IT’S NEAR THE END of December, but southeastern Wisconsin has yet to see much snow so far this winter. The day is gray and over-cast and the temperature persistently stable at thirty-two degrees. Bundled up and well layered, Sue and I set out to hike a segment of the Ice Age Trail, the thousand-mile-long National Scenic Trail that winds through Wisconsin from near Lake Michigan in the east to the Minnesota border in the west. We’re starting what our Ice Age Trail Alliance chapter calls the “Walk the Wauk” program. By this time next year—or quite a bit sooner, we hope—we’ll have walked approximately forty-five miles of the Ice Age Trail here in Waukesha County at least once and, given the likelihood of our hiking out and back, probably twice. The seasons will have changed considerably by the time we’ve covered our county’s portion of the trail.

We won’t hike the county segments in order, in a determined march from one end to the other, though we do start at the northern limit, near Monches, at the Washington County line. A sign at the northern trailhead for the Monches segment tells us we’re about to enter the Carl Schurz Forest, named for an early Wisconsin conservationist. Carl Schurz was born in Germany and in 1855 settled in Watertown, Wisconsin, in nearby Jefferson County. There his wife, Margarethe Schurz, founded the first kindergarten in North America, modeled on that of Friedrich Fröbel in Germany. Schurz was a lawyer and politician in Wisconsin, a major general in the Union army during the Civil War, a US senator from Missouri, and secretary of the interior from 1877 to 1881.

As secretary, Schurz decried the depletion of forests on public land by private lumbering companies and initiated the first federal forest reserves, essentially starting the movement toward a national forest service and a national park system. During Schurz’s childhood in Germany, his father had managed the forests of Count Metternich, and Schurz once declared, “I learned to love the woods and to feel the fascination of the forest-solitude, with the whisper of the winds in the treetops.” I don’t know whether Schurz ever saw this stretch of forest—probably not—but I like the fleeting sensation of this forest harking back to forests across centuries and continents.

We leave the trailhead and climb a slope, traipsing through a narrow wooded corridor. Open farmland is hidden to the west by the top of the rise and obscured to the east by trees lower down the slope. Soon the woods expand into oak forest, generations of oak leaves making the forest floor a tan and brown kaleidoscope. The canopy, open now in winter, is high above us. Often we descend into a swale, or depression, with high ridges cutting off the horizon, the trail winding through the forest, rolling up and down. We hear no wind in the treetops, but the forest solitude is enough to make me think Carl Schurz might have liked walking here.

It takes a geological imagination to recognize what we’re hiking on as the result of glaciation ten thousand years ago, and part of the point of walking the Ice Age Trail is to get acquainted with the glaciers and what they wrought. I’ve consulted The Ice Age Trail Companion Guide to briefly prepare me for where we’ll be and Geology of the Ice Age National Scenic Trail to keep me thoroughly apprised of how it came to be there. The latter book, by David Mickelson, Louis Maher, and Susan Simpson, is particularly thorough and conscientious, and, even if my grasp of glaciation or geology always seems tentative and superficial, I’m gaining an awareness of what glacial forces shaped the landscape under the Ice Age Trail.

The Monches segment begins in the valley of the Oconomowoc River, which meanders through what once was a wide glacial meltwater channel. The river itself is not visible from the forest but arcs around the eastern side of Monches, through the inevitable millpond marking where the village began; the Ice Age Trail won’t cross it until about a third of the way through the segment. The oak forest has grown on what the geology book identifies as “high-relief hummocky topography.” This means that, when glacial ice melted, sediment that deposited on top of it, in varying thicknesses, settled onto earlier deposits to form an uneven landscape, sometimes in high relief, sometimes in low relief. The meltwater channel cleared and leveled the ground it passed over, and the river that succeeded it carved its own channel lower into the floodplain, leaving relatively flat terraces on either side. Of course, to see all this occurring would require time-lapse photography covering thousands of years—the scale and scope of Ice Age glaciation would never be obvious to a bystander in any of those millennia.

Eventually we come down out of the forest, veering through a grassy field and into denser, younger forest as we near the Oconomowoc River. The water is clear, shallow, and undoubtedly cold, often interrupted by dead trees and fallen branches that teeter across exposed boulders. The riverbed in some places is thoroughly rock-strewn, and the banks are low enough that they don’t drain well. In wet years a long stretch must be persistently waterlogged. Though we’ve had little snow, we’ve had plenty of cold—in some places small ponds are simply iced over and in others, water flows from beneath rugged canopies of ice. Just before a long narrow agricultural field, a high wooden bridge arches over the river and a series of boardwalks and puncheons extends through the floodplain forest on the eastern side. The bridge and boardwalk are new, a restoration project by a volunteer work crew of the Ice Age Trail Alliance. It’s easy to see that a combination of heavy snowmelt and spring rains could make the lowlands mucky and saturated. A low terrace that will take us to the end of the segment gives us drier footing, and more puncheons sometimes guide us over the lowest parts of the trail.

Except for occasional yellow blazes on trees to mark the trail, until we reach the bridge we have little sense of a world outside the forest. But coming out of the lowlands, the forest narrows again and we notice houses not far beyond the top of the slope, perched on a higher terrace. Often driftwood, tree limbs, and trunk sections are piled at the border between the private yards and the woods; a couple of times we pass overturned canoes. We’ve seen few other people on the trail, but those we have—a couple of mothers with their children—make us realize that the Ice Age Trail, at least in this segment, offers some very accessible recreation for nearby homeowners. The women and children were lightly layered, all of them in sneakers, chatting casually as they ambled along, comfortably strolling what to them was home ground. With our hiking boots and daypacks and steady, determined pace, we felt a little melodramatic about our appearance, our outsider status uncomfortably obvious.

Past the houses the wooded corridor narrows still further, even as the river widens. Fields and farmlands spread off to the east; west of the woods the floodplain opens up into sprawling wetlands filled with thick, tall, tangled brown grasses. Exposed to the sky, the river takes on a placid, bright gray gleam as it curves through the grasses into the distance.

Soon we come to another expanse of oak forest, younger than the Schurz Forest, more studded with saplings. We cross a small creek on a low, flat bridge and pass a Leopold bench with a memorial marker: “These Woods Are Where My Spirit Lies . . . When You Are Lost, Come Here And You Will Find Me.” We started the walk at the sign honoring Carl Schurz, so it doesn’t surprise me to find another memorial on the trail, but I keep thinking about it as we walk on. Something about this personal commemoration seems more difficult to achieve in the commemoration of a public figure. Whether the man memorialized in the bench marker ever said anything close to what’s inscribed there, the memorial has a reciprocal effect: it honors not only the man but also the place that mattered to him. There’s something elevating in the association for man and forest alike that cemetery headstones and public monuments can’t capture. To his friends and family, some part of him is still here on what he felt to be his home ground.

We are close enough to County Highway Q, a stretch of the Kettle Moraine Scenic Drive, to hear the traffic. It pulls us away from glacial reflection. Soon the trail curves around a high embankment for the railroad and emerges in view of a long concrete overpass that the train tracks cross. One of the three arches in the overpass, close to the trailhead, serves traffic on the road, and another serves the river, which continues on its way south. We stand near the sign for the southern trailhead of the Monches segment, sipping water and noticing local traffic. In that moment it’s clear that, no matter how much it’s the glacial terrain that lures us out onto the trail, the present is too much with us for us to imagine for long that we’re walking in the past.

It’s humbling to confess, after spending more than four-fifths of my life in glaciated Great Lakes states, a good portion of that time writing and teaching the literary nonfiction of place, that I have only lately begun to pay attention to glaciers. In spite of their having left Wisconsin around ten thousand years ago, I seem to be constantly aware of them, constantly struggling to tune my senses to their former existence upon my present home ground.

I’ve tried to anchor my understanding more solidly by taking Marlin Johnson’s continuing education class in the glacial geology of Waukesha County; I’ve heard David Mickelson, an author of the book I constantly consult, lecture on the glacial geology of the Ice Age Trail; I’ve tracked down some of the sources that Johnson and Mickelson have drawn upon, like Lee Clayton’s Pleistocene Geology of Waukesha County, Wisconsin. Clayton’s abstract for his Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey Bulletin very succinctly sets the stage: “Waukesha County, in southeastern Wisconsin, straddles an area that was the junction of the Green Bay and Lake Michigan Lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Wisconsin Glaciation. Most of the topography of Waukesha County formed during this glaciation.” I may not always know what glacial remnants are beneath my feet, but I’m constantly aware that they are there.

The eastern two-thirds or more of Waukesha County was once beneath the Lake Michigan Lobe of the Wisconsin Glaciation. This is the lobe that crossed what is now the Wisconsin shoreline of Lake Michigan and the Michigan Basin to the east and reached into northern Indiana and Illinois. In Wisconsin, the cities of Sheboygan, Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and, further inland, Waukesha all rose on the outwash of the Lake Michigan Lobe. The Green Bay Lobe of the Wisconsin Glaciation flowed more southwestward from what is now Green Bay, crossed present-day Waukesha County from roughly the north central portion to the southwest corner, and continued only a short way beyond. Its terminal moraine, the elevated ridge of glacial debris marking its furthest progress, curves around to the west and up the central part of the state, looking on the map like the shaky outline of a chubby forefinger. In the eastern counties of Wisconsin the Ice Age Trail largely follows the line where the Green Bay and Michigan Lobes met, and from where they diverged, the trail follows the terminal moraine of the Green Bay Lobe. If we were to hike the trail’s entire thousand-plus miles, from Potawatomi State Park on the Door Peninsula to Interstate Park on the St. Croix River, we would pass near August Derleth’s Sac Prairie, Aldo Leopold’s shack, and John Muir’s boyhood lake. The more northern terminal moraines of other lobes that descended only a third of the way down the state—the Langlade, the Wisconsin Valley, the Chippewa, and the Superior—lead the trail the rest of the way to the border with Minnesota. South of those lobes a relatively narrow band of terrain shows evidence of earlier glaciation prior to the Wisconsin Glaciation, and south of that band is the large southwestern quarter of the state known as the Driftless Area, with no sign of glaciation. When you think of Wisconsin’s landscape, you think in terms of either the glacier’s presence or its absence.

The Ice Age Trail grew out of the desire to preserve evidence of the Wisconsin Glaciation and to encourage people to explore glacial features and learn about glacial geology by walking through the terrain it formed—in essence, to enhance people’s connection with their own home ground. The idea originated in the 1950s with Ray Zillmer, a Milwaukee lawyer and avid hiker. Zillmer’s advocacy of the Wisconsin Glacier National Forest Park led to legislation that eventually supported aspects of his concept. August Derleth was one of the prominent figures in Wisconsin who supported the idea.

Zillmer died in 1960 and didn’t see his idea come to fruition. But in 1964 the Ice Age National Scientific Reserve was established, as Henry Reuss, the Wisconsin congressman who authored legislation to create the reserve, points out in On the Trail of the Ice Age, to “assure protection, preservation, and interpretation of the nationally significant features of the Wisconsin glaciation, including moraines, eskers, kames, kettle holes, swamps, lakes, and other reminders of the Ice Age.” By 1973, nine units around the state, consisting of state parks, recreation areas, and forest and wildlife preserves, had been created to protect glacial landscapes and landforms, and the reserve was officially dedicated. Zillmer’s dream had been a thousand-mile-long national park; the Ice Age Reserve was hardly that, since its separate locations were scattered across the state. But the reserve sites were located in places along the line formed by the limits of the Wisconsin ice sheet’s final advance, places that would have been part of the Wisconsin Glacier National Forest Park; the idea of linking them by means of a thousand-mile trail arose readily. Eventually, through the work of volunteers, enough progress had been made on the trail that in 1980 Congress renamed the IAT the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, giving it equal status with the Appalachian and Pacific Crest National Scenic Trails, under the aegis of the National Park Service. In the thirty-five years since then, almost seven hundred of the proposed thousand-plus miles of the trail have been completed, some of them running through national and state forests and state and county parks, some of them running across private lands, all of them maintained by dedicated volunteers in twenty-one different IATA chapters scattered across thirty counties. More than 130 people have officially walked the entire length of the trail (compared with more than twelve thousand on the Appalachian Trail and nearly five thousand on the Pacific Crest Trail).

Sue and I likely will not be among those who complete the thousand miles, but we have been among those working and walking on the trail segments in Waukesha County. A phrase of Aldo Leopold’s sometimes comes to mind when I’m on the trail. In “Marshland Elegy” he described a dawn wind rolling a bank of fog across the marsh “like the white ghost of a glacier.” It seems to me that, when we and the others we sometimes work and hike with walk the Ice Age Trail, we’re walking with the white ghost of the glacier, the glacier forever out of sight, of course, but on the best hikes, still somehow companionably, impressively present.

In the Monches segment the Carl Schurz Forest is a definite woods on definitely glacial terrain, and the Oconomowoc River floodplain is more or less enclosed and self-contained. Despite occasional houses and yards at certain points along the trail, it was easy for us to concentrate on the landscape and the forces that shaped it, easy to develop a sense of where we were. The next few segments will give us little chance to feel the same kind of seclusion. It will be like moving abruptly from Muir’s Fountain Lake or Leopold’s shack to Derleth’s Sac Prairie, from a mostly natural setting to a mostly developed one.

On a January afternoon, walking from an ice-coated parking lot near the southern end of the Monches segment, we pass through the stone arch below the railroad trestle just as a freight train rumbles across overhead, as if to confirm the continued need for the overpass. At the nearby trailhead for the Merton segment we follow the trail up a steep slope into the woods, paralleling the Oconomowoc River in the distance for a way, then veering off and descending onto the bed of the defunct Kettle Moraine Railway. The tracks were laid down in the nineteenth century by the Milwaukee and Superior Railroad, which intended to cross the state to the Lake Superior ports of Superior and Duluth. But they only got as far as North Lake, four miles west of Merton, and for a while carried mostly gravel and ice to Milwaukee. The Kettle Moraine Railway, an old-timey tourist train running between North Lake and Merton, used the tracks more recently, until pressures from subdivision development, objecting to a loud, smoky historic locomotive blocking backroad traffic, forced the business to close. Rather than agricultural or vacation areas, Monches and Merton have become bedroom communities for commuters aspiring to a more suburban way of life.

To the west a fence closes off the wooden trestle over the Oconomowoc; to the east the rail bed is level and straight and walled in on either side by trees and higher ground. We follow the yellow-blazed Ice Age Trail path running along the southern slope parallel to the railway, as if it were more legitimate than the converted tracks, but when we near the top of the slope, we realize how narrow a strip of woodlands we’re walking through. The sunken bed of the railway makes the first stretch of this trail segment somewhat secluded, but we soon emerge onto the outskirts of Merton.

From here on we feel rather conspicuous following the trail in the open, sometimes on the rail bed, sometimes along a thin line of trees that makes us look incompetently furtive. We pass open farmland, a power station, the backs of houses and garages, on a flat, straight run to Dorn Road, the first of the off-trail connecting routes we’ll have to hike on the shoulder of the road, cars whizzing by in either lane. The road runs up and over a rise, and we descend to a bridge over the Bark River. We’ve crossed into the floodplain of a different river than the one we started near.

A throng of Canada geese floats on the surface of the river, backlit by late-afternoon sunlight and stretching off around the bend. There are too many to count, most of them barely moving. The trail almost immediately leads into the woods along the river and its wetlands. For a while, weaving near to and away from the river, seldom in sight of it, we continually agitate the geese. They can hear us clumping through mud and over stones and loudly comment on it. The stream is rimmed with ice and the eddies sometimes have a thin coating, but otherwise the water is clear and open. Eventually the trail winds away from the river, first into tall trees and then through dense thickets, and we no longer hear the geese. Wooded slopes rise in the distance on one side of us and on the other we often can’t see the sedges of the wetlands. In a little while we enter a broad meadow, brown grasses high on either side of the trail, and walk in sunshine along a glassy, ice-covered path. We emerge onto an open field heading toward a distant barn and a low roadside fence, where the river goes under another bridge. The river seems to widen here and flow serenely.

We’re nearly to the limit of the completed trail in the Merton segment. Across the road, after a short walk through some woods and over a bridge, we’ll enter a subdivision that takes us back to Dorn Road and a two-mile walk to the next trailhead. Connecting routes like this link completed segments of the Ice Age Trail. Sometimes they pass through quiet residential neighborhoods, sometimes along country roads, sometimes along crowded four-lane highways. The IATA continually negotiates for easements through more natural environments and continually works to complete new segments of the trail and to reroute older ones as development encroaches, but as yet it still needs the connecting routes.

Our walk in the Merton segment alters our sense of the Ice Age Trail from what the Monches segment implied it might be. Monches was entirely woods and riverbank, essentially a nature hike; Merton is largely the abandoned railway bed and passage through town and across and along roads, at best a rural walk. Only along that short stretch of the Bark River floodplain, where we saw sunlight gleaming off the breasts of the geese and listened to them murmuring about our passage, did we feel isolated enough to concentrate on our surroundings. We’re not eager to reach the subdivision and roadside connecting route and put it off for a month by heading back the way we’ve come.

In early February, sunshine and temperatures around forty degrees inspire an impromptu hike of the Hartland segment, the next section to the south, which also passes through glacial terraces of sand and gravel outwash. From the northern Hartland trailhead in Centennial Park, a paved path parallels the Bark River behind a heavy growth of slender trees on a narrow strip of riverbank. It makes me wish the trail from Merton had stayed close to the stretch of the river Milton J. Bates describes canoeing in The Bark River Chronicles.

In the nineteenth century, rivers were the sites of choice where villages sprang up, exploiting the water’s potential for dams, mills, and commercial transportation. But after highways and railroads and other shifts in local economies diminished the water’s advantages, communities turned their backs on the rivers, building away from them and using them as drainage for sewage and refuse. Reuben Gold Thwaites, canoeing the Wisconsin River in 1887, thought the Sauk City of August Derleth’s parents’ day “a shabby town” of “squalid back yards” where “slaughter-houses abut the stream.” It led Thwaites to muse about the differences among river towns: “Some of them present a neat front to the water thoroughfare, with flower-gardens and well-kept yards and street-ends, while others regard the river as a sewer and the banks as a common dumping ground, giving the traveler by boat a view of filth, disorder, and general unsightliness which is highly repulsive.” Only a downturn in manufacturing and a late-blooming recognition of the aesthetic appeal and commercial potential for tourism, recreation, and real estate of rivers inspired efforts to restore and even celebrate them. Such seems the case in Hartland. We pass many people out walking the paved paths along the river that the Ice Age Trail follows. Once again, in our hiking clothes we feel as conspicuous as voyageurs blundering into a civilized settlement.

From Centennial Park the river flows strongly through snow-lined banks and substantial cottonwoods. The trail soon arcs through a corridor of trees at the base of sloped lawns leading to a higher level of residences, sternly designated as private property. We clatter over a solid, well-built boardwalk, cross an arched wooden bridge, and walk another narrow corridor of trees above a flat, leaf-covered riverbank. At Hartbrook Drive, we face the raised embankment of State Highway 16 and detour through an underpass. The cars whooshing overhead sound more frenzied and determined than the train crossing the Oconomowoc over-pass. The trail heads away from roads to follow the Bark all the way to downtown Hartland. There we leave the river, rise onto the main business street, and begin an urban stroll, down village streets and over city bridges, into Nixon Park. Misinterpreting signs, we head south on Cottonwood Avenue and discover ourselves at the Hartland Ice Age Wetland, an extensive marsh along the Bark River.

Hundreds of geese congregate in open water deeper in the marsh, away from the road. The brown grasses and the blue water and the multitudes of geese replay the scene we admired at the end of our Merton hike, as if the geese had all floated downstream over the course of a month. The wetland stretches a long way off on either side of the road, occupying the lowlands created by a glacial spillway, overlooked by housing on the highlands above it. Across the river and across the road, in a little cleared space, a sign like the one for the Carl Schurz Forest commemorates John Wesley Powell. Four years older than John Muir, Powell grew up on a farm in Walworth County, just south of Waukesha County, and, like Muir, really made his mark in the American West. Powell’s exploration of the Colorado River was memorably epic, and his contributions as the head of the US Geological Survey were significant. His connection with Wisconsin marshland is tenuous, but as a Wisconsin-born conservationist Powell merits recognition, though the sign is easy to ignore by passing drivers on Cottonwood Avenue and a little challenging for hikers to reach.

In Hartland, the Ice Age Trail takes us by two other commemorative sites for Wisconsin conservationists. From the Powell site we backtrack a little through a residential area to get to the Aldo Leopold Overlook, above the eastern end of the marsh. At the top of a forty-five-foot glacial hill we find, appropriately enough, a Leopold bench with a view of the marsh. Below us is a frozen pond, with a couple of nesting boxes jutting up out of the ice. Beyond a stretch of tall sedges we see the geese crowded along the open water of the Bark. This is not the marshland that inspired Leopold’s “Marshland Elegy,” but it will do, and for a conservationist whose writing is intimately connected with the Wisconsin environment, it seems an inviting place to read that essay.

From the Leopold Overlook, the Ice Age Trail skirts the wet-lands on one side and housing developments on the other and rambles to the Hartland Marsh–John Muir Overlook. A sign at the top of a rise quotes Muir’s description of Fountain Lake and refers to this marsh as an Ice Age wetland. A footpath loops deeper into the area. Two years earlier, on our first hike with our IATA chapter, Sue and I took a tour through the marsh led by Paul Mozina, who had been laboring for years to remove invasive plants crowding out native growth. He’d burned six hundred piles of brush, mostly buckthorn, cleared the forest floor, and planted native flora. We saw red oak, white oak, bur oak, cottonwoods—some trees were magnificently huge—white wild geraniums. After long walks on boardwalks around the marsh we hiked to an old homestead, only a totem pole and a stone bench and fireplace still standing, and crossed the Bark River. We startled a great horned owl that flew off while we stood watching.

It was only much later that I began to link the Wisconsin Conservationists Hall of Fame signs for Schurz, Powell, Leopold, and Muir with Mozina’s work on the Hartland Marsh. The memorial signs for those historic ecologists are meant to be affirmative and perhaps inspiring, a link between the volunteers who serve as stewards and work crews for the Ice Age Trail and the pioneering figures who advocated for the land. But in their out-of-the-way locations, they testify to the tangential presence in the public mind of the people they commemorate; those commemorative overlooks would be easy to bypass for anyone not following the blazes for the Ice Age Trail. But almost anywhere on the completed and conscientiously maintained sections of the Ice Age Trail—off the connecting routes and on the trail itself—or here in the restored areas of Hartland Marsh, a person would be at once aware that some contemporary volunteers share the spirit, the passion, of those earlier figures and perhaps sense that their connection to their home ground is deep and thoughtful and strong.

I felt hints of that on our first Ice Age Trail outing, not only in Hartland Marsh, but also in a section of woods that Sue and I now routinely hike as IAT stewards. South of the Muir Overlook, through an open corridor between commercial buildings and residential areas and across a busy road and near more housing, the trail enters an open field, where summer grasses grow higher than hikers’ heads, and arcs through it to dense woods. It wanders west along a slope, some farmland visible on the lowland to the north, a tony residential neighborhood out of sight beyond the top of the rise. For the most part this stretch is secluded and closed in, with huge oaks standing along the trail. The trail here essentially crosses the till settled on the western edge of the Niagara Escarpment, which underlies the upland to the east of the trail through Hartland, most notably just east of the Leopold Overlook, and much of the Kettle Moraine from this point on. The escarpment isn’t exposed here, but on our first hike through this section—the one that took us to Hartland Marsh—I was aware of its submerged presence and liked sensing it. At some places on the trail I’m more attuned to the gray ghost of the escarpment than to the white ghost of the glacier.

Trail stewards help maintain the trail by walking their sections often, picking up trash and debris, hacking back obstructions, removing fallen limbs or trees. I’ve come to this section on chapter workdays when volunteers rerouted the trail around an eroded slope, unblocked a flooding stream, yanked out buckthorn and garlic mustard, leveled the tread. Ice Age Trail volunteers share a sense of responsibility not only for the condition of the trail but also for heightening the connection hikers or casual walkers might feel for the terrain they pass through. Like the Monches segment or that stretch of the Bark River in Merton or the wetlands in Hartland, this one-mile stretch of woods lifts me out of time and immerses me in the moment, in my sense of where I am.

That feeling of connection dissipates quickly when I leave this stretch of woods. The trail winds past huge houses and vast lawns, passes behind a huge church, and follows the edge of a golf course to a junction with the Lake Country Recreation Trail, a paved bike trail it shares through the city of Delafield.

We return in March to the junction of the Hartland and Delafield segments, at a busy intersection on State Highway 83. On the ups and downs of the Delafield trail segment, we’re too aware of walking a paved path under towering power lines to concentrate on the terrain. We walk amidst an abundance of other walkers and bikers. Soon we descend onto the streets of Delafield, pass historic buildings like the 1846 Hawks Inn and a busy, bustling downtown, and stride out along the bike path until the Ice Age Trail separates from it. The Delafield segment is essentially an urban stroll through an appealing-enough town, if you enjoy taking a stroll through a town. All along the way I’m reminded of my wanderings—and August Derleth’s—in Prairie du Sac and Sauk City and I suspect that only someone with Derleth’s expansive sense of home ground, his feeling for both town and terrain, will connect to this segment in the way he connected to Sac Prairie. By the time we’re climbing away from the Lake Country Recreation Trail toward the trailhead for the Lapham Peak segment, I realize that at almost no point in the day have I thought about the glacier that formed the terrain all this disguises.

At the intersection of Highway 83 and Golf Road, where the Hartland and Delafield segments meet, a drugstore occupies one corner, a shopping plaza another, and a park-and-ride lot a third, while multiple lanes of traffic rush in between. The highway slopes down toward exit and entrance ramps for Interstate 94, which spans the bottom of the slope, then rises up the other side of the valley toward more shopping centers. Within a half-mile stretch there are five traffic lights. For his course on Waukesha County’s glacial geology at the University of Wisconsin– Waukesha, Marlin Johnson took his class, me among them, to a parking lot near a coffee shop on the southern slope and asked us to survey this congested area and imagine everything on it gone. A pleasant idea, if difficult to achieve. Johnson was explaining the complications of land formation here, the way the glacier would have dammed the nearby lakes—Nagawicka to the west, Pewaukee to the east—in different places at different times and forced meltwater to find different routes away from the basins. One ancient river channel that resulted was likely formed by a catastrophic collapse of an ice dam that sent a massive amount of meltwater scouring the landscape to the south and coming to rest in the lowest areas it could find. Later, when we drove south on Highway 83, we could see the floodplain of peaceful, placid Scuppernong Creek, the quiet inheritor of that wide, flat channel; and on Highway 18, when we parked at one of the southern access points for the Lapham Peak section of the IAT, we noted the flatness of the land to the east and the wooded rise of the land to the west. For those few minutes at least, we seemed to be connected to the ghost of a glacier.

The challenge for anyone trying to comprehend glacial geology is imagining the scale of past events in light of the physical world you stand on while you search for it. Marlin Johnson’s class and my efforts to walk this portion of my home ground are centered on one relatively small area affected by the Wisconsin glaciation, one county out of more than fifty that were covered by the ice, and one of seven counties on the dividing line between the Lake Michigan and Green Bay Lobes.

The Kettle Moraine, which dominates the remainder of the Ice Age Trail across the rest of Waukesha County, extends to the north through Washington and Ozaukee Counties and south through a corner of Jefferson County into Walworth County. The Niagara Escarpment, which underlies much of the Kettle Moraine in Waukesha County and is usually credited with dividing the Lake Michigan and Green Bay Lobes, reaches northeast to the end of Wisconsin beyond the Door Peninsula, arches through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and down the Bruce Peninsula of Ontario, heads east to form Niagara Falls, and crosses western New York state. Fifty counties, 120 miles of Kettle Moraine, nearly 1,000 miles of Niagara Escarpment, glacial deposition dating back 16,000 to 22,200 years—this is what I mean by scale.

And then there’s the matter of how complicated it can be to explain events that took place over millennia, and how difficult it is, first, to unravel what evidence still exists and, second, to compose an explanation comprehensible to a layperson—say, to a person like me. Glaciers advanced and melted back and advanced again, and streams ran below and through them and around their edges, and what formed at one time got altered at a later time and that got altered still later in a way that exposed a portion of what was there before the earlier alteration. And so on.

Meltwater stream sediment ran across open surfaces, but ice buried beneath the open surfaces could be covered by till; when that ice melted, the sediment could sink and form kettle depressions and turn the sediment around the kettles into “hummocky” hills and ridges. Lee Clayton, in Pleistocene Geology of Waukesha County, Wisconsin, tells us, “The Kettle Moraine consists of a nested series of partly collapsed outwash fans and eskers, overlain by till in places, and formed at the apex of the angle between the Green Bay and Lake Michigan Lobes.” Outwash fans are the sediment deposited by meltwater at the glacier’s edge; eskers are the meandering ridges formed from the sediment in streams flowing within the glacier; till is the debris on top of the glacier that settles when the ice melts. I find it bewildering to try to sort out the sequence of any of those things happening.

You say a term like “kettle moraine” and, because you have an idea what a “kettle” is and an idea what a “moraine” is—and may even be able to explain the differences among “lateral,” “terminal,” “recessional,” and “medial” moraines—you have a single uniform image in your head. That kettles here might sometimes be “kettles” (formed by the settling of debris on melting blocks of ice) and sometimes be simple depressions on either side of a hummock (it’s the buildup of the hummocks that creates the depressions); that “moraine” here might not be an accurate geological term (Clayton claims “the Kettle Moraine is more nearly an esker than a moraine”); that marked differences in terrain exist along the length of the Kettle Moraine—all these tend to fracture that uniform image.

Mickelson notes that, throughout the Kettle Moraine, very little till can be found and “nearly all the sediment is sand or a combination of sand and gravel that was deposited by meltwater.” For that reason, Mickelson argues, “the Kettle Moraine is not a moraine by most definitions but instead is an interlobate zone where supraglacial and subglacial streams deposited sand and gravel.” Somehow, “supraglacial and subglacial interlobate deposit zone” doesn’t have quite the ring to it that “Kettle Moraine” does, but Mickelson’s description is a good one to keep in mind when you’re trying to figure out what you’re traveling through on these segments of the Ice Age Trail.

“The Kettle Moraine has no borders,” Laurie Allman asserts, in Far from Tame: Reflections from the Heart of a Continent. “There is no precise moment when one can be said to pass into or out of it.” Instead, she says, it “runs in a snaking and discontinuous line.”

When preservation of the Kettle Moraine as a geological feature of the Wisconsin landscape was first proposed, it was envisioned as an unbroken state forest, something that, like the Ice Age Trail, one might walk through from end to end without ever leaving, but the state was unable and often unwilling to push for that vision. The Kettle Moraine State Forest today consists of a large Northern Unit, a large Southern Unit, and three small units in between, Pike Lake, Loew Lake, and Lapham Peak. The separation of the units has been made permanent by the development of communities around and in between them. The Ice Age Trail passes through every unit, and Mickelson and his coauthors divide its path through the Kettle Moraine into northern, middle, and southern sections. In Waukesha County the Monches, Merton, Hartland, and Delafield segments are assigned to the Middle Kettle Moraine, and the Lapham Peak, Waterville, Scuppernong, Eagle, and Stony Ridge segments to the southern Kettle Moraine.

From the southern end of the Delafield segment on, Sue and I will be hiking in terrain somewhat more familiar to us. All the Kettle Moraine State Forest units have other trails in addition to the Ice Age Trail, some for summer hiking and winter skiing, some for mountain biking, some for horseback riding, and we’ve walked such trails in Lapham Peak and the Southern Unit. Often, in our early hikes, the trail we followed would cross the Ice Age Trail and we would wonder what it was and why it was different from any of the color-coded loops we were walking. Now we’ll be crossing those other trails and adding a disoriented feeling of familiarity to the sense of discovery the Ice Age Trail often provides. We’ll also have to broaden our viewpoint. From here on we’ll have to take in not only the Ice Age Trail but the Kettle Moraine as well.

On the second weekend in March, on a gorgeous, sunny day with temperatures in the low sixties, we hike the Lapham Peak segment of the Ice Age Trail. Its northern trailhead occupies a corner of a vast, open, grassy area atop a steep rise a hundred feet higher than the surface of a small lake half a mile west. The trail wanders across rolling terrain beneath a uniform field of brown grasses and a pale blue sky, passes an isolated parcel of oak trees, and crosses toward more extensive woods on a slope to the east.

Laurie Allman, who wandered the area in November, observed that “with the leaves mostly down it is easier to see the contours of the land that make the region a showcase for the work of the last ice age.” Until the foliage thickens, we’ll find that statement true.

We wind our way up into a stretch of woods with an under-growth-free floor and a sense of spaciousness. From a ridge we spot an observation tower in the distance, rising above Lapham Peak itself. Back again in the grasses we pass preserved savanna, century-old white oaks, and restored prairie, all of it still winter dormant but full of wildflower promise for the warmer seasons. Our meandering course makes the grassland seem more extensive and broad than it is, almost as if we’re walking across presettlement prairie early settlers would recognize. The trail turns east and eventually dips toward wetlands, the hummocky shallows still ice-coated in places but the ponds open water. On one large pond two geese float serenely. Memories of the landscape surrounding Muir’s Fountain Lake flash across my mind. A long, tilting boardwalk takes us across the wetlands around the pond, and then we enter the forested stretch of the Lapham Peak segment.

The trail is level here, circling a large pond fringed with cattails and marshland and a viewing platform jutting out on one side. We angle back into the trees, the forest floor open and the trees relatively young and widely spaced, and climb the western slope of Lapham Peak. Soon the trees give way and our view of the wooden tower opens up. It’s forty-five feet high, rising above the leafless oaks that surround it. The tower and the trees stand starkly against the empty blue of the sky, above the scruffy brown grasses.

We’ve been up the tower before. On one of our earliest outings in Wisconsin, we wanted to stand on the highest point in Waukesha County and compare its 1,233 feet of elevation with the 14,000-foot elevations of the peaks we’d climbed a few months before in Colorado. The difference in vistas was obvious, of course, and Lapham Peak couldn’t inspire anything like the awe that Longs Peak had. It took me a while to realize that it didn’t have to. Now I have a richer sense of where I am and what I should be looking for; namely, the distinguishing features that identify my home ground—the drumlins formed by the Lake Michigan Lobe visible to the east toward Waukesha, the drumlins formed by the Green Bay Lobe to the west, the flat bed of Glacial Lake Scuppernong to the southwest. The “peak” itself is a glacial hill, and roughly twenty miles off to the north, if the day is particularly clear, it’s possible to see the basilica on the top of Holy Hill, a moulin kame in Washington County a hundred feet higher than Lapham Peak. (A “moulin” is a vertical shaft in a glacier through which debris spills to form a conical hill, or “kame.”) With binoculars I can usually locate the basilica’s towers, even through midafternoon haze, but picking out the drumlins is more challenging now that so much of the terrain is tree-covered—I rely on occasional farmlands to make their shapes more visible. It’s hard to imagine away the visible evidence of the twenty-first century when we stand at the top of the Lapham Peak tower, but if we try we might be able to glean a sense of our glacial origins.

I was drawn to Lapham Peak, even before I knew about the Ice Age Trail, because of Increase Allen Lapham, one of the most fascinating figures in early Wisconsin history. He had a relentless curiosity and a wide-ranging intelligence, and his accomplishments are impressive in their breadth and scope. Considering what he contributed to botany, geology, zoology, history, archaeology, engineering, surveying, education, conservation, and meteorology—I hope I haven’t overlooked any area of his interests—it’s startling to realize that he was essentially self-taught in all those fields.

I also feel a personal connection, though in reality there is none. Lapham was born in Palmyra, New York, in 1811, the son of a canal contractor. At the age of thirteen he was employed cutting stone for the locks of the Erie Barge Canal in Lockport, New York. That’s where my personal connection comes in—and reveals its remoteness: Lockport is the town where my parents met and married and where I was born, none of which would have happened if locks hadn’t been constructed at that section of the canal.

Lapham’s experience with canals brought him to Milwaukee in 1836, just before Wisconsin Territory separated from Michigan. He’d been hired as the chief engineer on the Milwaukee and Rock River Canal, intended to skirt lake traffic around Chicago to the Mississippi. The canal plan fell through but Lapham stayed on, married, and settled in Milwaukee. For nearly forty years he was active in the social and cultural life of Wisconsin: the Milwaukee Female Seminary (which later grew into the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee), Carroll College (now University) in Waukesha, the Wisconsin Academy of Science, Arts and Letters, the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, the Young Men’s Society (whose book collection grew into the Milwaukee Public Library), the Milwaukee Public High School, the Natural History Society, and the Milwaukee Public Museum—all these are indebted to his energy and intellect. For a man with no formal schooling—his doctorate from Amherst College in 1860 was honorary—he seems to have had great zeal for learning and for opening doors to knowledge for others.

Lapham’s publications were varied and essential. In 1836, the year he arrived, he published the first scientific pamphlet in Wisconsin, A Catalogue of Plants and Shells Found in the Vicinity of Milwaukee on the West Side of Lake Michigan. In 1844 he published A Geographical and Topographical Description of Wisconsin, the first book about the territory, later titled in the second edition, Wisconsin: Its Geography and Topography, History, Geology, and Mineralogy; Together with Brief Sketches of Its Antiquities, Natural History, Soil, Productions, Population, and Government. It was widely distributed and is credited with spurring emigration to the territory. As early as 1836, as deputy surveyor for the new Wisconsin Territory, he surveyed effigy and burial mounds throughout the region, and in 1855 the Smithsonian Institution published The Antiquities of Wisconsin as Surveyed and Described, Lapham’s thorough review of the existing earthworks he had encountered and recorded. Worried about the potential “loss of those records of an ancient people,” he argued, “Now is the time, when the country is yet new, to take the necessary measures for their preservation.” In the end Lapham’s book served as a catalog of what would be destroyed by cultivation and settlement in the century and a half since the book was published. To me, what Lapham’s Antiquities still records is its author’s powers of rational speculation and, even more strongly, his powers of foresight, both found throughout his writings.

In 1867 Lapham, J. G. Knapp, and H. Crocker published their Report on the Disastrous Effect of the Destruction of Forest Trees, Now Going On So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin. The epigraph for the report comes from Man and Nature by George Perkins Marsh: “Man has too long forgotten that the earth was given to him for usufruct alone, not for consumption, still less for profligate waste.” Lapham and his coauthors warned that removing the forests would have a detrimental impact on the environment, making summers hotter, winters colder, winds stronger, ground dryer, springs and rivers more likely to dry up, floods more extensive, “the soil on sloping hills washed away; loose sands blown over the country preventing cultivation; . . . the productiveness of the soil diminished”; and thunderstorms, hail, and rains more frequent and more intense. I don’t know to what extent the ecological history of Wisconsin since their report confirms the accuracy of these predictions, but certainly Aldo Leopold’s account of the sand county farm he first occupied bears witness to some of the effects they forecast. The report also foreshadows the Dust Bowl and perhaps our own era of climate change and harks back to the history of the Muirs’ Fountain Lake Farm. It perhaps confirms a tendency in people to concentrate on the promise of immediate rewards rather than on the potential for eventual catastrophe.

Lapham was a thorough record keeper. This thoroughness extended to his observations about the weather. According to Martha Bergland and Paul G. Hayes, in Studying Wisconsin: The Life of Increase Lapham, soon after Lapham’s arrival in Milwaukee he began “calculating the length and severity of Wisconsin winters by recording the dates each year when the Milwaukee River froze over and thawed.” He installed his instruments on the west shore of the river, “little more than a block east of the Lapham home,” and recorded temperatures, barometric pressures, snow and rain fall totals, and high and low water levels of both Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River. When Lapham was away from home, his wife and sons continued to add to his records.

The results of this methodical recordkeeping, like Aldo Leopold’s phenological records on his sand county surroundings, led Lapham to speculate on the practical possibilities of weather observation. In 1850 he unsuccessfully urged the Wisconsin legislature to establish a state weather bureau. But twenty years later, in 1870, Congress approved Lapham’s proposal, thereby establishing the National Weather Bureau. The United States Army Signal Corps created a system of twenty-four observer network stations. Signals sent from Pikes Peak in Colorado were received by telegraph at the station on Government Hill in Wisconsin and relayed to headquarters in Chicago. Lapham wired the first published national weather forecast on November 8, 1870, reporting high winds in Cheyenne and Omaha and predicting, “Barometer falling and thermometer rising at Chicago, Toledo, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Rochester. High winds probable along the lakes.” A marker commemorating this first national weather forecast was erected at Lapham Peak in 1955, and I stop to read it every time I visit the tower. And each time I hear the radio telling me the National Weather Service station in Sullivan has issued some warning or other—Sullivan is a little farther west of Lapham Peak—I think of Increase Lapham and what he accomplished.

In 1875 Lapham died of a heart attack in a rowboat on Oconomowoc Lake, in northwest Waukesha County, shortly after he’d completed writing his final scientific paper, “Oconomowoc and Other Small Lakes of Wisconsin Considered in Reference to Their Capacity for Fish Production.” After nearly four decades in Wisconsin, he apparently never tired of learning about the state and passing on what he learned. I admire that about Increase Lapham. He certainly merits being commemorated as a conservationist along with Muir, Leopold, Schurz, and Powell, not simply with a sign but with a state park. Like Muir, Leopold, and Derleth, he reminds me that, wherever we are, there is always something more to learn about what we make our home ground.

And so I try to pay attention as the Ice Age Trail descends a long, steep set of stairs on the east side of the tower hill. The woods close in around us, thicker and denser than on the western slope. We trudge a long way through deep woods, the path often narrow, continually rising and falling, bending and turning; we can seldom see far ahead or far behind or very deep into the trees and shrubbery on either side. Occasionally we cross a few of the other, wider park trails used for winter snowshoeing and skiing and I strain to recognize them as ones we’ve been on before. At times we notice kettles below us off the trail, a few of them dry, many of them still ice covered, a blur of white at the bottom of brown, leaf-coated slopes. Near the eastern boundary of the park we begin to meander south, reaching ever-lower elevations until we move out of the close packed trees and onto a terrace above a flat floodplain, with good views of wetlands further east. We pass through an open meadow, with an occasional sprawling bur oak that stops me in my tracks from admiration. I wonder from their size if any are older than Leopold’s Good Oak.

We soon reach the trailhead on US 18, where Marlin Johnson took his glacial geology class to view the south end of that glacial meltwater channel. Scuppernong Creek flows through the channel now, a spring-fed “underfit stream” too small to have originally cut it. I think about the Scuppernong Creek floodplain on one side of Lapham Peak, the restored prairie, oak opening, and savanna on the other side, the tower on the hilltop, and the flourishing forest we’ve wound our way through, and I realize that being able to hold it all in my mind means I’m getting closer to being at home in it.

One thing I don’t keep in mind often enough is the difference between the Kettle Moraine as a geological feature and the Kettle Moraine State Forest as an official natural resource. Established in 1937, the state forest, in all its units, has distinct borders, but the geological entity, as Laurie Allman observed, hasn’t. When I leave the Kettle Moraine State Forest I’m still in the Kettle Moraine itself. In the same way, though it’s handy to break the Ice Age Trail into identifiable sections with distinct trailheads to mark beginnings and endings—handy, that is, for those who prefer to hike the forty-five miles in Waukesha County or the thousand-plus miles in Wisconsin in short spurts rather than in one continuous march—the Ice Age terrain the trail traces is vaster than its outline in our hiking atlas. When someone writing about New Jersey or New England mentions the extent of the Wisconsin Glaciation there, I’m grateful for the reminder: the Wisconsin Glaciation wasn’t just for Wisconsin. If I grant myself a moon’s-eye view of the northern hemisphere more than a hundred centuries ago, I gain a richer perspective on what the trail we walk is connected to.

Here and now, of course, my perspective is most often narrowly focused on the ground where I place my hiking shoes, and my peripheral vision extends no farther than the edges of the trail. Even so, as I follow the Ice Age Trail through both the geological and the governmental Kettle Moraines, I continually encounter cues that send me across time, in connections both tenuous and temporal.

The temporal comes in flashes of memory from places we’ve hiked before. In our first year in Wisconsin, looking for nearby hiking trails, we were drawn first to Lapham Peak and then to trails in the Southern Unit of the Kettle Moraine State Forest. The John Muir Trail in northern Walworth County, popular with mountain bikers in dry, warm weather, introduced us to the forests, ridges, and kettles of the Kettle Moraine. We took it in March, when the leaves were down, the contours exposed, and the trail too muddy or intermittently snowy and icy for bikers. Other than the trickiness of the footing, I remember most vividly the view from high on a narrow ridge into a leatherleaf bog at the bottom of a large kettle and reveled in the seclusion along the trail.

The trail had originally been intended by the Sierra Club to be mostly undeveloped. The former Kettle Moraine trails coordinator Ray Hajewski explains, in Candice Gaukel Andrews’s Beyond the Trees, that it was meant to be “a walk through the wild woods. If a tree fell down across the trail, so be it. You’d walk over it or around it.” At first, it could be imagined as a trail someone like John Muir would want to walk; but over time, to accommodate cross-country skiers and mountain bikers, all the trails in the southern Kettle Moraine State Forest were widened and rerouted, and their crowded use sorely altered the terrain. Some careful redesigning has since ameliorated some of the damage, but as any hiker who has walked a trail shared with bikers knows, the pleasure of a walk in the woods is ferociously detonated by the headlong rush of a mountain biker hurtling a rise or exploding out of a curve—bikers usually ride the woods for speed and challenge, not for solitude and serenity. Once the ground dried out and the snow evaporated, we avoided most loops on the John Muir Trail.

A year later we hiked the Emma Carlin Trail in southeastern Jefferson County, again too early for bikers, and we were entirely alone on the trail. We started out from a glacial sand plain and walked through hardwood forests to a vista over Lower Spring Lake and a potential sighting of distant Holy Hill, but I didn’t appreciate sufficiently what we were seeing or realize that, because the Ice Age Trail skirts both the John Muir Trail and the Emma Carlin Trail, I had learned where the trail and the Kettle Moraine both go when they leave Waukesha County.

My interest in knowing where I was grew slowly. Closer to home in Waukesha County, I hiked the Scuppernong Trail a couple of weeks after we’d been on the Muir, and I still recall the impact the terrain there had on me. If you think that brown and gray are two colors that ought to dominate a landscape, the view on every side was a study in their use. Walking alone, meeting no one else, all I heard was the wind rustling dead leaves on the bare trees and my own feet shuffling through leaves on the trail, which often skittered around me in the wind. Sometimes sand was underfoot, sometimes gravel, but mostly leaves and, under towering pines, thick layers of pine needles.

Often the trail would climb a ridge alongside a deep bowl, sometimes one on either side, and I would wonder about the glacial forces that had been at work there. When I got home I reread Laurie Allman’s chapter on the Kettle Moraine and looked in Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape for definitions of moraine, drumlin, esker, kame, outwash plain, and kettle (I was delighted to learn that Walden Pond is a kettle). I made sure I brought Sue with me back to the Scuppernong Trail, crossing the Ice Age Trail with only a little curiosity and unaware that Scuppernong is the northernmost IAT segment in the southern Kettle Moraine State Forest.

The more tenuous connections grew out of my discovery that, in the IAT’s Waterville segment, between the Lapham Peak and Scuppernong segments, and in the Eagle segment, just south of the Scuppernong, it would be possible to see outcroppings of the Niagara Escarpment if I walked the Ice Age Trail.

I was born on the Niagara Escarpment. It’s the geological feature that the Erie Barge Canal had to climb using the same locks Increase Lapham helped build in Lockport. I’ve driven often along the escarpment in Southern Ontario, hiked some of it on Ontario’s Bruce Peninsula, run into it inadvertently on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and vacationed on it on Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula. The Niagara Escarpment is the geologic feature I relate to most, a feature that begins not far from where I did and ends (more or less, by not surfacing again beyond it) here in Waukesha County, where I likely will.

The escarpment is some four hundred million years older than the last Ice Age. To simply say the name transports me at once back to the Silurian Period, in the middle of the Paleozoic Era, and simultaneously back to the mid-twentieth century and a view of the Lockport locks. It’s an inevitable and irresistible act of time travel.

Sometimes, similar though less intense moments happen as a result of having taken that glacial geology class. We took a field trip around Waukesha County, stopping on Highway 18 to gaze at a very clear example of a drumlin, following the glacial channel from its source at Nagawicka and Pewaukee Lakes down the floodplain of Scuppernong Creek to the end of the Lapham Peak unit, and wandering a portion of the Scuppernong Springs Nature Trail in the Kettle Moraine State Forest. At Scuppernong Springs, where Paul Mozina, our guide at Hartland Marsh, leads an effort to restore the marshland and return the Scuppernong River to its original channel, we saw evidence of multiple eras of time. The marsh there once was mined for marl, the chalky, lime-rich deposit laid down in glacial lakes and excavated to use as fertilizer and mortar—the same substance that lines the bottom of Muir’s Fountain Lake. In addition to that early-twentieth-century enterprise, at varying times there were a nineteenth-century trout hatchery, a hotel, a sawmill, a cranberry bog, and eventually a brewery on the site. A Native American encampment preceded all of them. Scuppernong Springs is presently on its way back to its presettlement state, but to walk it is to intersect with half a dozen time periods in ways that may not be so obvious in other places.

As I wrestle with that moon’s-eye view, zooming in and zooming out as on a satellite map, I try to remember that I should also attempt to see things at various moments in an immense timeline, even if it means also trying to somehow see the invisible and the vanished.

On the summer day we set off from the northern Waterville trail-head, after a short walk through woods and along a meadow, we have to trudge for more than a mile along the shoulder of Waterville Road to get back onto the trail. Then we’re in woods, soon taking a long solid boardwalk through lowlands, passing under tall trees and through thick undergrowth. The forest seems broad and high. We’re just off the western side of the Kettle Moraine, angling along terrain on its Green Bay Lobe side and following the edge of the Niagara Escarpment, crossing rolling terrain with some steep slopes. It’s quiet in the woods and I often gawk at the older, larger oaks, until I sprawl headlong on the trail from not watching my feet. When I stand up, Sue points at a deer running away from us, no doubt alarmed by the whoomp of my fall. When we cross a subdivision street where I parked a few years before and enter the longer, more secluded stretch of the segment, I start recalling moments from that earlier hike.

On that autumn day I passed through what my hiking guide described as “remnants of pre-settlement vegetation: oak forest, oak openings, prairie and wetland” looking for “a small exposed section of native dolomite bedrock,” part of the Niagara Escarpment. It was a short hike, generally downhill, through forest almost all the way. Generally the forest floor was closed with undergrowth, though occasionally the darkness from the canopy kept it clear of growth but dense with fallen trunks and limbs. I constantly tramped over acorns and oak leaves. At one point the trail wound its way along the edge of a field and then took a turn that brought me into the open. A large hayfield spread out before me, newly mown, with scattered wheels of hay standing here and there. Three sandhill cranes idled in the middle distance, moving with that stately slow-motion strut, occasionally lowering their heads to the ground. This was one of my first crane sightings in Wisconsin, and I gazed at them for several minutes. Eventually one of them complained about my standing there and, rather than prompt them to flight, I moved on.

The trail went lower and crossed some wetlands and another field, and when I could hear cars on the road again, I assumed I wasn’t far from the southern trailhead and turned around. On the way back I noticed the outcroppings of buried dolomite under my feet and located some off to the side of the trail, but I found no especially pronounced formation. Except for the cranes, a few other birds invisible in the foliage, and the occasional squirrel, I’d seen no signs of wildlife; occasionally I heard distant voices from nearby farms or the sound of machinery but only near the end of the hike did I meet a man in a bright yellow vest, pumping walking sticks, coming the other way. Otherwise I’d been on the trail for an hour and a half alone.

Now, walking the Waterville segment again, I look for familiar places.

Soon enough we top a rise and parallel the edge of the spacious hayfield where I saw the cranes my first time through; it’s empty now, but I can’t help scouring the field in hopes of spotting them. After a few minutes of fruitless gazing, we keep walking. As we descend steeply, wind through more woods and out along a grassy and uncultivated field, cross low wetlands on some rather unstable puncheons, and make the slight rise up to the southern trailhead on a county road, I keep thinking about the cranes I saw almost three years earlier, when cranes were not so familiar to me; images from Leopold’s “Marshland Elegy” arise as well. There’s a long chain of connection between the birds and the land, and my awareness of it makes me less disturbed than I once might have been by the abrupt appearance of a hayfield in the midst of my woodland walk.

On that earlier fall hike the Niagara dolomite was harder to spot, covered in moss and leaf litter. This time through I notice more rocks exposed on the trail, their color and shape familiar to me now from other escarpment sites I’ve visited. I like the idea that the ground I’m walking on here is an extension of the home ground I walked all through my childhood.

The connecting route between the Waterville and Scuppernong segments is the last one in the county. From the northern Scuppernong trailhead on we’ll be in the Kettle Moraine State Forest all the way to the county line. On a cool June day we start out between two pastures, one fallow, the other filled with stunted stalks of corn and vast rectangles of hay. The trail is straight and flat until we enter the woods where the land rises and angle south on a continuous upslope. These are ice-contact slopes, gravel deposits once lower than the surrounding ice but, once the ice was gone, now higher than the surface the ice rested on. The climb takes us onto a mostly level area along a red pine plantation and into the sprawling Pinewoods campground. From now on we expect to cross wider, more open trails that we’ve followed on other hikes. The Ice Age Trail is narrow and runs through ground cover, with alternating stands of red pine and oak overhead, though at one point we pass a stretch of low white pine. A couple of orange signs with large black letters advise: “Don’t Shoot This Direction ↑ Houses Ahead.” We wonder how close the areas open to seasonal hunting are. The only people we see in this section of the Scuppernong are a woman and two teenaged girls, each with a large, aggressive dog on a leash, following one of the broader hiking trails. The dogs pull on their restraints and lean in our direction, but the women yank them back and keep talking without overtly noticing us. Until now we’ve seemed to have the woods to ourselves.

We are enclosed in green, the trail a narrow corridor through underbrush, sunlight dappling it through a high, thick canopy. The high point of the trail is at 1,066 feet and the trail soon becomes a series of ups and downs, elevations changing between 50 and 100 feet. The southern trailhead will be 200 feet lower than that high point. We gain a ground-level appreciation of what the geology guide means by the term “high-relief hummocky topography.” We continually climb and descend, at one moment on top of a slope, at the next winding through a densely overgrown gully or swale bottom. The forest undergrowth is generally so thick that it’s hard to see very far into it, but I’m continually aware of slopes falling steeply off on either side of us or, in the low sections, rising high in all directions.

The ground beneath our feet keeps changing, sandy at times in the lower regions, packed mud in other low sections, flat needle-covered sections under the pines, and on the slopes unsorted or undifferentiated rocky till. I recognize plenty of oaks as well as pines, and other hardwoods, such as maple and hickory and probably basswood, black cherry, and aspen. At times we find ourselves passing among towering red pines, sometimes in a seemingly endless plantation, other times down a mostly clear narrow corridor beneath them, the trail largely carpeted with pine needles. On a winding turn in the trail we find a middle-aged man in an Iowa Hawkeyes T-shirt and a baseball cap, standing off to the side, reviewing scenes he’s shot on a large digital camera. He glances up at us, smiling, and says, “This isn’t a forest preserve—this is the forest.” I smile back at him. He has it right. For a good long time now we’ve had no inkling of where the forest might end or what might be beyond it. I keep the thought in mind as we continue down the trail.

In the course of its route across Wisconsin, particularly in the northwest section of the state, the Ice Age Trail passes through rugged terrain, where forests are deep and broad and chances of encountering black bears and at least hearing timber wolves are not unlikely and backpacking is the only way to get from one trailhead to another. In those sections it’s possible to truly feel as if you’re walking the wilderness. At times on the Lapham Peak and Scuppernong trail segments I had a similar feeling of immersion, of being intimately connected to the landscape, as if I were only one more of its standard elements. It’s a feeling I prize, as if for a little while I have surrendered connection to the inorganic, manufactured world and merged my essence with the organic, natural world. It’s a very temporary, ephemeral feeling. I welcome it when it comes and I’m sorry but not surprised how quickly it passes.

But I have no illusions about the wildness or naturalness of the Waukesha portions of the Ice Age Trail. The very trail itself is a constructed thing, and as local members of the Ice Age Trail Alliance, Sue and I have been on volunteer work crews rerouting and maintaining portions of the trail we’ve trod on as hikers. In the state natural areas and the state forest, long-term projects have focused on clearing away invasive plants, restoring native growth, conducting controlled burns, and building boardwalks and bridges. Almost anywhere we’re likely to see prairies and wetlands and oak savannas that resemble those of presettlement years, we’re seeing restoration successes at the hands of dedicated volunteers who have removed the impact of almost two centuries of cultivation and development to bring those places back to what they were. And, though the Ice Age Trail often avoids them, historical reminders of the uses to which the land has been put remain sprinkled nearby throughout the Kettle Moraine—remnants of the marl plant, rail bed, trout hatchery, and hotel at Scuppernong Springs, remnants of the spring house, bottling plant, turbine dam, trout pond, and hotel at Paradise Springs, at least three log cabins and one homestead site—and all those contemporary recreational areas—campgrounds, hiking, biking, and skiing trails, horse and snowmobile trails, a winter sports center, dog trial grounds, three Ice Age Trail backpacking shelters. There are times when you can imagine what the country was like when it was a string of farms, when it was dotted with commercial enterprises, when what we pass through now wasn’t here.

In the natural order of things, terrain changes all the time, often in infinitesimal transformations invisible at the moments they occur and perhaps over unimaginable stretches of time; or sometimes in tumultuous alterations—the bursting of an ice dam, the gushing of floodwaters, inundation at one time, depletion and draining at another. Although human beings for centuries had an impact on the Wisconsin landscape through prairie fires and agriculture and burial and effigy mounds and the wearing of paths into the earth, after the influx of European American settlers in the mid-nineteenth century, change more often was radical, extreme, and myopic, impelled by short-term goals that had long-term consequences for the land.

Everywhere we walk along the Ice Age Trail in Waukesha County we are walking through terrain that human beings have changed, sometimes in dire and damaging ways, sometimes in restorative healing ways, sometimes in ways that valued personal goals over an appreciation of land as a part of a biotic community, as something more than a commodity. The gulf between community and commodity is likely unbridgeable.

Still, among all those homeowners who have built with an eye to a vista, all those walkers and joggers who make paths from their own backyards onto the trails in parks and forests, all those who choose to locate their neighborhoods near woods and wetlands and rivers, many must be people who feel connected to their home ground, who value it, who don’t want it to change.

Muir, Leopold, and Derleth each dealt with change in their home ground—they had to deal with it by virtue of feeling a part of it. As tempting as it is for someone like me to desire a pristine, thoroughly natural setting for the Ice Age Trail, the very act of maintaining it the way we do assures that it can’t be pristine and natural. And it may be that in all the places the landforms of ten thousand years ago share space with the constructed elements of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, we have the opportunity to recognize how transient our constructions are, especially when measured against the endurance of the country we’re passing through.

By the end of June, we’re in the midst of a drought and the mosquitoes that usually plague summer hiking haven’t been around. We leave the northern trailhead of the Eagle segment on a balmy day bright with unobstructed sunshine. When we enter the trees, I recall walking through them a few years before, impressed by their height and breadth, immediately entranced by Wisconsin oaks. I point out certain trees to Sue. Some of the oaks here are more than a century old. Often the undergrowth is thick, but in places leaf fall keeps the forest floor open. At the moment the ground is dry, yet the long winding stretches of recently installed puncheons tell us the trail is usually muddy in the woods and in the low wetlands beyond.

The trail breaks out of the trees to cross a portion of the Kettle Moraine Low Prairie State Natural Area, filled with wet meadow plants like blue-joint grass, shrubby cinquefoil, valerian, grass of Parnassus, and Ohio goldenrod. We spot two bluebirds, a common yellowthroat, a chipping sparrow, some Henslow’s sparrows, a yellow warbler, and a bobolink. The trail takes us across a gravel road that leads to a dirt parking lot where we’d rendezvoused with a dozen other members of our chapter two months before for an IAT workday. That morning we rerouted a portion of the trail away from an imminent subdivision, established the tread on the new trail, pulled invasive plants like garlic mustard, and replaced blazes. Across the road we climb up a grassy knoll, arcing around a cluster of trees and high shrubs and past a side trail leading off to a Leopold bench and a scenic view north across the low prairie. At the top of the knoll another Leopold bench, more in the open, provides an even more expansive view.

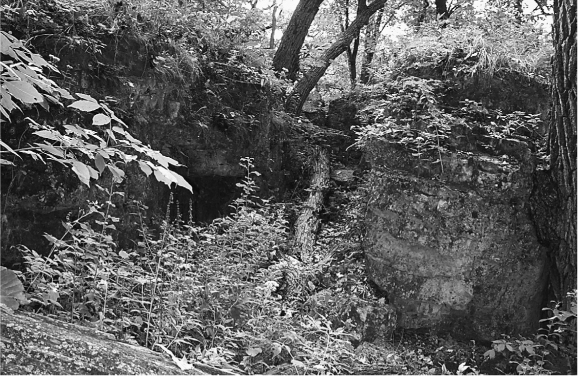

From that bench the trail veers west toward the woods, dips down to cross a creek on a solid bridge, then climbs to the section of the trail we rerouted on that workday. We try to stay alert to the changes in the landscape a couple months have wrought. The trail now curves more deeply into the woods, toward glimpses of the prairie, and then crosses a midslope section leading toward the Brady’s Rocks loop. Brady’s Rocks were what drew me to the Eagle segment the first time I came. As far as I knew they were the southernmost outcropping of the Niagara Escarpment in Wisconsin and the last visible sign of the arc that extends all the way back to my hometown. I set out to find them on a crisp fall day, on a side trail then more remote from the main Ice Age Trail. I found some blocks of stone visible on the ground, completely coated in thick coverings of moss, and soon reached an area where I was surrounded by the rocks.

Michael and Kathleen Brady were Irish immigrants who settled in the area in 1855 to farm and at some point quarried some of the Niagara dolomite on their property. Remnants of a stone fence and the escarpment outcropping itself are now all that remain. I moved slowly around the slope where the outcropping was visible. The light-colored underlayers seemed evenly laid down while the darker capstone layers, which bear the brunt of weathering, were bumpy and weathered and uneven. Crevices and ledges and shelves revealed how much more erodible the lower layers were, how resistant the top layers. I thought of how Niagara Falls retreats upriver, the soft underside of the dolomite wearing away support for the resistant rock above, until it breaks off from its own weight and plummets into the debris at the base of the falls. The same principle is at work here, though hardly on such a dramatic scale.

In the interval since my first visit there, the main trail was rerouted to make Brady’s Rocks less remote, and the path looping through the rocks was cleared to make the rocks more readily accessible. Today we walk the cool, shady loop slowly, the outcroppings often higher than our heads and surrounded by under-growth. We look closely at the greenery atop the rocks, hoping to identify three unique types of ferns found here: walking fern, fragile fern, and cliff brake. Walking fern, named for its tendency to grow a new fern where the tips of the old one touch the ground, is the fern for which Brady’s Rocks are best known.

Beyond Brady’s Rocks and back on the trail, the terrain levels out as we move through another stretch of the Kettle Moraine Low Prairie, this section lower, wet-mesic and dry-mesic intermingled. We walk in the open, in sunshine with an infrequent but welcome breeze, aware that in the past this part of the segment was agriculturally hard-used. Eventually we find ourselves back in a narrow shady corridor of trees. A boardwalk takes us across marshy wetland, where I’d once startled a smooth green snake that startled me; he surprised me again when I learned he actually is called “smooth green snake.” We pass through an extensive pine plantation, the trees too regularly spaced to be a natural grove.

When we come out of the last of the woods, we can see a long way to the west, across a panorama of grassland, the most extensive we’ve seen so far. We’re looking across the Scuppernong River Habitat Area. Its boundaries include the Scuppernong Prairie Natural Area, as well as the Kettle Moraine Low Prairie Natural Area, but the whole of the habitat area is much larger than the sum of those parts. For over a decade and a half the State Department of Natural Resources has been attempting to restore the prairie through controlled burns and brush cutting, and the area has the chance to become, at 3,500 acres, the largest low prairie east of the Mississippi. Even if we know it’s only a remnant of an area tens of thousands of acres broad, it’s pretty impressive to gaze upon and walk through, and its combination of sedge meadows, low prairies, fens, and tamarack swamps reminds me of the landscape John Muir entered as a child.