Half Dome at sunset © Shutterstock

“I have seen persons of emotional temperament stand with tearful eyes, spellbound and dumb with awe, as they got their first view of the Valley from Inspiration Point, overwhelmed in the sudden presence of the unspeakable, stupendous grandeur.” – Galen Clark

Times have changed, but the scenery remains the same. The first sight of the valley still possesses the power to leave guests weak in the knees and with a tear in their eye. These very sites were the catalyst fueling the conservation movement. The smooth granite peaks inspired a man, by his own admission an “unknown nobody,” to become one of America’s great naturalist writers, thinkers, speakers, and the unofficial “father of the National Parks.” Giant sequoias encouraged one of the country’s greatest presidents to protect similar exhaustible resources and landscapes. Beautiful vistas motivated a photographer to capture their essence, their “unspeakable, stupendous grandeur,” allowing the world to experience the spellbinding awe felt when a visitor first views the valley from Inspiration Point or Tunnel View.

The first non-Native visitors to this majestic valley didn’t come for respite or rejuvenation. In 1851, the Mariposa Battalion was called to the Sierra Nevada to settle a skirmish between Native Americans and local ’49ers hoping to dispossess their land. These soldiers found the Natives, whom they believed to be the Yosemite Tribe, in a valley about one mile wide and eight miles long. Upon arrival, the battalion didn’t stop to stare in bewilderment or give thanks to a greater power capable of creating such a spectacle, instead they prepared to burn it down, thus starving the Natives. Eventually the feud was settled and it was learned that the natives were known as Ahwahneechee; Yosemite was actually their name for the Mariposa Battalion.

“If no man ever feels his utter insignificance at any time, it is when looking upon such a scene of appalling grandeur.” – James Mason Hutchings

James Mason Hutchings and Galen Clark shared similar sentiments when it came to Yosemite Valley. In 1855, Hutchings was led into the valley by Natives. He quickly became enamored with the scenery and wasted no time moving in. In his opinion, the region had “value” as a tourist attraction, so he immediately began promoting it as such. From 1855 – 1864, the valley was visited by just 653 tourists. Insufficient infrastructure resulted in trips from San Francisco to Yosemite Valley that took 4 – 5 days (on foot, horseback, and carriage).

Galen Clark’s wife died young, so he too moved to California seeking his fortune. In 1853, Clark contracted a severe lung infection. Doctors gave him six months to live. “I went to the mountains to take my chances of dying or growing better, which I thought were about even (Galen Clark, 1856).” Shortly after his arrival he discovered Mariposa Grove, and from that point on much of his time was spent writing friends and Congress requesting passage of legislation to protect the area. He gained the support of John Conness, a Senator from California. In 1864, in the midst of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill preserving Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove under state control. Clark happily became guardian of the Yosemite Grant, including the grove of trees that inspired him. As guardian he was expected to protect the park from overeager tourists, maintain roads and bridges, and deal with residents and businesses residing here. All this needed to be done on a meager $500 annual budget.

One business in the valley was Hutchings House Hotel. James Mason Hutchings became Galen Clark’s biggest pest. He refused to abide by the $1/year government lease. Essentially squatting on public land, he expanded his operations and built a sawmill.

Hutchings hired a wandering shepherd by the name of John Muir to run his sawmill. Born in Scotland, raised in Wisconsin, Muir skedaddled to Canada to avoid the Civil War and returned to work as an industrial engineer in Indiana. The sharp mind that had allowed memorization of the Bible’s New Testament and most of the Old Testament by age 11 was on display in an industrial environment. His inventiveness and intellect helped improve many machines and processes, making life easier for the laborers at a plant manufacturing carriage parts. When a work accident nearly left him blind, Muir chose to be true to himself. He had always wanted to study plants and explore the wilderness. He set out on a 1,000 mile walk from Indiana to Florida, where he planned to board a ship to South America. Unfortunately, he contracted malaria before he could set sail across the Caribbean. While recuperating in Florida, he read about Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada. Nursed back to health, Muir booked passage to California instead. He arrived in 1868. After a brief stint as a shepherd, Muir moved into Yosemite Valley to run Hutchings’ sawmill, where he built a cabin near the base of Yosemite Falls for $3, what he considered to be “the handsomest building in the valley.”

As Muir was settling into his new life, Hutchings was being evicted. In 1875 Galen Clark allowed him to store his furniture in a vacant building. Hutchings moved in more than his furniture, he set up his entire operation: Wells Fargo Office, telegraph, post office, everything. Once again, he was running a hotel. This was the final straw. Hutchings, banished from Yosemite, moved to San Francisco where he started a tourist agency and wrote two best-selling books including In the Heart of the Sierras.

Meanwhile, Muir had become a bit of a Yosemite celebrity. All of the park’s guests wanted exposure to his brand of enthusiasm and passion for the ecology and geology of the High Sierra. In 1871, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the author whose work Muir had read many a night from the light of a campfire, arrived at Yosemite. After just one day in Muir’s company, Emerson offered Muir a teaching position at Harvard. Even though he had spent much of the past three years unemployed, Muir declined the offer to remain in what he called “the grandest of all the special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter…the sanctum sanctorum of the Sierra.”

By 1889, Yosemite Valley was officially a tourist trap. A cliff-side hotel was constructed at Glacier Point. Raging fires were hurled over the cliff’s edge to create a waterfall of fire. Tunnels were carved into trees. Muir had seen too much, so he set out to make Yosemite a national park. Witnessing how the establishment of Yellowstone National Park increased passenger traffic for Northern Pacific Railroad, the Southern Pacific placed their support behind the endeavor. In 1890, Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite became National Parks.

James Mason Hutchings, now 82, wanted to make one last trip into Yosemite Valley. His wish was granted, but a tragic horse carriage accident resulted in Hutching’s death. In what can be seen as a peculiar twist of fate in a seemingly tragic accident, the funeral service was held in the Big Tree Room, formally known as Hutchings House: the old hotel he was evicted from and the one place he loved more than any other.

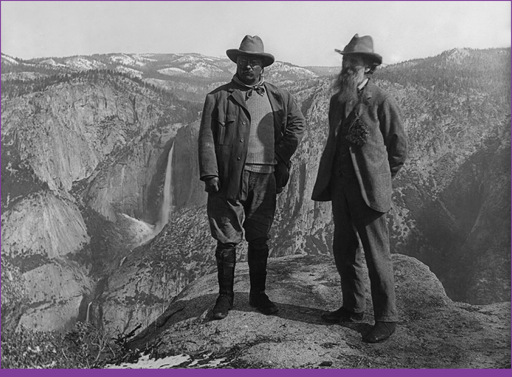

Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir at Glacier Point

In 1903, John Muir and President Theodore Roosevelt camped beneath the stars at Glacier Point. President Roosevelt stated “it was like lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by the hands of man.” It wouldn’t be long until the hands of man wanted to dramatically change Yosemite. San Francisco required water to support its ballooning population. Dam proposals were focused on a tract of land within park boundaries known as Hetch Hetchy Valley. Muir found Hetch Hetchy even more appealing than the more popular Yosemite Valley. He passionately opposed the dam proposal and for years legislation was held up in a political quagmire. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson finally signed a bill approving the dam. One year later, an exhausted Muir died at the age of 76. John Muir arrived in Yosemite, “the sanctum sanctorum of the Sierra,” as an unknown nobody. He left as president and founder of the Sierra Club, renowned writer and naturalist, and catalyst in the creation of Yosemite, Sequoia, Mount Rainier, and Grand Canyon National Parks. He is the father of the National Parks.

In 1916, a shy 14-year old boy, sick and in bed, decided to read James Mason Hutchings’ In the Heart of the Sierras. Intrigued, he convinced his parents to vacation at Yosemite. What he saw left an indelible mark. Years later, the young man worked as caretaker at the Sierra Club’s LeConte Memorial Lodge in Yosemite Valley where he spent time as a photographer for Sierra Club outings and classical pianist for lodge guests, wowing visitors with striking imagery and wistful music. This man is Ansel Adams, one of the greatest landscape photographers of the American West, in particular Yosemite. A visit to Yosemite can become a life-changing experience. Its unspeakable grandeur is so overwhelming you may find yourself inspired like James Mason Hutchings, Galen Clark, John Muir, President Roosevelt, and Ansel Adams were before you.