6

In workshop, a couple of buildings north, Jo was wrapping up. Her bit was called “The Year After, at Marienbad” (she insisted on titling her work, though Kruger kept saying it wasn’t necessary), and no one got it. Instead of listening quietly to the critique that followed, like she was supposed to, Jo tried to explain herself by showing the class long clips of the movie Last Year at Marienbad, which she’d drawn inspiration from. For a minute, it wasn’t clear whether this was still part of the bit, so Kruger let her do it.

“The movie itself is hilarious because it’s so pretentious,” Jo said. “All the characters are so stiff and self-important, and the plot makes zero sense because we never know if they’re lying or telling the truth or dreaming or remembering.”

“Sounds like shit,” Dan said.

“And so, since the mystery at the center of the movie is never explained,” Jo went on, “I thought I could run with the idea that every year something weird and unexplained happens in Marienbad, and I imagined that the weirdest thing that could happen to that specific cast of characters would be for them to suddenly acquire a sense of humor.”

“Okay,” Phil said encouragingly. “I see. That wasn’t super clear in your bit.”

“Of course it wasn’t,” Kruger said, ready to assume now that Jo’s performance was over. “You can’t rely on your audience having seen a French movie from the sixties in order for your jokes to land.”

“Even Breathless?” Jo asked.

“Let’s see,” Kruger said. “Who in this room has seen Breathless?”

Of all six students, only Marianne raised her hand, but Marianne didn’t count, because she was—like Godard himself, she reminded everyone—Swiss.

“I see your point,” Jo said, and she went back to her seat.

Artie was up next. He clipped the blown-up picture of himself to a paperboard easel he’d never seen anyone use.

“I know what you’re thinking,” he started. “You’re thinking, This guy is too good-looking to be funny.”

Kruger stopped him right away.

“Don’t tell the audience something they already noticed.”

Kruger usually let the students go uninterrupted, even when they were bombing hard, but his father was on his mind, and his father always said that teaching was adapting to the class you were given: if something wasn’t working, if your students weren’t learning, you had to change things up.

Artie was confused.

“Should I go on anyway?” he asked. “Or should I try to find a better opening line?”

“Don’t tell the audience something they already noticed,” Kruger repeated, and Artie said he thought it was kind of the principle of comedy, actually, to find common ground with the audience, to point out stuff they’d already noticed but hadn’t perhaps quite realized yet that they’d noticed.

“No one cares that you’re pretty,” Kruger insisted. “No one wants to think about pretty at a comedy club. If they’re thinking about your looks too much, then they’ll start thinking about their looks, and they’ll be self-conscious, and they won’t laugh, because everyone’s ugly when they laugh.”

Artie wasn’t sure he agreed with that, but the whole class nodded, and he let it go.

“Okay,” he said. “But the entirety of the bit is kind of about my looks, so what should I do?”

“Do something else,” Kruger said. “Improvise. Crowd work. Anything.”

Artie had never done well in improv. They had improv with Dorothy once a week, and he’d skipped two of those classes already, made up fevers. He’d faked hoarseness once, too, thinking this would allow him to sit in class and quietly watch the others perform—a way to be absent while still showing up—but it had backfired when Dorothy said improv was finding ways around your weaknesses and spent the better part of two hours trying to squeeze a bit of decent physical comedy out of him.

“I don’t know,” Artie said to Kruger. “I’ve got nothing.”

“You’re not allowed those words in our line of work,” Kruger said.

Which Artie knew, of course. The way around writer’s block was to write about writer’s block until something interesting came up. It was one of the first lessons imparted on them here. Take note of everything you see that gives you the slightest brain jolt. No need to form a full thought about it right away, much less a joke, but to take note was important. If it was anything worth pursuing, it would keep working within you. You could never be empty if you took notes all the time.

Artie had been keeping a notebook since he was a teenager, but he’d always been ashamed about it. Part of him believed you were a bad writer if you needed one, laborious. His parents had never seen it, for example. Not that they knew much about writing, but the notebook would’ve made them self-conscious, Artie thought, and wonder what their son was seeing at the dinner table that they weren’t. It felt particularly wrong showing up with a pen anyplace his father was. The man was so intent on making little out of things, on never riffing, on noticing only the bare minimum for survival (where the water pitcher was, the emergency exits), that he might not have even seen the notebook if Artie had set it on the table, but his wife would’ve brought it to his attention, and he would’ve said something like “What’s there to write about us, son? We’re not interesting,” after which Artie would’ve been forced to agree, or worse, to listen to his mother’s follow-up, her attempts at convincing her husband and children that that was nonsense, that there was in fact a lot to say about their family, and then after that serve them, as illustration, one of the two anecdotes she liked reliving (the time they’d been robbed by highway police in Mexico on their honeymoon, the time Mickey had won first place in the regional chess tournament and met the governor—two anecdotes in which Artie didn’t appear).

Artie thought back on the notes he’d taken so far today. At breakfast, he’d written something about ex-girlfriends showing up in dreams as if you’d never broken up with them (the big talk still to be had), and the relief it was after a dream like that to wake up alone in bed in the morning. He wondered if that was a universal dream, a universal feeling. After his phone call with his mother, he’d noted: “addicted = positive.” Right before the start of class, he’d written down that scene he’d imagined with the tech company idiots. It might not be the most promising bit to pursue, but in this moment, it was the clearest in his mind.

“My phone wants to bond with me,” Artie started. “It really wants us to be friends.”

Olivia was smiling already. Because he was funny? Because she could tell he was driving into a concrete wall? Artie wondered if he should take his phone out of his pocket for illustrative purposes, elected not to.

“I was walking around earlier,” he went on, “minding my own business, and it just texted me. It used to be people texted you, now it’s your own phone checking in.”

Mild chuckles—not from Olivia, not from Kruger.

Artie mimed the act of holding a phone, not to his ear (no one did that anymore) but at chest level, eyes looking down into it.

“I thought, you know, if my phone wants to tell me something, it has to be important, right? Like there’s a terrorist attack in the neighborhood, or some kid is being raped nearby.”

He shouldn’t have said “raped,” he thought.

“But you know what the dumb phone wanted? It wanted to see if I remembered a fishing trip I took five years ago, with my grandfather.”

Why say a fishing trip? He’d never been fishing in his life.

“ ‘On this day five years ago,’ it said, with a big stupid selfie of my grandpa and me. What a weirdo. The phone, I mean, not my grandpa. Why remind me of that day, of all the days we’ve had together since I bought it? Was it a particularly meaningful fishing trip for my phone? And I didn’t realize it? Why is it so important that I remember the fishing trip now, right this moment?”

No laughter.

“This phone, it’s like having a girlfriend, really. I feel like there’s more coming, like I can get quizzed about our life together at any point. Do I remember our first night? When I plugged it in by the bed, protective plastic still unpeeled?”

The phone-as-girlfriend shtick wasn’t working, wouldn’t work. Artie needed to change course.

“Worst part is,” he said, “my grandpa died a couple years back.”

God. Why? What was he doing? Why wasn’t Kruger stopping him now? Quick, come up with a funny death.

“Nothing extraordinary. He just ‘had a fall,’ as they say, and he died. I didn’t take a photo of it, though, of my grandfather falling, so I guess my phone just doesn’t know it happened.”

Marianne laughed at this, and Artie wondered what had been funny, what was worth digging into more. The idea of taking a photo of a loved one’s falling to his death? Or that your phone could actually become a better friend to you if you recorded your whole life on it, not just the good parts?

“Maybe that’s why people do crying selfies now,” Artie said. “Post photos and videos of themselves crying. Have you seen those?”

No encouragement from the room, but a nod from Olivia.

“At first, I thought it was pure narcissism, or actresses auditioning for a part, because it was only pretty girls filming themselves in the beginning, remember? Big eyes, mascara drips, cute sniffles. But then ugly people started doing it too, they started filming their ugly crying faces, and I thought there had to be more to it. So I started reading the captions. Have you guys ever read the captions?”

Still no answer from his classmates, but he had to make the pauses, look up to his audience, pretend they were in this together.

“You get all kinds of stuff in the captions: ‘I may look bubbly and fun, but this is also me, hashtag also me, hashtag real life, hashtag me, hashtag dealing with past traumas.’ Or things like ‘Look what you did to me, Chad!’ All kinds of stuff. One that comes back a lot, though, is this: ‘So I remember how bad I felt.’ ”

This was something to let sit for a second, and so Artie paused again.

“What does that mean, ‘So I remember how bad I felt’? Won’t they be able to remember how they felt if they don’t post it on social media? If other people don’t see it? If they don’t store it in the cloud?”

There hadn’t been a laugh since Marianne’s, a century ago.

“I complain that my phone sends me stuff, but when it sends me a fishing trip memory, what do other people get? A picture of their crying face, which reminds them of that time Chad slept with Lucy? Does anyone want this? Isn’t that already what our brains are for? Shooting bad memories at us at random?”

The number of questions you’re asking, Artie told himself. That’s desperation, pure and simple.

“Not that good memories are much better. I mean, who wants to remember joyful moments? They’re gone forever. You’ll never re-create the exact conditions. Might as well make actual photo albums and look at them. The best times of your life, gathered all together in one place for you to browse and remember how much better things used to be.”

How had he gotten here? Could he even wrap up at this point? What threads were there to bring back together?

“Anyway,” he said, a word they’d been told to avoid. “I don’t need a smartphone to remind me how big of a loser I am. A regular phone is good enough technology. As long as it’s a number my mother can reach, I get to feel bad about my life a satisfactory amount.”

Artie thought it would be clear this was his last line, that improv was over, but after a few seconds of silence, he had to add: “I want to stop now.”

The class started their critique right away.

“He said ‘anyway,’ ” Phil noted.

“That was painful,” said Jo. “Not just him saying ‘anyway.’ The whole thing.”

“Why did you think it was painful?” Kruger asked.

“Because it wasn’t funny.”

When asked to be more specific, Jo explained that Artie was trying too hard to say something.

“Instead of just talking, I mean.”

“I agree,” Phil said.

Olivia was more encouraging, but Artie assumed it was only because he was giving her a ride later and she didn’t want it to be too awkward.

“It was very raw,” she said, “but I think there’s some good stuff to keep digging at. Like, with the randomness of memories. There could be some physical comedy there, maybe, like, when the memories hit him. Or more description of the memories themselves, and how they clash with the photos. Maybe you could show actual slides? From your actual life?”

“If he puts actual slides in, it becomes the Mad Men episode where Draper pitches the Kodak carousel,” Dan said.

Artie hadn’t seen Mad Men, but he nodded anyway.

“Unless he also puts jokes in,” Jo said. “I think the key here is something funny should happen.”

“The Mad Men thing is interesting,” Marianne said. “Artie’s bit could be a parody. Parodies of famous scenes can be great.”

“It’s not that famous a scene,” Phil said. “I haven’t seen it.”

“You haven’t seen Last Year at Marienbad either.”

The rest of the class agreed, over Phil’s objection, that the carousel scene in Mad Men was famous enough that a parody could work, was in fact maybe a great idea, after which everyone started talking about Artie’s improv as if Artie’s intention had been to riff on Mad Men all along. It was too late for Artie to admit that he’d never watched Mad Men, that episode or any other. It didn’t really matter anyway. The world was too full, he thought, and nothing you said would ever be considered original thinking, even when it felt pretty original to you. Submitting your work for critique meant sticking around after a performance in order to hear people talk about other things your performance had reminded them of.

He felt extremely depressed for a minute. He was only ever depressed for minutes at a time, but they were intense minutes, thinking-about-ways-to-kill-himself minutes. His brother had told him once that what Artie felt wasn’t depression, because depression lasted longer than a few minutes. “Then what do I have?” Artie had asked. “What’s my problem?” To which Mickey had said that Artie’s problem was he wanted too much attention. Coming from any other drug addict who went missing every few months, it could’ve been a pot/kettle moment, but Mickey’s goal had never been attention. Artie actually believed that what his brother wanted was the opposite of attention, that the reason behind the drugs was he actually wanted to be forgotten, didn’t even want to have to think about Mickey Kessler himself. Artie sometimes believed that his brother’s hope in disappearing repeatedly was for his disappearances to become so routine he’d reach a point where people would stop wondering where he was, or noticing he was gone at all.

Everyone in the room was still giving their opinion on the Mad Men scene. They’d spent more time discussing it than Artie’s performance by now. Olivia admitted to having been moved to tears by Jon Hamm’s monologue the first time she’d seen the episode, and then even more so the second. Kruger thought that was interesting. He asked the class why they thought it was that a great scene could affect us more deeply the second time we saw it.

“I wouldn’t call the Mad Men scene a great scene,” Jo said.

“It’s about anticipation,” Marianne said. “You know something amazing is going to happen, and so you’re already wide open when it comes. You take it in full force.”

“It should be the opposite, though,” said Phil. “Full force is when it takes you by surprise. If you know in advance what’s going to happen, it should all come to you diminished.”

“That’s true if the scene is just all right,” Marianne said. “If a scene is just all right, you dissect it the second time you see it. You look for the tricks and the ropes and understand how it works so well. But if it’s great, you don’t even think to look for the ropes. You’re blinded to the ropes. You end up thinking maybe there aren’t any. That’s why it becomes even more powerful.”

“You don’t see the ropes in the Mad Men scene?” Jo asked.

“We’re not talking about Mad Men anymore. Ben’s question was about great scenes in general.”

“I’d be happy with people just laughing the first time,” Artie said, and it was his most successful joke of the day. Even the corner of Kruger’s mouth moved up a little.

“Do you have questions for the class?” he asked Artie, a ritual query that marked a student’s exit from under the microscope and reentry into society.

You weren’t supposed to have questions at the end of workshop. You were supposed to thank everyone for being so thorough (“What a tremendous help!”), leave the stage humbly, and try to wait until class ended to have your breakdown.

“I don’t think so,” Artie said. “I think you guys were pretty thorough.”

He was still standing next to the gigantic photo of himself.

“I’m sorry you had to see this,” he added. “I don’t know why I talked about my dead grandfather there. That was lame.”

“It wasn’t the worst part,” Dan said.

Artie swore he hadn’t been fishing for sympathy. “I know emotion is the enemy of comedy,” he said.

“Says who?” Phil said.

“Well, it’s not like your bit was particularly moving,” Marianne said.

“I think our Artie here has been reading Henri Bergson,” Kruger said.

“I don’t know who that is,” Artie admitted, and explained it was just something his mother had told him earlier on the phone. That comedy couldn’t be moving, or else it stopped being funny.

“Well then, I guess your mother’s been reading Henri Bergson,” Kruger said.

“Do you listen to everything your mother has to say about comedy?” Jo asked.

Only Marianne had ever read Bergson’s book about laughter. She said it was very interesting, but written before Charlie Chaplin or anything truly funny, so maybe it was outdated.

“Chaplin is moving and funny,” she said. “I wonder where he would have fit in Bergson’s theory.”

“Can you guys think of other comics that move you and make you laugh at the same time?” Kruger asked. “Specific bits?”

He didn’t like asking for names, but sometimes you had to. He assumed it made his students uncomfortable to be asked for favorites, because they knew comedy was a small world, and anyone they named had the potential to be their teacher’s nemesis.

“Andy Kaufman,” Jo said. “On Letterman. When he calls his grandmother on the phone.”

“Louis C.K., the old Chinese lady,” Dan said. “Bill Burr and the ape.”

“Dave Chappelle, the Bourdain suicide,” Marianne said.

“Manny Reinhardt,” Olivia said. “The bit about his blind neighbor.”

“I don’t hear a lot of female names,” Phil complained. You could always count on him to say something like that.

“Well, why don’t you give us one?” Marianne said.

Olivia said that it was easier for a man to be funny and moving at the same time, because all a man had to do to move an audience was let it know that he was not entirely oblivious to his surroundings, and sometimes even capable of emotion, and that was enough to break people’s hearts.

“Whereas women,” she went on, “you expect them to be full of doubts and feelings. You expect them to notice how sad everything is all the time. So it doesn’t have the same impact when they let you see their humanity. It’s never poignant. It’s almost just annoying.”

Phil thought that was sad and unfair. He wasn’t sure he agreed with Olivia, but in order to repair centuries of injustice toward women, he’d pretty much decided to never contradict one again, even though it seemed to make every girl he knew uninterested in having any kind of conversation with him.

The room was silent for almost a minute after Olivia spoke. Not that she’d said anything deep. It wasn’t the silence a group made while thinking. It was the silence of collective low blood sugar, of class break due imminently.

“You know what?” Jo said, bringing everyone out of their torpor. “The more I look at Artie next to that big photo of himself, the funnier it gets. Maybe it’s even moving, too. Maybe I’m moved by it.”

They all looked at Artie again, and then at the photo of younger, pimply Artie beside him.

“You’re right,” Marianne said. “I feel something.”

Artie stood straighter and prouder by the paperboard.

“No no no no no,” said Jo. “Don’t do anything stupid. I think it’s stronger if you just sit there and look a little lost.”

Artie grabbed a stool and sat on it. Everyone stared some more. Jo gave a couple of directions (“Maybe sit in front of the photo rather than next to it,” “Try to forget about the photo altogether,” “Forget about us”), and Artie followed them. He started thinking about other things, about how he should call Ethel, and how he should try to befriend his brother when he showed up again. It wasn’t the first time he’d formulated this project. Two years earlier, he’d started reading more novels so he and Mickey would have something to talk about. Conversations about books had been a little stilted, though, Artie remembered, a little forced. They’d ended up putting distance between them rather than bringing them closer. Artie thought back on how it felt like they hadn’t been reading the same novel sometimes, like he’d bought a counterfeit edition, or the librarian, after taking a quick look at him, had decided to lend him a simplified one, the for-morons version, with just the biggest plot points and none of the secondary actions and main undercurrents that Mickey—who’d read the full version, for smart people—spoke of. He’d had to explain to Artie that it wasn’t so much that Jake Barnes was doing the decent thing by not sleeping with his friend’s ex in The Sun Also Rises as that his dick had been shot off in the war. Artie hadn’t caught that part about the dick. Which seemed pretty instrumental to the plot. Talking about books with Mickey had been like attempting conversation from two sides of a precipice—Mickey on one, Artie on the other, Mickey trying to get him closer to the edge, Artie trying not to fall in.

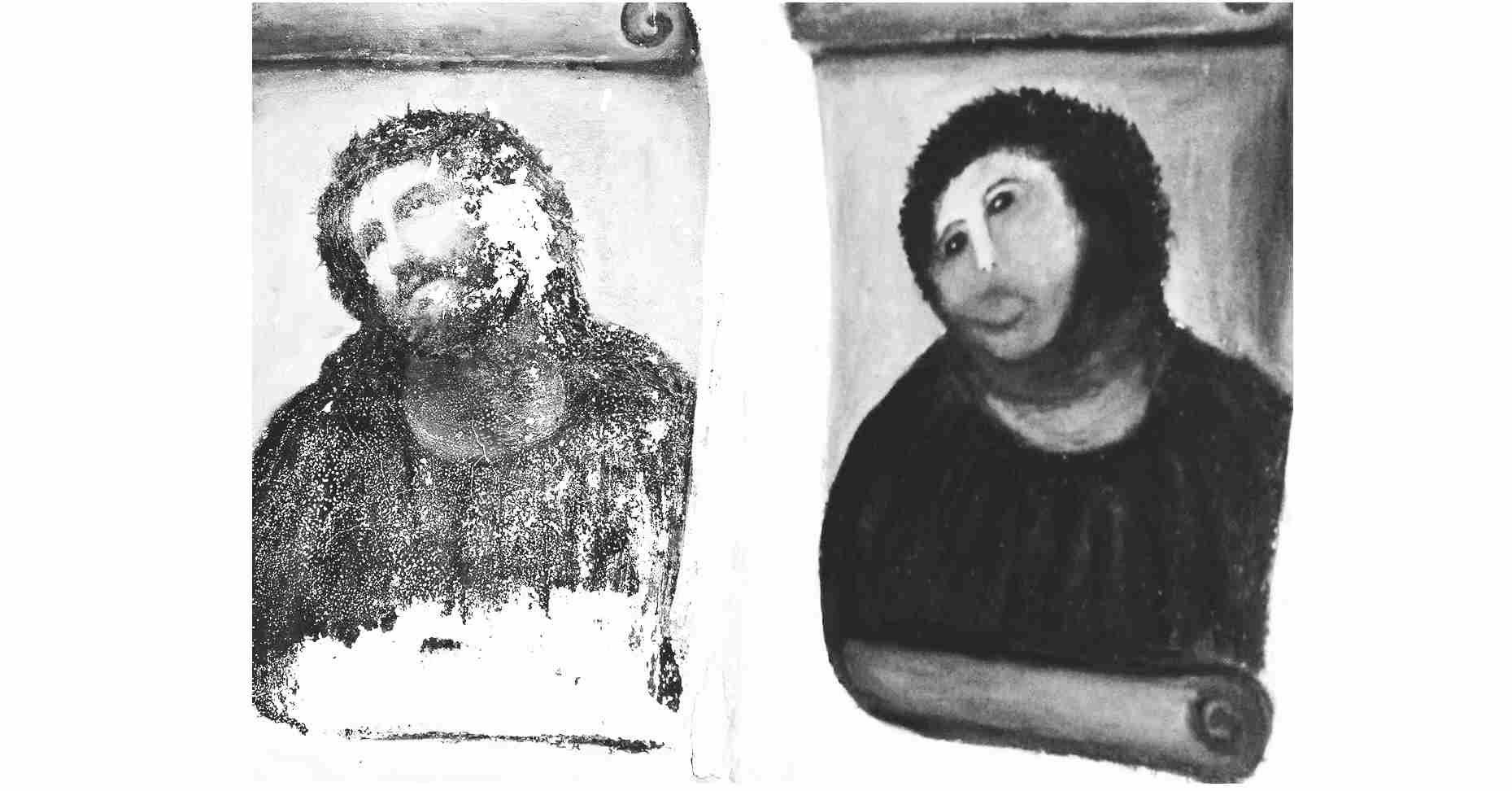

Perhaps he should get into heroin, Artie thought, his classmates still staring, some directly at him, some at his old photo. Perhaps he could share a heroin addiction with his brother. He’d tried heroin, a handful of times, to see what the fuss was about. Heroin was pretty great, but not quite to the point that he’d want to devote his life to it. You can’t even get addicted to heroin, he’d berated himself more than once. He was under the impression that addictive personalities lived life more fully, that by being a restrained, solid kind of guy, he was missing out not only on the intricacies of world literature’s best storylines but on a much bigger secret. He had this idea that a person’s existence was like a big Renaissance oil painting, full of details and nuances and reflections, and that his had been painted over by that lady who’d butchered her local church’s fresco by wanting to be useful. All blobby brushstrokes and flat tints. Almost blurry. When he’d first seen the meme, the portrait of Christ next to the old woman’s restoration of it, he’d thought: Mickey on the left, Artie on the right.

He thought about how empty his life would be if Mickey disappeared for good this time, and when he remembered that people were watching, Olivia, his classmates, his teacher, it was because they were all laughing.