DESPITE HIS SECULAR SUCCESS, WILLIAM SHEFFIELD, A STATE SUPERIOR court judge in Orange County, California, was unsettled. “The question whether there was a God gnawed at me, and I needed to resolve it.” A nominal Episcopalian back then in 1984, Sheffield decided to enter the Yale Divinity School and explore things. In New Haven his wife, a “Jack Mormon” who hadn’t been to church in years, began attending LDS services with the kids, so he tagged along, unenthusiastically. When he heard the bishop deliver the standard testimony about Joseph’s First Vision and the golden tablets, “I said, personally, I’m not related to Disney or Spielberg.” But the bishop coaxed Sheffield into reading the Book of Mormon, and when a Yale Bible professor told him the Book contained some sophisticated theology, he began taking it more seriously. Eventually he decided that “it must be a great lie, or a great truth. It’s one or the other,” and further study at Brigham Young University convinced him that an ill-educated farm boy like Joseph Smith couldn’t simply have made it up. He received LDS baptism in 1985 and resumed his legal career in California.

Jana Riess, an active Presbyterian attending Wellesley College, befriended Mormon classmates and “wondered how such intelligent women could be involved in such a wacky religious group.” The summer before entering Princeton Theological Seminary to train for the ministry, she visited Joseph Smith’s Vermont birthplace and accepted a missionary guide’s challenge to read Smith’s scriptures for herself. “I really fell in love with the Book of Mormon,” she said, and began migrating toward some aspects of LDS doctrine. “Mormons don’t really believe Jesus was God, and I don’t either.” She was baptized LDS in 1993, months before graduating from seminary. Her husband, who remained Methodist, “took it wonderfully.” Forsaking a clergy career, she became a doctoral student in American history at Columbia University and the religion book review editor of Publishers Weekly.

But adjustments remained to be made that may say something about twenty-first-century Mormonism, since the bulk of converts, like Riess, come from conventional Christian backgrounds and more are well educated. She said Smith’s doctrine that God the Father has a physical body was “a challenge for me, because I was trained as a theologian.” No Mormon prophets or apostles have ever had the equivalent of her own Princeton training. As for governance from top to bottom by an all-male priesthood, this self-avowed feminist admitted, “I can’t say I have come to terms with it.” Further, “it’s hard to relate to the cultural baggage, certainly of gender roles, but also the deification of the General Authorities.” More off-putting yet was the church’s campaign against free-spirited intellectuals such as the September Six. “I find this McCarthyite ‘guilt by association’ stuff very frightening. If they win the victory in those terms, they will lose the war.” But at the grassroots level “the church creates a community like none I’ve seen in other religious groups” or anywhere else in our unstable culture. “I’m much happier as a Mormon than I was as a Protestant.”

Sociologist Thomas O’Dea might not have imagined the likes of Sheffield or Riess converting to the church when he wrote his classic 1957 study The Mormons. The faith was then disseminated largely on the basis of clan and just beginning its nationwide diaspora. To some, the future seemed problematic. O’Dea reported that critics (unnamed) thought Mormonism would enter “a long twilight” leading toward “obsolescence,” if not “extinction.” Once the western wilderness and Gentile prejudice had been conquered, so the thinking went, the church’s tightly organized “posture of combat” was ill fitted to cope with American normalcy. O’Dea didn’t buy that prophecy of doom, but he did forecast future problems. The budding movement for women’s equality would cause no disruptions within the fold, he figured. (The black priesthood issue was so unimportant that he did not even mention it.) But O’Dea warned that the church lacked the contemplative and philosophical resources it needed for long-term strength now that the older emergencies were behind it. He saw related difficulties: Mormonism’s awkward “encounter with modern secular thought” and the “unhappy intellectual group” that was emerging within the church.

Correct description, wrong prescription. The church has prospered handsomely while doing little to accommodate the philosophical cast of mind, secular thinking, or unhappy intellectuals. Theological confusions and historical anomalies, the sorts of things that bother scholars, have mattered little. Ours is a relational era, not a conceptual one. Members are more likely to be attracted by networking and community than by truth claims. The adherents appear to be contented, or docile in their discontent, except for some thousands of liberal dissenters.

Reactions to purges barely register on the Richter scale. And the LDS church is one of the few large American denominations without a significant feminist wing. The Saints do not seek a voice even on mundane matters. Sure, one of the nation’s best-known Mormons could say, “I think people who pay the tithe should be allowed to know how the money is spent.” But he was Jack Anderson, an investigative reporter. Some might wonder how an authoritarian and secretive church could maintain appeal within an open democratic culture like that of the United States. However, the Mormon administrative style is inspired by corporate America with its top-down authority and information controls, not democratic America. The future of Mormonism will be shaped by former businessmen and Church Educational System teachers, not theologians or social analysts.

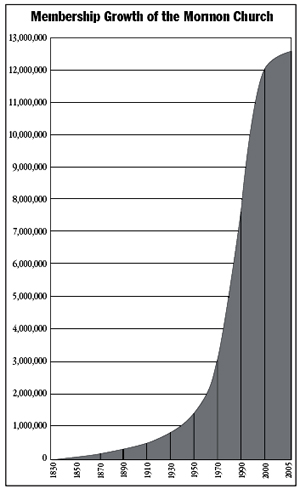

Twenty-seven years after O’Dea, sociologist Rodney Stark presented a different forecast. He projected that by a.d. 2080 the Saints would increase to some 64 million worldwide by a conservative reckoning, or about 267 million if they kept up their postwar pace. Stark updated the “Mormon miracle” in 1998 and the 2005 anthology The Rise of Mormonism, and answered critics of his straight-line projections by noting that LDS expansion was exceeding his high-end estimate.

But the future could be more complicated than that.

Stark predicted LDS success even as cultures modernize and secularize. He said “sects” within a religion may prosper in less secularized situations. But when conventional faiths soften under strong secular cultural pressures, this aids expansion of “new religions—of cult movements that represent an unconventional religious tradition,” with Mormonism providing a prime example. Of course, loyal Mormons reject categorization as a separate “new” religion and certainly as a “cult,” portraying themselves instead as the unique restoration of true Christianity.

During Gordon Hinckley’s presidency, his church surpassed the memberships of the Church of God in Christ, National Baptist Convention U.S.A. Inc., and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, to become the fourth largest U.S. denomination (behind the Roman Catholic Church, Southern Baptist Convention, and United Methodist Church). The 2007 LDS Church Almanac listed 12.56 million Saints worldwide, of whom 5.69 million (45 percent) lived in the United States. LDS totals count unbaptized children (typically those under age eight). And as with many other denominations, the data on baptized members do not consider how many have drifted into inactivity or unbelief while remaining on the rolls. Dropouts are the reason Jehovah’s Witnesses do not grow faster, despite door-to-door evangelistic efforts far surpassing even those of the Mormons.

Asked why he thinks converts flock in, Hinckley said “they find sociability. They find friends. We’re a very friendly church. We’re a happy, go-ahead people, and others like it.” In addition, “they see in this church an anchor in a world of shifting values. The family is falling apart in America and across the world. We’re putting strong emphasis on the family. It’s appealing to people. They like it. They welcome it. They need help, and we offer that help. Furthermore, it gives purpose to life. We give a point of view. We answer the old questions of where did I come from, why am I here, where am I going? These great religious questions have been asked by men throughout the ages. We give them an assurance of who they are, sons and daughters of God. People find comfort, they find peace, they find strength in that.”

Secular scoffing has done nothing to deter Mormon advance or to discourage Hinckley in his activist presidency. “The time has come for us to stand a little taller, to lift our eyes and stretch our minds to a greater comprehension and understanding of this, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” he told his first General Conference as Smith’s fourteenth successor. “It is a time to move forward without hesitation.”

He significantly increased the worldwide construction of temples and meetinghouses, a campaign reminiscent of a building binge that nearly bankrupted the church a generation earlier. But Hinckley’s church did not seem short of cash, and his team devised economical micro-temples to serve the increasingly far-flung membership. A long-term question looms, however. To what extent are American tithe-payers subsidizing the church in less affluent countries, and how long can they do so if pell-mell growth persists? Given the LDS penchant for secrecy, only a handful of men among the millions know the answer. But chances are that the new temples and meetinghouses are prudently budgeted out of current income, since the church dislikes indebtedness. If a crunch occurs, the church has substantial cash reserves and investment resources on hand to supplement current income. In addition, the new temples can be seen as investments in that the announcement of a new temple appears to increase regional members’ desire to fulfill the tithing regulation and obtain temple access. Meetinghouses may similarly foster offerings. Officialdom is thought to be rather conservative in the spending of assets, and, due to centralized control and flexibility of the system, readily able to balance expenses and available funding.

Though the statistical reports that flow across Hinckley’s desk may enhance a sense of well-being, LDS analysts have taken a bit of the shine off the glowing numbers. The church’s own research unit, which may know about retention problems, releases few findings, and Marcus Martins, BYU-Hawaii’s religious education chairman, has complained that scholarship is often inadequate because since the mid-1990s the church “no longer grants access to independent researchers, which makes it almost impossible to conduct large-scale surveys.” Still, some shards of information are available. Regarding Brazil, which ranks third among nations in Mormon population, one observer estimated in 1988 that only 15 to 20 percent of those on the membership rolls were very active, another 30 to 40 percent were nominally active, and some 40 to 55 percent had little or no contact with the church. A sour ex-Mormon who had done a mission in Rio de Janeiro claimed that most of the converts were children and uneducated adults who yielded to authoritative argumentation and evangelistic pressure for baptism but then quickly abandoned the faith.

In South Africa the leader of the black branch near Cape Town told journalist Peggy Fletcher Stack that the members’ weekly attendance rate was around 25 percent and that missionaries probably rush prospects into baptism without adequate preparation. In the United States a report found that the attrition rate among African American converts was 60 to 90 percent in Columbia, South Carolina, and Greensboro, North Carolina. If those two towns are at all typical, there is a major, if unacknowledged, problem. It is unclear whether blacks defect when they learn about the Mormon prophets’ previous racial theology.

BYU sociologist Tim B. Heaton reported in 1992 that Mormons’ weekly attendance rate in Asia and Latin America was only about 25 percent. (Healthier rates of 40 to 50 percent were reported for the United States, Canada, Africa, and the South Pacific.) In the United States a survey cited by Heaton showed that 33 percent of Mormons were “disengaged,” with 19 percent believing but no longer attending and 14 percent neither believing nor attending. (Heaton estimated that excommunication and formal resignation affected less than 1 percent of the membership, though those figures are not made public.)

Lawrence A. Young, a BYU professor who wrote a 1994 study of Melchizedek priesthood figures as a clue to retention rates, theorized that “part of the failure in some countries is due to Mormonism’s inability to find indigenous expressions of its community that allow new members to accommodate to both the church and the host society.” With a 70 percent rate of ordination to the Melchizedek priesthood in Utah, the faith had the closest cultural “fit,” and did pretty well elsewhere in North America, but seemed quite alien in a nation like Mexico, where the retention rate plummeted to 19 percent. In Utah, Mormonism is not just a shared creed but an ethnic identity and family heritage, with a good dose of frontier nostalgia mixed in. The same is true, less intensely, elsewhere in the United States. But overseas, Mormonism is a belief system seeking to create a community. Because statistics on Melchizedek ordinations are less triumphal than baptismal figures, perhaps, the church almanac no longer issues those figures.

Compared with other world missionary faiths, the LDS Church bears heavy nationalistic baggage. It proclaims that God commissioned a prophet in the United States uniquely to restore the scriptures and priesthood, that Jesus Christ will return to Missouri and establish the future millennia kingdom when the earth is 7,000 years old, and that the American constitutional system is uniquely the product of divine inspiration. When the Mormon folk selected their own special holy day, it was not the anniversary of their prophet’s birth, the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, the establishment of the priesthood or of the church, but Pioneer Day, celebrating Brigham Young’s 1847 arrival at the Salt Lake Basin. Moreover, Mormons believe that God has granted total control of his one and only church to fifteen men in Salt Lake City, almost all of whom have been Americans.

Martin E. Marty, the University of Chicago historian, has said “this is the only religion with scripture set partly in America. It’s an American book, ready to go. They know their slot, and it’s a huge market: the Norman Rockwell, Lawrence Welk, flag, Boy Scout, anti-gay, anti-ERA world. They are so American—after being so hated.” Hinckley played down Americanness. “Our message is universal. It isn’t an American message.” He also insisted that “our leadership is universal,” referring to the ward and stake leaders overseas rather than to the Yankees who retain nearly all the real power at the top. The few foreigners chosen for ascent are quite likely to be those who are the most Americanized and the most obedient to the American hierarchy.

In the early twenty-first century, there were indications that the LDS engine could be slowing down a bit. The 2007 edition of the standard Yearbook of American & Canadian Churches challenged the oft-heard “fastest growing church” scenario, charting a 1.63 percent LDS membership increase in the United States since the 2006 Yearbook, lower than the growth rates for the Roman Catholic Church and Assemblies of God. The church reported that 306,171 converts were baptized worldwide in 1999, or 2.8 percent of total membership, but only 272,845 in 2006, or 2.1 percent of membership. This despite the opening of more local branches and national fields. Comparing 2002 with 2005, the total of missionaries in service dropped from a high of 61,638 to 52,060, and new missionaries called in the year declined from 36,196 to 30,587 (which partly reflected tighter recruiting standards announced in 2002).

The church acknowledged in a 2007 news release its concerns over maintaining activity among newly baptized members, partly because “they feel inadequate to accept a position to serve in the church because of inexperience.” In Mormonism, of course, even routine membership makes heavy demands of time and money. But the church said it has “refined its missionary program to aid in the retention of converts” and quoted Hinckley’s assertion that during his presidency “retention has increased significantly.”

Almost simultaneously, a very different scenario was presented by David G. Stewart Jr., a Nevada surgeon and onetime missionary who spent 15 years analyzing church growth. Though the LDS church membership continues to grow each year, he said, the rate of annual membership growth fell from 5 percent in the late 1980s to less than 3 percent in 2000–2005. Also, the number of baptized converts per missionary fell from 6 or 6.5 in 1985–1999 to only 4.5 per missionary during 2000–2004. Among other points made in his self-published The Law of the Harvest: Practical Principles for Effective Missionary Work:

“Study after study demonstrates a vast discrepancy between official LDS membership claims and participating or self-identified membership.” It is likely that only a third of Mormons on the worldwide church rolls are active, roughly 4 million. “Barely one in four international converts becomes an active or participating member” and “convert retention rates remain very low in much of the world.” “Catastrophic losses” of converts occur shortly after baptism. It appears that within a year of conversion, 75 percent of foreign converts are not regular church attenders, and that 50 percent of U.S. converts are non-attenders.

Globally, Mormonism’s conversion rate is less than that for churches related to the Assemblies of God, Seventh-day Adventist Church, Southern Baptist Convention, other Evangelical and Pentecostal groups, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. The Adventists in particular reported adding 3,176 new members per day in 2000, compared with the LDS addition of 661 converts and 270 children per day in 2004. The LDS church has only a fifth of the Latin American presence of the Assemblies of God, though the latter was founded 85 years later.

Some 85 percent of Saints still live in the Western Hemisphere while only 5 percent of Saints live areas that contain 80 percent of the world’s population. LDS evangelism is particularly sluggish in Africa and the former Soviet bloc, where other denominations are flourishing. In addition, the LDS birth rate is declining significantly not only in the United States but overseas, limiting both the natural growth in membership and the ranks of potential future missionaries.

Stewart proposed a wholesale rethinking of LDS evangelistic strategy. He said missionary tactics by traditional Christian churches are worth examining, even though they “lack the full gospel” and the essential “divine authority” that Mormonism provides. His study suggested that well-versed career missionaries may be more effective than LDS short-termers with limited language and cultural awareness making cold calls. Stewart blamed superficial conversions and dropouts partly on the 1959 strategy of “accelerated baptism” developed by the Apostle and First Presidency member Henry D. Moyle, who urged workers to baptize inquirers as soon after first contact as possible. In Stewart’s view, “marketing tactics” often replaced “scriptural standards.”

Similarly, Young noted that a revised strategy would “allow indigenous expression to emerge,” which is the reason the Mormons’ Evangelical Protestant rivals, with their missiology think tanks, succeed so well in Latin America. The same could be said of Catholic “inculturation” in Africa. In one listing, twenty-three scholarly studies between 1976 and 1992 demonstrated “ludicrous” consequences when “correlation” policies from Utah headquarters were forced on non-American congregations. But these are the sorts of questions raised by the intellectual strategists, with whom the hierarchy has a wary if not antagonistic relationship.

Why must missionaries wear the required uniform of white shirts and dark suits that marks them as outsiders? Cannot those thinly prepared young missionaries be supplemented by more missionaries of Catholic and Protestant style who spend careers deeply immersed in their foreign cultures? Why impose generic architectural plans from Salt Lake on meetinghouses in far-off places? Why must each and every women’s auxiliary lesson be the same for every nation and produced in Salt Lake? Why celebrate Pioneer Day in Bolivia? Why do African wards sing American hymns to the accompaniment of pianos while drums and dancing are forbidden? BYU interviewing for a nationwide study of American black converts found considerable longing for the gospel music they had to leave behind in Baptist churches. Will the Americans atop the LDS power pyramid ever decide that the foreigners, now a majority of the membership, should be the majority among the apostles?

As for the Utah heartland, the Salt Lake Tribune filed a public records request and acquired normally confidential membership counts that the church provides Utah’s Office of Planning and Budget, covering 1989 through 2004. The state population is now only 62.4 percent LDS, with decreases occurring in every county, and based on dropout estimates only 41.6 percent of Utahns would be considered church-going Mormons. Whereas Utah women of child-bearing age averaged 4.3 children apiece in the 1960s, far above the national average, the number had fallen to 2.6, only half a percent above the national average.

One crucial factor for the twenty-first century will be the identity of Hinckley’s successors as LDS president. When a president dies, he is succeeded automatically by the person with the longest tenure as an apostle. So the next leader would very likely be Thomas S. Monson, who has been a member of the three-man First Presidency since 1985. Born in 1927 in Salt Lake and seventeen years Hinckley’s junior, Monson was nearly fore-ordained for the top job in 1963 when President David O. McKay’s administration tapped him as an apostle when he was only thirty-six, the youngest appointee in a half-century. But then, Monson had made bishop at age twenty-two. He was the first World War II veteran to become an apostle, and the first with a master’s degree in business administration, from BYU. His bachelor’s degree in business is from the University of Utah. At the time of his selection, Monson was general manager of the church-owned Deseret Press commercial printing firm, after being the sales manager and an advertising executive with the church’s Deseret News. While an apostle, he also served as president and board chairman of the Deseret News publishing company. Monson, the father of three, is regarded as an avuncular, middle-roading administrator with the public relations instincts of Hinckley but not the high-level skills.

It could be a far different story with the man next in line. Boyd K. Packer cuts a higher profile than Monson and puts more stock in bluntness than in PR. Though a bit older than Monson, having been born in 1924 in Brigham City, Utah, Packer has appeared to exude robust health and could live to succeed Hinckley or Monson. Packer, a B-24 bomber pilot in the Pacific during World War II, earned an education degree at Utah State University, taught high school seminary, and did advanced study in education at BYU. Curiously, the church almanac has for years said he has a Ph.D. though, as www.lds.org accurately notes, his degree is the less academically rigorous Ed.D. He served as assistant administrator of the seminary and institute program, as an assistant to the Twelve Apostles, and as president of the New England mission before becoming an apostle at age forty-five. He is the father of ten.

A Packer presidency could be a crossroads, since he is quite possibly the most doctrinaire of recent apostles and the most likely to enforce an even harder party line and to let the chips fall. Mormon liberals assume that Packer more than anyone else orchestrated the 1990s crackdown on intellectuals and feminists. Ezra Taft Benson was expected to be that sort of president too, but he was eighty-six and in failing health when he took charge in 1985 and was more amenable to his colleagues than Packer might be.

Packer’s worldview was dramatized in a 2004 lecture to lawyers and judges who hold the LDS priesthood. He cited Joseph Smith’s warning to Stephen Douglas: “If ever you turn your hand against…the Latter-day Saints, you will feel the weight of the hand of Almighty upon you.” Packer decried liberal court rulings that foster pornography, disruption of the family, and other moral ills. “I know of nothing in the history of the Church or in the history of the world to compare with our present circumstances,” he stated. “The world is spiraling downward at an ever-quickening pace” and “it will not get better.”

Since his excommunication, D. Michael Quinn has been more willing than most observers to speak freely about Packer’s method and manner. “Packer is combative and willing to go to the mat with the apostles on any issue. They simply acquiesce. If not, every weekly Temple meeting of the First Presidency and the Quorum would be an argument. Howard Hunter [then an apostle and later the church president] told me himself in 1983, ‘I don’t want to turn every Temple meeting into a fight so I don’t say anything,’ referring to apostles he called zealots. Leaders like Hinckley are in a quandary because the smooth operation of the church is impeded if every agenda item becomes a knock-down battle, so they have to pick and choose where to oppose him.” Asked about the prospect of a Packer presidency, a well-informed, liberally inclined Mormon gave a succinct assessment: “Scary.”

(For other apostles in line for the presidency, see this chapter’s Endnotes.)

Many leading analysts of the LDS Church agree that the hierarchical defensiveness, disciplining, and “correlation” are natural responses to exponential growth. The leaders fear that things could spin out of control, and they are more detached from the membership. Moreover, the old familial and friendship bonds count for less in a large, bureaucratized system. A sophisticated analysis of Mormonism’s recent “retrenchment” was provided in The Angel and the Beehive (1994) by LDS sociologist Armand L. Mauss. Earlier in the twentieth century, by Mauss’s account, the General Authorities played down older distinctives, educators made use of outside thinkers, and Mormons generally assimilated with American culture, a process that reached its apex in the 1960s. Certain lifestyle traits (for instance, teetotaling and marrying within the faith) remained. LDS doctrines were regarded as heresies by traditional Christians, to be sure, but America was indifferent to theology and less interested in God’s revelations than in personal fulfillment. Mormons had become so successful in living down their nineteenth-century disrepute that they now faced “the predicament of respectability” and felt the need to reinforce their identity and the boundaries of their subculture.

That predicament has conditioned the leadership’s policies ever since: centralized control, continuing secrecy, regimentation, “correlation,” obedience, suspicion toward intellectuals, suppression of open discussion, file-keeping on members for disciplinary use, sporadic purges of malcontents, church education as indoctrination, the proselytizing push, and reemphasis on religious uniqueness (the centrality of temples and related genealogical work, continuous revelation through modern prophets, understanding the Bible in the light of Smith’s special revelations). Mormonism still desires mainstream status, but largely in order to foster good public relations and proselytism, and in certain cases, alliance with other conservative religious groups to achieve political influence in selected issues.

In the process of retrenchment, some of the church’s best and brightest have become alienated. Quinn remarked from the sidelines that suggestions and complaints from the Sunstone and Dialogue set “will have no effect, because the leadership of the church basically writes off the North American liberals as disloyal…I see Mormonism in for a long Dark Ages.” But he thought that will change as educated leaders from other nations arise to “create a climate internationally that demands a free marketplace of ideas. That may be slow in coming, but I think it’s going to happen.” He did not look for alterations in doctrine (such as women in the priesthood) but believed there may be “fundamental changes in policy otherwise.”

What such liberal interpretations ignore is that Mormonism may appeal precisely because of is authoritarianism. Evangelical propagandists keep trying to score points by demonstrating that the Mormon prophets have changed their teachings. But what matters most to Mormons, perhaps, is not the content of the creed but the confidence with which it is affirmed and reaffirmed. This is, after all, a church that believes in latter-day revelation. As Ezra Taft Benson proclaimed, a living prophet trumps dead prophets. And if Joseph Smith in 1830 could upend several millennia of Judeo-Christian tradition, why could not the Smith of 1844 repeal the revelations of 1830? An evangelistic booklet from BYU said proudly, “Some may see change in the teachings and practices as an inconsistency or weakness, but to Latter-day Saints change is a sign of the very foundation of strength,” namely, that God continues to reveal his will through his church.

What has remained consistent from 1830 through to the twenty-first century is the conviction that God has a latter-day prophet and priesthood through which he uniquely works his will upon the earth. If so, unquestioning obedience is a logical response. And in an age of moral turmoil and 500-channel spiritual choices, many people desire just such decisive leadership.

The Mormon hierarchs can hardly be inspired to loosen the reins if they look over the fence at the experience of other denominations. Conservative Protestant groups that began floating leftward, such as the Southern Baptist Convention and the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, went through virtual civil war when they decided things had gone too far and moved forcibly back to the right. The popes and their American allies have faced great difficulty in attempts to restore an older era’s discipline and keep theologians and colleges in line. Protestant denominations that embraced liberal theological pluralism—for example the United Methodist Church, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Episcopal Church, United Church of Christ, and Disciples of Christ––have suffered drift and decline. The liberalization and resulting confusion in the Smith-related Community of Christ is perhaps most unnerving all.

In conveying a sense of religious authority, the LDS Church is not alone in the marketplace. While Mormons look to Temple Square, myriad Catholics follow the pope, and the most successful variants of Protestantism preach an infallible and trustworthy Bible with answers to the human plight that can clearly be understood by all. The Saints’ wholesome moral living pays off in health and contented lives, but such is the case with other faiths as well. Like the Mormons, the Evangelicals uphold traditional morals and encourage personalized testimonials. And on certain aspects of religion the Saints fall short compared with other groups. They lack the meditative techniques that are so appealing today. Even a mediocre Protestant preacher is bound to present better Sunday sermons than the ward talks from Mormonism’s lay amateurs. The Saints lack the immense intellectual resources found in mainstream Judaism and Christianity and, except perhaps for temple rites, the liturgical and aesthetic richness of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Episcopalianism.

But those religious competitors can learn much from the Mormons. The Saints outshine most in devotion to what they believe. Generous with their time, they also put their money where their mouth is, faithfully tithing for the church and fasting for the needy, even as American society promotes selfishness. While other Americans yield to the demands of youth, adult Mormons impose high demands on their next generation, requiring them to ingest church teaching an hour a day through high school and expecting the boys to save up their own money and spend two years in hard-core mission work. The system produces young adults with pride and commitment.

“This is a story of success,” said Gordon Bitner Hinckley, the Prophet, Seer, and Revelator. “From that pioneer beginning in this desert valley, where a plow had never before broken the soil, to what you see today of this work here and across the world, you can’t reach any other conclusion.” This success is far more than new buildings or convert tallies arising. The Mormon people encircle each other in a loving community, seeking to make sure that everyone has a divinely appointed task and that no one’s needs are overlooked. In modern, fractionated American society, those are accomplishments as impressive as building a city-state on the Mississippi, hauling handcarts across the prairies, or making the arid Salt Lake Basin bloom.