 1958 and 1980–2012. Sites with only one pair are included.

A comparison between the size of colonies reported in the 1938 and 1958 censuses made in England and Wales, and more recent data collated in the Seabird Colony Register, show progressive changes in colony sizes over time (Table 9). There has been an overall decrease in the proportion of colonies with fewer than 100 pairs since 1958, while the proportion and total numbers of large colonies with more than 1,000 pairs has more than doubled over the same period. Many colonies – particularly small ones in England and Wales – have disappeared for various reasons, including disturbance, predation and drainage, while others – particularly large ones – are now protected within nature reserves, although even a few of these have disappeared.

Persistence of colonies

While some Black-headed Gull colonies persist for many years, in general they are not as permanent as those of the Kittiwake or Herring Gull (Larus argentatus). Over the past hundred years, many Black-headed Gull colonies have disappeared while new ones have become established. Small colonies are particularly susceptible to decline, and this is especially true of those on upland moors, where the birds nest around small bog pools, reservoirs and lakes. A consequence of this is that some of these mobile groups can be missed during census work.

Various reasons have been suggested for the desertion of colonies. In some cases these are speculative, and include drainage, military activity, competition from increasing numbers of large gulls, aggression by Mute Swans (Cygnus olor) and Canada Geese (Branta canadensis), egg collecting, keepering, and predation by Foxes and American Mink. Rats and Foxes have been a persistent problem for Black-headed Gulls nesting at Blakeney Point in Norfolk, and no young were reared at the colony in 2000. In 2014, Fox predation at the same site resulted in very few chicks being reared by the 2,200 pairs present, while in 2016 an appreciable increase of rats caused the gulls to abandon the colony and, presumably, move elsewhere.

Ravenglass colony

The site of the very large Black-headed Gull colony on the coast of Cumbria at Ravenglass is owned by the Muncaster Estate. There has been continuous collection of eggs there since the seventeenth century, a practice that was recorded as being extensive in 1886. Del Hoyt has suggested the colony had an annual yield of 30,000 eggs over many years. Neither Michael Shrubb’s searches (2013) nor my own have uncovered documentation to confirm or contradict this statement, but the colony was certainly used consistently as a source of freshly laid eggs for much of the twentieth century by the estate, and workers also took some young from time to time. The collection of eggs was well organised and was stopped each year on an agreed date, which left time for successful breeding by birds laying late or with repeated clutches. David Bannerman recorded that the estate collected 72,398 eggs at Ravenglass in 1941 and 24,568 in 1951, when a further 6,000 eggs were taken (presumably illegally) by others.

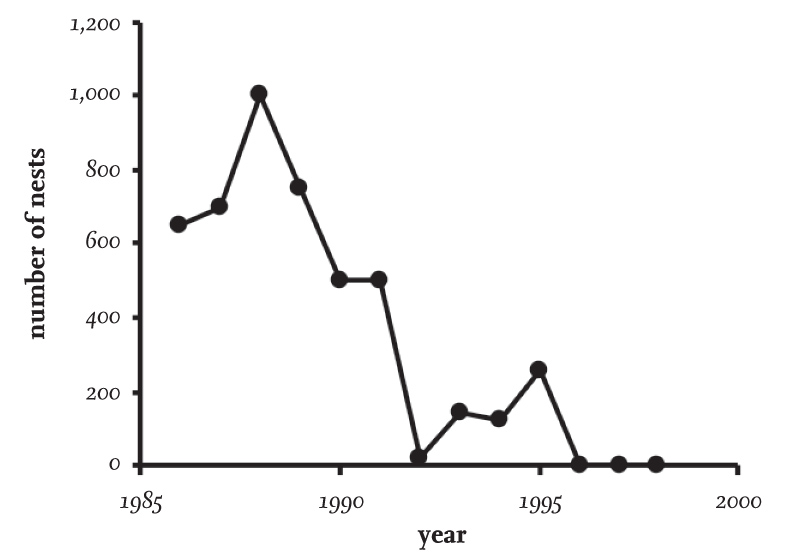

In 1954, the site was leased to Cumberland County Council as a local nature reserve and egg collecting ceased. The gulls were protected and studied in the ensuing decade by Niko Tinbergen’s research group from Oxford University. During the period 1954–68, the colony size remained between 8,000 and 12,000 pairs, but during this time predation on eggs, chicks and adults occurred from time to time and breeding success was low. In 1968, a full-time warden was appointed, and he reported that 8,100 pairs nested. From then onwards, a marked decline continued each year; Neil Anderson’s study in 1984 found only 1,300 pairs nesting, and the colony was totally deserted in 1985 (Anderson, 1990). Five pairs nested there in 1988 and three pairs in 1989, but none since (Fig. 20). Predation by mammals over several years, particularly Foxes, was thought to be the cause of decline and ultimate desertion. The abandonment of the Ravenglass colony probably involved a movement of Black-headed Gulls to several other colonies, possibly those in the Ribble Estuary and Sunbiggin Tarn, because no new or established colonies were nearer.

FIG 20. The numbers of nests (pairs) of Black-headed Gulls nesting at Ravenglass in 1939–90.

The history of the Ravenglass colony and other similar sites illustrates two important points. First, egg collecting over many years that was well organised and had an early cut-off had no adverse effects on the colony and did not lead to its desertion. Second, the creation of a nature reserve without effective predator management does not prevent colony desertion; indeed, in recent years there have been other instances of colonies within nature reserves disappearing.

Sunbiggin Tarn colony

The history of the large inland Black-headed Gull colony at Sunbiggin Tarn, near Orton in Cumbria, parallels that of Ravenglass. In 1891, a thousand eggs were said to have been collected from the edge of the colony. The site was estimated to contain 400 pairs in 1938, 1,200 pairs in 1958 and 2,500–3,000 pairs in 1973. The colony continued to grow and reached about 12,500 pairs in 1988 (see below), maintaining similar numbers in 1989, when Foxes were seen. Numbers of gulls then showed a noticeable decline in 1990, and only a few pairs bred in 1991. The colony persisted with a few pairs, and by 2000 had increased to 1,200 pairs, but by 2010 gulls had ceased nesting at the site altogether (Fig. 21).

Direct counting of all nests proved to be impossible at the large Sunbiggin Tarn colony because of the boggy areas within the tarn and the high vegetation, which would be damaged by trampling during a search for nests. A count of the colony was not obtained for the national census in 1985–87, and in 1988 a novel method was used to measure its size. This involved capturing a large sample of the breeding adults in late May and dyeing their tails yellow. A total of 1,010 adults were captured and marked during two weeks by attracting them with food placed about 1–2 km from the colony and then cannon netting them. When marking was completed, the proportion of dyed birds in the colony was obtained by counts of 4,540 adults passing in and out of the site along flight lines. Of these, 186 – or one in 24.4 – had yellow tails, so multiplying the total number dyed by this proportion (24.4) gave a measure of the total number of breeding birds in the colony. This produced an estimate of 24,644 adults (rounded off to 12,500 pairs), identifying it as the largest inland colony in Britain at the time. Unfortunately, Clare Lloyd et al. (1991), in their book reporting the status of seabirds in Britain and Ireland in 1985–88, erroneously recorded this census as 25,000 pairs of Black-headed Gull, not 25,000 individuals.

FIG 21. Part of the large Black-headed Gull colony at Sunbiggin Tarn, Cumbria, during an exceptionally dry spring in 1984. (John Coulson)

Part of the colony at Sunbiggin Tarn could be viewed by people from the nearby road, and they often fed the gulls, which made attracting and capturing the birds in cannon nets much easier. The public’s interest in the well-being and size of this colony was considerable, and not without humour. The investigators netting adult birds had to explain to onlookers what they were doing and that there would be an explosion when the cannons were discharged. On two occasions, the observers remarked that they were puzzled because they could not find a gull in their field guides with a yellow tail, and asked whether this was a rare species! Members of the public often also liked to guess how many gulls were nesting, generally coming up with figures that were widely lower than the actual numbers calculated – most likely because the extent of the colony could not be viewed from a single vantage point. Incidental to the main study, adults with yellow tails were seen feeding in the Lake District and several places on the river Eden up to 40 km from the colony a few days after marking.

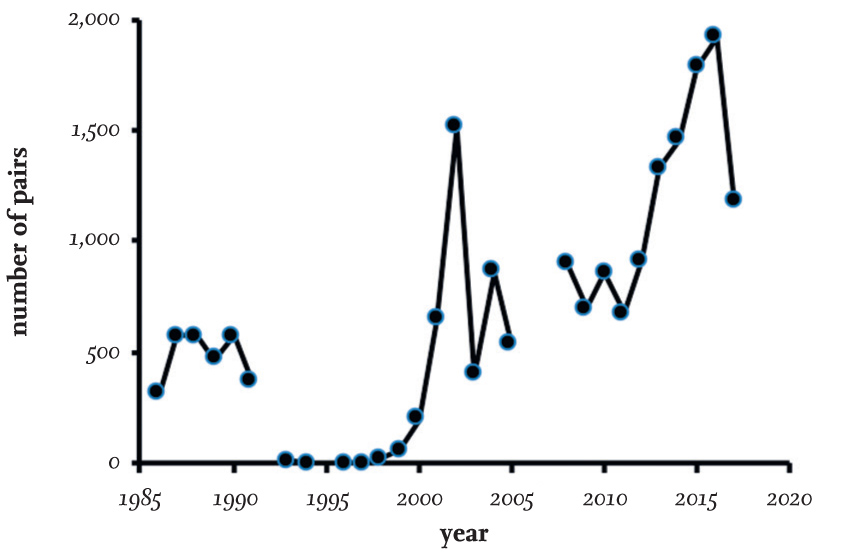

FIG 22. Numbers of Black-headed Gulls nesting on the Sands of Forvie, 1986–2017. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

Ythan Estuary (Sands of Forvie) colony

Black-headed Gulls have nested at the Sands of Forvie at the mouth of the river Ythan, near Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, for many years. In the late 1980s, about 500 pairs nested there annually, along with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) and Eiders (Somateria mollissima). Fox predation became intense in about 1990, when breeding Sandwich Terns and Black-headed Gulls abandoned the area and the number of young Eiders declined. In 1994, steps were taken to reduce and then exclude Foxes from the breeding areas, and in 1998 the first Black-headed Gulls returned to breed. Numbers increased rapidly in the following years and reached more than 1,500 pairs in 2002. This level was not maintained, but numbers exceeded 500 pairs each year up to 2012, when the colony size increased annually until 1,921 pairs were recorded 2016 (Fig. 22).

Foulney and other colonies

The colony at Foulney in north-west England (Fig. 23) showed a pattern of decline spread over a few years in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before breeding there ceased altogether sometime in or before 1996. As elsewhere, predation of eggs and nestlings was considered the main cause.

FIG 23. The decline and subsequent total desertion of the Black-headed Gull colony at Foulney, a coastal site in Cumbria. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

FIG 24. The rapid build-up of a Black-headed Gull colony at the RSPB reserve at Saltholme, near Stockton-on-Tees, between 2005 and 2017. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

There are many other examples of Black-headed Gull colonies that showed appreciably smaller numbers each year before breeding stopped entirely. The national census in 2000 listed 12 large colonies that had disappeared since 1985, plus a further five that had lost more than 89 per cent of the maximum numbers of breeding pairs over recent years. In contrast, nine colonies showed major increases within a short time period, including the colony at Langstone Harbour in Hampshire, which in the 15 years between 1985 and 2000 increased more than 60-fold. Many new colonies had become established and subsequently grew rapidly, such as those at Hamford Water in Essex, Coquet Island in Northumberland, Larne Lough in Northern Ireland, Loch Leven in Scotland, the Ribble Estuary in Lancashire and Saltholme (Fig. 24), a nature reserve near Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham, that has been managed by the RSPB since 2007.

Reasons for colony declines

Egg collecting, particularly if stopped early in the season, has carried on year after year at several Black-headed Gull colonies without resulting in abandonment. And at Ravenglass, Neil Anderson’s investigations (see above) ruled out a possible link between the decline there and contamination associated with the nearby Sellafield nuclear fuel reprocessing and decommissioning plant. In many areas – particularly the fenland of eastern England – colonies have been lost due to drainage and expanding agriculture, which have removed otherwise suitable nesting sites. However, it seems that the main cause of decline and disappearance of Black-headed Gull colonies is predation of eggs, young and sometimes adults. The presence and increase in numbers of mammalian predators, particularly Foxes and American Mink, have been associated with the decline of the colonies at Sunbiggin Tarn, Ravenglass and the Sands of Forvie. During his studies at Ravenglass, Hans Kruuk found that four Foxes killed 230 Black-headed Gulls in one night, and a total of 1,449 adult gulls were killed by Foxes in two consecutive breeding seasons. Studies made at the colony by Ian Patterson during the period of appreciable mammalian predation activity found that scattered and outlying pairs of gulls were entirely unsuccessful, while those in the central core areas, although having a very low success rate, did succeed in rearing a few young (Patterson, 1965).

Once colonies have started to decline, the impact and pressure from the same numbers of Foxes or American Mink produce a vicious spiral that has an increasing impact on the remaining birds. Another predator at Ravenglass was the Hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), which had developed the habit of consuming the flesh of live gull chicks that had not reached fledging age. Several of the colonies referred to in the past as sites where eggs were collected have now ceased to exist, and some authors have attributed these to uncontrolled egg collecting extending throughout the entire breeding season. It is ironic, therefore, that it was only after egg collecting had stopped at Ravenglass that the colony declined and then disappeared, presumably owing to the lack of efficient predator control.

When a colony disappears in a matter of a few years, it is unlikely that the adults have died, but rather that they have moved to other sites and colonies. The decline at Sunbiggin Tarn following predation resulted in some adults moving to Killington Reservoir alongside the M6 motorway in Lancashire, a move confirmed by a few ringing recoveries of adults previously marked at Sunbiggin Tarn. However, this colony contains nowhere near the numbers of birds recorded breeding at Sunbiggin Tarn, which implies that many adults from Sunbiggin probably moved considerable distances and to several different sites, as no other single large colony was established within 80 km of it at the time of its decline. This is also true of many small, ephemeral colonies on upland moorland in northern England and Scotland. A consequence of this is that mobile groups of Black-headed Gulls are often overlooked, and new colonies can grow rapidly through immigration in only a few years – as has happened at Saltholme (Fig. 24).

Exploitation of eggs and young

In the past, both the eggs and young of Black-headed Gulls were extensively exploited in Britain by humans. Michael Shrubb gives a detailed account of this in his 2013 book, Feasting, Fowling and Feathers, from which I have extracted some of the information given below.

Through the combination of Black-headed Gull numbers, their extensive inland breeding often close to human populations, and the relatively easy access to many nests compared to those of gull species that nest on coastal islands and sea cliffs, the eggs of this species have been exploited more extensively than those of other gulls in Britain and Ireland for the past 500 years and probably longer. In some places in the sixteenth century, nearly fledged young were collected by driving them into nets, and they were then housed and fed until required for human consumption. Some were purchased by the wealthy for 4–5d each, (equivalent to about £7 at today’s prices) or given as gifts, just as we now give flowers. Oxford college records at the time also list Black-headed Gull eggs being bought for a fraction of a penny each.

In the seventeenth century, one landowner is said to have made a profit of £60 in one year (equivalent to about £7,000 today) by collecting and selling gulls’ eggs. Exploitation of young birds probably decreased over time, but they continued to be sent to London markets nonetheless, and egg collecting became more frequent and extensive. Exploitation continued into the eighteenth century, and there are more records at this time of eggs being collected throughout England and Scotland. There are also records of gull colonies disappearing, the causes of which were attributed at the time to excessive egg collecting.

In the nineteenth century, egg collecting for human consumption throughout Britain and Ireland was extensive. In some areas it was organised by the landowners, but elsewhere it appears to have been uncontrolled. Well-established markets existed in London, and eggs collected in bulk in Norfolk and Hampshire were sent there for sale. That the Black-headed Gull was widely distributed as a breeding bird in southern England is evident from records of the large numbers of their eggs being collected and sold in the London markets. For example, in 1800 some 8,000–9,000 eggs were collected at Scoulton Mere in Norfolk, while in 1864 and later, 2,000 eggs a year were collected. From 1858, 700 eggs were taken each year at Hoveton in Norfolk, and in 1864 alone, 2,000 eggs were collected. According to The Spectator (17 April 1897), in 1834 at Stanford in Norfolk, a ‘tumbrel-load’ of eggs was collected in a day and sold for 3d a dozen.

It is probable that landowners enforced a degree of protection to the gull colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries owing to the value of the egg trade. In some cases, collecting was limited to taking eggs only from nests that held one or, occasionally, two eggs, to ensure that those collected had not been incubated, and at some but not all sites, collecting ceased on 15 June. As a result, clutches of three eggs were often left untouched, while cessation of collecting in June permitted some gulls to re-lay and breed successfully from late, repeat clutches.

An account of annual egg collecting in Ayrshire, Scotland, in the first 40 years of the twentieth century is given by Ruth Tittensor in a 2012 edition of Ayrshire Notes. The eggs were collected for local bakeries and domestic use, and even for egg fights between youths. Interestingly, the article includes a personal account of egg collecting by a person who later became a senior member of the Nature Conservancy! Elsewhere, the sale of eggs also continued into the twentieth century. In the 1930s, for example, more than 200,000 gull eggs were sold annually at Leadenhall Market in London. Egg collecting increased extensively during the two world wars, with large numbers collected to supplement rationing. An archived Pathé News ciné film shows several Land Girls based at Muncaster Estate during the Second World War collecting baskets of eggs at the large Ravenglass colony and boxing them up in crates ready for dispatch to London. Hugh Cott describes eggs being on sale in Cambridge in 1951 at 9d each. A London market for Black-headed Gull eggs existed for the whole of the twentieth century, with some being sold as ‘plovers’ eggs’.

Today, despite current bird protection Acts, systematic collecting of Black-headed Gulls’ eggs is still permitted in England by licence holders, although there is little general knowledge of the numbers of licences and eggs collected. The licences are issued annually by Natural England for collecting eggs for food consumption. As a result of a request for information, Natural England responded in 2016 by stating that ‘Licences are only issued where evidence of hereditary/ancestral/traditional family rights to collect eggs can be given’. The public body also stated that it seeks ‘to ensure that collection of eggs is sustainable in relation to numbers collected and colony size’. However, I still await a response as to how this is achieved and where the records are deposited, since they do not appear in the Seabird Colony Register or local county bird reports. An accurate census of a colony where many eggs are collected is often difficult to carry out because of the greater spread of laying and repeat clutches.

A freedom of information request granted by Natural England in 2016 revealed that it had issued licences recently for egg collection at six sites in England: the North Solent nature reserve in Hampshire; Lymington, Pylewell and Keyhaven marshes, also in Hampshire; Barden Moor in North Yorkshire; and the Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve in County Durham. Currently, up to 40,000 eggs are collected annually and sent to London. These details are not publicised and I found no information in the published literature. A further freedom of information request to Natural England revealed that in 2015 it issued 24 licences to collect Black-headed Gull eggs in England (22 in Hampshire, one in Yorkshire and one in County Durham). Table 10 shows that the numbers of eggs collected in Hampshire remained at about the same level over the period 2009–15. Those taken in North Yorkshire increased 17-fold between 2011 and 2012, and since then the numbers collected have continued to increase, with more than 32,000 eggs taken in 2015.

No mention of these annual egg collections appear in recent county ornithological reports, while Natural England made the surprising statement that information prior to 2008 ‘has not been retained’. This public body should not destroy historical information on colony sizes and the numbers of eggs collected, and such data should be archived. Natural England also refused to identify the colonies from which eggs were collected, or to whom licences were issued, thereby preventing further research on these activities. How this quango carries out the annual monitoring of the colonies – as it claims to do – remains unknown, and why this information is not deposited in the national Seabird Colony Register, which it supports, requires investigation. It is likely that eggs laid by Mediterranean Gulls (Larus melanocephalus) are being inadvertently taken at some of the colonies for which licences are issued.

TABLE 10. The number of egg-collecting licences issued and Black-headed Gull eggs collected in Hampshire, North Yorkshire and County Durham in 2009–15, as reported by Natural England. The public body stated that data for earlier years have not been retained.

Natural England has indicated that the licences place restrictions on the dates of collecting, these normally covering the period 1 April to 15 May each year. They also restrict the length of time collectors can spend in the colonies on each visit. Natural England revealed that the County Durham licences authorise collection of eggs from three large colonies of gulls, which therefore must be in Upper Teesdale, but the quango is not willing to disclose which colonies are involved.

Black-headed Gull eggs collected in England are currently sold by up-market London stores and find their way onto the menus of several prestigious restaurants. The eggs are normally served hard boiled or lightly boiled and seasoned with celery salt, and a serving containing three eggs may cost anything from £7.50 to £22. One restaurant in 2015 was offering omelettes made from three gulls’ eggs filled with lobster meat.

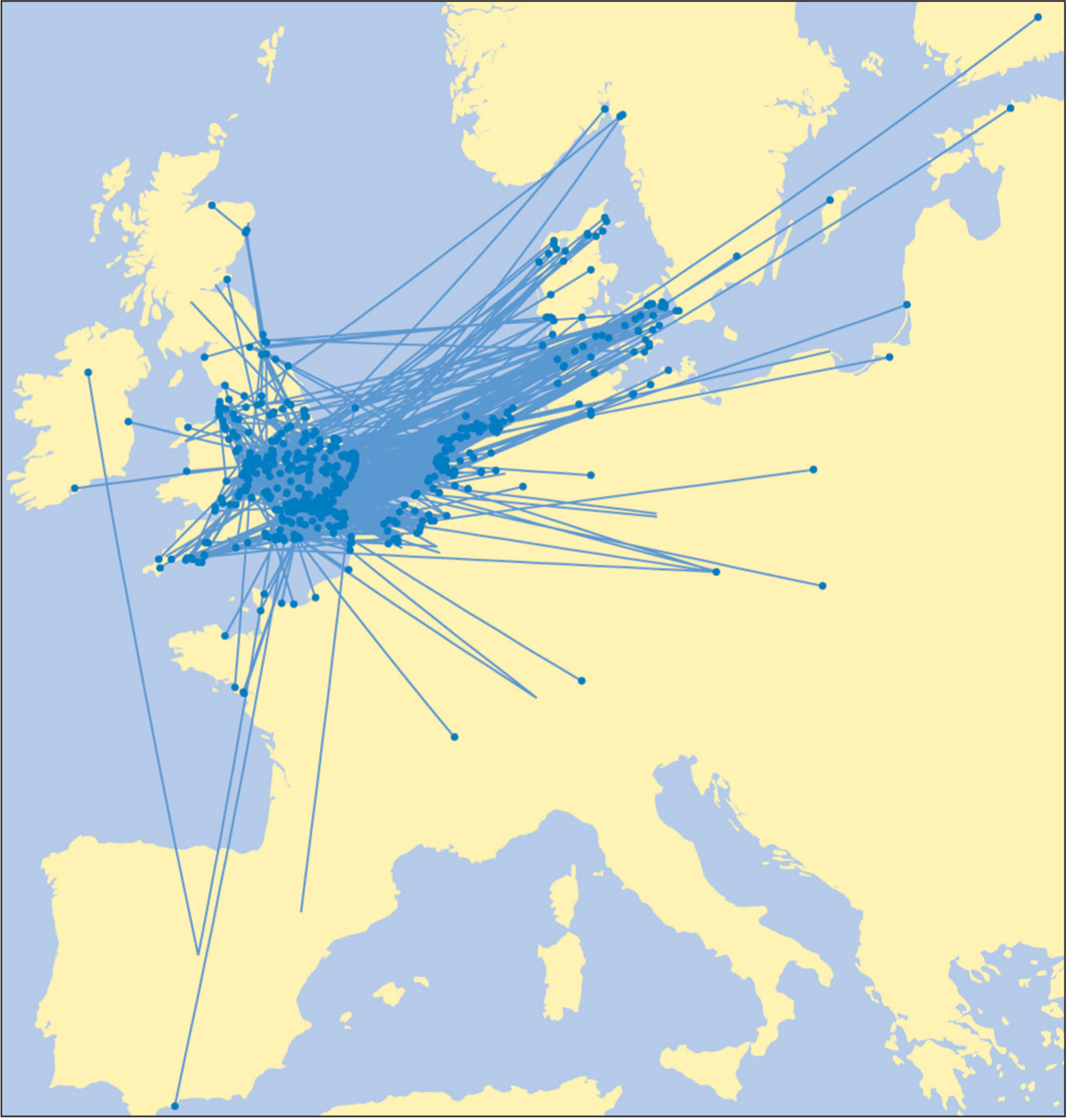

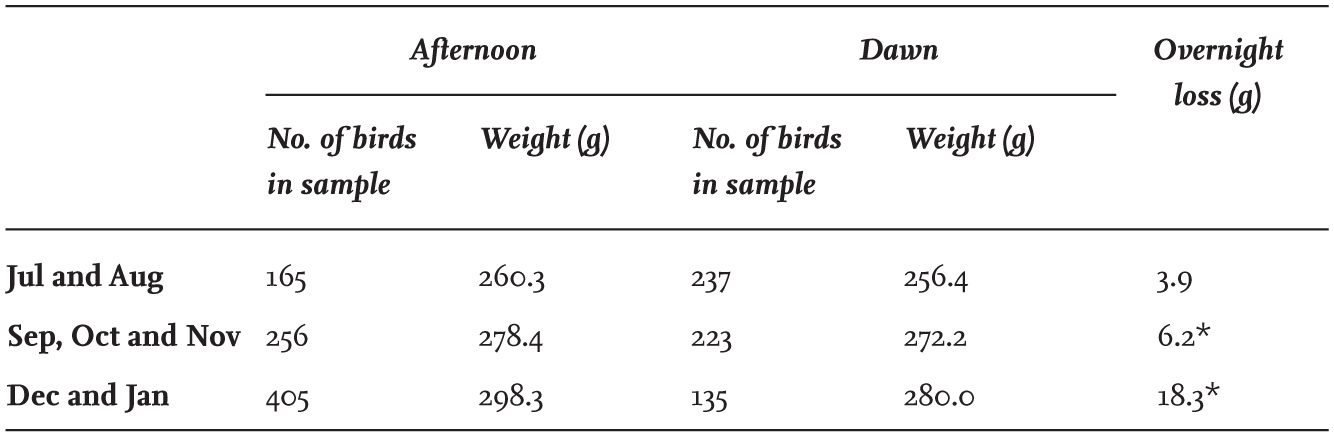

WINTER ABUNDANCE

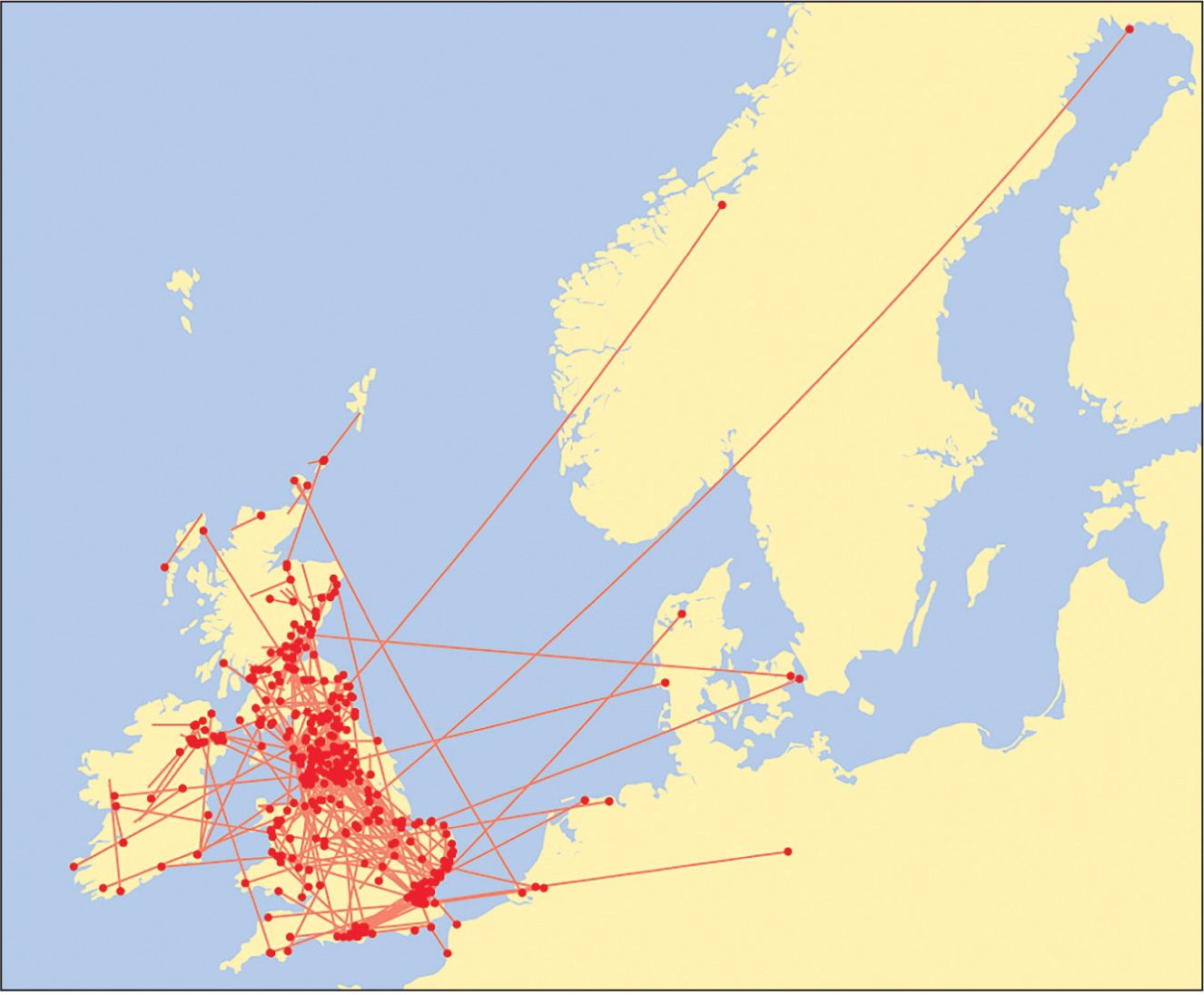

Few British-reared Black-headed Gulls leave the region in winter, with most making only local movements. Of those that do migrate, a higher proportion move to Iberia from south-east England than those reared in north-east Britain (Fig. 25). In contrast, large numbers of Black-headed Gulls move from the Continent to winter in Britain and Ireland.

FIG 25. Movements of Black-headed Gulls ringed as nestlings in south-east England and recovered outside the breeding season, based on 976 recoveries. Right: Similar mapping, but based on 447 recoveries of Black-headed Gulls ringed in north-east Britain. Note that fewer birds moved to Iberia from the north-east and that birds from the two regions have different winter distributions in Ireland. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

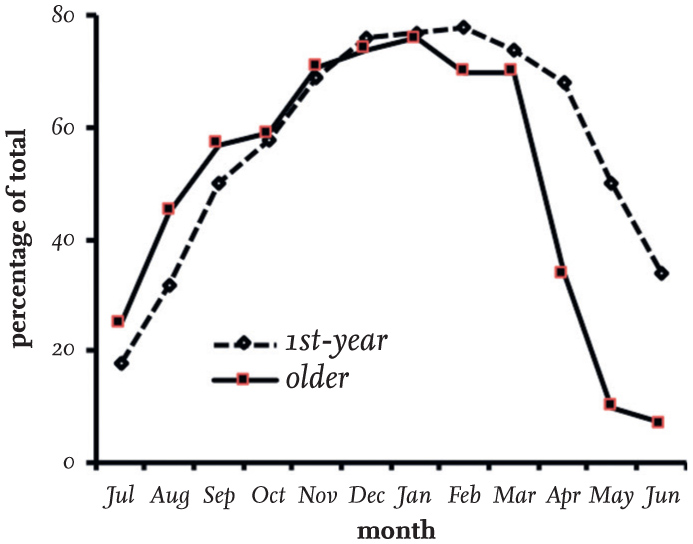

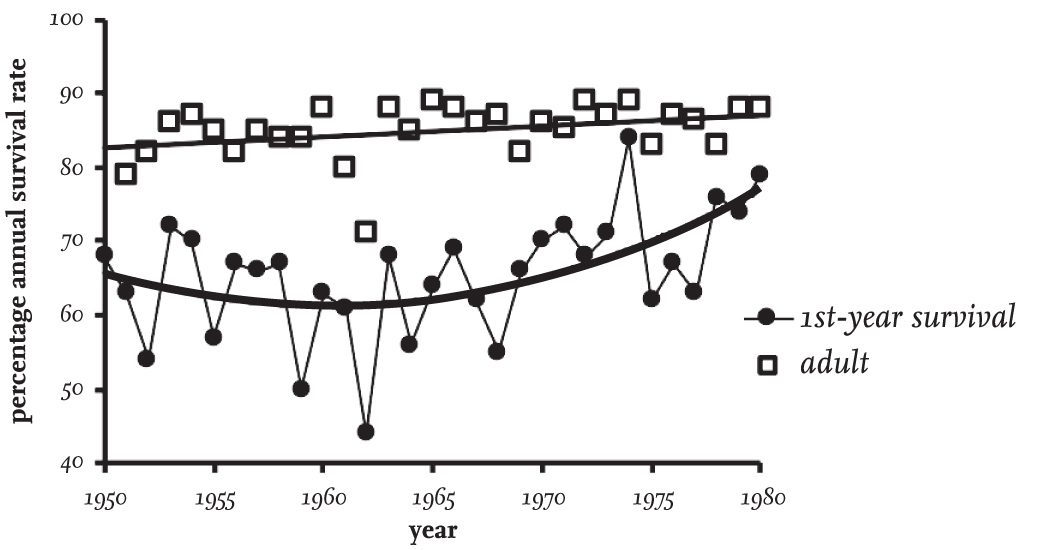

The BTO Winter Gull Roost Survey in 2004 estimated that more than 1.6 million Black-headed Gulls were using winter roosts in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland., and since the total did not include all winter roosts, there are probably more than 2 million individuals wintering here. This number can be compared with 280,000 breeding birds in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, which with immatures added comes to about 360,000 individuals. As most of these remain here in winter, it suggests that some 77–82 per cent of wintering Black-headed Gulls recorded in 2004 had moved here from the Continent. Gabriella Mackinnon and I obtained a comparable figure of 71 per cent, derived from ringing recoveries up to 1980 (Fig. 26). Both percentages are rough estimates, but it is clear that a major proportion of the wintering Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland originate from mainland Europe. Without new estimates, it is not known whether these numbers from the Continent have declined in more recent years as a result of the relatively mild winters.

Some readers may find it strange that, despite the satisfactory status and abundance of the Black-headed Gull as a breeding species in Britain, it has been Amber-listed here since 2015 as a species of conservation concern. This is based on the belief that numbers of wintering Black-headed Gulls in Britain have decreased by 33–50 per cent over the last 25 years, based on counts at winter night roosts. Since the British breeding numbers do not appear to have reduced (here), a possible explanation is that a major decline has occurred in northern Europe – the area from which many of the British wintering gulls originate. However, there is little evidence of this apart from Denmark. An alternative explanation for the decline in winter numbers in Britain is that more individuals are remaining on the European mainland during the milder winters encountered in recent years. A preliminary analysis of recent winter ringing recoveries of Black-headed Gulls marked on mainland Europe suggests that the change of wintering areas is more likely to be the explanation. If this is correct and the species is not declining appreciably in Europe as a whole, but is modifying its wintering areas, then is it really a matter of conservation concern? In contrast to the assessment in Britain, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) still regards the Black-headed Gull worldwide as a species of Least Concern.

FIG 26. The percentage of Black-headed Gull recoveries reported in Britain and Ireland in each month that were originally ringed in mainland Europe. Note the trend for first-year birds to return to the Continent later. The recoveries of a few Continental birds in May and June may represent rings reported some time after finding.

Arrival of wintering birds

The numbers of Black-headed Gulls arriving in Britain and Ireland for the winter boosts the breeding season population by a factor of about four. These visitors come from a wide range of countries in northern Europe, with most starting their journey at locations around the Baltic Sea (Figs 27 and 28). Their arrival is spread over several months, from late July to early November (see Fig. 26).

The countries of origin of Continental Black-headed Gulls visiting Britain varies slightly with their final destination, with birds flying south-west or west to reach their wintering area (Figs 27 and 28). The exceptions are individuals reared in Iceland, some of which winter in Scotland and Ireland, but most of which avoid England and Wales. Other Black-headed Gulls reared in Iceland have been recovered from the east coast of North America, a route apparently taken by all of those reared in Greenland, although this wintering area is totally avoided by birds breeding in mainland Europe and in Britain.

Fig. 29 shows the number of recoveries of foreign-ringed Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland for each month of the year up to 1985 in relation to those reported monthly from December to February, a period during which it is assumed that all individuals have arrived at their wintering areas. An appreciable proportion of foreign adults, possibly mainly failed breeders, arrive in Britain during July, but only a few young of the year have crossed the North Sea by the end of the month. A small proportion of first-year individuals reared abroad remain in Britain in the following summer, having failed to return to the Continent in the spring. These birds, entering their second year of life and already in Britain in July, are joined by more similar-aged immature birds moving here from the Continent.

FIG 27. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in north-east Britain (to the right of the thick black line) and recovered abroad in a subsequent breeding season. Note the five Iceland recoveries. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

FIG 28. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in south-east Britain (to the right of the thick black line) and recovered abroad in a subsequent breeding season. Note the single Iceland recovery. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

FIG 29. Recoveries in Britain and Ireland of Black-headed Gulls ringed in mainland Europe expressed as a percentage of the monthly recoveries between December and February. Note the high proportion of birds entering their second year of life (which moult early) reported in Britain in July, and the late departure of first-year birds in spring, with a few apparently remaining in Britain during the summer.

Numbers of all ages cross to Britain in August. By the end of that month, about half the adults that winter here have already arrived, but only 15 per cent of first-year birds have arrived. The early movement from countries bordering the Baltic Sea perhaps reflects the less favourable feeding conditions there. For example, the small tidal changes in the Baltic markedly restrict the extent of inter-tidal areas available for foraging, while the warmer and drier continental weather makes earthworms less available there in late summer.

There is evidence of a lag in new adult arrivals in Britain in September, probably because most adults are still completing their moult and growing their longest primaries. The lack of, or reduction of, these long feathers must impair their ability to make long flights. A second peak of arrival occurs in November, and by the end of that month most of the adults that winter here have arrived, apart from a few birds that possibly turn up in December. The maximum numbers of Black-headed Gulls are present in Britain for only three months, from December to late February.

The timing of immigration of first-year and adult Black-headed Gulls in autumn to Britain depends on the country of origin. Dates after 1 July by which the first 25 per cent of recoveries of young birds and adults from abroad are recovered have been used as an index of the arrival times of first-year and adult Black-headed Gulls from different countries in Europe (Table 11). In general, adults and young birds arrive on different average dates, but this is not constant for each country of origin and varies by more than 60 days. Young birds arrive earlier than adults from countries closer to Britain, but the reverse applies for those from more distant countries. This suggests that first-year birds start their migration earlier than adults but move much slower, perhaps making a series of short journeys interspaced with stopovers at rest areas lasting a number of days. In contrast, adults appear to make much longer flights to their wintering area and arrive in Britain from European countries at less variable dates. The interpretation of the trend line in Fig. 30 suggests that first-year birds on migration take about 43 days longer than adults to travel 1,000 km.

TABLE 11. Date by which the first 25 per cent of adult and first-year Black-headed Gulls ringed abroad have been recovered in Britain in each 12-month period, starting 1 July. Based on MacKinnon and Coulson (1986).

FIG 30. Difference in the dates of the first 25 per cent of recoveries in Britain of first-year and adult Black-head Gulls of Continental origin (data from Table 8) in each 12 months from 1 July, plotted against the distance from country of origin to central England. Note that the first-year birds from countries close to England arrived earlier than the adults, but that the converse was true for those travelling further.

Faithfulness to wintering areas

There is extensive and convincing evidence that some adult Black-headed Gulls from the Continent return to the same immediate wintering area year after year. The best example is a gull ringed in Poland, whose ring numbers were recorded in the same central London park over eight consecutive winters. However, such faithfulness to wintering areas is not absolute, as there are many instances of birds from the Continent wintering in Britain one year and then remaining in mainland Europe (usually in the Netherlands or Denmark) in the following winter (Fig. 31). It has been suggested, but not yet proven, that relatively mild conditions in western Europe in some recent winters have resulted in fewer Black-headed Gulls migrating here; this effect has also been reported for several species of waders and other waterbirds.

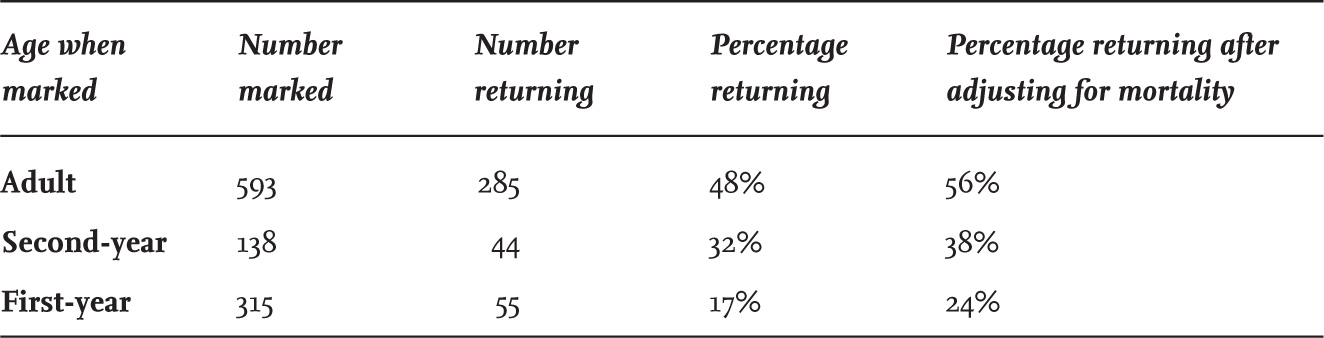

Evidence of the extent to which Black-headed Gulls use the same wintering area in successive years comes from individuals wing-tagged in north-east England, as these had a high probability of being seen if they returned in the following winter. Most tagged birds were breeding on the Continent, and so the annual return would involve many individuals migrating considerable distances. In the winter after tagging, those that returned were seen on an average of five different days, so it is unlikely that many others were missed. The study detected that 48 per cent of adults and 32 per cent of second-year birds, but only 17 per cent of first-year birds, returned to the same area in successive winters (Table 12). Allowing for mortality in the intervening year (estimated at about 15 per cent for adults and 30 per cent for first-year birds), 56 per cent of the surviving adults returned to the same wintering locality, with 38 per cent of those in their second winter when marked returning for a second time, but only 24 per cent of those marked in their first year.

FIG 31. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in Britain and recovered more than 20 km away in a subsequent winter. Many individuals returned to Britain, but note the appreciable number that failed to do so in a subsequent winter and were recovered on the Continent. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

TABLE 12. The proportions of marked Black-headed Gulls that returned to the same wintering area the following year.

A total of 38 marked individuals that did not return to the study areas were seen by other observers elsewhere in the winter following marking. These were reported mainly on the east coast of Britain, south of the study areas. Two extreme cases were recorded; one bird 450 km away on the south coast of England, and the other 300 km north at Aberdeen in Scotland. In addition, one remained in Denmark. It is evident from this that only a proportion of individuals of all age classes return to the same wintering area, but that faithfulness is stronger (although not complete) in adults. The reason why some birds return while others fail to do so remains unknown, but is not primarily related to their sex.

Return of birds to the Continent

The return migration from Britain to the Continent is much more synchronised than the arrival and begins in late March, with most adults migrating in April (Fig. 32). First-year birds tend to depart later than adults and some do not leave until May, while others (perhaps 10 per cent of immature birds wintering here) remain throughout the summer. These birds join the feeding adults associated with colonies in Britain (since they leave their wintering feeding areas) and presumably do not return to the Continent until they have overwintered here for a second time.

FIG 32. The month of arrival of Black-headed Gulls entering Britain from the Continent in autumn (white bars) and leaving in spring (blue bars), based on monthly change in numbers of ringing recoveries of foreign birds in Britain. Note that for all age classes, the spring departure is much more synchronised than the autumn arrival dates.

By the end of July, numbers of second-years have arrived in Britain and joined the few that spent the summer here. These birds are not constrained by breeding and moult about four weeks earlier than adults, so this might explain their early crossing of the North Sea. More arrive in late October and early November, and many late arrivals originate from further away, east of the Baltic.

Distribution of Continental wintering birds

The Continental Black-headed Gulls that winter in Britain do not disperse randomly across the country, and are much more abundant in eastern and southern regions. The proportions of young gulls ringed in Britain or on the Continent and recovered from December to February in each of 10 regions of Britain and Ireland (4,267 recoveries in total) were used to produce an index of the proportions of geographical distribution in each area (Fig. 33). The percentages of Continental birds in these different regions ranged from 7 per cent to 80 per cent, based on at least 115 recoveries in each region and, in most cases, many more. The wide range of percentages obtained suggests that they are a close approximation to the actual proportions of birds of Continental origin. Ireland, Scotland and Cumbria had low proportions of Continental gulls, while the highest proportions occurred in south Wales, southern England, and eastern England from Yorkshire southwards. Overall, about 71 per cent of the wintering gulls in Britain and Ireland originated from the Continent – a high value, but consistent with the much higher overall numbers of Black-headed Gulls reported here compared with estimates in the breeding season.

FIG 33. Estimates of the percentage of Continental Black-headed Gulls present in 10 regions of Britain and Ireland in winter based on numbers of recoveries of British and Continental ringed birds in each region between early December and the end of February.

Sex ratio of wintering birds

While the sex ratio of Herring Gulls and Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) captured in Britain during the winter approaches equality, that of wintering Black-headed Gulls shows a marked skew, with many more males being present. The data in Table 13 show that birds identified at breeding sites in northern England in May and June contained a minor excess of 108 males per 100 females. However, the sex ratio of wintering birds captured in England changed considerably, with a threefold excess of males in October and November, followed by the reversion of proportions to near equality between December to February. In the winter samples, most individuals were visitors from the Continent, and the skewed sex ratio in October and November suggests that either migrating males were arriving earlier than the females by an average of a month or more, or that males and females were feeding at different types of sites not sampled in those months, but were feeding at the same sites later in the winter. A total of 20 males and 11 females wing-tagged in the autumn were subsequently reported to have returned to the Continent, which gives some support for the suggestion that the bimodal pattern of the arrival time of Continental gulls (Fig. 32) represents males migrating earlier than females.

TABLE 13. The sex ratio of adult Black-headed Gulls cannon netted at landfill sites between October and February in north-east England, and near large colonies in northern England in May and June. Males were identified by a head and bill measurement of 82 mm or longer.

BREEDING BIOLOGY

Black-headed Gulls build their nest on the ground in areas with low-growing vegetation of varying density, ranging from sand dunes with much bare ground, to taller and floating vegetation around tarns and lakes. However, a few exceptions have been reported. At Seamew Crag, a small islet on Lake Windermere, Clive Hartley and Robin Sellers recorded several of the 50 pairs in the colony there nesting on top of low bushes over several years following 2009 (pers. comm.). In East Anglia in 1947, an entire colony numbering more than 300 pairs switched to nesting 2–3 m above ground level in young spruce trees, apparently in response to the flooding of their usual nest sites on the ground (Vine & Sergeant, 1948). Unlike some other gull species, there is only one old record of Black-headed Gulls nesting on a building, but in 2015 Robin Sellers found three small groups doing so, two near Perth and the other at Montrose, both in Scotland (pers. comm.).

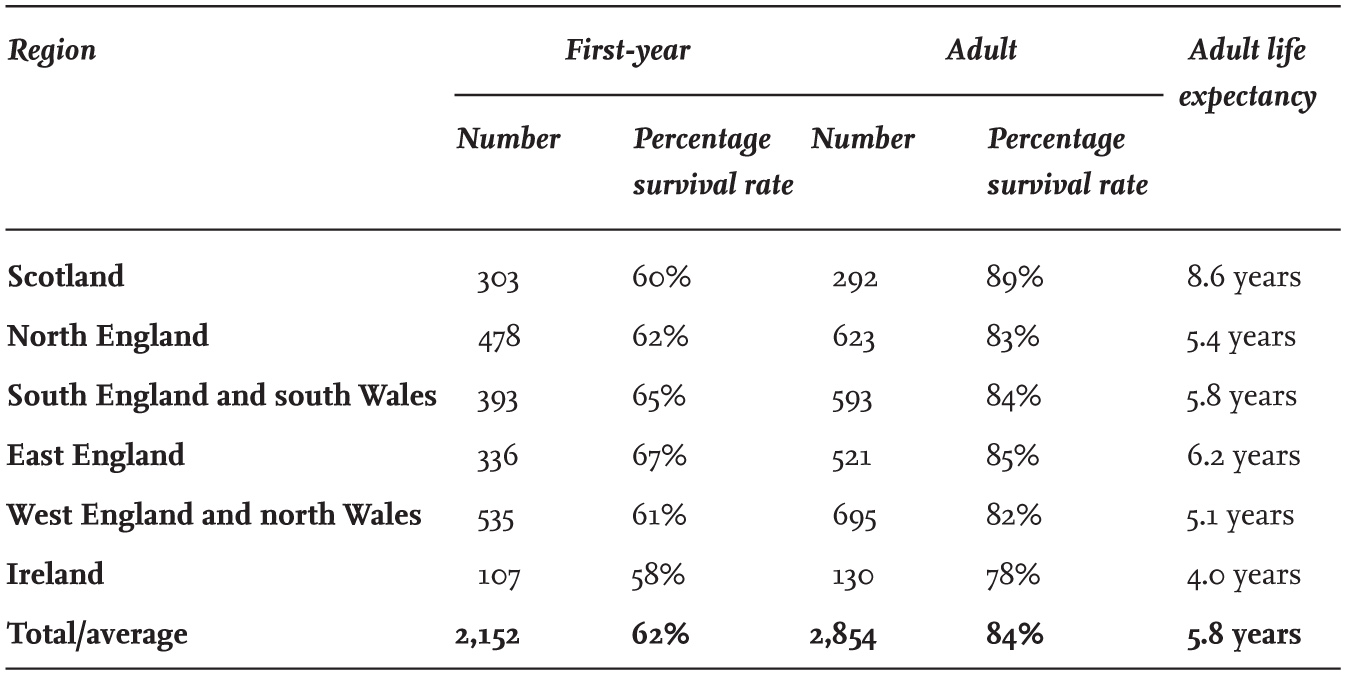

Philopatry and colony faithfulness

Most Black-headed Gulls are two years old before they breed for the first time and a minority are a year older before they breed. Exceptionally, one-year-old individuals attempt to breed, although their success is very low. Many of those that have survived to maturity return to breed in the colony in which they hatched as chicks (called philopatry), but others move to other colonies, often some distance away. The high proportion returning to the natal colony indicates that the young birds retain a good memory of where they were reared. However, it is easier to find marked individuals that have returned to their original colony than those that have moved elsewhere and consequently the extent of philopatry is often exaggerated. A realistic estimate of the extent of philopatry is obtained by measuring the proportion of those ringed as chicks and have reached adult age that were recovered during the breeding season less than 20 km from their natal site. In the case of the Black-headed Gull, about 60 per cent of the young that survive to breeding age are philopatric and the remaining 40 per cent move to other colonies and in a few cases, across the North Sea, to breed on the Continent. There have also been exchanges of individuals between Ireland and Britain (Fig. 34). Once adults have bred in a colony, their attachment to it becomes high, and at least 85 per cent of those surviving to the following year return to it to breed. The few adults that move elsewhere to breed are mainly from colonies that are in the process of being deserted, in some cases as a reaction to repeated nesting failure and the presence of mammalian predators.

FIG 34. Movements of more than 20 km of Black-headed Gulls ringed as chicks in Britain and Ireland and recovered in the breeding season when of breeding age. Many returned to breed at or near where they were reared, but a similar proportion apparently moved to other colonies. A few moved to the Continent to breed, mainly between northern France and Denmark, but one moved to Germany, another to Norway and a third to northern Sweden. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

Annual reoccupation of the colony

Black-headed Gull colonies are first visited by groups of adults in March each year. They arrive at irregular intervals during the morning, flying over the site without landing, and do not remain long at the colony or in the vicinity. Eventually, on one such visit some birds do land, but they exhibit a degree of nervousness and are easily disturbed. These visits become more frequent, but will be curtailed or prevented by cold and windy weather. As the days pass, the daily presence of the birds at the colony lasts much longer and spreads into the afternoon, but the colony is always vacated before sunset. The gulls usually leave by a synchronous ‘up’ or ‘panic’ flight, which sees them all suddenly rising high above the colony as if alarmed, yet without an obvious stimulus such as the appearance of a predator. As April progress, the amount of time the gulls spend at potential nest sites extends to the greater part of the day, but the colony is still deserted each night and reoccupied early in the morning, sometimes well before sunrise.

Pairs are formed early and courtship displays become common (Fig. 35). In the meantime, nesting material is collected locally and brought in to the colony. Birds nesting in some coastal colonies often collect substantial and untidy quantities of brown seaweed, while those at inland sites collect dry grass locally and carry it to the selected nest site to construct the nest. More material is usually added to the nest during incubation. Colonies and nesting sites are usually close to water, and nests are often substantial structures that raise the eggs above the local water levels.

FIG 35. Female Black-headed Gull (right) courtship-begging for food from a male. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

The density of nests varies according to the size of the colony and the nature of the nesting site. Nests are 1–2 m or more apart where plant growth is sparse, but only 50 cm apart in dense vegetation, presumably because this tends to conceal the neighbouring pair, moderating the extent of aggression between close neighbours.

Eggs and incubation

Black-headed Gull eggs are brown with spots of a darker colour. They are laid in mid- to late April (the date of the first egg laid in different years at Ravenglass ranged between 12 April and 26 April), but even at this time the colony is still often deserted at night, with the adults moving to night roosts and leaving the early eggs unprotected. As clutches are completed and incubation begins, increasing numbers of birds remain in the colony throughout the night; it is at this point that predation by Foxes on incubating adults may occur.

In Britain, the peak of laying in Black-headed Gulls is reached at the end of April or in early May, which is earlier than in other gull species breeding here. Fig. 36 shows the date distribution for the first eggs in each clutch recorded by Ian Patterson at Ravenglass (1965). There is considerable laying synchrony by the majority of pairs, but there is often a distinct tail or a secondary late peak of birds that re-lay after losing their first clutch or delay laying owing to inexperience.

The typical clutch comprises three eggs, although two-egg clutches are common. Occasionally, four-egg clutches occur, but whether these are laid by only one female has not been investigated. Late-laying birds produce clutches of just one or two eggs. Average clutch size within a colony varies considerably, from 2.3 to 2.8 eggs. Nils Ytreberg (1956) recorded a high average of 2.9 eggs from 411 nests in Norway, but in a later year reported a smaller average of 2.62 eggs based on a sample of 100 nests (Ytreberg 1960). The average clutch size tends to be lower in years when laying starts late, such as in small colonies and those further north and in the uplands. Eggs are laid at variable times throughout the day and the interval between eggs is usually about two days.

FIG 36. The spread of the laying season at Ravenglass, recorded by Ian Patterson in 1965. The secondary peak at the end of May/early June probably comprised repeat clutches produced by pairs that had lost their first clutch or by pairs of young, inexperienced birds.

Incubation of eggs and feeding of young is shared by both members of the pair. The eggs are covered by an adult irregularly while the clutch is still being laid, with the first egg probably protected rather than incubated. Obviously, incubation does not take place at night on occasions when the adults desert the colony in the evening. Intensive incubation starts at variable stages during laying of the clutch and often before the third egg is laid, but the brood patches of incubating birds are not fully vascularised for the first few days and initially the covered eggs may not reach a high enough temperature to facilitate development. This results in variable incubation periods, and the early start of incubation is sometimes enough to cause the third egg to hatch a day or so after the first two. Ivan Goodbody (1955) recorded incubation periods from the laying of the last egg of between 23 and 26 days at different nests.

Rearing young

A study by Roland Brandl and Ingrid Nelsen (1988) reported that Black-headed Gulls feed their chicks at intervals of about 45 minutes during daylight (but not at night), and that chicks receive at least 20 feeds each day. Each parent made five to six feeding trips per day, and obviously retained food from each trip for at least two feeding bouts. The authors found that this rate was mainly independent of the nestlings’ age or brood size. Adults regurgitate food onto the ground for the chicks and often re-swallow any surplus.

The newly hatched young have cryptically marked down, and as they grow, the feathers are patterned in shades of brown. The chicks remain in the nest for about a week if undisturbed and are brooded by their parents for a decreasing length of time each day as they grow older. Brooding at night often continues for a day or two longer after daytime brooding has ceased. Chicks eventually move a short distance away from the nest and shelter in nearby vegetation, where they receive some protection from both adverse weather and predators. One parent remains at the nest site most of the time, feeding the chicks by regurgitation and defending them against neighbouring adults and attacking wandering young from other pairs.

Once chicks reach 20 days old, they develop an interest in searching the ground for items they can pick up and swallow. Although they probably find little that is edible this way, the behaviour seems to develop their ability to search for food. Young birds can fly when they are about 34 days old and leave the colony area soon after fledging, often accumulating in small groups in open areas nearby. There, they search for food, later joining feeding flocks of adults in fields or on the shore. There is no evidence that the young are accompanied or fed by their parents once they leave the colony, nor do they return to the nest site to be fed after their first flight.

Breeding success

Breeding success in Black-headed Gulls is highly variable and depends on whether the colony is protected from predators, including humans. American Mink, rats, Badgers (Meles meles), hedgehogs, Foxes and herons are major predators at some sites, and are suspected to have caused the desertion of several colonies. Intensive predation can result in very few young fledging from a colony. For example, in a sample area at Ravenglass studied in detail by Ian Patterson, 2,213 pairs each fledged an average of only 0.06 young in 1961, while in 1963, 2,290 pairs each fledged an average of 0.10 chicks (Patterson, 1965). This poor breeding success was mainly caused by Fox predation on eggs, young and adults late in the breeding season.

At colonies where predation has been typically much lower than at Ravenglass, Black-headed Gulls probably fledge about 0.6–0.7 young per pair each breeding season. On its website, JNCC reports an average production of about 0.6 young per pair annually based on a few sample colonies studied between 1987 and 2015, but in the best year 1.2 chicks per pair fledged. Studies of several colonies over many years in France reported an average of 1.4 young fledged per pair (Péron et al., 2009). Once the last few young fledge, which is usually in late July or early August, colonies are rapidly deserted until the next breeding season.

FOOD AND FEEDING

Despite being small, the Black-headed Gull has been recorded feeding on a wide range of items, although in general these are smaller than those taken by the larger gulls. Animal material dominates, with invertebrates being by far the most frequently consumed food. Earthworms and the adult and larval stages of beetles and flies predominate in food obtained in fields. In coastal areas, marine crustaceans, molluscs and worms are frequently consumed when mudflats are exposed at low tide, or small food items are taken from the sea surface (Fig. 37). In addition to the consumption of animal matter, the gulls ingest a wide range of plant materials from time to time. Some of these are ingested incidentally with animal food, but seeds and grain are intentionally consumed – in autumn, for example, acorns are occasionally plucked from the tops of oak trees and Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) berries are picked off hedgerows by birds momentarily alighting on branches. A wide range of animal and vegetable materials, including bread, are taken around human habitation and at landfill sites. In some areas, bread and food scraps are regularly supplied by the public, particularly in parks and by lakes, and these form a major part of the winter diet in urban areas.

The gulls look for potential food either by flying 1–2 m over the ground or water and landing to pick up items, or (more frequently) by landing, usually as a dense flock in a field, where they spread out by walking over the ground. This latter habit is used extensively just after dawn, as soon as the gulls arrive from their night roosts and when earthworms are still active on or near the ground surface. Small fish and riparian insects are captured and consumed on or near freshwater sources. Insects such as swarming winged ants are caught in flight on calm days in late summer. At times, adults bring large quantities of hairy caterpillars collected from moorland to feed to their young, but the hairs of some of these species are irritants and many chicks regurgitate them in numbers, such that they sometimes litter the ground within the colony. Occasional small mammals and amphibians are consumed, but these form a minute part of the diet.

FIG 37. Black-headed Gulls feeding on small fish larvae. Note the unusual head position. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

Kleptoparasitism

Kleptoparasitism is common in Black-headed Gulls, whereby the birds steal from members of their own species and, particularly, flocks of Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus). Golden Plovers (Pluvialis apricaria) feeding on agricultural land in winter also regularly have their food stolen by the gulls. Lapwings and Golden Plovers feed mainly on earthworms and insect larvae obtained by actively searching the ground, and they are often joined by Black-headed Gulls (and sometimes Common Gulls, Larus canus). However, rather than searching for worms, some gulls just stand nearby or follow the plovers; when a plover finds a large food item that requires manipulation before it can be swallowed, it is rapidly and often successfully challenged by one of the gulls, and frequently the food item is stolen. In other cases, a plover may take off with the worm or insect in its bill, only to be closely pursued by a gull, which attempts to force it to drop the prey. When this happens, the gull takes the food as it falls or quickly turns to pick it up from the ground.

Such kleptoparasitism of Lapwings and Golden Plovers decreases the waders’ own rate of food consumption, but this is partially mitigated by feeding at night under full moon conditions when the gulls are absent. The fact that Black-headed Gulls resort to kleptoparasitism suggests that they are not as efficient as plovers at searching and finding their own earthworms.

Kleptoparasitism by Black-headed Gulls appears to be a specialised feeding behaviour used by a minority of individuals, and experience is important in successfully obtaining food in this way. Even by their second year of life, young Black-headed Gulls have still not achieved the efficiency of adults when carrying out kleptoparasitic attacks (Hesp & Barnard, 1989).

In urban areas in winter, the tables are often turned on Black-headed Gulls. Those birds finding large food items that they fail to swallow immediately are frequently pursued by Common Gulls or even members of their own species, until they are forced to drop the food to the benefit of the pursuers. Such pursuits are particularly frequent in urban areas during severe winter weather, when large numbers of Common Gulls move from snow-covered high ground and congregate at much increased densities at urban feeding sites.

Feeding areas

In the breeding season, the feeding areas and ranges of Black-headed Gulls are limited by the location of the colony, and well-defined flight lines are often evident to and from large colonies. Many feeding adults forage within 10 km of the colony, although some will travel 40 km or more to favoured sites with a regular supply of food provided through the activities of humans. These may be fields where ploughing is in progress, landfill sites, large car parks (particularly near food stores), coastal picnic sites or riverbanks in towns where people feed bread, chips and other items to birds. Food supplements put out for farm animals are also exploited. Few Black-headed Gulls hunt far from the shore at coastal sites, and only rarely do they plunge-dive and submerge to capture fish.

In the 1960s, along the 18 km tidal reaches of the river Tyne (which was little more than an open sewer at the time), Black-headed and Common gulls were the commonest birds feeding in winter at sewage outfalls and on sewage items floating in the river. Once the sewage was piped separately to treatment plants to clean the river up, the numbers of Common Gulls reduced dramatically, but Black-headed Gulls remained abundant and were still able to find food in the river. This is because the outflow of filtered water passing from sewage plants into the river still contained small items, which were attractive to the Black-headed Gulls but not the Common Gulls.

The habit of large numbers of Black-headed Gulls following tractors ploughing fields is both widespread and spectacular, with many individuals competing for position just behind the plough blades, and diving to catch and consume worms or insects exposed when the soil is turned over. Similar feeding occurs when grass is being cut for hay. The introduction of grass cutting earlier in the year for silage attracts many Black-headed Gulls and has had a marked effect in some areas where the birds feed. Although silage production was introduced many years ago, it became far more extensive from about 1969, and by 1993 it had increased sevenfold as a means of producing winter cattle feed. Grass is now frequently cut twice a year for silage and much earlier in the season than for hay. This has allowed feeding by Black-headed Gulls on insects in these fields to be spread over a much longer period of the species’ breeding season than was once the case, and presumably has been of benefit to the gulls.

Feeding at landfill sites in winter attracts flocks of hundreds and even thousands of Black-headed Gulls. It is a highly social activity and occurs at irregular intervals, often with a resting, inactive flock remaining nearby for long periods. From time to time, one or two individuals leaving the flock will then fly over the landfill working area and alight there or pick up a food item while in flight. This act of feeding by one or two individuals is a major stimulus to those birds in the resting flock, and the great majority will then leave the roost and stream over to the feeding site, land on the refuse and search for food – several hundred individuals may be highly active within a small area. Suddenly, feeding will stop, perhaps as the result of a loud noise, the approach of a person or the arrival of a lorry. On other occasions and for no apparent reason for alarm, the flock will rise as one and return to the roosting site, staying away from the landfill working area for many minutes or even hours.

Food-collecting techniques

Black-headed Gulls use several techniques when collecting food, summarised below:

1. Aerial searching Individuals patrol suitable areas, turning and swooping to pick up items discovered. Used on farmland and in urban areas.

2. Walking over fields of short grass The birds are usually spread out and search for food items on the ground.

3. Feeding while floating on water The birds swim buoyantly, turning rapidly to pick small items such as larval fish from the water’s surface, phalarope-like (Fig. 37). Head-dipping into the water is less frequent and diving does not take place.

4. Feeding frenzies Many individuals converge on an appreciable food source, such as food discarded by the public, a freshly ploughed field or refuse at a landfill site. In all three cases, individuals are attracted from some distance by the erratic flight and calling of those birds already scrambling for food.

5. Feeding on flying insects This is most frequent in autumn, when winged ants take to the air on calm, warm days. The gulls ‘hawk’ after the insects, flying slowly and frequently changing direction.

6. Consumption of items from trees, bushes and low plants This is an infrequent method, with gulls approaching branches or low plants, landing on them momentarily, and plucking abundant insects from the leaves and thin branches. Similar methods are used to obtain acorns from oak trees and berries from Hawthorn bushes.

7. Paddling in shallow pools on intertidal mud This technique is used to disturb, detect and capture small invertebrates, including marine worms. While Herring Gulls also use this method on areas of short grass, this has not been reported in Black-headed Gulls.

8. Kleptoparasitism The birds steal food from Lapwings and Golden Plovers when the waders are feeding on soil invertebrates in pastures.

Use of winter feeding areas

The next sections are based on data gathered through extensive ringing and wing-tagging studies of Black-headed Gulls wintering in north-east England. Observing coloured leg rings on Black-headed Gulls was difficult in resting flocks and when they were feeding on grasslands, so to overcome this problem, plastic wing tags were used (here). These proved more successful in identifying and following the behaviour of individuals throughout the day. The collaborative research involved identifying feeding areas and catching and marking birds prior to and during three years of intensive field studies on the species made, and was carried out by Gabriella MacKinnon at Durham University as part of her doctoral thesis (MacKinnon, 1986). It involved us in many cold early-morning starts in winter to reach the feeding areas and set cannon nets before the gulls arrived at about sunrise from their night roosts.