CHAPTER FIVE

THE HORSE ON THE SEA BED

The warm, transparent sea lay tranquil with scarcely a movement of its amazingly bright green-blue waves. Darr Veter went in slowly until the water reached his neck and spread his arms widely in an effort to keep his footing on the sloping sea bed. As he looked over the barely perceptible ripples towards the dazzling distant expanses he again felt that he was dissolving in the sea, that he was becoming part of that boundless element. He had brought his long suppressed sorrow with him, to the sea — the sorrow of his parting from the entrancing majesty of the Cosmos, from the boundless ocean of knowledge and thought, from the terrific concentration of every day of his life as Director of the Outer Stations. His existence had become quite different. His growing love for Veda Kong relieved days of unaccustomed labour and the sorrowful liberty of thought experienced by his superbly trained brain. He had plunged into historical investigations with the enthusiasm of a disciple. The river of time, reflected in his thoughts, helped him withstand the change in his life. He was grateful to Veda Kong for having, with the sympathy and understanding so typical of her, arranged the flying platform trips to parts of the world that had been transformed by man’s efforts. His own losses seemed petty when confronted with the magnificence of man’s labour on Earth and the greatness of the sea. Darr Veter had become reconciled to the irreparable, something that is always most difficult for a man.

A soft, almost childish voice called to him. He recognized Miyiko, waved his arms, lay on his back and waited for the girl. She rushed into the sea, big drops of water fell from her stiff, black hair and her yellowish body took on a greenish tinge under a thin coating of water. They swam side by side towards the sun, to an isolated desert island that formed a black mound about a thousand yards from the shore. In the Great Circle Era all children were brought up beside the sea and were good swimmers and Darr Veter, furthermore, possessed natural abilities. At first he swam slowly, afraid that Miyiko would grow tired, but the girl slipped along beside him easily and untroubled. Darr Veter increased his speed, surprised at her skill. Even when he exerted himself to the full she did not drop behind and her pretty immobile face remained as calm as ever. They could soon hear the dull splash of water on the seaward side of the islet. Darr Veter turned on to his back, the girl swam past him, described a circle and returned to him.

‘‘Miyiko, you’re a marvellous swimmer!” he exclaimed in admiration; he filled his lungs with air and checked his breathing.

“My swimming isn’t as good as my diving,” the girl replied, and Darr Veter was again astonished.

“I am Japanese by descent,” she explained. “Long ago there was a whole tribe of our people all of whose women were divers; they dived for pearls and gathered edible seaweed. This trade was passed on from generation to generation and in the course of thousands of years it developed into a wonderful art. Quite by accident it is manifested in me today, when there is no longer a separate Japanese people, language or country.”

“I never suspected….”

“That a distant descendant of women divers would become an historian? In our tribe we had a legend. There was once a Japanese artist by the name of Yanagihara Eigoro.”

“Eigoro? Isn’t that your name?”

“Yes, it is rare in our days, when people are named any combination of sounds that pleases the ear. Of course, everybody tries to find combinations from the languages of their ancestors. If I’m not mistaken your name consists of roots from the Russian language, doesn’t it?”

“They aren’t roots but whole words, Darr meaning ‘gift’ and Veter meaning ‘wind’.”

“I don’t know what my name means. But there really ‘ was an artist of that name. One of my ancestors found a picture of his in some repository. It is a big canvas, you can take a look at it in my house, it will be interesting for an historian. A stern and courageous life is depicted with extreme vividness, all the poverty and unpretentiousness of a nation in the clutches of a cruel regime!

Shall we swim farther?”

“Wait a minute, Miyiko. What about the women divers?”

“The artist fell in love with a diver and settled amongst that tribe for the rest of his life. His daughters, too, became divers who spent their lives at their trade in the sea. Look at that peculiar islet over there, it’s like a round tank, or a low tower, like those they make sugar in.”

“Sugar!” snorted Darr Veter, involuntarily. “When I was a boy these desert islands fascinated me. They stand alone, surrounded by the sea, their dark cliffs or clumps of trees hide mysterious secrets, you could meet with everything imaginable on them, anything you dreamed of.”

Miyiko’s jolly laugh was his reward. The girl, usually so reticent and always a little sad, had now changed beyond recognition. She sped on merrily and bravely towards the heavily breaking waves and was still a mystery to Veter, a closed door, so different from lucid Veda whose fearlessness was more magnificent trustfulness than real persistence.

Between the big offshore rocks the sea formed deep galleries into which the sun penetrated to the very bottom. These galleries, on whose bed lay dark mounds of sponges and whose walls were festooned with seaweed, led to the dark, unfathomed depths on the eastern side of the island. Veter was sorry that he had not taken an accurate chart of the coastline from Veda. The rafts of the maritime expedition gleamed in the sun at their moorings on the western spit several miles from their island. Opposite them was an excellent beach and Veda was there now with all her party; accumulators were being changed in the machines and the expedition had a day-off. Veter had succumbed to the childish pleasure of exploring uninhabited islands.

A grim andesite cliff hung over the swimmers; there were fresh fractures where a recent earthquake had brought down the more eroded part of the coast. There was a very steep slope on the side of the open sea. Miyiko and Veter swam for a long time in the dark water along the eastern side of the island before they found a flat stone ledge on to which Veter hoisted Miyiko who then pulled him up.

The startled sea birds darted back and forth and the crash of the waves, transmitted by the rocks, made the andesite mass tremble. There was nothing on the islet but bare stone and a few tough bushes, not a sign anywhere of man or beast.

The swimmers made their way to the top of the islet, looked at the waves breaking below and returned to the coast. A bitter aroma came from the bushes growing in the crevices. Darr Veter stretched himself out on a warm stone, and gazed lazily into the water on the southern side of the ledge.

Miyiko was squatting at the very edge of the cliff trying to get a better view of something far down below. At this point there were no coastal shallows or piled-up rocks. The steep cliff hung over dark, oily water. The sunshine produced a glittering band along the edge of the cliff, and down below, where the cliff diverted the sunlight vertically into the water, the level sea bed of light-coloured sand was just visible.

‘“What can you see there, Miyiko?” The girl was deep in thought and did not turn round immediately.

“Nothing much. You’re attracted to desert islands and I to the sea bed. It seems to me that you can always find something interesting on the sea bed, make discoveries.”

“Then why are you working in the steppes?”

“There’s a reason for it. The sea gives me so much pleasure that I cannot stay with it all the time. You cannot always be listening to your favourite music and it is the same with me and the sea. Being away for a time makes every meeting with the sea more precious.”

Darr Veter nodded his agreement.

“Shall we dive down there?” he asked, pointing to a gleam of white in the depths. In her astonishment Miyiko raised brows that already had a natural slant.

“D’you think you can? It must be about twenty-five metres deep there, it takes an experienced diver.”

“I’ll try. And you?”

Instead of answering him Miyiko got up, looked round until she found a suitable big stone which she took to the edge of the cliff.

“Let me try first. I’ll go down with a stone although it’s against my rules, but the floor is very clean, I’m afraid there may be a current lower down,”

The girl raised her arms, bent forward, straightened up and then bent backwards. Darr Veter watched her at her breathing exercises, trying to memorize them. Miyiko did not say another word but, after a few more exercises, seized hold of the stone and dived into the dark water.

Darr Veter felt a vague anxiety when more than a minute passed and the bold girl did not reappear. He, too, began looking for a stone, assuming that he would need one much bigger. He had just taken hold of an eighty-pound lump of andesite when Miyiko came to the surface. The girl was breathing heavily and seemed fatigued. “There,” she gasped, “there’s a horse.” “What? What horse?”

‘‘A huge statue of a horse, down there, in a natural niche. I’m going back to take a proper look.”

‘‘Miyiko, it’s too difficult for you. Let’s swim bade to the beach and get diving gear and a boat.”

‘‘Oh, no. I want to look at it myself, now! Then it will be my own achievement, not something done by a machine. We’ll call the others afterwards.”

“All right, I’m coining with you!” Darr Veter seized his big stone and the girl laughed.

“Take a smaller one, that one will do. And what about your breathing?”

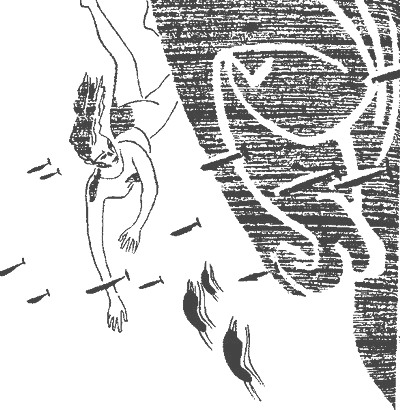

Darr Veter obediently performed the necessary exercises and then dived into the water with the stone in his hands. The water struck him in the face and turned him with his back to Miyiko; something was squeezing his chest and there was a dull pain in his ears. He clenched his teeth, strained every muscle in his body to fight against pain. The pleasant light of day was rapidly lost as he entered the cold grey gloom of the depths. The cold, hostile power of the deep water momentarily overpowered him, his head was in a whirl, there was a stinging pain in his eyes. Suddenly Miyiko’s firm hand seized him by the shoulder and his feet touched the firm, dully silver sand. With difficulty he turned his head in the direction she indicated; he staggered, dropped the stone in his surprise and shot immediately upwards. He did not remember how he got to the surface, he could see nothing but a red mist and his breathing was spasmodic. In a short time the effects of the high pressure wore off and that which he had seen was reborn in his memory. He had seen the picture for an instant only but his eye had seen and his brain recorded many details.

The dark cliffs formed a lofty lancet arch under which stood the gigantic statue of a horse. Neither seaweed nor barnacles marred the polished surface of the carving.

The unknown sculptor had endeavoured mainly to depict strength. The fore part of the body was exaggerated, the tremendous chest given abnormal width and the neck sharply curved. The near foreleg was raised so that the rounded knee-cap was thrust straight at the viewer while the massive hoof almost touched the breast. The other three legs were strained in an effort to lift the animal from the ground giving the impression that the giant horse was hanging over the viewer to crush him with its fabulous strength. The mane on the arched neck was depicted as a toothed ridge, the jowl almost touched the breast and there was ominous malice in eyes that looked out from under the lowered brow and in the stone monster’s pressed-back ears.

Miyiko was soon satisfied that Darr Veter was unharmed, left him stretched out on a flat stone slab and dived once again into the water. At last the girl had worn herself out with her deep diving and had seen enough of her treasure. She sat down beside Veter and did not speak until her breathing had again become normal.

“I wonder how old that statue can be?” Miyiko asked herself thoughtfully.

Darr Veter shrugged his shoulders and then suddenly remembered the most astonishing thing about the horse.

‘“Why is there no seaweed or barnacles on the statue?”

Miyiko turned swiftly towards him.

“Oh, I’ve seen such things before. They were covered with some special lacquer that does not permit living things to attach themselves to it. That means that the statue must belong approximately to the Fission Age.”

A swimmer appeared in the sea between the shore and the island. As he drew near he half rose out of the water and waved to them. Darr Veter recognized the broad shoulders and gleaming dark skin of Mven Mass. The tall black figure was soon ensconced on the stones and a good-natured smile spread over the face of the new Director of the Outer Stations. He bowed swiftly to little Miyiko and with an expansive gesture greeted Darr Veter.

“Renn Bose and I have come here for one day to ask your advice.”

“Who is Renn Bose?”

“A physicist from the Academy of the Bounds of Knowledge.”

“I think I’ve heard of him, he works on space-field relationship problems, doesn’t he? Where did you leave him?”

‘“On shore. He doesn’t swim, not as well as you, anyway.”

A faint splash interrupted Mven Mass. “I’m going to the beach, to Veda,” Miyiko called out to them from the water. Darr Veter smiled tenderly at the girl.

“She’s going back with a discovery,” he explained to Mven Mass and told him about the finding of the submarine horse. The African listened but showed no interest. His long fingers were fidgeting and fumbling at his chin. In the gaze he fixed on Darr Veter the latter read anxiety and hope.

“Is there anything serious worrying you? If so, why put it off?”

Mven Mass was not loath to accept the invitation. Seated on the edge of a cliff over the watery depths that bid the mysterious horse he spoke of his vexatious waverings. His meeting with Renn Bose had been no accident. The vision of the beautiful world known as Epsilon Tucanae had never left him. Ever since that night he had dreamed of approaching this wonderful world, of overcoming, in some way, the great space separating him from it, of doing something so that the time required to send a message there and receive an answer would not be six hundred years, a period much greater than a man’s lifetime. He dreamed of experiencing at first hand the heartbeat of that wonderful life that was so much like our own, of stretching out his hand across the gulf of the Cosmos to our brothers in space. Mven Mass concentrated his efforts on putting himself abreast of unsolved problems and unfinished experiments that had been going on for thousands of years for the purpose of understanding space I as a function of matter. He thought of the problem Veda Kong had dreamed of on the night of her first broadcast to the Great Circle.

In the Academy of the Bounds of Knowledge Renn Bose, a young specialist in mathematical physics, was in charge of these researches. His meeting with Mven Mass and their subsequent friendship was determined by a similarity of endeavour.

Renn Bose was by that time of the opinion that the problem had been advanced sufficiently to permit of an experiment, but it was one that could not be done at laboratory level, like everything else Cosmic in scale. The colossal nature of the problem made a colossal experiment necessary. Renn Bose had come to the conclusion that the experiment should be carried out through the outer stations with the employment of all terrestrial power resources, including the Q-energy station in the Antarctic.

A sense of danger came to Darr Veter when he looked into Mven’s burning eyes and at his quivering nostrils.

“Do you want to know what I should do?” He asked this decisive question calmly.

Mven Mass nodded and passed his tongue over his dry lips.

“I should not make the experiment,” said Darr Veter, carefully stressing every word and paying no attention to the grimace of pain that flashed across the African’s face so swiftly that a less observant man would not have noticed it.

“That’s what I expected!” Mven Mass burst out. “Then why did you consider my advice to have any importance?”

“I thought we should be able to convince you.” “All right, then, try! We’ll swim back to the others.

They’re probably getting diving apparatus ready to examine the horse!”

Veda was singing and two other women’s voices were accompanying her.

When she noticed the swimmers she beckoned to them, motioning with the fingers of her open hand like a child. The singing stopped. Darr Veter recognized one of the women as Evda Nahl, although this was the first time he had seen her without her white doctor’s smock. Her tall, pliant figure stood out amongst the others on account of her white, still untanned skin. The famous woman psychiatrist had apparently been busy and had not had time for sunbathing. Evda’s blue-black hair, divided into two by a dead straight parting, was drawn up high above her temples. High cheek-bones over slightly hollow cheeks served to stress the length of her piercing black eyes. Her face bore an elusive resemblance to an ancient Egyptian sphinx, the one that in very ancient days stood at the desert’s edge beside the pyramid tombs of the kings of the world’s oldest state. The deserts have been irrigated for many centuries, the sands are dotted with groves of rustling fruit-trees and the sphinx itself still stands there under a transparent plastic shade that does not hide the hollows of its time-eaten face.

Darr Veter recalled that Evda Nahl’s genealogy went back to the ancient Peruvians or Chileans. He greeted her in the manner of the ancient sun worshippers of South America.

“It has done you good to work with the historians,” said Evda, “thank Veda for that.” Darr Veter hurriedly turned to his friend Veda, but she took him by the hand and led him to a woman with whom he was not acquainted.

“This is Chara Nandi! All of us here are guests of hera and Cart Sann’s, the artist, you know they have been living on this coast for a month already. They have a portable studio at the other end of the bay.”

Darr Veter held out his hand to the young woman who looked at him with huge blue eyes. For a moment his breath was taken away, there was something about the woman that distinguished her from all others, something that was not mere beauty. She was standing between Veda Kong and Evda Nahl whose natural beauty was refined, as it were, by exceptional intellect and the discipline of lengthy research work but which nevertheless faded before the extraordinary power of the beautiful that emanated from this woman who was a stranger to him.

“Your name has some sort of resemblance to mine,” began Darr Veter.

The corners of her tiny mouth quivered as she suppressed a smile.

“Just as you yourself are like me!”

Darr Veter looked over the top of the mass of thick, slightly wavy black hair that came level with his shoulder and smiled expansively at Veda.

“Veter, you don’t know how to pay compliments to the ladies,” said Veda, coyly holding her head on one side.

“Does one have to know that deception is no longer needed?”

“One does,” Evda Nahl put in, “and the need for it will never die out!”

“I’d be glad if you’d explain what you mean,” said Darr Veter, knitting his brows.

“In a month from now I shall be giving the autumn lecture at the Academy of Sorrow and Joy, and it will contain a lot about spontaneous emotions, but in the meantime…” Evda nodded to Mven Mass who was approaching them.

The African, as usual, was walking noiselessly and with measured tread. Darr Veter noticed that the tan on Chara’s cheeks became tinged with pink as though the sun that had permeated her body were bursting out through her tanned skin. Mven Mass bowed indifferently.

“I’ll bring Renn Bose here, he’s sitting over there on a rock.”

“We’ll all go to him,” suggested Veda, “and on the way we’ll meet Miyiko. She’s gone for the diving apparatus. Chara Nandi, are you coming with us?”

The girl shook her head.

“Here comes my master. The sun has gone down and work will soon begin.”

“Posing must be hard work,” said Veda, “it’s a real deed of valour! I couldn’t.”

“I thought I couldn’t do it, either. But if the artist’s idea attracts you, you enter into the creative work. You seek an incarnation of the image in your own body, there are thousands of shades in every movement, in every curve! You have to catch them like musical notes before they fly away.”

“Chara, you’re a real find for an artist!”

“A find!” A deep bass voice interrupted Veda. “And if you only knew how I found her! It’s unbelievable!”

Artist Cart Sann raised a big fist high in the air and shook it. His straw-coloured hair was tousled by the wind, his weather-beaten face was brick-red and his strong hairy legs sank into the sand a though they were growing there.

“Come along with us, if you have time,” asked Veda, ‘‘and tell us the story.”

‘“I’m not much of a story-teller. But still, it’s an amusing tale. I’m interested in reconstructions, especially in the reconstruction of various racial types such as existed in ancient days, right up to the Era of Disunity. After my picture Daughter of Gondwana met with such success I was burning with ambition to reincarnate another racial type. The beauty of the human body is the best expression of race after generations of clean, healthy life. Every race tin the past had its detailed formulas, its canons of beauty I that had been evolved in days of savagery. That is the way we, the artists, understand it, we who are considered to be lagging behind in the storm of the heights of culture. Artists always did think that way, probably from the days of the palaeolithic cave painter. But I’m getting off the track…. I had planned another picture, Daughter of Thetis, of the Mediterranean, that is. It struck me that the myths of ancient Greece, Crete, Mesopotamia, America, Polynesia, all told of gods coming out of the sea. What could be more wonderful than the Hellenic myth of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. The very name, Aphrodite Anadiomene, the Foam-Born, she who rose from the sea…. A goddess, born of foam and conceived by the light of the stars in the nocturnal sea — what people ever invented a legend more poetic….”

“From starlight and sea-foam,” Veda heard Chara whisper. She cast a side glance at the girl. Her strong profile, like a carving from wood or stone, was like that of some woman of an ancient race. The small, straight, slightly rounded nose, her somewhat sloping forehead, her strong chin and, most important of all, the great distance from the nose to the high ear — all these features typical of the Mediterranean peoples at the time of antiquity were reflected in Chara’s face.

Unobtrusively Veda examined her from head to foot and thought that everything in her was just a little “too much.” Her skin was too smooth, her waist too narrow, her hips too wide. And she held herself too straight so that her firm bosom became too prominent. Perhaps that was what the artist wanted, strongly defined lines?

A stone ridge crossed their path and Veda had to correct the impression she had only just received: Chara Nandi jumped from boulder to boulder with an unusual agility, as though she were dancing.

“She must have Indian blood in her,” decided Veda. “I’ll ask her later on.”

“My work on the Daughter of Thetis,” the artist continued, “brought me closer to the sea, I had to get a feeling for the sea since my Maid of Crete, like Aphrodite, would arise from the waves and in such a manner that everybody would understand it. When I was preparing to paint the Daughter of Gondwana I spent three years at a forestry station in Equatorial Africa. When that picture was finished I took a job as mechanic on a hydroplane carrying mail around the Atlantic — you know, to all those fisheries and albumin and salt works afloat on big metal rafts in the ocean.

“One evening I was driving along in the Central Atlantic somewhere to the west of the Azores where the northern current and the counter-current meet. There are always big waves there, rollers that come one after another. My hydroplane rose and fell, one moment almost touching the low clouds and next minute diving deep into the trough between the rollers. The screw raced as it came out of the water. I was standing on the high bridge beside the helmsman. And suddenly… I’ll never forget it!

“Imagine a wave higher than any of the others that raced towards us. On the crest of this giant wave, right under the low ceiling of rosy-pearl clouds stood a girl, sunburned to the colour of bronze. The wave rolled noiselessly on and she rode it, infinitely proud in her isolation in the midst of that boundless ocean. My boat was swept upwards and we passed the girl who waved us a friendly greeting. Then I could see that she was standing on a surf board fitted with an electric motor and accumulator.”

“I know the sort,” agreed Darr Veter, “it’s intended for riding the waves.”

“What amazed me most of all was her complete solitude — there was nothing but low clouds, an ocean empty for hundreds of miles around, the evening twilight and the girl carried along on the crest of a giant wave. That girl….”

“Was Chara Nandi,” said Evda Nahl. “That’s obvious, but where did she come from?”

“She was not born of starlight and foam!” chuckled Chara, and her laughter had a surprisingly high, resonant note to it, “merely from the raft of an albumin factory. We were moored on the fringe of the Sargasso Sea where we were cultivating Chlorella[16] and where I was working as a biologist.”

“Be that as it may,” said Cart Sann, “but from that moment for me you were a daughter of the Mediterranean, born of foam. You were fated to be the model for my future picture. I had been waiting a whole year.” “May we come and look at it?” asked Veda Kong. “Please do, but not during working hours. You had better come in the evening. I work very slowly and cannot tolerate anybody’s presence when I am painting.” “Do you use colours?”

“Our work has changed very little during the thousands of years that people have painted pictures. The laws of optics and the human eye have remained the same. We have become more receptive to certain tones, new chromokatoptric colours[17]” with internal reflexions contained in the paint layer have been invented, there are a few new methods of harmonizing colours, that’s all; on the whole the artist of antiquity worked in very much the same way as I do today. In some respects he did better. He had confidence and patience — we’ve become more dashing and less confident of ourselves. At times strict nalvete is better for art. But I’m digressing again! It’s time for us to go. Come along, Chara!”

They all stood still and watched the artist and his model as they walked away.

“Now I know who he is,” murmured Veda, “I’ve seen the Daughter of Gondwana.”

“So have I,” said Evda Nahl and Mven Mass together.

“Gondwana, is that from the land of the Goods in India?” asked Darr Veter.

“No, it is the collective name for the southern continents. In general it is the land of the ancient black race.”

“And what is this Daughter of the Black People like?”

“It is a simple picture. There is a plateau, the fire of blinding sunlight, the fringe of a formidable tropical forest and in the foreground, a black-skinned girl, walking alone. One half of her face and her firm, tangibly hard, cast-metal body is drenched with blazing sunlight, the other half of her is in deep, transparent half-shadow. A necklace of white animal’s teeth hangs from her neck, her short hair is gathered at the crown of her head and covered with a wreath of fiery red blossoms. Her right arm is raised over her head to push aside the last branches of a tree that bar her way, with her left hand she is pushing a thorny stalk away from her knee. In the halted movement, in the free breathing, and in the strong sweep of the arm there is carefree youth, young life merging with nature into a single whole that is as change able as a river in flood…. This oneness is to be understood as knowledge, the intuitive understanding of the world. In her dark eyes, gazing over a sea of bluish grass towards the faintly visible outlines of mountains, there is a clearly felt uneasiness, the expectation of great trials in the new, freshly discovered world!” Evda Nahl stopped.

“It isn’t exactly expectation, it is tormenting certainty. She feels the hard lot of the black people and tries to comprehend it,” added Veda Kong. “But how did Cart Sann manage to convey the idea? Perhaps it is in the raising of the thin eyebrows, the neck inclined slightly forward, the open, defenceless back of her head…. And those amazing eyes, filled with the dark wisdom of ancient nature…. The strangest thing of all is that you feel, at the same time, carefree, dancing strength and alarming knowledge.”

“It’s a pity I haven’t seen it,” said Darr Veter. “I must go to the Palace of History and take a look at it. I can imagine the colours but I can’t imagine the girl’s pose.”

“The pose?” Evda Nahl stopped, threw the towel from her shoulders, raised her right arm high over her head, leaned slightly backward and turned half facing Darr Veter. Her long leg was slightly raised as though making a short step and not completing it, her toes just touching the ground. Her supple body seemed to blossom forth. They all stood still in frank admiration.

“Evda, I could never have imagined you like that!” exclaimed Darr Veter, “you’re dangerous. You’re like the half exposed blade of a dagger!”

“Veter, those clumsy compliments again,” laughed Veda, “why half and not fully exposed?”

“He’s quite right,” smiled Evda Nahl, relaxing to her normal self, “not fully. Our new acquaintance, Chara Nandi, is a fully drawn and gleaming blade, to use the epic language of Darr Veter.”

“I can’t believe that anybody can compare with you!” came a hoarse voice from amongst the boulders. Only then did Evda Nahl notice the red hair cut ere brosee and the blue eyes that were gazing at her adoringly with a look such as she had never before seen on anybody’s face.

“I am Renn Bose!” said the red-headed man, bashfully, as his short, narrow-shouldered figure appeared from behind a boulder.

“We were looking for you,” said Veda, taking the physicist by the hand, “this is Darr Veter.”

Renn Bose blushed and the freckles on his face and neck stood out even more prominently than before.

“I stayed up there for some time,” said Renn Bose, pointing to a rocky slope. “There is an ancient tomb there.”

“It is the grave of a famous poet who lived a very long time ago,” announced Veda.

“There’s an inscription on the tomb, here it is.” The physicist unrolled a thin metal sheet with four rows of blue symbols on it.

“Those are European letters, symbols that were in use before the world linear alphabet was introduced. They had clumsy shapes that were inherited from the still older pictograms. But I know that language.”

“Then read it, Veda!”

“Be quiet for a few minutes!” she demanded and they all obediently sat down on the rocks. Very soon Veda stood before the seated people and read her improvised translation:

Thoughts and events and our dreams are all fleeting,

Vanquished by time like a ship lost at sea…

Leaving this world on my journey of journeys,

Earth’s dearest obsession I’m talting with me…

“That’s exquisite!” Evda Nahl rose to her knees. “A modern poet couldn’t have said anything better about the power of time. I should like to know which of Earth’s obsessions he thought the best and took with him in his last thoughts.”

“He no doubt thought of a beautiful woman,” said Renn Bose, impetuously gazing at Evda Nahl. Or did she imagine it?

A boat of transparent plastic containing two people appeared in the distance.

“Here comes Miyiko with Sherliss, one of our mechanics, he goes everywhere with her. Oh, no,” Veda corrected herself, “it’s Frith Don himself, the Director of the Maritime Expedition. Good-bye, Veter, you three will want to stay together so I’ll take Evda with me!”

The two women ran down to the gentle waves and swam together to the island. The boat turned towards them but Veda waved to them to go on. Renn Bose, standing motionless, watched the swimmers.

“Wake up, Renn, let’s get down to business!” Mven Mass called to him. The physicist smiled in shy confusion.

A stretch of firm sand between two ridges of rock was turned into a scientific auditorium. Renn Bose, using fragments of seashells, drew and wrote in the sand, in his excitement he fell flat, his body rubbing out what he had written and drawn so that he had to draw it all again. Mven Mass expressed his agreement or encouraged the physicist with abrupt exclamations. Darr Veter, resting his elbows on his knees, wiped away the perspiration that broke out on his forehead from the effort he was making to understand. At last the red-headed physicist stopped talking, and sat back on the sand breathing heavily.

“Yes, Renn Bose,” said Darr Veter after a lengthy pause, “you have made a discovery of outstanding importance.”

“I did not do it alone. The ancient mathematician Geiaenberg propounded the principle of indefiniteness, the impossibility of accurately defining the position of tiny particles. The impossible has become possible now that we understand mutual transitions, that is, we know the repagular calculus[18]. At about the same time scientists discovered the circular meson cloud in the atomic nucleus, that is, they came very near to an understanding of anti-gravitation.”

“We’ll accept that as true. I’m not a specialist in bipolar mathematics,” particularly the repagular calculus which studies the obstacles to transition. But I realize that your work with the shadow functions is new in principle, although we ordinary people cannot properly understand it unless we have mathematical clairvoyance. I can, however, conceive of the tremendous significance of the discovery. There is one thing…” Darr Veter hesitated.

“What, what is there?” asked Mven Mass, anxiously.

“How can we do it experimentally? I don’t think we can create a sufficiently powerful electromagnetic field….”

“To balance the gravitational field and obtain a state of transition?” inquired Renn Bose.

“Exactly. Beyond the limits of the system, space will remain outside our influence.”

“That’s true, but, as always in dialectics, we must look for a solution in the opposite. Suppose we obtain an anti-gravitational shadow vectorally and not discretely.”

“Ah! But how?”

Swiftly, Renn Bose drew three straight lines and a narrow sector with an arc of greater radius intersecting them.

“This was known before bipolar mathematics. Two thousand and five hundred years ago it was called the Problem of the Fourth Dimension. In those times there was a widespread conception of multidimensional space; the shadow properties of gravitation, however, were unknown and people attempted to find an analogy with electromagnetic fields which led them to believe that points of singularity meant that matter had disappeared or had been changed into something that could be named but could not be explained. How could they have had any conception of space with their limited knowledge of the nature of phenomena? But our ancestors could guess — you sec, they realized that if the distance from, say, star A to the centre of Earth along line OA is twenty quintillion kilometres, then the distance to the same star by vector OB will equal zero… in practice, not zero but approaching it. They said that zero time would be achieved if the velocity of motion were equal to the velocity of light. Remember that the cochlear calculus2” has been only recently discovered!”

“Spiral motion was known thousands of years ago,” Mven Mass remarked cautiously, interrupting the scientist. Kenn Bose dismissed the remark disdainfully.

“They knew the motion but not the laws! It’s like this, if the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field are two sides of one and the same property of matter and if space is a function of gravitation, then the function of the electromagnetic field is antispace. The transition from one to the other yields the vector shadow function, zero space, which is known in everyday language as the speed of light. I believe it to be possible to achieve zero space in any direction. Mven Mass wants to visit the planet of Epsilon Tucanae — it’s all the same to me as long as I can set up the experiment! As long as I can set up the experiment!” repeated the physicist, lowering his short white eyelashes wearily.

“You will need not only the outer stations and Earth’s energy, as Mven Mass pointed out, but some sort of an installation as well. Such an installation cannot be simple or easily erected.”

“In that respect we’re lucky. We can use Corr Yule’s installation near the Tibetan Observatory. Experiments for the investigation of space were carried out there a hundred and seventy years ago. There will have to be some adjustments and, as far as volunteers to help me are concerned, I can get five, ten, twenty thousand any time I like. I have only to call for them and they will take leave of absence and come.”

“You seem to have thought of everything. There is only one other consideration, but it is the most important — the danger of the experiment. There may be the most unexpected results; in conformity with the law of big numbers we cannot make a preliminary attempt on a small scale. We must take the extraterrestrial scale from the start.”

“What scientist would be afraid of risk?” asked Renn Bose, shrugging his shoulders.

“I wasn’t thinking of personal risk! I know that there will be thousands of volunteers as soon as they are required for some dangerous and novel enterprise. The experiment will also involve the outer stations, the observatories, the whole system of installations that has cost mankind a tremendous amount of labour. These are installations that have opened a window into the Cosmos, that have put mankind in contact with the life, knowledge and creative activity of other populated worlds. This window is mankind’s greatest achievement: do you think that you, or I, or any other individual or group of individuals has the right to take the risk of closing it, even for a short time? I would like to know whether you feel that you have that right and on what grounds?”

“I have and on good grounds,” said Mven Mass, rising to his feet. “You have been at archaeological excavations — do not the billions of unknown skeletons in unknown graves appeal to us? Do they not reproach us and make demands of us? I visualize billions of human lives that have passed, lives in which youth, beauty and the joy of life slipped away like sand through one’s fingers — they demand that we lay bare the great mystery of time, that we struggle against it! Victory over space is victory over time, that is why I’m sure that I’m right, that’s why I believe in the greatness of the proposed experiment!”

“My feelings are different,” said Renn Bose. “But they form the other side of the same thing. Space still cannot be overcome in the Cosmos, it keeps the worlds apart and prevents us from discovering planets with populations similar to ours, prevents us from joining them in one family that would be infinitely rich in its joy and strength. This would be the greatest transformation since the Era of World Unity, since the days when mankind finally put an end to the separate existence of the nations and merged into one, in this way making the greatest progress towards a new stage in the conquest of nature. Every new step in this direction is more important than anything else, more important than any other investigations or knowledge.”

Renn Bose had scarcely finished when Mven Mass spoke again.

“There is one other thing, a personal one. In my youth I had a collection of old historical novels. There was one story about your ancestors, Darr Veter. Some great conqueror, some fierce destroyer of human life of whom there were so many in the epochs of the lower forms of society, launched an attack against them. The story was about a strong youth who was madly in love. His girl was captured and taken away — ’driven off”“ was the word used in those days. Can you imagine it? Men and women were bound and driven off to the country of the conqueror like cattle. The youth was separated from his beloved by thousands of miles. The geography of Earth was unknown, riding and pack animals were the only means of transport. The world of those days was more mysterious and vast, more dangerous and difficult to cross than Cosmic space is for us today. The young hero hunted for his dream, for years he wandered terribly dangerous paths until he found her in the depths of the Asian mountains. It is difficult to define the impression I had when I was younger, but it still seems to me that I, too, could go through all the obstacles of the Cosmos to the one I loved!”

Darr Veter smiled wanly.

“I can understand your feelings but I cannot get clear for myself what logical grounds there are for comparing a Russian story to your urge to get into the Cosmos. I understand Renn Bose better. Of course, you warned us that this was personal….”

Darr Veter stopped. He sat silent so long that Mven Mass began to fidget.

“Now I understand why it was that people used to smoke, drink, bolster themselves up with drugs at moments of uncertainty, anxiety or loneliness. At this moment I feel just as alone and uncertain — I don’t know what to say to you. Who am I to forbid a great experiment? But then, how can I permit it? You must turn to the Council, then….”

“No, that won’t do.” Mven Mass stood up and his huge body was tensed as though he were in mortal danger. “Answer us: would you make the experiment? As Director of the Outer Stations, not as Renn Bose, he is different….”

‘No!” answered Darr Veter, firmly. “I should wait.”

“What for?”

“The erection of an experimental installation on the Moon;’

“And power for it?”

“The lesser gravity of the Moon and the smaller scale of the experiment will make only a few Q-stations necessary.”

“But that would take hundreds of years and I should never see it!”

“You wouldn’t, but as far as the human race is concerned it doesn’t matter whether it’s now or a generation later.”

“But it’s the end for me, the end of my dream! And for Renn….”

“To me it means that it’s impossible to check up my work experimentally and make corrections — it means I cannot continue!”

“One mind is not enough. Ask the Council.”

‘‘Your ideas and your words are the Council’s decision given in advance. We have nothing to expect from them,” said Mven Mass softly.

“You’re right. The Council will refuse.”

“I shan’t ask you anything else. I feel guilty, Renn and I have put the heavy burden of decision upon you.”

“That is my duty as one older in experience. It is not your fault that the task seems magnificent and extremely dangerous. That is what upsets me so much, makes it hard to bear.”

Renn Bose was the first to suggest returning to the temporary dwellings of the expedition. The three downcast men plodded through the sand, each in his own way feeling the bitter sorrow of having to reject an experiment such as had never before been tried. Darr Veter cast occasional side glances at his companions and felt that it was harder for him than for them. There was a bold recklessness in his nature that he had had to fight against all his life. It made him something like an old-time brigand — why had he felt such joy and satisfaction in his mischievous battle with the bull? In his heart he was indignant, he was full of protest against a decision that was wise but not bold.