Yet Coco grew restless during the summer and made her way back to Paris. The Nazis had occupied the city, but Hitler had decided not to destroy it. In August Coco returned to the Ritz and found that high-ranking German officers had taken over the hotel, including her grand suite. But the commandant allowed her to stay and gave her a small room. Coco carried on by avoiding the Nazis. She knew from surviving her difficult childhood how to make the best of a bad situation. German soldiers stood in line in front of the House of Chanel in the hope of being able to buy a bottle of perfume. “Idiots!” she sneered.

However, around this time she began dating a German intelligence officer, Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage, called Spatz (the Sparrow). Coco at age fifty-seven enjoyed the companionship of a charming younger man. She claimed she had met him before the war. Now Spatz visited her at her private apartment above the salon at rue Cambon. He wore civilian clothes, not a uniform, because he was a spy, a member of the Abwehr, the Nazi intelligence agency. He may even have been a double agent working for both the Nazis and the British. “He often came to see Mademoiselle at rue Cambon but we never saw him in uniform,” wrote Coco’s maid, Germaine Domenger, after the war in a letter defending Coco. Coco had been accused of collaborating with the Germans.

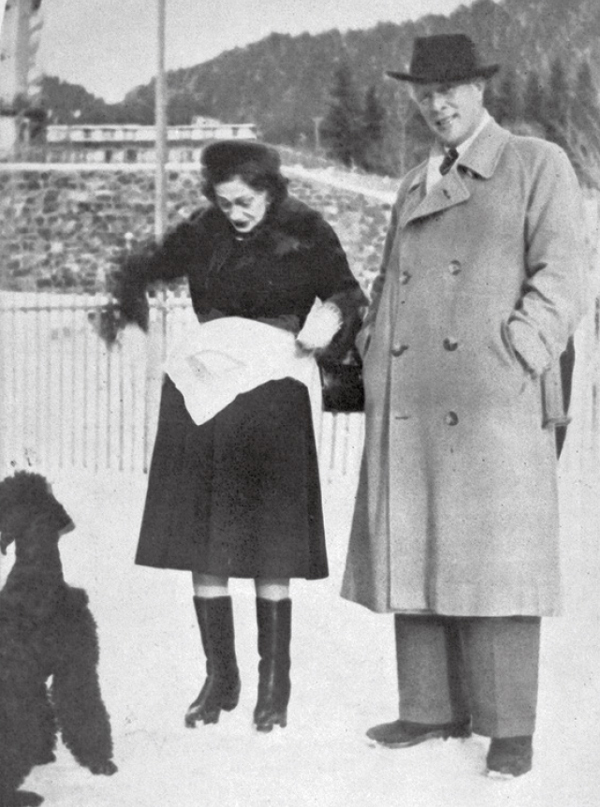

Coco and Spatz in 1951 at Villars-sur-Ollon, Canton of Vaud, Switzerland

A friend warned Coco of the danger of having a relationship with a German, but Coco said of Spatz, “He isn’t a German. His mother is English!” She and Spatz spoke English to each other. Coco later said they both loathed the war for disrupting their lives. Spatz had lived in Paris as a diplomat at the German embassy since 1928 and enjoyed dining in the best restaurants and yachting with his rich friends. During the war he and Coco didn’t go out in public but had dinner parties at the homes of an inner circle that included others who had remained in Paris, among them Picasso, Cocteau, Colette, and Misia. Misia disapproved of Coco socializing with a German. She hated the occupation and the anti-Jewish laws. At one gathering, Misia dared to confront an important German official.

In 1941 Jews in occupied France were forbidden to engage in business and professional activities. The Wertheimers, who managed Coco’s perfume and cosmetics business, were Jewish and had fled France in 1940. They made their way to New York City and continued producing Chanel No 5 in a factory in New Jersey. The Wertheimers sent a trusted American friend back to Paris to pick up the formula for the perfume from the company’s office and to Grasse to buy the necessary ingredients and smuggle the materials into the United States.

Coco felt she now had the opportunity to seize full control of the company. Like many French citizens, she resented Jewish refugees living in France during the 1930s. When Léon Blum, who was a Jew, had become premier in 1936, his accession to power had triggered a hate campaign against Jews, even though he and his ancestors were French born.

Before the Wertheimers left France, they had asked their non-Jewish business associate Félix Amiot, an industrialist, to front for them as the new co-owner. Nazi storm troopers brought Amiot in for questioning and accused him of serving as a cover for the Wertheimers. Coco followed up with a letter to the administrator who decided what would happen to businesses left by anyone who had fled France. She insisted that her perfume business was “still the property of Jews” and had been “legally ‘abandoned’ by the owners. I have,” she wrote, “an indisputable right of priority.” However, the Wertheimers had transferred ownership to Amiot before leaving the country, and the arrangement was judged “legal and correct.” So their partnership with Coco remained the same.

Sometimes Coco went to her villa on the Riviera. The architect who had designed La Pausa was a member of the local French Resistance group. Once, he asked her to intervene on behalf of a friend who had been arrested by the Gestapo, the German secret police, and she agreed. Unbeknownst to Coco, the cellars of her villa were used to hide a transmitter and to provide a way station for Jews escaping from France to the Italian border. Today, we still don’t know if she was a Nazi sympathizer or not. But what we do know is that what concerned her most was keeping and building her fortune after a childhood of poverty.

In the summer of 1943, Coco dreamed up a scheme to bring about peace talks. She spoke to Spatz’s colleague Captain Theodor Momm and proposed that she act as a messenger to her old friend Winston Churchill, who was now the British prime minister. Captain Momm later testified that at first he hesitated but then decided to report her idea to the chief of Nazi intelligence in Berlin. Some of the senior commanders secretly wanted to negotiate with the Allies to end the war. Momm arranged for Coco to travel to Madrid, Spain, and meet with the British ambassador and Churchill. News had spread that Churchill would stop in Madrid on his way back from a conference in Tehran, Iran, with U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt and Soviet premier Joseph Stalin.

Coco’s mission was code-named Operation Modellhut (Model Hat). She arrived in Madrid in December and checked into the Ritz hotel. At the British embassy, she learned that Churchill was ill. Word came that he had caught a “bad cold” after the conference in Tehran. But really he had pneumonia. From Tehran he had flown in secret to General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s headquarters in Tunisia. Exhausted and in pain, Churchill suffered a heart attack and stayed in Tunisia to recover. Did he seriously consider meeting Coco? All we know is that the British ambassador in Madrid told her that Churchill could see no one because of his grave illness. So Coco’s plan failed, and she returned home.

At last, on August 25, 1944, French and American troops liberated Paris. Coco had just turned sixty-one. In the streets people laughed and sang “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem. But those who had collaborated with the Germans were punished. Thousands were imprisoned. Malcolm Muggeridge, a British intelligence officer stationed in Paris, said, “Everyone was informing on everyone else.” Women who had been the girlfriends of Germans had their heads shaved and were paraded through the streets past jeering mobs. Coco, of course, had been romantically involved with a German too.

Muggeridge marveled at her shrewd move to escape punishment. She put up a sign in the window of her boutique announcing that her perfume was free for American GIs. They immediately lined up for bottles of Chanel No 5 “and would have been outraged if the French police had touched a hair on her head.” Booton Herndon, an interpreter in the Army Corps of Engineers, wrote, “There had been a shortage of [perfume] during the Occupation, of course, like anything else, but now suddenly it appeared. At the time the magic words in perfume were Chanel No 5.” An American wartime nurse remembered that she couldn’t bring home “an awful lot” of souvenirs. But there was one thing she treasured: “Chanel, the perfume.”

Still, two men from the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur arrested Coco and took her in for questioning. Before Coco left with them, she told her maid whom to contact if she didn’t come back immediately. Coco was released three hours later, “after a telephone call from Churchill.” She received an urgent message from someone unknown saying, “Don’t lose a minute . . . get out of France.” Within hours she took off in a chauffeured limousine for the safety of Switzerland.