7

Japanese: Three Scripts are Better than One

In Japan, as elsewhere, the history of writing is marked by both invention and staunch conservatism. Yet the Japanese have managed a unique balance between the two, on the one hand creating for themselves not just one but two syllabaries, while on the other hand continuing throughout their literary history to favor the Chinese logograms with which they first learned to write. The resulting syncretism of three scripts used simultaneously qualifies as the most complex writing system in modern use.

According to Japanese tradition, Chinese characters came to Japan with the arrival of Wani, a Korean scholar, at the court of Emperor  jin. Wani brought with him the Analects of Confucius and became tutor to one of

jin. Wani brought with him the Analects of Confucius and became tutor to one of  jin’s sons. It is not clear how accurate the legend is, or when exactly

jin’s sons. It is not clear how accurate the legend is, or when exactly  jin reigned, but somewhere between the late third century and the early fifth century AD, the Chinese written language came to Japan.

jin reigned, but somewhere between the late third century and the early fifth century AD, the Chinese written language came to Japan.

The Japanese court’s first reaction to the new technology was not to adapt the system to Japanese, but rather to learn Chinese, just as the Koreans had before them and as the Akkadians had once learned Sumerian. Such foreign language study is in fact a common response to the introduction of writing – a response justified not only by the difficulty of adapting an existing writing system to a very different language, but also by the fact that one of the important uses of written language is not actually writing, but reading. There was as yet nothing to read in Japanese. The Chinese, by contrast, had been literate for well over a thousand years and had produced great works such as the Confucian classics and the translations of and commentaries on the Buddhist scriptures.

By the seventh century the Japanese had begun to write for themselves. At first the only way they could do so was to write in Chinese, using Chinese characters arranged in Chinese syntax – in other words, with the words arranged in the order found in Classical Chinese. In a Chinese sentence, the verb is placed between the subject and the object, as it is in English. In Japanese, however, the verb always comes at the end, after the subject and the object. In this respect and in many others, Japanese is very different from Chinese. In fact, despite numerous worthy efforts, Japanese has not convincingly been shown to be genetically related to any other language, though Korean is generally considered the best candidate. Unlike Chinese, Japanese is rife with inflections and follows each noun with a particle that indicates its function in the sentence. The Chinese writing system contains no equivalents for these morphemes, and so Chinese characters could not straightforwardly be adapted to Japanese. Despite the fact that few Japanese could speak Chinese, writing in Classical Chinese became the official, educated style of writing prose and remained so for centuries.

It soon became clear, however, that not everything that Japanese writers wanted to say could be written in Chinese. For one thing, how should they write their names? Names are more than their meanings: they are inextricably bound to their pronunciations, which in this case were in Japanese. The written form of a name therefore had to reflect its pronunciation. There was a precedent for a solution to this problem, in the way the Chinese wrote foreign names or the untranslatable Sanskrit terms of Buddhism. They used characters for their phono-logical value, divorced from their meaning. This rebus-style use of characters always remained marginal in Chinese, but it was to become widespread in Japan and lead eventually to the development of its two native syllabaries.

A second stumbling block was honorifics. Speakers of Japanese showed respect to people they considered their social superiors by using a special set of pronouns and inflectional suffixes when addressing them. These distinctions could not be written in Chinese, but they were important to the Japanese. To solve this problem, certain characters were given peculiarly Japanese interpretations as honorifics. A style of “modified Chinese” developed, with Japanese honorifics and a more Japanese word order. The Chinese verb placement was confusing to Japanese readers and writers, and in informal works such as diaries and personal letters they tended to slip into a more natural verb-final style. However, it was not until the time of the Kamakura shogunate (1192–1333), during the feudal period, that official documents were allowed to stray from correct, Classical Chinese and began to be written in modified Chinese.

Works written in Chinese could be read back either in Chinese or, with some mental gymnastics, in Japanese. The individual characters could be pronounced either in Chinese or as Japanese words of equivalent meaning. For example,  , “mountain,” which is sh

, “mountain,” which is sh n in modern Mandarin, could be pronounced in Japan either in Chinese or as the native Japanese word yama. A full sentence of characters, if read back in Japanese, had to be reorganized to get the correct word order, and the reader had to infer the appropriate Japanese inflections and particles. Because of this flexibility of reading, it can be difficult to determine precisely what language early Japanese documents were intended to be read in. The modified Chinese style, with its Japanese honorifics and un-Chinese word order, seems to have been intended to be read in Japanese, or perhaps a Japanese–Chinese hybrid. Poetry that rhymed was clearly meant to be Chinese, as Japanese poetry did not rhyme. Other documents could have been read either way. However, many words relating to philosophy, education, and high culture were borrowed into Japanese from Chinese, so there was only one way to say the word, no matter which language one was supposedly reading in.

n in modern Mandarin, could be pronounced in Japan either in Chinese or as the native Japanese word yama. A full sentence of characters, if read back in Japanese, had to be reorganized to get the correct word order, and the reader had to infer the appropriate Japanese inflections and particles. Because of this flexibility of reading, it can be difficult to determine precisely what language early Japanese documents were intended to be read in. The modified Chinese style, with its Japanese honorifics and un-Chinese word order, seems to have been intended to be read in Japanese, or perhaps a Japanese–Chinese hybrid. Poetry that rhymed was clearly meant to be Chinese, as Japanese poetry did not rhyme. Other documents could have been read either way. However, many words relating to philosophy, education, and high culture were borrowed into Japanese from Chinese, so there was only one way to say the word, no matter which language one was supposedly reading in.

By the ninth century it is clear that many Chinese texts were being read in Japanese, as priests studying Buddhist texts began to annotate the characters with dots to show which words received which particles, helping readers to construct Japanese sentences out of Chinese text. This was no doubt cumbersome, but easier to do with logographic characters than with a phonological script. Many Japanese learned to read Chinese texts without actually learning Chinese.

From these texts, words flooded into educated Japanese from Chinese in much the same way that Latin and Greek words entered English and many other European languages. Yet Chinese and Japanese are even more different from each other than English and Greek, and the newly borrowed words had to be altered to fit Japanese. Chinese morphemes were generally each a single syllable, but the Japanese language allowed only very simple syllables. So some Chinese syllables were simplified and others were spread out into two syllables. Chinese words were stripped of their distinctive tones, while the phonemes they contained were converted into the nearest Japanese equivalents. These AD aptations caused rampant homophony in Japanese. A particularly egregious case is ka, which is the Chinese-based (Sino-Japanese) pronunciation of 31 different characters on the modern list of 1,945 commonly used kanji, as Chinese characters are known in Japan. Modern Mandarin pronunciations of the same characters are (in p ny

ny n) xià, xiá, ji

n) xià, xiá, ji , jià, ji

, jià, ji , hu

, hu , huà, huá, gu

, huà, huá, gu , guò, gu

, guò, gu , hu

, hu , k

, k , k

, k , hé, g

, hé, g , and gè.

, and gè.

The borrowing of Chinese words occurred in three major waves. The first began with the introduction of Buddhism, traditionally dated to AD 552 and credited to a missionary from Korea. The Japanese pronunciation of the new religious vocabulary was probably adapted from that of southern Wu Chinese dialects of the time (see appendix, figure A.4). The second wave took place during the Nara period (ad 710–93), a time of stable imperial government built around Confucian ideals and state-sponsored Buddhism. Students were sent to China to study, and government officials were sent on diplomatic missions. They brought home many new words associated with Confucian philosophy, government affairs, and secular education. The Japanese pronunciation of this large set of Chinese loanwords was adapted from the standard dialect of the ruling dynasty of the time, the Tang.

The third and smallest wave of borrowings occurred in the fourteenth century with the arrival of a new sect of Buddhism, Zen. These words are mostly concerned with Zen, and their pronunciation in Japanese was probably AD apted from their fourteenth-century pronunciation in Hangzhou, in southern China.

The effect of these multiple borrowings at different times and from different kinds of Chinese was to permanently complicate written Japanese. When kanji are read in Japanese each character may have up to three Sino-Japanese pronunciations, known as on readings, as the morpheme may be part of loanwords from up to three phases of borrowing, taken from three different Chinese languages. Additionally there is the kun reading – the native Japanese pronunciation of a word of the same meaning. Luckily, the majority of kanji have only one Sino-Japanese on pronunciation. In China characters also have many different pronunciations, but the variation there is from one dialect to another – within a dialect, a character usually has a single pronunciation. In Japan, the particular pronunciation to be used depends on context.

Sino-Japanese words, including new compound words made in Japan out of Sino-Japanese parts (many of which have since been borrowed back into China), now comprise about half the words in Japanese. Most simple, commonly used words remain Japanese, however. Compared to native words, Sino-Japanese words are considered more formal, technical, and precise, just as words of Latin and Greek origin are in English. In English, a word like water is an everyday, native English word. When the concept of “water” is used to make up scientific compound words, however, we use the Greek hydro- (in words like hydrology and hydroponics), or Latin aqua- (in words like aquatic and aquarium). If we were writing English like Japanese, the free-standing word water as well as hydro- and aqua- would be all written with the same character. We would then know that a word of a single character was to be read back as a native word (water), while the ones in compound words of technical vocabulary would receive a foreign pronunciation (hydro- or aqua-) depending on the topic of the word and the morphemes it was compounded with (-ology versus -ium).

The Chinese language left a permanent mark on Japanese, not only in its writing system and its vocabulary, but also in its phonology. Chinese words were adapted to fit Japanese syllables, but they also exerted their own pressure on Japanese syllables, creating what are known as heavy syllables, which contain either a long vowel or a final consonant: CVV (also noted CV ) or CVC. The types of closed (CVC) syllables in Japanese are still extremely restricted, but it is due to Chinese influence that they exist at all.

) or CVC. The types of closed (CVC) syllables in Japanese are still extremely restricted, but it is due to Chinese influence that they exist at all.

Meanwhile, as the Japanese intellectual class blossomed during the Nara period, writing in Chinese or even modified Chinese was found to be inadequate for certain purposes, even if texts could be translated into Japanese on the fly by an adequately nimble reader. Writers could express most of their ideas in Chinese, especially as they owed so much of their intellectual culture to the Chinese, but what about their poetry? Poetry, like names, is deeply rooted in sound, not just meaning. The form of poetry is untranslatable between languages as different as Chinese and Japanese. To write Japanese poetry, therefore, required a way of writing Japanese. The initial solution to this problem was to expand the rebus technique used to write Japanese names: Chinese characters were used for their syllabic values, not their meanings. A syllabic system of writing known as man’y gana emerged in the eighth century, named after the Man’y

gana emerged in the eighth century, named after the Man’y sh

sh collection of poetry compiled around 759. Early written poetry, such as that found in the Man’y

collection of poetry compiled around 759. Early written poetry, such as that found in the Man’y sh

sh , used a combination of characters used for their kun (native Japanese) readings and a syllabic use of characters for their sounds alone, the man’y

, used a combination of characters used for their kun (native Japanese) readings and a syllabic use of characters for their sounds alone, the man’y gana syllabary. Texts in this logosyllabic style faithfully represented the Japanese language, including all its particles and inflections.

gana syllabary. Texts in this logosyllabic style faithfully represented the Japanese language, including all its particles and inflections.

The man’y gana syllabary was large and inefficient. The syllabic value of a character could be derived from either its on reading or its kun reading. A number of different characters could be used for the same syllabic sound. Twelve different characters could spell ka, for example. This is a lot, but fewer than it could have been, considering the 31 kanji with that pronunciation. In the Man’y

gana syllabary was large and inefficient. The syllabic value of a character could be derived from either its on reading or its kun reading. A number of different characters could be used for the same syllabic sound. Twelve different characters could spell ka, for example. This is a lot, but fewer than it could have been, considering the 31 kanji with that pronunciation. In the Man’y sh

sh , 480 characters were used for their syllabic on values, and a smaller number for their syllabic kun values, all for the roughly 90 different Japanese syllables of the time.

, 480 characters were used for their syllabic on values, and a smaller number for their syllabic kun values, all for the roughly 90 different Japanese syllables of the time.

The man’y gana of early Japanese poetry is remarkably like Akkadian cuneiform, despite the lack of any visual similarity or historical connection. Both used a bulky logosyllabary, with phonological values being supplied by two different, unrelated languages (Sumerian and Akkadian being as different as Chinese and Japanese). Like Akkadian cuneiform, the Japanese system was cumbersome but worked: Japanese had become a written language. Nevertheless, writing in Japanese did not enjoy high prestige. Man’y

gana of early Japanese poetry is remarkably like Akkadian cuneiform, despite the lack of any visual similarity or historical connection. Both used a bulky logosyllabary, with phonological values being supplied by two different, unrelated languages (Sumerian and Akkadian being as different as Chinese and Japanese). Like Akkadian cuneiform, the Japanese system was cumbersome but worked: Japanese had become a written language. Nevertheless, writing in Japanese did not enjoy high prestige. Man’y gana was reserved for poetry and proper names; other eighth-century texts were in either proper Chinese or modified Chinese. Within the restricted field of poetry, however, the Man’y

gana was reserved for poetry and proper names; other eighth-century texts were in either proper Chinese or modified Chinese. Within the restricted field of poetry, however, the Man’y sh

sh had a tremendous literary influence, and its style, containing virtually no Chinese loanwords, became the model for native-style poetry. In the aesthetic context of poetry, native vocabulary was valued, in sharp contrast with the importance of Chinese in formal documents. Where people’s hearts were involved, they wrote in Japanese.

had a tremendous literary influence, and its style, containing virtually no Chinese loanwords, became the model for native-style poetry. In the aesthetic context of poetry, native vocabulary was valued, in sharp contrast with the importance of Chinese in formal documents. Where people’s hearts were involved, they wrote in Japanese.

The need to record the Japanese language accurately also arose in the cases of imperial rescripts and Shinto prayers, which were written in a style known as senmy gaki (imperial rescripts are senmy

gaki (imperial rescripts are senmy in Japanese). The Shinto prayers were of native Japanese origin and were supposed to be repeated accurately, word for word. Similarly, the emperor’s words were taken down so as to be read back exactly, and of course the emperor spoke Japanese. In senmy

in Japanese). The Shinto prayers were of native Japanese origin and were supposed to be repeated accurately, word for word. Similarly, the emperor’s words were taken down so as to be read back exactly, and of course the emperor spoke Japanese. In senmy gaki, kanji were used with their kun readings, with the particles and inflection written in smaller man’y

gaki, kanji were used with their kun readings, with the particles and inflection written in smaller man’y gana characters. The result was the first truly Japanese prose.

gana characters. The result was the first truly Japanese prose.

The Nara period was succeeded by the Heian period, which lasted from 794 until 1192. During the first hundred years, Japanese literature languished, but the tools with which to create it were refined, and the two Japanese syllabaries still in modern use were born.

Japan’s first native syllabary, hiragana, developed out of a cursive version of man’y gana characters. (The shared element -gana of hiragana and man’y

gana characters. (The shared element -gana of hiragana and man’y gana is derived from kana and means “syllabary.” In the formation of certain compound words the k becomes a g – a “hard” [g] sound – while in others it remains k.) The cursive man’y

gana is derived from kana and means “syllabary.” In the formation of certain compound words the k becomes a g – a “hard” [g] sound – while in others it remains k.) The cursive man’y gana characters were reduced to simple, rounded shapes of only a few strokes apiece. The result was hiragana, “smooth kana.” Even an inexperienced eye can pick out the hiragana in a page of modern Japanese, as the signs are noticeably more curved – and usually simpler – than the accompanying kanji. The word kanji, for example, is written (in kanji)

gana characters were reduced to simple, rounded shapes of only a few strokes apiece. The result was hiragana, “smooth kana.” Even an inexperienced eye can pick out the hiragana in a page of modern Japanese, as the signs are noticeably more curved – and usually simpler – than the accompanying kanji. The word kanji, for example, is written (in kanji)  , while kana (in hiragana) is the much simpler

, while kana (in hiragana) is the much simpler  . The circular element at the bottom of the na sign would never occur in (noncursive) kanji, where only slight curves are permitted.

. The circular element at the bottom of the na sign would never occur in (noncursive) kanji, where only slight curves are permitted.

According to tradition, hiragana was invented by the sainted K b

b Daishi, founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Probably the tradition is not entirely accurate, as hiragana seems not to have fully taken shape within K

Daishi, founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Probably the tradition is not entirely accurate, as hiragana seems not to have fully taken shape within K b

b Daishi’s lifetime, from 774 to 835. Little documentation of the development of hiragana remains, but it seems to have been an evolutionary process rather than the invention of an individual or of a moment. Different ways of simplifying man’y

Daishi’s lifetime, from 774 to 835. Little documentation of the development of hiragana remains, but it seems to have been an evolutionary process rather than the invention of an individual or of a moment. Different ways of simplifying man’y gana characters were tried, and at first some of the man’y

gana characters were tried, and at first some of the man’y gana syllabary’s redundancy was inherited, with more than one sign for the same syllable. Eventually, a lean syllabary of 50 signs was achieved.

gana syllabary’s redundancy was inherited, with more than one sign for the same syllable. Eventually, a lean syllabary of 50 signs was achieved.

At nearly the same time, another form of kana was being created out of man’y gana characters. Buddhist monks and their students, poring over Chinese texts, would annotate the texts, showing the pronunciation of unfamiliar kanji, or recording the particles and inflections needed to turn the sentences into Japanese. The spaces between characters were not large, however, and students were often under time pressure as they took notes during lectures. In response to these pressures, they began writing only part of the man’y

gana characters. Buddhist monks and their students, poring over Chinese texts, would annotate the texts, showing the pronunciation of unfamiliar kanji, or recording the particles and inflections needed to turn the sentences into Japanese. The spaces between characters were not large, however, and students were often under time pressure as they took notes during lectures. In response to these pressures, they began writing only part of the man’y gana characters as a kind of abbreviation, giving birth to “partial kana” writing, or katakana. Abbreviated writing had been practiced before, both in Japan and in China, but the usefulness of this new kana, not just as shorthand but as a way of writing Japanese rather than Chinese, could not be overlooked. Like hiragana, katakana took a while to become standardized, with rival forms – varying in which part of the character got simplified, or which character got simplified – existing for some time.

gana characters as a kind of abbreviation, giving birth to “partial kana” writing, or katakana. Abbreviated writing had been practiced before, both in Japan and in China, but the usefulness of this new kana, not just as shorthand but as a way of writing Japanese rather than Chinese, could not be overlooked. Like hiragana, katakana took a while to become standardized, with rival forms – varying in which part of the character got simplified, or which character got simplified – existing for some time.

Because katakana was abbreviated from standard (noncursive) characters, it retains the angular shape of noncursive kanji, but is much simplified.  is “hiragana” in hiragana, while the same word appears more angular in katakana as

is “hiragana” in hiragana, while the same word appears more angular in katakana as  . In some cases the hiragana and katakana signs were based on the same man’y

. In some cases the hiragana and katakana signs were based on the same man’y gana character. Sometimes this is obvious: hiragana

gana character. Sometimes this is obvious: hiragana  and katakana

and katakana  (both ka) are derived from the

(both ka) are derived from the  character, meaning “to add,” which was also pronounced ka in its on reading and was used as one of the many man’y

character, meaning “to add,” which was also pronounced ka in its on reading and was used as one of the many man’y gana characters for that syllable. At other times the derivation from the same character is not obvious: hiragana

gana characters for that syllable. At other times the derivation from the same character is not obvious: hiragana  and katakana

and katakana  (me) are both derived from

(me) are both derived from  , pronounced me in its kun reading, meaning “female.” In other cases, due to the redundancies available in the man’y

, pronounced me in its kun reading, meaning “female.” In other cases, due to the redundancies available in the man’y gana syllabary, equivalent characters in hiragana and katakana were taken from different characters: hiragana

gana syllabary, equivalent characters in hiragana and katakana were taken from different characters: hiragana  ha (also used for the particle wa) is from

ha (also used for the particle wa) is from  ha, meaning “wave,” while the corresponding katakana sign,

ha, meaning “wave,” while the corresponding katakana sign,  , is taken from

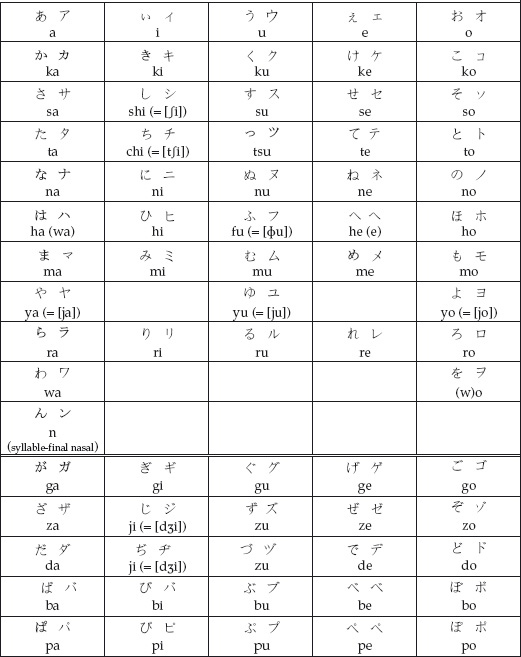

, is taken from  , meaning “eight” and pronounced hachi. Figure 7.1 shows the hiragana and katakana syllabaries.

, meaning “eight” and pronounced hachi. Figure 7.1 shows the hiragana and katakana syllabaries.

Unlike Akkadian or Mycenaean Greek, Japanese is well suited to be written with a syllabary. At the time the kana were being developed, Japanese consisted of only light syllables: CV (or just V). In their stabilized and standardized forms, hiragana and katakana each comprised 50 signs. Of these, 45 are still used. A forty-sixth has since been added, and new uses of some signs have been developed, to account for changes in the Japanese language since the ninth century. Due to the influence of Chinese, modern Japanese syllables may contain a long vowel or could be closed in one of two ways. First, a syllable may be closed by a nasal sound. If the nasal is followed by a consonant, it will be pronounced in the same part of the mouth as that following consonant, as in familiar Japanese words like tempura (itself a loanword from Portuguese) and Honda. If the nasal is not followed by a consonant it is pronounced as a rather indeterminate nasal sound far back in the mouth. The other way of closing a syllable in Japanese is by doubling the consonant that begins the next syllable. In a word like Hokkaido, for example, the first k closes the first syllable. The mouth remains closed, prolonging the k, until it is time to pronounce the vowel of the second syllable.

The forty-sixth sign – hiragana  and katakana

and katakana  – represents the adopted syllable-final nasal. A small version of the tsu syllable is used for the other kind of closed syllable:

– represents the adopted syllable-final nasal. A small version of the tsu syllable is used for the other kind of closed syllable:  in hiragana, or

in hiragana, or  in katakana, indicates that the upcoming consonant is doubled. Another special application of kana symbols occurs for what the Japanese call “twisted” sounds and linguists call palatalized. Palatalized consonants sound almost as if they are followed by a y ([j] in the International Phonetic Alphabet), and so are transliterated kya, kyu, kyo, etc. In kana they are written with two symbols, the second one written smaller to emphasize that there is actually only one syllable. So the syllable kya is written as though it were ki-ya:

in katakana, indicates that the upcoming consonant is doubled. Another special application of kana symbols occurs for what the Japanese call “twisted” sounds and linguists call palatalized. Palatalized consonants sound almost as if they are followed by a y ([j] in the International Phonetic Alphabet), and so are transliterated kya, kyu, kyo, etc. In kana they are written with two symbols, the second one written smaller to emphasize that there is actually only one syllable. So the syllable kya is written as though it were ki-ya:  . The representation of palatalized sounds did not begin until the middle of the Heian period, but it is not clear whether these syllables developed under the influence of Chinese, or were native but left out of the original kana in the interests of achieving a smaller, more easily memorized set of signs.

. The representation of palatalized sounds did not begin until the middle of the Heian period, but it is not clear whether these syllables developed under the influence of Chinese, or were native but left out of the original kana in the interests of achieving a smaller, more easily memorized set of signs.

Figure 7.1 The Japanese syllabaries, with hiragana on the left and katakana on the right. The Romanization follows the Hepburn style, with IPA interpretation where needed. The basic syllabaries are above the double line, secondary symbols with diacritics below. A smaller version of the tsu character is used for the first part of a double consonant.

The 46 basic signs do not distinguish between syllables that begin with g versus k, s versus z, or t versus d. These pairs of sounds are distinguished by the phonological property of voicing: in [g] the vocal cords are vibrating, creating a person’s voice, while in [k] the vocal cords do not vibrate, and the sound is effectively whispered. So, for example, ka and ga were originally both  in hiragana. Evidence from man’y

in hiragana. Evidence from man’y gana shows that Japanese of the Heian period did distinguish between voiced and voiceless sounds, but it is not unusual for a syllabary to ignore this difference in return for a smaller syllabary. Linear B did the same, and even English fails to mark one voicing distinction, spelling as th both the voiced [

gana shows that Japanese of the Heian period did distinguish between voiced and voiceless sounds, but it is not unusual for a syllabary to ignore this difference in return for a smaller syllabary. Linear B did the same, and even English fails to mark one voicing distinction, spelling as th both the voiced [ ] of either, and the voiceless [θ] of ether.

] of either, and the voiceless [θ] of ether.

In order to distinguish syllables with the voiced sounds g, z, d, and b from their voiceless counterparts, diacritical marks were added during the feudal period. So  is ka in hiragana and

is ka in hiragana and  is ga. Also added was a diacritical mark to distinguish syllables beginning with p from those beginning with h. At some point in the history of Japanese, [p] came to be pronounced as [h] (except before [u], where it is pronounced [Φ], a sound similar to [f]). The result was that [b] came to be considered the voiced equivalent of [h]:

is ga. Also added was a diacritical mark to distinguish syllables beginning with p from those beginning with h. At some point in the history of Japanese, [p] came to be pronounced as [h] (except before [u], where it is pronounced [Φ], a sound similar to [f]). The result was that [b] came to be considered the voiced equivalent of [h]:  is hiragana ha, and

is hiragana ha, and  is ba. A special diacritic is nowadays used to make pa:

is ba. A special diacritic is nowadays used to make pa:  . The [p] sound is now limited to doubled consonants (it is the doubled version of h), consonants occurring after the nasal, onomatopoeic words, and foreign loanwords.

. The [p] sound is now limited to doubled consonants (it is the doubled version of h), consonants occurring after the nasal, onomatopoeic words, and foreign loanwords.

Hiragana and katakana both evolved in the ninth century from the same source, man’y gana. However, they were developed, and continued to be used, in different environments. Katakana arose in the austere, masculine environment of Buddhist scholarship; its use in the Heian period was restricted to men. By the end of the Heian period, katakana had replaced the small man’y

gana. However, they were developed, and continued to be used, in different environments. Katakana arose in the austere, masculine environment of Buddhist scholarship; its use in the Heian period was restricted to men. By the end of the Heian period, katakana had replaced the small man’y gana characters for Japanese particles and inflections in the senmy

gana characters for Japanese particles and inflections in the senmy gaki style of writing, yielding a form of written Japanese that mixed kanji and katakana.

gaki style of writing, yielding a form of written Japanese that mixed kanji and katakana.

Meanwhile, hiragana came to be used at court by aristocratic women and their correspondents. Although they had not created it, women of the nobility adopted hiragana as their own. Studying kanji was not considered proper for women, but hiragana – perhaps because of its home-grown, informal associations – was fair game. In their hands, hiragana matured in the high cultural and aesthetic environment of the tenth-century Heian court. Aristocratic women studied calligraphy, composed and memorized poems, and wrote diaries. Women used their diaries to write colorful narrative memoirs in hiragana, while men recorded in theirs the day’s events in a more formal modified Chinese style. Women’s diaries became an established literary genre, to the extent that one man, Ki no Tsurayuki, had to circulate his hiragana diary in 935 under a female pseudonym. Part of Sei Sh nagon’s Pillow Book of around 1001, one of the two most famous works of the period, is in diary style, though it also contains poems, opinion essays, and lists.

nagon’s Pillow Book of around 1001, one of the two most famous works of the period, is in diary style, though it also contains poems, opinion essays, and lists.

Noblewomen were highly protected creatures, hidden from view behind screens and curtains. From there they had the leisure to observe and reflect on the characters and behavior of the people around them, and to incorporate their insights into their writing, giving Japanese fiction a new level of depth and maturity. Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji, written in the first decade or two of the eleventh century, is considered by many to be the world’s first true novel, as contrasted with earlier epics and tales with more two-dimensional characters.

Genji is not only a remarkable literary accomplishment; it is also a valuable first-hand account of the role of writing among the Heian nobility. Women could not be looked upon, but they could be corresponded with; and their beauty of soul and character was supposedly expressed in their handwriting. Great importance was laid on the kind of paper used, the elegance of the (hiragana) handwriting, and the allusive and literary beauty of the poems that were exchanged between correspondents. Despite the protective measures surrounding women, romantic affairs were frequent (though probably, then as now, more frequent in fiction than in real life) and were relatively well tolerated, provided the woman was single and the man’s rank did not disgrace her. Writing was crucial to the romance: by custom the successful consummation of an affair required a “morning after” letter from the man.

The literary style of Genji and other works of the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, mostly by women, marked a high point in Japanese literature. The style was almost pure Japanese, with very few Chinese loanwords. The deliberate cultivation of a high aesthetic in court circles was expressed in literature by the development of an elegant, evocative native style. The fact that the vocabulary was native – in the mother tongue, rather than the stilted, intellectual borrowed Chinese vocabulary – meant that both the hiragana prose and poetry of the period had an emotional resonance that other styles did not.

Paradoxically, this success at writing the mother tongue spelled the end of writing in a spoken style. Written down – fossilized – the graceful eleventh-century style was imitated in the writing of pure Japanese for centuries thereafter, with the result that the written and spoken languages soon diverged.

Although Japanese writing had come of age, having attained its own formalized, classical style, it was still not considered fit for official purposes. Official documents were still written in Chinese, and many male poets composed poetry in Chinese. Unofficially, however, the two separate written traditions – native Japanese in kana and formal Chinese in kanji – gradually began to merge. The beginnings of the modern compromise began to be reached as, starting in the twelfth century, literary styles appeared that were in Japanese but made free use of Chinese loanwords and were written in a mixture of kanji and kana, most often katakana.

In the succeeding feudal period (1192 to 1602), the first inklings of compromise touched officialdom. The influence of the imperial court and the old aristocracy was greatly diminished, and real power was in the hand of the shogun and of feudal lords. They were served by the samurai, men of the warrior class, who became the new bureaucrats. Without the education of their predecessors at the imperial court, the samurai gave up on proper Chinese and used modified Chinese in official documents.

The shogunate of Tokugawa Ieyasu ushered in a period of peace and prosperity known as the Edo period (1603 to 1867). Literacy spread from the highest-placed samurai throughout the warrior class. Schools were also established for children of commoners, and literacy in kana, with some kanji, began to spread. Printing techniques improved, and the publishing business prospered.

During the Edo period Japan was closed to outside influence, with small and carefully monitored exceptions made for Chinese, Korean, and Dutch traders. With the dawn of the succeeding Meiji era (1868 to 1911), Japan took stock of its position as compared to the West and decided it was time to modernize. Education was reformed and made compulsory. Written language, it was decreed, should more closely resemble the spoken language. Official documents were now to be written in Japanese syntax, with katakana mixed in with the kanji to provide particles and inflections. After more than a millennium’s dominance, writing in Chinese or modified Chinese finally lost its special status. The syntax of written Japanese, however, was still heavily influenced by the Classical Japanese of the Heian period until the twentieth century.

Japanese written style was far from homogeneous, however. Words could be written in kanji, in hiragana, or in katakana, or in some mixture of the three, the proportions in the mixture being open to variation. A small minority of zealous reformers even advocated replacing both kanji and kana with the Roman alphabet.

The present orthographic conventions in Japan are based on policies implemented after World War II. Modern Japanese writing finds a place for kanji, hiragana, and katakana, with the result that Japanese texts are written in three different scripts. Most nouns, verbs, and adjectives, plus some adverbs, are written in kanji. There are 1,945 characters on the government’s list of “common kanji,” with 284 more to be used in personal names and place names. The most frequently used 2,000 kanji account for 99 percent of the kanji in most texts. However, since specialized fields have their own specialized vocabulary, a total of 4,000 or 5,000 kanji are in active use in Japan today.

The 1,945 common kanji have, between them, 4,087 readings, a little over two readings per character, on average. Most have at least one Sino-Japanese (on) reading and at least one native (kun) reading. There may be more than one on reading, and there may also be more than one kun reading, as synonyms or near synonyms in the native vocabulary may be written with the same kanji. A fair number have only on readings. A few kanji have been created in Japan and therefore lack on readings (though one of them has actually acquired a pseudo- on reading). A few also lack on readings in the officially recommended list of kanji, due to the government’s efforts to rein in the explosion of kanji readings, but they have had on readings in the past.

Given the multiplicity of readings, it can be difficult to know how to read kanji, especially where proper names are involved (the same can be said of English, actually, where a family named Cholmondeley may live at Greenwich, on the Thames). Words consisting of a single kanji are usually read in their kun readings. Compounds are usually, but not always, given on readings, and the particular on reading will depend on the meaning of the compound. Some compounds are to be read as kun, though, and a few are mixed between on and kun.

Native Japanese words that are not assigned to a kanji are normally written in hiragana. This includes auxiliary verbs, many adverbs, and any other words whose kanji have become obsolete. Hiragana is also used for the particles that follow nouns, and for inflectional suffixes of nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Questions as to which kun reading of a character is intended are often resolved by the inflectional material in hiragana that follows, which may repeat part of the word stem as a kind of phonetic complement. For example, if the kanji  , meaning “to catch, grasp,” is followed by hiragana

, meaning “to catch, grasp,” is followed by hiragana  , raeru, then it is read toraeru. If it is followed by

, raeru, then it is read toraeru. If it is followed by  , maeru, then it is read tsukamaeru, another kun reading with the same basic meaning. Hiragana is also used to spell out the kun readings of kanji when needed.

, maeru, then it is read tsukamaeru, another kun reading with the same basic meaning. Hiragana is also used to spell out the kun readings of kanji when needed.

Katakana, on the other hand, serves a function in modern written Japanese much like that of italics in English. Like italics, it conveys emphasis. It also expresses that a particular word is not an everyday word of Japanese. An increasing number of words from European languages, and especially English, are flooding into Japanese. These modern loanwords appear in texts in katakana, as do foreign words and names transliterated into Japanese. Certain specialized names of plants, animals, and chemicals are written in katakana, especially in scientific writing. Some female given names lack a kanji version and are written in katakana. Another class of words written in katakana includes onomatopoeia and similar, often reduplicated words with evocative sounds (analogous to words like “eensy-weensy” or “pitter-pat” in English). Katakana is also used for specialized children’s vocabulary, exclamations, colloquialisms, and slang. Telegrams are written and sent in katakana. On readings of kanji are transliterated into katakana to distinguish them from kun readings, transliterated into hiragana.

The Japanese mixture of three scripts is a complicated writing system that takes years to master and discourages many a foreigner from even attempting to learn the language. Japanese readers are nowadays also exposed to increasing amounts of Romanized text, especially in advertising, raising the number of scripts used in some contexts to four. Yet anything written in Japanese could theoretically be written in either of the two kana scripts: why not just keep hiragana, say, and dispense with the rest? Hiragana is easily learned, and the Japanese language, with its simple syllable structure, is well suited to a syllabary. As compared to an alphabet, a syllabary is easy to learn to read. The process of sounding out words actually produces words: the pronunciation of the sequence of signs is the pronunciation of the word itself. Compare  “hiragana,” which can be read off as hi-raga-na, with a very simple alphabetic word like English bet. The word bet is not pronounced as the sequence of its letters, bee-ee-tee (phonetically [bi

“hiragana,” which can be read off as hi-raga-na, with a very simple alphabetic word like English bet. The word bet is not pronounced as the sequence of its letters, bee-ee-tee (phonetically [bi i

i ti

ti ]), nor of the sounds we tell children they stand for: [b

]), nor of the sounds we tell children they stand for: [b ε t

ε t ]. The consonant sounds that b and t represent are not pronounceable except when combined with vowel sounds. Sounding out words, therefore, involves far more than just learning the alphabet. By contrast, in a syllabary consonants and vowels come in precombined pronounceable packages. There are more symbols to memorize, but once they are learned, reading is easy. Indeed, most Japanese children learn hiragana before starting formal schooling. The educational system assumes children entering the first grade know hiragana, and concentrates on teaching katakana (first three grades) and kanji (the object of at least nine years of study).

]. The consonant sounds that b and t represent are not pronounceable except when combined with vowel sounds. Sounding out words, therefore, involves far more than just learning the alphabet. By contrast, in a syllabary consonants and vowels come in precombined pronounceable packages. There are more symbols to memorize, but once they are learned, reading is easy. Indeed, most Japanese children learn hiragana before starting formal schooling. The educational system assumes children entering the first grade know hiragana, and concentrates on teaching katakana (first three grades) and kanji (the object of at least nine years of study).

Though kana is easy, kanji are objectively difficult to learn – the more so because the phonetic complements embedded in kanji characters, vague enough in Chinese, have no bearing at all on their Japanese kun readings. Kanji that are seldom used are easily forgotten (though, to be fair, so are spellings in English). Despite its complexities, the kanji–kana mixed writing system is retained. And it works. Japan manages an impressive literacy rate: virtually all students emerge from the nine years of compulsory education with at least functional literacy of a level that enables them to hold productive jobs in their modern industrial society. Most people do better: a well-educated reader knows about 3,000 kanji, 1,000 more than the official list. A large number of classroom hours are devoted to studying written Japanese, yet Japan also does well at educating its students in math and science.

An important reason for the retention of such a complex writing system is the fact that the needs of the user and the needs of the learner of a technology are often quite different. A hiragana-only writing system would be simple to learn, and it would do its job adequately (especially if word spacing were added), but kanji would be sorely missed by experienced readers, and not only for sentimental reasons.

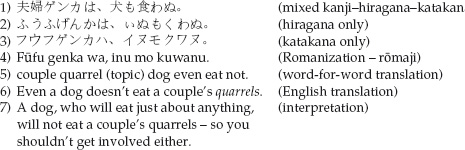

Figure 7.2 A Japanese proverb written in (1) a mixture of kanji, katakana, and hiragana, (2) hiragana only, (3) katakana only. Also given are the Romanization (known as r maji in Japanese), a word-for-word translation, English translation, and interpretation. To a Japanese reader, the kanji words for “couple,” “dog,” and “eat” stand out as content words. The use of katakana for the word for “quarrel” indicates emphasis; in kanji it would be

maji in Japanese), a word-for-word translation, English translation, and interpretation. To a Japanese reader, the kanji words for “couple,” “dog,” and “eat” stand out as content words. The use of katakana for the word for “quarrel” indicates emphasis; in kanji it would be  . The grammatical words and particles (topic marker, “even,” and negative particle) are in hiragana. Thus the first version provides more linguistic clues than the second or third (kana-only) versions.

. The grammatical words and particles (topic marker, “even,” and negative particle) are in hiragana. Thus the first version provides more linguistic clues than the second or third (kana-only) versions.

A text in mixed kanji–kana conveys a considerable amount of information that would be lost in a purely phonological script like hiragana. At a glance, the content words – which convey what the text is actually about – are distinguished from the grammatical words and suffixes, the former written in kanji and the latter in hiragana (see figure 7.2). The contrast between content words and grammatical words like the, in, at, with, and it is one that is nowhere marked in English orthography, but it is nevertheless a linguistically real distinction. By visually marking it, Japanese orthography gives clues to the syntactic function of its individual words. Skimming a text is made much easier, as the important words stand out from the grammatical window dressing.

Users of kanji also value the ability of the logograms to distinguish between homophones, of which Japanese has a large number, especially in its formal, Sino-Japanese vocabulary. If written in hiragana, the words  “four,”

“four,”  “city,”

“city,”  “paper,”

“paper,”  “arrow,” plus 43 other Sino-Japanese words would all be rendered simply as

“arrow,” plus 43 other Sino-Japanese words would all be rendered simply as  , shi. Understandably, writers resist such “simplification,” realizing that written language, divorced as it is from the interactive context of speech, must work harder to avoid ambiguity. In kanji, even if it isn’t obvious whether the on or kun reading is intended, the basic meaning will be clear. The Japanese writing system puts more emphasis on conveying the meaning of a word than on conveying its pronunciation.

, shi. Understandably, writers resist such “simplification,” realizing that written language, divorced as it is from the interactive context of speech, must work harder to avoid ambiguity. In kanji, even if it isn’t obvious whether the on or kun reading is intended, the basic meaning will be clear. The Japanese writing system puts more emphasis on conveying the meaning of a word than on conveying its pronunciation.

The use of katakana rather than hiragana also conveys useful linguistic information. In most uses, katakana signals that there is something unusual about the word recorded – it draws attention to it as a collection of sounds, outside the usual category of Japanese words. This is especially helpful in the case of loanwords. The restricted number of syllables in Japanese means that foreign words must be adjusted to fit a native shape. Because the writing is syllabic, this adjustment happens both in speech and in writing. The resulting words, if written in hiragana, would not signal their foreignness in the way that foreign words often do in alphabetic spellings. To take an example from English, Przewalski’s horses were clearly not named after an Englishman. English words do not contain prz-sequences, though the letters p, r, and z are all part of the writing system. In a syllabary, however, the syllabic adjustments to a foreign word make it look normal (although very strange to the foreigner: strawberry, for example, comes out sutoroberi). So it is the use of katakana that signals that the word is foreign.

The linguistic richness of the Japanese writing system exacted a price, however: Japan missed out on the typewriter age. The first successfully marketed American typewriter appeared in the 1870s. By contrast, the first Japanese kanji–kana typewriters came out only in 1915. These were monstrous things – expensive, slow, with huge trays full of symbols, and requiring specially trained operators. Few businesses could afford one; most subcontracted out their typing. The vast majority of office documents were handwritten.

The first katakana typewriter appeared in 1923, prior to the postwar script reforms that favored hiragana over katakana. It never became popular: by 1958 only about 10,000 katakana typewriters were in use in the entire country. They were fast, portable, and efficient, but people complained that they could not easily read the text. For one thing, the writing was horizontal, as compared to the traditional top-to-bottom orientation. For another, people found the spelling of homophones confusing, as also the inefficient, oddly spaced-out nature of the text, as it unrolled its message slowly, syllable by syllable. Typists had to remember to include spaces between words to avoid serious ambiguities (word spacing is not normally used in Japanese, as the switch from kanji to kana signals that one is reaching the end of a word). Nevertheless, some companies adopted katakana typewriters for their billing departments. In this restricted context they were adequate and efficient.

A hiragana typewriter was brought out in 1962, but it also failed to become popular. By this time, however, it was clear that Japan was falling behind the West in the area of office automation, in contrast with its impressive levels of industrial productivity. Fax machines and photocopiers were adopted enthusiastically, but could help only so much, as the originals of most office documents still had to be handwritten. Typing was reserved for a final, clean copy of documents when it was worth the expense. Proponents of Romanization and of kana-only writing had a strong argument: Japan should abandon kanji in order to keep its place as a modern, industrial nation. This would mean turning its back on its own history and entirely revamping its educational infrastructure, but wasn’t it worth it, for the sake of progress?

As it turned out, Japan’s history was saved by its technology. The prospects for kanji began to brighten in 1978, when Toshiba unveiled a word processor that could handle both kanji and kana. The user would type in kana and at the press of a button the word processor would convert appropriate stretches into kanji, giving the user choices in cases of homophones. (I have used the same basic system to type the Japanese in this chapter: I type on the Roman keyboard, which appears on screen in hiragana, which will convert to kanji if I press “enter.”)

The first word processor or waa puro as it became known in Japan (short for waado purosessaa), weighed 220 kilograms and cost 6.3 million yen (at the time, roughly $37,000 in American dollars). Not surprisingly, it was marketed to businesses and not to private individuals. Other companies soon brought out their own word processors, however, and prices began to drop in the 1980s. The year 1987 saw the application of artificial intelligence to Japanese word processing, greatly increasing the accuracy and efficiency of the kana-to-kanji conversion function.

Some of the most enthusiastic adopters of word processing were office workers who felt they had bad handwriting. Since the time of Genji at least, Japanese conventional wisdom has held that one’s handwriting is a window on one’s character. This belief led to a self-consciousness from which many a messy writer was pleased to escape. On the other hand, private individuals who enthusiastically embraced word processing were sometimes criticized for giving their personal correspondence an impersonal look, hiding their souls. Tradition has a valid point: handwritten material, its symbols shaped by the writer’s own body, carries along with its linguistic message a certain amount of personal information that is absent from a typed text, just as a spoken message in turn carries more information about the speaker (in its intonation, volume, and timbre of voice) than a written one does.

Not only has word processing allowed Japan to become competitive in the area of office automation, it has given Japan access to the Internet. Because of the late arrival of word-processing programs, Internet use was slow to catch on. But the nation has made up for lost time: Japanese is now the third most commonly used language on the Internet.

Besides the economic advantages of word processing, the technology has bolstered the private use of kanji. It is now easier for writers to use kanji that they may have partly forgotten (an effect similar to that of spell-checkers in English). Whereas a writer would once have resorted to hiragana in the face of a word whose kanji was forgotten or never mastered, with the waa puro a writer need only recognize characters, not create them perfectly from memory. The internal dictionary of the average word processor contains all 6,355 characters of Levels 1 and 2 of the Japan Industrial Standards, making available thousands more than the 1,945 of the government’s list of common kanji. A trend since the nineteenth century of using fewer and fewer kanji (and more kana) has been halted and may even be reversing. The chances of kana replacing kanji anytime in the near future are therefore slim and getting slimmer.

The Japanese word processor was created independently of Western models. The technology behind it spread to China, Taiwan, and South Korea, strengthening the hold of characters over each country in turn. The tradition of Chinese characters thus continues to bind the region together culturally. Where the characters are the same (and they are not always, as Japan and South Korea do not use the full range of characters, the People’s Republic of China has simplified some 2,000 of its characters, and Japan has independently simplified a few hundred), a reader of one of these languages can make some sense out of a text written in another, although certain meaning differences do exist between one country’s use of a character and another’s. Written phono-logically, however (either alphabetically or syllabically), a text in one language is entirely meaningless to speakers of the other languages.

Japan is not about to abandon kanji, the logograms its most revered author, Murasaki Shikibu, was not supposed to know – though she did. Yet the elegant hiragana syllabary in which Lady Murasaki wrote Genji is also alive and well, though relegated to a supporting role. The competing syllabary, katakana, has its place too. A complex but effective compromise has been reached in the Land of the Rising Sun.