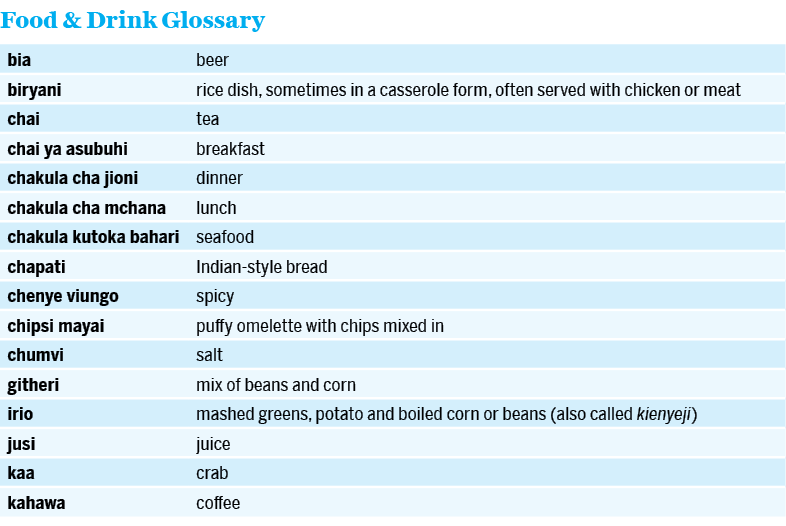

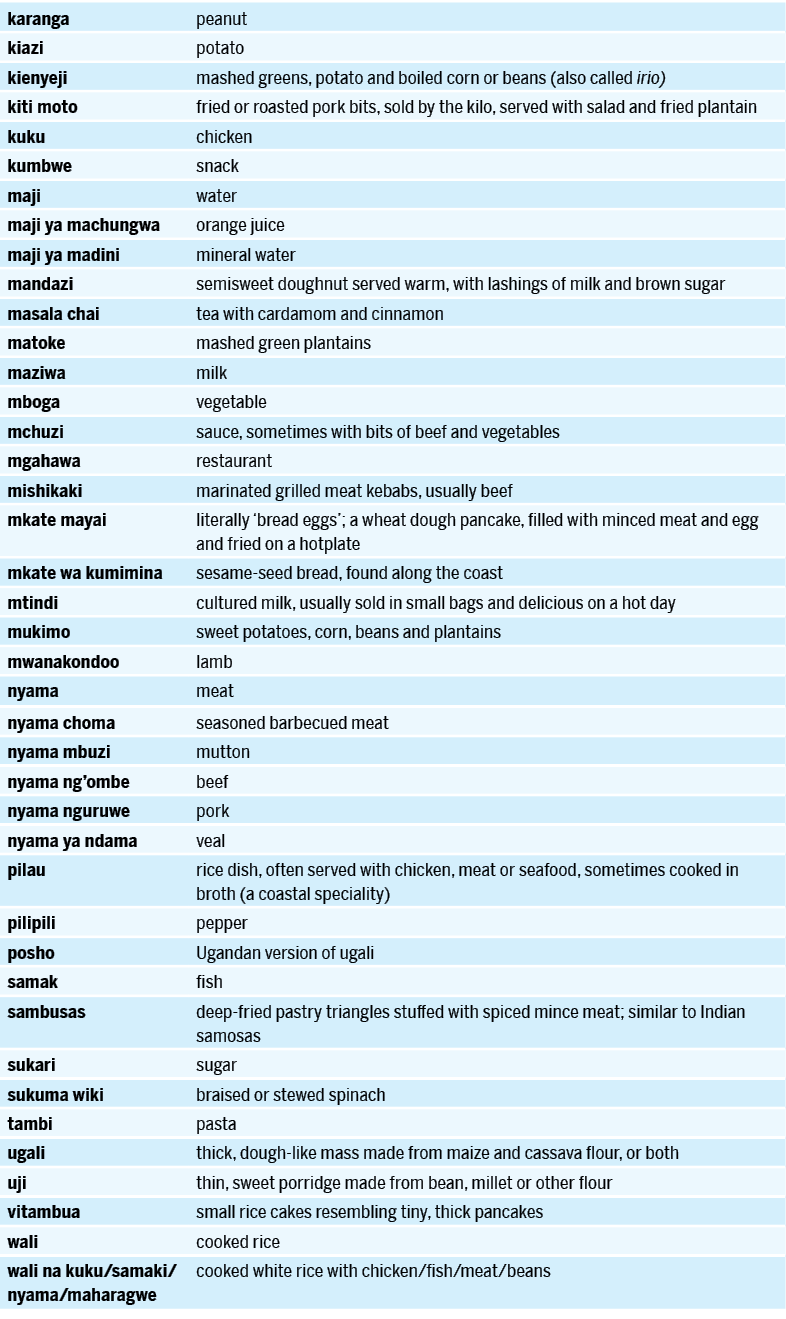

A Taste of East Africa

East Africa's culinary tradition has generally emphasised feeding the masses as efficiently as possible, with little room for flair or innovation. Most meals centre around ugali, a thick, dough-like mass made from maize and/or cassava flour. While traditional fare may be bland but filling, there are some treats to be found. Many memorable eating experiences in the region are likely to revolve around dining alfresco in a safari camp, surrounded by the sights and sounds of the African bush.

The Street-Food Scene

Whether for the taste or simply the ambience, the street-food scene is one of the region’s highlights. Throughout East Africa vendors hawk grilled maize, or deep-fried yams seasoned with a squeeze of lemon juice and a dash of chilli powder. Along the coast pweza (octopus) kebabs sizzle over the coals, and women squat near large, piping-hot pots of sweet uji (millet porridge). Other East African streetside favourites include sambusas (deep-fried pastry triangles stuffed with spiced mince meat) – but be sure they haven’t been sitting around too long – maandazi (semi-sweet doughnut-like products) and chipsi mayai (a puffy omelette with chips mixed in). Nyama choma (seasoned barbecued meat) is found throughout the region and is especially popular in Kenya.

Ugali & Other Staples

One of the most common staples in East Africa is ugali (a thick, filling dough-like mass made from maize or cassava flour, or both); it’s known as posho in Uganda. Around Lake Victoria, the staple is just as likely to be matoke (cooked plantains), while along the coast rice with coconut milk is the norm. Whatever the staple, it’s always accompanied by a sauce, usually with a piece of meat – often a rather tough piece of meat – floating around in it.

WE DARE YOU

If you’re lucky (!) and game (more to the point), you may be able to try various cattle-derived products beloved of the pastoral tribes of Kenya, Tanzania and elsewhere. Samburu, Pokot, Maasai and Karamojong warriors all have a taste for cattle blood. The blood is taken straight from the jugular, which does no permanent damage to the cattle. Mursik is made from milk fermented with grass ash, and is served in smoked gourds. It tastes and smells pungent, but it contains compounds that reduce cholesterol, enabling the warriors to live quite healthily on a diet of red meat, milk and blood.

Vegetarian Cuisine

While there isn’t much in East Africa that is specifically billed as ‘vegetarian’, you can find cooked rice and beans almost everywhere. The main challenges are keeping dietary variety and getting enough protein. In larger towns, Indian restaurants are wonderful for vegetarian meals. Elsewhere, Indian shop owners may have suggestions, while fresh yoghurt, peanuts and cashews, and fresh fruits and vegetables are all widely available. Most tour operators are willing to cater to special dietary requests, such as vegetarian, kosher or halal, with advance notice.

Drinks

Water & Juice

Tap water is best avoided; also be wary of ice and fruit juices that may have been diluted with unpurified water. Bottled water is widely available, except in remote areas, where it’s worth carrying a filter or purification tablets.

Sodas (soft drinks) are found almost everywhere. Freshly squeezed juices, especially pineapple, sugar cane and orange, are a treat, although check whether they have been mixed with safe water. Also refreshing, and never a worry hygienically, is the juice of the dafu (green) coconut. Western-style supermarkets sell imported fruit juices.

Coffee & Tea

Although East Africa exports high-quality coffee and tea, what’s usually available locally is far inferior, and instant coffee is the norm. The situation is changing in major cities and tourist areas, albeit slowly. Both tea and coffee are generally drunk with lots of milk and sugar. On the coast, sip a smooth spiced tea (masala chai) or sample a coffee sold by vendors strolling the streets carrying a freshly brewed pot in one hand, cups and spoons in the other.

Beer & Wine

Among the most common beers are the locally brewed Tusker, Primus and Kilimanjaro, and South Africa’s Castle Lager, which is also produced locally. Many locals prefer their beer warm, especially in Kenya, so getting a cold beer can be a task. Good-quality South African wines are readily available in major cities.

Locally produced home brews (fermented mixtures made with bananas or millet and sugar) are widely available. However, avoid anything distilled; in addition to being illegal, it’s also often lethal.

Dining Out

Hotelis & Night Markets

For dining local-style, find a local eatery, known as hoteli in Swahili-speaking areas. The day’s menu, rarely costing more than US$1, is usually written on a chalkboard. Rivalling hoteli for local atmosphere are the bustling night markets, where vendors set up grills along the roadside and sell nyama choma (seasoned barbecue meat) and other street food.

Restaurants

For Western-style meals, cities and main towns will have an array of restaurants, most moderately priced compared with their European counterparts. Every capital city has at least one Chinese restaurant. In many parts of East Africa, especially along the coast, around Lake Victoria and in Uganda, there’s also usually a selection of Indian cuisine, found both at inexpensive eateries serving Indian snacks, as well as in pricier restaurants.

Self-Catering

Supermarkets in main towns sell imported products, such as canned meat, fish and cheese.

Local Customs & Traditions

Typical East African style is to eat with the right hand from communal dishes in the centre of the table. It is not customary to share drinks. Children generally eat separately.

European-style restaurant dining, while readily available in major cities, is not an entrenched part of local culture. More common are meal-centred gatherings at home to celebrate special occasions.

Lunch is served between noon and 2.30pm, and dinner from about 6.30pm or 7pm to 10pm. The smaller the town, the earlier its dining establishments are likely to close; after about 7pm in rural areas it can be hard to find alternatives to street food. During Ramadan, many restaurants in coastal areas close completely during daylight fasting hours.

DINING EAST AFRICAN STYLE

If you’re invited to join in a meal, the first step is hand washing. Your hostess will bring around a bowl and water jug; hold your hands over the bowl while she pours water over them. Sometimes soap is provided, and a towel for drying off.

At the centre of the meal will be ugali or some other similar staple. Take some with the right hand from the communal pot (your left hand is used for wiping – and we don’t mean your mouth!), roll it into a small ball with the fingers, making an indentation with your thumb, and dip it into the accompanying sauce. Don’t soak the ugali too long (to avoid it breaking up in the sauce), and keep your hand lower than your elbow (except when actually eating) so the sauce doesn’t drip down your forearm. Eating with your hand is a bit of an art and may seem awkward at first, but after a few tries it will start to feel more natural.

The underlying element in all meal invitations is solidarity between the hosts and the guests. If you receive an invitation to eat but aren’t hungry, it’s OK to explain that you have just eaten. However, still share a few bites of the meal in order to demonstrate your solidarity with the hosts, and to express your appreciation.

Don’t be worried if you can’t finish what’s on your plate; this shows that you have been satisfied. But try to avoid being the one who takes the last handful from the communal bowl, as your hosts may think that they haven’t provided enough.

Except for fruit, desserts are rarely served; meals conclude with another round of hand washing.