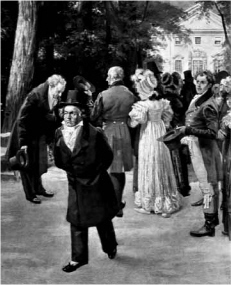

‘HE IS PERFECTLY entitled to regard the world as detestable, but that does not make it any more enjoyable for himself or anyone else.’1 This could be an exasperated adult speaking about a difficult adolescent; but it is actually the suave, sophisticated poet Goethe despairing about the behaviour of Beethoven. When, strolling together in a park, so the story goes,* they saw the royal family coming towards them, Beethoven pressed on: he went through the throng of Habsburg princes and sycophants like Moses parting the Red Sea. He then turned around and, much to his amusement, saw Goethe stand aside, his hat in hand and bowing obsequiously, to let the procession proceed.3

This incident and much of Beethoven’s life illustrate the extent to which, within a few years of Mozart’s premature death, a talented artist could assert his independence and yet survive.4 Although Beethoven often felt financially insecure, he did not have to hang about ingratiatingly and hope that some chamberlain would arrive with a bag of ducats. No longer was the musical composition on a shopping list of an aristocrat preparing the day’s entertainment, or ‘made to order’ to embellish the worship of God. This argumentative, ugly, pockmarked and slovenly man could now make a reasonable living from creating his own works of art. Music had become an object in itself, each work entirely the inspiration of the individual.

The audience could still be ignorant and abusive, as on the occasion when an empress dismissed a Mozart opera as ‘German hogwash’.5 Or it could even be intelligently critical. But gone were the days when a Medici prince could interfere and require Alessandro Scarlatti to make an opera nobler and more cheerful; or a Habsburg emperor could be concerned with the number of notes in an opera by Mozart.*

Beethoven, Goethe and the Royal Family

This new environment was attributable not just to the French Rev-olution which weakened the rigid framework of social structures. There was now an entirely new attitude towards art. Goethe caustically described the constraints by which artists had previously been circumscribed: ‘A good deal can be said of the advantages of Rules, much the same as can be said in praise of bourgeois society. A man shaped by Rules will never produce anything tasteless or bad, just as a citizen who observes law and decorum will never be an unbearable neighbour or an out-and-out villain.’ He continued: ‘On the other hand, the Rules will destroy the true feeling of Nature and its true expression!’7

So, while all great composers push out frontiers, Beethoven could break the rules in leaps and bounds. He remained fundamentally ‘classical’ in his style. Yet he surprised listeners of his First Symphony in C major by beginning it in F major.8 He began the Fourth Piano Concerto with the solo piano, a complete change from all previous concertos. He started the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata unconventionally with a slow movement.9 The final movement of the Ninth Symphony begins with a shocking chord. These are just obvious examples. Why did he do it? For his art. He went so far that his successors found that he had taken certain types of instrumental music almost to the limit, and he was virtually impossible to follow: Brahms just did not feel confident tackling a symphony until he was in his forties.10

Ludwig van Beethoven was born around 16 December 1770 in Bonn, the residence of the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. A trivial consequence of the momentous French Revolution was that Bonn became an unbearable place in which to live. Beethoven moved to Vienna, a year after Mozart died. He withdrew increasingly into his shell as his sad life progressed, with his hopeless love life, his deafness and the family troubles with his nephew. His middle years, a period of great creativity, were accompanied by worries caused by the Napoleonic wars. By the start of the Congress of Vienna in 1814, other tastes and trends were developing, apparent in the operas of Rossini and heard in the new romantic sounds and textures coaxed out of the orchestra by Carl Maria von Weber.

At the end of his life, Beethoven lived in self-inflicted squalor, apparently drinking a bottle of wine with each meal.11 Rossini was so appalled when he saw him that he tried fundraising to help him, but got no support. People gave Beethoven up as a lost cause. But, in those last years, he wrote the Ninth Symphony. He seems to have thrown down the gauntlet to the next generation, almost saying: ‘try beating that!’12 It was a long time, if ever, before anyone did, or could.

BONN

We start far from Vienna. Beethoven’s grandfather, the son of a baker, was choirmaster in a church in Louvain, close to Brussels, where the family had earlier been involved in the lace business. Archbishop Clemens-August of Cologne invited him to travel 100 miles to Bonn and join the court music staff. He rose to become Kapellmeister, in the year that the archbishop died, nine years before Beethoven was born. This appointment was the kind of prestigious position which Leopold Mozart craved for himself or his son.

The highly cultured Archbishop Clemens-August was the brother of the Elector of Bavaria who in the 1740s briefly interrupted the Habsburg succession and became emperor. The archbishop resided in Bonn, well away from the Free City of Cologne, with whose burgers he had a very shaky relationship. He built himself several palaces, including a large ‘pleasure’ palace in nearby Brühl. This had a magnificent rococo staircase, and, in the garden, a summerhouse called the ‘Indian palace’ even though its style was Chinese. He enjoyed falconing, riding on his English hunters and being entertained by his jester. He also played the viola da gamba. There is a picture of him at a masked ball in the 1750s with the musicians working away in two bands on either side.13 (See colour plate 10.)

This relaxed and cultured life was spent against a background of rising prosperity.14 The agricultural revolution caused a considerable boom in property values. There were improvements in diet and hygiene, with a relatively low incidence of disease. The population was growing fast. There was, however, unemployment and vagabondage. France, increasingly unstable, was not far away.

The Kapellmeister’s son, Beethoven’s father, sang in the choir. He married, beneath his status, the widowed daughter of the head cook in one of the palaces. He took to drink and it was an unhappy marriage. Beethoven’s mother, who was never known to laugh, regarded life as ‘a little joy – and a chain of sorrows’.15 They had three surviving children, first Ludwig, then Caspar born in 1774, and Johann born two years later.

Beethoven was born at the back* of a modest house in the Bonngasse, a few yards from the market place and the gate leading out to Cologne, some sixteen miles away.16 In later years, he was unclear of his exact age. He was probably born on the day before he was baptised, 17 December 1770. At any rate, baptism had to take place within three days of birth. Around sixteen months earlier, Napoleon had been born in Corsica.

Bonn was rich in musical talent. The Beethovens’ neighbours included the violinist Franz Ries, a former infant prodigy; his son Ferdinand was one of the brilliant pianists in the first years of the 19th century. Nearby lived the horn-player and dealer in printed music and musical instruments, Nicolaus Simrock, who started one of the leading music publishing businesses of the 19th century. Also nearby was the family of Johann Peter Salomon, who at the age of thirteen had been appointed to the Bonn court orchestra.17 By the time of Beethoven’s birth, Salomon had become an impresario. The city continued to attract musicians. When Beethoven was fifteen, Anton Reicha from Prague came as a flute player in the court orchestra; he would eventually move to Paris where Liszt, Berlioz and César Franck became his pupils.

Beethoven showed early musical promise: he performed in his first public concert before he was nine and issued his first composition by the age of twelve. His father and local musicians taught him the violin, viola, horn and clavier. He was also taught by the court organist, Christian Neefe, a ‘rare enthusiast for the music of JS Bach’.18 He deputised for Neefe and, at twelve, he was harpsichordist with the court orchestra. Despite his technical competence, he was not presented as an infant prodigy.

Beethoven must have witnessed the colourful celebrations when the elector-designate visited Bonn in 1780. In an important move, the Habsburgs had arranged that on the death of the incumbent, Emperor Joseph’s brother Max Franz would succeed to the archiepiscopal throne. A million florins had been scattered in order to secure the votes of the canons of Cologne and Münster, thus, as Frederick the Great acidly described it, ‘making sure of the inspiration of the Holy Ghost’.19 As Max Franz was already grand master of the Teutonic Knights, an ancient and noble order of knighthood which was still influential, he was set to become the most powerful ecclesiastic prince ever seen in the Holy Roman Empire. He had previously been destined to become military viceroy of Hungary; but several operations to cure knee trouble meant that this was not a realistic position for him to hold.

The new archbishop, who succeeded in 1784, wanted to reorganise his court and implement economies, like his Salzburg colleague. The music department of 49 musicians was reviewed.20 Neefe’s salary was halved, and it even seemed at one point as if Beethoven was going to supplant him. But this matter was resolved. Some years later, Beethoven wrote to Neefe: ‘I thank you for the advice you have very often given me about making progress in my divine art. Should I ever become a great man, you too will have a share in my success.’21

When he was seventeen, Beethoven was sent to Vienna to improve his musical experience. He may have had a few lessons from Mozart. But within a fortnight, he heard that his mother’s health – she suffered from consumption – was deteriorating badly, and he had to return home quickly. She died, and was closely followed by her daughter, aged a year and a half. After this, with his father suffering increasingly from alcoholism, Beethoven had to take hold of family affairs. He managed to get half of his father’s salary assigned to him. When his father died at the end of 1792, the archbishop is said to have made some wry remarks about the adverse effect of the death on the archiepiscopal revenues from liquor tax.22

The next few years were spent in Bonn. Beethoven was one of the four viola players in the court orchestras. He wrote songs, piano music and chamber music. He frequented the Zehrgarten tavern in the market place, a meeting place for intellectuals. He studied philosophy at Bonn University and read the poetry and plays of Klopstock, Goethe and the young Schiller whose early play Die Räuber had recently been published. He imbibed the literature of the Enlightenment in a way in which no great composer before him had the opportunity to do.23

He was a frequent visitor to the house of the Breuning family, who held a middle-class salon for artists, musicians and writers. Helene von Breuning, whose husband had been killed when the archbishop’s town residence had been burnt down in 1777, acted as a second mother to Beethoven. He fell in love with her daughter, Lorchen (Eleonore), although she, in the end, married Franz Gerhard Wegeler, a student who had lodged with them. In the year before he died, Beethoven wrote to Wegeler: ‘I still have the silhouette of your Lorchen, from which you will see that all the goodness and affection shown to me in my youth are still dear to me.’24 Just before he left Bonn, Beethoven and Lorchen had some bust-up, a ‘fatal quarrel’ of which he was ashamed. Was he too impetuous?

Haydn passed through Bonn on his way to and from London. Having looked over one of Beethoven’s cantatas, possibly one written to mark the death of Emperor Joseph II, he invited Beethoven to Vienna to take lessons. Beethoven was encouraged and supported in this by another regular visitor to the Breunings, Count Waldstein, who was in Bonn as a novice of the Teutonic Knights.25 So, aged 22, Beethoven set out for Vienna again. On his departure, his friends assembled an autograph album. Waldstein wrote in it: ‘With the help of hard work, you shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.’ Lorchen wrote, more poetically: ‘Friendship with one who is good lengthens like the evening shadow until the sun of life sinks.’26 And she gave him the silhouette.

EUROPEAN UPHEAVAL

There were very good reasons for Beethoven to get out of Bonn and stay away. During the time that he had been playing the viola in the orchestra, Europe had entered a most turbulent period. He was seventeen when the first public events of the French Revolution took place in early 1787. With Bonn little further from the French border than London is from Birmingham, Beethoven will have become aware of the limitations, indeed the dangers, of remaining there.

There were many developments which brought France to revolution, not least the new thinking of the Enlightenment. The mention of a few of the stresses, strains and fast-moving events should be sufficient to describe the context for Beethoven.

The much-detested King Louis XV, before whom young Mozart had performed, died of smallpox in 1774.27 He was succeeded by his grandson, who married Empress Maria Theresa’s youngest daughter, Marie Antoinette. The French government’s finances were chaotic, partly because of war in America: bankruptcy was declared in August 1788. The underlying economic situation was dire: in the 60 years before 1789, grain prices in France rose three times as fast as wages did. By 1789, the cost of bread absorbed nearly 90 per cent of a workman’s resources.28 A free trade treaty with England led to serious unemployment in major textile centres. In 1787–9 there were bad harvests.

Louis XVI tried to respond to demands for reform:29 France had the best roads in Europe, Paris was being rebuilt, social welfare was being extended, national income and productivity were improving. And when the Bastille fell on 14 July 1789, there were actually only seven prisoners in it.30 But it was too late. The most risky moment for a bad government is when it starts to reform.31 The middle classes, which the ancien régime excluded from high office, felt deprived and therefore combined with the lower classes to seize power. Feudalism and aristocratic privileges were abolished and church property was nationalised. The disruption continued. In June 1791, the king and queen decided to run for it; but they were stopped in Varennes, a village halfway between Paris and Cologne.32 A grocer aptly named Monsieur Sauce found them walking along the street knocking on doors to get a change of horses. The suspicion that Louis had fled in order to raise an invading army was one factor which led to his execution a year and a half later, and to Queen Marie Antoinette’s nine months after that.

16 October 1793: Queen Marie Antoinette is taken to the guillotine

War was needed to deter foreign invasion and to put an end to the use of Coblenz, only 40 miles up the Rhine from Bonn, as a base for émigrés such as the king’s brothers, the Counts of Provence and Artois.*War would also unite the disparate revolutionaries. At the end of 1791, the French gave the electors in the Rhineland an ultimatum to halt the émigré activity. After the Habsburgs offered to protect the electorates, France declared war. Shortly thereafter, the mob stormed the Tuileries Palace, and Louis XVI effectively lost all authority. The following month, just a few weeks before Beethoven left Bonn, half the prison population of Paris, well over 1,000 people, were massacred.33 The guillotining of Louis XVI sent shock waves through the courts of Europe, as did the subsequent Terror of 1793–4.*

The war waged by France evolved from a defensive one to an offensive one, as Napoleon progressed from being merely a senior officer to being first consul in 1799. Four years later, in Notre-Dame, he crowned himself emperor of the French in the presence of the Pope. Yet, less than ten years after his coronation, Napoleon’s empire had collapsed. These tumultuous events were compressed within only 30 years; when Napoleon fell, Beethoven had a further thirteen years of his life left.

BEETHOVENIN VIENNA

It made sense for Beethoven to get out of Bonn. The plan to study with Haydn took him to Vienna. At the time he made the journey, French armies had overrun the entire Austrian Netherlands and the bishopric of Liège, not far from Bonn; Mainz and Frankfurt had just fallen. There was complete chaos. Ignoring ‘camp followers’, the French armies in the Rhineland required provisioning for about a quarter of a million people. They had to fend for themselves. They seized wine, coffee, cocoa, clothing, boots, shoes, mattresses, blankets, linen, soap; they would also force local labour to construct fortifications, build roads, make uniforms and join up.34 They exacted forced loans. Beethoven found himself in the centre of all this.

In his diary, Beethoven recorded giving his driver a tip because ‘he drove us like the devil, at the risk of a thrashing, right through the Hessian army’.35 Although the fortunes of war ebbed and flowed, the economic life which supported the lavish courts of the ecclesiastical princes was simply shattered. Trade in the city of Cologne was badly hit by Napoleon’s economic sanctions, and the closing of European ports to British goods: although it was upriver, Cologne was a city where trade in colonial goods such as tobacco was important.36

When Beethoven arrived in Vienna in late 1792, the atmosphere was jittery and remained so for several decades to come. Besides, there had been a change at the top. Earlier that year, Emperor Francis II succeeded his father Leopold, who died after being bled excessively as a cure for a respiratory ailment. Fearful of the events overwhelming his uncle in France, Francis implemented reactionary policies. In summer 1794, a drunken army officer revealed a plot to overthrow the monarchy.37 Forty-five others were arrested with him, although many of them were guilty of little more than inflammatory rhetoric. Several were executed, while the rest got lengthy prison terms. Beethoven wrote: ‘Here many “important” people have been rounded up, it is said, to pre-empt a revolution. But I reckon that there won’t be a revolution so long as the Austrian has his brown beer and sausage.’ He added: ‘You wouldn’t want to speak too loudly here, or the police will lock you up.’38

STUDYING IN VIENNA

On his arrival in Vienna, Beethoven took advantage of introductions provided by Waldstein and Haydn. Musical life still owed much to phenomenally rich patrons, a number of whom were to figure prominently in Beethoven’s life, such as the Lichnowskys, Archduke Rudolph (brother of Emperor Francis), and the Lobkowitz, Browne, Razumovsky and Kinsky families. Virtuoso performers, such as Beethoven, were much in demand in their drawing rooms.

Beethoven lived on the ground floor of the palace resided in by a connection of Waldstein’s, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, the aristocrat who had proved a substantial debt against the dying Mozart less than a year before.39 The Prince had his own string quartet, and organised regular musical salons, usually every Friday morning.40 It is sometimes speculated that his support for Beethoven was in response to pangs of conscience about his action against Mozart.

Beethoven was disappointed with his lessons with Haydn, who was preoccupied with his second visit to London and thinking of taking his pupil with him as copyist and factotum. As evidence of progress, Haydn sent the Elector some of his pupil’s pieces and requested reimbursement of money lent to him. The Elector’s response, based on a misunderstanding, was negative: most of the pieces, he said, were composed before Beethoven left Bonn; he suggested that Beethoven was not progressing, rather he was just ‘living it up’ running up debts, as he had done on his first trip to Vienna.41

Both pupil and patron were unfair to Haydn. He introduced Beethoven to Handel’s music and taught him counterpoint, the art of combining melodies. Like so many classical composers, he used the Gradus ad Parnassum of Johann Joseph Fux, a system for learning the style of great composers of the Renaissance, such as Palestrina and Lasso.42 This dry and dreary method was much approved of in Beethoven’s time, and indeed was still in use in the middle of the 20th century.43

Beethoven also took violin lessons three times a week from the leader of Lichnowsky’s string quartet. He studied more complex counterpoint with Albrechtsberger, the Kapellmeister at St Stephen’s.44 Up to around the turn of the century, he also studied with Salieri,* to whom he dedicated three violin sonatas.45

It was as a virtuoso pianist that Beethoven performed at the two annual concerts run by the Vienna Philharmonic Society. The piano, having been around since the pianos of Cristofori of Florence in the 1720s, had become more prominent at the beginning of the 1760s, the decade before the founding of the Philharmonic Society. The harpsichord, with its plucked strings suitable for the more intimate salon style, faded from view. The piano could make the larger sound needed in a hall; it could also hold its own against an orchestra, rather than having to alternate with it in separate blocks of sound. Beethoven exploited it to its technical limits at the time.**46

A couple of years after the death of Mozart, Beethoven was earning enough for his two brothers to leave Bonn and join him. Caspar came in 1794 as a music teacher, and Johann in the following year, as an assistant to an apothecary. The general exodus from the Rhineland included the Breuning brothers, and also Wegeler, who came in order to complete his medical studies, before returning in 1796 to settle with Eleonore von Breuning in Koblenz.

In November 1795, Beethoven was commissioned to compose the minuets and other dances for the charity ball held in the magnificent Redoutensaal in the Imperial Palace. He also played at an interlude during a performance of La Clemenza di Tito organised by Constanze Mozart. In 1796, he went on an extended tour, similar to that undertaken by Mozart some six years earlier. He visited Prague, Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin and, later in the year, Pressburg.

He taught, he advertised, and he sold his works. His Opus 1, a set of piano trios, was sold by subscription: 123 subscribers ordered 245 copies, which were printed by the leading publishing house, Artaria. From this, Beethoven made a profit of 735 florins, the equivalent of one year’s living expenses.47 Many of his works were commissioned. After six months elapsed, he was allowed to publish them himself and obtain a fee from publishers. He would seek simultaneous contracts in several countries at the same time.48

Beethoven was a good businessman, and proud of his ability to earn an income sufficient to live in comfort.49 From 1800 onwards, Lichnowsky granted him an annuity of 600 fl.* A couple of years later, Beethoven’s brother Caspar helped him with his business affairs, and managed to push up the prices demanded from publishers. Whereas Beethoven sold the First Symphony for 20 ducats, Caspar got 38 for the String Quintet. Caspar also started getting earlier works published, which contributed to the cash flow. But it was not always plain sailing. Copyright was a continual headache: in 1802, we find Beethoven putting a notice in the papers denying that quintets published by a publisher in Vienna and by one in Leipzig were the originals.**

THE FRUSTRATED COMPOSER AND LOVER

The First Symphony was performed on 2 April 1800 in a concert at the Burg theatre: tickets were available at Beethoven’s lodgings for a pro-gramme that also included a Mozart symphony, some extracts from Haydn’s Creation, one of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos, a Septet and an improvisation. It is hard for us to imagine the effect that this concert had. The audience would have been surprised by the opening of the symphony and by the increased, unusual, emphasis given to the wind instruments.51

So, by the turn of the century, when Beethoven was almost 30, he was well established. But he became increasingly temperamental. He bust up with Stephan von Breuning when they set up house together. His other Bonn friend Ferdinand Ries, whom he took in as a pupil, was horrified to find him fighting with his brothers in the street. To the composer and pianist Hummel, Beethoven wrote: ‘Keep away. You are false and fit for the knacker.’52 Later, he lost his temper when he was staying at Prince Lichnowsky’s opulent castle at Grätz.* The prince asked him to play to some French officers. Clutching the ‘Appassionata’ and the Razumovsky Quartets, Beethoven left in a huff, in the rain, to the nearby city of Troppau (now Opava).** On his return to Vienna, he smashed a bust of the prince.54 He patched up these quarrels and quickly made his peace. But there were other symptoms of his eccentricity. In 35 years, he lived in 33 lodgings,† 71 if one includes summer residences.

He would read deep into the night, letting candle wax drip onto the pages of his book, already blotched with coffee stains. The young Karl Czerny, today known for his volumes of piano exercises, climbed the many stairs to the fifth- or sixth-floor apartment in the Tiefen Graben to find Beethoven whose ‘coal black hair, cut à la Titus, bristled shaggily about his head. His beard – he had not shaved for several days – made the lower part of his already brown face still darker.’55

Beethoven would get up very early, at 5 or 6 am, and then he worked. After breakfast, he strolled in the fields beyond the old fortifications, in the Vienna woods or along the Danube. Although he was very much a loner, he was ‘always in love’, according to Wegeler. He was really crying out for affection. He sometimes attempted conquests ‘that an Adonis would have found difficult, if not impossible’. He fell for ladies who would have ruined themselves by falling for their music teacher. Despite the social changes, individuals were still expected to live and work within their divinely ordained class.†† Yet the temptations were considerable. An English colonel described the personal problems the male might feel: ‘Formerly when women wore long stiff stays and cork rumps, you might as well sit with your arm round an oaken tree with the bark on, as around a lady’s waist; but now, as you have seldom any more covering but your shift and gown of a cold day, your waist is extremely warm and comfortable to the feel.’57

Ries wrote: ‘Beethoven loved to see women, particularly pretty youthful faces.’58 We have already met his first love, Eleonore von Breuning. He proposed to the singer Magdalena Willmann during the 1790s, but she refused him, because ‘he was ugly and half crazy’.59 Neither of these reasons would appear to be an impediment to marriage, however.

In 1799, two young countesses, Therese and Josephine Brunsvik, became pupils, and Beethoven stayed on their family estate in Hungary. He fell for Josephine, but she then married Count Deym, who, following exile after a duel, returned to Vienna, where he ran a waxwork museum under the pseudonym Herr Müller. When Deym died, Beethoven fell in love again with Josephine. But it would have been unrealistic for them to marry: she would have lost her status, title and the guardianship of her children.60 By the time of her second marriage to Baron von Stackelberg, Beethoven’s affections had drifted elsewhere. In the intervening period, he had fallen for the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, a cousin of the Brunsviks, to whom he dedicated the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata. After she married a nobleman in 1803, Beethoven wistfully wrote: ‘I was loved by her, and more than her husband ever was. Yet he was more her lover than I.’61

Later, aged 40, he proposed to the eighteen-year-old Therese Malfatti. She was the niece of his doctor, and sister-in-law of his ‘secretary’ Gleichenstein. Apart from inspiring him to improve his wardrobe, the romance came to nothing.62

He fell for the irresponsible, brilliant conversationalist, Bettina Brentano, whose mother had been the model for one of Goethe’s characters in Werther. In her twenties, Bettina had chased the poet, by then almost 60. ‘I have got to have a child by Goethe at all costs,’ she exclaimed. ‘Why, it will be a demigod!’*64 Beethoven also fell for the guitar-playing Antonie Brentano, who had married Bettina’s half-brother, Franz. There were others as well.

One lady from this catalogue was presumably the ‘Immortal Beloved’ referred to in a letter written in July 1812, from Teplitz, where Beethoven had gone for a health cure.65 He wrote: ‘In bed, my thoughts are with you, my Beloved … you know my faithfulness to you; never can another possess my heart. Your love has made me one of the happiest and, at the same time, one of the unhappiest of men – at my age, I need a quiet steady life – is that possible in our situation? Ever thine, ever mine, ever each other’s.’66 Antonie Brentano is often the favourite candidate as addressee for this letter, which was found after Beethoven’s death in a secret drawer of a cash box.67

A great friend was Countess Marie von Erdödy, from one of the import ant families in the Hungarian aristocracy. She was described as ‘a very handsome, small, refined person five and twenty years old, who was married in her fifteenth year. Immediately after her first confinement, she contracted an incurable malady, so that, for ten years, with the exception of two or perhaps three months, she had been bedridden. Yet she gave birth to three dear healthy children who clung to her like creepers. Music is her sole enjoyment; she plays Beethoven’s compositions extremely well, and with swollen feet limps from one piano-forte to another, but for all that is cheerful and friendly.’68

THE REVOLUTIONARY CLIMATE AND NAPOLEON

In 1808, Beethoven lived in the same house as Countess Erdödy and her three children. But the countess was banished from Austria, for criticising the finance law of 1811. Banishments like this were not unusual in these unsettled times: the secret police were reputed to have 10,000 informers to assist in collecting information to pre-empt insurrection. Although actual policing seems to have been lax, the outspoken Beethoven might easily have found himself in gaol or banished.69 Beethoven was trailed, but he was only once arrested, because he was mistaken for a tramp.70 Possibly his friendship with the emperor’s youngest brother, Archduke Rudolph, gave him protection.

It is understandable that the authorities had for long been nervous. In the mid-1790s, the 27-year-old Napoleon was given command of the army of Italy. It did not take him long to move into Piedmont and on to Lombardy, the areas around Turin and Milan.71 After showing great personal bravery leading his troops over the bridge at Arcola, he marched into Austria in 1797, sending the court and no doubt the whole of Vienna into a considerable panic. But his supply lines became increasingly extended, so he stopped at Leoben, about 90 miles to the south. The nobility, bourg-eoisie, students and artisans offered themselves to defend the homeland. Beethoven wrote the ‘Austrian Warsong’ and the ‘Song of Farewell to the Citizens of Vienna’. Haydn wrote his Missa in Tempori Belli and offered to write a National Hymn. But Napoleon accepted peace, and the troops returned into Vienna in triumph as if they had actually fought and won. Under the subsequent Treaty of Campo Formio, the left bank of the Rhine went to France, and, as compensation for giving up Belgium, Austria was given Venice, once Napoleon had sent many of its treasures back to France.

General Bernadotte was appointed French Ambassador in Vienna, bringing in his retinue Rodolphe Kreutzer, to whom Beethoven dedicated the Kreutzer Sonata for Violin and Piano.72 At this stage in his career, the general flaunted his republican principles and Beethoven was a frequent visitor at the embassy.* According to a tale put about by Beethoven’s amanuensis and biographer Anton Schindler, Bernadotte encouraged him to write a symphony in honour of the Republic and its virtues. This eventually led to the ‘Eroica’ Symphony, although it was not finished until 1804, several years later.73

The Austrians reoccupied northern Italy briefly when Napoleon was in Egypt and Palestine. But French control was resumed following Napoleon’s victory at Marengo in June 1800. Six months later, following the battle of Hohenlinden, Beethoven took part in a concert organised in aid of wounded soldiers and was considerably peeved that his name did not appear in the advertisement. The French got to Melk, the magnificent Ben edictine abbey, high above the Danube, 50 miles from Vienna. Mozart’s sister Nannerl, living at St Gilgen just outside Salzburg, was in the war zone; her husband died while French soldiers were billeted on them.74

The situation was alarming. Since the Turks were defeated in 1683, Vienna had neglected its defences. The Habsburgs had to capitulate to Napoleon and this led to the Treaty of Lunéville in February 1801, under which the rest of Italy and the Rhineland passed into French control. Two years later, an imperial commission formalised the abolition of the ecclesiastical states, such as Cologne, and most of the lay principalities and free cities. Beethoven, however, had far greater anxieties on his mind.

DEAFNESS

As early as 1801, Beethoven was writing to friends: ‘My compositions bring me in a good deal; and I may say that I am offered more commissions than it is possible for me to carry out … so you see how pleasantly situated I am.’ The letter continued ominously: ‘But that jealous demon, my wretched health, has put a nasty spoke in my wheel; and it amounts to this, that for the last three years my hearing has become weaker and weaker.’75 His deafness started particularly in the left ear. He had written a few months earlier: ‘Only think that the noblest part of me, my sense of hearing, has become very weak. Already when you were with me, I noted traces of it, and I said nothing. Now it has become worse.’76 His doctors assured him that the complaint was temporary, and arose from an abdominal problem. He was apparently always suffering from diarrhoea: in 1797, a year of few compositions, he had been seriously ill.

He now took almond oil, cold and tepid baths, pills and infusions; his internal problems improved, but deafness persisted. He wrote to Wegeler: ‘the humming in my ears continues day and night without ceasing. I may truly say that my life is a wretched one … When at the theatre, I am obliged to lean forward close to the orchestra, in order to understand what is being said on the stage … Often I can scarcely hear anyone speaking to me; the tones yes, but not the actual words; yet, as soon as anyone shouts, it is unbearable.’ And again: ‘I cannot, it is true, deny that the humming, with which my deafness actually began, has become somewhat weaker, especially in the left ear. My hearing however has not in the least improved; I really am not quite sure whether it has not become worse.’77

Some have attributed his deafness to syphilis. They point to his contemporary, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya who went stone deaf in 1792, and suffered from syphilis.78 And they refer to Beethoven’s earlier writings, such as: ‘Keep away from rotten fortresses, for an attack from them is more deadly than one from well-preserved ones.’79 From Prague, he had written to his brother: ‘Do be on your guard against the whole tribe of bad women.’80

It is generally agreed, however, that he suffered from otosclerosis,* and the subsequent deterioration of the auditory nerves. For long, he used the brass ear trumpets such as those which can be seen in the Beethoven museum in Bonn. Deafness became total around 1818, when anyone communicating with him had to write down their remarks in a book. These are called the ‘conversation books’. One hundred and thirty-seven of them survive. 82

Like many other reasonably affluent Viennese, Beethoven spent part of the summer months in the country, staying in several different places, all now on the outskirts of Vienna. These included Baden, the spa enjoyed by Constanze Mozart, and Unterdöbling, Oberdöbling, Mödling, delightful places at the foot of the Vienna Woods, among trees and gardens full of birds. In 1802, he stayed in a small two-storey house amongst the woods and vines of Heiligenstadt, now to be found in a narrow street. He stayed for longer than usual, working on piano sonatas, and the Second Symphony. There, in October 1802, he poured his heart out in a letter of despair to his two brothers. This indicates that he had been troubled for the last six years by ‘an incurable complaint, which has been aggravated by incompetent doctors. I cannot enjoy meeting people, talking to them, exchanging ideas with them. I can only risk meeting them when absolutely necessary, because I am so desperately worried that they will notice my condition. So I am condemned to a lonely existence, almost that of an outcast … It has driven me to despair, even to the point of contemplating sui-cide. Only art held me back. So, Death, I look forward with Joy to meeting you. Come when you will; I will face you courageously.’ He continues: ‘Yes, I must now completely abandon the fond hope which I brought here that I would at least see some improvement. It has gone, withered like the leaves in autumn.’ He asks providence to grant him a single day of Joy.83

This ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’ provided an emotional outlet for Beethoven and, thereafter, he was far less prone to self-pity and despair. Within eight days of it, after his return to Vienna, he was writing business letters to the publishers Breitkopf & Härtel about two sets of variations for the piano that he had composed.84

He went to the top Viennese doctors, including the staff surgeon to the emperor.85 He considered trying miraculous cures through the use of Galvanism, named after Luigi Galvani who had observed what he called animal electricity in frogs’ legs. For a few years, Beethoven tried a faith healer at St Stephen’s, who prescribed pouring oil into the ears. This was at the time he was visited by the young Czerny who recorded that he ‘had cotton, which seemed to have been steeped in a yellowish liquid, in his ears. At the same time, however, he did not give the least evidence of deafness.’86

Indeed, at first, his hearing got no worse. He launched into what is regarded as his ‘middle’ period,* 1803–12, years of astonishing creativity. In 1806, he was composing at the rate of one major work per month. These years heard the Third Symphony, and ended with the completion of the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies. They heard the Violin Concerto – the score was only just ready with two days to spare and the soloist more or less sight-read his part, interpolating some violin acrobatics of his own between the movements. They heard the ‘Appassionata’ and ‘Waldstein’ Sonatas, the Razumovsky Quartets, the overtures to Coriolan and Egmont.88

Beethoven worked on the Third Symphony when staying in a small farmhouse very close to the one in Heiligenstadt where he had despaired. The small white building with a tiny courtyard covered in vines provides a strong contrast to Prince Lobkowitz’s palace with its magnificent staircase leading up to the grand saloon, in which the ‘Eroica’ was given a first, private run-through in December 1804. The symphony was not received too well at its first public performance on 7 April 1805: a man shouted from the gallery: ‘I’ll give another kreutzer if only the thing will stop.’89 Had that man possessed modern equipment which allows one to play Mozart’s last three symphonies, themselves masterpieces, and then listen to the ‘Eroica’ written only fifteen years later, he would have understood the significance of the occasion. The symphony has been called ‘one of the incomprehensible deeds in art and letters, the greatest single step made by an individual composer in the history of the symphony and in the history of music in general’.90 Another writer has described it as ‘one of the wonders of music, supremely alive in every detail yet completely unified, supremely clear yet most powerfully impulsive’.91

The Third Symphony was first dedicated to Napoleon. But Beethoven was furious when Napoleon declared himself Emperor of the French in May 1804. He ripped out the reference to ‘Buonaparte’, although he later reinstated it. By the time of the first printed edition, the symphony had been called ‘Eroica’, and dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz, who paid Beethoven a large sum for both the dedication and the exclusive rights to it for six months.92

Early in 1803, Beethoven had taken lodgings in Emanuel Schikaneder’s Theatre an der Wien, where he was appointed composer to the theatre. Taking advantage of the choral resources, and possibly inspired by his own sufferings, he wrote the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives. Being essentially an instrumental composer, he first took advice from Salieri about vocal declamation.

Schikaneder wanted a new opera. The proposed work, Vesta’s Feuer, proceeded slowly and was abandoned. Operas by the Paris-based composers Luigi Cherubini and Etienne-Nicolas Méhul, with their plots of heroism, rescue and escape, had been successful in Vienna. So Beethoven turned to a French work,* Bouilly’s Léonore, ou l’Amour Conjugal. The story of Léonore, the ideal woman, suited Beethoven; Florestan, her husband whom she saves, seems to encapsulate Beethoven’s own suffering. This would eventually become the opera we know as Fidelio.93

NAPOLEON AGAIN: AUSTERLITZ

The dire political and military situation provided a chaotic background to this. The Habsburgs were very concerned that they were being lined up to become the next of Napoleon’s puppet states, like those in Germany, Italy and Spain, so they concluded a defensive pact with Russia. War broke out again; Beethoven’s friend Ries was ‘compelled to shoulder a musket in this calamitous war’.94 After a catastrophic surrender of the Austrian army at Ulm, Napoleon triumphantly entered Vienna in the second week of November 1805, just three weeks after the French naval defeat at Trafalgar. He stayed in Schönbrunn; but he did not relax. He had to protect himself from the approaching allied armies from Russia and Italy. It helped that he was facing ‘a squabbling committee consisting of two sovereigns and their advisers’.95

By luring the Russians to attack him on 1 December 1805, before the arrival of the Austrian reinforcements from Italy, Napoleon won a decisive victory at Austerlitz, on the estate of Prince Kaunitz just outside Brünn (now Brno) in southern Moravia. Austerlitz was Napoleon’s ‘supreme professional performance’.96 The French lost 8,000 men killed or wounded; on the allied side, 12,000 were killed and wounded, 150,000 prisoners and 133 guns were taken. ‘This is the happiest day of my life’,97 said Napoleon after the battle, a remark which, one may conjecture, might be intelligible to someone with a military training. Talleyrand, the ubiquitous and obsequious French politician, crippled by falling out of a chest of drawers aged four, told him: ‘Your Majesty can now eliminate the Austrian monarchy or re-establish it. But this conglomeration of states must stay together. It is absolutely indispensable for the future well-being of the civilised world.’98 However, the thousand-year Holy Roman Empire was brought to an end.*

The first performance of Fidelio took place at the Theater an der Wien less than a fortnight before Austerlitz. Beethoven’s patrons had fled, so it played to almost empty houses. It ran for only three nights and got bad reviews. Besides, an opera about oppression and political prisoners was untimely. A revised version in 1806 was poorly performed and failed also. Beethoven’s ‘propensity for writing long-drawn-out movements, which served him well in instrumental music, militated against him in a stage drama’.100 In 1807, he applied for a permanent position as an opera composer, but was rejected. Perhaps it was just as well: his skill was at its best in instrumental and choral music, not opera.

Meanwhile, Beethoven had to live through the food shortage caused by the arrival of a vast French army. There were food riots. The cost of the war was enormous, paper money rolled off the printing presses, and the state debt increased, aggravated by the French, who spread around counterfeit banknotes. The cost of living had nearly trebled in just four years. People on fixed incomes, such as government employees, were particularly badly hit. One police report estimated that only one in five petty officials could afford to buy meat for their families. Others profiteered: the peasants and agrarian population benefited from land and grain price increases, especially those who had commuted their feudal obligations (‘robot’) into fixed liabilities, or who had borrowed. Industrial expansion, the manufacture of uniforms for the army and the blockade of Europe provided a huge captive market for some.101

Beethoven was conscious of the need for hard currency in concluding his business dealings. In 1806, he wrote to a publisher: ‘I expect you to offer me £100 sterling, or 200 Vienna ducats in gold, and not in Vienna bank-notes, which under present circumstances entail too great a loss.’102 He thought of accepting the position of Kapellmeister in Kassel, at the court of Jerome Bonaparte, King of Westphalia. This offer enabled him to negotiate a guaranteed annuity of 4,000 fl from his leading patrons. Archbishop Rudolph contributed 1,500 fl, Prince Lobkowitz 700 fl, and Prince Kinsky, a new and less reliable donor, the considerable sum of 1,800 fl.103 This arrangement, whereby the nobility paid for him to be independent, was unprecedented.104 There were some strings attached: almost twenty years later, Beethoven was giving Archduke Rudolph two-hour lessons each day. But the archduke was a magnificent patron; Beethoven dedicated to him the ‘Emperor’ Concerto, the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, the Missa Solemnis and the ‘Archduke’ Trio.

With his increasing deafness, Beethoven continued to be obsessed with financial security. He was right: there was continuing inflation; and, after Kinsky was killed in a riding accident and Lobkowitz died, there were arguments with their heirs who wanted to cancel the annuity. Beethoven did not feel that it was in any sense assured.105

The flow of major compositions continued. A benefit concert on 22 December 1808 has been described as being surely ‘one of the most fantastic displays of new music ever put on by a single composer’.106 It included the first performance of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, movements from the Mass in C and the Fantasy for Piano, Orchestra and Chorus. The ‘Emperor’ Concerto was written in the following year, but, owing to his deafness, Beethoven did not perform it himself.*

NAPOLEON AGAIN: WAGRAM

Beethoven must have been horrified when hostilities were resumed yet again. When the French invaded Portugal in 1807, the emperor’s brother Archduke Charles, a competent commander-in-chief and one of the more perspicacious members of the royal family,107 summed up Napoleon’s aims: ‘There can no longer be any question what Napoleon wants – he wants everything.’108 Intelligence reports from the ambassador in Paris, Clemens von Metternich,* indicated that Napoleon’s continuing aggression was inspiring some opposition at a high level in the French government. So, plans for war began to be drawn up in May 1808. The Tyrolean peasantry successfully rose against the Bavarians, whom Napoleon had installed as their overlords. But, in the event, Napoleon crushed Spain and returned to Paris to suppress the opposition. On 14 April 1809, he left Paris to wage war against Austria for the fourth time.

Vienna was bombarded on the night of 11 May (see colour plate 4). Beethoven took refuge in his brother Caspar’s house, covering his head with pillows. The city fell on 13 May; a fortnight later, Haydn died. Beethoven wrote: ‘What a destructive disorderly life I see and hear around me: nothing but drums, cannons, and human misery in every form.’110 It seemed that the Viennese were accepting that the French would take over; one observer reported that the eagerness with which the city’s women rushed to accommodate the French soldiers ‘made Vienna look like Sodom and Gomorrah’.111

Napoleon needed to destroy the Habsburg army led by Archduke Charles before he could afford to relax in the palace at Schönbrunn. In early July 1809, he decided to cross the Danube, six miles south of Vienna. When a small number of his soldiers were across, the archduke attacked and sent boats down to destroy his pontoon bridge, which was also hit by a tidal wave of flood water. The battle of Aspern, his first battlefield defeat, has been described as Napoleon’s ‘rashest military undertaking thus far; an act of recklessly bad generalship’.**113 But the archduke, possibly fearing that a single defeat could destroy the Habsburg dynasty, did not pursue his advantage; Napoleon took the rest of his army across the Danube. On the battlefield of Wagram, he faced more than 300,000 men and nearly 900 cannon. After a two-day battle, at least 32,000 of Napoleon’s own troops and roughly a similar number of Austrians lay dead or wounded on the field. It has been said that Wagram ‘proclaimed a new order of warfare; it looked ahead to such combinations of massed manpower and firepower as the battles of the American Civil War; as Verdun and the Somme; as Stalingrad’.114

And so the war ended again, for the moment. Emperor Francis ceded further lands, this time in Poland and along the Adriatic. Napoleon, anxious for an heir, married the emperor’s daughter Marie Louise, a union arranged by Metternich, who had recently become foreign minister and now dominated the Habsburg Empire.115 But first, Napoleon took up residence again in Schönbrunn, running his empire from there during the summer, and proving his virility by siring a child* on his Polish mistress Marie Walewska.

Conditions in Vienna were wretched and the burden of billeting the enormous army was considerable; sometimes 100 or more soldiers were required to be accommodated in one house. While the French were in occupation, there was very little food, and the Viennese ate bread made of barley left over from the breweries. Minor comforts such as tea and coffee could not be obtained.117

The government was forced to declare its first bankruptcy, by means of the finance patent of 15 March 1811: the nominal value of the florin was reduced to one-fifth of its previous value. Hence Beethoven’s annuity of 4,000 fl reduced to 800 fl. The bankruptcy led to a highly complicated situation where two currencies were operating at the same time.118

Later, in September, the government decreed that contracts in fixed money should be divided by 2.48 rather than 5, making Beethoven’s annuity 1,600 fl. It is no wonder that sponsors such as Lobkowitz and Kinsky, who were feeling the pinch, tried at first to pay him in the reduced currency. Eventually they settled for an annuity at 3,400 fl.**120

CONGRESS OF VIENNA

In one of the most famous campaigns in modern history, Napoleon was repelled from Russia, losing 570,000 men in the process. It was an exceptionally cold winter. He arrived at the Tuileries just before midnight on 18 December 1812, having travelled virtually non-stop, apart from several breakdowns, 1,400 miles in 13 days. With extraordinary energy, he raised a fresh army and, by April, he had 200,000 men in the field. He defeated the Russians and Prussians at Lützen and Bautzen. In August, the Habsburgs declared war, and Napoleon suffered a serious defeat at a four-day battle around Leipzig in October.* On the morning of 1 April 1814, the allied cavalry, commanded by the tsar, rode 30 abreast down the Champs Elysées, the first foreign armies to enter Paris since the 15th century. The Comte de Provence was installed as King Louis XVIII.** The Congress of Vienna, presided over by Metternich, began in October: its main objective was to settle territorial claims in the post-war period, with a view to maintaining the balance of power.121

Shortly before this, Beethoven worked with Maelzel, who had recently invented the metronome, to arrange a grand charity concert in aid of war victims; fundraising concerts, sometimes organised by a group of ladies, had begun about this time. Beethoven’s ‘Battle’ Symphony, which celebrated Wellington’s victory over Napoleon at Vittoria, was performed on a star-studded stage, which included Hummel, Salieri and the virtuoso violinist and composer Louis Spohr. Its success with the Viennese was ‘stupendous’ and it was given four performances in quick succession. This brought Beethoven considerable financial gain, and led to a bitter quarrel with Maelzel about the future rights to the work. An embarrassing amalgam of ‘Rule Britannia’, ‘God Save the King’ and so on, the ‘Battle’ Sym-phony thankfully only lasts about a quarter of an hour.122

Heads of five reigning dynasties and of 216 princely families flocked to Vienna, ‘like peasants to a country fair’, as Marshal Blücher (of Prussia and, nine months later, of Waterloo) put it.123 Beethoven will have seen the Prater amusement park full of riders and carriages. The protagonists were Tsar Alexander, of whom Napoleon said that ‘it would be difficult to have more intelligence than the Emperor Alexander; but there is a piece missing; I have never managed to discover what it is’.124 There was the French minister, the unprincipled Talleyrand,* the Habsburg chancellor Metternich and the British Lord Castlereagh.** With them, there was an enormous influx of hangers-on. All interests were represented, down to a Herr Cotta of Augsburg, representing the publishing trade.126 Mendelssohn’s uncle was in the Prussian delegation.

Every night, dinner was laid at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna for 40 tables, and while the delegates were dining or carousing, there was a lot of rummaging in wastepaper baskets by housemaids. Baron Hager, the director of the state police, had covered the whole city with his network, and used this material to submit his voluminous reports to the emperor.127 Most of the diplomatic couriers were in Austrian pay and all letters were opened and transcribed. ‘The interception of letters remained a craft in which the Austrians had no equals.’128

As happens at conferences, a festival committee devised a varied programme of entertainment to distract the participants from the futility of their presence and also, in this case, from the activities of the housemaids. ‘At times it seems that no other committee at the Congress worked so hard.’129 For the VIPs, there was Metternich’s masked ball, at which Lady Castlereagh wore in her hair her husband’s garter (the strap normally worn below the knee, signifying the highest order of chivalry in England). The Castlereaghs had availed themselves of dancing lessons, but it was observed ‘how sadly each of them had profited by such instructions’.130

There was an unending sequence of drawing rooms, balls, banquets and gala performances. Waltzes were all the rage. There were tableaux vivants at which the young ladies of Viennese society would give representations of Louis XIV at the feet of Madame de la Vallière, or Hippolytus defending his virtue before Theseus. There were sleighing expeditions to the Vienna Woods; there were hunting parties and there was Kraskowitz’s balloon ascent. The ballet Fore et Zephire was performed again and again at the Opera House with Signorina Bitottini in the principal part. On 28 October, there was a performance of Fidelio, which Beethoven had revised in the spring, using another librettist. On a weekday, instead of a Sunday, out of respect for the religious prejudices of the British delegation, the tsar and Frederick William attended a gala concert of the Seventh Symphony and the ‘Battle’ Symphony. Beethoven conducted, ‘a short and stout figure waving his baton triumphantly’.131Fidelio was repeated fifteen times. Beethoven wrote several works specifically for the Congress, such as a cantata, ‘The Glorious Moment’, and a ‘Chorus for the Allied Princes’.132

There were other diversions. The Castlereaghs continued to cause some amusement. Sometimes, it was the way they went window-shopping ‘like a provincial on holiday’; on other occasions, it was their bourgeois domesticity, and their tendency to sing Anglican hymns in their house, to the accompaniment of a harmonium.133 Others were more typical, according to the police reports. The King of Prussia went out in civilian clothes with a round hat pulled down over his eyes. The Grand Duke of Baden spent his nights in a brothel. The Prince de Ligne, in his 80th year, died from a cold contracted while waiting for an assignation at a street corner. The tsar and Prince Metternich swapped mistresses. A report to the emperor also states that a certain Mayer made his living by selling remedies against vene-r eal disease.134 What Emperor Francis made of all this detail, one cannot imagine: he was normally at his happiest ‘when engaged in his workshop stamping seals onto sealing wax or merely cooking toffee at the stove’.135

The Congress was concerned about Russian expansion westwards and became bogged down over the partition of Poland, the country of the five-year-old Frédéric Chopin.136 Then, proceedings stopped when Napoleon escaped from Elba. Although Napoleon landed on 1 March, Metternich only opened the packet from the consul in Genoa at 7.30 am on 7 March. Vienna emptied: ‘A thousand candles seemed in a single instant to have been extinguished.’137 It was observed that ‘fear was predominant in all the Imperial and Royal personages’.138

BESET WITH PROBLEMS

The ‘Battle’ Symphony was composed at a low point in Beethoven’s creative life. After 1812, his ‘torrent of inspiration dwindled to a trickle’.139 The pressures on him were considerable. He wrote to Archduke Rudolph: ‘I have been ailing, although mentally, it is true, more than physically.’140 Also, his popularity began to decline after around 1815. And the waltz, with its energy, speed and human contact, was superseding group dances such as the stately and stationary minuet as the fashionable music.* Vienna now vibrated with music of a totally different variety to Beethoven’s. As early as 1809, a German journalist noted that every evening 50,000 thronged to dance halls and calculated that one in four of the Viennese must have spent their evening waltzing.141 The title of an anthology of dances published fifteen years later, Halt’s enk z’samm (‘Hold on tight’), tells us much about the nature of the dancing of the time.142

Artistically, Beethoven was out on a limb. In June 1816, Salieri celebrated the 50th anniversary of his arrival in Vienna with a public service in the cathedral, the award of a gold medal and an evening party at which his pupils, old and young, including Schubert, each made a contribution. Salieri gave his impressions of the reception: he praised the ‘expression of pure nature, free of all eccentricities’ in the works of his pupils, but he deprecated the extravagance and disregard of conventional forms for which ‘one of our greatest German artists’ was responsible.143 By this, he meant Beethoven.

Although 1816 heard the song cycle An die Ferne Geliebte, there was a sharp decline in Beethoven’s musical productivity in the following year: it is thought that he may have had some sort of debilitating illness. Certainly, his hearing deteriorated, so much that soon he was using the conversation books for people to write messages for him. At times, he was ‘in the most deplorable condition’144 and so ill-kept and unhygienic that guests at an inn avoided sitting near him.

Family problems were added to the professional, financial and health worries. In 1812, he forced his brother Johann, a successful pharmacist in Linz, to marry the woman he was living with. She already had an illegitimate daughter by another man. Then, in November 1815, Caspar died of tuberculosis, leaving behind his wife Johanna, daughter of a well-to-do upholsterer, and their nine-year-old son Karl (see colour plate 14). A codicil to the will appointed Johanna as guardian, with precedence over Beethoven. Beethoven was obviously desperate for a child of his own, and Karl fitted the bill. His only chance of getting custody was to prove Johanna’s unsuitability. So, he alleged that she had poisoned her husband, and he dragged up a four-year-old case in which she had been detained for stealing pearls.145

Johanna was also rumoured to have offered herself ‘for hire’. Beethoven wrote: ‘Last night this “Queen of the Night” was at the artists ball till 3 o’clock, not only wanting in sense but even in decency … Oh terrible, and into these hands ought we, even for a moment, to entrust our precious treasure? No, certainly not.’146 Karl was whisked off to a boarding school on the outskirts of Vienna. Beethoven wrote to his schoolmaster asking him not to allow Karl’s mother to exert any influence over the boy.147

In 1818, Johanna began interfering in Karl’s education, which was strict and severe, although possibly no more than was customary. At the end of that year, Karl ran away to her. There was a court hearing about the boy’s future. Beethoven attempted to have the case heard in the court for the nobility because he was ‘van Beethoven’.* Johanna appealed on the grounds that van Beethoven was a commoner and, to his chagrin, won. She was granted temporary custody, having claimed that Beethoven’s deafness and poor health made him an unsuitable guardian. Beethoven attempted to have Karl sent to a top school in Bavaria, but the magistrate turned that down. The case dragged on, with Beethoven eventually winning in 1820 after four and a half years, around the time Johanna produced an illegitimate daughter, an event which may not have been so unusual given that 40 per cent of births in Vienna at that time were illegitimate.149

Apart from the emotional strain, the court case took up much of Beethoven’s time: for the appeal, he had to prepare a memorandum 48 pages long.150 And he was totally unsuitable as a surrogate father for a child of Karl’s age, even if he tried very hard. We see him writing to the schoolmaster that Karl’s ‘boots are too narrow’, and added that ‘a thing of that sort spoils the feet, so I beg you not to let him put on these boots any more until they have been stretched. As regards pianoforte practice, I beg you to keep him to his work, otherwise there is no use in him having a teacher.’151

A source of great practical and moral support to Beethoven, almost a mother figure, during these difficult years, was Nanette Streicher.* Some extracts from his letters to her indicate the tedious and intractable problems he faced, or thought he faced, with his domestics. ‘The low behaviour of these persons [the two servants Nany and Baberl] is unbearable … for a housekeeper she has not sufficient training … the other does not really deserve a New Year’s present.’ And again, ‘I have already found out that she [i.e. the cook] cannot cook daintily, nor in a way beneficial to health. She behaved at once very pertly when told about it, but in the sweetest manner I told her that she should pay more attention to it. I did not trouble any more about her, went for a walk in the evening, and on my return found she had gone, leaving this letter behind. As this is leaving without giving notice, the police perhaps will know how to make her return.’ On another occasion, he wrote to Nanette: ‘Concerning the future housekeeper, I wish to know whether she has a bed and bedroom furniture? By bed, I mean partly the bedstead, partly the bed, the mattresses etc etc.’154

Laundry seems to have been a particular obsession. He wrote to Nanette: ‘I beg you only to say to him that you thought that a pair of socks has been lost, this is clear from the letter which you wrote to me about it; he is always telling me that you had found the socks again. The washerwoman received two pairs of stockings, as the two washing bills, yours and mine, showed; and this would not be so had she not received them. So I am convinced that she gave him the two pairs of stockings, as she certainly received them, so that they must have got lost only through him.’ Again Beethoven writes: ‘I also ask you kindly to see that the washerwoman delivers the washing at latest Sunday. I do not wish you to imagine that I think that in any way through carelessness on your part anything has been lost … I must have cooking for myself, for in these bad times there are so few people in the country that it is difficult to get a meal in the inns, still more to find what is beneficial and good for me.’ He adds: ‘I beg you to send to the washerwoman so that the washing may come home on Sunday.’155

That this genius was being diverted by such trivia is amazing. Beethoven must have been completely distracted. At least there is an occasional glimmer of humour. ‘Yes, indeed all this housekeeping is still without keeping and much resembles an allegro di confusione.’156

There was ‘business’ correspondence to be attended to as well, whether writing to George Thomson of Edinburgh, for whom he arranged many Scottish, Welsh and Irish airs,* or to publishers about corrections to proofs. ‘Frequently the dots are wrongly placed, instead of after a note, somewhere else’, he wrote to Schotts in Mainz. ‘Please tell the printer to take care and put all such dots near the note, and in a line with it.’158 For all his slovenly appearance, his personal habits and the chaotic appearance of many of his autographs, Beethoven showed a meticulous attention to detail.

THE LAST GREAT WORKS

At the end of the decade, Beethoven’s output picked up, and the quality improved. He started work on the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, his first major project for many years. Shortly before he completed it, he received a Broadwood piano from London, where Clementi had been publishing his works. Now that war was over, several attempts were made to get Beethoven to visit London. He contemplated rearranging the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata to make it suitable for an English market, an interesting notion. A visit was planned for early 1818. But health and the problems with Karl seem to have got in the way.

In 1819 he started work on the ‘Diabelli’ Variations. The publisher and composer Diabelli had circulated a waltz theme to 50 or more composers around Vienna, including Schubert, Liszt, Czerny and Hummel, inviting them to submit a variation which would be combined into a ‘union of artists of the Fatherland’. Beethoven naturally did not want to take part in a collective work, and in any case he thought the theme trivial. He eventually produced his own complete work with 33 variations.159

Also in 1819 he began the Missa Solemnis, which was intended for Archduke Rudolph’s installation as Archbishop of Olmütz in the following year. Beethoven decided to postpone printing the work, and to sell copies to the principal courts of Europe and to anyone else who might subscribe. This naturally entailed considerable correspondence, the canvassing of sponsors, letters to Goethe asking him to use his influence with the Duke of Weimar, and so on.

In the early 1820s he wrote the last three Piano Sonatas. But there was a pause in 1821, which coincided with bereavement and personal problems. His much-loved Josephine Stackelberg (née Brunsvik) died.160 Also Beethoven seems to have had rheumatic fever and jaundice.161 The doctors at least got him to reduce his consumption to one bottle of wine a meal.162

Around 1822, he was requested to write an oratorio for the Boston Musical Society. Prince Galitzine of St Petersburg commissioned some quartets; the London Philharmonic Society commissioned a symphony. He wrote to his friend in London, Ferdinand Ries: ‘If only God will restore me to my health, which to say the least has improved, I could do myself justice, in accepting offers from all cities in Europe, yes, even North America, and I might still prosper.’163 The Almighty ensured that the flow of masterpieces continued. In 1824, the Ninth Symphony was performed. In 1825–6 he wrote the Grosse Fuge and the final String Quartets.

Meanwhile, Karl helped his uncle with messages and accounts. He stayed with him at Baden, one of Beethoven’s favourite country retreats, in summer 1823, and in Vienna during his university studies. But they quarrelled. Beethoven wrote in October 1825: ‘My dear son! Only nothing further – only come to my arms, you shall hear no harsh word. For heaven’s sake do not rush to destruction – you will be received as ever with affection – as to considering what is to be done in future … no reproaches, on my word of honour, for it would be of no use.’164 At the end of the following July, Karl tried to shoot himself in the head at Helenenthal, a lovely beauty spot near Baden.* Karl blamed his attempted suicide on his uncle. Beethoven was appalled at the disgrace, and at the crime of suicide, particularly as it was a step he himself had struggled to resist taking. After being released from the city hospital, Karl joined the army.165

NEW STYLES – ROSSINI AND WEBER

Beethoven’s successors found his late works very difficult to understand. For Berlioz, Mendelssohn and Schumann, the influential works of Beethoven were the ‘Eroica’, ‘Pastoral’ and Fifth Symphonies, and the Sonatas Opus 53 and Opus 57. Most of the later works were received ‘with disappointment and embarrassment, even by those who admired the composer and put forward the excuse of his deafness’.166 ‘If only we knew what you were thinking about in your music’, the poet Grillparzer confessed to him in 1823.167 The string quartet, the Grosse Fuge, is a good example: after its first performance in March 1826, it was not heard again in Vienna for 33 years.

Carl Maria von Weber at work

While Beethoven was conceiving his great final works, new trends and new styles continued to develop, especially in opera. The first performance of Rossini’s Barber of Seville, regarded by some as perhaps the greatest of all comic operas, had taken place in 1816. In 1822, there was a Rossini festival in Vienna, in which six operas were performed with considerable commercial success. Rossini ‘fever’ raged.168 Also around this time, Carl Maria von Weber was transforming opera, orchestral performance and orchestration. We will meet Rossini again in a later chapter. Here, something should be said about Weber, who, with Beethoven, would exercise such a consider able influence on composers in the 19th century.

Weber visited Beethoven in 1823, when he came to Vienna for the first performance of Euryanthe, an opera which provided much inspiration for Wagner.169 Weber, like Beethoven, was one of the most brilliant piano virtuosos of his age:* his concert pieces such as the Invitation to the Dance inspired both Liszt and Chopin.

Weber was a cousin of Constanze Mozart. Although small and with a limp, he was a formidable opera director. At work in Breslau, Stuttgart, Prague and Dresden, he implemented proper conditions of service, got rid of older players, improved the repertoire and revised rehearsal arrangements. There was uproar,** manifestos and open letters were issued; but he even went so far as to learn Czech, so as to be able to understand the grumbles. He paid great attention to detail, casting, production and lighting. He studied costume designs from old books and he himself supervised the scenery painting.170

Weber also transformed conducting methods. The Dresden orchestra was still seated in much the same way as it was in Hasse’s time, when the conductor sat at the clavier in the middle, unable to see some of the players, a few of whom were peering at the music over his shoulder. Weber conducted from the front. We see this in the well-known picture of him conducting the orchestra in London, directing with a rolled up sheaf of paper. This was something entirely new.†172

Comparing Weber’s operas with, say, the Fidelio of fifteen years earlier makes one appreciate the speed of change, both in content and in the use of instruments to create colour, whether individually or together. Der Freischütz was first performed in Berlin in June 1821. A contemporary described it evoking ‘unbridled and hysterical enthusiasm’.173 Critics and jealous competitors, such as Spontini and Spohr, dismissed it as pop-opera for the masses. But, here was a truly German opera, the successor to the ‘Singspiel’ – opera with vernacular and music mixed, as in Mozart’s Die Entführung and The Magic Flute.

It is based on the German folklore and country life in which, as a young man, Weber had immersed himself: he was one of the first composers to realise the potential of folk melody as a source of inspiration. There are jolly drinking and hunting choruses, lovely arias, and the Wolf ’s Glen scene, which is weird, phantasmagoric and reminiscent of Macbeth. For this, Weber insisted on having an ‘owl with flaming eyes, and real fluttering bats’. ‘Spare neither spectres nor skeletons’, he wrote, ‘and let the horrors increase crescendo with each bullet.’174

For the intellectuals, the mystery, superstition, legend and ghosts, and the emphasis on Nature, fitted in with the Romantic movement which was sweeping away Classicism. And ordinary people, such as soldiers returned from the Napoleonic Wars, ‘imbued with the newly won pride of German patriotism’, related easily to the ordinary humble village folk, ‘the breeze of the German forests and mountains’, and ‘the horns and popping muskets of the huntsmen’.175

There were at least 30 different productions of Der Freischütz by the end of 1822. At one time during 1824, there were three productions running simultaneously in London, and there was one in New York in the following year.176

Weber’s Euryanthe is a colourful tale of knighthood and romance. There are the choruses, like the Huntsmen’s and Peasants’ choruses; there is vengeance worthy of Otello; there are luscious and lyrical songs such as Euryanthe’s ‘Tinkling bells in the glen, the rippling brook’. But it was not a success at the time, partly because of the Rossini craze with which it coincided.

Then, at the start of Oberon, we seem to look through gauze, it is so light and fairy-like. The playbill described it as ‘Oberon, or The Elf-King’s Oath; with entirely new Music, Scenery, machinery, Dresses and Decorations’. It is very different from the others, almost a play punctuated by occasional music. The colour of the music is delightful, colour which only someone who totally understood the workings of an orchestra could reproduce.

In all three operas, Weber had created a new style of orchestration. Thus these works are landmarks; just as much as Beethoven’s great works of the time. Debussy said that Weber ‘scrutinises the soul of each instrument and exposes it with a gentle hand’.177 Beethoven recognised that this was something new. He said of Weber and Der Freischütz: ‘that usually feeble little man – I’d never have thought it of him.’*178

BEETHOVEN – TOWARDS THE END

All this was happening at a time when Beethoven was considered completely eccentric. He could communicate solely by means of the conversation books. But in spite of all this, a journalist could say in 1822 that he ‘radiated a truly childlike amiability … even his barking tirades … were only explosions of his fanciful imagination and his momentary excitement. They were uttered without any haughtiness, without any feeling of bitterness or resentment.’179

There was a disastrous rehearsal of Fidelio in 1822, at which the orchestra broke down completely; his amanuensis and faithful secretary Schindler persuaded him to abandon and return home. On the other hand, in May 1824, there was a historic concert at the Kärntnertor theatre at which the Ninth Symphony, the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei from the Missa Solemnis and the overture, ‘The Consecration of the House’, were performed. Beethoven had to be turned round to witness the applause which he could not hear. Yet, even this occasion went sour: the financial outcome was not so good owing to the heavy expenses, and there was a row in public, when Beethoven accused Schindler of cheating him. Besides, Beethoven had had a struggle with the censors who maintained that the excerpts from the Mass should not be performed in a concert.

In 1826, Beethoven started work on a Tenth Symphony. After having had a genuine attempt at reconciliation with Karl, there was a further row. In December 1826, he visited his brother at Gneixendorf, along the Danube towards Melk; on the return journey, he caught pneumonia. ‘I have been prostrated with the dropsy since the 3rd December’, he recorded.180 Dr Malfatti was called in, among other doctors, and prescribed iced punch. Beethoven wrote to London about a possible benefit concert: he was still, but unnecessarily, concerned about his finances.* The London Philharmonic Society sent him £100 through Rothschilds, and he asked Schindler to write and thank them for it. Schindler wrote: ‘Even on the brink of the grave he thanked the Society and the whole English nation for the great gift.’182 Beethoven wrote to the publishers Schotts at Mainz asking for some Rhine or Moselle wine which Dr Malfatti had prescribed. But it did not arrive until he was dying: ‘Pity, Pity, too late’, he commented. These seem to be some of his last words.183

He died, probably of cirrhosis of the liver,184 on 26 March 1827, at a quarter to six in the evening. Ironically, the only actual witness at his death was Johanna, ‘The Queen of the Night’.** An acquaintance of Schubert’s viewed the body on the following day. It was in a room almost unfurnished apart from the six-octave Broadwood grand piano which the English had sent him, and a coffin. The acquaintance, who was with a friend, noticed that the smell of corruption was already very strong. They asked for a lock from Beethoven’s head, but the attendant had to wait until three fops, tapping their canes on their pantaloons, had left; and, after he had been given a tip, the attendant gave them the hair in a piece of paper.185