7

This was getting too long for an exercise, but Dorothy was intent on keeping the mood light. She tried to guess who the shooter was. She listed a couple of undergrads whose names she remembered from group emails—kids who sent letters to the entire department whenever injustice occurred somewhere in America, demanding a statement be made in solidarity with the victims.

“Though I guess that’s exactly the type of kid we have nothing to fear from,” she said to Sword. “If what you demand at their age are statements, odds are you’ll live a pretty uneventful life.”

She was biting her nails. Sword hadn’t said much the whole thirty minutes they’d been stuck together in the conference room, and she was starting to get annoyed with him. It was just like her, she thought, in a life-and-death situation, to direct all ill thoughts not at the shooter lurking around but at the poor guy who failed to entertain her while it happened. If she survived today, she’d have to write about it. The thought made her a little sad.

“It’s probably a kid no one has really noticed before,” she said. “The perfectly average student.”

“Why are you so sure it’s a student?” Sword asked.

“No one over twenty-two has the energy.”

“So, not even a grad student.”

“Definitely not one of mine,” Dorothy said. “The MFAs are too lazy for that kind of…effusion. And comedians don’t deal with anger that way.”

“Right,” Sword said. “You guys kill people with words.”

His earnestness gave her chills. Did people really say things like that? On some level, Dorothy knew that they did, but she’d never quite believed it. You guys kill people with words. Jesus. Maybe it was better when he didn’t talk. No wonder his wife was suicidal, she thought, even though she wouldn’t have called it a thought—word combinations of this kind appeared in her head like well-placed commas in a sentence: she barely noticed them.

Sword understood he’d said something wrong. “I think I just found out what offends you,” he said.

“I told you,” Dorothy said. “I don’t get offended.”

“Metaphors. I offended you with my metaphor about killing people with words.”

“You didn’t offend me. I just found it ridiculous, is all.”

“I should’ve known comedians don’t like metaphors. Metaphors are just one more thing to make fun of.”

“Bad ones are. But some metaphors are fine. They can even be useful sometimes, in a medical context.”

“What’s so wrong about ‘killing with words’?”

“Well, it’s cheesy, for one,” Dorothy said. “It’s grandiloquent. It’s vague.”

Vagueness was, to her mind, the biggest crime of them all. There was a class of people, though, who thought there was power in vagueness, who mistook imprecise writing for a reflection of life’s deepest ambiguities. She realized Sword might be part of that group.

“Vague isn’t necessarily bad,” he said. “It mirrors the human experience.”

How was this guy allowed to teach English? Dorothy wondered. She’d had respect for him before.

“Good writing is supposed to transcend human experience,” she said, “not just mirror it. Otherwise, all I would have to do for critics to call my next show a masterpiece would be to write an hour’s worth of random words, and I would get blurbs like ‘Astounding! Just like life! Makes no sense at all!’ That’s some bullshit. Good writing has to be clear at all times, controlled, even when it describes ambiguous situations.”

“Some people like to get lost,” Sword said, a sentiment Dorothy chose to ignore.

She went back to biting her nails. She and Sword were sitting next to each other on the floor, along the wall that the door was on, at an angle they assumed the shooter wouldn’t be able to see them from if he peeked through the narrow window above the knob. They were starting to get cramps from keeping their knees folded so close against their chests, but they didn’t dare stretch their legs. There was still enough daylight filtering through the windows that any movement could drag along its own shadow and reveal their position.

“I think what I don’t like about a vague metaphor is when everyone pretends they see exactly what the author meant and I’m the only one to not get it,” Dorothy said. She hated to find this out about herself, that she apparently was the kind of person who, faced with the threat of imminent death, couldn’t stand silence. When imagining her last moments (something she’d done countless times since childhood), she’d always pictured herself as a wise, Buddha-like figure, someone who would look inward and make peace with herself. Her father had been that way. But it wasn’t happening for Dorothy. In what could be her last moments, it turned out what she needed was to yap about bad writing, to keep doing exactly what she’d been doing her entire life.

“I still don’t see what’s vague about killing someone with words,” Sword said.

Dorothy explained it was the exaggeration around artists in general that pissed her off. Like she could kill anyone with her work, she said. She couldn’t even flick anyone with a joke.

“Manny Reinhardt punched someone in the face,” Sword said.

“Exactly,” Dorothy said. “He used his fists.”

Where did this idea come from, anyway, that art had to inflict pain on its audience? That that was the goal—to kill it, slay it, break its heart, punch it in the gut?

“I think it’s because we know that artists suffer for their art,” Sword said. “So we think art that is successful is art in which that pain gets transferred to the audience somehow. Shared.”

“Why does everyone have to imagine artists bleeding on the page? Consumed, going mental?”

Writing her shows had always been painful for Dorothy, but she’d decided long ago that she’d have all her molars pulled before she admitted it. She thought only great comedians were allowed to admit to suffering, that admitting to it herself would only get people wondering who the hell she thought she was, and why she believed her work was so important that they cared if it got written or not, performed or not. “If it hurts so bad, why don’t you quit?” was what she was afraid to hear. No one would miss Dorothy Michaels’s next hour of comedy, no one would sit in contemplation of what could’ve been.

“You say you hate exaggeration around artists,” Sword said, “but comedians are the ones who came up with all the death metaphors. Dying onstage when they suck, killing when they succeed.”

He had a point, but Dorothy didn’t feel like giving it to him. She looked at her phone, where she hoped to see news that the shooter had been apprehended. The “situation” they were in still showed as “unfolding.”

“What about we stop talking about death and killing for a minute?” she said. “Can we do that?”

They talked about their mothers.

Sword’s had been dead five years, so he only had nice things to say. He wanted to hear about Dorothy’s mother’s immigration story, though, how she wound up in Texas, and why Dorothy never talked about being half-Italian in her comedy.

“I never found the fact funny,” she said. “Americans only know about Italian Americans anyway, not Italian Italians. It wouldn’t work.”

“You speak Italian with your mother?”

“She never taught me. At the time, people thought bilingualism made children stupid.”

“She must regret it now,” Sword said.

“I learned it later. It’s just I have a terrible accent. I sound like Brad Pitt in Inglourious Basterds: ‘Aweeva-durtchi.’ ”

“I love that movie,” Sword said. “Brad Pitt. What an interesting trajectory.”

“He’s got range,” Dorothy said. “He’s a great comic actor.”

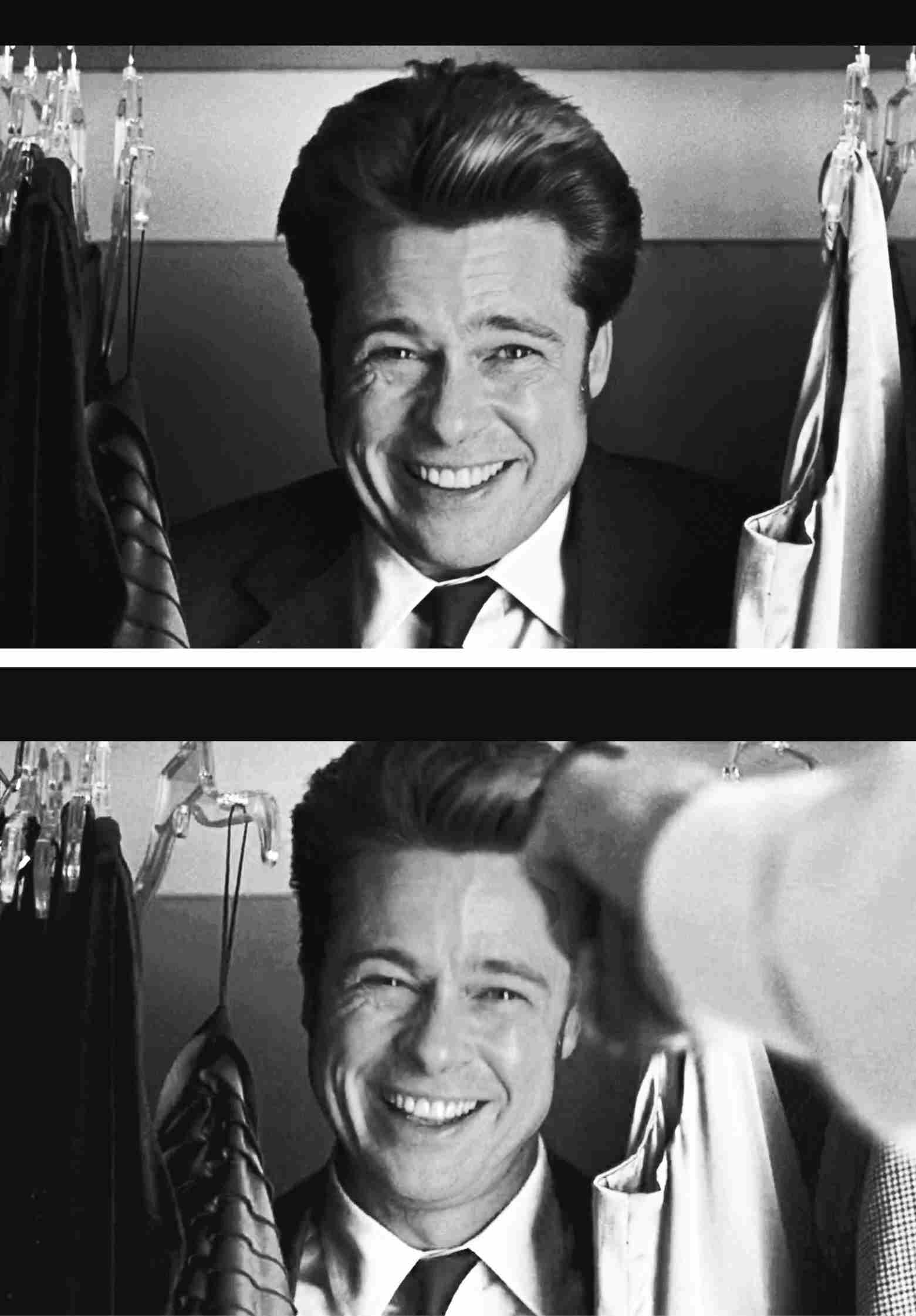

Of all of Brad Pitt’s career, the scene that came to Dorothy’s mind in that moment was the one where he gets shot in a closet in Burn After Reading. She’d laughed so hard at it in the theater. The work his face did in that half second between being discovered and being shot dead—there was a whole story there. As in: someone could’ve written a novel about that half second. Terrified idiot foresees way out of potential violent death by telling his killer a funny story about how he ended up hiding in his closet. That the audience never gets to hear the funny story in question, that George Clooney is so shocked to find Brad Pitt between his shirts that he shoots him on sight, is of course the perfect move. It surprises and makes sense all at once. Yet the beauty of the scene lies in our belief that Brad Pitt’s character has a story to tell. That if Clooney doesn’t shoot, we’ll get to hear it.

But Clooney shoots.

Dorothy image-searched “brad pitt closet scene” on her phone and only realized as she showed Sword the results how unsavory that was.

“Are you giving me options of faces to make when the shooter gets here?” Sword said.

Dorothy apologized and pulled her phone back.

“I wasn’t thinking,” she said.

Sword imitated one of Brad Pitt’s closet faces (the first one, with the double chin) to let Dorothy know she was forgiven.

Dorothy hadn’t thought about her own face so far. Only the shooter’s. She’d been so focused on trying to guess who the shooter was that she’d forgotten to think about what her last words should be if he got to them, or the last face she’d make. Sword said he already knew what his last words would be, that that was something he’d decided upon years ago. Dorothy thought that was the first interesting thing he’d said. She asked him what the words were.

“I’m not telling you my last words,” Sword said. “We’re not dying yet.” They still hadn’t heard a single gunshot.

“But how did they come to you? Did it sort of hit you, or is it something you took days to think about?”

“It took about an afternoon,” Sword said.

Dorothy couldn’t decide whether that was long or short.

“Is it a sort of all-encompassing statement about your life?” she asked. “Is it a whole sentence?”

“I’m not telling you anything. It’s between my wife and me.”

“Your wife knows what your last words will be?”

“Of course she does. She’s the one who wanted me to pick them. She told me hers, too.”

“But that’s the ultimate mystery,” Dorothy said. “Why would she stay with you now that she knows what you’ll say last?”

“She said it was in case I die and she’s not around. So she doesn’t have to spend the rest of her life wondering what my last words were.”

“What a fun home life you have,” Dorothy said.

“Or vice versa,” Sword went on. “If she dies first.”

“So you can’t even change them if she dies first and you remarry?”

Sword looked through the window and thought of Baudelaire: “Quand le ciel bas et lourd pèse comme un couvercle”—the sky as a pot lid, weighing on everything. He’d considered Baudelaire for his last words, and other French poets, but it had felt a bit solemn in the end, a bit too self-important.

Dorothy asked again what the words were. She didn’t want silence to take hold.

“Just look at it as a silver lining,” Sword said. “If the shooter makes it to this room, you’ll get to hear them.”

“Only if he shoots you first,” Dorothy said.

“True.”

“If I go first, I have to warn you, I have no good last words to offer. I’d rather focus on last expressions, I guess. The last face I’ll make. When he shoots me, if there is indeed a shooter in the building, I don’t want to make a stupid face, like the deaths you’re not supposed to care about in the movies.”

“Why does it matter? Are you afraid the shooter will be filming you?”

Dorothy hadn’t even considered the possibility.

“I don’t want to give him the satisfaction, is all,” she said. “That’s why I’d like to guess who it is before he gets here. So at least I’m not taken by surprise when I see what he looks like. A surprised face would be the worst.”

She wanted defiant, a defiant expression. She wanted dignity.

They heard footsteps in the hallway.

Sword inched closer to her and took her hand. The footsteps got closer, too. Dorothy held her breath. She wanted to block her ears, but also to leave her hand in Sword’s (when was the last time someone had held her hand?), and so she just started humming, which she thought would cover the sound of the shooter’s steps.

“What are you doing?” Sword whispered. “He’s going to hear you.”

The footsteps in the hallway stopped a split second after Dorothy went quiet. Had the shooter heard her quit humming? Weren’t the walls supposed to be soundproof anyway? Hadn’t Sword himself told her this? That you could hear what happened in the hallways, but couldn’t, from the hallways, hear what happened in a classroom? The shooter couldn’t have heard her, Dorothy thought. She’d hummed the kind of hum that only echoed in the hummer’s skull.

They heard clicking sounds. The sounds came from right behind the door. They were familiar clicks, quick, bubbly, unnerving. Sword mouthed the words Is he texting? and Dorothy tasted tears coming up her throat. She wasn’t going to cry now, was she? She wasn’t a crier. More clicking. A couple of seconds of silence, then a swishing sound. The sound of a text being sent. The shooter had sent a text. Dorothy oddly expected to be the recipient of that text, but her screen remained dark. The shooter sighed behind the door and started typing again. One click sound per key hit. She never understood people who kept those sounds on. Did they do it to prove to everyone around them that they had people to talk to? Important messages to pass along? And what about those guys who walked the streets with their phones in front of their mouths, Dorothy wondered, who held their phones like tartines, like they were about to eat them? They clearly wanted strangers to witness their conversations, but why? And why was she thinking about different categories of people she despised right before dying? She squeezed Sword’s hand.

Behind the door, the shooter finished typing another message, but the sound that followed wasn’t that of a text sailing off, or an email. It was a sound Dorothy didn’t recognize, that made her think of a mother shushing a child. Maybe it was a tweet? Maybe the shooter was tweeting about this? She’d never written a tweet, didn’t know the sounds Twitter made when you…sent one? They heard the shooter sigh again. Dorothy thought she recognized Artie’s way of sighing, the characteristic uptick at the end.

I think it’s Artie, she mouthed to Sword.

Arthur Kessler? Sword mouthed back.

Artie was probably looking for her specifically, Dorothy thought. She’d been hard on him in improv class two days ago. Not as hard as she could’ve been, but she’d said things—that he was closed off like bad shellfish, that you couldn’t get anything unrehearsed out of him, that he had to be more generous with his stage mates, and give them something to play with, and try stuff, and shift the pace, take more initiative—and now he was going to kill her for it. Was it better to be killed by someone you knew or by a total stranger? Artie’s footsteps resumed. They took him three doors down, to the bathroom at the end of the hallway. Sword’s office was just across from that bathroom, and he was familiar with the double squeak the bathroom doors made.

“He’s taking a bathroom break,” he told Dorothy.

“Are you sure?”

“A hundred percent. The door closed behind him.”

Dorothy said this was their chance to escape, but Sword wasn’t convinced.

“Maybe that wasn’t the shooter,” he said. “Maybe that was just someone who didn’t get the alert on his phone.”

“He was using his phone,” Dorothy said.

“Maybe he didn’t get the message.”

“I don’t understand…do you want to die here? Do you want to be killed by a Ryan Gosling look-alike?”

“Artie Kessler doesn’t look like Ryan Gosling. He looks more like a young Paul Newman.”

“All good-looking people look the same to me,” Dorothy said.

She’d only ever fallen for ugly guys. Ugliness was superior to beauty in that it lasted much longer, she liked to say, paraphrasing Serge Gainsbourg. No one she’d ever said this to had known Gainsbourg to be the author of the quote, and so she’d claimed it as her own more than once, something she felt guilty about right now, something she wished she could correct before she died.

Sword was still holding her hand.

The expectation was they should sleep together, she thought. Maybe that was why he refused to leave when they had an out—maybe he felt they hadn’t taken advantage of their being locked in a room together, all that electric, fear-generated energy.

“We need to leave now,” Dorothy said. “We’ll reminisce about our near-death experience at a later juncture. We’ll get drunk over it, I’ll buy you any scotch you like. I’ll even sleep with you if you want. But we need to get the fuck out of here right now.”

Sword said there would be no sleeping together. “I love my wife,” he said, and the simplicity of the sentence touched even him.

Dorothy was annoyed that he could think she hadn’t figured that out.

They left the room.