12

VITALITY

Modern care of old people takes too little account of the fact that everyone ages at different rates, and chronological age is not always the best indicator. A much more important guideline for care is provided by the four periods that occur in everybody’s life — prevention, multi-morbidity, frailty, and dependency — which together form the new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’. If people are no longer allowed to be in control of their own lives, and individual responsibility is taken away from them, the consequences are disastrous for their vitality, wellbeing, and quality of life. This is why we are in dire need of a new approach to the care of old people.

On YouTube there is a video, entitled 100, in which people from Amsterdam look into the camera and say their age out loud. It paints a wonderful portrait of their lives. In less than a minute, the viewer sees a parade of babies, children, teenagers, adults, and old people flash by. The youngsters are gloriously exuberant. They are followed by a multitude of people — some timid, some confident, some smiling radiantly, some with a pensive look on their face.

What this little film shows us is the ancient evolutionary programme that is coded in our genes. The programme is still appropriate for our development from birth to adulthood. After that, however, it is no longer adequate because there is simply no programme yet for the much longer lives we lead today. In the YouTube portraits, the people in their fifties have a slightly more sombre look in their eyes than the rest. That is perhaps because they are confronted with a faltering body, which is something nobody exactly looks forward to at that stage of their lives. It will take many more generations before our bodies are adapted by natural selection to the modern environment and our much-extended lives.

The people in the clip aged 75 and over all beam into the camera as they proudly announce their age. Perhaps people finally dare to show their true selves once they reach old age. Perhaps it is that they are finally able to do so, and that it becomes acceptable, since social constraints become more relaxed in old age. When people can be themselves, they will differ increasingly from one another, and that is certainly true of older people. Each person has his or her own trajectory of development; each person has accumulated damage; and, with a certain amount of adaptation, that makes each person an individual character in old age, some bearing their years with more dignity than others. When buildings and appliances show the marks of time, we find it attractive. ‘You can see it’s been well used.’ Old people can impress us similarly with the way they cope with their lives. ‘If only I could live to that age!’ Then we don’t mind the odd blemish here and there.

It is not only the speed with which the ageing process progresses that can vary between different people — some people age much earlier than others — but the signs by which ageing manifests itself can also differ widely. One person might lose cognitive function, but still look fantastic; another may be frail but still possess a razor-sharp mind. And then there is the question of how they lead their lives, of course.

Given that people age so individually, it is remarkable that we have so many regulations that are based on chronological age, as if we were all the same at the age of 55, 65, or 75. And we always talk about old people’s care while tacitly assuming that we all mean the same thing by it. But the opposite is actually the case: there is no one way to care for old people. This is more than just quibbling about words. How are we to organise our society properly if we cannot even come up with a single, unambiguous definition of old people’s care?

Although the onset of ageing and the course it takes can differ widely from person to person, some episodes in life that everyone goes through can be generally distinguished. The more sharply these can be defined, the better society will be able to accommodate our ever-longer lifespans. I divide the human ageing process into four periods: prevention, multi-morbidity, frailty, and dependency. Together, they make up the stages of a new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’ — a structured and chronological division of ‘the rise and fall’ of a person through life — but this time irrespective of chronological age, and highly adapted to the fortunate circumstances in which we now live. What has not changed is the underlying ageing mechanism that leads to illness, impairment, and disability, and finally to death.

In part, these new stages are the same as what the medical profession considers health, but the definition of them is determined to a large extent by the goal a person has in mind at a given moment, in keeping with the broad definition of health as used by old people themselves, and affords a prominent place to a sense of wellbeing. That feeling of wellbeing is, as described earlier, linked to the quality of a person’s social relations and the environment he or she lives in. Medical problems do not play a large part in it.

THE NEW ‘AGES OF MAN AND WOMAN’

Prevention is the first stage in the new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’. It begins at, or even before, birth, and is by far the longest stage. Much is now known about the risk factors that accelerate the ageing process and about the factors that protect us and slow the process down. These are the ingredients for staying healthy, and, first and foremost, they are the responsibility of each individual: sitting a lot, eating a lot, and smoking, versus running, doing sport, and drinking in moderation. Despite all the information available, many people are still not sufficiently aware of the effect that good and bad habits have on them. And I am also referring here to the positive effects they can have on mood. Regular exercise creates a sense of wellbeing. Excessive alcohol consumption has the opposite effect.

In a world of plenty, many people are unable to keep themselves healthy into old age. They are targeted by people who want to influence their behaviour for their own profit. Young people are made dependent on alcohol, cigarettes, and fast food. Once they are hooked, such behaviour is difficult to reverse. This is precisely the aim of advertising that targets young people. It is an example of the way that the economic interests of a few take precedence over the many, and clash with a higher public interest: people staying healthy for longer. This is no different today than it was in the past. We now consider it a disgrace that children were forced to work for others’ gain at the start of the Industrial Revolution. We must consider whether the situation today is any different. This conflict between citizens and business should give us sufficient reason to prioritise prevention in the public domain. To claim, as some do, that prevention is each individual’s own responsibility is a blatant denial of the facts.

We are familiar with mother-and-child clinics from the start of our lives — from vaccination programmes, for example. At this stage in our development, everything is taken care of. This prevention in early childhood is a necessary start, but it does not go far enough. Staying alive in childhood is no longer the problem today. Looking after our bodies and minds as they develop to adulthood and beyond — that is the challenge of the modern age. Child obesity shows unequivocally that kids are eating the wrong things and taking too little exercise. This is an enormous public challenge. If the stairs in a building are difficult to find, of course you are going to take the lift. If fresh vegetables are more expensive than fast food, of course that will attract those trying to feed a family on a tight budget.

The public agenda for our children’s education is even more out of step. If we continue to insist on the rapid acquisition of specialist knowledge, we will be producing half-finished goods, from a social point of view. Nowadays, it is no longer sufficient to train children for a once-in-a-lifetime profession. We need to provide them with more skills than that. The most important thing is to make sure they realise that they are likely to live to be 100, and that they must take responsibility for organising their own life trajectory accordingly. We need a new attitude — ‘Old is not lame, old is cool’ — which they will also apply to their own later lives. We must prepare children for a lifetime of learning so that they can continue to participate in society on both a formal and informal level. This means that we must pay more attention to the acquisition of social skills. These are mainly learned in childhood, and must be sufficient to last a long lifetime.

There is no real agenda for preventive measures in old age, and so this needs to be developed from scratch. There are no, or almost no, official initiatives to promote good health among older people. Yes, people over 60 get a flu shot, but why are there no effective screening and intervention programmes for high blood pressure? Roughly half the cases of high blood pressure go undetected. And only half of those who are found to have high blood pressure receive treatment to normalise it. This result is nothing to be proud of. Doctors can now normalise anyone’s blood pressure with medication. The fact that this does not happen is all the more distressing, since we now know that high blood pressure in middle age not only affects the blood vessels in the heart and kidneys, but also more than doubles the risk of developing dementia.

The obesity epidemic and sedentary lifestyles require serious action. Many older people think that, now they are of an advanced age, they have earned some rest. A sedentary lifestyle is tempting, but is very detrimental in the long run. Everyone loves food and comfort; that is an essential part of our evolutionary fitness programme. But in today’s world of overabundance, we struggle with obesity, and it is clear that we must avoid such excesses.

It is not difficult to analyse the reasons for this undesirable situation. No one feels morally responsible for providing the necessary prevention agenda. This is compounded by the fact that many people earn a pretty penny from our unhealthy behaviour and the medical complications it leads to. A lot of health benefits are lost in this way, especially among the more economically disadvantaged sections of society. This lack of moral responsibility means we are still miles away from a situation where preventive measures help to promote health in a broad sense: not just the prevention of medical health problems, but also social problems.

One example can illustrate how important this is: older people with a small network of social contacts have a higher risk of mortality than smokers, even though smoking is seen as one of the greatest risk factors for illness and death. A healthy lifestyle includes investing in family, friends, and social contacts so as not to have to cope alone in old age. This is not only because not to do so jeopardises longevity, but also simply because it is not pleasant to grow old in isolation.

People will not be likely to take these preventive measures themselves, because there is no code for old-age care in our genes, and citizens are not sufficiently informed about such measures. Existing healthcare providers have no direct interest in introducing them, and simply ignore the looming challenge. Prevention must be shaped primarily by a sense of public responsibility. If we can translate our extra years of healthy life into paid or unpaid social participation, the putative problems of the ageing population will never arise.

The second stage of the new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’ is that of physical and mental complaints — due to tardy prevention. They eventually result in a visit to the doctor. He taps and listens, takes photos, and makes a diagnosis. On average, doctors are able to identify two or more chronic conditions in 65 per cent of 65-year-olds, and multi-morbidity — a fancy word for the co-occurrence of two or more chronic medical conditions in one person — is diagnosed in 85 per cent of 85-year-olds. These are almost exclusively complaints that develop as a result of the ageing process and are (as yet) irreversible. Unlike accidents, where the victim goes through a cycle of injury-surgery-rehabilitation-complete recovery, chronic conditions have no end. Lung function in people with emphysema deteriorates steadily; heart function diminishes gradually as a result of coronary atherosclerosis; and osteoporosis makes bones ever thinner. Once a chronic condition has set in, it is important to intervene quickly to keep any physical and cognitive complications at bay for as long as possible.

Our modern healthcare system is designed to deal with accidents and sudden illness in people who were more or less healthy before. It aims to address one problem as efficiently as possible, and then to discharge the patient from care. Specialist medicine is well able to treat single illnesses, greatly improving the prognosis for the patient. We have already seen the success of medical care in treating cardiovascular disease. Stomach ulcers are now almost a thing of the past, since the bacteria in the stomach wall that cause them can now be tackled with antibiotics. The prognosis for patients with Hodgkin’s disease has improved drastically, thanks to a clever combination of radiation and chemotherapy. Modern inhalation therapy has turned asthma into a mild condition, in most cases. And the list of examples goes on. This is a real triumph of modern medical practice. But it is disenchanting to see that older patients with several concurrent conditions do not receive adequate treatment or support. Medicine and society respond to their needs inadequately, or not at all.

The problems are many and varied. Old people with a wide range of complaints are systematically ignored by scientific researchers. There is no good reason for this, other than the focus on young(er) people, which is taken for granted. This is a case of ageism — discrimination of people on the basis of age alone. The result is that we do not have sufficient scientific knowledge to provide the best care possible for most of the patients who present themselves to general practitioners and hospitals. Instead, specialist medicine leads to a jumble of different, uncoordinated actions. Most older people have to go through life with a list of appointments like a debutante’s dance card, and a huge box of pills. Much more often than we would like, these treatment strategies and medications influence each other negatively. In such cases, less specialist medical care would lead to more health benefits. The need to coordinate and integrate different strands of patient care is increasing all the time, and this has led to a boom in the number of medical managers and care coordinators. However, since they are deployed separately for each specialist problem, some policymakers are now considering trying to turn the tide by coordinating the various coordinators and managers …

More tools from the same box will not help with the complex problems of older people living with several (chronic) conditions. The crux of the matter is that the medical system of today is designed to cope with the health problems of the past. A new approach is necessary to enable us to treat today’s complex patients properly. For the most part, the current divisions in medicine along the lines of individual organs and diseases must be broken down. General medical knowledge must be prioritised once more. The complex problems caused by different, concurrent conditions have become standard among old patients.

Who should feel called upon to tackle the problem of creating a new agenda for multi-morbidity? Everyone, in fact. Doctors, nurses, and paramedics will need to rethink the subject matter of their professions. Hospital managers will need to change the way departments and outpatient clinics are organised. Health insurers and policymakers must realise that a remuneration system based on specialist interventions is a hindrance to the development of a more generalist approach to the complex health problems of older people. The current system burdens patients with too many pre-treatment, treatment, and post-treatment trajectories, generating too many diagnostic assessments and extra treatments, as well as high costs to society. Governments must shift the current (financial) incentives towards helping to promote a change in care. Presently, the initiative lies far too much with the care providers, who still have too little interest in rethinking their offer. Older people must help force the necessary change, since the system will not change of its own accord. They feel sorely the lack of a general approach, they have moral rectitude on their side, and they will be the first to profit from such improvements.

The next stage in the new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’ occurs when several interacting disease processes render an old person ‘frail’. This is the phase in life when minor setbacks can quickly snowball into a full-blown disaster. It is therefore important to identify frailty in older patients early, and then to implement medical and technical measures only with extreme caution. Prevention aims to stop disease developing, and, if it does occur, to use an appropriate method of treatment to avert any lasting complications, or to delay them for as long as possible. However, with frail old people, the primary aim is to preserve their ability to function in daily life.

A woman of 85 with an extensive medical history is diagnosed with cancer. The specialist proposes surgery and chemotherapy. A full recovery is no longer possible, but the treatment can slow the progress of the disease, so the patient agrees to it. Complications arise, and the woman spends the final months of her life in a hospital bed. The question is whether that is really what she wanted.

Doctors far too rarely offer the option of foregoing treatment. Far too often, they persist with a plan aimed at bringing about recovery, although they know that will never be the result. It is the responsibility of specialists to make it clear to patients when the expected effect of a medical intervention is minimal. Medics need to be far more aware that their primary role when treating frail old people is one of support. Many specialists believe they have no more part to play when a specific (medical) treatment is found to be impossible, or is rejected. But rehabilitation, adaptation, and support can enable a patient to live well with limitations and impairment, so that they can continue functioning well in their familiar environment for longer.

For frail old people in particular, medical action should be aimed at optimising their health in the broadest sense. This is easier when frail older people are allowed to set their own personal goals. This is where the general practitioner can play an important part, making explicit choices together with the patient. General practitioners can decide not to implement certain specialist interventions or treatments, and to sustain the wellbeing and functionality of the patient in other ways. General practitioners must become more like ‘personal physicians’ for their patients.

In Chapter 8, I illustrated how difficult it can be to identify frailty in patients. It will also therefore be difficult to prevent the unwanted side effects of medical interventions. But that does not relieve healthcare professionals of their obligation to pay this issue far more attention. Frail older people should not be treated as healthy adults who just happen to have grey hair, just as children should not be treated simply as miniature adults.

The fourth and final stage in the new ‘Ages of Man and Woman’ is dependency. This often concerns older people who have multiple debilitating conditions, or who have dementia. In this period of their lives, a wide network of informal carers and professional care workers becomes active. Older people can quickly lose control over their own lives in this stage. That is why it is so important that their family and friends are able to advocate for them. I call this a ‘vicarious advocate’. It is the responsibility of older people to organise such an advocate themselves while they are still in a position to do so. This ensures that there will be no doubt about who will speak for them when they can no longer speak for themselves. Quality of life is the guiding principle; prolonging life retreats into the background. The goal now is to increase the old person’s sense of wellbeing, rather than to postpone death.

Two-thirds of doctors in the Netherlands are of the opinion that people in the final stage of their life are often treated medically for longer than is desirable. Proposals to stop treatment go against everything doctors are taught during their training, when the entire focus is on saving lives. Doctors systematically overestimate a given treatment’s chances of success. This gives patients the idea that modern medicine has a solution to everything. In this way, doctors and patients hold each other in the grip of an illusion that preserving life is always feasible. Medicine should provide care to people always with a view to the value it brings for them. A change of attitude is required when treating dependent older people.

Fortunately, it is possible in the Netherlands to speak openly about death. When there is agreement between doctor and patient, futile medical treatment can be discontinued promptly. Sometimes this brings the point of death closer, since prolongation of life is no longer being pursued at all costs. Because non-treatment means they suffer no side effects from medical interventions, patients experience a greater sense of wellbeing. In this final phase of life, the doctor must take a back seat, remaining available if symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath, or anxiety surface, to relieve them with consultation, support, or medication.

In a period of dependency, there is no longer a relation between wellbeing and specific illness. This stage requires primarily bespoke, humane care. The amount of care required by a dependent older person is naturally determined by the person’s physical and mental capacities, by those closest to them, and by their immediate surroundings. Most people approaching the end of their life prefer to be at home, but admission to a care home is sometimes unavoidable. Such a move is often seen as a catastrophe by older people. The question is why. Obviously, they are afraid of the approaching end, but perhaps sometimes care homes fail to offer what older people would like. It sounds paradoxical, but in the phase of dependency, with the end of their lives in sight, people need more than ever to be in control of their own lives, or to know that those closest to them are in control.

Are the workers in the care home sufficiently able to listen to the residents and cater to their needs? I think professionals in long-term care think too often in terms of medical, technical, and legal issues, instead of making use of their own, hard-earned expertise. This leads them inadvertently to do things that are not to the benefit of (frail) older people.

OPTIMISM AND ZEST FOR LIFE

Within geriatric medicine, it is often said that we should not seek to add years onto life, but that we should add quality to years. That is a dubious statement. I believe everyone wants to live longer, provided that their quality of life remains good. However, people are primarily responsible for their own quality of life. Medicine can create the preconditions for this, by keeping people’s bodies and brains in good form for longer, but, when it comes to it, people must find their own sources of satisfaction. They must ask themselves what they are living for, and what their ambitions are. If they have a clear view of those goals, they can strive to achieve them, even in old age. The manifestations of the ageing process then become less important.

Thus, life in old age does not differ substantially from life when we are young or middle aged. Everyone has personal ambitions that they would like to fulfil, and everyone encounters stumbling blocks, hurdles, and setbacks in pursuit of them. The skill is to be able to overcome or circumnavigate those hindrances. Luckily, that is precisely what we have evolved to do. If we gave up at the first sign of adversity, we would never have made it so far as a species. Only the nature of our ambitions, and the nature of the setbacks we face, change as we get older. While it is mainly our social position and material wellbeing that are important to us when we are young, we begin to cherish our social relations more when we are old, despite illness and impairment. Fortunately, by then we have learned a lot from life. This explains why most older people rate their quality of life as good or very good.

A follow-up study on morbidity was made of people whose attitude to life was measured in middle age. When they developed an illness in old age, its progress was better among those who had a more optimistic outlook on life than did their peers in middle age. Following a heart attack, optimists were less likely to die, and more likely to recover more quickly and to achieve a better level of functioning after rehabilitation. It seems that having an optimistic attitude to life keeps you physically healthier. And the reverse also appears to be true — ‘a healthy body houses an optimistic mind’. In the families that took part in the Leiden Longevity Study, the offspring of parents who reached a higher age than average had a more positive outlook on life than their partners.

Social scientists stress that vitality is an attribute that is important for achieving happiness in old age. Vitality is the ability to develop to full capacity, to get the most out of life. This will to make something of oneself depends on motivation and introspection: what do I want, and where am I heading? It requires a positive attitude, and the energy to invest in that outlook. However, people also need the resilience to cope with setbacks. A (slightly too) positive view of your own abilities — optimism — is necessary to achieve your ambitions successfully. For some people, this seems like an impossible task. Vitality — call it zest for life — is an inborn trait, and it has its basis in our evolutionary fitness programme. It matures during childhood and adolescence, and is honed by the experiences people gather through life. Just as with other biological phenomena, it is also a combined result of nature and nurture — the influence of your parents and your environment.

Vitality is also the ability to appreciate what is possible and what is not, a balancing act between your own abilities and the ability to accept help from others. There is nothing more frustrating than pursuing goals that are unachievable. You have to be able to adapt your ambitions to the prevailing circumstances, and then you can achieve the goals you have set yourself. Old people are better at doing this, because they have so much experience to draw on.

Apathy is the opposite of vitality, and is defined by psychiatrists as a lack of motivation caused by a disturbance in mental functions. It is similar to depression, but is not the same thing. Depression is characterised by the fact that it causes people to suffer from feelings of sadness. With apathy, it is not so much melancholy that plays havoc with the mind, as the example below will show. A married couple, well into their seventies, came to my surgery, and the wife was the first to speak. ‘He used to have a busy job, but now he does nothing. He just sits on the couch, waiting. I’m worried there might be something seriously wrong with him.’ I asked her husband what he thought about his wife’s account. He looked at me, and answered hesitantly, ‘I haven’t got a problem. She thinks I’ve got a problem,’ and he pointed to his wife. The man himself did not appear to be suffering in any way. But those around him were worried, since sometimes people’s characters can change greatly.

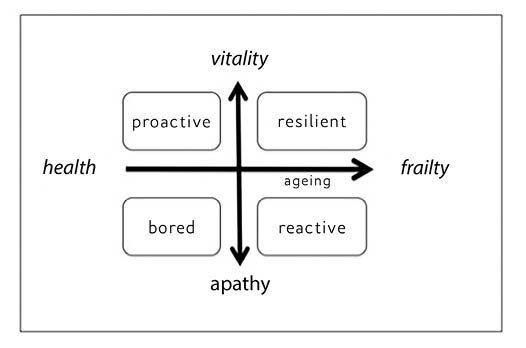

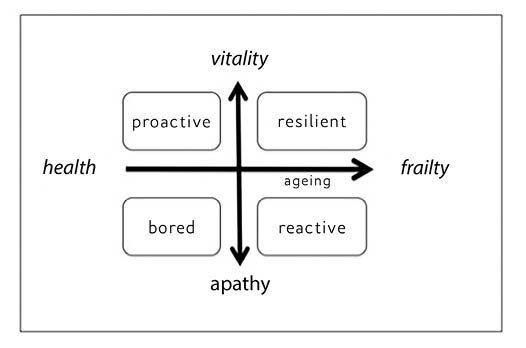

Some teenagers are apathetic, and spend much of their time doing nothing at all. Others are so full of zest for life that it’s tiring just watching them. This shows that vitality is not linked to age, and is also independent of gender, educational level, and socio-economic class. In any given group we find the extremes of vitality and apathy, and everything between. In the diagram on the opposite page, the biological process of ageing, progressing from left to right along the horizontal axis, is measured against a vital attitude to life, represented by the vertical axis. The biological process of ageing and vitality are largely independent of one another. This is not as obvious as it may seem. Often, people assume that the two axes are the same. People — doctors and researchers included — often mistakenly believe that slowing the ageing process and postponing the onset of illness and complications will directly benefit our sense of wellbeing. This is what we call medicalisation: viewing life exclusively from the standpoint of medicine and medical technology.

The horizontal axis representing the ageing process indicates the public responsibility of professionals to take the initiative for prevention and care. The vertical axis represents our own responsibility to strive for our goals in life. If older people consider social contacts to be of great importance, and want to exercise control over those contacts themselves, then we, as family and friends or as professionals, must play a supporting role. Quality of life, wellbeing, and happiness all result from vitality in life and an ability to take advantage of the possibilities available. The ageing process, health, illness, and impairment certainly have a part to play in this. They determine a person’s level of physical and mental functionality, and an ability to manage day-to-day activities is contingent on them. But even if functionality is reduced, people are generally able to adapt — except in the final year of life, when, on average, satisfaction with life falls.

Our current thinking about increasing life expectancy is still too biased towards preventing and recovering from sickness and impairment, rather than concentrating on the day-to-day functioning and wellbeing of (frail) older people. This leads to a situation where the goals pursued by those involved in caring for old people do not always correspond to the ideas of those old people themselves. Professionals should not just concern themselves with the question of how we can stay healthy longer, but also with that of how they can stimulate older people to use their vitality in dealing with the problems they are saddled with due to the ageing process. Too little attention is paid to encouraging and supporting older people in remaining socially active, despite their sickness or impairment. This is what enables older people to maintain a high level of wellbeing. Friends, family, informal carers, and professionals need to stimulate people to keep on having dreams, nurturing their ambitions, and achieving realistic goals, despite their age and their reduced physical and mental functionality.

One example from my own neighbourhood is that of the old man who lives two doors down — the two of us first met when he was 85. He started working as a shipyard steelworker at an early age. He can talk animatedly about the time he worked for the union and took to the barricades to fight for a better deal for the workers. He was in his late fifties when he was sent into early retirement. He and his wife soon realised that they had to do something to give their life as a retired couple content and colour. He started taking lessons from a well-known local artist who was inspired by Zen Buddhism. My neighbour learned to paint; and when his hands became too unsteady for him to be able to continue painting, he took up an alternative art form. This led to the creation of a whole series of haiku poems. Some of his work was presented to the public in a small exhibition on his 89th birthday.

This new thinking about vitality and ageing requires a revolution in thought like that which took place in cultural anthropology. Until the fifties and sixties, anthropologists attempted to understand and explain people’s behaviour from the point of view of their own norms and values. This is called the ‘etic’ approach. The view of the WHO on health is a good example of such an approach: a committee determines for other people what health is. This approach was abandoned by anthropologists, who began studying behaviour from the point of view of the people themselves. In this, the ‘emic’ approach, researchers throw off their own frame of reference, and adopt that of the people they are studying. This explanatory model, therefore, takes as its starting point the socio-cultural environment of the people who live in it, and the personal norms and values of the individual.

If we apply the emic approach to the care of older people, a meeting between a (professional) carer and the older person in question will begin with a dialogue between equals. The older person must be able to express his or her wishes and expectations. Professionals must be able to empathise with older people to understand their experience of the world and the problems they face. Only when that is clear can the caregiver be of service to the older person: ‘What can I do to help you?’ Naturally, this dialogue must be continued when medical treatment is under consideration. It is essential that such treatment is not only effective, but also feasible and acceptable to the patient. This entails the patient and doctor coming together to decide, which can lead to decisions being made that are in conflict with modern medical opinions, standards, or conventions. Research into this joint decision-making process shows that doctors and patients acting together often opt for a less-invasive treatment than that recommended in the guidelines. Not all older people’s problems require medical treatment, but sometimes the doctor and patient may also decide to do more than usual.

Professional and informal caregivers need to take a new approach. Much more than now, older people’s voices must be heard when it comes to the necessary restructuring of the modern healthcare system. The obvious starting point is the home, after which come family and friends, neighbours and, if necessary, the doctor and hospital. Currently, the process is completely the other way around. Enabling an older person to stay closer to home, in his or her immediate neighbourhood, we must do what we can to prevent a situation where all help for older people becomes medicalised. Many problems faced by older people require non-medical solutions, although illness and impairment will always be in the background. Those problems often have to do with feelings of wellbeing, and medicine cannot always provide an answer to such problems.

In public and professional debate, the question regularly arises of whether it is morally acceptable to demand of (frail) older people that they remain full of vitality; that they should set their own goals and achieve them themselves. If someone wants to sit apathetically on the couch all day, why shouldn’t they be allowed to do that? On the other hand, we have to ask ourselves whether today’s social order affords older people sufficient opportunity to maintain their vitality. Do older people have a worthy position in our society? Are they supported and valued enough? Guaranteeing mental and social vitality is a shared responsibility that requires good interaction. Everyone must come to realise how important it is to work on maintaining vitality in life. Older people should embrace the concept, because it is directly connected to their desire to take control of their own lives and to remain independent.

GREY IS NOT BLACK AND WHITE

The research report Many Shades of Grey: ambitions of 55+ was published in 2013 to chart older people’s own aspirations. The title is a reference to the fact that we see extremely positive or extremely negative images of ageing in the media, but never the ‘grey’ middle ground, which is where most older people find themselves. The research presents a cross-section of Dutch 55-to-85-year-olds. The report shows an optimistic future predicted for and by older people. They want to retain control over their lives, whether in the area of housing, working, care, or social contacts. Almost all want to be at the helm of their own lives, but when it comes down to it, they often feel powerless because existing public and private organisations will not allow it.

Increasing numbers of older people work actively and productively in the paid or voluntary sector. Social participation, even if it is unpaid, plays a large part in providing a sense of purpose to life, and in maintaining social contacts. But working in old age is not an obvious thing to do for many people. A large majority of over-55s who are still working take a predominantly positive view of the fact that they will soon be able to retire. However, there are also many who want to continue working, if it is possible under their own terms — for example, by going part-time or doing a different type of work. They are also willing to take a salary cut of up to 25 per cent. A quarter of those older people who no longer work say they would return if it were on their own terms. That proportion decreases, of course, with increasing age. Older people have a large sense of their own responsibility when it comes to their finances. Almost half those questioned felt in need of advice on how to deal with a possible drastic drop in their income, in order to pre-empt any problems that might entail.

As people get older, more of their relatives, friends, and acquaintances die. Despite this, the survey shows that older people are generally satisfied with their existing social contacts. The need for such contacts does not increase with age. Many older people argue that new social contacts must arise spontaneously and cannot be forced, especially in old age. The report shows the inherent strength of old people. The overwhelming majority have already thought about these issues, and say they feel able to cope alone with the loss of a partner or a loved one.

Almost all older people would like to take more responsibility for their own health. This is an argument for more appropriate care, and it would probably produce better results. But most older people do not really know how they can assume this responsibility for themselves. When the researchers made the idea more tangible by confronting the interviewees with a hypothetical health problem, the vast majority showed they were ready to take the initiative. They were keen to seek out information actively, and were prepared to adapt their lifestyle to the demands of the health problem. This also included them taking the necessary measurements — such as their blood pressure — themselves. Remarkably, they also displayed a desire to regulate their own use of medicines, as diabetic patients do with their insulin. The respondents’ feeling of ‘entitlement’ to care increased with increasing age. Over the age of 75, the majority of Dutch people remain stuck in the old patterns they learned while growing up.

This survey shows that the majority of 55-to-85-year-olds are happy in their home, and would like to remain living there as long as possible. They have a wide variety of specific wishes for the future. In this regard, older people must take the initiative so that they are not forced to move at short notice as a result of increasing physical or financial problems. Only half of the older people questioned had thought about this.

Old people are caught in a dilemma, between ‘Do I have to fend for myself?’ and ‘Am I able to fend for myself?’ Older people need to start taking a different attitude to life, based on finding a balance between taking responsibility for themselves and making use of what public services can offer them.