Chapter 4

Illness, death, and the demographic impact

Prior to the introduction of ART, an HIV infection led to illness and eventual death. The consequences of AIDS stem from this increased morbidity and mortality. Treatment means that if a person is able to access the drugs and is adherent, illness and death can be avoided, or at least postponed. In the case of infants, whose infection stems from vertical transmission, prevention is straightforward provided they and their mothers are reached.

Demography and the epidemic

Demography is the study of population dynamics. It collects data on quantifiable events for analysis and projection. The basic data sources are censuses, civil registration, collection of vital statistics, in some countries demographic and health surveys (DHSs), and household surveys. Most censuses are undertaken every ten years, so other data sources are invaluable, especially since the release of census data may take years. Demographers and planners want to know, at a minimum, the number of births, fertility and death rates, and migration patterns.

An increasingly important source of information is civil registration, defined by the United Nations as the ‘Universal, continuous, permanent and compulsory recording of vital events’. This recording of milestones including birth, marriage, divorce, adoption, and death is a government responsibility. The process provides individuals with documents to secure recognition of their identity, family relationships, nationality, social protection, and inheritance. It facilitates access to essential services: health, education, and welfare; is important for political engagement (voting); and economic activity (bank accounts and employment).

Vital statistics and the ability to monitor and respond to causes of death and disability underpin national and international targets, including the sustainable development goals (SDGs), universal health coverage, and tackling epidemics. In South Africa birth registrations rose from fewer than 25 per cent in 1991 to over 90 per cent in 2012. Similar improvements have been recorded in death registration, which is compulsory before legal burial or cremation. It allowed deaths to be tracked and AIDS impact inferred.

Demographic consequences of AIDS may include: increased deaths especially among adults; rising infant and child mortality; falling life expectancy; changes in the population size, growth, and structure; and growing numbers of orphans. How serious these impacts are depends on the location, size, and age of the epidemic; the underlying demographics of a country; and, increasingly, the availability and uptake of treatment.

Increased mortality in adults

In the USA, prior to ART, AIDS was the leading cause of mortality for young men, killing some 21,000 in 1995. In 2013 AIDS was ranked as the seventh most important cause of mortality for males in this age group, accounting for 8,324 deaths. The African American community bears a disproportionate burden with 6,540 deaths.

In most countries the number of deaths has peaked. In Uganda the highest level of mortality was in the 1990s. As a result many children were orphaned. While grandparents (especially grandmothers), older siblings, and the community generally ensured these children had some support, most were materially deprived and all bear emotional scars. They are the young adults and, increasingly, the parents of today.

The increase in deaths was the most visible and measurable effect of AIDS. In Southern Africa, prevalence rates rose rapidly from 1992, and in the early part of the new millennium there was a quantifiable and significant rise in deaths. This was dramatically illustrated by data from South Africa’s vital registration system. In 2001 the Medical Research Council released a report analysing registered deaths. It showed mortality had shifted from the old to the young, particularly to young women, and there was differential mortality by gender. The future burden of the epidemic was predictable in terms of deaths if treatment was not made available, and in numbers needing treatment if it was.

This was the time South Africa was entering its ‘denial period’. President Thabo Mbeki argued, confusedly, that HIV did not exist, but if it did then it was not a killer virus. He was backed by Minister of Health Manto Tsabalala-Msimang, who became known as Dr Beetroot for her advocacy that people eat garlic, beetroot, and lemon to stay healthy. The attitudes were greeted with disbelief by most scientists and health professionals, and some senior government and political figures. It was partly resolved when Mbeki announced he was withdrawing from the discussion, and from 2004 the public health service in South Africa began rolling out ART. University of Cape Town economist Nicoli Nattrass estimated there were more than 340,000 unnecessary AIDS deaths between 1999 and 2007 as a result of this policy.

The changing mortality is shown in Figure 6. Deaths among women aged 30 to 34 more than quadrupled between 1997 and 2005, from 7,196 to 31,283, and then fell to just under 14,000 in 2013. Among men the peak in mortality was slightly later, but with the same change in the pattern and numbers. The cause of death is not ascribed in the data: the graphs simply show numbers. However, caeteris paribus, it is clear AIDS mortality and subsequent availability of treatment is at the root of changing configurations.

6. Total registered deaths by age and year of death, South Africa.

The earliest and gloomiest projections of the likely effects of AIDS came from the US Bureau of the Census. Their 2004 report, ‘The AIDS Pandemic in the 21st Century’, produced country data ‘with AIDS’ and ‘without AIDS’. The figures were bleak. In Botswana, in 2002, the crude death rate (CDR)—the deaths per 1,000 people—was estimated at 28.6, without AIDS it could have been a mere 4.8. Data from the WHO Global Health Observatory gives Botswana’s 2013 CDR as 7.2. For Tanzania the 2002 figures were: without AIDS 12.1, with AIDS 17.3; the 2013 figure is 7.8. The top CDR in a high prevalence country is Lesotho’s 14.1 in 2013.

Infant and child mortality

Infant and child mortality rose, due partly to vertical transmission. Intervention can eliminate this: it is rare for infants in the developed world to be born with or acquire HIV infection. In some of the poor world preventing vertical transmission remains challenging. In 2014, globally 220,000 children were newly infected, however UNAIDS says in twenty-one priority African countries 77 per cent of pregnant women received ART, and the number of infant infections fell by 48 per cent between 2009 and 2014. The 2014 Swaziland Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (SMICS) found 95.3 per cent of women reporting a live birth in the last two years were offered and accepted an HIV test, and received the results.

Infected infants have poor life expectancy. In the developed world 70 per cent of those infected at birth are alive at 6 years and 50 per cent at 9 years. In the poor world progression rates are faster. About 25 per cent of HIV infected babies develop symptoms of AIDS or die within the first year. Treating children is a growing global priority but drug development lags, perhaps because transmission can be eliminated and there are not the same profits to be made from paediatric medicines.

The second reason for increased under-5 mortality is deaths among infected mothers. Losing a mother for any reason has an adverse impact on child survival. A 2004 review of the demographic and socio-economic impact of AIDS in the journal AIDS noted that the death of a mother increased the chance of a child dying by three times in the year before the mother’s death, and by five times in the year after it. Increased child mortality was not affected by the mother’s cause of death, but HIV-infected mothers are much more likely to die.

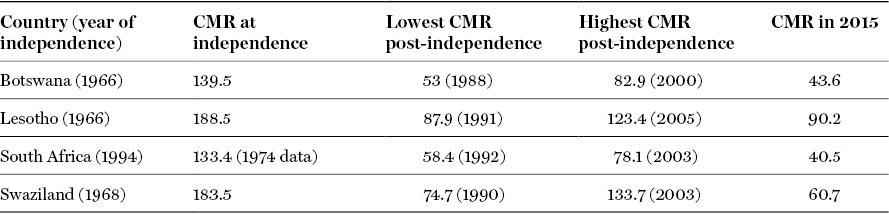

The child mortality rate (CMR), which is the death of a child between 1 and 5, illustrates both the impact of the disease and the roll-out of treatment. The World Bank database provides figures as shown in Table 4. It can be seen that CMR falls with development, rises with the arrival of the epidemic, and then falls again as treatment becomes available.

Table 4 Changing child mortality rates in selected countries

The World Bank: Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT

Falling life expectancy

The effect of AIDS on life expectancy was dramatic in Southern and Eastern Africa. There was a small impact in Thailand and it was negligible elsewhere.

Data for selected African countries are shown in Figure 7. The first country to track a fall in life expectancy was Uganda in the mid-1980s, albeit from a low level. The shocking lack of improvement in life expectancy in the post-independence period was due to the coup that brought dictator Idi Amin to power in 1971; the seven-year political turmoil that followed his overthrow in 1979, up to 1986; and the subsequent war when current president Yoweri Museveni swept to power, bringing stability to Uganda. This political and economic mayhem contributed to the spread of HIV and AIDS, and continued to erode life expectancy in the early years of Museveni’s rule. However he was also the first African leader to respond to the epidemic: life expectancy was turned around and continues to rise.

7. Life expectancy.

Botswana’s life expectancy was age 52 at independence in 1966; after twenty-five years of stable political rule and steady economic growth it was 63. In 1991, AIDS mortality began climbing. By 2006, forty years after independence, life expectancy was just 46, although it is recovering. The lowest life expectancy recorded in a high prevalence country was age 43 in 2001 in Zimbabwe. Obviously the political and economic turmoil under the malevolent rule of Robert Mugabe contributed to this. The graph shows Zimbabwe to be an outlier since life expectancy is almost back to the pre-AIDS level, a possible example of dubious data.

The data do not show what this catastrophic decline in life expectancy actually means. Did it affect societal ability to function? This issue is returned to, but it is worth stressing that we do not know, partly because impacts are still evolving; demographers don’t think in these terms; and most other social scientists are not engaged.

Changing population composition

Increased numbers of deaths reduce population growth and size. Some 1.2 million, mostly young adults, died from AIDS in 2014. In the worst-affected countries the mortality is still considerable: Statistics South Africa reports that in 2014 there were 171,733 AIDS deaths in South Africa, down from a peak of 363,910 recorded in 2005; UNAIDS data record 170,000 deaths in Nigeria in 2014, up from 130,000 in 2000. Outside Africa the greatest mortality is in Indonesia where 34,000 people died in 2014; in 2000 there were fewer than 1,000 deaths. In Thailand the number of deaths fell from 54,000 to 19,000 over the same period. Ukraine saw deaths increase from 6,300 to 15,000.

Population growth decreases due to premature death, reduced fertility, and changing sexual behaviours. As the epidemic progresses there are fewer women of childbearing age. HIV+ women are less likely to conceive and carry the infant to term, thus further reducing the number of live births. Behaviour change has significant potential effects. Condoms now used to protect against disease also have an impact on fertility. A higher age of sexual debut will reduce the total fertility rate.

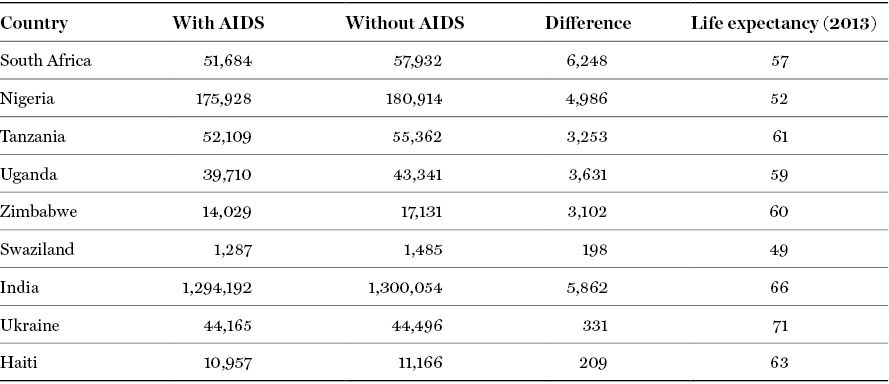

In most countries AIDS simply means the population will grow more slowly. In India and China the impact is small as the populations are so large and the epidemic relatively insignificant. The UN estimated that in China, in 2015, the population was only 0.16 per cent lower due to AIDS. In Southern and parts of Eastern Africa AIDS has, according to UN data, lead to smaller populations—as shown in Table 5—with consequent potential impacts for economies and social services.

Table 5 Populations in 2015 with and without AIDS (in thousands)

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2010). Population and HIV/AIDS: 2010. Wall chart (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.10.XIII.9)

In Eastern Europe, AIDS exacerbates troubling economic and demographic situations, with very low fertility rates and declining populations. Births in Russia in November 2014 were down by more than 5 per cent year-on-year, and immigration decreased by more than 10 per cent. Between 1993 and 2015, Russia’s population decreased from about 149 to 144 million people. Based on the present trends there could be between 100 and 107 million in 2050. Russia had between 850,000 and 1,300,000 people aged over 15 living with AIDS in 2013. Mortality among the 15- to 30-year-old age group is increasing, and slow treatment roll-out worsens this.

Population pyramids are shown in Figure 8. The first bleak one produced in 2004 by the US Bureau of the Census is the projected impact for Botswana in 2020. The outer bars show the shape and size of the population in the absence of AIDS. While the gaps in the under-25 age group are a combination of mortality and births that did not occur, among the over-25 age group the change is due to deaths. The second is from 2014. It is clear changing behaviour and the roll-out of ART had a huge effect, although increased mortality can be seen in the 40- to 70-year-old cohorts.

8. Botswana population pyramid with and without AIDS, and 2014 actual.

The dependency ratio is an age–population ratio of those not in the labour force (the dependent part including children, people in education, and over-retirement age) and those of working age (the productive part). Conventional dependency ratio calculations assume most adults are productive. In generalized AIDS epidemics, where there is no treatment, significant numbers may be chronically sick and properly belong in the ‘dependents’ category.

The availability of treatment means social and demographic consequences can be postponed as long as drugs are available and people take them. Providing treatment means population pyramids and dependency ratios won’t see the dramatic changes predicted fifteen years ago. Of course, in most of the resource-poor world, the cost of drugs puts them beyond the reach of individuals. They are provided by governments, NGOs, or faith-based organizations. Most funds come from national budgets and/or donors. It is evident therefore that there is a new dependency, of individuals on those who deliver the treatment, and of some nations on international agencies and philanthropic governments.

There may be changes in the gender balance. In heterosexually driven epidemics more women than men are infected and at younger ages. This may influence men to seek sexual relationships with younger and younger women, potentially increasing HIV infection rates. On the other hand, evidence suggests that women are more likely to seek care and therefore get treatment. Where AIDS mortality is high families are held together by the elderly, usually grandmothers.

Orphaning

In classic terms, an orphan is a child who has lost both parents. The definition of ‘an orphan’ has changed, in large part due to AIDS. The current definition used by UNICEF, other international agencies, and most NGOs for an orphan, is a child under the age of 18, who has lost one or both parents. Maternal orphans have lost a mother, paternal orphans a father, and double orphans both parents.

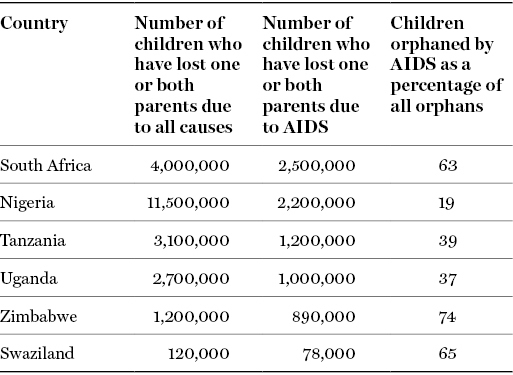

Globally, in 2012, there were an estimated 150 million orphans, 17.8 million due to AIDS. In sub-Saharan Africa there were fifty-six million orphans of whom 15.1 million were AIDS orphans. Table 6 shows the countries with the largest numbers of AIDS orphans. There are no country data outside Africa.

Table 6 Orphaning in selected African countries

Sources: South Africa (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR206/FR206.pdf); Nigeria (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR293/FR293.pdf); Tanzania (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR243/FR243%5B24June2011%5D.pdf); Uganda (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR264/FR264.pdf); Zimbabwe (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR254/FR254.pdf); Swaziland (http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR202/FR202.pdf)

There are limits to demography. AIDS orphans have different experiences and bear additional burdens compared to those orphaned by other causes. AIDS deaths are protracted. Children who have lost one parent to AIDS risk losing the other, since unprotected heterosexual sex is the major HIV transmission route.

There is an emotional impact which goes uncounted. These children experience many negative changes and can suffer neglect, including emotional abandonment, long before they are orphaned. Death of a parent results in trauma, but AIDS deaths leads to higher levels of psychological distress. Anxiety, depression, and anger are more common among AIDS orphans: 12 per cent of AIDS orphans said ‘they wished they were dead’: among other orphans the figure was 3 per cent.

Children separated from their siblings can face psychological problems. A 2002 survey in Zambia found more than half of orphans no longer lived with all of their siblings. In Lusaka in 2005, I heard the story of how a grandmother and her sister had taken in two grandchildren, boys aged 9 and 13, when their mother died. Both went to homes with an income, care, and love. One child was taken to the north, the Copperbelt, the other to Livingstone in the south. The women remarked the boys really missed each other and were overjoyed to see each other on the infrequent occasions they met.

Losing a parent to AIDS can have serious consequences for a child’s access to basic necessities and education. Orphans are more likely than non-orphans to live in large, female-headed households where more people are dependent on fewer income earners, or with grandparents where there may be no income at all. In her seminal book on HIV and East Africa, reflecting on thirty years of the epidemic, Janet Seeley shows how all too often it is grandparents who bear the burden, usually without support or thanks.

May Chazan’s ethnographic study of grandmothers in KwaZulu-Natal has similar findings. Chazan specifically asked Southern African grandmothers why they continued to care for children who they felt were abusive and not committed to their families. One replied, ‘We stay here because we love our families, we love the children, and it is our job to raise them’. It is tragic for children to lose parents and tough for the elderly to have to take on unexpected burdens when they are poor and often in ill health. Extended families may absorb orphans, but their capacity and capability is limited.

Children grieving for dying or dead parents may be stigmatized by society through association with AIDS, which leads to shame, fear, and rejection. They may be denied access to schooling and health care because it is assumed that they are infected. Realization of the potential effect of AIDS led to much research, and to many NGOs and especially UNICEF taking steps to proactively address this.

Under my directorship, the Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division (HEARD) carried out two major studies on children affected by illness. The Amajuba Child Health and Wellbeing Research Project conducted in KwaZulu-Natal between 2003 and 2007 found differences between orphan and non-orphan caregivers; the former being more likely to care for more children, have poorer health, experience higher levels of chronic illness, receive less adult help, and bear more daily responsibilities. More orphan caregivers said children in their care needed help for mental or behavioural issues. However only 3.4 per cent of households had contact with child welfare agencies. The second study, with Oxford University in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, examined the impact of living in an AIDS-affected family on the health of children; unsurprisingly it was worse. It found 49 per cent of the caregivers sampled experienced anxiety—considerably higher than the 16 per cent estimated nationally.

Beyond demographics to social and economic impact

At the root of the difficulties in understanding the effects of the epidemic is what we measure, and when and how we measure it. Demography looks at events. An AIDS death is an event. The preceding period of illness is prolonged and debilitating for the individual, and costly and demoralizing for families, households, and communities, but is part of a process and not measured by demographers. The studies carried out by HEARD, Seeley, and others show people cope because there is no other option.

Impacts continue to be felt by families and communities after death. There is evidence that AIDS deaths have more serious consequences for survivors than deaths from other causes. The ‘post-death’ consequences are not measured by demography. This needs examination by other disciplines. Our work on orphans measured the impact of AIDS; we did less well in changing policy to support children.

The advent of mass treatment has been a game changer. It means deaths can be averted, but at a cost. While the demographic impact may be reduced, the ideas of dependency and dependency rates needs to be reconsidered. People and nations are experiencing a new dependency on the largess of those who provide treatment.