11

King Sejong’s One-Man Renaissance

If Sequoyah had been born a royal prince of Korea, he might well have been like Sejong. Born in 1397, Sejong became the fourth king of Korea’s Chos n dynasty (1392–1910) in 1418 and ruled for 32 years. King Sejong’s accomplishments were many and diverse, but today, like Sequoyah, he is best remembered for the script he invented. These visionary men perceived that literacy was vital to the welfare of their peoples, both of which lived in the shadow of a more powerful nation (in Sejong’s case, China). With the added benefits of literacy, bilingualism, and a thorough education, Sejong was able to create the most efficient and logical writing system in the world. Those who trumpet the wonders of the Greek alphabet are misguided; it is the Korean alphabet which is the true paragon of scripts.

n dynasty (1392–1910) in 1418 and ruled for 32 years. King Sejong’s accomplishments were many and diverse, but today, like Sequoyah, he is best remembered for the script he invented. These visionary men perceived that literacy was vital to the welfare of their peoples, both of which lived in the shadow of a more powerful nation (in Sejong’s case, China). With the added benefits of literacy, bilingualism, and a thorough education, Sejong was able to create the most efficient and logical writing system in the world. Those who trumpet the wonders of the Greek alphabet are misguided; it is the Korean alphabet which is the true paragon of scripts.

Sejong was an extraordinary man: a brilliant scholar, an able ruler, and a generous humanitarian. The new Chos n (or Yi) dynasty had chosen Neo-Confucianism as its official philosophy, blaming state-sponsored Buddhism for the failings of their predecessors in the Kory

n (or Yi) dynasty had chosen Neo-Confucianism as its official philosophy, blaming state-sponsored Buddhism for the failings of their predecessors in the Kory dynasty (918–1392, the dynasty from which we get the name Korea). Sejong’s rare moral vision reflected the best of the Neo-Confucianism under which he had grown up.

dynasty (918–1392, the dynasty from which we get the name Korea). Sejong’s rare moral vision reflected the best of the Neo-Confucianism under which he had grown up.

The Confucianism Sejong upheld enjoined him to be a wise and benevolent ruler, to cultivate virtue, and to pursue learning as a means to achieve harmony with the cosmos. Few rulers have lived up to these ideals as well as Sejong. He ascended the throne at the age of 21 upon the abdication of his father, King T’aejong, and within two years had launched his very own Korean renaissance.

By 1420 Sejong had revitalized the royal academy (the Academy of Worthies), handpicking its roughly twenty members. With this elite group of men under his personal direction, Sejong presided over Korea’s golden age. He directed the scholars to pursue specific projects, but also instituted academic sabbaticals, giving them time off for personal study.

Not content merely to gather knowledge, Sejong turned immediately to its dissemination, and thus to printing. Korea had long ago learned the art of woodblock printing (xylography) from the Chinese and may have heard of Bi Sheng’s eleventh-century invention of ceramic movable type (typography). It is also possible that the Koreans had never heard of Bi Sheng, as the Chinese themselves had not taken his invention very seriously. It was Koreans, however, who in 1234 first used metal movable type (a bronze font of Chinese characters), over two centuries before Gutenberg invented his printing press. In 1392 the Publications Office was established, charged with the publishing of books and the casting of type. In practice, the office used only block printing until 1403, when King T’aejong ordered the casting of a new font, declaring the availability of reading material to be essential to good government. This lofty ideal was reportedly greeted with skepticism by some of his officials.

King Sejong, however, followed enthusiastically in his father’s footsteps. He ordered a new kind of type cast in 1420 which could be used more efficiently, increasing from about 20 to 100 the number of copies that could be printed from a single form in one day. He had another new font cast in 1434, again with advances in design. In 1436 he experimented with casting type from lead rather than bronze, and brought out a large-print type for the elderly.

Meanwhile, xylography flourished under Sejong as well. Block printing involved considerable expenditure of time and effort in the initial carving of blocks, but once carved a woodblock could last literally for centuries. Movable type was much faster to set up, but the type had to be painstakingly realigned after printing every page, and so printing was slow. Large print orders were therefore usually done with woodblocks, while movable type was used for smaller publications. Given Korea’s small population (and its truly tiny literate population), combined with Sejong’s concern with disseminating as many publications as possible, movable type was far more practical in Korea than it had ever been in China. In all, 114 works are known to have been printed with movable type and 194 printed with woodblocks during Sejong’s reign. By contrast, block printing of books was only just beginning in Europe during this period, and Gutenberg was still experimenting with typography in the late 1440s, thirty years into Sejong’s rule.

Like other educated men of his time, Sejong read and wrote in Classical Chinese, the Koreans having been the first people outside of China to adopt Chinese characters. At the latest, Chinese characters entered Korea with the establishment of the Han Prefectures, when China ruled northern Korea from 108 BC to AD 313. The Koreans themselves were using Chinese characters by 414, as evidenced by an inscribed stele erected in honor of King Kwangaet’o (ad 375–413). Chinese characters, however, are designed for the Chinese language, and Korean (aside from a large quantity of Chinese loanwords) is not at all like Chinese. (It is sometimes, though not conclusively, classified with the Altaic languages; it may also be distantly related to Japanese.) So literate Koreans wrote in Chinese. During their long acquaintance with Chinese characters, Koreans invented about 150 characters and added some specifically Korean meanings to Chinese characters. Chinese words entered the Korean language in droves.

Korea accepted China as its “elder brother,” with the Chinese emperor – theoretically at least – being the Korean king’s overlord. China was considered the source of all culture and learning. The Korean elite therefore thought it natural that becoming literate meant learning the Chinese language: everything worth reading was written in Chinese.

Some attempts were made to write Korean, however. At first, the native style of poetry was written in hyangchal, a system of using characters for their pronunciations that was similar to (and may have inspired) the Japanese man’y ;gana. Native Korean poetry declined during the Kory

;gana. Native Korean poetry declined during the Kory period, however, and with it hyangchal went out of use. Kugy

period, however, and with it hyangchal went out of use. Kugy l, analogous to early uses of katakana in Japan, was a system of simple and abbreviated characters that were inserted into Chinese texts to represent Korean grammatical elements and help Korean readers make sense of the Chinese grammar. Korean prose was written in idu (“clerk reading”), a system which used some characters for their meanings and others for their sounds. The oldest known idu text dates from 754; it remained the dominant method of writing Korean until 1894. Yet idu was looked down upon as vulgar by the literati. And indeed, it was a clumsy writing system that cried out to be superseded.

l, analogous to early uses of katakana in Japan, was a system of simple and abbreviated characters that were inserted into Chinese texts to represent Korean grammatical elements and help Korean readers make sense of the Chinese grammar. Korean prose was written in idu (“clerk reading”), a system which used some characters for their meanings and others for their sounds. The oldest known idu text dates from 754; it remained the dominant method of writing Korean until 1894. Yet idu was looked down upon as vulgar by the literati. And indeed, it was a clumsy writing system that cried out to be superseded.

Sejong, while never overtly questioning China’s suzerainty, had the audacity to realize that Korea was different from China. He came to the throne at a time when the Chos n dynasty was still fresh and hopeful, and the new state-sponsored Neo-Confuncianism was still being defined. Instead of slavishly copying China, Sejong looked for distinctively Korean ways to implement his ideas. Korea needed new rites and ceremonies, and appropriate music for them, so he ordered the compilation of manuals of ritual and protocol, and the composition and arranging of music, in first Chinese style and then native Korean. A unique style of Korean musical notation developed under his reign, the first East Asian system to fully represent rhythm.

n dynasty was still fresh and hopeful, and the new state-sponsored Neo-Confuncianism was still being defined. Instead of slavishly copying China, Sejong looked for distinctively Korean ways to implement his ideas. Korea needed new rites and ceremonies, and appropriate music for them, so he ordered the compilation of manuals of ritual and protocol, and the composition and arranging of music, in first Chinese style and then native Korean. A unique style of Korean musical notation developed under his reign, the first East Asian system to fully represent rhythm.

To teach Confucian morality, Sejong ordered the compilation of the Samgang haengsil (“Illustrated Guide to the Three Relationships”), a book of stories illustrating Confucian virtues. Unlike its earlier models, Sejong’s book contained examples drawn from Korean as well as Chinese sources. The king took care to have the book provided with large illustrations, aware that the vast majority of his subjects could not read. He issued statements encouraging the teaching of literacy to all classes of society, including (with a generosity unusual in his time) to women; but with a writing system as complex as idu and an educated class intent on keeping the privileges of literacy to themselves, nothing much happened.

Despite his scholarly bent, Sejong was no ivory-tower philosopher. His people needed more than morality and court ritual. Most importantly, the growing population needed food. Sejong set his academy to work on numerous scientific and technological projects directed toward increasing agricultural production. He commissioned a geographical survey of Korea; invented and distributed a rain gauge, instituting a nationwide meteorological network; and implemented irrigation systems. The optimal timing of sowing and harvest required an accurate calendar, he realized, not one calibrated to a Chinese latitude. He would have to derive a Korean calendar from scratch. In the course of his calendrical research Sejong invented (and/or had invented by his academy) an astrolabe, a water clock, and a sundial. His Publications Office printed seven books on agriculture and 32 calendars; it must have weighed on him that his farmers couldn’t read them.

King Sejong opened a medical school and even encouraged the education of female physicians so as to improve the health care available to women (who could not with propriety see a male doctor unless very seriously ill). He sponsored a compendious work of herbal medicine in 56 volumes, which again broke with Chinese tradition by emphasizing native Korean herbs, their uses, and where to find them.

For many years, beginning in 1422, Sejong worked on revising the Korean law code. Aware that bad law would make for bad precedents, he personally reviewed each article of the code with his legal scholars. Throughout his reign he showed a passion for justice, working to improve prison conditions, set fairer sentencing standards, implement proper procedures for autopsies, protect slaves from being lynched, punish corrupt officials, set up an appeals process for capital crimes, and limit torture. Nevertheless, one problem continued to vex the king: the litigation process was carried out in Chinese. Were the accused able to adequately defend themselves in a foreign language? Sejong doubted it.

Despite his achievements in agriculture, music, science, printing, and jurisprudence, Sejong was repeatedly stymied by the fact that his subjects couldn’t read. How could they learn about advances in technology if they couldn’t read? How could they benefit from moral philosophy if they couldn’t read? How could they defend themselves properly in a court of law if they couldn’t read?

Something must be done about it. Quietly, without telling his academy what he was about, Sejong set out to invent a script that matched the Korean language and could be easily learned by everyday people. The existing script he knew best was Chinese, but he knew that there were other ways to write. His government’s school for diplomats offered classes in Japanese, Jurchin, and Mongolian, besides spoken Chinese. Mongolian was taught in both the traditional vertical Mongol script and the newer ’Phags pa script. ’Phags pa was a squarish ak ara-based script modeled on Tibetan that had been developed at the command of Kublai Khan by the lama ’Phags pa Blo gros rgyal mtshan and completed in 1269. Kublai intended the script to be a universal writing system that could encode all the languages in his empire; in practice it was not used much. Nevertheless official edicts were often issued in ’Phags pa and it was useful for transcribing the correct pronunciation of Chinese characters. When the Mongol Yuan dynasty lost its hold on China in 1368 most people dropped ’Phags pa with relief.

ara-based script modeled on Tibetan that had been developed at the command of Kublai Khan by the lama ’Phags pa Blo gros rgyal mtshan and completed in 1269. Kublai intended the script to be a universal writing system that could encode all the languages in his empire; in practice it was not used much. Nevertheless official edicts were often issued in ’Phags pa and it was useful for transcribing the correct pronunciation of Chinese characters. When the Mongol Yuan dynasty lost its hold on China in 1368 most people dropped ’Phags pa with relief.

Sejong may well have studied ’Phags pa. He probably realized that some scripts directly represented their languages’ pronunciation rather than whole morphemes, thus using far fewer symbols than the logographic Chinese script. Sejong decided that he too would create a phonological script. He studied all the phonological science available at the time. He also learned spoken Chinese, becoming one of the few Koreans who could speak the Mandarin dialect of the time as well as read Classical Chinese.

Chinese phonologists had recognized that syllables contained two parts, an initial (or onset) and a final (or rhyme). Sejong, perhaps inspired by the representation of consonants in ’Phags pa, realized that a rhyme could have two parts (today known as the nucleus and the coda), and that the sounds that could end a syllable were the same sorts of sounds as those that could begin a syllable. In other words, the coda and the onset were both filled with consonants. Thus in a word like kuk, “country,” the [k] sound at the end and the [k] sound at the beginning were “the same thing” and could be represented with the same symbol. Sejong had discovered the phoneme. He went well beyond this discovery and established that phonemes fall into a number of different classes according to traits, or features, which they possess, such as whether they are vowels or consonants, where in the mouth they are pronounced, and whether they are aspirated. Although Sanskrit grammarians had organized the Indian alphabets according to these same sorts of classifications, Sejong took the unusual step of incorporating these phonological features into the design of the individual letters he created.

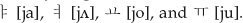

Known today as han’g l, the writing system Sejong invented was a wonder of simplicity and linguistic insight. To make it, he first systematically analyzed the phonology of his language – a job that, like the creation of a Korean calendar, he had to undertake from scratch, as no one had ever yet cared to subject vernacular Korean to linguistic study. First he divided consonants from vowels; that is, he divided the sounds that occur in the onset or coda of a syllable from those that constitute the nucleus of a syllable. Then he divided the consonants into five classes according to where in the mouth they are pronounced (the place of articulation, in modern terms), guided by the Chinese philosophical principle of analyzing almost everything into five classes to match the five elemental agents of Water, Wood, Fire, Metal, and Earth. The categories he arrived at were the labials (made with the lips, e.g. [m]), the linguals (what we now call alveolars, made with the tongue tip touching the alveolar ridge behind the top teeth, e.g. [n]), the dentals (made with the tongue tip touching or close behind the lower teeth, e.g. [s]; this class is today known as the sibilants), the molars (what we now call velars, made with the back of the tongue against the soft palate inside the back teeth, e.g. [k]), and the laryngeals (made in the throat, e.g. [h]; these are also known as glottals).

l, the writing system Sejong invented was a wonder of simplicity and linguistic insight. To make it, he first systematically analyzed the phonology of his language – a job that, like the creation of a Korean calendar, he had to undertake from scratch, as no one had ever yet cared to subject vernacular Korean to linguistic study. First he divided consonants from vowels; that is, he divided the sounds that occur in the onset or coda of a syllable from those that constitute the nucleus of a syllable. Then he divided the consonants into five classes according to where in the mouth they are pronounced (the place of articulation, in modern terms), guided by the Chinese philosophical principle of analyzing almost everything into five classes to match the five elemental agents of Water, Wood, Fire, Metal, and Earth. The categories he arrived at were the labials (made with the lips, e.g. [m]), the linguals (what we now call alveolars, made with the tongue tip touching the alveolar ridge behind the top teeth, e.g. [n]), the dentals (made with the tongue tip touching or close behind the lower teeth, e.g. [s]; this class is today known as the sibilants), the molars (what we now call velars, made with the back of the tongue against the soft palate inside the back teeth, e.g. [k]), and the laryngeals (made in the throat, e.g. [h]; these are also known as glottals).

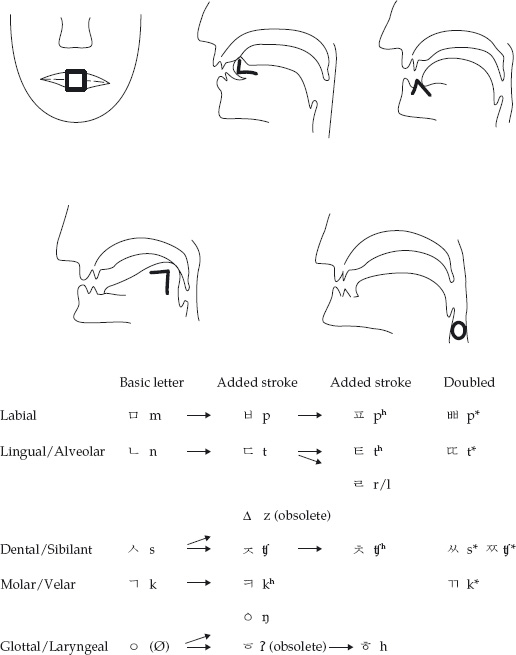

Having thus identified and classified the consonants of Korean, the next task was to assign them each a graphic shape. At this point Sejong had a stroke of absolute genius. He knew that the most basic Chinese characters had originally been pictograms and ideograms, though most characters of the developed script were compounds made up of a semantic radical and a pronunciation clue. The pictograms at the root of the Chinese script were pictures of things, as indeed were the pictograms at the root of cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and even the Semitic alphabet. Sejong, conscious that he was departing from Chinese practice in designing a script that recorded individual sounds rather than whole morphemes, created a wholly new form of pictogram. He drew pronunciations. Choosing one consonant in each of the five categories as basic (the one he considered least harshly articulated), he drew schematics of the formation of the consonant sounds in the mouth (see figure 11.1).

For the basic labial, [m], he drew a pictogram of a mouth,  , influenced by the Chinese character/pictogram for mouth,

, influenced by the Chinese character/pictogram for mouth,  . For the basic alveolar, [n], he drew the shape of the tongue as seen from the side, with its tip reaching up as it does when it touches the alveolar ridge:

. For the basic alveolar, [n], he drew the shape of the tongue as seen from the side, with its tip reaching up as it does when it touches the alveolar ridge:  . For the basic dental, [s], he drew a schematic of a tooth,

. For the basic dental, [s], he drew a schematic of a tooth,  , perhaps influenced by the Chinese character for tooth,

, perhaps influenced by the Chinese character for tooth,  , which depicts the incisors inside an open mouth. For the basic velar, [k], he again drew the shape of the tongue, this time with its back raised upward to touch the soft palate:

, which depicts the incisors inside an open mouth. For the basic velar, [k], he again drew the shape of the tongue, this time with its back raised upward to touch the soft palate:  . For the basic laryngeal he drew a circle depicting an open throat:

. For the basic laryngeal he drew a circle depicting an open throat:  . What precisely this letter stood for in Sejong’s time is unclear, as it now stands for the absence of a consonant in the onset of a syllable. What Sejong may have had in mind was the open throat preparatory to the voicing of the upcoming vowel, considering this to be a type of syllable onset in contrast to the closed throat of the glottal stop or the tensed throat that yields the breathy [h].

. What precisely this letter stood for in Sejong’s time is unclear, as it now stands for the absence of a consonant in the onset of a syllable. What Sejong may have had in mind was the open throat preparatory to the voicing of the upcoming vowel, considering this to be a type of syllable onset in contrast to the closed throat of the glottal stop or the tensed throat that yields the breathy [h].

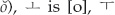

Armed with five basic shapes for the least harshly articulated consonant of each class, he proceeded to build the remaining consonants around these basic shapes. Plosive consonants were harsher than the nasals, while the affricate [t∫] was harsher than the fricative [s]. These harsher sounds were given an extra stroke:  was [p], derived from [m],

was [p], derived from [m],  (written so as to require one extra stroke);

(written so as to require one extra stroke);  was [t], derived from [n],

was [t], derived from [n],  was [t∫], derived from [s],

was [t∫], derived from [s],  . The glottal stop,

. The glottal stop,  , was similarly derived from the open-throat onset with a line on top of the

, was similarly derived from the open-throat onset with a line on top of the  , but the glottal stop and its symbol have since gone out of use in Korean.

, but the glottal stop and its symbol have since gone out of use in Korean.

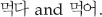

Figure 11.1 The derivation of the han’gãl letters from their pronunciations. Above, the positions of the lips, tongue, and throat that Sejong used to derive the basic shapes of the consonants. Below, the derivation of further consonants from the basic ones. Note that  and

and  are now a single letter.

are now a single letter.

Korean has a set of strongly aspirated stops and affricates, and to mark this set of yet harsher sounds the basic symbols were given a further modification, usually a further stroke:  was [ph],

was [ph],  was [th],

was [th],  was [t∫h],

was [t∫h],  was [kh], and

was [kh], and  was [h], the aspirated version of the open throat. Korean also has an unusual set of consonants that are held longer than regular consonants and are similar to doubled consonants in other languages except that they are pronounced with a tense vocal tract. These are sensibly written with double letters:

was [h], the aspirated version of the open throat. Korean also has an unusual set of consonants that are held longer than regular consonants and are similar to doubled consonants in other languages except that they are pronounced with a tense vocal tract. These are sensibly written with double letters:  and

and  . (Except for

. (Except for  , these tense phonemes seem not to have existed in Sejong’s time, and he used the doubling of a consonant letter to indicate the voiced consonants of Middle Chinese. The Modern Korean tense consonants have arisen since then out of earlier consonant clusters.)

, these tense phonemes seem not to have existed in Sejong’s time, and he used the doubling of a consonant letter to indicate the voiced consonants of Middle Chinese. The Modern Korean tense consonants have arisen since then out of earlier consonant clusters.)

A few consonant phonemes still needed symbols. One of them, pronounced either as [l] or [ ], depending on context – [l] when in the coda of a syllable or when doubled, and [

], depending on context – [l] when in the coda of a syllable or when doubled, and [ ] elsewhere – has an alveolar articulation, so Sejong gave it yet another variation on the basic

] elsewhere – has an alveolar articulation, so Sejong gave it yet another variation on the basic  shape:

shape:  . Another exception was the velar nasal, [

. Another exception was the velar nasal, [ ]. It is not entirely obvious why Sejong did not consider this the basic sound of the velar series, since the other nasals were considered basic in their classes, but perhaps it was because [

]. It is not entirely obvious why Sejong did not consider this the basic sound of the velar series, since the other nasals were considered basic in their classes, but perhaps it was because [ ] is unique in not being allowed to begin a Korean morpheme – making it a poor exemplar for the alphabetic principle. Instead he classified this sound with the laryngeals – a reasonable decision (though at odds with modern classification systems) given that in the pronunciation of [

] is unique in not being allowed to begin a Korean morpheme – making it a poor exemplar for the alphabetic principle. Instead he classified this sound with the laryngeals – a reasonable decision (though at odds with modern classification systems) given that in the pronunciation of [ ] the mouth is blocked off completely at the very back, leaving the sound to resonate only in the throat and nose. Sejong gave it a symbol based on the open-throat/absence of consonant:

] the mouth is blocked off completely at the very back, leaving the sound to resonate only in the throat and nose. Sejong gave it a symbol based on the open-throat/absence of consonant:  plus a short vertical line on top,

plus a short vertical line on top,  . Since Korean morphemes do not begin with [

. Since Korean morphemes do not begin with [ ] and the absence of consonant is not indicated at the ends of syllables, the two symbols have become conflated since Sejong’s time: at the beginning of a syllable

] and the absence of consonant is not indicated at the ends of syllables, the two symbols have become conflated since Sejong’s time: at the beginning of a syllable  stands for no consonant at all, while at the end it stands for [

stands for no consonant at all, while at the end it stands for [ ].

].

Having created symbols for consonants, Sejong turned to vowels. Again, he went about it philosophically and systematically. Of the vowels he chose three as basic: the one made with the lowest placement of the tongue [Å], the one made with the most forward placement of the tongue, [i], and one of the two made with the tongue drawn up and back, [ ] (the unrounded vowel transliterated as

] (the unrounded vowel transliterated as  ). He gave these three vowels symbols representing the mystical triad of heaven, earth, and humankind. The first he represented as a dot, ·, to represent the round heavens (this phoneme is no longer used in Korean). The second he made a vertical stroke, |, representing humankind, standing upright. The third became a horizontal line, the flat earth:

). He gave these three vowels symbols representing the mystical triad of heaven, earth, and humankind. The first he represented as a dot, ·, to represent the round heavens (this phoneme is no longer used in Korean). The second he made a vertical stroke, |, representing humankind, standing upright. The third became a horizontal line, the flat earth:  Other vowels were formed as combinations of these. The heavenly dot has evolved into a short line, easier to write with a brush. Thus

Other vowels were formed as combinations of these. The heavenly dot has evolved into a short line, easier to write with a brush. Thus  is [a],

is [a],  (transliterated

(transliterated  ),

),  is [u]. Diphthongs starting with a [j] onglide received a second dot (nowadays a line) to make

is [u]. Diphthongs starting with a [j] onglide received a second dot (nowadays a line) to make  . Other diphthongs were made by combining vowel symbols, though two of these are nowadays pronounced as single vowel phonemes, namely

. Other diphthongs were made by combining vowel symbols, though two of these are nowadays pronounced as single vowel phonemes, namely  (made from

(made from  and originally [aj] but now [ε]) and

and originally [aj] but now [ε]) and  (originally [Δj] but now [e]). Two other combined vowels,

(originally [Δj] but now [e]). Two other combined vowels,  , originally [oj] and [uj], are pronounced [we] and [wi] in some modern dialects but as single vowels [ø] and [y] in others.

, originally [oj] and [uj], are pronounced [we] and [wi] in some modern dialects but as single vowels [ø] and [y] in others.

It was time to put the consonants and vowels together. In Chinese each character is pronounced as a single syllable, and all are written the same size, regardless of complexity. Accordingly, Sejong grouped his newly created letters into syllabic blocks. The initial consonant went at the top left-hand side of the block. Next came the vowel, written to the right of the consonant if it contained a vertical stroke and otherwise below it. Thus  is the syllable ku, and

is the syllable ku, and  is ka, while a syllable without an initial consonant receives the null sign: ! is a. A final consonant is written at the bottom:

is ka, while a syllable without an initial consonant receives the null sign: ! is a. A final consonant is written at the bottom:  is kuk, “country,” and

is kuk, “country,” and  , mal, is “language.” Syllabic blocks together make up words:

, mal, is “language.” Syllabic blocks together make up words:  is han-kuk-mal, the Korean language.

is han-kuk-mal, the Korean language.

If a single consonant occurs between two vowels it is generally assigned to the onset of the second syllable, unless it is [ ]; thus the word ha’n

]; thus the word ha’n l, “sky,” is spelled

l, “sky,” is spelled  , but pang’ul, “bell,” is

, but pang’ul, “bell,” is  with [

with [ ] at the end of the first syllable block and the null consonant starting the second. Exceptions in modern orthography (following Sejong’s personal practice but revised from most other earlier spelling traditions) arise in order to keep constant the spelling of a morpheme. Thus the verb root

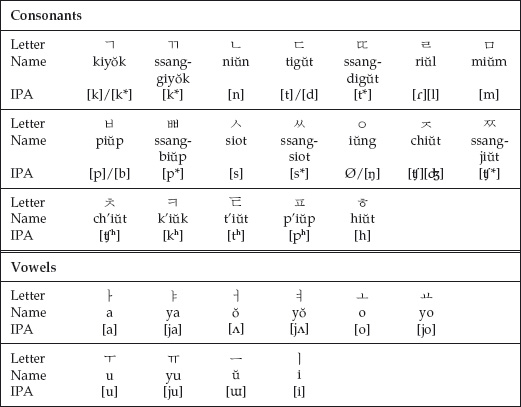

] at the end of the first syllable block and the null consonant starting the second. Exceptions in modern orthography (following Sejong’s personal practice but revised from most other earlier spelling traditions) arise in order to keep constant the spelling of a morpheme. Thus the verb root  (m

(m k, “to eat”) will be spelled the same, regardless of whether the suffix added to it starts with a vowel or a consonant; the root is clearly visible in both

k, “to eat”) will be spelled the same, regardless of whether the suffix added to it starts with a vowel or a consonant; the root is clearly visible in both  . The same morphemic convention allows consonant clusters to be spelled in syllable codas, even though they are not pronounced. The Korean word for “price” is

. The same morphemic convention allows consonant clusters to be spelled in syllable codas, even though they are not pronounced. The Korean word for “price” is  , pronounced [kap], with only a single final consonant. The extra

, pronounced [kap], with only a single final consonant. The extra  is there because if a vowel-initial suffix is added, there will be room to pronounce it:

is there because if a vowel-initial suffix is added, there will be room to pronounce it:  , with the -i suffix marking the word as the subject of the sentence, is pronounced [kap∫i] (s being pronounced [∫] before [i]). A similar principle drives the spelling in English of a word like iamb, with a silent unpronounceable letter that is heard only when a vowel-initial suffix is added, as in iambic.

, with the -i suffix marking the word as the subject of the sentence, is pronounced [kap∫i] (s being pronounced [∫] before [i]). A similar principle drives the spelling in English of a word like iamb, with a silent unpronounceable letter that is heard only when a vowel-initial suffix is added, as in iambic.

The constant-morpheme principle is also applied to the spelling of single final consonants. The number of consonants that can be pronounced in Korean syllable codas is quite restricted. The phonemes represented by  are all pronounced as

are all pronounced as  , [t], at the end of a syllable, but they will reappear with their distinctive pronunciations if a vowel-initial morpheme is added. Similarly the tense and aspirated plosives sound like their plain versions in codas but will be spelled according to how they sound when they are followed by a vowel and allowed to show their true colors.

, [t], at the end of a syllable, but they will reappear with their distinctive pronunciations if a vowel-initial morpheme is added. Similarly the tense and aspirated plosives sound like their plain versions in codas but will be spelled according to how they sound when they are followed by a vowel and allowed to show their true colors.

In addition to symbols for all the phonemes of Korean, Sejong  developed a way to record the pitch-accent of the Korean of his time, placing one dot, two dots, or no dots to the left of a syllable to indicate the pitch with which it was to be pronounced. (Pitch-accent is similar to tone except that only one syllable of a word receives a distinctive pitch and the pitch of other syllables is predictable from that one.) Standard modern Korean has lost its system of pitch-accent, and the side dots are no longer used.

developed a way to record the pitch-accent of the Korean of his time, placing one dot, two dots, or no dots to the left of a syllable to indicate the pitch with which it was to be pronounced. (Pitch-accent is similar to tone except that only one syllable of a word receives a distinctive pitch and the pitch of other syllables is predictable from that one.) Standard modern Korean has lost its system of pitch-accent, and the side dots are no longer used.

While he was about it, Sejong also incorporated extensions of the new script so as to be able to transcribe Chinese. With these modifications, han’g l

l  could be used to teach the proper pronunciation of Chinese.

could be used to teach the proper pronunciation of Chinese.

The system that Sejong ended up with is indeed the paragon of scripts (figure 11.2). It matches the phonology of the Korean language perfectly, and it is elegant and easy to learn. It encodes a large range of linguistic insights. In common with the Indian alphasyllabaries it recognizes the difference between vowels and consonants, a difference that is entirely ignored in linear, Greek-descended alphabets. It encodes individual phonemes, but also provides phonological information on a smaller scale than the phoneme, again in contrast with Western alphabets that recognize only phonemes. Similar phonemes are given predictably similar shapes; this property not only reflects the linguistic insight that phonemes are composed of smaller distinctive features, but is a crucial factor in making the han’g l alphabet so easy to learn. By contrast, the Roman alphabet abounds with pitfalls for the learner: the graphic similarity between the letters E and F corresponds to no phonological similarity at all, nor does the similarity between O and Q, while the similar phonemes written T and D look entirely dissimilar.

l alphabet so easy to learn. By contrast, the Roman alphabet abounds with pitfalls for the learner: the graphic similarity between the letters E and F corresponds to no phonological similarity at all, nor does the similarity between O and Q, while the similar phonemes written T and D look entirely dissimilar.

Figure 11.2 Han’g l, the Korean alphabet, listed in the South Korean order. The vowels are here presented separately, but in the alphabetization of actual words all vowel-initial words begin with the dummy consonant

l, the Korean alphabet, listed in the South Korean order. The vowels are here presented separately, but in the alphabetization of actual words all vowel-initial words begin with the dummy consonant  and will therefore appear after words beginning with

and will therefore appear after words beginning with  and before words beginning with

and before words beginning with  . The Korean names of the letters are given in Romanization. The name of each consonant contains that consonant twice – as the initial and final letter – which serves to indicate how the letter is pronounced when syllable-initial and when syllable-final. In the phonetic transcriptions given here, the tense consonants of Korean are transcribed with an asterisk. While common among linguists, this usage is not official IPA; these consonants do not yet have a standard IPA transcription.

. The Korean names of the letters are given in Romanization. The name of each consonant contains that consonant twice – as the initial and final letter – which serves to indicate how the letter is pronounced when syllable-initial and when syllable-final. In the phonetic transcriptions given here, the tense consonants of Korean are transcribed with an asterisk. While common among linguists, this usage is not official IPA; these consonants do not yet have a standard IPA transcription.

Han’g l also recognizes that phonemes are grouped together into syllables and morphemes. Speech as we hear it is naturally divided into syllables; it is also easy to realize that complex words are composed of meaningful parts (morphemes). But the meaningless and often unpronounceable phoneme is a concept that children learning linear alphabets must struggle with. By contrast, han’g

l also recognizes that phonemes are grouped together into syllables and morphemes. Speech as we hear it is naturally divided into syllables; it is also easy to realize that complex words are composed of meaningful parts (morphemes). But the meaningless and often unpronounceable phoneme is a concept that children learning linear alphabets must struggle with. By contrast, han’g l is generally taught to children as a pseudosyllabary, being presented first in simple syllables rather than as independent letters. As a result, Korean children can read before they begin their formal education.

l is generally taught to children as a pseudosyllabary, being presented first in simple syllables rather than as independent letters. As a result, Korean children can read before they begin their formal education.

The only serious drawback to han’g l has been its incompatibility with the typewriter. This Western innovation assumed a linear alphabet, and the non-linear alphabets of Korea and southern Asia – though no harder to read, write, or learn – have sometimes been considered inferior because they are so hard to type (a conclusion no doubt supported by a good measure of ethnocentrism). Fortunately, the word-processing programs of the digital age have largely done away with this objection. The user can type in the letters one after another, and the computer will arrange them into appropriate syllable blocks (similarly, the computer will correctly create Indic ak

l has been its incompatibility with the typewriter. This Western innovation assumed a linear alphabet, and the non-linear alphabets of Korea and southern Asia – though no harder to read, write, or learn – have sometimes been considered inferior because they are so hard to type (a conclusion no doubt supported by a good measure of ethnocentrism). Fortunately, the word-processing programs of the digital age have largely done away with this objection. The user can type in the letters one after another, and the computer will arrange them into appropriate syllable blocks (similarly, the computer will correctly create Indic ak aras, or choose the word-initial, -medial, or -final version of a letter in Arabic).

aras, or choose the word-initial, -medial, or -final version of a letter in Arabic).

Although later historians have tended to assume that Sejong could not have succeeded in designing such a marvelous script without the assistance of his academy, the records of the time are unequivocal in calling the Korean alphabet the king’s personal creation, in contrast with other inventions of the period, for which the credit is more evenly divided. He announced his creation in the last month of the lunar year 1443 – somewhere around January 1, 1444, in our solar calendar.

Fierce objections to Sejong’s work surfaced almost immediately, led by Ch’oe Mal-li, vice-director of Sejong’s own academy. Why was the king endangering good relations with China by so visibly deviating from Chinese practices? Why would the king of a self-respecting country want to imitate barbarians such as the Mongols, the Jurchin, and the Japanese? Only barbarians used scripts other than Chinese characters. Furthermore, by lowering standards of literacy, the new alphabet would lead to rampant cultural illiteracy as people would neglect the study of Classical Chinese and of high culture. Surely the king didn’t want that?! The king’s hope that a vernacular script would help prevent miscarriages of justice was misplaced, as witness China, where the language matched the writing system but injustice was not unknown. The king was behaving with great imprudence on a matter with potentially profound consequences without having consulted any of his ministers. Was the king further going to endanger his health and the welfare of the nation by continuing to work on his alphabet project on the upcoming retreat he was taking for his health, during which all inessential work was to be handed over to his ministers? And would he meanwhile waste the crown prince’s time on it too?

The king may indeed have wished to distance his country from China, and he must have realized that his plan to educate the masses was a threat to the social order treasured by Ch’oe Mal-li and his fellow literati; but he was wise enough not to say so. Instead he issued a sharp rejoinder presenting the new script as a boon to the Korean people – which he as king had every moral right to convey – and emphasizing its application for correcting and standardizing the pronunciation of Chinese characters – a scholarly project for which he was uniquely qualified. The crown prince, he added, would do very well to concern himself with a matter of such great national importance.

Having thus quashed the most vocal criticism, Sejong next put his new script through a rigorous trial run. He set the more alphabet-friendly scholars of his academy to compiling the Yongbi  ch’

ch’  n ka, or “Songs of Flying Dragons,” a work of history and poetry praising Sejong’s grandfather and founder of the Chos

n ka, or “Songs of Flying Dragons,” a work of history and poetry praising Sejong’s grandfather and founder of the Chos n dynasty, Yi S

n dynasty, Yi S nggye.

nggye.

Confident that his new script was working as intended, on October 9, 1446, Sejong finally made public his Hunmin ch ng’

ng’  m, “The Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People,” the name by which he titled both his script and the short promulgation document he wrote explaining it. In the Hunmin ch

m, “The Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People,” the name by which he titled both his script and the short promulgation document he wrote explaining it. In the Hunmin ch ng’

ng’  m, each symbol is presented with an example of a Chinese character containing that sound. In its short but moving preface Sejong explains his motivation for introducing a new writing system:

m, each symbol is presented with an example of a Chinese character containing that sound. In its short but moving preface Sejong explains his motivation for introducing a new writing system:

The speech sounds of our country’s language are different from those of the Middle Kingdom and are not communicable with the Chinese characters. Therefore, when my beloved simple people want to say something, many of them are unable to express their feelings. Feeling compassion for this I have newly designed twenty-eight letters, only wishing to have everyone easily learn and use them conveniently every day.

Appended to his brief document was the much longer Hunmin ch ng’

ng’ m haerye, “Explanatory Notes and Examples of Usage of the Hunmin ch

m haerye, “Explanatory Notes and Examples of Usage of the Hunmin ch ng’

ng’ m,” written by scholars of the academy, led by Ch

m,” written by scholars of the academy, led by Ch ng In-ji. The Hunmin ch

ng In-ji. The Hunmin ch ng’

ng’ m haerye explained the philosophical and linguistic principles underlying its design, including the rationale for the letter shapes. (This part of the document was unfortunately lost from about 1500 until 1940.) In a laudatory postface Ch

m haerye explained the philosophical and linguistic principles underlying its design, including the rationale for the letter shapes. (This part of the document was unfortunately lost from about 1500 until 1940.) In a laudatory postface Ch ng In-ji wrote “an intelligent man can acquaint himself with them [the letters] before the morning is over, and even the simple man can learn them in the space of ten days,” adding, with some justification, that “under our Monarch with his Heaven-endowed wisdom, the codes and measures that have been proclaimed and enacted exceed and excel those of a hundred kings.”

ng In-ji wrote “an intelligent man can acquaint himself with them [the letters] before the morning is over, and even the simple man can learn them in the space of ten days,” adding, with some justification, that “under our Monarch with his Heaven-endowed wisdom, the codes and measures that have been proclaimed and enacted exceed and excel those of a hundred kings.”

Sejong could have issued a proclamation enforcing the exclusive use of han’g l, but he did not do so. For someone who had just invented the most rational script in the world he showed prudent restraint in advancing its interests. He sponsored and printed works written in han’g

l, but he did not do so. For someone who had just invented the most rational script in the world he showed prudent restraint in advancing its interests. He sponsored and printed works written in han’g l, used it in official documents, and added knowledge of han’g

l, used it in official documents, and added knowledge of han’g l to the subjects tested in the civil service exam. But he stopped far short of imposing the new script on the likes of Ch’oe Mal-li, and the upper classes went right on writing in Chinese.

l to the subjects tested in the civil service exam. But he stopped far short of imposing the new script on the likes of Ch’oe Mal-li, and the upper classes went right on writing in Chinese.

Sejong died on April 18, 1450. Without him Korea’s golden age soon waned, and han’g l nearly died of neglect. His successor, Munjong, outlived him by only two years, and his grandson, Tanjong, was soon ousted by Munjong’s brother, Sejo. Sejo (1455–68) abolished the Academy of Worthies after usurping the throne, enraged at its members’ loyalty to Tanjong. He went on to publish Buddhist texts in han’g

l nearly died of neglect. His successor, Munjong, outlived him by only two years, and his grandson, Tanjong, was soon ousted by Munjong’s brother, Sejo. Sejo (1455–68) abolished the Academy of Worthies after usurping the throne, enraged at its members’ loyalty to Tanjong. He went on to publish Buddhist texts in han’g l for the benefit of the people, but han’g

l for the benefit of the people, but han’g l did not enjoy much further support. Among the educated it became known contemptuously as the “vernacular script,” “women’s script,” or even, with undisguised contempt, “morning script,” due to its reputation for being learnable in a morning. Anything that was that easy was clearly not worth wasting ink on.

l did not enjoy much further support. Among the educated it became known contemptuously as the “vernacular script,” “women’s script,” or even, with undisguised contempt, “morning script,” due to its reputation for being learnable in a morning. Anything that was that easy was clearly not worth wasting ink on.

Yet precisely because it was easy to learn, han’g l was able to survive this stepchild treatment. Finding refuge among Buddhists, women, and others excluded from power, it put down roots among the people, which enabled it, unlike Korea’s printing industry, to survive the sixteenth century. The Imjin War, as the Japanese invasions of 1592–8 were known, devastated the country, killing hundreds of thousands of people, laying waste the crop lands, and dealing the country a great cultural blow that stripped it of many of Sejong’s accomplishments. Its fine ceramics industry was destroyed, and the kilns and potters captured by the Japanese were used to jump-start the Japanese porcelain industry, earning the war the nickname of the “pottery war.” Korea’s type foundries and printing presses were also destroyed, and books, type, and printers were carried off to Japan. Metal type was not recast in Korea until 1668.

l was able to survive this stepchild treatment. Finding refuge among Buddhists, women, and others excluded from power, it put down roots among the people, which enabled it, unlike Korea’s printing industry, to survive the sixteenth century. The Imjin War, as the Japanese invasions of 1592–8 were known, devastated the country, killing hundreds of thousands of people, laying waste the crop lands, and dealing the country a great cultural blow that stripped it of many of Sejong’s accomplishments. Its fine ceramics industry was destroyed, and the kilns and potters captured by the Japanese were used to jump-start the Japanese porcelain industry, earning the war the nickname of the “pottery war.” Korea’s type foundries and printing presses were also destroyed, and books, type, and printers were carried off to Japan. Metal type was not recast in Korea until 1668.

Independent of the nation’s ruined infrastructure, han’g l survived. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw the birth of popular literature written in the vernacular script. It was only in 1894, however, that han’g

l survived. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw the birth of popular literature written in the vernacular script. It was only in 1894, however, that han’g l came into its own as the nationally sanctioned writing system. That year, as part of a series of reforms aimed at modernizing Korea and distancing it from China, King Kojong gave han’g

l came into its own as the nationally sanctioned writing system. That year, as part of a series of reforms aimed at modernizing Korea and distancing it from China, King Kojong gave han’g l official status. Government edicts were to be written in han’g

l official status. Government edicts were to be written in han’g l (with Chinese translation attached if desired) or in a system that mixed Chinese characters and han’g

l (with Chinese translation attached if desired) or in a system that mixed Chinese characters and han’g l (analogous to the Japanese mixture of kanji and kana). On April 7, 1896, the Independent newspaper took the revolutionary step of publishing only in han’g

l (analogous to the Japanese mixture of kanji and kana). On April 7, 1896, the Independent newspaper took the revolutionary step of publishing only in han’g l and introduced European-style word spacing.

l and introduced European-style word spacing.

Meanwhile, the first Protestant missionaries had arrived in Korea, armed with the New Testament in han’g l (translated with the help of Koreans living in Manchuria). The use of the people’s script in the Bible did much to make Christianity appealing to everyday Koreans, while the existence of the Bible, hymnals, and prayer books in turn promoted the use of han’g

l (translated with the help of Koreans living in Manchuria). The use of the people’s script in the Bible did much to make Christianity appealing to everyday Koreans, while the existence of the Bible, hymnals, and prayer books in turn promoted the use of han’g l.

l.

Resistance to change was strong, however. In 1895 Yu Kil-jun published “Things Seen and Heard While Traveling in the West” in han’g l, provoking sharp criticism. As a memoir, it was serious literature and should have used a more serious script.

l, provoking sharp criticism. As a memoir, it was serious literature and should have used a more serious script.

The Japanese occupation of 1910–45 was unkind to han’g l, but this probably sealed its fate as a source of patriotic pride to the Korean people. Han’g

l, but this probably sealed its fate as a source of patriotic pride to the Korean people. Han’g l received its modern name in 1913 from Chu Sigy

l received its modern name in 1913 from Chu Sigy ng, a Korean linguist, patriot, and editor at the Independent, the name being deliberately ambiguous between “Korean script” and “great script.” (In North Korea it is nowadays called Chos

ng, a Korean linguist, patriot, and editor at the Independent, the name being deliberately ambiguous between “Korean script” and “great script.” (In North Korea it is nowadays called Chos n’g

n’g l, “Korean script,” or simply uri k

l, “Korean script,” or simply uri k lcha, “our characters.”) In 1933 the Korean Language Society issued carefully thought-out orthographic principles, codifying the morphophonemic spelling system originally favored by Sejong.

lcha, “our characters.”) In 1933 the Korean Language Society issued carefully thought-out orthographic principles, codifying the morphophonemic spelling system originally favored by Sejong.

The Japanese government opposed the use of han’g l and attempted to officially suppress it in 1938. The Korean language was outlawed in schools; all education was in Japanese. By 1945, the illiteracy rate among Koreans was as high as 78 percent.

l and attempted to officially suppress it in 1938. The Korean language was outlawed in schools; all education was in Japanese. By 1945, the illiteracy rate among Koreans was as high as 78 percent.

The end of World War II brought the end of Japanese domination, and circumstances changed quickly for han’g l. North Korea inaugurated an aggressive literacy campaign which virtually eliminated illiteracy by 1949, though further work was needed to regain this level after the devastation of the Korean War. South Korea, while not as single-minded in its efforts, also made rapid progress. Today Korea as a whole boasts one of the world’s lowest illiteracy rates (proving, in North Korea, that a high literacy rate is no guarantee of economic success). North Korea abolished the use of Chinese characters in official texts in 1949, but up to 3,000 characters are still taught in secondary school and university for the sake of reading older texts. In South Korea, after much waffling, about 1,800 characters continue to be taught, and in a few contexts, such as space-conscious newspaper headlines, they are still used for words of Chinese origin.

l. North Korea inaugurated an aggressive literacy campaign which virtually eliminated illiteracy by 1949, though further work was needed to regain this level after the devastation of the Korean War. South Korea, while not as single-minded in its efforts, also made rapid progress. Today Korea as a whole boasts one of the world’s lowest illiteracy rates (proving, in North Korea, that a high literacy rate is no guarantee of economic success). North Korea abolished the use of Chinese characters in official texts in 1949, but up to 3,000 characters are still taught in secondary school and university for the sake of reading older texts. In South Korea, after much waffling, about 1,800 characters continue to be taught, and in a few contexts, such as space-conscious newspaper headlines, they are still used for words of Chinese origin.

Today Koreans are justly proud of King Sejong and their native script. South Korea observes October 9, the day Sejong promulgated his Hunmin ch ng’

ng’ m, as Han’g

m, as Han’g l Day. Korean linguists point out the inherent logic and systematicity of han’g

l Day. Korean linguists point out the inherent logic and systematicity of han’g l and champion its potential as an international phonetic alphabet. With modifications along the lines that Sejong pursued in transcribing Chinese, han’g

l and champion its potential as an international phonetic alphabet. With modifications along the lines that Sejong pursued in transcribing Chinese, han’g l could be adapted to other languages in the world and would do the job more systematically than the present International Phonetic Alphabet, based as it is on the arbitrary shapes of the Roman alphabet. While the chance of this happening may be small, linguists around the world nevertheless laud han’g

l could be adapted to other languages in the world and would do the job more systematically than the present International Phonetic Alphabet, based as it is on the arbitrary shapes of the Roman alphabet. While the chance of this happening may be small, linguists around the world nevertheless laud han’g l as the world’s easiest, most rational script. Sejong would be pleased.

l as the world’s easiest, most rational script. Sejong would be pleased.