TWO

Small Actions, Big Themes

‘Small minds are concerned with the extraordinary, great minds with the ordinary.’

BLAISE PASCAL

It might seem that massive repression can be defeated only by equally massive resistance. But small actions can also embody aspirations for larger freedoms.

Such actions are often about choice. Women decide whether they will choose to wear (or not wear) a headscarf. Protesters insist that they, not the government, should decide if they will exercise the basic right to sit behind the wheel of a car. Mischievous Facebook posts can be used to reassert basic rights.

These small choices also confront greater threats. They are often no less dangerous than more dramatic actions, as stories in this chapter make clear. As Vincent Van Gogh wrote, ‘The great is a succession of small things that are brought together.’

FLYING FREE

Around the world, many women choose to wear the headscarf for a mix of cultural and religious reasons. Others choose not to wear it. For both groups, that is their right. Some governments, however, are not keen on women exercising those rights.

Many Iranian women regularly defy the authorities with their ‘bad hijab’ – letting more hair show than the government believes is appropriate. The Iranian morality police – officially, ‘guidance patrol’ – rebuke or arrest 3 million women every year. In recent years, defiance has gone further – from bad hijab to no hijab, deliberately revealed to the world. In 2014, journalist and activist Masih Alinejad created a Facebook page where she photographed herself without a headscarf and encouraged other women to do the same, arguing that this was not about right or wrong, but about choice: ‘My mother wants to wear a scarf. I don’t want to wear a scarf. Iran should be for both of us.’

Women submitted their own images to the My Stealthy Freedom page, with hair uncovered and flying in the wind. As one woman put it, ‘We love Iran – and that is why we ask for more respect from our own country for women.’ The My Stealthy Freedom page has gained more than a million likes.

Other small acts of defiance continue to multiply. An app launched in 2016 crowdsources local information about where the ‘guidance patrol’ is operating on any given day. The app’s slogan: ‘Wander freely.’

Masih Alinejad is convinced time is on the women’s side. ‘The government is really scared of us. They’ve got weapons, they’ve got prisons, they’ve got money, they’ve got everything. We’ve got only Facebook. And that still scares them. Why? Because they don’t want women to be empowered. They don’t want women to be that loud.’

IN THE DRIVING SEAT

In Saudi Arabia, a country treated as a staunch ally by oil-thirsty Western governments, free speech is severely punished. Thus, to take just one example, prisoner of conscience Raif Badawi was sentenced in 2014 to a thousand lashes and ten years in jail, for the crime of expressing peaceful opinions online.

Women’s rights are trampled in a range of contexts. The Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia describes women driving as ‘a dangerous matter that exposes women to evil’. But Manal al-Sharif and other Saudi women are fighting back, including with videos of them defying the ban. Loujain al-Hathloul and Maysaa al-Amoudi, two of those who have disobeyed the rules, were briefly jailed in 2014 – after facing trial in a court designed for terrorism offences.

The pressure for change continues. Al-Hathloul’s husband, comedian Fahad Albutairi, is co-creator of a music video that echoed Bob Marley with its lyrics: ‘No woman, no drive.’ The video racked up 13 million views on YouTube. Albutairi quotes Oscar Wilde: ‘If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh – otherwise they’ll kill you.’

Saudi writer Maha al-Aqeel believes change is inevitable. ‘Many conservatives feel that if women get the right to drive, then that’s it, the last bastion of male control will fall. I think it should lead to other changes. That’s why those who oppose it are so vehement.’

Manal al-Sharif argues, ‘We are only a drop in this world. But the rain starts with a single drop.’

PEEING IN PEACE

There are many contexts in which people around the world are forbidden to make basic choices about their lives. In 2016, the governor of North Carolina, Pat McCrory, signed into law a bill that makes it illegal for a transgender person to use a bathroom that is not in accordance with the gender on their birth certificate.

The new bill caused a backlash, including cancelled performances by artists ranging from violinist Itzhak Perlman to Bruce Springsteen. PayPal cancelled plans for a global operations centre in North Carolina, while US Attorney General Loretta Lynch, herself born in the state, described the legislation as ‘state-sponsored discrimination against transgender individuals who simply seek to engage in the most private of functions in a place of safety and security’.

Meanwhile, in what one commenter described as ‘the best selfie ever’, Sarah McBride, LGBT communications manager at the Center for American Progress, posted a photograph of herself illegally in a women’s bathroom. Her caption declared, ‘They say I’m dangerous. And they say accepting me as the person I have fought my life to be seen as reflects the downfall of a once great nation.’ McBride saw it differently: ‘I’m just a person. We are all just people. Trying to pee in peace.’

POWER TO THEIR ELBOW

‘Nobody made a greater mistake than he who did nothing because he could only do a little.’

EDMUND BURKE

President Omar al-Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity and genocide, has ruled Sudan since 1989. He appears to believe he is undefeatable. During protests in 2012, al-Bashir mocked his critics, suggesting that they were ‘licking their elbows’ – a Sudanese phrase equivalent to ‘pigs might fly’ or ‘in your dreams!’

The activist group Girifna (‘We are fed up’) turned the phrase around to give it power of its own. Thousands photographed themselves in contorted positions, attempting to lick their elbows, and a few agile Sudanese succeeded in doing so. Defiant joint-licking images were posted and shared online.

Today, al-Bashir is still in power, not least after gaining an alleged ‘94 percent’ of the vote in 2015 (the opposition boycotted the poll, widely seen as unfair). Still, when al-Bashir’s rule finally comes to an end, elbow-licking may be seen as part of the mix that helped bring change.

WAVING A DIFFERENT FLAG

Cathy Freeman grew up with the prejudice that she and millions of Indigenous people had faced in Australia for many years. When she won her first running races at the age of ten, she received no medals. Medals went to white girls. Her own family history was marked by the suffering of what became known as the ‘Stolen Generations’, children forcibly removed from their families.

In 1994, aged twenty-one, Freeman became a national hero with her record-breaking 400-metre race for Australia at the Commonwealth Games. She decided her victory lap should be not just for her, but for all the Indigenous people of Australia. In defiance of the rules, she ran round the track with both the Australian and the Aboriginal flags.

‘There is no greater sorrow on earth than the loss of one’s native land.’

EURIPIDES

The head of the Australian team forbade her to repeat the action if she won the 200-metre race a few days later. Freeman did win. Again she wrapped herself in both flags. ‘This was my race, and nobody was going to stop me telling the world how proud I was to be Aboriginal.’ Freeman’s defiance rocked Australia. She received thousands of letters. A ninety-four-year-old woman wrote, ‘When I saw you run around with that flag, for the first time in my life I felt it was worth it all to be an Aborigine.’

Six years later, Freeman won gold again, at the Sydney Olympics in 2000. Before a jubilant home crowd, she repeated her victory lap wrapped in both flags. This time, there was no controversy. It was, as one commentator said, ‘a moment that united a divided nation’.

The momentum grew for a national apology for the suffering of the Stolen Generations, which Freeman herself had pressed for. In 2008, the apology finally came. On behalf of the state, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd conceded the ‘pain, suffering and hurt’ of the past. The future would be based on ‘mutual respect, mutual resolve and mutual responsibility’.

Freeman was photographed listening to the historic speech. As she listened, she wept. ‘We will never forget,’ she said. ‘But this allows us to forgive.’

PERIODIC PRESSURES

Governor Mike Pence of Indiana sounded proud when in 2016 he signed, with a prayer, an anti-abortion bill that was, in the words of one pro-choice organization, ‘one of the most vicious omnibus anti-abortion bills the United States has ever seen’.

The bill forbade abortion even in cases of severe disability. A woman who miscarries at eight weeks would be required to have the blood and tissue buried or cremated by a funeral home. In theory, a woman could be in breach of the new law by not burying her menstrual blood each month.

The women of Indiana had had enough. A Facebook page, Periods for Pence, was created, including email and phone details for the governor’s office. Women began phoning Pence’s office, taking advantage of his apparently detailed interest in obstetric and gynaecological issues, to let him and his colleagues know about their menstrual cycle, and to avoid getting unwittingly into trouble. ‘Hello, everything is flowing nicely this month, little heavier than normal,’ one woman told Pence’s office. Another reported that ‘my vagina and I had an ah-ma-zing weekend’. A third said, ‘I just wanted to inform the governor that things seem to be drying up today. No babies seem up in there. Okay?’

The stories multiplied – with serious implications, too. Planned Parenthood and the American Civil Liberties Union successfully challenged Indiana over what they argued was an unconstitutional bill.

In Poland, a proposed church-backed ban on abortion caused women to send equally graphic updates to the prime minister, along the lines of the action in Indiana. Many protested while waving coat hangers above their heads, a reminder of the dangerous abortions of the past. Describing a filmed mass walkout of women in response to a bishop’s message read out in Polish churches in April 2016, the Irish Times wrote, ‘The Middle Ages engaged in an unusual skirmish with the twenty-first century.’

NEO-NAZIS RAISE MONEY FOR GOOD CAUSE

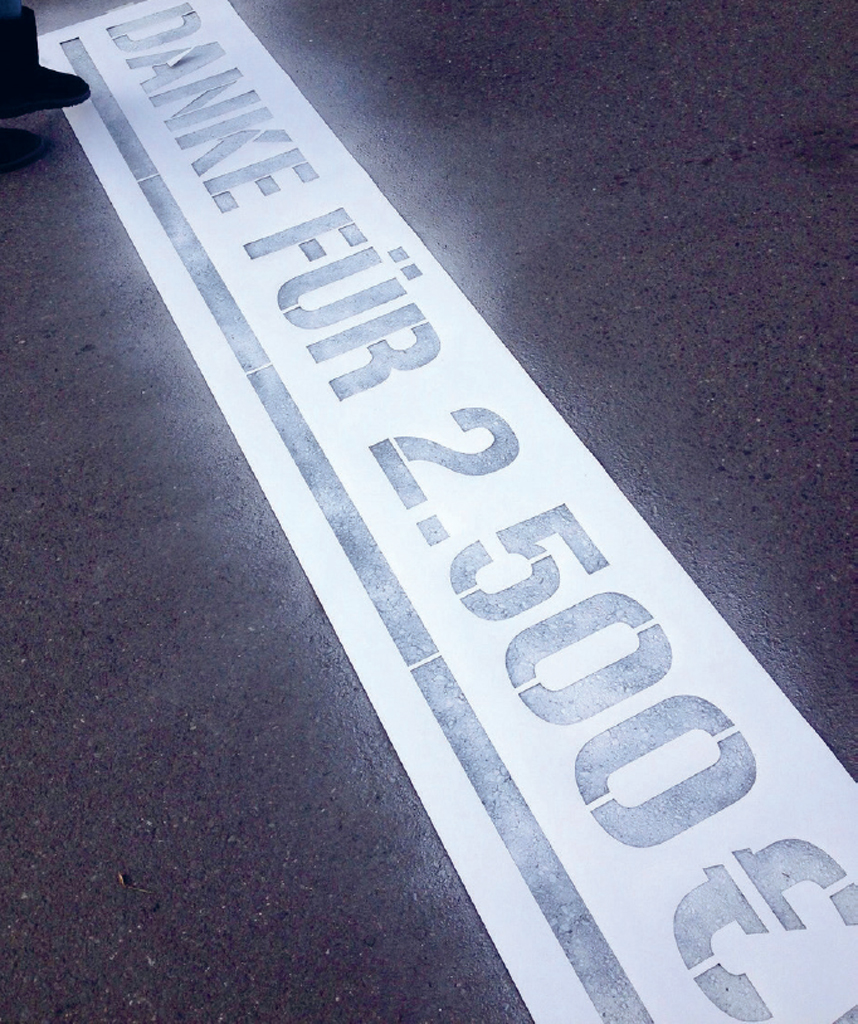

In past years, neo-Nazis have enjoyed marching through the small German town of Wunsiedel, to the despair of those who live there. (Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy, was at one point buried in Wunsiedel, hence the pilgrimage.) In 2014, locals decided they had had enough of the unwanted intrusion.

The organization Right Against the Right, working with residents and local businesses, came up with a plan: for every metre that the neo-Nazis walked, locals would donate €10 to Exit Deutschland, an organization dedicated to helping neo-Nazis leave their toxic ideas behind and reintegrate into society. The further the neo-Nazis walked, the more money the marchers would raise for the anti-Nazi cause. Enthusiastic banners along the way proclaimed the news. The neo-Nazis could go ahead with the march – and thus raise money for combating the far right. Or they could abandon the march – an equally good outcome, from Wunsiedel’s perspective.

The result: €10,000 to anti-neo-Nazism campaigns, and (in the words of the organizers) ‘lots of startled far-rightists’. Marchers received a certificate, praising them for their ‘outstanding achievement’ in raising money for a good cause. The Wunsiedel action has been replicated in towns across Germany, helping to unsettle and keep the brownshirts down.