National Parks & Reserves

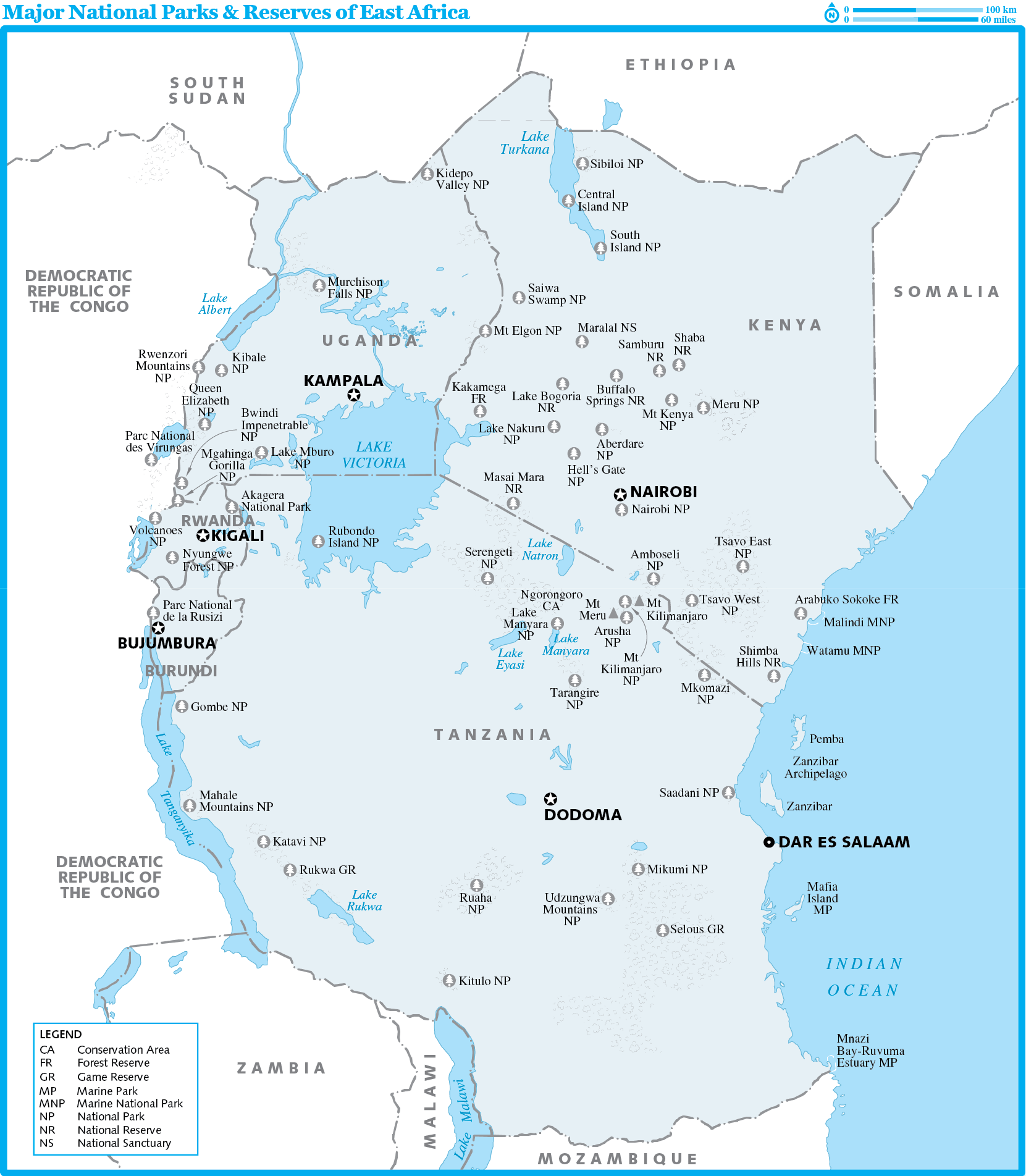

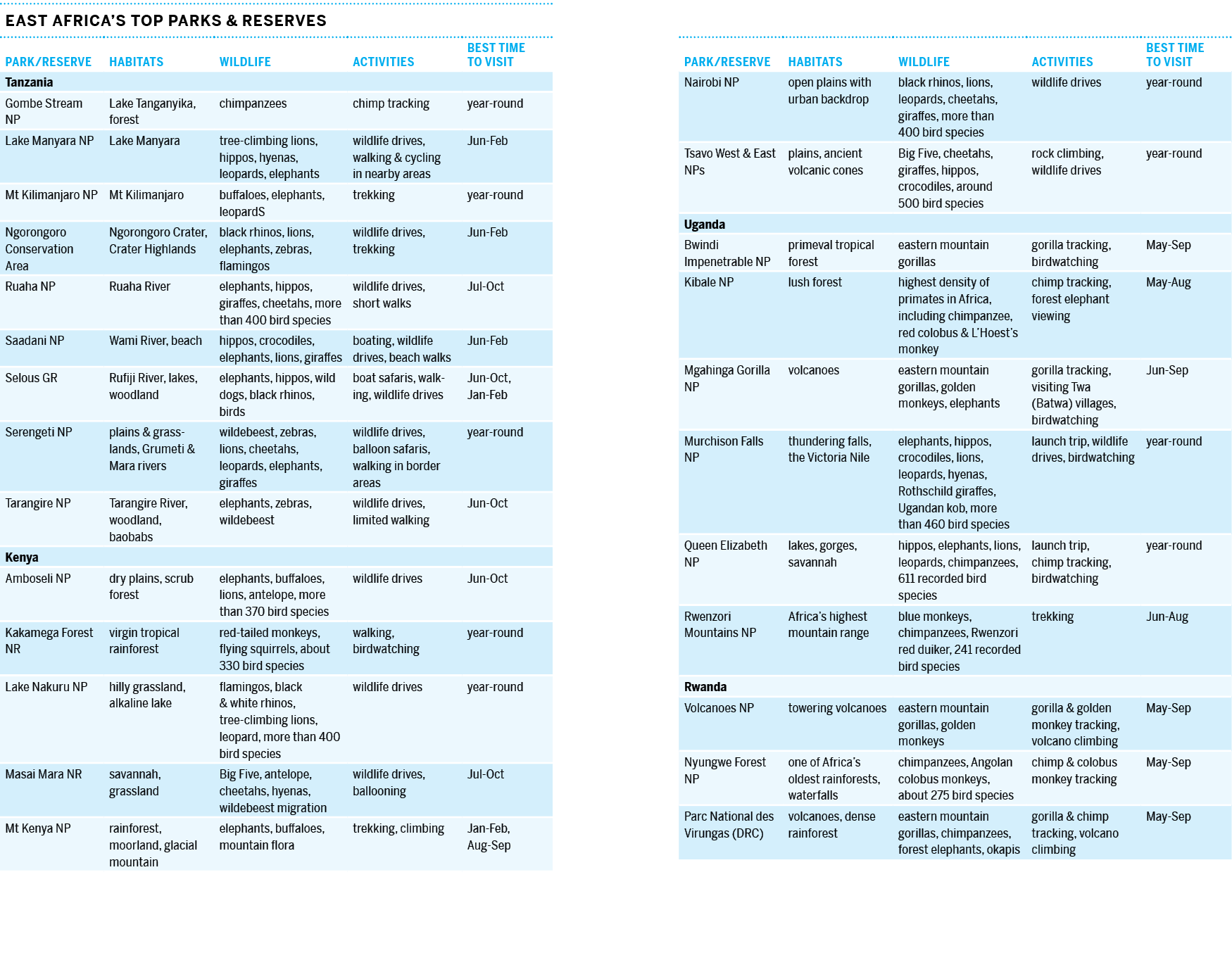

East Africa’s national parks and reserves rank among the best in Africa and some of the parks – Serengeti, Masai Mara and Mt Kilimanjaro to name just three – are the stuff of travellers' lore. Although some of the parks are under siege, and as much as 75% of the region's wildlife lives outside the protected areas, the region's national parks have, almost single-handedly, ensured that East Africa endures as one of the last remaining repositories of charismatic megafauna left on the planet.

History

The idea of setting aside land to protect nature began during colonial times, and in many cases this meant forcibly evicting the local peoples from their traditional lands. Enforcement of any vague notions of conservation that lay behind the reserves was often lax, and local anger was fuelled by the fact that many parks were set aside as hunting reserves for white hunters with anything but conservation on their minds. Many of these hunters, having pushed some species to the brink of extinction, later became conservationists and by the middle of the 20th century, the push was on to establish the national parks and reserves that we see today.

Africa's oldest national park is Parc National des Virungas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); it was set aside by by the Belgian colonial authorities in 1925. It was more than 20 years later, in 1946, that Nairobi National Park became East Africa's first such officially protected area.

Visiting National Parks & Reserves

Tanzania

With more than one-third of Tanzanian territory locked away as a national park, wildlife reserve or marine park, Tanzania has the widest selection of protected areas to choose from.

Park entry fees range from US$30 to US$100 per adult per day (US$10 to US$20 per child per day), depending on the park, with Serengeti, Kilimanjaro, Mahale Mountains and Gombe parks the most expensive.

Except at some of the less-visited parks, where credit-card machines are planned, all park fees must be paid electronically with a Visa card or MasterCard. It's also possible to pay using a ‘smart card’ available for purchase from CRDB and Exim banks. Just in case, always bring both Visa or MasterCard as well as US dollars in cash or the equivalent in Tanzanian shillings (the latter to cover cases where the card machines are non-existent or not working).

Kenya

Kenya has 22 national parks, plus numerous marine parks and national reserves. Entry to some marine parks starts at US$20 per adult (US$15 per child) per 24 hours, while mainland parks start at US$25 (US$15 per child) and reach as much as US$80 (US$45 per child) for the Masai Mara National Reserve. Vehicles cost extra, with US$10 per day the norm.

In theory you pay your park entry fees with cash or a credit card. We strongly recommend that you pay in US dollars or Kenyan shillings, as KWS exchange rates are punitive. When it comes to credit cards, you'll often find the connection to be down so always carry enough cash with you to cover all the necessary fees.

Uganda

More than one-quarter of Uganda is protected in some form, with a particularly rich concentration of protected areas in the country’s southwest. Most national parks charge US$40 per adult (US$20 per child) per 24 hours, with additional charges for vehicles, nature walks and ranger-guides; 20% of park fees go directly to local communities. Payments can be made in Ugandan shillings, dollars, euros and pounds in cash or travellers cheques (1% commission). And remember that if you’re here to track gorillas, the US$600 permit fee includes park entry fees.

Rwanda

Rwanda has three national parks worthy of the name and entry fees depend on the reason for your visit. A permit to track the gorillas in Volcanoes National Park costs US$750, which includes park entry fees. Tracking chimpanzees (US$90) or golden monkeys (US$100) is considerably cheaper. Payments are usually made in cash, and preferably in US dollars.

Burundi

Burundi has three national parks, although visitor facilities are basic to non-existent and visitors are just as rare. Each of the parks is best visited as part of an organised safari arranged in Bujumbura. As always in Burundi, check the security situation before setting out.

The Conservancy Model

In Kenya, and increasingly in Tanzania, some of the most important conservation work is being done (and some of the most rewarding conservation tourism experiences are to be found) on private or community land.

Private Conservancies

The conservancy idea took hold on the large cattle ranches on Kenya's Laikipia Plateau and surrounding areas. One of the first to turn its attention to conservation was Lewa Downs, now the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, which in 1983 set aside part of its land as a rhino sanctuary. There are now more than 40 such conservancies scattered across Laikipia and northern regions, with more around the Masai Mara.

The conservancy model differs from government-run national parks and reserves in a number of important ways:

- Nearly all conservancies focus on both wildlife conservation and community engagement and development; the conservancy entrance fees directly fund local community projects and wildlife programs. By giving local communities a stake in the protection of wildlife, so the argument goes, they are more likely to protect the wildlife in their midst.

- Access to conservancy land is, in most cases, restricted to those staying at the exclusive lodges and tented camps; Kenya's Ol Pejeta Conservancy is a notable exception. The result is a far more intimate wildlife-watching experience.

- Most private conservancies offer far more activities (including walking,horseback safaris and off-road driving) than national parks.

Tanzania has two private conservancies: Manyara Ranch Conservancy (www.manyararanch.com), between Lake Manyara and Tarangire National Parks, and the Kilimanjaro Conservancy (![]() %0754 333550, 027-250 2713; www.thekiliconservancy.org), in the West Kilimanjaro region.

%0754 333550, 027-250 2713; www.thekiliconservancy.org), in the West Kilimanjaro region.

Community-Run Conservancies

Community conservancies are an extension of the private conservancy model. Rather than being owned by wealthy landowners or families, community conservancies are owned by entire communities and administered by community representatives. With financial and logistical support from outside sources, these communities have in many cases built ecolodges whose income now provides much-needed funds for their education, health and humanitarian projects.

Northern Kenya appears to provide particularly fertile ground for the community conservancy model, but there are also some excellent examples around Amboseli National Park and in the Masai Mara region.