Sequoia & Kings Canyon - Introduction

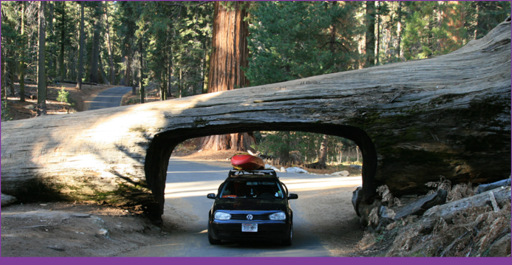

A motorist drives through Tunnel Log (8-feet high, 17-feet wide)

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks reside in a contiguous region of the southern Sierra Nevada. Each park has its own boundary and entrance, but they share the same backbone, the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Since 1943 the parks have been administered jointly by the National Park Service. John Muir, one of the first American naturalists, was an early advocate of preserving and protecting regions of exceptional natural beauty. While wandering the High Sierra he formed a kinship with the trees, the rocks, and the mountains, and few areas were more important to Muir than the groves of giant sequoia and mountains of the High Sierra (including Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the lower 48 states). He spent much of his life writing, speaking, and petitioning on their behalf.

“Most of the Sierra trees die of disease, fungi, etc., but nothing hurts the Big Tree. Barring accidents, it seems to be immortal.” – John Muir

Muir was just about right. The wood and bark of the park’s namesake is infused with chemicals that provide resistance to insects and fungi. Its bark—soft, fibrous, and in excess of two feet thick—is a poor conductor of heat, making the giant sequoia highly resistant to fire damage. They rarely die of old age, either. Many sequoias are more than 2,000 years old. Ironically, extreme size is its greatest threat. Most die by toppling over under their immensity. Relative to their massive size and height, the roots are shallow and without a taproot. Wet soil, strong winds, and shallow roots are a recipe for a toppled sequoia.

“God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand tempests and floods. But he cannot save them from fools.” – John Muir

Fools found their way to the sequoia groves of the Sierra Nevada and did what they could to topple these mighty trees. In 1888, Walter Fry sought work as a logger (even though sequoias were a relatively poor wood that splintered easily). Somewhere between felling a sequoia (which took a five-man team five days to complete) and counting its 3,266 rings, he had a change of heart. At the same time conservationists were collecting signatures to protect the forest; the third signature was none other than Walter Fry, who decided to put down his axe and channel his efforts toward protecting the trees from the men he had worked alongside. Protection was achieved in 1890 thanks to establishment of a national park. Fry was hired as a road foreman in 1901 and four years later he became a park ranger. Over the next three decades he became the first civilian superintendent (originally the park fell under army supervision) and the first nature guide, who continued to lead guests on guided walks until his retirement in 1930 at the age of 71.

“When I entered this sublime wilderness the day was nearly done, the trees with rosy, glowing countenances seemed to be hushed and thoughtful, as if waiting in conscious religious dependence on the sun, and one naturally walked softly awestricken among them.” – John Muir

John Muir didn’t have to cut down a sequoia tree to understand its significance. The privilege of being able to walk among them was enough. Muir’s communion wasn’t just with the trees, it was with nature itself. He led energetic hikes into the High Sierra and forged a trail along the steep east face of Mount Whitney. Today, the 211-mile trail from Yosemite National Park to Mount Whitney bears his name. He dreamed of an expanded park, reaching far into King’s Canyon, but it wasn’t until 1940 that Kings Canyon National Park was established. Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, wanted to make a park that was impenetrable to automobiles. Kings Canyon was ideal. Today, a single road leads into the canyon and terminates abruptly at Roads End. No road within either park crosses the Sierra Nevada. Mount Whitney, the tallest point in the lower 48, cannot be seen from any roadway. The park is left mostly undeveloped, allowing visitors to walk softly awestricken among its natural beauty, much like John Muir did when he first came to the Sierra Nevada.