OPERATIONAL DEPLOYMENTS

Between 1976 and 1978 I had a number of engagements against enemy forces inside Rhodesia and one significant encounter inside Mozambique. In this chapter I shall highlight my first and last operational deployments inside Rhodesia. The only engagement I had with the Rhodesian forces inside Mozambique shall be dealt with separately as a seminal chapter from my book ‘Chimoio Attack – Rhodesian Genocide’.

After completing my specialisation course in engineering in May 1976 I was appointed an assistant instructor under the supervision of an instructor who was a Member of the General Staff. When the first group of recruits I supervised in training concluded their basic training in guerrilla warfare around September 1976, my first opportunity for operational deployment presented itself. Operational commanders who had been promised reinforcements came to collect their fighters. The commander for Nehanda sector needed medical attention that might take up to a few weeks before he could be cleared to return to his operational area. It was decided that one of the assistant instructors, or veterans as we were referred to, be placed in command of a forty five member platoon that was allocated for deployment there. I happened to be the only one who knew the area well.

I was given my orders and the next two days were spent checking and ensuring the state of readiness of my troops. They were all kitted out with personal weapons that included AK-47s, hand grenades, bazookas – the Russian RPG-7s and Chinese RPG-2s – and 82 and 60mm mortars and their corresponding mortar bombs. Additionally, we were to carry ammunition reserves and anti tank and anti personnel mines. I then spent considerable time with the sector commander being briefed on how we were to penetrate the operational area and how we were to link up with other comrades deployed there. My deployment was to last not more than a month, after which I was to return and continue being an assistant instructor. While I would have preferred to have been deployed in Rhodesia for a much longer period, the prospect of my first deployment nevertheless filled me with great delight and would test my command capabilities.

On D-Day we were trucked northwards to begin our mission from a forward base in Tete province, just opposite Mukumbura in Rhodesia and about five kilometres from the border. As we crossed from Mozambique into Rhodesia, the excitement that had accompanied us up to the border was replaced by anxiety about what the first contact with the enemy would be like.

Our movements were mostly under cover of darkness, with rests during the day to avoid enemy detection. As we moved deeper inside Rhodesia, the freedom to speak loudly to each other was greatly curtailed lest the enemy should detect our presence. The efficiency with which this discipline was upheld and tolerated accentuated the degree of anxiety, or probably fear, that held my whole platoon captive. In fact, without being directed to do so, my platoon had replaced vocal communication with sign language, except in instances where speaking was unavoidable.

To ensure we remained on the right course to the target area, we had to align our direction to certain distinctive land marks like mountain peaks, large rivers, roads, and identifiable population areas.

It took us five days to get to our sector of operations. Every one of the comrades carried the standard personal issue – an AK-47 and webbing containing several hundred rounds of ammunition around the waist. In addition, we had four mortars and forty mortar bombs, two heavy machineguns, four light machineguns and cases of spare ammunition, which the platoon had to take turns in carrying. The three section commanders and I also had pistols.

During the time it took us to reach our sector of operations, night navigation proved a taxing experience. Visibility was very poor and limited to about eight metres, as the nights were dark and there was no moon. My ‘good knowledge’ of the area was mostly restricted to knowing the roads I had driven through in the past and the settlement areas I had once visited. In our march to the target area we avoided using the roads, for obvious reasons, and whatever landmarks I knew and relied upon were swallowed by darkness. We moved in single file, maintaining a gap of about five metres between each fighter. One could see only the comrade immediately ahead or the one immediately behind.

On several occasions in the darkest hours before dawn, a comrade would doze and veer off course. All those behind would blindly follow him on this wrong course. Sometimes, bringing the fighters back on course could take anything between one and two hours. The munitions that we carried were too heavy and stretched the platoon’s energy reserves to the limit. Each step taken up the mountains, down the steep slopes, along the valleys and across the plains, caused much physical pain and eroded the desire and confidence to confront the enemy.

During the day while we rested, we re-oriented our position and activated the mujibha/chibwido network as explained by the sector commander in his brief at the time I assumed command of the platoon. Through these essential contacts our platoon received adequate supplies of food and much valuable information about enemy movements and locations. This was clear testimony of the effectiveness of the ZANLA political orientation in forging a ‘fish and water’ relationship with the masses. These essential and welcome contacts with the masses helped to revive the sagging spirits of the combatants, but at the same time created a security risk as it was possible for the enemy to observe the increased activity between villagers and a particular section of the forest. Furthermore, there could be enemy informers amongst the civilian population.

On the second evening after crossing the border, misfortune struck. We were walking parallel to a deep gorge a few metres to our right at around 3.30 am when one of the comrades began to doze and veered off course. In full view of the comrade right behind him, he suddenly disappeared, swallowed by the ground beneath. Momentarily, the witness to this strange occurrence was immobilised by fear and superstition. All along he had known that it was foolhardy to challenge the might of the white men, and now the platoon was cursed.

At the same time these thoughts were racing through his mind, a shriek of pain erupted from beneath the ground that had swallowed his colleague, and he knew he had to run away before the curse visited him too. He threw away the gun and ammunition he was carrying as their combined weight would rob him of the speed he badly needed to get away. He broke away from the line, turned to the right, and ran for his life. The waiting gorge swallowed him too! Two sharp shrieks inside one minute alerted all the other comrades that something was wrong.

As standard procedure, they all took up prone positions with their guns cocked and ready to fire. They remained in this position as the commanders investigated the incident.

When the investigation was over and all the facts were established, what caused greatest concern to the platoon was the practical problem of having two stretcher cases, one with a fractured leg and the other with a swollen ankle and suspected fracture of the collar bone – in addition to the punishing weight of the munitions.

Under the circumstances we decided we could not proceed further that evening and the platoon took up positions on the nearby mountainside. Having administered first aid to the two injured comrades during the night, it became clear when daylight broke that their condition required specialist attention that could only be provided by our rear bases in Mozambique. We enlisted the services of eight mujibhas to carry the two injured comrades back to Mozambique, and I detached six members from the platoon to provide them with protection on their way back.

The third evening passed without incident, but on the fourth night as we were approaching our sector of operations, disaster struck again. We had been walking for over six hours when the lead comrade tripped over a sleeping buck. The man and the animal panicked at the same time. The animal took three or four leaps, stopped, and timidly looked around to see what had invaded his home.

The man had instinctively taken a prone position and cocked his gun, convinced he had stumbled on an enemy position. When the animal momentarily stopped, the man believed that the enemy was preparing to fire at him and resolved that he should be the first to fire. A burst of automatic fire erupted. The animal knew it now needed survival more than a home, and ran down along the line of combatants. Wherever it came into view of the fighters, it ignited gunfire.

Before the animal reached the end of the line it decided to cut across it, but with tragic consequences for our forces. As the gunfire followed the animal it passed through the heart of a section commander who was trying to halt the firing. Death was swift and painless. Even for the inexperienced fighters, however, it was evident that we had betrayed our presence to the enemy.

After burying our comrade in a shallow but well-camouflaged grave, I ordered the platoon to go and occupy defensive positions on a mountain slope about two kilometres away. As early as 6 am we were receiving a steady flow of information from our mujibha network about increased enemy activity around our position. By 7 am we could see the movement of some Rhodesian troops close to our position. It was about 8.20 am when the assault on our position began.

Judging by the volume of fire from my platoon, they had surely overcome their fear and were courageously confronting a much more seasoned force. On closer analysis of the effectiveness of our fire, I saw that about four comrades had not released their safety catches. They kept pressing their triggers, thinking that the sound of their colleagues’ guns was that of their own. A few others buried their faces in the ground and had their bullets ricocheting from a nearby rock.

The majority of the platoon had their weapons aimed high above the positions of the enemy. It was only after I stood behind them and threatened that I would shoot anyone who did not aim at the enemy that their aiming improved and our fire became more effective.

After an exchange of gunfire lasting almost an hour, there was a lull in the fighting and to my joy we had suffered no casualties. Satisfied that there would be no further attacks that day I ordered my troops at around 1730 hours to prepare for the resumption of our march forward to our intended destination. Just then, two enemy planes appeared out of the blue and dropped bombs on our position before disappearing in the direction they had come from. We were left licking our wounds and burying two of our comrades. The stark realities of war were vividly and painfully brought home to us. We all now understood better what we already knew but had not put into proper context; this was not a kid’s game of hide and seek but a dog eat dog contest.

Around 3.30 am of the fifth day we arrived in the Chawanda area, the same area I initially wanted to pass through to join the struggle inside the then Portuguese East Africa. That was the route my hero, Cuthbert, had told me to use in the hope of a chance encounter with comrades operating in the area.

Before leaving Mozambique on this mission the sector commander had cautioned me not to attempt on our own to establish contact with comrades operating in the area, as this could have disastrous consequences. Instead, I was given the name and description of a trusted civilian contact in the area that would organise our first encounter with other comrades. Leaving behind the rest of my platoon in defensive positions on a hillside, I took two comrades with me to locate the hut in Chawanda business centre where the trusted contact lived. It did not take us long to positively identify the hut. About twenty metres away from it, I left my AK-47 with my comrades and ordered them to cover my approach to the hut. I was armed with a pistol hidden beneath my shirt.

Fortunately the contact was there. I quickly introduced myself and ordered him to dress and follow me. Back at our platoon position I tasked him to arrange for a contact with other comrades operating in the area and warned him of the consequences of betrayal. It took less than 24 hours for my platoon to be united with our detachment that operated in the area.

For the one month I remained deployed inside Rhodesia we had three skirmishes with Rhodesian soldiers that regularly patrolled the area. However, the crowning moment of my deployment was when a Rhodesian troop carrier drove over an anti-tank mine I had planted on the dirt road – with spectacular results.

My last operational deployment inside Rhodesia was in March 1978, a few months after the attack by the Rhodesians on our ZANLA Headquarters at Chimoio, inside Mozambique. I shall describe in greater depth that attack in my next chapter. I was appointed to be one of the commanders of a 450 strong force that, for the past few weeks had been preparing for an attack on a big but as yet undisclosed target. Of this large force, fifty were female combatants. The size and composition of the force was significant in two respects. Firstly, this was the biggest ever ZANLA force mobilised to go and attack a single target. Secondly and more significantly, this was the largest mobilisation of female combatants to be deployed in a combat role. In the past, female combatants were used in a supportive role, carrying arms and ammunition to ‘safe’ locations at the periphery of the operational areas. From these locations their male counterparts would replenish supplies, but never before had women been deployed so deeply into the operational areas.

The timing of the attack, coming barely four months after the simultaneous attacks on Chimoio ZANLA Headquarters and Tembwe Training Base by the Rhodesians, was intended to send a powerful message that our ability to deliver fatal blows against the enemy had not been diminished by those attacks. To the contrary, our resolve to crush the repugnant regime of Ian Douglas Smith and his three stooges – Bishop Abel Muzorewa, Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and Chief Jeremia Chirau – had been strengthened and given added impetus.

A week before the mission was to begin, and in accordance with the directive from the Chief of Defence, Comrade Josiah Magama Tongogara, the Chief of ZANLA Operations, Comrade Rex Nhongo gathered the commanders who were selected to lead the operation. Amongst them, the most senior commander was Comrade Josiah Tungamirai.* Other members of the High Command included Comrade Tonderai Nyika, Comrade Ziso, Comrade Agnew Kambeu† and Comrade Dominic Chinenge. There were many members of General Staff, including Comrades Dragon Patiripakashata (the writer), John Walker, John Tekere, Sobhusa Gazi and Flint Magama.

The target was revealed to us as Umtali (now Mutare), the fourth largest town in Rhodesia and the provincial capital of Manicaland Province. A seven member team had just returned from a reconnaissance mission of the target and had been brought to brief us. Amongst them was Comrade Sobhusa Gazi.‡

From the border with Mozambique, the target lay within a 10 kilometre distance as the crow flies. Because of its proximity to Mozambique, a hostile country according to the Smith regime from where the main guerrilla movement operated, there was always heightened surveillance of the border area close to Umtali to thwart any attempts by ZANLA guerillas to spring attacks on the town. Brazen attacks had been successfully mounted against Ruda base about a year before the attack on Chimoio ZANLA Headquarters, and Grand Reef Airforce base about a month after the attack on Chimoio. Both these targets were in Manicaland and not very far from Umtali. Attacks on these heavily fortified bases proved our capacity and tenacious resolve to assault heavily guarded enemy bases. The Rhodesian regime knew that it was only a matter of time before a significant attack, such as the one we were contemplating, would be launched against major economic targets and population centres.

The reconnaissance team briefed us from a sketch map that showed enemy positions – military barracks, police camps, government buildings and industrial areas – as well as white and black residential areas, schools for white and black children, tourists’ attraction centres and hotels they frequented. The briefing even went into details of the rural areas that surrounded Umtali, including the local leadership – the chiefs, headmen and kraalheads. We even got to know who of these were sympathetic to the regime and who our staunch supporters were.

On a separate sketch diagram the reconnaissance group plotted the known static positions of the regime’s forces guarding the border, the areas they patrolled and their routine. Most importantly, they plotted the positions they wanted us to occupy when attacking our target and the recommended routes to get there.

Under cover of darkness we were expected to deploy astride the Christmas Pass* along the upper ridge of the mountain range lying in a north-easterly direction from the target. From these positions we would have a bird’s eye view of the target below. All the vital points we wanted to hit would be within range of our artillery, mortar fire and even small arms fire. Our positions would cut off the enemy’s main supply routes and likely direction of his reinforcements using the road leading to Harare or to Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) to the south west of Umtali. We decided we would deploy a reinforced platoon to lie in ambush on the road leading to Fort Victoria.

From the border the most direct route could take us not more than four hours to reach our target. However, choosing it would be suicidal as it was the most patrolled area and in some places the enemy had laid anti-personnel mines. The recommended route would first take us further away from our target, pass through rural areas where we enjoyed support and avoid those where there were sympathisers for the regime.

If all went according to plan we would be in attack positions within four to five days. Travel would be strictly under cover of darkness as our large numbers could easily compromise our presence and positions.

Once the target was neutralised, the bulk of the force would not return to Mozambique but would split and go to assigned operational areas as reinforcements. Only a platoon of around sixty would accompany Comrade Josiah Tungamirai back to our headquarters in Mozambique.

The next four days after being briefed about our mission were spent rehearsing our movements to the target and equipping our force with the necessary arms and ammunition. Each comrade was provided with food rations to last two days. Beyond that, we would depend on food supplies from our masses.

On the final day after checking that everything was in order, we issued operational orders and introduced the fighters to operational commanders who would take them to different operational zones as reinforcements once our target was neutralised.

D-Day arrived. There was a mixture of excitement and trepidation as we boarded the FRELIMO trucks that had arrived to take us and our supplies to a predetermined location close to the border with Rhodesia. As dusk settled, Comrade Rex Nhongo gave us a send off address in which he implored and inspired each and every comrade to demonstrate courage and commitment to our struggle. Depending on how we acquitted ourselves, Comrade Nhongo stressed, this could be a defining moment in our struggle.

As we crossed our Rubicon, the protective cover of darkness gave us a measure of security from the prying eyes of the regime’s security forces. But also, it induced a fear of the unknown and raised the spectre of lurking danger behind every bush and in every dark shadow.

My training and previous operational experiences had not prepared me sufficiently to appreciate the complexity of marching four hundred and fifty fighters through dark moonless nights, burdened by the punishing weight of arms and ammunition.

A direct approach to the target would take us between three and five hours, but the target would never be reached without falling prey to hungry enemy bullets and an intricate minefield. During the next three days we traversed the rural landscape first in a direction that took us further away from our target before veering towards it.

The reconnaissance had been accurate in its depiction of the terrain over which we would traverse. What it had overlooked or failed to highlight was that, while it was easy to conceal the movement of seven comrades, it was exceedingly more difficult, if not impossible, to conceal the movement of 450 comrades.

Wherever our forces set foot, we created tracks impossible to conceal but inviting to follow. Coordinating the movement of this huge force was a difficult task made more difficult by some comrades dozing during the march and veering off-course. Sometimes we had to delay our move to ensure everyone was accounted for.

Before day break we would have broken into companies and platoons and each platoon or company would camp by the hillside or mountain side. Commanders of the different unit formations would go to the main base where Comrade Tungamirai was, and we would coordinate our movement plans for the coming evening.

On our third day we were unable to reach the hills or mountains before daybreak. Worse still, we crossed the main road linking Umtali to Fort Victoria at the 18 kilometre peg to Umtali after the sun had risen. It took us longer than expected to cross the road because whenever we heard the sound of a vehicle we would lie low until it had passed.

Wherever we camped, it would not take long before our masses knew of our presence and start streaming to our positions with food and intelligence about enemy movements. There was so much excitement amongst our masses about such large numbers of guerrilla forces, and even more so about the inclusion of female fighters amongst us.

As per standard practice, we took advantage of these interactions with the masses to give political orientation and listen to their grievances. Political orientation was the vehicle we used to consolidate the fish and water relationship between the fighters and the masses.

Given the size of our force, maintaining the purpose of our mission a guarded secret could not be guaranteed. As it later emerged, some of the comrades had met their relatives in our daily interactions with the masses and, in strict confidence, warned them to leave Umtali because we were coming to attack it. Sometimes the chain of relations extended to members of the Rhodesian forces.

In the small hours of 19 March 1978, we arrived in the Gandayi area – about 15 kilometres to the west of our target. My unit of 64 comrades took up positions on a hillside in kraalhead Mazitu’s area. The central command position was located on a mountainside, about two kilometres from our position. Around 10 am I was accompanied by four comrades to go and attend our daily coordination meeting.

Everything was going according to plan. In fact, we were beginning to ridicule the enemy’s intelligence for failing to detect the movement of such a large group of fighters in over four days. Even the unusual movements of the masses as they came to our positions with food and to listen to our orientation did not seem to arouse the suspicion of the enemy.

By 1 pm we had finished our coordinating meeting and agreed that at dusk we would begin our final push to the target. We wanted to occupy attack positions by 3 am. The pounding of Umtali was expected to begin anytime between 3.30 am and 4.00 am and last not more than an hour. Once concluded, our force would disband into their respective reinforcement units and melt away.

The masses had already gathered by the time our coordinating meeting ended. Lots of food had been brought and more was still coming from the late comers. The comrades who had accompanied me and I were quickly served lunch before we returned to our base.

As we left the central command, Comrade John Walker, a member of General Staff, was singing to the assembled masses, “Sendekera mukoma Takanyu”. I never knew he could sing this song so well. The song was composed and popularised by comrade Murewa, also a member of General Staff, who was in the Transport Department. He could drive a lorry for many kilometres singing that one song and without repeating a verse. There were also two youths, Daniel, who died during the Chimoio attack, and Chikepe who survived the struggle, who could sing the song brilliantly. John Walker was electrifying his audience with the same intensity I had seen Daniel motivating the comrades at a parade a day before he was killed.

We had almost reached our base when we heard the unmistakable sound of an FN rifle, a weapon used by the enemy, from the direction of the central command. An experienced fighter will immediately tell if a bullet has found its mark by the quality of the echoing sound. If it is sharp like the clap of thunder, the target will have been missed. But, if it is a dull thud, it means an animal or human being has been hit. This was unequivocally a sharp sound. Although the enemy fire seemed to be targeted at our main command base, two of our other positions reacted to it by firing mortar bombs. There was no other gun fire from the enemy apart from the initial three short bursts. Without any waste of time we entered our base and radioed the central command.

“John Walker is dead,” was the shocking message we received.

Since the echo of the enemy fire suggested their target had been missed, and the only other fire was of our own mortar bombs, I concluded, and quite rightly too, that Comrade John Walker had been killed by friendly fire.

While I was at the central command my platoon had begun receiving through the mujibha nework reports of enemy sightings not very far from our base. Now, from our commanding positions on the hill, we could observe the enemy closing in. Surely, as we moved from the central command to our base we had been in the enemy’s sights and within range of his fire. But taking us out prematurely would have alerted those in the base to prepare for an enemy assault. Since we were moving into their killing zone anyway, the enemy was prepared to wait and take us out together – the commander and his troops.

I ordered my fighters to take up positions without delay. If we allowed the enemy to initiate fire, that would give them the psychological edge and bring panic to the majority of our untested fighters. In a very short space of time my comrades were in attack positions. I quickly inspected their positions, made sure they had sufficient ammunition and that the safety catches of their guns were released. Satisfied with our preparations, I took my position in the centre of my fighters.

The enemy forces were still moving towards our positions, oblivious that they had now entered our killing zone, when I opened fire. That was the signal for all my comrades to follow suit. As my fighters began firing, my own gun fell silent while I studied the effect of our fire and the reaction to it from the enemy. The enemy appeared to be in disarray, with a few returning our fire and the majority scrambling to seek cover. Evidently, command and control had been lost.

For almost forty minutes we dominated the fire fight and I was sure the battle would end soon unless enemy reinforcements arrived quickly. Celebration turned to panic, however, when three helicopters appeared above and started attacking our positions. There were also two spotter planes circling above us, directing the attacking planes to their targets. We directed our fire power towards the enemy planes until jet fighters also joined the fray and began bombing our positions. Now our own command and control was lost. Each one of us sought refuge in some cave, under boulders or in whatever cover or protection the terrain could offer.

As dusk turned to darkness the aerial threat disappeared. Even though there was no fire from the ground, one could not predict the next move by the enemy’s ground forces. We could not tell whether they had been obliterated, were in retreat, regrouping, or even attempting to sweep through our positions.

At first I feared the worst – that the majority of my fighters had either been killed or injured. To my relief, by midnight I had managed to account for all but two of my comrades. Miraculously, none of them had been injured. Fearing a follow-up assault when day broke, I repositioned my platoon on another nearby hill under cover of darkness.

It usually took us about three days to have an estimate of dead and injured enemy soldiers from the locals. The second day after the attack, before receiving feedback on casualty figures, I was ordered to report back to Chimoio Headquarters without delay. Before my departure for Chimoio, the planned attack on Umtali had been suspended and later aborted altogether, due to increased enemy deployments in the area.

When I arrived at Chimoio Headquarters I was informed that I was expected to report to our President and Commander-in-Chief, Comrade Robert Mugabe, in Maputo without delay. Arrangements were already in place for me to fly there. On my arrival in Maputo I immediately was taken to my President’s residence where I was informed that I was being re-deployed to Socialist Ethiopia as the Chief Representative of ZANU.

I had thus been withdrawn from the battlefield before knowing the fate of my two comrades, as well as the number of casualties we had inflicted on the enemy. It was only when I was in the middle of writing this book that I accidentally got sight of a report written by Comrade Tonderai Nyika,* then Provincial Commander for Manica operational area, on the last operation that I commanded.

From this report I was relieved to learn that my two missing comrades were later located unharmed and that we inflicted significant losses on the enemy.

ZANLA forces scored many operational successes and when the war ended in 1979 were in the process of consolidating and expanding liberated areas in many parts of the country. Amongst the many historic and daring achievements of ZANLA, I would like to single out a few for special mention.

The first battle that was fought by ZANLA forces against the Rhodesian forces, officially marking the beginning of the second Chimurenga, took place in Sinoia, now Chinhoyi, on 28 April 1966. This day is now remembered and celebrated as Chimurenga Day. On this day seven gallant ZANLA fighters* – Simon Chingosha Nyandoro, Christopher Chatambudza, David Guzuzu, Godwin Manyerenyere, Godfrey Dube, Chubby Savanhu and Arthur Muramba – fought fiercely against better equipped opponents who were using both ground forces and fighter planes. They stood their ground for two days until they ran out of ammunition. They all perished in this great battle. To their credit, they managed to bring down an enemy aircraft and cause a number of fatalities amongst the Rhodesian soldiers.

In December 1978 comrade Edwin Munyaradzi† led a unit of six guerillas that went to attack fuel tanks in Salisbury, the capital city and citadel of the regime’s might. The group smuggled weapons into the city by hiding them under tomatoes in vans travelling from Mutoko Tribal Trust Land. They lived in the high density suburb of Harare (now Mbare) and used local sympathisers to obtain transport to move around and reconnoitre their target and for shelter to rest and conceal themselves and their weaponry.

On 11 December 1978 at around 1800 hours they fired several RPG-7 rockets into the bulk storage tanks belonging to BP and Shell in the heavy industrial Southerton area. It was a huge publicity stunt for our struggle when the tanks exploded into a massive sheet of flame which billowed into the night sky. For nearly a week the fire raged on and Salisbury was covered by a fall out of black ash from the burnt fuel. The flames were finally extinguished with South African assistance. The spectacular and glorious inferno was a coup de grace for a regime that boasted of an impeccable and impenetrable intelligence network. The operation was planned and executed with the efficacy and finesse that is normally associated with fictional writing.

With their mission accomplished, our comrades were able to safely withdraw.

ZANLA had a clear policy on deployment which required every member of its forces, including Members of High Command, to have operational experience. This was done to avoid armchair management of the force. A demonstration of this policy was shown when Comrade Tongogara sent the Chief of Operations, Comrade Rex Nhongo (late General Mujuru) and the Deputy Political Commissar, Comrade Dominic Chinenge (General Constantine Chiwenga) who were all Members of ZANLA High Command, to sort out the problem of South African security forces who had been deployed in Mwenezi Range and were preventing the smooth advance of ZANLA forces in Gaza province towards the west. The two commanders moved into Rhodesia and then crossed into South Africa’s Vendaland where their forces started attacking South African security posts. The South Africans immediately withdrew from Mwenezi to their side of the border to improve their own security, thus leaving a clean passage for ZANLA to advance through. They thought it was Umkonto We Sizwe forces that were attacking their posts, and yet it was ZANLA.

The deployment of the ZANLA Political Commissar, Comrade Josiah Tungamirai (late Air Marshall and commander of the Airforce of Zimbabwe) to lead the 450 strong force assigned to attack Mutare is another case in point. To describe the innumerable successes and acts of valour by the ZANLA forces could fill volumes of books.

The author’s parents, Kanganiso Mujere Mutambara and Karukai Elizabeth Mutambara.

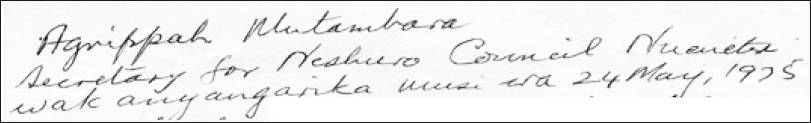

The diary entry of the author’s father reads: “Agrippah Mutambara, Secretary for Neshuro Council, in Nuanetsi, disappeared on 24 May 1975.”

Commando Group under training. Instructors in the front row are, from left: Cde Chibede, Cde Zitterson Zuluka, Cde Oliver Shiri and Cde Dragon Patiripakashata (the author).

The Nyadzonya massacre, 1976.

Buildings damaged in the Chimoio attack, November 1977.

Cde Josiah Magama Tongogara, ZANLA Chief of Defence.

Josiah Tongogara (with AK, at left) rescuing Ruvimbo Mujeni at Chimoio, November 1977.

A mass grave of those who died at the hands of the Rhodesians, Chimoio, November 1977.

The mobile theatre at Chimoio’s Parirenyatwa clinic, clearly marked with a red cross, with the bodies of slaughtered medics in front.

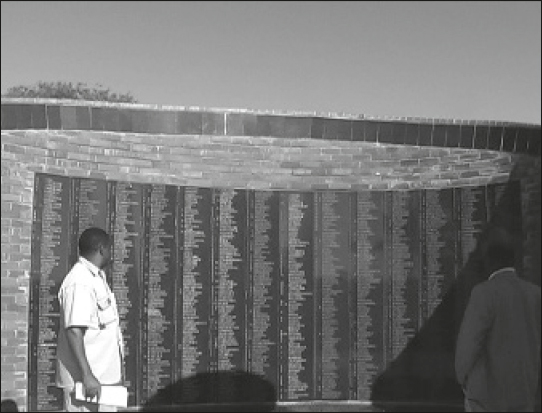

Top & center and above: The monument and mass graves at Chimoio, built after independence.

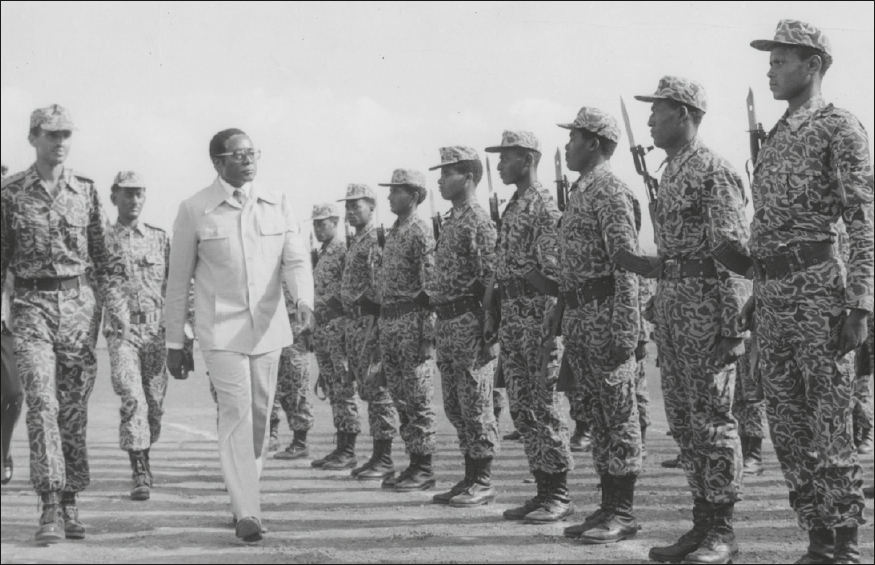

Cde Robert Mugabe inspecting quarter guard mounted by Ethiopian instructors at Tatek.

Cde Mugabe writing a message to be sent by radio to forward units. Behind him is the author (in dark suit and spotted tie) and to his right in a lighter suit, with sunglasses, is Josiah Tongogara.

Chairman Mengishtu presenting a pistol to the overall best recruit.

Operational report dated 10 April 1978.

Chairman Mengishtu (with fatigue cap, centre) inspecting a parade mounted by ZANLA recruits.

Cde Mugabe with the chief Ethiopian instructor. Behind them are Cde Dragon Patiripakashata (the author) in dark suit, Cde Tongogara to his immediate left and Cde Martin Macharanga (with briefcase).

Cde Vivian Mwashita hands Cde Mugabe a radio message.

Chairman Mengishtu, flanked by Colonel Afework and Cde Mugabe, responding to slogans at a military rally.

President Robert Gabriel Mugabe.

ZANU Chairman, Herbert Wilshire Chitepo, who directed the armed struggle and was killed by a car bomb in Lusaka, Zambia on 18 March 1975.

Cde Mugabe flanked by Major Darwitt (Foreign Affairs) to his right and Colonel Afework (camp commander) to his left. Behind Mugabe is Josiah Tongogara who is flanked by Cde Victor Mhizha to his left and the author to his right. Cde Danford Munetsi is holding a briefcase.

In July 1979 all ZANU’s chief foreign representatives were recalled to Maputo for an intensive briefing in order to intensify ZANU’s diplomatic offensive. President Mugabe is flanked by Vice-President Simon Muzenda on his right and Secretary-General Edgar Tekere on his left. Front row (sitting) from left: Cde J. Chimbande (Tanzania), Cde L. Maziwisa (Romania) and Cde J. Mandebvu (Libya); second row (kneeling) from left: Cde J. Kangai (USA), Cde A. Chidoda (Canada), Cde R. Chivhiya (West Africa) and Cde J. Shoniwa (Sweden); back row (standing) from left: Cde D. Patiripakashata (Ethiopia), Cde F. Shava (UK); Cde Mombeshora (Egypt), Cde S. Makoni (West Germany), Cde Simbarashe (Australia) and Cde M. Chademana (Botswana).

General ‘Tongo’, all-round commander and military strategist par excellence, in combat pose.

Cde Rex Nhongo, a brave, fearless fighter.

* Comrade Josiah Tungamirai joined the Armed Forces and rose to the rank of Air Marshal. He was the first black Airforce Commander. He died of natural causes after retiring and was declared a national hero.

† Comrade Agnew Kambeu, after independence, reverted to the use of his real name, Ammoth Chimombe. On Independence Day in 1980 he hoisted for the first time the Zimbabwe flag. He served in the Zimbabwe National Army and retired as a Lt. General. He was declared a national hero and is buried at the National Heroes Acre.

‡ Comrade Sobhusa Gazi (real name Gula Ndebele) served in the army after independence. He was later to become Attorney-General.

* Christmas Pass is a mountain pass that leads into the city of Mutare in Zimbabwe. It was so named by some of the colonial pioneers who camped at the foot of the pass on Christmas Day, 1890.

* After independence, Comrade Tonderai Nyika (real name Paradzai Zimondi) joined the Zimbabwe National Army. He retired with the rank of Major General and was appointed Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Prison Services.

* The names of the Sinoia seven are as corrected in the new edition of The Struggle taken from the Heroes Acre publication.

† Comrade Edwin Munyaradzi (real surname Chitekedza) joined the Zimbabwe National Army after independence and retired with the rank of Brigadier General. He died and was declared a National Hero.