CHAPTER 1

FOSTERING A HELPFUL PERSPECTIVE

Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.

—Henry Ford

You’ve bought the book, you’re ready to tackle items on your to-do list, and you’re feeling more motivated than you can ever remember. Your impulse is to take off and initiate movement toward your goals while you’re feeling hot—but WAIT! Do not “pass go” before thoughtfully reading the following chapter, or you might sabotage your efforts.

Take a moment and think back to all the times you tried out a new strategy someone told you about or that you read about in an article on, say, staying organized. If you’re like most adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), it is likely that the strategy was helpful for a short period of time, only to be forgotten or cast off when it “no longer worked.” What if I told you that the strategy actually worked just fine and what, in fact, didn’t work was what you told yourself about it the moment you began to lose interest or the first time you forgot to implement it? Chances are you didn’t speak to yourself in a very user-friendly way but, instead, came down fairly hard on yourself, criticizing your lack of follow-through or ability to get things done due to “learned helplessness” (the perception that because you failed in the past, you will always fail). By doing so, you create a self-fulfilling prophecy on repeat, trying and getting stuck, thinking thoughts that make you feel hopeless or helpless, and then giving up. The good news is that this cycle can be unlearned. And it starts with changing the way you think.

Not convinced your thoughts have such power over your actions? Take the following quiz to see if the ideas in this chapter apply to you. The more “yes” answers you give, the more helpful this chapter will be to you.

QUIZ YOURSELF—DOES THIS SOUND LIKE YOU?

- Have you tried many strategies over the years to address your ADHD symptoms, only to end up casting them off as unhelpful because they only helped for a few days or months?

- Do you often shy away from setting goals or trying a new strategy because you “know” it won’t work out in the end?

- Do you find yourself getting angry or upset when things don’t go exactly as you had hoped or planned?

- Have you jumped from one strategy to the next over the years in search of that one that will work (every time, for all time) for you and still not found it?

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

Every day, all of us encounter and engage in hundreds, if not thousands, of events, small and large. And, every day, we have a choice as to how we are going to interpret each of those events. How we choose to think about these events impacts whether we feel positively or negatively toward ourselves and others.

For example, suppose you buy a new planner designed for adults with ADHD and use it regularly for 3 months. You then lose it under a pile of books, only to forget about it the next day and stop tracking your appointments. Five weeks later, you find it. At this point, you have many options for what and how to think about this event. A common response from an adult with ADHD with learned helplessness might be, “Here I go again. Another wasted planner to add to the pile. What the hell is my problem?” However, a more adaptive and helpful response might be, “Wow, I used that planner for 3 months! While it wasn’t helpful forever, that’s a good bit of time, and I definitely want to stow that somewhere so I can possibly make use of it again down the road when it feels new again!”

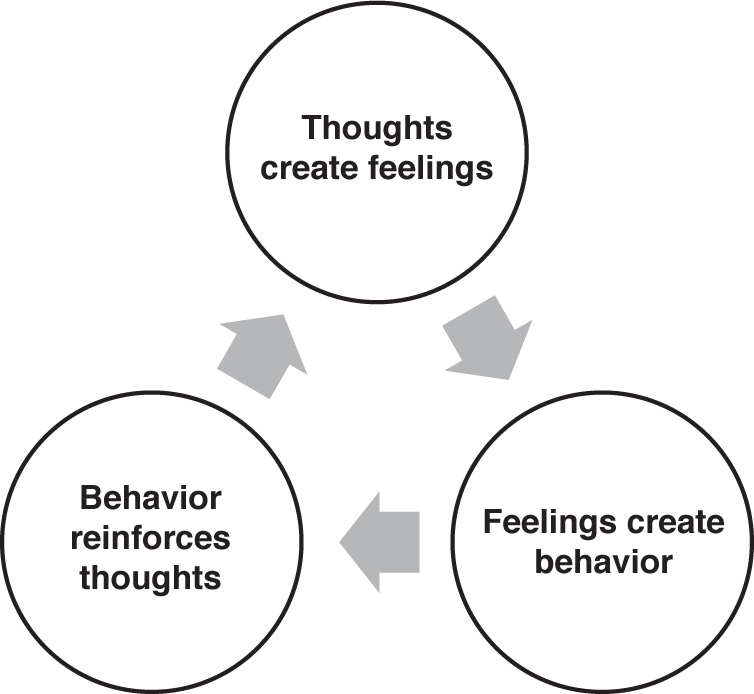

How do you think you would feel about yourself if you had thought the first way? How would you behave? Chances are you would have felt defeated and given up. Yet, had you thought the second way, seeing the “good” in the situation, you would have likely felt encouraged and excited about what you achieved. Thoughts create feelings, feelings create behavior, and behavior reinforces thoughts. This is the basis of two reigning psychological theories: cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and positive psychology (Nimmo-Smith et al., 2020). CBT is highly effective for adults struggling with ADHD and mood disorders (most often, anxiety and depression), which is estimated to be over 80% of adults with ADHD (more on the topic of comorbid disorders in Chapter 9). While the remaining 20% may not reach criteria for a mood disorder, negative thinking patterns can still get in the way of progress. All adults with ADHD can benefit from these lessons in CBT.

Cycle of Thoughts, Feelings, and Actions

Positive psychology aims to uncover what allows individuals to thrive—achieving their personal and professional goals and cultivating happiness, resilience, and meaning in life (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2015). Positive emotion is fundamental to both theories, and it is achieved through rational and positive thought. One of the most important insights we have gained from positive psychology is that individuals are not happy because they reach their goals. Rather, happiness causes individuals to reach their goals. In other words, you don’t feel hopeless because you can’t keep your house organized. You can’t keep your house organized because you feel hopeless.

WHAT ARE THINKING ERRORS?

Thinking errors, also known in the field as cognitive distortions, are the faulty connections we create between thoughts, ideas, actions, and consequences without adequate evidence, which then influence our feelings. While psychologists have long understood the impact of these distortions on our mood, the importance of addressing such thoughts has only gained momentum in recent years (Strohmeier et al., 2016). David Burns, MD, a prominent positive psychiatrist and author of Feeling Good and Feeling Great, does a stellar job of explaining how overcoming thinking errors can vastly improve symptoms for depression and anxiety, but how does it help adults with ADHD?

First, let’s identify the six thinking errors most common in adults with ADHD, followed by an example of each.

- Ignoring the Good occurs when you give more attention to the things that are going wrong or are negative about a given situation rather than what is right or going well. Burns (1999) referred to this as a distorted “mental filter.”

Adult ADHD Example: You were 5 minutes late to your appointment, and all afternoon you beat up on yourself for once again not making it somewhere on time. - Catastrophizing or Blowing Things Up occurs when you make a really big deal out of something that should have a relatively small impact on your well-being.

Adult ADHD Example: You forgot to take out the trash after promising your partner that you would, and you tell yourself you are unreliable and can’t be trusted to do anything right. - Fortune Telling occurs when you think that you already know the outcome of a situation and that it will not be positive.

Adult ADHD Example: Your professor or boss assigns a project, and, before knowing all the details, you assume it’s too difficult for you and that you will fail to produce something good. - Mind Reading or Jumping to Conclusions occurs when you think you know what someone else is thinking or what their intentions are without them ever verbalizing.

Adult ADHD Example: Your neighbor pops by your messy house, and you assume they are thinking what a lazy slob you are. - All-or-Nothing or Black-and-White Thinking occurs when you don’t achieve something 100%, so you think you have failed. You filter everything in extremes without seeing the metaphorical shades of gray.

Adult ADHD Example: You attempt a new recipe to cook dinner for your family, and, because you forgot to include one ingredient, you think dinner is ruined. - Emotional Reasoning occurs when you believe something to be true simply because you feel it to be true, sometimes even in the face of contradictory evidence.

Adult ADHD Example: You think everyone in your office gets 3 times as much work done as you in a day because you feel so unproductive.

Use Exhibit 1.1 to record which thinking errors you find yourself committing, and include an example of each.

EXHIBIT 1.1. Try It! Identifying Thinking Errors

Thinking error |

Is this me? (check if so) |

Example of when and how I engaged in this thinking error (try to be as recent and specific as possible) |

|---|---|---|

Ignoring the Good |

||

Catastrophic Thinking |

||

Fortune Telling |

||

Jumping to Conclusions |

||

All-or-Nothing Thinking |

||

Emotional Reasoning |

GETTING BACK ON TRACK: CORRECTIONS IN THINKING

Now that you have gained some awareness and insight into your destructive thought patterns, it’s important that you learn how to challenge or “reframe” them. Remember, positive thoughts lead to positive feelings. Positive feelings lead to positive behavior (i.e., goal achievement). I can all but guarantee that you will fail to exactly meet one or more objective you set for yourself in the coming weeks, even with the help of this book. And here’s a little secret: Even people without ADHD fail once in a while. What is ultimately most important in achieving success with your goals is arming yourself with the ability to accurately and positively reframe a situation when things don’t go as planned. Imagine you are driving in your car and come across a roadblock between yourself and your destination. Think of it as an inconvenient speed bump, and you’ll likely look for an alternative route. Think of it as a dead end, and the chances are good you will give up and go home. As an adult with ADHD, you are likely to hit more “speed bumps” than a neurotypical adult. This just means you need to be extra good at reframing in those moments.

If admitting you have a thinking problem is the first step, learning how to reframe these thoughts is step two. Let’s take what you have learned from CBT and positive psychology and create more accurate, alternative thoughts for each of our thinking error examples. First, recall that a thinking error often leads to a negative or irrational thought. Next, reflect and reframe the irrational thought to eliminate the thinking error.

Now, let’s practice reframing. Here are some examples.

Example 1:

- Event: You are 5 minutes late to an appointment.

- Original Thought: Once again, I am late! Why can’t I get anywhere on time?!

- Thinking Error: Ignoring the Good.

- Alternative or Reframed Thought: Last time, I was 15 minutes late to this appointment, so I am improving. The time before that, I forgot it altogether! I also remembered all of the things I needed to bring and got here safely. I called on my way in to let them know I would be late, and they said it was fine and not to rush because they know me and value my contribution. So, really, lots of good things are happening, and being late was just a tiny hiccup in my day.

Example 2:

- Event: You forgot to take the trash out after promising your partner that you would.

- Original Thought: I am so unreliable! I can’t do anything right!

- Thinking Error: Catastrophizing.

- Alternative or Reframed Thought: That’s the first time I’ve forgotten this month. That means I got it right three times, and this is just a slipup. There is a lot of evidence from my life that shows I am reliable—I pick up the kids from school every day, get my work done, pay my bills on time, and I’ve remembered to take my meds all week. Plus, so what if the trash stays in the garbage bin for another week? Life will go on just fine.

Example 3:

- Event: Your college professor assigns a project.

- Original Thought: There’s no way I can do this. I have no idea where to start and will probably fail anyway, so why bother?

- Thinking Error: Fortune Telling.

- Alternative or Reframed Thought: I haven’t even looked at the assignment. I may struggle in this class, but this project may be an opportunity for me to bring my grade up. I do well when I break things up into small steps, and I’ve been successful on projects in the past. I’ll set up an appointment with the professor to see if they can give me any guidance—something I haven’t tried before. What else can I do to put supports in place so that I can succeed?

Example 4:

- Event: Your neighbor invites themselves into your messy house.

- Original Thought: They must think I am such a lazy slob. I am so embarrassed. No way are they going to want to hang out with me after this. I’ll probably get a reputation around the neighborhood as a hoarder or something.

- Thinking Error: Mind Reading.

- Alternative or Reframed Thought: Yes, the house is messy, but I don’t know what they are thinking. They haven’t commented on the mess and are continuing to smile and speak to me. I have just as much evidence to think they’re glad they’re not the only one with a messy house! Or maybe they are just glad to be here. Bottom line, I don’t know what they are thinking and shouldn’t assume I do. I’ll just enjoy the company.

Example 5:

- Event: You attempt a new recipe to cook dinner for your family and forgot to include one ingredient.

- Original Thought: Dinner is ruined! This day is terrible!

- Thinking Error: All-or-Nothing Thinking.

- Alternative or Reframed Thought: Dinner might not taste perfect, but I’m grateful to be sharing a warm meal with my family. I’m also proud of myself for trying something new! I wouldn’t expect myself to be perfect the first time I take on a new sport, so why would I expect it in this situation? And, really, the rest of my day has gone well. If messing up dinner is the worst thing that’s happened to me today, I’ll take it.

Using your personalized examples of thinking errors from Exhibit 1.1, create an alternative, evidence-based statement in Exhibit 1.2. Want to take it a step further? Write in how this new thought makes you feel and what action you would take (if any) as a result.

EXHIBIT 1.2. Try it! Reframing Cognitive Distortions

Original thought |

Alternative thought |

New feeling |

New behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

SUMMARY

Here are the important points you will want to take away from this chapter. Use the following checklist to note the areas you have thoroughly studied. Leave the box empty if it is an area you would like to come back to and review further.

- I understand how “learned helplessness” affects adults with ADHD.

- I have learned how my thoughts impact my behavioral outcomes.

- I have identified the thinking errors I must watch out for.

- I know how to reframe my negative or irrational beliefs into more helpful and accurate thoughts.