AROUND 10 OCTOBER 1813, less than six months after Wagner was born in Leipzig, Giuseppe Verdi was born near Busseto close to Parma. This was then part of Napoleon’s puppet Kingdom of Italy, so the boy was registered as Joseph rather than Giuseppe. When he died on 27 January 1901, Queen Victoria was lying in state in Osborne. Their demise was celebrated with comparable state funerals. Just as the Queen dominated 19th-century Britain, Verdi stands astride the music of 19th-century Italy.

Verdi knew exactly how to convey emotion and drama in beautiful melody. The arias which we love, such as ‘La Donna è Mobile’ from Rigoletto, have a naturalness and simplicity. His operas therefore provide a contrast to the complex, ‘orchestral’ operas of Wagner. They are essential items in the opera house and elsewhere: how many brides have walked down the aisle to the strains of the Grand March from Aïda! No matter that theat-rical productions of the March often include elephants and giraffes.

With a canny sense of timing and some genuine sympathy, Verdi espoused the cause of Italian nationalism. The combination of his music and his stories conveyed an emotional message to his compatriots, who yearned for delivery from despotic monarchs. This was an aspect which the check-list used by the strict but pedantic censors was not designed to identify. Thus, Verdi could emulate the work of the poet Alessandro Manzoni, whose tragedy Adelchi, about Charlemagne’s overthrow of the Lombard domination in Italy, contained many veiled allusions to the burden of Habsburg rule. In Verdi’s La Battaglia di Legnano, the knights swear to repel Italy’s tyrants beyond the Alps. No wonder that, on the eve of their revolution, the citizens of Rome were delirious about it. No wonder that the chorus in Nabucco, ‘Va, pensiero’, in which the captive Hebrews long for their homeland, launched Verdi’s career.

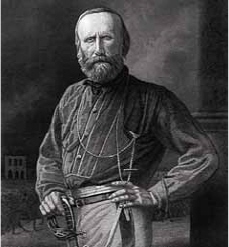

Verdi’s direct contribution to the revolutionary cause was, however, limited to setting rousing words to beautiful and memorable tunes. During the upheavals of 1848, he was actually based in Paris pursuing his career and his mistress, the former prima donna Giuseppina Strepponi. However, the story of the unification of Italy is such important background to Verdi’s life that, having considered his early years, we must return again to it and to the achievements of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the colourful freedom-fighter, who led the battle for it.

The 1850s saw the three important and very popular operas by Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata – which were less obviously political. Thereafter, the rate of composition decelerated and came to a halt with Aïda, which was produced in Cairo on Christmas Eve 1871, and the Requiem of 1874, written in honour of Manzoni. There was a long pause before Verdi emerged from retirement to write the two last operas, Otello, produced in February 1887, and finally Falstaff, which was premièred in 1893, just before he was 80.

Verdi kept away from, and was not asked to join, the titanic struggle that rent the musical world to the north: he is not to be found on either side of the fissure which divided Brahms and his adherents from the New Music of Berlioz, Liszt and Wagner. This irritated Verdi, who was annoyed that the new generation did not regard his work as modern art. But with Otello and Falstaff, one an opera seria, the other an opera buffa, both unarguably great works of art, Verdi brought the development of Italian opera to its ultimate conclusion. Italian operas composed afterwards, even those of Puccini, are at best but an imitation of what Verdi achieved.

VERDI’S EARLY LIFE

Verdi’s story was by no means the rags to riches one that legend (and particularly he) would have it be: his family, small-holders, were among the less than ten per cent of the population who could read and write.1 Carlo, his father, was an innkeeper who got into trouble for failing to pay his rent and for various irregularities such as permitting unlicensed gambling to take place on his premises; his mother was the daughter of another inn-keeper from a few miles away.

Giuseppe Verdi was born in a small two-storey house* in Le Roncole, a small village a few miles from Busseto. We can imagine that, outside Carlo’s inn, ‘there hung a grey dishcloth attached to a stick; on the cloth was inscribed the word Trattoria’. Perhaps ‘a tattered bedsheet, supported on two very slender wooden hoops and hanging down to within three feet of the ground, protected the door from the direct rays of the sun’. Perhaps the bed-room was very large and fine; perhaps it had ‘grey canvas instead of glass in its two windows’ and ‘four beds, each six feet wide and five feet high’.2

As he grew up, solemn young Peppino helped in the inn and played the organ in the little church which was about a hundred yards from where he was born. One day, the priest, whom he was assisting at Mass, angrily swore at him, saying ‘May God strike you down’. Shortly afterwards, the cleric and two choristers, but fortunately not Verdi, were struck by lightning. This episode did not endear Verdi to religion.3

Verdi was keen to progress, so the local organist persuaded Carlo to buy him an old spinet, hardly a normal item of furniture for such people. A friend repaired it for free. When the organist died, Verdi took over, and on high days and holidays he had to return to Le Roncole from Busseto, where he went to school, and lodged with a cobbler.

When he was twelve, Verdi had lessons in counterpoint and composition from a Busseto organist. He was sponsored by Antonio Barezzi, a prosperous, flute-playing grocer and distiller who started the local Philharmonic Society. Barezzi became a second father to him; on Barezzi’s death many years later, Verdi said: ‘I owe him absolutely everything.’4 The Philharmonic Society of around 70 amateur musicians no doubt played marches, overtures and variations, and the latest hit by Rossini. It also played compositions written by the young Verdi, who soon fell in love with Barezzi’s elder daughter Margherita, and wanted to be in a position to marry her.

When he was nearly nineteen, Verdi applied to enter the Milan Conserv-atoire, but he was turned down on several grounds: he was too old, there was no room, he had learnt an inappropriate piano method, and his counterpoint needed discipline. Also, he was a foreigner: his home state of Parma, although a puppet of Austria, was a separate country from Austrian Lombardy.*

Having been rejected, Verdi was advised to go to Milan and study privately. Apart from the Napoleonic interlude, the walled city of Milan had long been one of the most important and lucrative possessions of the Habsburgs. It had a correspondingly impressive musical tradition, employing Giovanni Battista Sammartini, and, for a time, Bach’s son Johann Christian, who later moved to London. The Ducal Theatre, which had been burnt down in 1776, had been replaced by La Scala on the site of the church of Santa Maria della Scala. With financial support from Barezzi, Verdi studied privately with Vincenzo Lavigna, a minor composer who had had some success at La Scala. He gave Verdi an excellent grounding in counterpoint and fugue.

Verdi, who seems to have led the high life, lodged with his former headmaster’s nephew and chased his daughter.6 There were complaints about his ‘boorish manners’. He was described as ‘ill-educated in his manners, arrogant and … something of a scoundrel’.7 Barezzi ticked him off. But Verdi was learning works by Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, and hearing performances by prima donnas such as Malibran and Pasta. He was progressing: he accompanied a rehearsal of Haydn’s Creation on the piano, but soon had taken over the baton; in the end, it was agreed that he should conduct the performance.

Although apparently Verdi could have been appointed to the well-remunerated post of organist in Monza Cathedral, he chose to return to Busseto as local director of music. Verdi’s behaviour in Milan, and his freethinking religious views, may have led the residents of Busseto to suspect him of being a liberal; indeed, had he worn his distinctive black beard at this time, they would have been sure that he was a member of that ‘most insolent set of people’. The novelist Stendhal, who knew Italy well, wrote in 1839 that ‘the deepest dungeons were reserved for the blackest Liberals’.8 We should not therefore be surprised that the residents of Busseto did not want Verdi as organist of their principal church. They put forward their own candidate, one Giovanni Ferrari, for that job. What may seem petty to us was important to them: the violence between Ferrari’s and Verdi’s supporters reached such a pitch that the dragoons were called in, and at one stage the duchess felt obliged to forbid music in the Busseto churches.

Eventually, Ferrari was appointed organist and Verdi took the municipal duties, which entailed giving lessons at the music school and conducting concerts of the Philharmonic Society. Verdi entered into a three-year contract with the municipality for 657 lire per annum, rising to 1,000 lire.* Although embittered, this gave him security and a position. He could marry Ghita Barezzi and settle down for three years to the life of a provincial music master in this insignificant town, which is set in flat countryside relieved only by the view of the Apennines in the far distance.

A daughter was born nine months after the wedding, and then a son. They were called Virginia and Icilio, both names with liberal overtones. Virginia lived only for seventeen months. It must have been a difficult time for the restless and ambitious Verdi, who had started work on an opera, Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio. He did not renew his three-year contract in 1839, but moved back to Milan. There he could try to get Oberto staged. He could also attend the salons, where aristocracy and artists could mingle well away from the government, whose officials were usually kept out.10

La Scala was run by the impresario Bartolomeo Merelli, who also ran the Kärntnertor theatre in Vienna. Oberto was premièred at La Scala in November 1839, after Verdi had made various adaptations as requested. It was sufficiently successful that the publisher Giovanni Ricordi** bought the rights for 2,000 lire. Merelli commissioned three further operas to be given at intervals of eight months.12

Although Verdi seemed to be starting to make his way, this was a difficult and tragic time. After deducting the 50 per cent payable to Merelli, the proceeds from Oberto were equivalent to Verdi’s previous annual salary; but money was short and Ghita had to pawn her jewellery in order to pay the rent. Then Ghita and Icilio died quite suddenly; Verdi himself suffered throat trouble.13 Disaster struck professionally as well: the first of the commissioned operas, Un Giorno di Regno, was taken off after the first performance. Verdi never forgave Milan for this, just as he nurtured his dislike of the citizens of Busseto, and kept in his desk a reminder of his rejection by the Conservatoire.

NABUCCO AND SUCCESS

According to one account, Merelli found Verdi a libretto which had been turned down by a leading composer based in Vienna, Otto Nicolai. Verdi was particularly attracted by its Hebrew chorus ‘Va, pensiero’, with its yearning for freedom. Nabucco was produced at La Scala in Spring 1842.

The lead role of Abigaille, the unpleasant eldest child of King Nabucco, was sung by Giuseppina Strepponi, a star prima donna of the 1830s. (Verdi had nearly succeeded her father as organist of Monza Cathedral.) Verdi was apprehensive about the première. Exhausted by overwork and the stress of giving birth to a succession of abandoned children,14 Strepponi’s voice had deteriorated to such an extent that it was unusual for her to perform well for three successive days. Fortunately, she was in good voice on the night, and the première was a success.

Indeed, it was a triumph. When it was revived in the following autumn, it ran for 57 performances, ‘a figure unmatched before or since’ in the annals of La Scala.15 Verdi visited Vienna and toured Italy. Old Carlo was able to witness his son’s success during the run at Parma in the spring of 1844. Nabucco was put on in all the major centres in Europe, in New York, and in such less likely places as Algiers, Constantinople, Havana and Buenos Aires.

The censors seem to have overlooked the political message in Nabucco, as they did for Verdi’s next opera, I Lombardi, which was premièred at La Scala in November 1843. This was about crusaders who express much the same emotions as the Hebrews in Nabucco. When the censors reviewed I Lombardi, they were primarily concerned with changing an aria beginning with ‘Ave Maria’ and having the baptism of an infidel removed. They seem to have had no premonition of the effect that Verdi’s melodies and ‘strong, slow-surging rhythms’ would have.16 Verdi asked Count de Bombelles if he could dedicate it to the Duchess of Parma; she received him and presented him with a diamond pin.

After Verdi’s initial success, he thought about writing operas based on King Lear and Byron’s The Corsair. Occasionally, he returned to the idea of an opera about King Lear, but he never created it: perhaps the story was too like Nabucco, the mad king with a nasty child. For Venice, he thought about The Two Foscari, also by Byron: but he was worried, at this stage, that the story might offend some of the Venetian nobility. Then Verdi was introduced to Francesco Maria Piave, the son of a glass manufacturer from Murano. Verdi was not motivated by Piave’s suggestion of an opera about Cromwell, and instead they worked together on Victor Hugo’s Ernani, the drama which had caused such a sensation in Paris on its first night in 1830. The opera was produced in Venice’s La Fenice in March 1844. ‘Ernani was more than a success; it became a fashion, keeping Verdi’s name before the public.’17 It represented the start of the partnership with Piave, who wrote the librettos for Rigoletto, La Traviata and La Forza del Destino.

Verdi was soon recognised as the leading opera composer in Italy. Bellini was dead, Rossini had retired, Donizetti was in an asylum; the only other contender was Saverio Mercadante, the director of the Naples Conservatoire. Verdi was accepted in Milan society: a salon which he frequented was that of Countess Clarina Maffei, whose husband, an improbable combination of government official and poet, was involved with the librettos of Macbeth and I Masnadieri. At this salon, Verdi met members of Young Italy, a conspiratorial and anti-clerical society of under-40s which the journalist Mazzini had founded.18 Its aim was a united republic of Italy. However, Verdi did not join it.

He planned to work himself hard, spending ‘years in the galleys’, and then retire, as Rossini had done.19 So he composed, he travelled, almost to exhaustion and certainly to depression. Between Ernani in March 1844 and Rigoletto in March 1851, he composed or arranged eleven operas: I Due Foscari, Giovanna d’Arco, Alzira, Attila, Macbeth, I Masnadieri, Jérusalem (the French version of I Lombardi), Il Corsaro, La Battaglia di Legnano, Luisa Miller, and Stiffelio.

Verdi’s appeal to patriotic emotions, as expressed in Nabucco and I Lombardi, was the secret of much of his success at this time. In 1846, around the time of the accession of Pope Pius IX, seen then as a great liberator, the Bolognese audience at Verdi’s Ernani chanted ‘A Pio Nono sia gloria ed onor’* to the music that accompanied the king’s granting of a general pardon.20 Verdi’s opera with the title Giovanna d’Arco obviously had patriotic overtones.

Verdi was demanding on his librettists and specified in meticulous detail what he wanted musically and in the staging. ‘Study closely the dramatic situation, and the words’, he said; ‘the music comes of itself.’21 From several preliminary sketches he would prepare a skeleton, with the vocal lines, the bass and a few instrumental cues. Then he wrote the singers’ parts. He left the orchestration until the piano rehearsals, at which he moulded the composition, even giving the specific singers alternatives from which to choose. For the Act 1 duet in Macbeth he had over 150 rehearsals, holding up the dress rehearsal for more, so much so that Macbeth seemed to be about to murder Verdi rather than King Duncan. His effort was rewarded: on the first night, there were over 30 curtain calls.22

At this time, Verdi’s operas were by no means always successful. And he was not always well-regarded, especially beyond the Alps. Nicolai, who composed The Merry Wives of Windsor (Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor) in 1849, wrote in his diary: ‘the Italian opera composer of today is Verdi … But his operas are truly dreadful and utterly degrading for Italy. He scores like a madman, is quite without technique and he must have the heart of a donkey and in my view is truly a pitiful contemptible composer.’23 There were complaints that he forced singers’ voices: Hans von Bülow called him Attila to the throat. Queen Victoria observed in her diary that his music was ‘very noisy and trivial’;24 but maybe she was annoyed that he had refused to be presented to her.

Unlike so many great artists, Verdi was a good businessman. If a theatre would not pay him his advance, he suspended rehearsals. He commanded big money. However, the English would not stump up the equivalent of the 90,000 lire, the country house and carriage which he required as compensation for becoming the musical director at Her Majesty’s Theatre.25 By the time of La Battaglia di Legnano and Luisa Miller, he had earned enough to retire, and he indicated in his letters to friends that he shortly would.

Verdi now applied his business acumen to his farming enterprise. He had bought himself a palazzo in Busseto in 1845. Three years later, he bought the country house and farm at Sant’Agata, which is a couple of miles the other side of Busseto from Le Roncole. His family had originally come from there, but his choice of location was surprising, given his aversion for the people in his home town.

At first, Verdi spent most of his time in Paris, and he established his parents at Sant’Agata. Carlo managed the property incompetently and there was a dispute, even to the extent that father and son had to correspond through lawyers. His relations with his father may well have been soured by his own irregular domestic arrangements with Strepponi (see colour plate 44), which very possibly began with the Parma performance of Nabucco in 1844.26

Peppina Strepponi had been trained at the Milan Conservatoire, and Verdi came across her when she was cast in the first performance of Oberto and then, of course, in Nabucco. She had a ‘lovely figure and, to Nature’s liberal endowments, she adds an excellent technique’.27 As was so frequently the case when singers needed money, she had strained her voice by singing too much too young. By the time she was 31, she was exhausted and had to retire. Verdi had provided her with a letter of introduction to the Escudier brothers, publishers in Paris, and she set up there, running a singing school for young gentlewomen. At this time, Verdi wrote her a love letter, sealed and never opened;28 thus, we shall see, it remains. He joined her in Paris, where they lived together. They were resident there during the Italian upheavals of 1848–9, which now demand our attention.

THE LIBERATION OF ITALY: 1848–9

Verdi was in sympathy with the momentum to remove the Habsburgs from Italy.* In 1847, a performance of Nabucco almost caused a riot in Milan, and the conductor Angelo Mariani was threatened with imprisonment for fomenting rebellion. Although Verdi took no active part in politics, he was perceived as ‘a prophet of the people, of the forces of nationalism that were carrying Italy in its tide’.29 In this, he was consistent with writers such as Alfieri** (who coined the word ‘Risorgimento’ to denote the resurgence of Italian national consciousness)30 and Manzoni; and with the recent moderate writers and journalists who advocated an end to Habsburg rule but did not necessarily go so far as calling for a united Italy.31 There appeared to be insuperable barriers to unification, not least the existence of the Papal States, which divided the peninsula geographically.

The upheavals of 1848–9 started in Sicily. Encouraged by the fall of Metternich in early March, Milan rose with the ‘Cinque Giornate’, the five days, and Venice proclaimed a Republic. Verdi returned to Italy very briefly during this time, and was in Rome for the première of La Battaglia di Legnano, which took place ten days before Rome was declared a Republic early in the following year; the opening chorus ‘Long live Italy, a sacred pact unites its children’ drove the audience into a frenzy, and the last act had to be repeated completely. But Verdi’s principal preoccupation at the time was the purchase of the farm at Sant’Agata.32

The revolutions eventually were crushed by the authorities. At the battles of Custozza and Novara,33 the Habsburg army put down the insurrection in northern Italy, including Milan, by defeating the Piedmontese. * The Habsburg armies then bombarded Venice, which, starved and suffering from cholera, capitulated. Largely through the intervention of the French, the Roman Republic was destroyed. Pope Pius IX returned to his throne. By this stage, Verdi, safely back in Paris, was wringing his hands about the wretched times in which they lived.34

But despite the setbacks, two important ‘players’ had survived: Mazzini and Garibaldi, the ‘brains’ and the ‘brawn’ respectively. There was also a king committed to the cause: the new King of Sardinia, Victor Emmanuel II, the ruler of Piedmont, which retained its ‘liberal’ constitution. The territory ruled by this dashing Re Galantuomo – whose main interests were women, hunting and eating peasant food cooked in garlic – became a haven for liberals. They formed the Italian National Society, pledged to support the cause for independence. The prime minister’s ‘Nous recom-mençerons’ expressed the determination of the Italians in the north to oust the Habsburgs and their allies in Rome and Naples. Victor Emmanuel would eventually become the first King of Italy.** However, his success was derived not so much from his own efforts as those of the irregular forces led by Garibaldi, and most particularly because of events abroad.36

THE LIBERATION OF ITALY: THE 1850S AND

THE BATTLEOF SOLFERINO

Although the revolutions of 1848–9 had failed, Italy was unstable and the violence continued. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, with its capital in Naples, was regarded as an outrage by liberal-thinking people elsewhere. One former minister, who was sentenced to 24 years in irons, in a dungeon, was visited by the English politician William Gladstone. In foetid darkness, occasionally being given a portion of stinking soup, the prisoners were allowed to emerge, as in Beethoven’s Fidelio, for half an hour on Thursdays to see their friends. In an exaggerated ‘polemical publication of vast impact’,37 Gladstone reported that there were 20,000 political prisoners in the Kingdom.* Not surprisingly, there was an assassination attempt in 1857 on the King of Naples. By this time, assassins had succeeded in killing Carlo III of Parma, and his successor could rule only with the aid of an Austrian garrison.

Camillo di Cavour, who became prime minister of Piedmont, realised that one consequence of the failed revolutions of 1848–9 was that the ejection of the Habsburgs and eventual unification would require external assistance.39 He stepped out onto the European stage and brought Piedmont into the Crimean War behind the French and British. He sought the help of Napoleon III, knowing that he had supported the Italian cause in the 1830s. The future of Italy was important to Napoleon because, paradoxically, in these decadent years of the Second Empire, Roman Catholics comprised an important and growing part of the emperor’s power base.**

To influence the Emperor’s attitude, Cavour supplied him, shortly after he married Eugénie, with the beautiful Countess Virginia di Castiglione, his own cousin and the mistress of his king. Cavour told her: ‘Succeed, cousin, by any means you like, but succeed.’41 In one respect, she did: Napoleon reputedly gave her a pearl necklace costing more than 400,000 francs, and an allowance of 50,000 francs a month at a time when a woman worker might expect to be paid one and a half to two francs a day.42 Whether or not Virginia had any political influence, in 1858 Cavour met the Emperor secretly at Plombières (in the Vosges). They agreed that the Habsburgs should be provoked into war and defeated. Afterwards, Piedmont would get northern Italy, while central and southern Italy would become French satellites all under the nominal presidency of the Pope. There was a price attached to the deal: Piedmont would transfer Nice and Savoy to France.

On New Year’s Day 1859, Napoleon III publicly provoked the Habsburg ambassador by saying that relations between their countries had deteriorated, while adding that he should tell his emperor that ‘my personal feelings for him have not changed’. War fever grew, with the slogan ‘Viva Verdi’ being widely used. ‘Verdi’ was actually an acronym for ‘Vittorio Emanuele Re d’Italia’, although the police could be persuaded that it meant something to do with the composer.43

The British, as might be expected, launched a diplomatic initiative to make peace. The Emperor of France, whom the Habsburg Emperor described as a ‘scoundrel’,44 then proposed a conference to discuss Italy. Vienna, who had nothing to gain from this, said that it would not participate unless Victor Emmanuel moved his troops away from their border. On 22 April, Vienna gave Piedmont an ultimatum to disarm; when they did not, Vienna declared war and Habsburg troops advanced on Turin.

Verdi’s house at Sant’Agata was only fifteen miles from the Habsburg positions at Piacenza. He professed that he would have liked to join up, ‘but what could I do who couldn’t even undertake a march of three miles? My head won’t stand five minutes of sun, and a breath of wind or a touch of damp sends me to bed for weeks on end.’45 He clearly did not regard himself as suitable military material. But he did get involved in fund-raising for the families of those killed.

The Habsburgs were not well prepared for the war. Their star general, Count Radetzky, had died and been succeeded by a far less resolute commander. Modern communication systems enabled France to get 200,000 soldiers to Piedmont in 25 days, some by sea, some by railway. On 4 June 1859 the Habsburgs were defeated by the French at the battle of Magenta. The Piedmontese stood and watched; the French lost 4,600 men; the Habsburg armies lost 10,200, but retreated in good order into their fortified area known as the Quadrilateral.46 Napoleon III and Victor Emmanuel entered Milan. The Parma royal family fled.

The Habsburg Emperor, who also had his wife’s antics on his mind – ‘Sort yourself out for love of me’, the desperate man wrote on 15 June; ‘get enough sleep and eat enough so you don’t get too thin’47 – took personal command. He hoped that the Prussians might come to his assistance, but they did not. On 24 June, Franz Joseph was again defeated, despite considerable Piedmontese inefficiency, at Solferino to the south of Lake Garda. This battle, with each side led by an emperor, saw the largest number of troops engaged since the Napoleonic battle of Leipzig over 45 years earlier. The French lost nearly 12,000 men, the Piedmontese around 5,500 and the Habsburg armies around 22,500.48 The bloodshed and sufferings were appalling: ladies went from French châteaux to serve as nurses at the headquarters at Solferino.*

Napoleon III was shocked by the carnage, fed up with the ineffective Piedmontese, concerned about the attitude of his Catholic supporters behind in France, and worried that the Prussians might attack him on the Rhine. He knew that it would be virtually impossible to get the Habsburg troops out of their fortresses in the Quadrilateral. So, much to Cavour’s annoyance, the two emperors met alone at Villafranca and negotiated an armistice.50 By this, the Habsburgs would lose Lombardy but would retain Venetia; and the Habsburg puppet rulers in the Central Duchies of Tuscany, Parma, Modena and Lucca, who had been thrown out, would be restored.

The Piedmontese paid for this by surrendering Savoy, their original family heirloom, and Nice, the birthplace of Garibaldi, to France. Verdi’s somewhat misplaced comment, considering the lamentable military performance by the Italians, was: ‘What an outcome after so many victories! How much blood shed for no purpose!’51

VERDI THE POLITICIAN

For Verdi, the immediately relevant part of the armistice was the imminent restoration of the Habsburg puppet regime in Parma. Verdi became an important figurehead in the process by which the people of Parma and the other Central Duchies rejected the restoration and instead voted for annexation by Victor Emmanuel. Plebiscites were held in which all males over 21 had the vote. But they were ‘a triumph of creative electioneering … Hitler and Stalin, in their heyday, never achieved results like this’.52 There was intimidation and, since most of the voters were illiterate, the ballot papers often had ‘Sí’ (Yes) already written on them. Fewer than 756 votes in all, 0.2 per cent of those voting, were cast against. Still, it was a colourful occasion, with bands playing, solemn processions and free wine flowing.

Verdi was elected the representative of Busseto, and in mid-September led the delegation that waited on King Victor Emmanuel and requested annexation. When this was implemented, Verdi was asked by Cavour and the British ambassador to become a member of the parliament which sat in Turin. As Cavour put it, Verdi’s presence ‘will contribute to the dignity of Parliament in and beyond Italy … it will convince our colourful colleagues from the south of Italy, who are very much more susceptible to the influence of your artistic genius than we denizens of the cold Po valley are.’53

While the proposed annexation was being considered, there was unrest. The mob took its revenge: the chief of police was recognised on the steps of Parma station and decapitated. Verdi was drawn into discussions about the deteriorating situation, but he tried to keep his direct involvement to a minimum. Shy and withdrawn as he was, he remained totally aloof from his constituency. He took his seat but rarely appeared, especially after Cavour died later in 1861. ‘I’m still a deputy against every wish and every desire, without having the slightest inclination nor aptitude nor talent’, he said.54 He resigned his seat four years later; his real interests, wisely if not heroically, were shooting, collecting autographs, gardening and developing his estates. He was not interested in politics.55

TOWARDS THE KINGDOM OF ITALY

Italy at this stage consisted of an enlarged Piedmont in the north, the Papal States in the middle, and the appalling Kingdom of Naples in the south. And the Habsburgs still ruled Venetia. Progress towards unification seemed slow, but the momentum continued.

Insurrection soon broke out in Sicily, which Garibaldi determined to support.

In early May 1860, he sailed from Quarto with 1,089 volunteers, ranging from a boy of twelve to a man of 60. After about eight weeks, in a brilliant and colourful campaign, he had expelled the Neapolitans from Sicily and was preparing to invade the mainland from the south. In September, he swept up through Calabria and entered Naples, accompanied by some English visitors who included the public orator of Cambridge University. The English were considerable supporters of Garibaldi: red blouses and round, kepi-shaped Garibaldi hats became fashionable in London at the time.56

Giuseppe Garibaldi

At a service in the cathedral, the blood of St Januarius, the patron saint of Naples, beheaded in 304 AD, liquefied in Garibaldi’s honour.57 For 62 days, until early November 1860, Garibaldi ruled all but a small area of the Kingdom as its dictator.

Verdi and Giuseppina were delighted: ‘Hurrah for Garibaldi!’, Verdi wrote. ‘God, he is a man before whom we truly should kneel.’58 But the Neapolitans did not like the boisterousness of his supporters, who swaggered around the streets and interrupted performances at the opera. The orchestra was required to play the ‘Garibaldi Hymn’ written by Verdi’s Neapolitan rival Mercadante,* a demand enforced at the point of the bayonet when the Garibaldini leapt into the pit.60

Cavour realised that the Piedmontese needed to seize back the initiative from Garibaldi, who, despite his effectiveness, was dangerously ‘red’ as far as they were concerned. Garibaldi’s determination to march on Rome would have brought international intervention, thereby putting at risk many of the achievements so far. The Piedmontese invaded the Papal States from the north, dispossessed Pius IX of the Marches and Umbria, and helped Garibaldi finally to defeat the Neapolitan army.

Plebiscites were held which approved Piedmont’s annexation of the various territories. Garibaldi met the king. ‘I salute you the first King of Italy’, said Garibaldi, and doffed his hat.61Meanwhile, Emperor Franz Joseph fulminated against ‘Garibaldi’s banditry, Victor Emmanuel’s thievery and the fraudulent practices of the Parisian scoundrel’.62

Garibaldi retired to Caprera, his island off the north coast of Sardinia, with his four donkeys which he named Pius IX, Napoleon III, Oudinot (the French general who defeated the Roman Republic) and the Immaculate Conception. This was much to the indignation of French Roman Catholics, but to the delight of English Protestants.63

FINALLY, VENETIA AND THEN ROME

Thus, by the end of 1860, the whole Italian peninsula had been absorbed into Piedmont, except for Austrian Venetia and a few remnants of the Papal States around Rome. On 14 March 1861, Victor Emmanuel declared the birth of the Kingdom of Italy, of which Florence became the capital. There had been no justification for conquering the Papal possessions, but the Piedmontese got away with it.

To the concern of northern liberals such as Verdi, the political scene remained disturbed. Garibaldi was still determined to take Rome, declaring ‘Rome or death’, a call to which Empress Eugénie responded: ‘Death if they like, but Rome never.’64 French troops were sent to defend Rome. In 1862, Garibaldi invaded Sicily and crossed to the mainland, but had no will to fight the Italian army and retreated into the mountains. When he was attacked, he refused to fire on Italians and was wounded and taken prisoner. When this news was received in Vienna, the value of shares on the stock exchange immediately rose by 10 per cent. But there was uproar elsewhere: there were demonstrations in support of Garibaldi all over Italy. The government in Turin fell. 100,000 people demonstrated in Hyde Park in London. In October, Garibaldi was released from prison and carried out on a special bed which Lady Palmerston, wife of the British prime minister, had sent him. Garibaldi visited England, where he was feted. The queen was not pleased, and noted in her diary: ‘Honest, disinterested & brave, Garribaldi certainly is, but a revolutionist leader.’65

It took two external events, the Austro-Prussian and the Franco-Prussian wars, to complete the unification of Italy. Neither was glorious for the Italians, but they resulted in Venetia being lost by the Habsburgs and then Rome being lost by the Pope.

At the time of the Austro-Prussian war in 1866, the Piedmont government agreed with the Prussians to open a second front against the Habsburgs, in return for being given Venetia. Franz Joseph was anyway prepared to give up Venetia in return for Italian and French neutrality. So, either way, Piedmont could obtain Venetia. But since Piedmont distrusted Vienna, war rather than neutrality was the preferred option. Italian troops gathered along the Po. In Sant’Agata, while focusing on writing Don Carlos, Verdi wrote: ‘I’m so near the field of battle that I wouldn’t be surprised to find a cannon ball rolling into my room one fine morning.’ 66 The Italians were duly defeated at the second battle of Custozza and in a naval battle at Lissa. But to the Habsburgs their victories were to no avail: after the Prussians defeated the Austrians at Königgratz in Bohemia, the Habsburgs were at last expelled from Italy. Meanwhile, La Fenice, the opera house in Venice, was kept closed.67

During this campaign, to keep him out of mischief, Garibaldi was invited to run a guerrilla campaign into the Alpine Tyrol.* His little army included Giulio Ricordi** and Arrigo Boito. Verdi had set a hymn by Boito for the London Exhibition four years earlier. Twenty years on, Boito, by then one of Verdi’s greatest friends, would write the librettos for Otello and Falstaff.*

After 1866, Rome was still outside the Kingdom of Italy. As we have seen from Liszt’s sojourn there, the 1860s saw some turbulent and, for some, surprising developments in the Roman Catholic Church. Verdi’s antipathy to them was exemplified in Don Carlos, performed two years after the Pope published the Syllabus of Errors. There is a central scene in that opera in which King Philip of Spain struggles to reconcile his duty to the Church with his personal feelings. Verdi required the Grand Inquisitor, representing the Church, to be ‘exceedingly old, and blind (for reasons which I won’t put down on paper)’.69

It took the Franco-Prussian War finally to dislodge the French garrison and leave the Pope exposed and unprotected. The French troops were needed at home, and the garrison withdrew. Pius IX was allowed to retain the Vatican with its dependencies, the church of Santa Maria Maggiore and Castel Gandolfo on the Alban Hill. Unification of Italy was at last complete. But Verdi, the unbeliever, was not entirely happy. ‘It’s a great event’, he wrote to Countess Maffei, ‘but it leaves me cold … I cannot reconcile Parliament and the College of Cardinals, freedom of the press and Inquisition, the civil code and the Syllabus … Pope and King of Italy – I can’t see them together even on the paper of this letter.’70

In November 1874, in recognition more of his wealth than anything else, Verdi was nominated a senator, ‘an honour which no more required his attendance in the Italian Parliament than does a peerage in the British House of Lords’.71 It allowed him free tickets for travel on the railways, although it is said that he always insisted on paying.72

The momentous events of the unification of Italy are important in the life of Verdi, if only because he played a relatively small direct part in them. He knew how to be politically correct: ‘You talk to me of music’, he said in 1848. ‘What are you thinking of? Do you think I want to concern myself now with notes and sounds? There should be only one kind of music pleasing to the ears of Italians of 1848 – the music of the guns.’73 But, apart from providing inspiration, he personally remained on the sidelines.

SANT’ AGATA AND THE PEOPLE OF Bz

In recording these political events, we have jumped ahead in time and must now return to the late 1840s and early 1850s. Around the time of the collapse of the revolutionary movement in 1849, Verdi and his mistress Giuseppina Strepponi returned to Italy from Paris. They moved their base to Sant’Agata, even though they returned to Paris for long periods. At Sant’Agata, Giuseppina occupied one bedroom on the ground floor leading out into the garden, while Verdi worked late into the night next door. He liked his estates. Giuseppina described how ‘his love for the country has become a mania, madness, rage, fury, everything exaggerated that you can say. He gets up almost at dawn to look at the wheat, the corn, the grapevines etc. He comes back dropping with fatigue.’74 His gun cupboard* can be seen in his bedroom.

A frequent shooting companion was Angelo Mariani, a leading conductor and a patriot in Milan in 1847–8. The two would spend hours at the piano or hunting in the woods by the banks of the Po. In later years, Mariani also helped the Verdis find the flat which they used in Genoa during the winter, and he occupied the flat next door.75

Verdi fell out with his father who, as we have seen, may have objected to the ménage with Giuseppina. Father and son separated ‘in residence and in business’,76 and Verdi provided his parents with a horse and an allowance. In this era, a person’s concern for their parents was regarded as a measure of their character, and Verdi’s treatment of his parents displeased the residents of Busseto nearby.

But, worse. The residents were ‘shocked’ by the Verdi ménage. They cut Giuseppina in the street and cold-shouldered her in church, much to Verdi’s fury. This confirmed him in his dislike of the local people, their clerical tendencies, hypocrisy and gossip. The upheavals over his appointment back in 1833 continued to rankle with him.

Verdi was rich enough to be able to ignore his neighbours. When his patron Barezzi expressed concern about the relationship between the celebrity and the town, he retorted: ‘Neither I nor she owes anyone an account of our actions.’77

The antipathy between Verdi and Busseto rumbled on. Verdi put his secretary and amanuensis Muzio* forward for the post of municipal musical director at Busseto, but he was turned down. Verdi refused to be named as the patron for the town’s Philharmonic Society. In the early 1860s, there was a row about the theatre, to be named Teatro Giuseppe Verdi. He felt that public money was being wasted at a time of national crisis. The local people felt that Verdi should pay towards its upkeep and activities. In the end, Verdi offered a large contribution, which also led to a misunderstanding when he claimed to offset it against some money owed him by the town. A box was reserved for his use but he never went inside the theatre.78

Giuseppina seems to have provided a stabilising influence on the tactless, humourless and unforgiving workaholic. Verdi and Giuseppina did not get married for eleven years; it is not clear why. It has been suggested that she thought herself unworthy of him, whatever that may mean. Alternatively, it has been suggested that, had they married, Verdi would have been obliged to accept responsibility for her surviving and abandoned children, so long as they were minors. Possibly to avoid embarrassment, when Verdi became politically prominent, at the time of the slogan ‘Viva Verdi’, they eventually did get married. The ceremony took place quietly at Collonges-sur-Salève in the diocese of Annecy.79 This was on 29 August 1859, around the time that the attention of the nation was focused on the battle of Solferino. They adopted the orphaned child of one of Verdi’s cousins, Maria Filomena, from whom Verdi’s heirs are descended.

RIGOLETTO, IL TROVATORE AND LA TRAVIATA

The 1850s saw three very important operas, Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata. With Rigoletto (La Maledizione,** as it was called at the time), Verdi had great difficulty with the censors. The Venetians totally rejected Piave’s libretto, its ‘repellent morality and obscene triviality’, and no doubt the picture of royal profligacy. Verdi reacted violently: ‘Putting on the stage a character who is grossly deformed and absurd but inwardly passionate and full of love is precisely what I feel to be so fine. I chose this subject precisely for those qualities, those original traits, and, if they are taken away, I can no longer write music for it.’80 The location was changed, the rape toned down, and King François of France became the Duke of Mantua whom we know. Premièred in March 1851, the opera was sensationally successful. Rossini said that Rigoletto was the first opera which made him aware of Verdi’s greatness. The sixteen operas which he wrote before Rigoletto are certainly less well known today.

Verdi then worked on Il Trovatore, but the poet who was writing the libretto died when it was unfinished. The management in Venice were keen to follow upon the success of Rigoletto, and became restive. So, with deadlines looming, Piave prepared a libretto based on Dumas’ La Dame aux Caméllias. Verdi worked on both operas at the same time.

Il Trovatore was first performed in Rome, very successfully. If the Venetian management had taken Verdi’s advice, it would have staged Il Trovatore. But the management insisted on pressing ahead with La Traviata, even though Verdi was not totally happy with it or the proposed cast. So the first night was a disaster: the sight of a healthily robust soprano dying of consumption seemed absurd. It was only after it was revived and Verdi made some changes that La Traviata became the success that we recognise today. Verdi was able to exclaim: ‘then it was a fiasco; now it is creating an uproar.’81

FRUSTRATIONS

After La Traviata, Verdi slowed down the intense pace of composition. The list of his compositions, dominated by opera, is considerably skewed towards his early years. Twenty-four operas were composed before he was 50; only four, Don Carlos, Aïda, Otello and Falstaff, were composed in the last 38 years. Meanwhile, the frustrations with productions and performances continued to occupy a considerable amount of his time.

He moved to Paris for a couple of years and adapted many of his operas for the Paris stage. He had an apartment in the Champs Elysées, but he disliked the social and operatic conventions of Paris. In 1855, he fell out with the star librettist Scribe, who wrote the libretto of Les Vêpres Siciliennes, because he was reluctant to make various changes which Verdi wanted. He tried to have its première stopped because of casting difficulties: the prima donna had eloped with a baron. Berlioz observed: ‘Verdi is having to wrestle with all the Opéra people. Yesterday he made a terrible scene at the dress rehearsal. I feel sorry for the poor man; I put myself in his position. Verdi is a worthy and honourable artist.’82

Simon Boccanegra, produced in Venice in March 1857, was not particularly successful. Verdi then considered writing a ‘King Lear’, but could not find the right singer to perform the part of Cordelia. He then had great difficulty with the Neapolitan censors over Scribe’s libretto about the assassination of Gustavus III of Sweden, which he used for Un Ballo in Maschera. He stormed out of Naples, and put on an altered version in Rome. But by then, Gustavus, who had already been changed to a fictional duke in Pomerania, had become Riccardo in colonial Boston.

As if these frustrations were not enough, Verdi also had difficulties with his publishers and with copyright. His operas were appearing in pirated forms. He complained to Ricordi about the conditions under which his foreign rights were being sold, and the practice of making available the plates rather than the original score, thus depriving him of his percentage. It did not help that both Ricordi and the French publishers suffered from what at best may be described as accounting and financial weaknesses; at worst, the publishers were just fraudulent.

Verdi was incurring considerable expenses on developing the property at Sant’Agata, even though it remained just a large country house built around a courtyard; there is nothing flashy or particularly grand about it. He was offered an attractive fee by a Russian for La Forza del Destino. Verdi and Giuseppina went to St Petersburg, but the production of La Forza was called off because some of the cast became ill. They returned to St Petersburg for the first performance in the following year, after a visit to London for the International Exhibition of 1862.

The production of Don Carlos commissioned for the Paris Exhibition of 1867 was not a success. Bizet found it full of good intentions and nothing else. The rehearsals had been disrupted by rows. The bass engaged for the role of Emperor Charles V complained that his part was not that of a principal; there was a fight between the prima donnas. Verdi preferred to miss a day’s rehearsal rather than ‘watch the grimaces of one soprano’ when the other was singing.83

January 1869 was a significant month because Verdi made his peace and returned to La Scala for the first time for twenty years. Performing in Don Carlos was a young soprano from Prague, Teresa Stolz. Verdi agreed to conduct a production of La Forza del Destino at La Scala in the following month.

AÏDA

In November 1869, when the Suez Canal was opened, the Khedive of Egypt planned also to open a new opera house in Cairo, as part of the cel-e brations. The opera season began with Rigoletto, and Verdi was asked to write a new work, Aïda, for the subsequent season. The idea of Verdi writing it was promoted by a French Egyptologist in the vice-regal service. Verdi was very reluctant.

Then, in July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War intervened. Despite the fact that a French garrison was propping up the Pope in Rome, Verdi was pro-French: ‘France gave freedom and civilisation to the modern world. And if she falls, don’t let us delude ourselves, all our liberties and civilisation will fall with her.’ He added: ‘Ah the North! It is a country, a people that terrify me.’84 He set aside 2,000 francs for the wounded from his Aïda commissioning fee. When Paris was under siege, so were the Aïda costumes. Thus Aïda’s première was postponed until the end of 1871.

In 1870, following the death of Mercadante, Verdi was offered the directorship of the Naples Conservatoire, but he turned it down. He did not want to move his home, and he wanted his independence to compose. He also said that to give effect to his ideas about musical education would require constant surveillance on his part: he expected students to be given a basic grounding, constant exercise in fugue and counterpoint, and a broad study of literature. He said: ‘Let us return to the past; it will be a step forward.’85 But he did agree to serve on a committee for the reform of music education which sat in the capital, Florence, in 1871.

THE REQUIEM

In 1873 the death took place, aged 88, of Alessandro Manzoni, a fervent Roman Catholic and virtually the sole exponent of the Romantic school in Italian literature. His works belong to the second and third decades of the century, when he wrote the tragedy Il Conte di Carmagnola and the historical novel I Promessi Sposi, which was described by Sir Walter Scott as the finest novel ever written, and by Verdi as ‘one of the greatest books ever to come from the human brain’.86 By the 1870s, he was regarded as the patriarch of Italian letters, and he was ‘one of the few human beings whom Verdi revered’.87 He was buried with great pomp at a state funeral in Milan.

Verdi’s Requiem Mass in honour of Manzoni was performed in May 1874 in Milan. Hans von Bülow launched an attack on Verdi’s ‘latest opera, though in ecclesiastical robes’, whereupon Brahms riposted: ‘Bülow has made an almighty fool of himself. Only a genius could have written such a work.’88 Wagner was far less enthusiastic: he said that the Requiem is ‘a work of which it is better not to speak’.89

A LONG PAUSE

After the Requiem, Verdi stopped composition for a long time. Although he wintered in his apartment in Genoa and frequently visited Milan, his main base was in Sant’Agata, where he enjoyed developing the formal gardens and running his 1,500-acre farm.

He created an ornamental lake with bridge and statuary, and a tree-lined drive from the house through the fields to the Ospedale which he had founded. He imported trees from as far away as Japan and South America. Both Verdi and Giuseppina were very fond of dogs; in the garden one can see a monument over the tomb of their dog, inscribed with the legend: ‘D’un vero amico’, ‘To the memory of a real friend’.

However, there are less unanimous stories about his care for his 200 workers. Some tell tales of Verdi being a harsh landlord whose land agent gave his tenants flour and meal which made even the pigs vomit. Others paint a different picture. Apparently, when times were hard, he raised wages and invested the farming profits in charitable projects such as the Ospedale and in a musician’s rest home in Milan, the Casa di Riposa. Although the more affluent classes benefited from unification, the lower classes did not: Verdi and Giuseppina made substantial gifts to relieve their abject poverty and hunger, which was aggravated by a tax on flour.

Whatever, to many people Verdi seemed unforgiving and dislikeable; descriptions like ‘testy’, ‘sly’ and ‘proud’ abound. Many years later, one commentator remembered Verdi as ‘very taciturn for an Italian’.90 Giuseppina, on the other hand, was apparently an endearing person.

TERESA STOLZ

Given the self-centred nature of Verdi’s character, his marriage was bound to be a rocky one, and it became increasingly strained as the years went by. He gave Giuseppina a very hard time; he was sometimes ‘so abrasive, so difficult’. ‘This evening there was an uproar about an open window … He flew into a rage saying that he would sack all the servants.’ He complained that she stood up for them ‘even when he makes perfectly justified complaints’. His attitude was perhaps summed up in his own statement: ‘Horses are like women; they have to please the man who owns them.’*

By the early 1870s, Giuseppina was in her matronly middle-50s. In September 1871, Teresa Stolz, who had sung many of Verdi’s heroines, and was nearly twenty years younger, paid her first visit to Sant’Agata to study Aïda under Verdi’s guidance; he had probably seen her first on the occasion of his return to La Scala. Teresa was ‘the Verdian dramatic soprano, par excellence, powerful, passionate in utterance, but dignified and disciplined in manner’.92 She had an instinctive feeling for the interpretation of Verdi’s music and an impeccable vocal technique.93

At the time, Stolz was engaged to the 50-year-old Angelo Mariani, once Verdi’s great friend and hunting companion. Although Mariani was totally devoted to Verdi, their friendship suffered when Verdi hatched a plan to mark the first anniversary of Rossini’s death: Verdi wanted a Requiem, to which all the leading composers would contribute. It would be given once only in San Petronio in Bologna, and then would be sealed up and deposited at the Liceo Musicale. Verdi’s controversial idea was not enthusiastically received. This annoyed him. When Mariani offered to provide the Pesaro chorus** to sing at it, Verdi wrote him a stinging letter: ‘Do you mean to say that we have to beg you to be allowed the chorus that you have at Pesaro?’, he asked.94

Teresa broke off her engagement to Mariani,† and Verdi took up with her. On Saturdays, Verdi would have an assignation with her in a hotel in Cremona. The press got hold of this, and published a series of lurid and defamatory articles during 1875. On one occasion, it was said that Verdi thought he had lost his wallet containing 50,000 lire. Obviously, his first reaction was to blame the servants, but then the wallet was found on Teresa’s sofa, having slipped out during some activity thereon. Another paper deplored the fact that, at a time of great economic hardship, Verdi should have such a large amount of money in his wallet.

Whatever the truth of the stories, the relationship caused Giuseppina bitter anguish, which was compounded by his ‘psychological and verbal violence’.95 She was reduced to pleading with him not to be abandoned. Somehow, however, Giuseppina, Teresa and Verdi managed to develop a successful ménage à trois.

THE LAST YEARS, O TELLO AND FALSTAFF

Verdi emerged occasionally. In 1879, following devastating spring floods, there was a charity performance of the Requiem. The following evening, the Verdis had dinner with the Ricordis. Giulio Ricordi steered the conversation round to the subject of Shakespeare, a dramatist who had always enthralled Verdi. Ricordi had identified Arrigo Boito as a librettist who could get Verdi to start composing again.*96

Verdi was gradually persuaded to compose an opera based on Othello. But first he revised Simon Boccanegra and abridged Don Carlos. He set to work on Otello in 1884–5. But when he heard a rumour that Boito wished that he himself were composing the opera, Verdi stopped writing and offered to return the libretto. Boito had to calm him down and persuade him that he alone could compose it. It was a slow process: Otello was eventually performed at La Scala in February 1887. Two years later, Boito sent Verdi a sketch for Falstaff, which was first performed in February 1893, Verdi’s 80th year.

Otello and Falstaff, the one tragic and the other comic, were Verdi’s crowning achievement. They were both received deliriously at La Scala. After Otello, according to Boito, the pandemonium was ‘insane: the crowd tried to shoulder Verdi’s carriage and carry it from La Scala to the Grand Hotel up the street’.97 The ovations for Falstaff lasted almost half an hour. For Verdi they were tinged with the sadness of knowing that they marked the end of his artistic career.98

Were it not for these last two operas, we might place Verdi on the same level as Donizetti and Bellini. Writing about Otello, one expert says that ‘the vocal lines display at its highest pitch of development Verdi’s genius for revealing character by the curve of a phrase. Subtle passing harmonies add their inflection to individual words while, on a larger scale, harmonic structures define and help to organise the musical structure. The orchestration is adventurous but unobtrusively so.’ Falstaff is full of ‘melodic abundance’.99

After Otello and Falstaff, Boito tried to tempt Verdi with Antony and Cleopatra, and he thought again about an opera based on King Lear. But Verdi was too old and tired; he had already had a stroke in 1883. On one occasion, Giuseppina, herself crippled with arthritis, found him lying in bed, seemingly paralysed and unable to speak. He scribbled on a piece of paper: ‘Coffee.’ This revived him.100

Giuseppina was operated on for an abdominal cyst in the 1880s. As she aged, she suffered from nausea which kept her from eating. She died in November 1897 at Sant’Agata, after an attack of bronchitis. She had requested that with her should be buried the love letter which Verdi sent her before she set up in Paris; but it could not be found. Eventually it was, but has remained sealed. The following year, Verdi published Quattro Pezzi Sacri, which were compiled at the time she was failing. To Laudi alla Vergine, written some years before, he added three other sacred works: Ave Maria, Stabat Mater and Te Deum. He himself was not religious; but Giuseppina’s bedroom has a crucifix above the bed, and a little shrine.

Verdi now lived most of the time in his suite in the Grand Hotel et de Milan, just down the Via Manzoni from La Scala. His good looks in old age drew compliments. Stolz was his companion. There is little doubt that there was a ‘passionate bond’ between them, even when he was 87 and she 66.101 Around them, the Italian political scene was chaotic. There were riots in Milan in 1897–8, and the king was assassinated in July 1900. The queen wrote a prayer for her dead husband; Verdi had tactfully to avoid her request to set it to music.

In January 1901, Verdi had another stroke. He collapsed when trying to button his vest. He had been living well: his menu for the day before included julienne en croûte, followed by truite grillée, boeuf à la jardinière, game and turkey, and asparagus; the meal concluded with raspberry ice cream and desserts. He lingered for a few more days.* Traffic was diverted, ram-drivers were told not to sound their bells outside; all was quiet. He died on 27 January.

Three days after his death, he was taken to join Giuseppina in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale; it was estimated that 200,000 people filled the streets. A month later, they were both removed to the Casa di Riposo. More than 300,000 mourners accompanied the cortège. The crowd broke softly into ‘Va, pensiero’, the moving chorus from Nabucco. It had launched his career, and also signified the Italian liberation movement with which he has been so much associated.

* There is some question about the actual location; the original birthplace may have been burnt by soldiers fighting in the Napoleonic wars.

* Parma was ruled by a duchess, Napoleon’s Empress Marie-Louise, who had obtained it by virtue of the Congress of Vienna. She lived there with her lover, the one-eyed Austrian General Count Neipperg, whom she married in 1821 after Napoleon’s death. When the first count died, she took up with another, René de Bombelles. The Lord Chamberlain responsible for the Vienna Opera when Mahler was in charge was a grandson of Marie-Louise.5

* Around this time, a travelling actor was regarded as well remunerated with 32 lire a month; members of the lesser nobility had an income of 3–4,000 lire per annum.9

** Ricordi started a copying business, and after study with Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig, set up his publishing business in Milan. During the first half of the 19th century, he absorbed Artaria’s business, and entered into exclusive publishing contracts with many of the opera houses in Italy. By 1837, he was able to advertise more than 10,000 publications, and by his death in 1853 had issued 25,000.11

* ‘Honour and glory to Pope Pius IX.’ Giovanna d’Arco was about Ste Jeanne d’Arc, who fought against English rule in France; St Joan had not been canonised in Verdi’s time.

* Events leading up to and during the 1848 revolution are described on page 288 et seq.

**Schumann read works of Alfieri before visiting Italy, aged nineteen. Verdi’s two children were named after characters in Alfieri’s dramas.

* The King of Sardinia, whose main sphere of operations was Piedmont, ruled from his capital in Turin. He had found himself in an improbable role as a champion of independence. After his defeats, he abdicated in favour of his son Victor Emmanuel II.

**His tomb, bearing the inscription Padre della Patria, is in the Pantheon in Rome. Cavour, who became prime minister in 1853, wanted the king to marry a Russian princess, so he insinuated that the king’s mistress Rosina had been unfaithful to him. Rosina countered by saying that the attentions paid to her were ‘so constant and insatiable that they left her with no appetite or stamina for other men’.35

* Gladstone’s findings were published in ‘A Letter to the Earl of Aberdeen’. The correct number was more like 2,000. His intervention earns his portrait a place in the Museo del Risorgimento in Milan.38

** The extent of the religious revival can be seen by the number of priests and nuns. In 1875, there was one priest to 639 people in the French countryside, whereas in 1821 there had been one in 814, an increase of over twenty per cent. The number of nuns had increased more than ten times since earlier in the century.40

* The horrors were related in a book by a young Swiss stretcher bearer, Henri Dunant, and this led to the formation of the International Red Cross at Geneva five years later.49

* A couple of years before, Mercadante had written a hymn for the accession of King Francis II.59

* Garibaldi was then told to withdraw from the Tyrol. He became increasingly outspoken, and a liability for the Italian government. He was imprisoned and returned to Caprera, where the Italians placed a naval patrol to blockade him. He escaped through a fog and, in yet another amazing flight, got to Florence. The French intervened again in support of the Papacy, and Garibaldi was defeated and arrested and confined to Caprera. Thereafter, he retired to write novels and re-marry. He died, in his bed, in 1882.

** Giulio Ricordi was the grandson of the founder of the Ricordi business.

*Meanwhile, their friendship was interrupted by Boito’s ode which compared ‘the defiled altars of Italian music to the splattered walls of a brothel’. Boito, the son of a destitute Polish countess, had just completed his studies at the Milan Conservatoire. He frequented the salon of Clarina Maffei and became prominent in the scapigliatura, a radical artistic movement reflecting the disillusionment that followed the initial enthusiasm for Italian unification. Despite its aims, its members were better known for their disorderly behaviour, holding forth in cafés, drinking absinthe and duelling. Boito’s attempts at opera composition ended when his Mefistofele lasted until well past midnight at La Scala.68

* The cupboard also contains some duelling pistols and an ordinary pistol.

* Verdi had employed Emanuele Muzio, one of his pupils who, like him, had failed to get into the Conservatoire; he was also from Busseto.

** The curse; the story was based on Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse.

* Verdi’s misogyny was not unique. In 1910, an article was published by Max Funke entitled ‘Are Women Human Beings?’ (‘Sind Weiber Menschen?’). It concluded that women are a missing link between Homo sapiens and less advanced species. In this context, Verdi’s comment may seem less extreme.91

** Pesaro was Rossini’s birthplace.

†Mariani died in lonely circumstances a couple of years later, after Verdi had tried to have him evicted from his apartment in Genoa.

* One may be mildly surprised when one hears that, in 1893, Cambridge awarded Boito an honorary doctorate as a substitute for Verdi. At the time when Boito was working on Otello, a young composer was introduced to him with the name of Giacomo Puccini. Boito ‘represented the foremost arbiter of Milan’s intellectual and artistic taste. Poet, writer, critic and composer in one person and the leader of Italy’s avant-garde, his influence was immense.’96

* A room at Sant’Agata has been furnished to look like the room in which he died. In it can be seen a plaster cast of his right hand, in which the third and fourth fingers are unusually the same length.