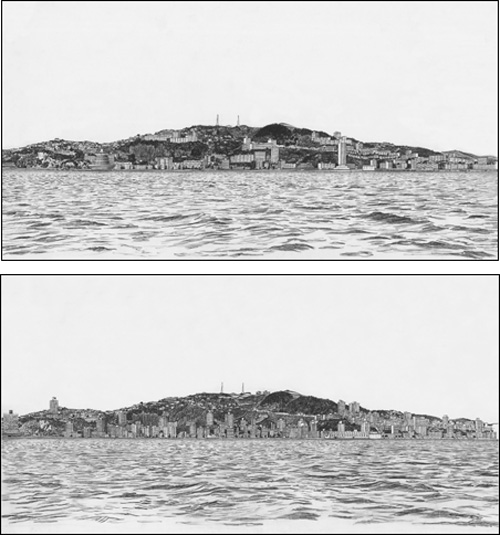

Looking west over the city from Mount Victoria in 1957. PHOTOGRAPH BY B. CLARK, NATIONAL PUBLICITY STUDIOS COLLECTION, NATIONAL ARCHIVES, HELD BY ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, F27590-1/2 (A48317).

By the end of the 1940s, people had grown tired of the rationing and controls that remained in place post-war. They wanted to relax, to enjoy the peace, to take some of Labour’s achievements for granted and to get on with other things.1 As Erik Olssen writes: ‘[P]eople were impatient to return to the domestic certainties which life had so far denied them. For many women and men, marriage, a family, and a house and garden in the suburbs was the consummation of their dreams … . Life had given them more than their share of excitement.’2

Indicative of the general dissatisfaction, Sidney Holland’s National Government was swept to power in the general election of 1949, after fourteen years of Labour. National soon put an end to the rationing of everyday items such as butter and petrol and removed controls on many imports. Other restrictions remained in place. For example, steel and cement – both essential for public and commercial building – continued to be in short supply and their use was restricted until the mid-1950s.3 Increasingly, though, New Zealand enjoyed a period of economic growth and prosperity that lasted until 1967–68: ‘Pushed along by handsome prices for primary products, farm production set new records, group-housing suburbs of young families called for schools and telephones and streets, factories spread, dams rose, trees fell, and over a quarter of the entire national product was thrust into capital formation.’4

Increased car ownership provided access to the new suburbs, with families and individuals also filling their homes with new appliances. Possession of washing machines, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners became widespread in the 1950s and televisions appeared from 1960. The shopping experience was changing – the opening of the first Foodtown supermarket was reported in the August 1958 issue of Home and Building.5 Even housing was ‘caught in a nexus of consumerism’ when clusters of houses were designed, built, stuffed full of desirable items and put on display in the annual Parades of Homes.6

More than ever, the detached house was the desired norm. The new National Government favoured private home ownership over and above state-owned rental housing. The prosperity of the period meant that home ownership was now a viable option for greater numbers of people. In addition, National eased conditions for State Advances Corporation loans and passed legislation allowing tenants to buy their state houses off the government. For men and women who had struggled through the depression and then war, the security of home ownership was consistent with the domestic model to which they now aspired. And the suburbs continued to grow, as did the level of concern about the impact of the suburban sprawl – in particular, the loss of market gardens and agricultural land. In 1959, the Dominion reported that market gardening and glasshouse land in the Hutt Valley had dropped from 500 to 85 acres in the preceding twenty years.7 Hiroshima provided the other worry; the Cold War and the threat of a nuclear disaster lingered in the background as an ever-present insecurity.

From the mid-1950s when the restrictions on the use of steel and cement were lifted, there was enormous government expenditure on public works, from hydro-electric development (and the associated towns like Roxburgh and Twizel) to roads (including the Auckland and Wellington motorways), and individual buildings such as Auckland’s Bledisloe State Building, Wellington’s Bowen State Building, the School of Engineering Building at Canterbury University and the Dental School Building at the University of Otago. National favoured private home ownership but acknowledged that housing was still in short supply and thus maintained a state-housing programme of somewhat reduced public profile. The Housing Division’s output from the 1950s and ’60s is characterised by a variety of house types, from low-density detached and semi-detached houses, through to the high-rise Upper Greys Avenue Flats in Auckland and Gordon Wilson Flats in Wellington, both of which were started in the mid-1950s. By the late 1960s about half of all state housing was medium density (that is, up to three storeys high).8

New tracts of housing in the Hutt Valley in the mid-1960s. PHOTOGRAPH BY WHITES AVIATION LTD, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, WA-65222-F.

With the improved economic conditions, private and commercial work escalated too. A twenty-page Dominion supplement titled ‘Architecture in Wellington 1963’, published in May that year, provides a valuable snapshot of architecture in the capital city mid-way through this period of extensive redevelopment.9 The supplement was compiled by the Wellington Branch of the NZIA to promote modern architecture, town planning and a higher density of housing. Alluding to the title of one of Le Corbusier’s most influential books, it stated: ‘In our city today architects are planning our city of tomorrow.’ While it featured modern houses and recent churches, including Futuna Chapel, the focus was on the city centre, including a proposed civic centre, and new high-rises, both commercial (such as Plishke & Firth’s Massey House, Structon Group’s neighbouring Manchester Unity Building, Bernard Johns’ Wool House, Structon Group’s Racing Conference Building and Stephenson & Turner’s Shell House) and residential (including Porter & Martin’s Clifton Towers and Gabites & Beard’s Hamilton Court Flats). The city skyline was going up. The supplement gave high-density housing a particular push: ‘Various factors make these city flats desirable, including: convenience, value to the owner, cost-saving to the city, conservation of valuable land, personal preference, re-vitalisation of the city’s heart, reduction of potential traffic problems, etc.’10

The north end of the CBD in 1963. The first glass-clad high-rises, including Massey House and Shell House, can be seen. NATIONAL PUBLICITY STUDIOS COLLECTION, NATIONAL ARCHIVES, HELD BY ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, 16099-1/4 (R2842).

Such commissions meant that increasing numbers of public servants were attracted into private practice, leaving the Ministry of Works short-staffed. Recruits were sought from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, but the ministry continued to be haunted by a shortage of qualified and experienced architects and engineers for most of the 1950s and ’60s.11 Some public building projects had to be let out to architects in private practice, creating something of a vicious circle as it tended to encourage more architects out of the public service and into private firms.

To a certain extent the founders and stalwarts of the Architectural Centre countered this trend by remaining in public service, where they moved into positions of increasing authority. They included Gordon Wilson who was Government Architect from 1952 until his death in 1959; Fergus Sheppard who succeeded him as Government Architect; Graham Dawson who was District Architect within the Architectural Division, first in Wellington and then in Auckland; Helmut Einhorn who worked in the Architectural Division from 1953, the Hydro-electric Design Division from 1956 and finally the newly established Environmental Design Division from 1967; and Fred Newman who became the chief architect of the Housing Division in 1956. George Porter was one who left the Ministry of Works, setting up private practice as an architect and town planner in 1952 and then entering partnership with Lewis Martin in 1954, shortly after Martin’s return from overseas. The shortage of experienced staff in the ministry ensured job opportunities for young graduates such as William Alington and James Beard.

Stephenson & Turner’s Shell House (1957–60), said to be New Zealand’s first fully curtained-walled office building. PHOTOGRAPH BY CHARLES FEARNLEY, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, 1/4-075735-F.

With the building boom, those in positions of leadership like Wilson and Cox had less and less time to give to Centre activities. The ministry’s patronage began to wane. By the mid-1950s, for example, monthly meetings were no longer being held at the ministry offices but in members’ houses. Younger staff took up the reins, complemented by individuals from other disciplines and backgrounds. Their input gave rise to new initiatives, notably the publication of a journal and the establishment of a gallery for presenting modern art, architecture and design to the Wellington public. These were formative years for arts journals and non-institutional galleries, and the fledgling ventures had impact and influence. These initiatives also demonstrate both ambition and generosity, with an extraordinary amount of voluntary labour dedicated to achieving the desired ends. The Centre’s entrée into politics followed at the end of the decade.

Porter & Martin’s Aston Towers (1963–64) offered much higher density housing than its neighbours. PHOTOGRAPH BY CHARLES FEARNLEY, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, 1/4-075728-F.

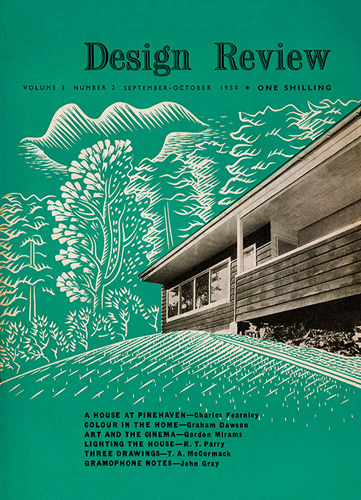

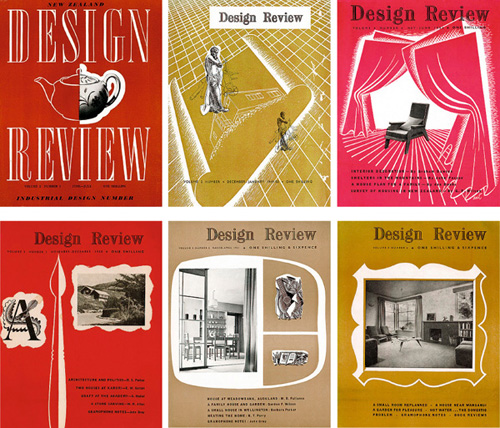

Design Review was published by the Architectural Centre from April 1948 to April 1954. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Paul Walker and Justine Clark

The Centre’s programme of educating the public with Te Aro Replanned and the Demonstration House found a natural extension in its strategy of publishing.1 In August 1947, in the Centre’s second year, a proposal to set up a regular journal was developed and put to the organisation’s executive committee by the first president, John Cox. It would be quarterly, supported by advertising, with Ian Reynolds as its editor. The journal did not get going until the following year, however, with the first issue of Design Review appearing in April 1948. It was less ambitious than Planning, the journal established by Auckland’s Architectural Group in 1946. Planning was impeccably designed: in landscape format, its title in large, lower-case, sans serif letters proudly borne on its otherwise white cover. The layout of each article was likewise modernly spare. The Group’s ambitions were signalled by the inclusion in Planning 1 of an endorsement from Richard Neutra (a prominent Los Angeles architect and office-holder in the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) for their manifesto. But the only Planning issue ever to appear was the first. Design Review, by comparison, appeared on a two- rather than three-monthly schedule till 1954. So while the Centre managed to produce 29 editions of its journal to the Group’s one, conversely the Group designed and built a whole series of innovative houses, while the Centre managed only its Demonstration House.

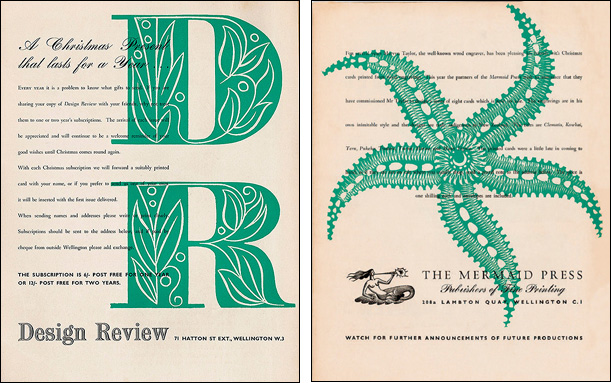

The inside cover of Design Review, vol. 3, no. 2, September–October 1950, featured an advertisement for gift subscriptions to the magazine, and the back cover carried this advertisement for Mervyn Taylor’s Mermaid Press. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE AND THE TAYLOR FAMILY.

Though Design Review was financially never very robust, its inclusion of advertising gave it some viability. The cultivation of a wide audience – at home rather than abroad – also helped. The lead article in the first issue characterised the organisation’s membership as inclusive:

… we of this Architectural Centre in Wellington are a group of architects and draughtsmen and wood engravers and other people whose greatest claim to affiliation is an overriding enthusiasm for good design. Good design entails a rejection of traditional approaches, for their ‘steam has dried up’. A new, New Zealand vernacular approach to design is surmised possibly to be emerging. And since any true vernacular extends beyond the designer and the thing designed to the sympathetic enjoyment by the people for whom it was designed, then we unashamedly burst into print.2

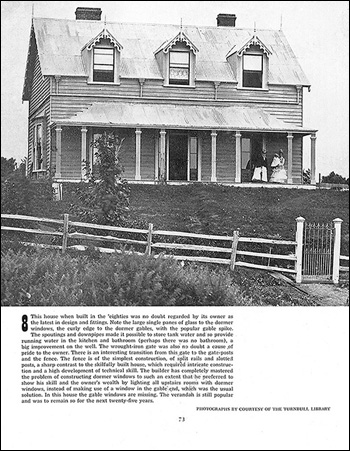

Gordon Wilson contributed a five-part ‘Pictorial Survey of Housing in New Zealand’ to Design Review, discussing developments from Pakeha settlement through to the then present day. This page is from part 2, published in the December 1949–January 1950 issue. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Other articles included a critique of a group of four shops in Naenae (‘a good looking building – in spite of its context’); another on the art of the illustrated book, occasioned by an exhibition at the Wellington Public Library of prints by local artists; and a review of a British Council exhibition of English rural crafts. These articles reveal that the range of interests that the magazine addressed were to extend beyond architecture and to include the fine arts and a broader range of design and related activities. The writers were drawn from an array of design and art disciplines. The cover of the second issue (July 1948) featured William Toomath’s perspective drawing of Te Aro Replanned, with the image of Deborah Kerr collaged onto a balcony in the foreground, perhaps indicating a wish to reach even wider audiences.

If a broad scope of interests was maintained throughout the publication life of Design Review, so was a commitment to design excellence in the magazine itself. A draft letter to be sent to advertisers (undated but probably from 1949) sets this out: ‘In the past little or no consideration has been given to things designed and made in this country. It is the aim of Design Review to arouse and focus design interest on all things made, built or planned in New Zealand. To this end care is taken to maintain a high standard in the production of Design Review.’

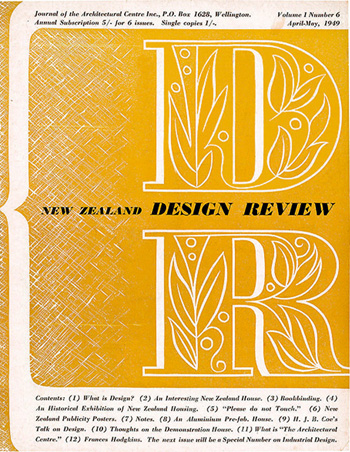

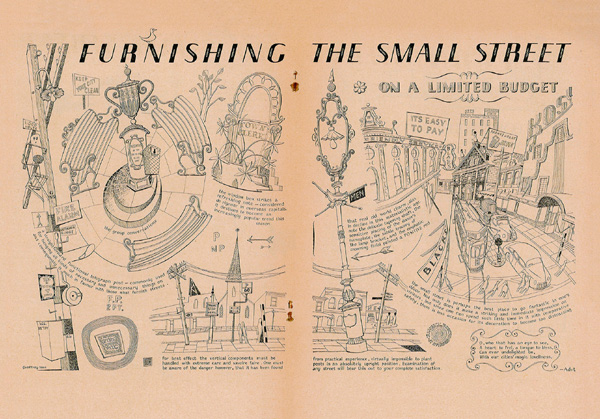

Each issue of the journal was indeed carefully laid out, with generous margins, numerous photographs, and – from the sixth issue onwards – good paper stock. The graphics of the magazine are notable, especially the design and typography of the covers. These feature blocks of (off-primary) colour, a range of graphic devices, and the occasional use of elaborate typefaces, for example, in the florid DR that dominates the mustard-toned cover of issue number 6, the number with which the dominant ‘look’ of the publication was established. While interior layouts are for the most part much more restrained than this, sometimes these too let loose, for example, in a double-page spread in the May–June issue of 1950 headed ‘Furnishing the Small Street’, which featured whimsical sketches in the same Osbert Lancasterish style as many of the sketches in Plischke’s Design and Living (1947).3 Design Review’s indulgence in fruity typography, however, rather suggests the influence of the much-read English journal, the Architectural Review. During the post-war period – under the guidance of its co-editors including Lancaster and the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner – the Architectural Review had departed from the severe discipline of its pre-war look by frequently adopting the use of elaborate Victorian typefaces and the printing of sections on coloured paper stock. This variety was in line with Pevnser’s promotion of the idea of the picturesque: he argued this to be a particularly English aesthetic practice that he believed could be usefully translated from its landscape origins to the contemporary context, and in particular to modern urban design.4 The picturesque revival was part of the Architectural Review’s broader programme of ‘visual re-education’. This was articulated in January 1947, in an editorial on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary,5 and was cited a few weeks later by the acting president of the Centre, George Porter, at the organisation’s first annual general meeting as he tried to describe the Centre’s ambitions: ‘The Architectural Review defines it as “visual re-education”, but though this is certainly a major task I do not think this can be the whole of it. There must be a full integration of all the senses, and a full understanding of cultural values and relations.’6 This intimated, perhaps, a turn to cultural specificity which marked modernism everywhere, including New Zealand, where after the 1940 centennial, architecture, like other cultural fields, was increasingly conscious of its own local history.

Design Review, vol. 1, no. 6, April–May 1949. The graphic design of this issue by Mervyn Taylor established the dominant ‘look’ of the magazine. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Though everyone involved in Design Review undoubtedly shared the same strong commitment to design excellence, it was probably more than anyone else the illustrator and Centre foundation member Mervyn Taylor who was responsible for the journal’s characteristic style that emerged in the second year of publication.7 This was quite different to the – by then – rather conventionally avant-garde minimalism of Planning, and different also to the dowdy and amateurish design and production values of the country’s main architectural publications at that time, Home and Building and the Journal of the NZIA. The former at this period was characterised by scrappy layouts and poorly reproduced images, and the latter by its very conservative layout and lack of any images at all. Design Review quickly earned a deserved reputation as the best New Zealand publication in its field.

The centre spread of Design Review, vol. 2, no. 6, May–June 1950, featured a drawing by Geoff Nees titled ‘Furnishing the Small Street’; its whimsical qualities recall the drawings of the architectural writer Osbert Lancaster. Lancaster was a co-editor of the Architectural Review, the venerable English journal from which, in several respects, Design Review appears to have taken its lead. COURTESY OF THE NEES FAMILY.

Design Review covers. For most of the journal’s life, its covers had a robust graphic look. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Design Review covers. For most of the journal’s life, its covers had a robust graphic look. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Keeping Design Review afloat was nevertheless difficult. The first issue was distributed free to members of the Centre, and put together through the voluntary efforts of editor and contributors. Editorial responsibility for the second issue switched from Reynolds to Howard Wadman, playwright and editor of the Yearbook of the Arts in New Zealand, with George Porter and Helmut Einhorn as associate editors. It was priced at 9d, or 3s for a yearly subscription. Wadman soon departed, and Taylor was made art editor. The cover price increased to 1s. Despite this and the voluntary nature of much of the labour and time needed to put the magazine together, the Centre’s losses kept accumulating. It was decided that the magazine should be produced privately. Taylor was contracted to produce the six issues of volume 3 for a fee of £50. G. L. Gabites edited the journal with Taylor and a board of associates including Plischke. A chatty column called ‘Here and There’ was introduced; the pseudonym under which it was produced – the picturesque term Sharawag – underlined the influence of the Architectural Review, which had been responsible for reintroducing such quaint anachronisms into contemporary architectural commentary.

Perhaps in an attempt to broaden readership, another introduction was a regular column of gramophone notes, and the range of topics in feature articles expanded to include cinema (a piece by John O’Shea in July–August 1950), architecture and politics (November–December 1950), Greek coins (September 1951–May 1952) and Japanese architecture (June–July 1952). To accommodate this new material, the magazine increased in size to about twenty pages per issue.

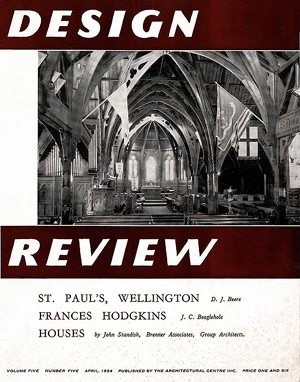

Despite these changes and another increase in subscription rates, losses continued. A grant was secured from the Department of Internal Affairs to continue, but this support was withdrawn in 1954, and Design Review folded with volume 5, number 5. A critique of an exhibition of recent New Zealand architectural work, held at the National Art Gallery and arranged by the Wellington Branch of the NZIA, complained of the prosaic nature of the design on show: ‘one was conscious of a lack of bravura, of boldness, of the ridiculous even’.8 These criticisms could have been directed at the last issue of Design Review itself. It had again been redesigned, but – the cover especially – lacked the verve that had often been shown in the past.

The cover of the last issue of Design Review, vol. 5, no. 5, April 1954, featured Old St Paul’s, Wellington, and a new graphic look. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Nevertheless, the last number of Design Review constitutes a good measure of where the energies and enthusiasms of the members of the Architectural Centre were then refocusing. The cover story was about the Wellington cathedral now known as Old St Paul’s,9 a building over whose preservation the Centre was to campaign long and hard in subsequent years. Another feature was a lengthy article about Frances Hodgkins, covering the opening address of J. C. Beaglehole on the occasion of an exhibition of her work at the Architectural Centre Gallery. The gallery, rather than Design Review, was to become the venue for the Centre’s public voice in subsequent years.

Design Review was not the Centre’s last attempt at a major publishing venture. It next tried a book. From 1957 to 1960 Centre members and their colleagues throughout New Zealand expended much effort collecting and preparing material for a book on New Zealand architecture that would take its cue from G. E. Kidder Smith’s Sweden Builds (1950), Switzerland Builds (1950) and Italy Builds (1955), in turn based on Philip Goodwin’s Brazil Builds of 1943 (for which Kidder Smith supplied the photographs). Tentatively titled ‘New Building in New Zealand’, it was more commonly known simply as ‘the book’. ‘The book’ intended making ‘first-class’ examples of New Zealand architecture available for the ‘delectation of New Zealanders and those abroad’.10

While ‘the book’ never made it to press, the project throws light on the state of play in New Zealand architecture in the late 1950s (as analysed in Looking for the Local: Architecture and the New Zealand Modern). By 1957, certain positions as to what New Zealand architecture could or should be had been consolidated in print: in various writings for the 1940 centennial; in the Group’s manifesto and the single number of Planning; in Plischke’s writings, particularly Design and Living; and, much more inclusively, in the Centre’s own Design Review.11 Centre members saw an opportunity for a different kind of publication: one which would showcase the buildings they and other young architects had made in the optimistic post-war environment. Those who had founded the Centre as students and fledgling architects were now established practitioners – some with English training, some with American postgraduate degrees. They set out to document all that had happened: the architecture that they and their contemporaries had made. In a country in which little had been built, they felt there was some very good architecture indeed. This architecture was of New Zealand and its particular characteristics were as vital as those anywhere.

The proposed publication was also unlike its local predecessors in that it was intended to reach further. Where earlier books and journals had been predominantly concerned with educating the New Zealand public as to the value of modern architecture and design, the New Zealand architecture collected in ‘the book’ was to be made available for international consumption. With this project New Zealand architects understood themselves as part of, and able to contribute to, international architectural culture.

The cover of the Architectural Review, October 1959, ‘Commonwealth I’, the special issue of the journal on the architecture of the Commonwealth ‘dominions’ for which Nikolaus Pevsner collected material in New Zealand in 1958. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW.

The Architectural Press, English publishers of Kidder Smith’s books, was approached to publish the Centre’s.12 They declined. But not long after this, a kind of vindication came for the view that New Zealand architecture could interest an international audience. In 1958, Nikolaus Pevsner toured New Zealand to give lectures for the University of New Zealand with the sponsorship of the British Council.13 But he was also on the lookout for material to publish in the Architectural Review, in a special issue on architecture in the Commonwealth that appeared in October 1959. New Zealand architecture could be seen internationally but only when tied to the new manifestation (the Commonwealth) of the old Empire. Pevsner’s time in Wellington was organised by the Centre; he was enlisted in a number of the Centre’s ventures, notably in the effort to get the Architectural Press decision rethought.14 In turn the Centre prepared a shortlist of 35 buildings for his forthcoming Architectural Review special edition and obtained photographs from which the editors would make a final selection.15

The Centre also supplied an essay, penned by Lewis Martin, on the New Zealand building industry. All this was understood as ‘preliminary work’ for ‘the book’: it was hoped that the written material could be reused; that the buildings shortlisted would form the nucleus of ‘the book’; and that the special issue would kindle international interest in New Zealand, thereby making the publication of ‘the book’ viable. But perhaps the fact that Pevsner’s version of New Zealand architecture – based on the cursory familiarity of a six-week visit – was published while in the end the Centre’s was not suggests an important point that is pertinent still. Even though there was a wide perception in the post-war years of the value and legitimacy of regional variations of modern architecture, these were constructed through complex exchanges between region and centre where cultural agency was not equally distributed. Acknowledgement of the quality of modern architecture outside the metropole did not reduce the metropole’s authority to adjudicate: New Zealand architecture was presented to an international audience not on its own terms, but rather on those of Pevsner and the Architectural Review.

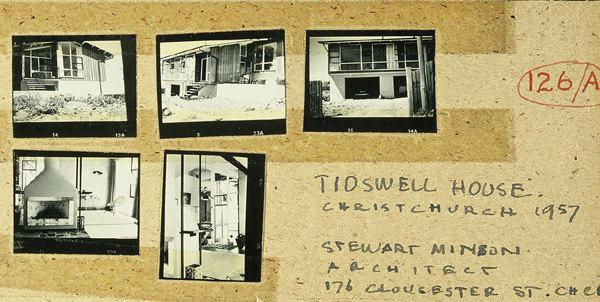

The Architectural Centre’s book project was predicated on the belief that New Zealand was on the eve of a great deal of building, and that it would be helpful to document what had been achieved in the modernist venture thus far. The book project, then, was at least at its beginning concerned not with prescribing what New Zealand architecture could or should be, but instead with presenting what it was and what it had become. To this end, the team involved in ‘the book’ devised a scheme to produce a national survey of good, contemporary architecture. Over almost three years of sporadic work, documentation of around 200 projects – mostly in the form of annotated photographs – was collected. It was gathered with the help of district collectors who were requested to list, in order of merit, ‘significant modern buildings’ in their area. This process of accumulation suggests that New Zealand architecture was to be discovered out there, in the field, in a disinterested empirical inquiry. However, the way in which the collection of material for ‘the book’ actually unfolded, and the internal debate within the Architectural Centre regarding its editorial direction, also belie certain attitudes to the making of ‘New Zealandness’. These suggest that it would not merely be found, but that it had to be projected.

Not all architects practising in New Zealand agreed with this search for national identity. For example, Ernst Plischke, the most eminent of the European émigré architects, expressed concern about the nationalism of young architects on a number of occasions. He wrote in Design Review in 1950: ‘Sometimes I read articles or listen to people discussing the growth of an indigenous New Zealand style for houses, saying that it should be fostered and strongly supported. But I never know quite what to think – I feel uneasy and wonder what is really meant by it. In the back of my mind I cannot forget how this word indigenous has been misused by reactionaries all over the world. On the other hand I am fully aware of the core of truth in it and the importance of the problem.’16 Neither side in the debate around ‘the book’ entertained such doubts, however. They did not dispute the issue of whether or not there was a specifically New Zealand modernism. Rather, the question was in what manner it should be articulated and represented.

The ‘New Zealandness’ to be manifested in ‘the book’ had to be constructed – just like the buildings themselves – with the materials at hand, in this case photographs of buildings. Did all buildings have this characteristic, or only the ‘first rate ones’, or was it something that existed in the collection as a whole rather than the individual buildings? On the one hand, it was expected that ‘the book’s’ content would arise out of the material found: ‘The relevant emphasis given to houses, commercial work, industrial work etc. will depend entirely on the amount of first class material available in the various categories’.17 On the other, the organisers had certain ideas about what they were looking for, ideas which were not always fulfilled: ‘The general impression about the collection is that they tend to be very much the latest and cleverest stuff, full of clipped verges and windows going up into gables etc. We think this book will cover the last 20 years. Isn’t there anything else that’s very good even though not very recent? And aren’t there any less architectural things – bridges, ski-lifts, silos?’18

The material gathered together for ‘the book’ now sits in archival boxes in the Alexander Turnbull Library. Following the pattern of Kidder Smith’s books, most of the projects are arranged according to building type. The collected images are of varying quality. Some were taken as quick snapshots not intended for publication; others were by professional photographers such as Barry McKay and Sparrow Industrial. But despite this variety there are a number of characteristics shared across these photographs. Many are relatively abstract, dynamic shots, dramatically lit, often showing only a part of the building. There is little occupation and where there are people they are carefully posed. Many of the photographs are in the tradition of modernist architectural photography exemplified by such international figures as Ezra Stoller and Julius Shulman. They suggest certain ways of looking at and thinking about New Zealand architecture.

A typical record gathered by the Architectural Centre from around New Zealand for its book project. Tidswell House, Christchurch (1957), designed by Stewart Minson. ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE COLLECTION, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, PA COLL-811.

The most important of these is typological. This is apparent in a major change in direction that was suggested for the book project about eighteen months after it was started, in December 1958, when a significant amount of material had been collected. Allan Wild explicitly argued that ‘the book’ should not simply be reportage: it should be an evaluation of what New Zealand architecture was.19 Wild wrote that it ‘should be lively and stimulating, controversial, forthright in opinions, assured of being widely reviewed and discussed … . It should not be tatty or chatty or women’s magazine-ish, but blunt like Corb without his occasional incomprehensibility … . But New Zealand and getting evident satisfaction in showing the contributions we have made to architecture, the various clearly defined directions we are taking.’ ‘The book’, Wild argued, needed a theme, and this theme should be dramatised. He proposed a focus on low-cost houses which, he noted, Pevsner had already singled out as the country’s best work.20 (In fact Pevsner had regretted that this was the only work young architects had the opportunity to do.) Wild, who publicly criticised the Architectural Review special issue when it came out, was here invoking Pevsner’s suggestion that ‘New Zealandishness’ might be found in the use of timber and in well-planned houses for clients with small budgets. This field, Wild suggested, was particularly New Zealand’s, ‘whereas’, he wrote, ‘in other fields we merely follow overseas models … our ordinary houses are the best in the world’.21

Others involved in the book project rejected Wild’s view, and by May 1959 there were two book outlines, one drafted by Lewis Martin, the other an alternative developed by Wild. The photographed buildings and their relation to text played a key role in these differing views. In one they were the means through which ‘New Zealandness’ was to be discovered and they would be the key way of showing it; in the other they would be selected to illustrate a particular idea of New Zealand architecture that had already been discursively constructed. This construction was around the house.22 The difference in the positions was subtle – after all, a survey would indeed discover a lot of good houses – but it was nevertheless insurmountable: ‘the more it was discussed the more firmly the two groups held to their own views. Each saw the question as all important; from the point of view of personal satisfaction for those doing the work, of economic success, of practicability and of the Centre’s duty.’23

Wild proposed changing the strategy for ‘the book’ shortly after meeting with the Auckland collectors Ian Reynolds and Bill Wilson, who had not yet supplied material.24 It could be suggested that the proposed re-orientation was heavily influenced by Auckland interests, and in particular the house-oriented ideology of the Group, in which Wilson was the central figure.25 The idea that there was an emerging culture of New Zealand architecture or design more broadly was a motivating idea when Design Review started. But where Design Review could afford, and indeed encouraged, contradictory opinions, ‘the book’, it seems, could not. The aim of presenting New Zealand work to an international audience in a single book certainly required a coherently developed and articulated idea of what New Zealand architecture was. Representation is always a political issue. There are perhaps also regional politics involved in the vying constructions of local identity. One effect of the failure to produce ‘the book’ has been the consolidation of a position as to what New Zealand architecture was and is that has continued to be powerful precisely because it has never been dispassionately articulated. The emphasis on private houses made from timber has become, by default, the accepted view of the period. Had Martin’s strategy prevailed and a book based on it been published, we may have had an alternative version of New Zealand architecture, one, for example, that included not only houses but also building types associated with the urbanism on which much of the Centre’s activities had focused from its inception.

By June 1960 the book project had folded. The Centre was also now deeply involved in other local representations of a much more overt and active nature. Centre members were increasingly occupied with Wellington city politics. The old Centre concerns of ‘striving for a more suitable environment for living’ took precedence over the publication of international representations of national identity. That is, the Centre withdrew from the project of representing and thereby defining New Zealand architecture and concentrated on addressing immediate local issues through local processes.

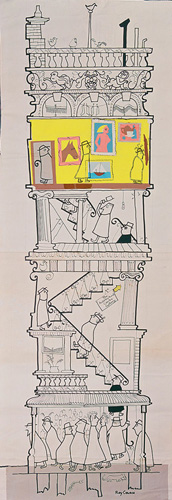

Roy Cowan’s sign for the Architectural Centre Gallery, directing visitors up. MUSEUM OF NEW ZEALAND TE PAPA TONGAREWA, F.6432/11.

Damian Skinner

As outlined in earlier chapters, the Architectural Centre’s aims extended from architecture and design to the arts in general, and the society attracted a diverse membership including artists and collectors of fine and applied art. Its 1946 constitution was explicit in stating its intention ‘To promote a true understanding of the Arts and Sciences among the community’,1 and to this end, from 1953 to 1968, it opened and ran a gallery. The Architectural Centre Gallery, renamed the Centre Gallery in 1960, echoed and extended the proselytising role of the Centre itself, enhancing public ‘knowledge of … design principles in general’.2 More explicitly, it aimed to ‘display stimulating and experimental work in any medium – drawings, paintings, sculpture, pottery, fabric printing, weaving, metal work, etc.’,3 by established and emerging artists, both local and from overseas, and in doing so it effectively took on the role of a public gallery.

The Architectural Centre Gallery opened on 15 June 1953, in leased space on the second floor of 288–290 Lambton Quay. Its inaugural exhibition comprised paintings and drawings by Centre members.4 Subsequently, it showed a combination of ‘rent’ and ‘non-rent’ exhibitions.5 Non-rent exhibitions were organised by those who ran the gallery, and were seen to have public merit. Rent exhibitions featured invited artists who paid rental for the gallery space as well as a percentage of the income from any sales.6 The gallery’s principal revenue came from such shows, complemented by hiring out the gallery in the evenings, admission fees on some exhibitions and grants from the Department of Internal Affairs.

From its inception, the Architectural Centre Gallery maintained a vigorous and diverse programme of local and international art. Overseas exhibitions included the work of Dürer, Matisse, Picasso and Rembrandt; eighteenth-century Japanese artists; nineteenth-century Viennese painters; and contemporary Canadian art.7 The local selection was equally impressive: in 1953, Frances Hodgkins, and the Thursday Group (a local Wellington collective dedicated to life drawing); in 1954, Toss Woollaston, Rudolf Gopas, Russell Clark, Don Peebles and William Mason; in 1955, Dennis Knight Turner, Louise Henderson, Stewart Maclennan and T. A. McCormack; in 1956, Avis Higgs, Sam Cairncross and John Drawbridge; and in 1957, Helen Stewart, John Holmwood, Alison Pickmere, Charles and John Tole, Gordon Walters, Brian Brake, Bruce Henry and John Zambelis.8

The Architectural Centre Gallery was not the earliest alternative to the National Art Gallery and the New Zealand Academy of Fine Art in its emphasis on ‘experimental’ art. The pioneering modernist dealer gallery was the Helen Hitchings Gallery, which opened in 1949. Amid furnishings designed by Ernst Plischke, Hitchings exhibited a range of media, and gave exhibitions to a number of significant artists, including Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston, Eric Lee-Johnson, Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, Juliet Peter, Avis Higgs, Gordon McAuslan and John Drawbridge. It closed in 1951, when Hitchings left New Zealand for Europe.9 Earlier, but more informally, a small number of coffee lounges had displayed art. The best known of these, the French Maid Coffee House, held its first show in 1940 and continued to exhibit artists including Theo Schoon, Sam Cairncross, Gordon Walters and Colin McCahon until it too closed in 1951.10 Others continued where it left off. For example, Elva Bett recalls that Harry Serensin held exhibitions in his coffee bar above Parsons Bookshop in Massey House after it opened in 1957.11

Louise Henderson exhibition in the pioneering but short-lived Helen Hitchings Gallery in 1949. PHOTOGRAPH BY BRYAN D. FRY, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, F145152-1/2.

The French Maid Coffee House on Lambton Quay, with art works on the walls. PHOTOGRAPH BY LEO MOREL, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, ARTHUR DICK SINGLETON PAPERS, MS-PAPERS-1977-01.

The Kate Coolahan-designed invitation to the opening of New Zealand Abstracts. KATE COOLAHAN COLLECTION.

The gallery most comparable to the Architectural Centre Gallery was the Willeston Gallery, owned and operated by Graeme Dowling from the early 1950s (it seems to have been an extension of Dowling’s picture-framing and fine art reproductions business, G. W. Dowling Ltd).12 The Willeston Gallery and the Architectural Centre Gallery both held exhibitions by artists who might not have been accepted by more conservative institutions such as Leonard Mitchell’s Lambton Galleries, which opened in 1954, or the McGregor Wright Gallery, which also represented more traditional artists. Such was the compatibility of the two institutions that in the late 1950s, the Architectural Centre suggested that its gallery might merge with the Willeston Gallery, creating one progressive institution dedicated to the exhibition of ‘experimental’ art in Wellington.13

In 1958, after five successful years of operation, the Architectural Centre Gallery increasingly saw benefits in establishing its own identify, separate from the Architectural Centre, to consolidate and broaden its role as an institution dedicated to the visual arts.14 This happened in 1960 when the lease on 288–290 Lambton Quay expired and the gallery moved to 244 Lambton Quay, to spaces made available by the closure of Lambton Galleries.15 The gallery used this opportunity to change its name to the Centre Gallery, Inc. The new identity was intended to promote the facility ‘as in effect a civic art gallery’, with enhanced activities including better presentation and publicity of exhibitions, ‘original research work’, the maintenance of an art library, and the establishment of a magazine ‘to provide information on activities and exhibitions at the gallery and elsewhere in Wellington and other centres’.16

In its new premises, the Centre Gallery continued to bring Wellington audiences a range of international and locally focused exhibitions, both rent and non-rent, beginning with the New Zealand Abstracts Exhibition in June 1960. That year, it also showed Goya’s Los Caprichos suite of etchings (toured by the Auckland City Art Gallery), a UNESCO exhibition titled The History of Watercolour Painting, and work by Woollaston, Edward Bracey and W. A. Sutton; while 1961 saw a group show in conjunction with the Festival of Wellington, a display of C. D. Barraud watercolours, and exhibitions featuring Rita Angus, Helen Stewart, Helen Mason, Juliet Peter, Roy Cowan and William Mason. In sum, the Centre Gallery continued to bring quality art to the Wellington public.

Of primary importance to understanding the Architectural Centre Gallery is the relationship it established between modernist art and architecture. Central to both was ‘good design’.17 Following the teachings of the Bauhaus, the Architectural Centre sought to unify art, craft and science, formulating a coherent approach in which aesthetic observations would be relevant to, and informed by, those arising from scientific fields of endeavour. Art was central to the broader, unified field that the Centre was determined to influence.

This helps to explain the gallery’s programme of showing a diverse range of media and disciplines, including architecture, craft and industrial design.

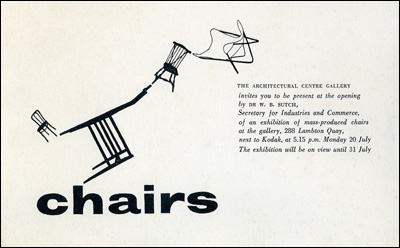

The Geoff Nees-designed invitation to the opening of Chairs. NEES FAMILY COLLECTION.

In 1954, the retail firm Stocktons put on an exhibition of ceramics (including Lucie Rie and Hans Coper pots), furniture, fabrics, glassware and lamps – all intended ‘to illustrate design’.18 An exhibition of advertising art, organised by the Wellington advertising agency Carlton-Carruthers du Chateau & King Ltd, opened in 1955, while a show of Navajo and Mexican rugs owned by W. B. Sutch, and the New Zealand Studio Potters Second Exhibition, organised by Geoff Nees, both took place in 1958. Nees also curated an exhibition of chairs in 1959, hanging a range of design exemplars from the gallery ceiling at eye level.19 Kate Coolahan recalls an even more unusual display of Austrian bread, in which loaves were fumigated and sprayed with lacquer before being hung on the walls.20

Often, group exhibitions combined a variety of art forms. In 1958, Helen Mason and Joan MacArthur exhibited pottery and painting; in 1961, Mason, Susan Skerman and architect Martin Hill showed pottery, fabric and furniture, and Juliet Peter, Roy Cowan, and William and Maureen Mason showed pottery, painting, lithographs and printed fabric; in 1965, Doreen Blumhardt and Brian Carmody displayed pottery and paintings; and in 1966, an exhibition titled Centre Gallery at the Display Centre brought together paintings, pottery, sculpture and fabrics.21

The diversity of media displayed in the Architectural Centre Gallery was not unique, but reflected the wider influence of the Bauhaus and the changing relationships between artistic disciplines in the 1950s. The change in gallery attitudes is consistent with Francis Pound’s suggestion that the context for painting began to move from the literary environment, which fostered the first modernist experiments, to the arena of architecture, which, as New Zealand art began to embrace more varied modernist styles, seemed better suited to accounting for these developments.22 Home and Building developed as a site of commentary and criticism for modernist art alongside Landfall; and architects began to play the role assumed previously by the literati as supporters and patrons of artists pursuing modernist agendas.

Different media were brought together in group shows, as seen here with paintings by Roy Cowan, ikebana by Margaret Scott and, on the right, a sculpture by Margaret Moodie. PHOTOGRAPH BY MAX COOLAHAN, KATE COOLAHAN COLLECTION.

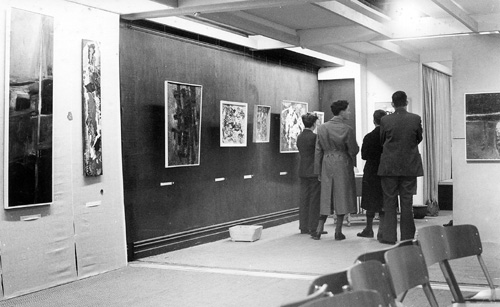

The architectural context out of which the Architectural Centre Gallery arose was highly sympathetic to modernist art practice. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s artists like Don Peebles, Melvin Day, Gordon Walters, Helen Stewart, John Drawbridge and others presented work that was, if not always completely abstract, then at least ‘experimental’, to borrow the Architectural Centre Gallery’s own term. Epitomising the gallery’s commitment to abstract art, in 1958 it decided to exhibit the British Abstract Painting exhibition toured by the Auckland City Art Gallery. Its original destination, the National Art Gallery, refused the show, deeming it ‘a collection of works of a particularly extreme section of ultra-modernism in art’ and warning audiences not to be ‘fooled by what is merely extravagant and grotesque in art’.23 The premises of the Architectural Centre Gallery were relatively small and it appears that the paintings were displayed in a kind of revolving hang, so that by the end of the period, all the works had been on show.24 This and the other instances of abstraction at the gallery support the notion that the realm of architecture provided a fertile field for the propagation of modern art in New Zealand.

The Architectural Centre Gallery had an ongoing commitment to international art, producing a surprising number of shows that sought to introduce local audiences (and artists) to the developments and high points of modernism from other countries. The international focus was not that unusual in itself, as other galleries also began to accept and organise international shows in the 1950s. The Auckland City Art Gallery is a case in point, and many of the exhibitions at the Architectural Centre Gallery and Centre Gallery came from this source. Yet when the self-sustaining nature of the gallery is considered, and its dependence on income from sales, rent and sporadic grants, it is remarkable that it organised and displayed so many international exhibitions. The Architectural Centre Gallery also showed a much wider range of international modernism than say, the National Art Gallery, with its penchant for realist British art.

The reasons behind the Architectural Centre Gallery’s international exhibitions are many. Its audience was comparatively international, including strong elements from Wellington’s émigré communities and the diplomatic corps. International shows were also an expression of the gallery’s didactic purpose: its need to educate its audience about modernism and contemporary developments in art. Seeing New Zealand art against international art had definite benefits for both artists and gallery audiences, stimulating debate and discourse. But more than this, the gallery’s commitment to international exhibitions demonstrates its belief that it was ‘in effect a civic gallery’, presenting modernism to the Wellington public. ‘Our nearest rivals, but not very near, are the National Art Gallery’, wrote W. B. Sutch in 1954, a comment that clearly expressed what kind of institution the Architectural Centre Gallery believed itself to be.25

To hold regular international exhibitions, then, was to achieve a number of things. It was to create and maintain a certain level of status as an institution capable of being a player in an international circuit of art, thus distancing itself from dealer galleries and other less outward-looking organisations. It was, too, in the case of an exhibition like British Abstract Painting, a way of representing its differences from the National Art Gallery, signalling an allegiance to modernist art and literally emphasising its own importance by assuming a burden intended to be carried by a public gallery.

In a larger sense, the international exhibitions at the Architectural Centre Gallery educated Wellington audiences about modernist art and theories. Examples included Conflict of the Twenties: A Period Expressed in Original Etchings, and Lithographs by German Artists, from the collection of émigré Alphonse P. Blaschke; exhibitions of reproductions of Matisse; a show called Recent European Art, with reproductions of Braque, Degas, Léger, Manet, Matisse, Miró, Modigliani, Rouault, Utrillo and Vertes, from the National Library Service; a number of Picasso exhibitions, featuring both reproductions and original works; Viennese art owned by émigré architect Fred Newman; a display of Canadian art; Contemporary British Drawings; and an exhibition titled Twentieth Century Art, which comprised works by international artists in New Zealand collections, both public and private.

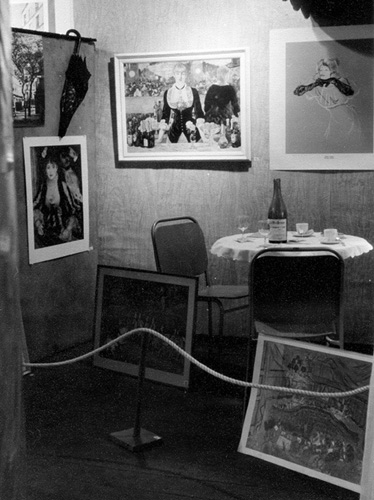

The Architectural Centre Gallery often utilised reproductions in its exhibitions, sometimes solely and sometimes in conjunction with original works, to more fully present a particular artist’s work.26 Yet, while receiving much of its modernism ‘second-hand’, so to speak, the gallery worked hard to ensure a context for its art, whether originals or reproductions. Paris Through the Eyes of Her Artists, for example, held in April 1956, included a Parisian environment for the display of photographs, prints, posters and books, with ‘a typical Seine-side print shop’ and ‘the inevitable Paris kiosk, pasted all round with gay and colourful posters’.27 It was highly inventive. Conflict of the Twenties was also enriched through the inclusion of contextual information. Of it, W. B. Sutch wrote: ‘This success was due primarily, of course, to the material displayed, but the method of display, the information conveyed and the philosophy explaining the social aspects of the German art of the 1920s were all contributing factors.’28

Paris was recreated in the 1956 exhibition Paris Through the Eyes of Her Artists. PHOTOGRAPHER NOT KNOWN, EINHORN FAMILY COLLECTION.

The reliance on reproductions resulted from New Zealand’s distance from the centres of production. But the prevalence of reproductions also signals a desire to partake of the modern – to be engaged with international discourses of art – no matter how outdated or behind contemporary art practice New Zealand really was. And alongside the reproductions, there was in private Wellington collections a small stock of original art works by international artists – notably in the collections of émigrés who brought art with them when they arrived – and the gallery drew upon these on more than one occasion. These inclusions indicate that part of the gallery’s constituency not only had some knowledge of international art but also that their desire to see it here led them to reconstruct the very culture from which they had come, or of which they had partial experience. The art works featured in Twentieth Century Art, for example – a mobile and stabile by Alexander Calder, a sculpture by Henry Moore, lithographs by Fernand Léger and Joan Miró, and paintings by Graham Sutherland, Keith Vaughan and Robert Colquhoun – point to a more sophisticated knowledge of international art than we tend to believe existed in New Zealand, and suggest that an active, rather than passive, interaction with modernism was possible, even from New Zealand.

The notion that the Architectural Centre Gallery played the role of a pseudo public gallery within the Wellington art scene warrants further discussion. An awareness of this role was in place by 1960, when the Centre Gallery’s independence from the Architectural Centre was formulated as an opportunity to promote the gallery as a ‘civic’ institution. Indeed, the other functions listed for the gallery – the curation of special exhibitions, the coordination of original research work, the maintenance of a library and the publication of a magazine – all reflected the expectations of a public gallery, and how such an institution should promote art.

Paintings by Don Peebles adorn the walls, with chairs put out for a lecture or floor talk. PHOTOGRAPH BY MAX COOLAHAN, KATE COOLAHAN COLLECTION.

Exhibition designers experimented with floating curtains to divide space. PHOTOGRAPH BY MAX COOLAHAN, KATE COOLAHAN COLLECTION.

The exhibitions the gallery took from other institutions, most notably the Auckland City Art Gallery, also suggest that it was effectively viewed by others as a public institution. In 1957 the Architectural Centre Gallery showed Costume and Daily Life, toured by the Auckland City Art Gallery; in 1958, Auckland passed on British Abstract Painting, a Picasso exhibition of 80 aquatints and lithographs, and a large show titled Contemporary British Drawings; and in 1959, Contemporary Coloured Lithographs and Silkscreen Prints was again organised and toured by the Auckland City Art Gallery. Correspondence between the galleries reveals that they each viewed the other as suitable counterparts. For example, a letter from Peter Tomory, director of the Auckland City Art Gallery, to the Architectural Centre Gallery regarding the Picasso exhibition of aquatints and lithographs, reads: ‘As only two galleries other than Auckland will be included in the tour, I am giving you first offer on this exhibition.’29

Other evidence of public gallery status includes the 1966 exhibition Centre Gallery at the Display Centre, which was organised by Avis Higgs, Muriel Moody and Margaret Brooke-White to celebrate the Queen Mother’s visit to New Zealand. According to Higgs, the Display Centre was filled with a range of exhibitions, all designed to demonstrate the quality of New Zealand manufacturing, industry and culture to the visiting dignitaries, and it constituted an official event.30 Further, the gallery functioned ‘as an extension of such cultural centres as the Turnbull Library, the National Art Gallery, and art galleries of other centres’.31 The Turnbull Library was the originating force behind at least three exhibitions – a display of nineteenth-century colonial images, Emily Cumming Harris’ botanical illustrations and C. D. Barraud’s watercolours – while the National Art Gallery’s collection was borrowed from on at least two occasions.32

While the case for thinking of the gallery as a public institution is reasonable, it perhaps overlooks the essentially weird nature of the gallery, its ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude, a product of minimal funding and reliance on volunteers to keep it functioning. Throughout the 1950s the gallery committee was spearheaded by W. B. Sutch, an economist who became Secretary of the Department of Industries and Commerce in 1958.33 By all accounts a charismatic man, Sutch would coordinate the exhibitions, assigning individuals the responsibility of undertaking the necessary research and organisation. Doreen Blumhardt emphasises the focus on quality and professionalism: ‘Bill [Sutch] and I often discussed who would be the best person, who would be the best expert to select this exhibition or that exhibition … . This was one of the things that the Architectural Centre [Gallery] always stood for: you get an expert. You don’t take your amateur. That it had to be run on professional lines … . both of us emphasised the importance of professionalism.’34 One of Sutch’s letters of ‘commission’, sent in March 1954, reads thus: ‘This is to tell you that at the last meeting of the Gallery Committee it was decided to ask you four to be charged with the responsibility of doing the preliminary work for the Japanese Exhibition which is firmly set down for early June, 1955.’35 Kate Coolahan remembers that researching an exhibition was often a learning exercise, involving such activities as finding out about new artists or traditions, acquiring import licenses (if necessary) and taking out insurance.36

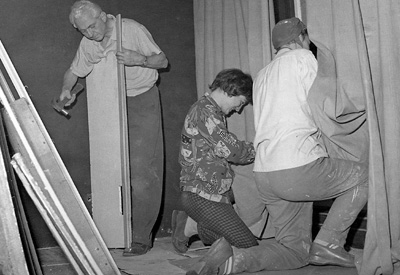

In the do-it-yourself tradition – Alphonse Blaschke, Ann Munz and Juliet Peter setting up an exhibition at the gallery. PHOTOGRAPH BY KATE COOLAHAN.

The gallery did not have professional curators, or even a full-time director until the 1960s. All work was voluntary, from Sutch’s job down to the role of supervising the exhibitions when the gallery was open to the public.37 The heavy reliance on volunteer input was not always a liability, however, for it seems to have been one of the ways in which the gallery was able to maintain – and justify – a distinction between itself and the emerging network of dealer galleries that sprang up in the 1950s; a distinction that inspired people to give of their time and energy. Thus, the gallery was an institution above and beyond the commercial realities that drove dealer galleries. Sutch wrote in 1954: ‘[W]e are not a commercial gallery; if we were we would have to charge much more … . but fundamentally we are a group of people voluntarily bounded together, giving up our time to promote ideas of better art and design in New Zealand; for example, the girl typing this letter is doing it for nothing in her and my lunch hour.’38

Kate Coolahan curated the 1960 exhibition Maori Art. PHOTOGRAPH BY MAX COOLAHAN, KATE COOLAHAN COLLECTION.

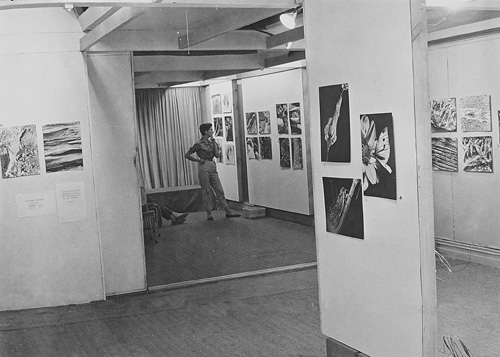

Max Coolahan’s 1961 exhibition, Images From Nature. PHOTOGRAPH BY MAX COOLAHAN, MUSEUM OF NEW ZEALAND TE PAPA TONGAREWA, F.6432/18.

When the gallery became an independent institution and altered its name to the Centre Gallery, it also changed its structure and the way in which it functioned. A public typist was invited to run her business out of the gallery, thus relaxing the need for volunteers to supervise the exhibitions on display during the week.39 And a succession of directors managed the gallery, including Mervyn Taylor, John Stackhouse, Elva Bett and Claire Jenning.

Yet these changes were not sufficient to prevent the Centre Gallery’s eventual demise in the late 1960s, after moving to 49a Willis Street, a space shared with the Montmartre Coffee Bar.40 When the Architectural Centre Gallery was first established in 1953 as a space in which ‘stimulating and experimental’ art could be shown, its permissive attitude was refreshing. But in the 1960s, the cultural context of Wellington was changing, and the Centre Gallery began to lose its ground as the only public institution in Wellington dedicated to showing modernist art and advocating modernist principles.

Significantly, both the National Art Gallery and the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts began to shed their conservative attitudes, and started to acknowledge contemporary developments in art. In 1967, for example, the National Art Gallery had an exhibition of Marcel Duchamp’s work;41 while in 1969 the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts Special Exhibition featured five artists – Melvin Day, Pat Hanly, Ralph Hotere, John Drawbridge and Don Peebles. Curated by Roy Cowan, it unashamedly celebrated the ‘international’ art practised by these artists.42

The emergence of dealer galleries such as the Peter McLeavey Gallery in 1968 again increased the opportunities for modernist artists to exhibit in Wellington, and further eroded the point of difference that made the Centre Gallery an important site of modernist art practice.43 The opening of the Bett-Duncan Gallery in 1968 may have had an even greater impact because of the role played by Elva Bett. Director of the Centre Gallery before starting her own gallery with Katherine Duncan, Bett’s decision to leave no doubt reinforced the idea that there were other more commercially effective galleries where artists could show their work. The Bett-Duncan Gallery took on many of the artists who were associated with the Centre Gallery and, under a different structure, adhered to many of its ideals – for example, undertaking to promote young artists, including a studio for art education, and publishing a newsletter about the gallery’s artists and exhibitions.44 In many ways, the Bett-Duncan Gallery can be thought of as a transformed Centre Gallery, with a new structure more suitable to the climate of the late 1960s (although this is not to suggest that it was an official transformation in any sense).

Unable to count on a guaranteed audience of artists and spectators interested in modernist experimentation, the Centre Gallery was left facing the conclusion, as Avis Higgs put it, ‘that the original idea [behind its establishment] had been accomplished’.45 It remains a testament to the efficacy of the impulse behind the original Architectural Centre Gallery that it remained so vital to the Wellington art scene for such a long period.

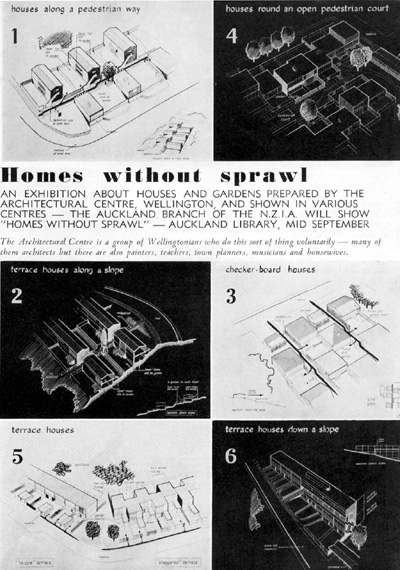

Home and Building grouped together six of the panels from 1957’s Homes Without Sprawl exhibition. COURTESY OF HOME NEW ZEALAND.

Te Aro Replanned had demonstrated the level of attention that could be generated through the Architectural Centre’s own exhibitions. Consequently, the Centre soon used its newly opened gallery for exhibitions that addressed both architectural and urban issues. These exhibitions involved the production of photographs, drawings, models, posters and publications to critique a variety of perceived urban problems and promote the Centre’s solutions to them.1 Suburban sprawl was an ongoing focus of attention, soon joined by increasing concern about the congestion of inner-city streets by the mushrooming number of cars and a corresponding shortage of car-parking. The architecture exhibitions were intended to serve a propaganda or advocacy function and, to maximise exposure, entry to them was free.2

The first was Living in Cities, held in March 1954.3 It promoted high-density, inner-city living as an alternative to the detached house and garden and, consequently, as an alternative to suburban sprawl. It gave particular attention to housing for people other than families with children – ‘the Forgotten People’ – the 40 per cent of households that comprised only one or two people such as ‘professional and clerical cadets’, spinsters and bachelors, childless couples, widows and widowers and so on: the types of households that did not need a three-bedroom house in the suburbs.4 The name by which the exhibition was known in its early stages – ‘Vertical Living’ – captures its intent better than that by which it was shown, but organisers feared that the working title might deter potential viewers by conveying the focus on high-density living: many people still had negative preconceptions about inner-city blocks of flats. Following its showing at the Architectural Centre Gallery, Living in Cities toured the country with the support of local branches of the NZIA and was therefore seen by a much larger audience than originally imagined.

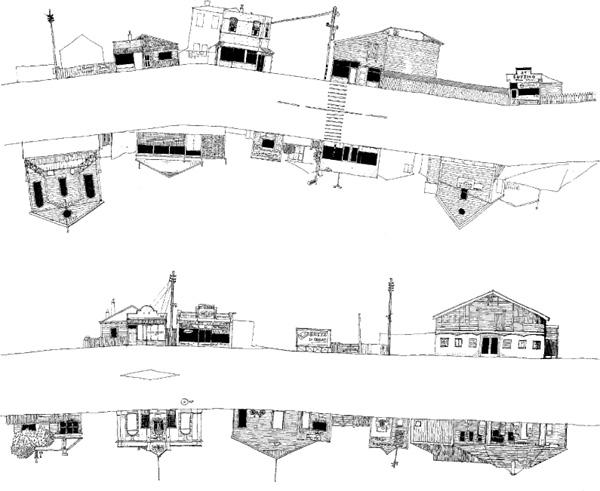

City Approaches of 1956. DRAWING BY DICK COCKCROFT.

Three years later, in February 1957, came Homes Without Sprawl: The Case for Higher Density Housing. It was a further indictment of suburban sprawl. Unlike Living in Cities, which advocated high-density housing, Homes Without Sprawl presented designs for low-rise, medium-density living, including terrace and ‘checker-board’ houses, for a site in Porirua.5 It was a major project led by Lewis Martin from late 1954. To keep urban issues in the public arena while the drawings for the show were being completed, another smaller exhibition, City Approaches, was held in September 1956. City Approaches examined the route into Wellington through Johnsonville and Ngauranga. It identified ‘derelict fences, power poles festooned with cross arms, lights, signs and wires against the sky, hoardings, squalid buildings, broken paving, and dumps of oil drums’,6 and presented a series of improvements. It did not attract as many people as Living in Cities had, perhaps because the Centre had not been as active in promoting this exhibition as it had its earlier ones. Certainly Homes Without Sprawl was much better publicised when it opened the following year, appearing in local newspapers, the Listener and Home and Building.7 ‘Can we afford to go on being so wasteful of our resources?’, it asked. ‘Obviously we cannot. But what can we do about it? … . there are other ways of building which actually make a 64% saving in land, as compared with today’s typical suburb.’8 Like Living in Cities, Homes Without Sprawl then toured the country with the support of NZIA branches – not just the main centres but also places like Rotorua, Oamaru and Invercargill. Other exhibitions followed: The Architectural Centre Looks at Oriental Bay (1964) and Wellington Hills Subdivided (1970).

At one level, these exhibitions offered alternatives to suburban sprawl. At another, they promoted town planning as the cure for urban ills. Allan Wild recalls that his generation used the term ‘town planning’ to mean ‘design, as opposed to accident, or habit; everything from lamp-post to urban design’.9 Whole new towns were being designed and built post-war, notably in England, and these seemed to epitomise synchronicity between town planning and architectural design. In Wellington, the issues took on increased urgency from 1958 because the Town and Country Planning Act of 1953 had required all local authorities to produce new district schemes within five years, but with the end of that five-year period approaching, there was no sign of a district scheme for Wellington.10

The Centre presented options for a higher density of housing in the 1964 exhibition The Architectural Centre Looks at Oriental Bay. DRAWINGS BY ALLAN WILD.

Thus, in 1958 when foundation member George Porter was elected president of the Architectural Centre,11 the first and main item on his new committee’s agenda was town planning: more specifically, how could the Centre get its ideas about town planning into the local newspapers? How could its members educate the Wellington public about the value of more and better town planning?12

Out of these questions, a campaign emerged; Centre members soon knew it as ‘the Project’. It encompassed initiatives to pressure the Wellington City Council into preparing a district scheme and establishing a town planning department (as distinct from a branch within the City Engineer’s Department). At the Centre’s AGM the following April, the architect Fred Newman proposed that the Centre should consider running an independent candidate in the November local body election, and a motion was passed that the Centre ‘investigate the possibility of an election ticket, and in addition approach the two parties [Labour and Wellington Ratepayers’ and Citizens’ Association] to ask them to include town planning on their programme’.13 Centre members collaborated with representatives of relevant professional bodies, residents’ associations and other organisations such as Save the Trams, and together instigated a press barrage to educate the general public, while also canvassing city councillors and council officers directly. This larger group, known as the Independent United Action Group (IUA), then identified a full ticket of fifteen candidates to stand in the November 1959 local body election. Porter was one of them. Threatened by additional competition ahead of the election, the Citizens’ Association offered to absorb the new ticket into its own and to make planning an election issue, in return for four of its seats.14 This the IUA accepted (albeit with two dissenting voices, James Beard and Helmut Einhorn),15 and thus Porter stood as a Ratepayers’ and Citizens’ Association candidate. The Citizens’ mayoral candidate, Ernest Toop, invited him to prepare the town planning plank of his election campaign.16 For the first time, town planning became an election issue. Porter made sure it received good press coverage, with the Evening Post, for example, quoting him thus: ‘Wellington is potentially one of the finest cities in the world … . But the work of town planning is being done by men in other professions. The benefits of planning knowledge and experience have so far been denied us.’17

Porter was elected and went on to serve five terms (fifteen years) as a city councillor. He made a particularly important contribution as chair of the council’s Housing Committee, a position he held from its formation in 1962 through to 1974.18 He believed that the provision of housing should be a major and ongoing function of local authorities, and made it so for Wellington city. Central government was building mostly low- and medium-density rental housing at this time, and Porter focused council resources on the provision of housing of a higher density. By 1970 the Wellington City Council had completed 1200 housing units and had another 1200 on the drawing board. Some of them, particularly the high-rise blocks in Nairn Street and Brooklyn Road, were not unlike those that had been proposed for the flanks of Te Aro Flat in the Te Aro Replanned project all those years earlier. Others heralded new enthusiasm for low-rise, medium-density alternatives.

In 1959, though, in his new role as a councillor, Porter was soon convinced that the council had its district scheme in hand. He had learnt that the City Engineer’s Department – or rather, a sub-branch of the City Engineer’s survey branch – had prepared a confidential draft district scheme for the inner-city area.19 The requirement to produce a district scheme came at a difficult time for Wellington. A multi-purpose council, it had ongoing responsibility for such things as public transport, electricity and water supply, milk delivery and abattoirs. In addition to these services, the construction of a new airport at Rongotai in the mid-to-late 1950s had soaked up considerable resources. The construction of a motorway into the city was about to do the same right through the 1960s and into the 1970s. Resources were stretched to the limit. Porter became concerned that the Centre’s activities were antagonising the council and hindering progress. He encouraged restraint from members,20 and concentrated on making good use of his own position on the inside by compiling a lengthy critique of the draft plan. His conclusion was that it contravened established town planning practice and was unduly complicated, difficult to understand and administer, and ineffective in many of its provisions.21 His comments resulted in a major rethink of the draft during 1960–61.22

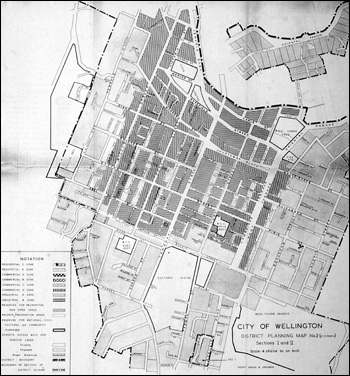

The council’s 1959 ‘district planning map’ for Te Aro Flat created zones for land uses such as residential, commercial, industrial and recreational. WELLINGTON CITY COUNCIL ARCHIVES, 00001:2275:68/1/1 PT 1.

There was, however, no stopping the Centre. When Porter took up his council position, he resigned his Centre presidency and was replaced by William Toomath. Aware that the Centre had succeeded in drawing public attention to urban issues in the past through exhibitions, Toomath determined that it was to this realm that the Centre would now return, and planned an exhibition that – for additional exposure – would coincide with the NZIA’s 1961 conference in Wellington.

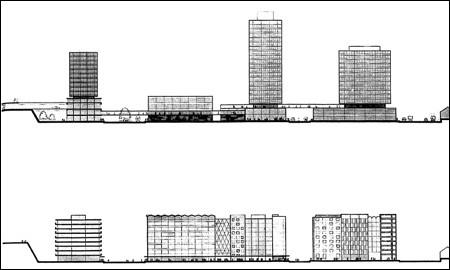

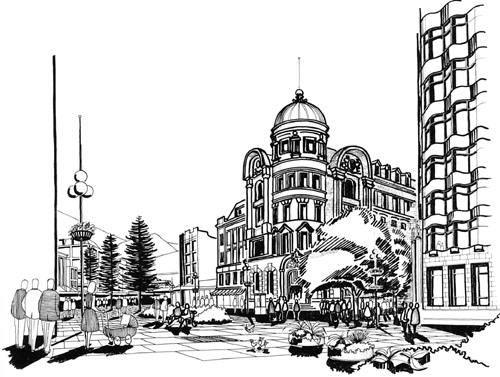

The evocatively titled Wgtn 196X was directed by English émigré architect and town planner Neville Burren.23 It aimed to identify problems that were apparent in the redevelopment of the CBD and to illustrate ways in which things might be done better. It identified a large number of small buildings occupying small sites; buildings with small squalid courts, unhealthy working conditions and low rental values; and disorganised traffic, pedestrian/vehicle conflict and parking chaos. Like Te Aro Replanned, it then presented a vision for Wellington, cleared of the existing buildings, replanned and built anew, with a focus on a quadrant to the east of Lambton Quay. The exhibition, and a related paper that Toomath, Burren and Al Gabites presented at the concurrent NZIA conference, encouraged the amalgamation of small sites to allow for comprehensive redevelopment, and proposed shopping streets closed to cars, covered pedestrian walkways at a range of levels and car-parking buildings connected to the covered walkway system. They also advocated the replacement of height restrictions with plot ratio bylaws to control bulk, and the use of podium-towers to ensure that each high-rise building retained adequate light and air.24 The recommendations were recorded in booklet form, copies of which were sold as the exhibition travelled to other cities.

Congestion on Lambton Quay, 1959. PHOTOGRAPH BY B. CLARK, NATIONAL PUBLICITY STUDIOS COLLECTION, NATIONAL ARCHIVES, HELD BY ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, F33143-1/2 (A59058).

Images from Wgtn 196X, showing the benefits of podium-towers (light, air, views) compared with high-rises which adjoin their neighbours. COURTESY OF THE ARCHITECTURAL CENTRE.

Questions regarding the proposed Wellington motorway further complicated the preparation of the district scheme in this period. By 1960, the National Roads Board had committed itself to building a motorway from Ngauranga into the city. The Roads Board and the Ministry of Works agreed that the only feasible route lay to the west of the city centre, cutting through the inner-city suburb of Thorndon and historic Bolton Street Cemetery, and then sweeping across Te Aro Flat.25 The National Roads Board agreed to contribute £20 million towards the cost of the motorway – a sweetener for the council – and by 1962 had started work on the outlying Kaiwharawhara section. The public remained unconvinced. Did Wellington actually need a motorway? Would it create more problems than it solved by bringing a greater number of cars into the city and then spewing them out into already overcrowded streets?

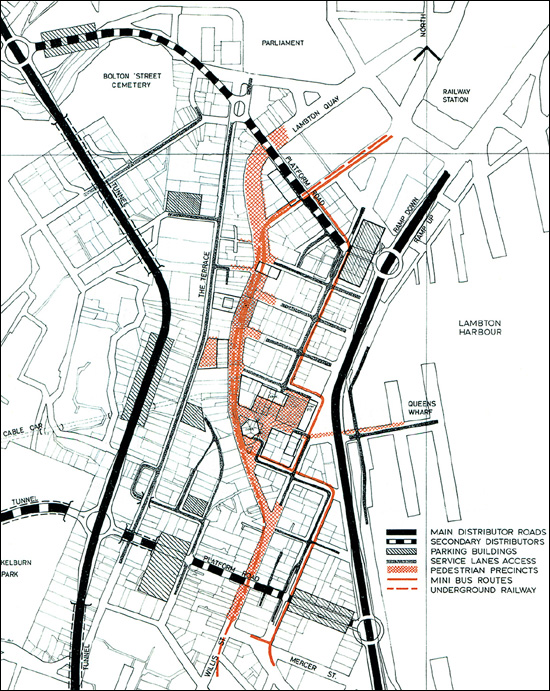

The council’s 1959 draft district scheme had not made allowance for a motorway. The City Engineer, F. B. C. Jeffreys, realised that it would have to do so and decided that, other than the code of ordinances, its preparation would be put on hold while decisions regarding the motorway route were made. He travelled to the United States, Europe, Britain and Australia in 1960 to investigate motorways and off-street car-parking.26 On his return, he recommended that the council commission an engineering firm to prepare a master transportation plan for the city, covering the motorway and the associated on- and off-ramps, as well as traffic within the city centre. This it did, choosing an American firm, De Leuw Cather & Co., which had worked on motorways in Auckland and Sydney. De Leuw Cather provided the council with its final report and drawings in August 1963.27 Its plan was consistent with the earlier proposal in that it positioned the motorway along the foot of Wadestown Hill, cutting through Thorndon’s residential streets and the Bolton Street Cemetery and then continuing across the city. This route became known as the foothills alignment. To overcome traffic congestion and the shortage of parking within the city, De Leuw Cather proposed a one-way street system that included north-bound traffic on Willis Street and south-bound traffic on Cuba Street, and off-street parking for 4000 cars.

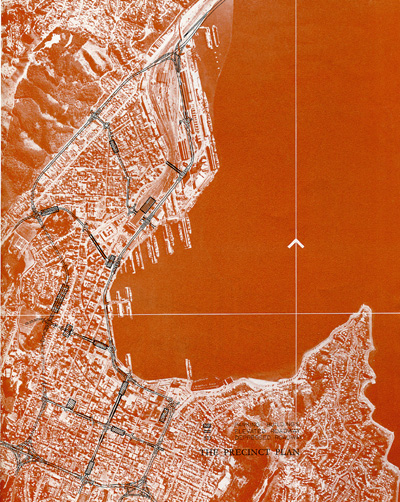

The whole of the De Leuw Cather plan attracted severe criticism.28 One of the critics, the Greater Wellington and Hutt Valley Retailers’ Association, commissioned Gabites & Beard (Centre members Al Gabites and James Beard) to prepare an alternative one-way street system, with greater attention to retailing.29 Beard, working with William Alington, not only formulated an alternative one-way street system to satisfy the retailers, but also spent evenings working pro bono on a much larger proposal, including an alternative motorway route to limit the loss of city amenities and a ‘Precinct Plan’ to enhance existing areas such as the government centre, the civic centre, the finance district and the university, particularly for pedestrians. Local newspapers showed that the public favoured the Gabites & Beard scheme – later published as a 48-page booklet – over and above the De Leuw Cather plan.30 The council eventually bowed to public pressure, asking De Leuw Cather to rework its scheme.31 The amended plan retained the Basin Reserve, removed traffic from Cuba and Manners Streets and included an extended Victoria Street to carry south-bound traffic. But the Ministry of Works had already started acquiring properties that lay on the foothills motorway path and there was no changing that part of the traffic plan.32

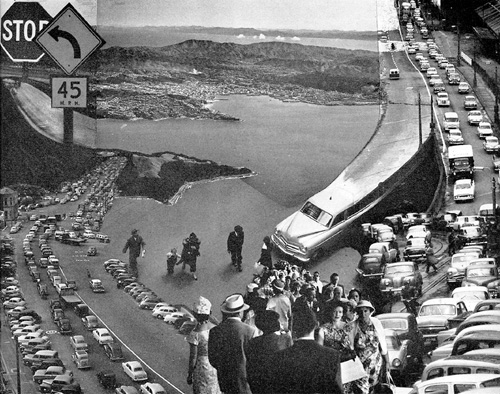

This 1965 collage emphasised the congestion of the city by both cars and pedestrians. COLLAGE BY GABITES & BEARD.

Paralleling the Centre’s ‘Project’ and Gabites & Beard’s ‘Precinct Plan’, the Wellington City Council made incremental progress with its district scheme and other town planning matters. It appointed an increasing number of town planners and planning consultants from 1962. In mid-1963, staff working on the district scheme turned to the council’s former critics – architects, town planners and interested others – for comments on the drafts of parts of the scheme. Another year rolled by and Porter became so frustrated with the slow progress that in mid-1964 he resigned from the council’s Town Planning Committee.33 ‘The architects, Cr Porter and the Architectural Centre would never be happy till an independent department for town planning was established’, the Dominion reported one of the other councillors as saying.34 Soon it was 1965 and another draft was circulated to interested parties for comment.35 After making their comments on this draft, Centre members seemed to accept that they had done all they could to influence the form the district scheme would take and that it was now up to the council to complete and publish it.

Gabites & Beard’s alternative motorway route and street system reduced the impact on Thorndon. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF LAND INFORMATION NEW ZEALAND, WITH ANNOTATIONS BY GABITES & BEARD.

The orange hatching shows the extent of the pedestrian precincts proposed by Gabites & Beard. DRAWING BY GABITES & BEARD.