APPEARANCE

The Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) is the largest gull in the world, with a wingspan of more than 1.5 m. In older literature and occasionally in current accounts, it is called the Greater Black-backed Gull, presumably to be consistent in separating it from the Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. fuscus), with which it was confused in the nineteenth century.

Adults are readily identifiable by their large size and their black wings and mantle, whose colour is as intense as on the wing-tips. In addition, they have a substantial, powerful bill (particularly so in the males), and the flesh-coloured legs prevent confusion with the Lesser Black-back, which has yellow legs (Fig. 100). The adult’s bill is yellow with a red spot on the lower mandible, as in the Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) and Lesser Black-backed Gulls. The voice is gruff and deeper than that of other gulls, and once it becomes familiar, the bird’s presence can readily be identified when flying and calling overhead among flocks of mixed gull species.

FIG 100. Fourth-year Great Black-backed Gull (left) and similar-aged Lesser Black-backed Gull (Larus fuscus). (Nicholas Aebischer)

Juveniles and first-year birds (Fig. 101) have the typical flecked, camouflage plumage of immature large gulls, but the background colour is grey (rather than brown as in Herring Gulls) and it has a more distinct chequerboard patterning. Caution is necessary, however, because some first-year male Herring Gulls are similar in size to female Great Black-backed Gulls of the same age.

The bill is totally dark in recently fledged birds, and a small, light area at its base becomes more extensive during the second, third and fourth years. The second- and third-year birds progressively acquire more adult plumage; they already have white heads and breasts at this age, but still retain some immature feathers on the wings and mantle, despite having acquired some totally black feathers. Fourth-year birds have still not assumed full adult plumage (Fig. 100), and while the bill is now mainly yellow, there is often a dark spot on the lower mandible that in full adults turns red.

FIG 101. First winter Great Black-backed Gull. (Nicholas Aebischer)

DISTRIBUTION

The Great Black-backed Gull is restricted to the North Atlantic and adjacent seas. It breeds in northern Europe and along part of the east coast of North America, and its distribution includes Greenland, Iceland, the Faeroes and as far north as Svalbard and Bear Island. In Europe, it is mainly a coastal breeder, nesting along the northern seaboard from north-west Russia to northern France, which it colonised in 1920, at the same time as it spread to Svalbard and Denmark. In North America, the species has spread north to Nunavut in Canada and south on the east coast of the USA as far as North Carolina. Numbers worldwide have been estimated at about 340,000 adults.

The species is sedentary over much of its range, including North America, Greenland, Britain and Ireland. However, birds breeding in north-west Russia and many from the Norwegian coast migrate in winter into the North Sea and the adjacent countries. In general, the species is increasing and slowly expanding its range on both sides of the Atlantic, helped by the fact that it is now not hunted except in Denmark.

The BTO census in Britain and Ireland in 2007 showed that breeding Great Black-backed Gulls have a marked western distribution, with concentrations on islands of various sizes in the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland, and on the mainland of northern Scotland (Fig. 102). There is also a strong western distribution in Ireland and in Wales, from where the range extends into south-west England. At that time, some 34,000 adults were reported breeding in Britain and Ireland. In the past, Great Black-backed Gulls used to breed inland, but these colonies were reduced or exterminated by upland sheep farmers and gamekeepers, who considered the gulls a threat to livestock, and only 40 were nesting inland in 2000.

In the last 20 years, the species has increased its range and spread along the east and west coasts of Scotland, into north-west, north-east and south-east England. This expansion was delayed by culling of large gulls in the Firth of Forth, particularly on the Isle of May in Scotland, the Farne Islands in Northumberland and at Abbeystead in Lancashire, where small numbers of breeding Great Black-backs were killed during culls of other gulls. In addition, numbers were killed on Skomer and Skokholm, off the south-west coast of Wales, to reduce predation on Manx Shearwaters (Puffinus puffinus). The species has also spread within Ireland, particularly along the south and north-east coasts, and it now breeds (albeit in small numbers) around most of the coastline.

New Great Black-backed Gull breeding areas are usually established by a single pair joining existing colonies of Herring Gulls or Lesser Black-backed Gulls, followed by an increase of numbers in later years. This occurred at the large inland gull colony at Abbeystead and has been recorded on the coast at many sites, including the Isle of May, the Farne Islands, Orford Ness and Havergate Island in Suffolk, Rockcliffe Marsh in Cumbria and on the Ribble Estuary in Lancashire.

FIG 102. Map of the breeding distribution of the Great Black-backed Gull in Britain and Ireland 2008–11. Reproduced from Bird Atlas 2007–11 (Balmer et al., 2013), which was a joint project between the British Trust for Ornithology, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. Channel Islands are displaced to the bottom left corner. Map reproduced with permission from the British Trust for Ornithology.

Biometrics

Biometrics of Great Black-backed Gulls recorded in four studies are shown in Table 48. From this, it can be seen that the average wing lengths of Great Black-backed Gulls of both sexes breeding in Wales, Norway, north-west Russia and North America are nearly identical. This is in contrast to Herring Gulls – and Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) and Puffins (Fratercula arctica) – which conform to Bergmann’s rule and are appreciably larger in arctic Europe than in Britain. One effect of this is that males of the large Herring Gulls breeding in northern Scandinavia are of similar size to female Great Black-backed Gulls breeding in the same area, which could potentially result in greater competition between them than in Britain. The similar size of Great Black-backed Gulls over much of their range meant that the birds caught in winter from unknown breeding areas could be sexed with about 98 per cent accuracy based on their head and bill measurements and, if necessary, confirmed by wing length. Head and bill length alone correctly sexed 95 per cent of individuals.

TABLE 48. The biometrics of adult Great Black-backed Gulls breeding in Norway, north-west Russia, Wales and on the east coast of North America, compared with those breeding in Scandinavia and captured in winter in north-east England.

Historical distribution in Britain and Ireland

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe and North America, the Great Black-backed Gull was persecuted and its numbers were much reduced. Feathers were used in the hat trade and for bedding, and in upland Britain the fully grown birds were also considered a threat to lambs and gamebirds and were consequently killed, while some birds were shot for no reason other than that they were suitable targets. As a result, the species was extirpated from appreciable parts of Britain.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, numbers of Great Black-backs in Britain and Ireland probably reached their lowest level. A recovery then began, although it came about much later and was much slower than for other gull species because persecution continued in many areas. Distribution had been reduced to three isolated groups: one in south-west Wales and south-west England, including the Scilly Isles; one in the west of Ireland; and a third (and by far the largest) group on the islands and mainland of western and northern Scotland. As numbers increased slowly through most of the twentieth century, the species gradually returned as a breeding bird to a few areas from which it had been extirpated.

By 2000, more than three-quarters of breeding Great Black-backed Gulls in Britain were in Scotland. There were still extensive areas – including much of the east coast of Scotland and England, north-west England and south-west Scotland – where they were few or absent, but several of these have since been colonised. Despite this recovery, the national census in 2000 hinted that a small decline in the totals breeding in Britain and Ireland might have occurred since 1985, although this perceived decrease may simply reflect an incomplete coverage of the census and the considerable difficulty in making accurate counts of the species.

Great Black-backed Gulls have begun to nest on buildings in towns, but more recently and in much smaller numbers than Herring and Lesser Black-backed gulls. In 1976, only seven pairs were recorded nesting on buildings at three localities in Britain. By 1994, the total had increased to 11 pairs at 10 sites, but numbers in Cornwall were not recorded at that time. By 2000, numbers nesting at urban sites had increased to 83 pairs at 26 sites, with most in Devon and Cornwall, but seven urban nesting pairs were reported in Scotland and a single pair nested for the first time on a building in Wales. Although no national census has been carried out since, other towns and cities in Scotland and England now have nesting Great Black-backed Gulls, including Dumfries in south-west Scotland, Edinburgh in south-east Scotland and several towns in Cumbria. Pairs often select a higher point for nesting than other large gulls, such as flat roofs, on top of lift shafts or on other similar structures that are raised above the main roofs of the town, similar to their tendency to use raised areas at natural sites.

FIG 103. The date on which the first egg of each clutch is laid by (a) American Herring Gulls (Larus smithsonianus) and (b) Great Black-backed Gulls breeding in the same colony. Data from Erwin (1971).

BREEDING

Great Black-backed Gulls tend to lay one or two weeks earlier than American Herring Gulls nesting in the same area (Fig. 103), with many of their clutches started during the second half of April and early May. The usual clutch size is three eggs, and as two-egg clutches are less frequent than in Herring Gulls, this results in a slightly larger average clutch size compared to that species, with 2.9 eggs laid in Wales on average and 2.8 eggs in North America. As is the case with many other gull species, lost clutches are usually replaced. Incubation from completion of the clutch takes about 27 days. Incubation and feeding of the young is shared by both parents, but neither the frequency of feeding nor the pattern of duty sharing by the sexes have been investigated.

The growth of the chicks follows a typical pattern for gulls. After a slow start (with the chick relying on, and benefiting from, some yolk still present after hatching), there is an appreciable period of constant increase in weight each day of about 42 g, the largest daily weight gain recorded for any gull species. The third stage sees progressively lower daily growth rates, until a maximum weight is reached just before fledging (Fig. 104), which is slightly below the adult weight and persists for several weeks or even months. It is not recorded how long the young are fed by their parents after fledging, but in some cases they return from time to time to the nest site and are fed there by the parents. Owing to the large size of the adult Great Black-backed Gull, growth and development during pre-fledging are spread over a long period of about 50 days before sustained flight is achieved, giving a longer fledging period than in any other gull species. If undisturbed, breeding success is often high, with an average of more than one chick fledged per pair; in some areas, averages of up to 1.4 fledged per pair have been reported.

There is little information on the age of first breeding of this species. Some accounts state that breeding occurs at four years of age, but no details are given. However, if the species is like other large gulls, there is probably considerable variation, with some individuals being five or even six years old before they nest for the first time.

Apart from detailed research of their feeding habits, Great Black-backed Gulls remain the least-studied breeding gull species in Britain. In part, this is because they breed in relatively inaccessible sites and at low densities. The species is seen as a top predator that has adverse effects on other birds, and rather than encouraging study, this has often resulted in the removal of eggs and culling of adults in an attempt to benefit other species. It is also the least colonial of British gulls, often breeding as isolated pairs on small islands that are difficult to access, or within colonies of other large gulls. Studies to assist management have begun on the breeding biology and survival rates of this species on Skomer and Skokholm, leading to a change in conservation policy on these islands following many years of culling and egg removal.

FIG 104. The typical growth rate of a Great Black-backed Gull chick (indicated by the continuous line) and the limits of normal variation, some of which is probably caused by the sex of the chick (indicated by the dotted lines). Some chicks return to the nest site and are fed after fledging, but it is not known how regularly or frequently this occurs. Adult males weigh 1,820 g on average, and females 1,500 g.

In some places, the Great Black-backed Gull does nest colonially, but at lower densities than other gulls. In Britain, colonies seldom number more than 100 pairs; the largest colony was reported by P. G. H. Evans in the early 1970s on North Rona, a small island 80 km off the north-west coast of mainland Scotland, with about 2,000 pairs. However, numbers there had declined to 1,000 pairs by 2000 and then to fewer than 200 pairs within the past 10 years. Copinsay, in Orkney, was reported to have just over 1,000 breeding pairs in 2000, but numbers have since also declined there.

On the east coast of North America, colonies of Great Black-backed Gulls are often larger than in Britain and a few of these have been subjected to detailed studies. One investigation showed that breeding success was appreciably higher in pairs nesting on the edge of colonies compared to those in the centre, which is the opposite to findings in several other species of gulls. It was also reported that their breeding success was twice as high when their nearest neighbours were American Herring Gulls (Larus smithsonianus) rather than other Great Black-backs. In both cases, the differences were attributed to the aggressive and cannibalistic nature of the Great Black-backed Gulls.

MOVEMENTS

Recoveries of nestlings ringed in Britain show that most make only modest dispersals of a few hundred kilometres within the country, although a few marked in north-east Britain did leave the country, crossing the North Sea. Four of these birds moved to the Faeroes, one reached Iceland and two moved to Ireland (Fig. 105). Of those marked in south-west Britain or in the south of Ireland, a few moved to the Bay of Biscay and only two travelled further and were recovered in Spain (Fig. 106). Despite the fact that appreciable numbers have been ringed on both sides of the Atlantic, there are only two recorded transatlantic crossings. These were a young bird reared and marked on the east coast of Canada, which was recovered in Portugal, and an adult ringed in Newfoundland as ‘fully grown’ in July 2006, which was found dead near Plymouth, England, eight months later.

FIG 105. The movements of Great Black-backed Gulls ringed in north-east Britain during the breeding season and recovered in the non-breeding season. The bold black line shows the area within which they were ringed. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

FIG 106. The movements between the breeding season and non-breeding season of Great Black-backed Gulls ringed or recovered in SW Britain and southern Ireland. The bold black lines show the areas of ringing. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

FOOD AND FEEDING

Apart from feeding occasionally on berries in summer and early autumn within the Arctic Circle, the Great Black-backed Gull’s diet comprises entirely animal material composed of the greatest range of foods recorded for any species of gull. They are opportunists, and exploit the whole range of food consumed by Herring and Lesser Black-backed gulls; in addition, as a top predator, they consume large items that are not normally taken by the other species, including a wide range of fish, birds and small mammals.

Most studies have found that fish is the most important component of the diet, and judging from the species and sizes, most are obtained as discards from fishing vessels. That said, in some areas of the North Atlantic the gulls follow shoals of large predatory fish and marine mammals to capture fish driven to the surface by these marine hunters. Presumably, Great Black-backed Gulls must have caught most of their food in this way in the distant past. Where the gulls breed in large colonies of other seabirds, fish are less frequently consumed and are replaced by young and adult seabirds and Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), which can form a major part of their diet at some sites during the breeding season. The Great Black-backed Gull is capable of killing and consuming an animal half its own size. Such large food items are dismembered, whereas smaller items – such as fish and young seabirds – are usually swallowed whole and indigestible parts are later regurgitated in pellets.

Historical and recent accounts have claimed that adult Great Black-backed Gulls kill fully grown sheep. These reports are almost certainly a misinterpretation of the situation where the gull is seen standing near or on a sheep that has died from other causes, and confirmed cases of gulls actually killing adult sheep are lacking. Great Black-backed Gulls will feed on the carcasses of large animals such as a sheep or seals, and are known to have attacked animals that are already seriously ill, such as lambs and gulls of their own species. In 2015, the media reported that a ‘giant gull’ was attacking adult sheep in Ireland, with the story occupying many columns of newsprint for several days. Observations of what actually occurred were not reported. The suspicion that large gulls, and Great Black-backed Gulls in particular, are a threat to sheep and gamebirds in the uplands, whether real or otherwise, accounts for their disappearance from many former inland breeding areas where they once bred in the past.

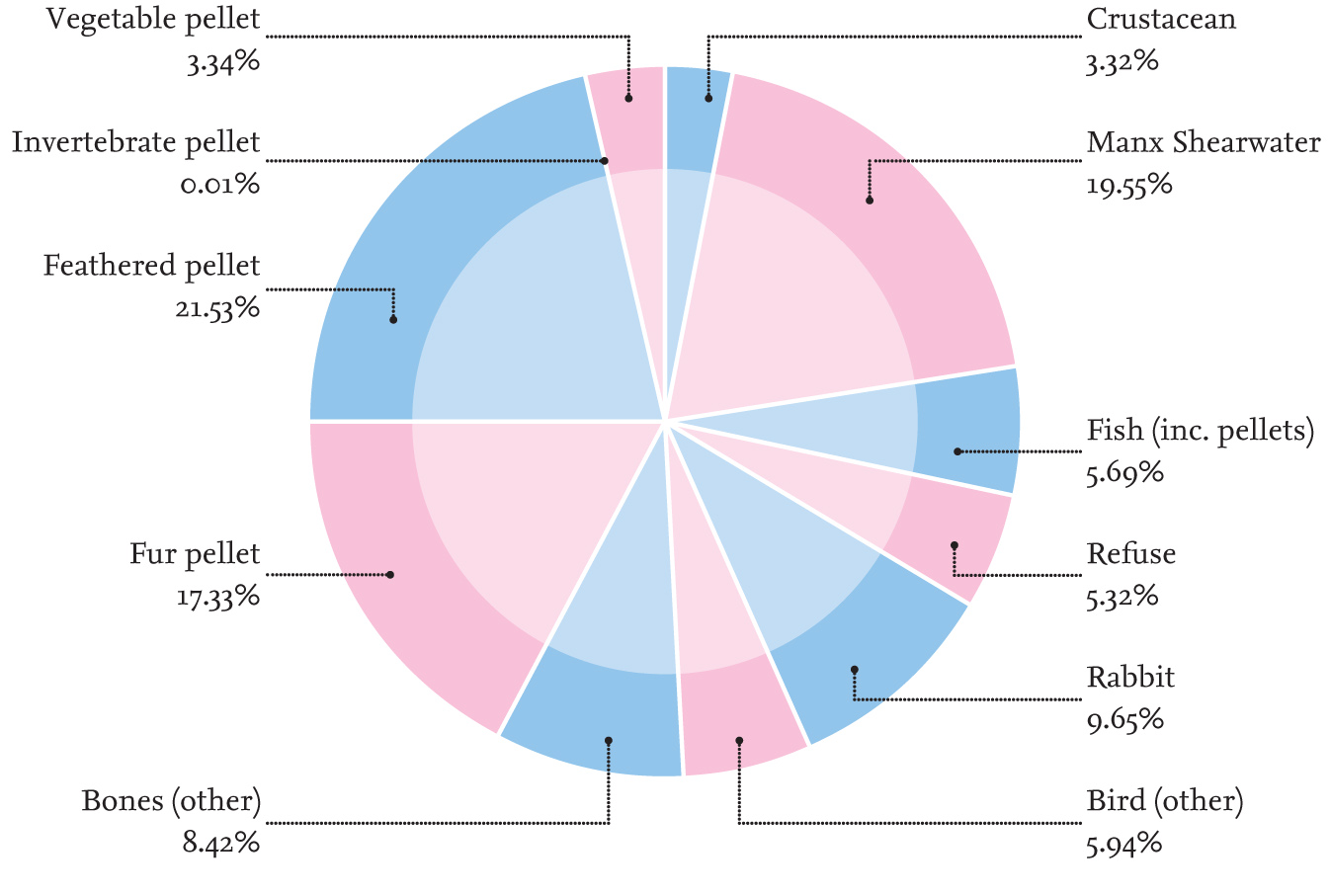

On islands such as Skomer in Wales, where Great Black-backed Gulls breed alongside other species, adults prey during daylight on a broad spectrum of seabirds. In addition, Manx Shearwaters and Storm Petrels (Hydrobates pelagicus) are killed at night and in the early morning when they visit burrows and nest sites near the nesting gulls. Many of the shearwaters killed are prospecting young birds that are preparing to breed for the first time, and the extent of this mortality has been a cause of concern. A survey funded by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee found that 92 per cent of Great Black-backed Gull territories on Skomer contained remains of shearwaters at the end of the breeding season (Fig. 107), and that each pair of Great Black-backed Gulls was killing an average of eight Manx Shearwaters and three Rabbits each year. Adult Puffins were also captured and consumed, both on land and at sea, but numbers could not be determined. The diet of the Great Black-backed Gulls nesting on Skomer in 2013 was grouped into 11 types of food (Fig. 108). From this, it can be seen that fish, birds and Rabbits formed substantial parts of the diet. However, food regurgitated by Great Black-backed Gull chicks before they fledged showed that much more fish was present than in the adult diet. Presumably, the young were being fed with food obtained on feeding trips, while predation on seabirds represented food captured and consumed by adults in the colony mainly for their own maintenance.

In an attempt to protect Manx Shearwaters, numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls were culled on Skokholm between 1949 and 1985, and on Skomer during the 1960s and 1970s. As a result of these management policies, numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls nesting on Skomer were reduced from about 280 pairs in 1960 to 25 pairs in 1984. An outbreak of botulism in the early 1980s also contributed to their decline, but since then numbers on Skomer have gradually recovered to about 100 pairs. Numbers breeding on Skokholm were reduced to about five pairs in 1968, but since culling stopped in 1985 they have increased to 92 pairs. The large numbers of shearwaters nesting on these islands appear able to tolerate the current level of predation by Great Black-backed Gulls without declining.

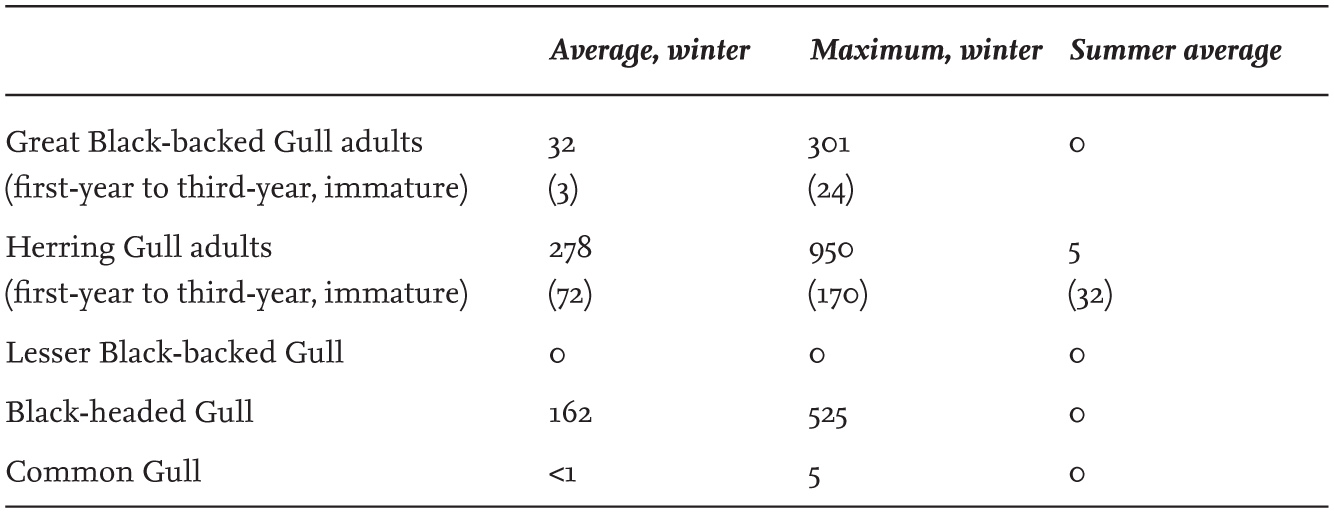

Over much of the year, Great Black-backed Gulls are offshore feeders and frequently in attendance near fishing boats, particularly while nets are hauled in and unwanted fish are discarded. While Herring Gulls and Lesser Black-backed Gulls are often abundant around inshore fishing vessels off the British coast, on some occasions they are outnumbered by Great Black-backed Gulls. Up to 1,000 Great Black-backs have been recorded around single fishing boats off Shetland and in the Irish Sea (Table 49), but in contrast they are infrequent around fishing boats off the east coast of England in the summer.

FIG 107. The number of Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) found per pair of Great Black-backed Gulls on Skomer, south-west Wales, in 2008–15. Data from the JNCC website.

FIG 108. Evaluation of the food of Great Black-backed Gulls breeding on Skomer, south-west Wales, in 2012. The numbers are estimates of the percentages of the total food obtained from these organisms. Data from the JNCC website.

During the breeding season, the Great Black-backed Gull occurs further offshore than the other large gulls, although in much reduced densities beyond 25 km from the nearest European coastline. Birds breeding in Newfoundland have been recorded travelling 100 km and more from land to feed near fishing boats working in areas of the Grand Banks. In winter, individuals have occasionally been reported up to 200 km from land, but these records are restricted to the continental shelf, which is still essentially associated with the fishing industry. The limited distance Great Black-backs move offshore (which prevents the species from being considered pelagic) is probably determined by its strong preference to roost at night on land or in sheltered waters along the coastline, although there are a few records of birds remaining offshore and feeding at night within the North Sea.

TABLE 49. The average numbers of seabirds attending each trawler fishing for white fish off Scotland and in the Irish Sea in summer and winter. Data mainly based on Hudson & Furness (1989) and my unpublished data for north-east England.

Commercial fishermen discard fish from their vessel for a variety of reasons: because the fish are below the minimum legal or marketing size; because fish escape from nets as these are hauled in; because there are restrictions on the percentages of catch that can be landed; and because of fish quotas. Some fishermen attempt to maximise their financial returns by keeping only fish that will sell for the highest price and discard the rest. As part of the reformed Common Fisheries Policy, catches of undersized quota fish may no longer be discarded in European waters. Instead, all of the catch must be landed and counted against the quota. This new rule was implemented in 2015 and will become more widespread and more wide-ranging up to 2019, including part of the Atlantic Ocean, and the Baltic, North and Mediterranean seas. These changes are likely to have a major impact on several seabird species, particularly on numbers of large gulls and Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis). The current dependence of Great Black-backed Gulls on commercial fisheries is likely to affect them now and into the future, as a result of major changes in the intensity and methods of fishing, and particularly the new regulations. Already, declines in numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls have been reported from parts of the east coast of Canada, associated with decreased commercial fishing activity. On Canna in the Hebrides, numbers of breeding Great Black-backed Gulls declined by 80 per cent between 2000 and 2009, a reduction attributed to much lower fishing activity and smaller landings of fish at nearby ports. A national census is needed to explore whether such declines have occurred elsewhere and that the reported changes in numbers are not the result of some other cause, such as disease.

There are few records of Great Black-backed Gulls catching fish at sea apart from at fishing vessels, although this may be because there are few observers offshore. Some individuals are attracted to, and feed on, surface shoals of sandeels when these are also attended by other gull species, and they will plunge from the surface or make shallow dives from flight after other fish, although the depth of the dives appears to be less than 1 m.

As mentioned above, small food items are also consumed by Great Black-backed Gulls and the variety of items they take is almost endless. Refuse and carrion are also consumed, and kleptoparasitism (parasitism by theft) on smaller gulls and even their own species is common, particularly by males. Many prey are captured alive, but the birds are also major carrion feeders, exemplified by the frequent occurrence of this species feeding on fish offal at sea, at fish docks and at landfill sites (see below).

The diet of Great Black-backed Gulls breeding on Cape Clear Island, Ireland, was investigated by Neil Buckley (1990). He reported that it comprised mainly fish and birds, as on Skomer (see above), but in the absence of Rabbits and shearwaters, 90 per cent by weight of the food was fish and auks, the former being mainly obtained from fishing boats. Other foods represented only 10 per cent of the diet and included small mammals, crabs and goose barnacles.

Breeding areas of Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus) where pups are born in late autumn and early winter are frequented by Great Black-backed Gulls (often together with Grey Herons, Ardea cinerea), which feed on the afterbirths and, less frequently, on dead young seals. The species is undoubtedly opportunistic, exploiting whatever is available.

Feeding at landfill sites

Although the Great Black-backed Gull is rarely the most numerous gull attending landfill sites (Table 50), and numbers vary markedly from day to day, it is the dominant species when present because of its sheer size and aggression. Some male Great Black-backs feeding at landfills frequently use kleptoparastism as the main method of obtaining food. Instead of rummaging through the refuse, they frequently stand on a raised site within the feeding area watching out for other gulls taking large food items they cannot swallow quickly. The forager is then attacked and pursued by the Great Black-backed Gull, which is usually successful in stealing and swallowing the item. Susan Greig studied this kleptoparasitic method of feeding by using video recordings (here) and found that the average rate of swallowing food was higher in Great Black-backed Gulls than in Herring Gulls of all ages. This was mainly achieved through kleptoparasitism, which was successful in 99 per cent of 333 attacks on individuals of other gull species and much more so than the fewer attempts made by Herring Gulls. The latter were much more abundant on all occasions and received many attacks from Great Black-backed Gulls, but attacks between two Great Black-backed Gulls (often a male attacking a female) also occurred and, surprisingly, were more than twice as frequent than would have been expected. Herring Gulls usually attacked their own species to steal food and rarely attacked Great Black-backs, but when they did so, the attempt almost always failed. Presumably, Herring Gulls soon learn to recognise Great Black-backed Gulls and regard them as unprofitable targets for kleptoparasitic attacks.

TABLE 50. The average numbers of gull species present at one landfill site during a working day in north-east England (Northumberland and Durham) in winter (October to the end of January) and summer (April to July). Note that the three year classes of immature Great Black-backed Gulls and Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) formed only a small proportion of the total number of individuals of those species in winter.

Frenzy feeding by gulls at landfill sites rarely extended uninterrupted for more than 20 minutes. Studies by Greig found that the feeding rate of Great Black-backed Gulls was high during the first 10 minutes but then declined by 30 per cent (based on 820 records), whereas it decreased by only 10 per cent in Herring Gulls when feeding continued beyond 10 minutes. Presumably, the exposure (and hence availability) of large food items declined rapidly during the feeding frenzy, which involved many gulls, and this affected the feeding methods of Great Black-backed Gulls more than Herring Gulls. Only when new material was dumped, or the existing material was disturbed by the compactor, did the feeding rates increase again. This rapid removal of suitable food items and the subsequent decline in the feeding rate may explain why many feeding frenzies ended spontaneously within 20 minutes, even when there was no human activity or other disturbance at the working face.

There is no doubt that where large numbers of Great-backed Backed Gulls nest within seabird colonies (and these are few), their impact on the breeding success of their own and other species is considerable. Prey species involved include Puffins, Manx Shearwaters, Kittiwakes, Northern Fulmars and even other larger gulls. Dead chicks of their own species are frequently consumed by large Great Black-backed chicks in the last two weeks before they fledge.

In areas of Scotland, such at the mouth of the river Ythan near Aberdeen, and at several localities on the east coast of Canada and the USA, studies have revealed that predation by Great Black-backed Gulls (and other large gulls) is responsible for the high mortality of Eider (Somateria mollissima) ducklings and is believed to have caused declines in local numbers of Eiders. Kleptoparasitism by Great Black-backed Gulls on flocks of Eiders diving for food is also common. The gulls sit on the water near a flock of feeding ducks and wait for one to surface with a large prey item that cannot be swallowed underwater (such as crabs, whose legs must be removed by the Eider before it can swallow it), before attacking the duck and usually forcing it to relinquish its prey.

Feeding behaviour in winter

Regular winter counts of Great Black-backed Gulls visiting inland landfill sites in north-east England have revealed that the numbers present varied dramatically from day to day, and much more so than the numbers of Herring Gulls and Black-headed Gulls (Chroicocephalus ridibundus). For example, a single bird present on one day was replaced by more than a hundred on the next day, and then numbers decreased to three on the following day. These large fluctuations were first noted by Pat Monaghan during her study of gulls feeding at the inland Whitton landfill site in County Durham. Later counts at a series of landfills in north-east England confirmed the frequency of these fluctuations, with, for example, between one and 298 individuals present at a site on five consecutive days in the same week. Two examples from Coxhoe landfill in County Durham of this extreme variation occurring within a week are shown in Fig. 109. Counts at other landfill sites in the area and day roosts on the coast showed a close positive correlation with the numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls at Coxhoe: when numbers were low there, the missing birds were not visiting other landfill sites, and on some occasions were reported moving offshore to feed behind fishing boats.

Great Black-backed Gulls in north-east England roosted at the coast each night and chose at dawn whether to go to sea or move inland in search of food at landfill sites. Susan Greig used a large database of daily counts collected by others at inland landfill sites in north-east England to identify the environmental factors that correlated with variations in numbers. She found that the most important relationship was wind strength during the night, which was positively correlated with large numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls visiting landfill sites on the following day. Gales kept many fishing boats in harbour, which significantly reduced scavenging opportunities for gulls. Most of the Great Black-backed Gulls arrived at inland landfill sites within two hours of sunrise, and presumably they used the wind speed at night or at dawn as an indicator of the amount of possible offshore fishing activity, responding accordingly. This relationship suggested that feeding on discarded fish and offal behind boats at sea was the birds’ preferred method, and that they chose to visit landfill sites only when fishing activity at sea was likely to be unproductive. In contrast, Herring Gull numbers at landfill sites were only marginally affected by strong winds and the birds tended to occur in similar numbers each day.

FIG 109. The numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls present at Coxhoe landfill site in County Durham between 11.00 and 12.00 on consecutive days. The site was closed on Sundays, and while some gulls still arrived then, they soon left, often without landing. The peak counts in both periods coincided with gale-force winds.

STUDIES ON MARKED INDIVIDUALS

In a study in north-east England, numbers of wintering Great Black-backed Gulls were captured at six landfill sites by cannon netting and each adult was given a unique combination of coloured rings that allowed them to be individually identified in the field (Coulson et al., 1984a). From the recoveries, various aspects of the birds’ behaviour and population dynamics were revealed.

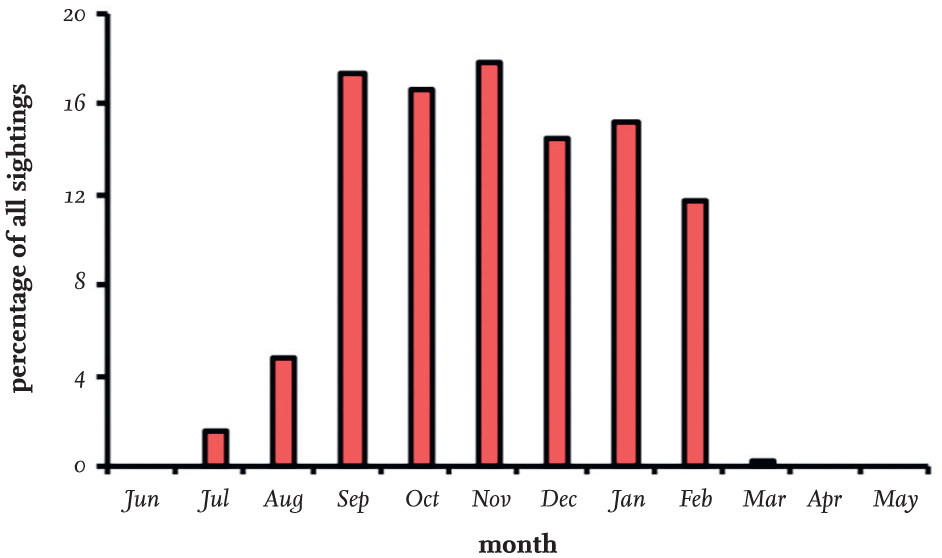

FIG 110. The percentage of all sightings in north-east England of colour-ringed adult Great Black-backed Gulls in each month (based on 461 field records), starting from June and following the winter during which they were marked. The majority of birds departed synchronously from the wintering area during the second half of February and the movement was virtually completed before March.

Breeding areas

Sightings and ringing recoveries of Great Black-backed Gulls in the breeding season identified their breeding areas. A total of 48 were reported from sites along the entire coastline of Norway and two were seen in north-west Russia, but only one was found breeding in Britain, in northern Scotland. From this, it appears that the great majority of wintering Great Black-backed Gulls in north-east England were migrants from Scandinavia and north-west Russia. All the adults visiting north-east England arrived in early September and left abruptly in the middle or end of February (Fig. 110), although a few immature individuals remained in some summers.

Visits to landfill sites

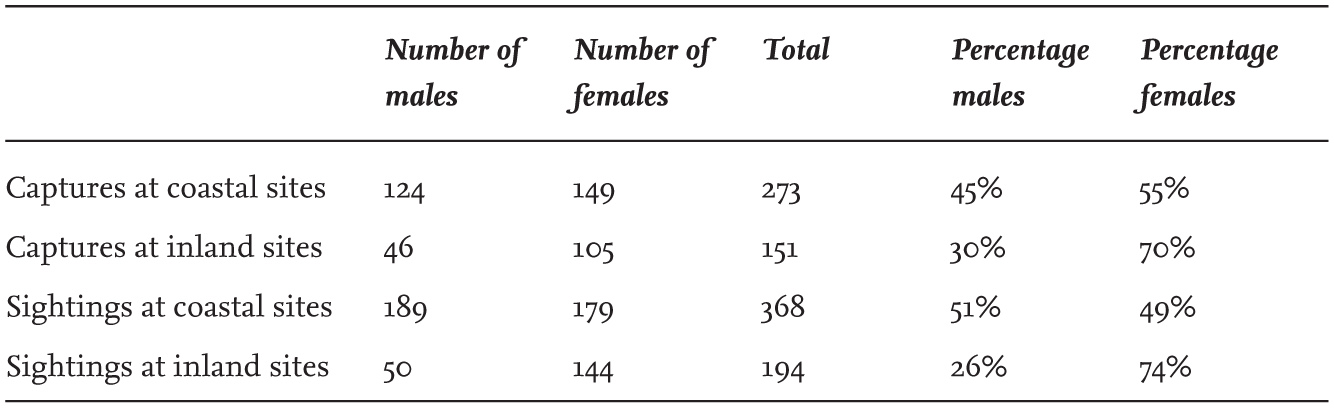

Great Black-backed Gulls visiting landfill sites near the coast were captured in almost equal proportions, but those caught at inland sites were dominated by females by more than two to one (Table 51). This difference in behaviour was confirmed by counts of the sex of unmarked birds, with females consistently more numerous than males at inland sites; subsequent sightings of the marked birds confirmed this finding. The reason for this difference in the behaviour of the sexes is not immediately evident, but it may indicate a greater preference of males to feed at sea.

In all, 424 Great Black-backed Gulls were captured at landfill sites in north-east England, and it was surprising that 81 per cent were full adults and only 8 per cent were in their first year of life (Table 52). Anne Hudson and Bob Furness found consistently high proportions of adults, averaging about 90 per cent, feeding behind fishing boats off northern Scotland. There are several possible explanations for these proportions. First-year (and older immature birds) may have been less inclined to move to north-east England from Norway, but there is no evidence of this. In any case, even smaller proportions of birds in their second, third and fourth winters were recorded, and so the habit of using different wintering areas would have had to persist for the first four years of life. Another possibility is that adults were more likely to be captured, but this explanation was rejected because field counts of unmarked birds at both landfills and coastal roosts invariably found that first-year birds formed less than 10 per cent of the Great Black-backed Gulls present. A third possibility is that the captures were representative of the population. If this was indeed the case, then the breeding success was low, with 80 adults (40 pairs) producing only eight young that survived to their first winter, equivalent to just 0.2–0.3 young fledged per pair each year. Great Black-backed Gulls in Britain often fledge more than one chick per pair and usually have a higher productivity than Herring Gulls breeding at the same sites. For example, between 1996 and 2015 on Skomer, Great Black-backed Gulls averaged 1.2 chicks fledged per pair and the figure fell below 1.0 in only three of these years. However, low productivity has been recorded by Clive Craik in western Scotland due to predation by American Mink (Neovison vison), while on Canna in the Hebrides, only 0.1–0.3 young were fledged per pair each year between 2001 and 2006, but then productivity improved to an average of more than one per pair between 2007 and 2015.

TABLE 51. The numbers and percentages of adult male and female Great Black-backed Gulls colour-ringed and then subsequently seen at coastal or inland landfill sites in north-east England.

TABLE 52. The age distribution of 424 Great Black-backed Gulls captured at landfill sites in north-east England, 1978–81.

Adult survival rates

A return rate of 82–84 per cent a year was obtained for adults using the same wintering area in north-east England (see below), suggesting that the survival rate would have been even higher had any marked adults been missed or changed their wintering area. The value above suggested that, unless numbers of Great Black-backed Gulls were declining, the adult survival rate must have been high. Urs Glutz von Blotzheim and Kurt Bauer suggested a 93 per cent annual adult survival rate for this species, and rates of between 78 per cent and 92 per cent were estimated recently at a colony in Newfoundland. An adult survival rate of 90 per cent was obtained for one year on Skokholm. There is a need for further estimates on the survival rates of this neglected species, but it is obviously long-lived. While the oldest ringed individual lived for just over 29 years in the wild, which is lower than the longevity records for most other species of large gulls, this could simply be because fewer Great Black-backed Gulls have been ringed, or that there is a lower viability of rings placed on this large bird and that some rings are lost before long-lived individuals die.

Winter site fidelity

Most of the colour-ringed adults marked in winter in north-east England returned to the same wintering site year after year and remained there throughout the whole season. Of the adults originally marked between September and November, 83 per cent were seen again in north-east England a year later, although surprisingly the return rate was lower for those initially captured and marked in December and January (Table 53). This lower rate suggests that some of these individuals may already have been moving north from more southern wintering areas when they were caught, although the main departure did not occur until mid-February (Fig. 110).

Of the adults that were seen in the following winter, 80 per cent were found at the sites where they had been initially ringed, suggesting that they benefited from experience and knowledge of food sources in their chosen wintering areas. Of the 20 per cent of individuals that were seen, but at a site other than that at which they had been ringed, none had moved further than 30 km.

TABLE 53. The proportion of Great Black-backed Gulls colour-ringed in north-east England and seen there in a subsequent winter.

This behaviour contrasted with that of the 34 birds that were in their first year when marked. None was seen again in northeast England in a subsequent winter, and presumably the majority had moved to winter in other areas, although some would have died. Some of those marked in their second or third years of life returned, but they did so at a much lower rate than full adults. The return of some adults to the same wintering area has been recorded in several gull species, but most of these records were of a specific individual. Where overall rates of return do exist for other species, they show much lower rates than reported here for the Great Black-backed Gull.