Chapter 15

Making Cents of Money

In This Chapter

Understanding Chinese currencies

Understanding Chinese currencies

Knowing how (and where) to change money

Knowing how (and where) to change money

Cashing checks and charging to plastic

Cashing checks and charging to plastic

Exchanging money at banks and ATMs

Exchanging money at banks and ATMs

Leaving proper tips

Leaving proper tips

Qián 钱 (錢) (chyan) (money) makes the world go around. People make their money in all sorts of ways. Most ways are legitimate. (If you’ve attained yours through nefarious means, I’m not sure I want to know, so don’t tell me!) You may be one of those lucky people who win the lottery or receive a large inheritance you use to traipse to the other side of the world. Or perhaps you have a modest amount saved up from working hard and paying your bills on time, and you hope to make it go a long way. However you get your money, you find out how to change it (and then save it or spend it) with the help of this chapter.

Of course, family and friends are priceless, but you can’t very well support yourself or help those you love, much less donate to a charity of your choice, unless you have something to give. And that’s what life is really all about. (Unless, of course, your main goal in life is to buy a sports car, acquire rare works of art, and live in the south of France . . . in which case you need a lot of qián. All the more reason to read this chapter.)

In this chapter, I share with you important words and phrases for acquiring and spending money — things you can easily do nowadays all over the world. I give you some banking terms to help you deal with everything from live tellers to inanimate ATMs. I even give you tips on tipping.

Staying Current with Chinese Currency

Depending on where in Asia (or any place where Chinese is spoken) you live, work, or visit, you have to get used to dealing with different types of huòbì 货币 (貨幣) (hwaw-bee) (currency), each with its own duìhuànlǚ 兑换率 (兌換率) (dway-hwahn-lyew) (rate of exchange). See Table 15-1 for the Chinese versions of international currency and the following sections for the main forms of Chinese huòbì. I delve into currency exchange in the later section “Making and Exchanging Money.”

Table 15-1 International Currencies

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

Gǎngbì 港币 (港幣) |

gahng-bee |

Hong Kong dollar |

|

Měiyuán 美元 |

may-ywan |

U.S. dollar |

|

Ōu yuán 欧元 (歐元) |

oh ywan |

Euro |

|

Rénmínbì 人民币 (人民幣) |

run-meen-bee |

(mainland) Chinese dollar |

|

Rì yuán 日元 |

ir ywan |

Japanese dollar |

|

Xīn bì 新币 (新幣) |

shin bee |

Singapore dollar |

|

Xīn táibì 新台币 (新臺幣) |

shin tye-bee |

Taiwan dollar |

Rénmínbì (RMB) in the PRC

In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the equivalent of the U.S. dollar is the yuán 元 (ywan), also known as rénmínbì 人民币 (人民幣) (run-meen-bee) ([mainland] Chinese dollars [Literally: the people’s money]) or RMB. More than 1 billion people around the globe currently use this currency. As of July 2012, 1 U.S. dollar is equivalent to about 6.38 (mainland) Chinese dollars. Here’s how you say that in Chinese:

Yì měiyuán huàn liù diǎn sān bā yuán rénmínbì. 一美元换六点三八元人民币. (一美元換六點三八元人民幣.) (ee may-ywan hwahn lyo dyan sahn ba ywan run-meen-bee.) (One U.S. dollar is 6.38 (mainland) Chinese dollars.)

The Chinese yuán, which is a paper bill, comes in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 in rénmínbì. One yuán is the equivalent of 10 máo 毛 (maow), which may also be referred to as jiǎo 角 (jyaow) — the equivalent of 10 cents. Each máo is the equivalent of 100 fēn 分 (fun), which compare to American pennies. Paper bills, in addition to the yuán, also come in denominations of 2 and 5 jiǎo. Coins come in denominations of 1, 2, and 5 fēn; 1, 2, and 5 jiǎo; and 1, 2, and 5 yuán.

Want to know how much money I have right now in my pocket, Nosy? Why not just ask me?

Nǐ yǒu jǐ kuài qián? 你有几块钱? (你有幾塊錢?) (nee yo jee kwye chyan?) (How much money do you have?)

Nǐ yǒu jǐ kuài qián? 你有几块钱? (你有幾塊錢?) (nee yo jee kwye chyan?) (How much money do you have?)

Use this phrase if you assume the amount is less than $10.

Nǐ yǒu duōshǎo qián? 你有多少钱? (你有多少錢?) (nee yo dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much money do you have?)

Nǐ yǒu duōshǎo qián? 你有多少钱? (你有多少錢?) (nee yo dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much money do you have?)

Use this phrase if you assume the amount is greater than $10.

Xīn Táibì in the ROC

In Taiwan, also known as the Republic of China or ROC, 1 U.S. dollar equals about 30 xīn Táibì 新台币 (新臺幣) (shin tye-bee) (New Taiwan dollars). Here’s how you say that in Chinese:

Yì měiyuán huàn sānshí yuán xīn Táibì. 一美元 换三十元新台币. (一美元 換三十元新臺幣.) (ee may-ywan hwahn sahn-shir ywan shin tye-bee.) (One U.S. dollar is 30 New Taiwan dollars.)

You see bills in denominations of 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 and coins in denominations of 1, 5, 10, and 50 cents. Taiwanese coins are particularly beautiful — they have all sorts of flowers etched into them — so you may want to save a few to bring back to show friends (or just to have). Just make sure you keep enough língqián 零钱 (零錢) (leeng-chyan) (small change) on hand for all the great items you can buy cheaply at the wonderful night markets.

Hong Kong dollars

Hong Kong, the longtime financial dynamo of Asia, uses the Hong Kong dollar, or the Gǎngbì 港币 (港幣) (gahng-bee). Currently, 1 U.S. dollar is equivalent to 7.75 Hong Kong dollars. Here’s how you say that in Chinese:

Yì měiyuán huàn qī diǎn qī wǔ yuán Gǎngbì. 一美元换七点七五元港币. (一美元換七點七五元港幣.) (ee may-ywan hwahn chee dyan chee woo ywan gahng-bee.) (One U.S. dollar is 7.75 Hong Kong dollars.)

Singapore dollars

Singapore is a Mandarin-speaking country in Asia. Its dollars are called Xīn bì 新币 (新幣) (shin-bee) and come in denominations of 2, 5, 10, 50, and 100. You can find coins in denominations of 1 cent, 5 cents, 10 cents, 20 cents, 50 cents, and 1 dollar.

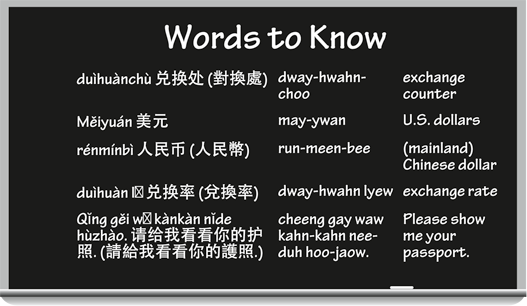

Exchanging Money

You can always huàn qián 换钱 (換錢) (hwahn chyan) (exchange money) the minute you arrive at the airport at the many duìhuànchù 兑换处 (兌換處) (dway-hwahn-choo) (exchange bureaus), or you can wait until you get to a major bank or check in at your hotel.

The following phrases come in handy when you’re ready to huàn qián:

Jīntiān de duìhuàn lǚ shì shénme? 今天的兑换率是什么? (今天的兌換率是甚麼?) (jin-tyan duh dway-hwahn lyew shir shummuh?) (What’s today’s exchange rate?)

Jīntiān de duìhuàn lǚ shì shénme? 今天的兑换率是什么? (今天的兌換率是甚麼?) (jin-tyan duh dway-hwahn lyew shir shummuh?) (What’s today’s exchange rate?)

Nǐmen shōu duōshǎo qián shǒuxùfèi? 你们收多少钱手续费? (你們收多少錢手續費?) (nee-men show dwaw-shaow chyan show-shyew-fay?) (How much commission do you charge?)

Nǐmen shōu duōshǎo qián shǒuxùfèi? 你们收多少钱手续费? (你們收多少錢手續費?) (nee-men show dwaw-shaow chyan show-shyew-fay?) (How much commission do you charge?)

Qǐng nǐ gěi wǒ sì zhāng wǔshí yuán de. 请你给我四张五十元的. (請妳給我四張五十元的.) (cheeng nee gay waw suh jahng woo-shir ywan duh.) (Please give me four 50-yuan bills.)

Qǐng nǐ gěi wǒ sì zhāng wǔshí yuán de. 请你给我四张五十元的. (請妳給我四張五十元的.) (cheeng nee gay waw suh jahng woo-shir ywan duh.) (Please give me four 50-yuan bills.)

Qǐngwèn, yínháng zài nǎr? 请问, 银行在哪儿? (請問, 銀行在哪兒?) (cheeng-one, eeng-hahng dzye nar?) (Excuse me, where is the bank?)

Qǐngwèn, yínháng zài nǎr? 请问, 银行在哪儿? (請問, 銀行在哪兒?) (cheeng-one, eeng-hahng dzye nar?) (Excuse me, where is the bank?)

Qǐngwèn, zài nǎr kěyǐ huàn qián? 请问, 在哪儿可以换钱? (請問在哪兒可以換錢?) (cheeng-one, dzye nar kuh-yee hwahn chyan?) (Excuse me, where can I change money?)

Qǐngwèn, zài nǎr kěyǐ huàn qián? 请问, 在哪儿可以换钱? (請問在哪兒可以換錢?) (cheeng-one, dzye nar kuh-yee hwahn chyan?) (Excuse me, where can I change money?)

Wǒ yào huàn yì bǎi měiyuán. 我要换一百美元. (我要換一百美元.) (waw yaow hwahn ee bye may-ywan.) (I’d like to change $100.)

Wǒ yào huàn yì bǎi měiyuán. 我要换一百美元. (我要換一百美元.) (waw yaow hwahn ee bye may-ywan.) (I’d like to change $100.)

Talkin’ the Talk

Jasmine:

Qǐngwèn, zài nǎr kěyǐ huàn qián?

cheeng-one, dzye nar kuh-yee hwahn chyan?

Excuse me, where can I change money?

Xíngliyuán:

Duìhuànchù jiù zài nàr.

dway-hwahn-choo jyoe dzye nar.

The exchange bureau is just over there.

Jasmine:

Xièxiè.

shyeh-shyeh.

Thank you.

Jasmine goes to the money exchange counter to change some U.S. dollars into Chinese yuán with the help of the chūnàyuán (choo-nah-ywan) (cashier).

Jasmine:

Nǐ hǎo. Wǒ yào huàn yì bǎi měiyuán de rénmínbì.

nee how. waw yaow hwahn ee bye may-ywan duh run-meen-bee.

Hello. I’d like to change USD $100 into (mainland) Chinese dollars.

Chūnàyuán:

Méiyǒu wèntí.

mayo one-tee.

No problem.

Jasmine:

Jīntiān de duìhuàn lǜ shì duōshǎo?

jin-tyan duh dway-hwahn lyew shir dwaw-shaow?

What’s today’s exchange rate?

Chūnàyuán:

Yì měiyuán huàn liù diǎn sān bā yuán rénmínbì.

ee may-ywan hwahn lyo dyan sahn ba ywan run-meen-bee.

One U.S. dollar is 6.38 (mainland) Chinese dollars.

Jasmine:

Hǎo. Qǐng gěi wǒ liǎng zhāng wǔshí yuán de.

how. cheeng gay waw lyahng jahng woo-shir ywan duh.

Great. Please give me two 50-yuán bills.

Chūnàyuán:

Méiyǒu wèntí. Qǐng gěi wǒ kànkàn nǐde hùzhào.

mayo one-tee. cheeng gay waw kahn-kahn nee-duh hoo-jaow.

No problem. Please show me your passport.

Spending Money

I don’t think I’ll have trouble selling you on (no pun intended) the thought of spending money. Whenever you see something you want, whether in a store, on the street, or at night market, you may as well give in to temptation and buy it, as long as you have enough qián. It’s as easy as that. Have money, will travel. Or, rather, have money, will spend.

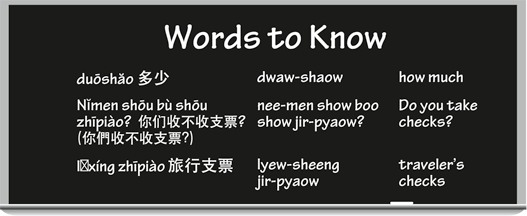

When you’re ready to buy something, you can do it with cash, check, or credit card. And when traveling overseas, you often use traveler’s checks.

You may overhear the following conversation in a store:

Zhèige hé nèige yígòng duōshǎo qián? 这个和那个一共多少钱? (這個和那個一共多少錢?) (jay-guh huh nay-guh ee-goong dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much are this and that altogether?)

Zhèige sān kuài liǎng máo wǔ, nèige yí kuài liǎng máo, suǒyǐ yígòng sì kuài sì máo wǔ. 这个三块两毛五, 那个一块两毛, 所以一共四块四毛五. (這個三塊兩毛五, 那個一塊兩毛, 所以一共四塊四毛五.) (jay-guh sahn kwye lyahng maow woo, nay-guh ee kwye lyahng maow, swaw-yee ee-goong suh kwye suh maow woo.) (This is $3.25, and that is $1.20, so altogether that will be $4.45.)

Before you decide to mǎi dōngxi 买东西 (買東西) (my doong-she) (buy things), be sure you have enough money yígòng to buy everything you want so you don’t feel disappointed after spending many hours in your favorite store.

Using cash

I don’t care what anybody tries to tell you, xiànjīn 现金 (現金) (shyan-jin) (cash) in local currency is always useful, no matter where you are and what time of day it is. Sometimes you can buy things and go places with xiànjīn that you can’t swing with a credit card. For example, if your kid hears the ice cream truck coming down the street, you can’t just whip out your xìnyòngkǎ to buy him an ice cream cone when the truck stops in front of your house. You can’t even try to convince the ice cream guy to take a zhīpiào 支票(紙票) (jir-pyaow) (check). For times like these, my friend, you need cold, hard xiànjīn. You can use it to buy everything from ice cream on the street to a movie ticket at the theater. Just make sure you put your money in a sturdy qiánbāo 钱包 (錢包) (chyan-baow) (wallet) and keep it in your front pocket so a thief can’t easily steal it.

Here’s how you speak of increasing amounts of money. You mention the larger units before the smaller units, just like in English:

sān kuài 三块 (三塊) (sahn kwye) ($3.00)

sān kuài yì máo 三块一毛 (三塊一毛) (sahn kwye ee maow) ($3.10)

sān kuài yì máo wǔ 三块一毛五 (三塊一毛五) (sahn kwye ee maow woo) ($3.15)

As useful and convenient as xiànjīn is, you really have to pay with zhīpiào for some things. Take your rent and electricity bills, for example. Can’t use cash for these expenses, that’s for sure. And when you travel overseas, everyone knows the safest way to carry money is in the form of lǚxíng zhīpiào 旅行支票 (lyew-sheeng jir-pyaow) (traveler’s checks) so you can replace them if they get lost or stolen.

Talkin’ the Talk

Heather goes shopping in Taipei and finds something she likes. She asks the clerk how much it is.

Heather:

Qǐngwèn, zhè jiàn yīfu duōshǎo qián?

cheeng-one, jay jyan ee-foo dwaw-shaow chyan?

Excuse me, how much is this piece of clothing?

Clerk:

Èrshíwǔ kuài.

are-shir-woo kwye.

It’s $25.

Heather:

Nǐmen shōu bù shōu zhīpiào?

nee-men show boo show jir-pyaow?

Do you take checks?

Clerk:

Lǚxíng zhīpiào kěyǐ. Xìnyòng kǎ yě kěyǐ.

lyew-sheeng jir-pyaow kuh-yee. sheen-yoong kah yeah kuh-yee.

Traveler’s checks are okay. Credit cards are also okay.

Paying with plastic

The xìnyòng kǎ 信用卡 (sheen-yoong kah) (credit card) may be the greatest invention of the 20th century — for credit card companies, that is. Everyone else is often stuck paying all kinds of potentially exorbitant lìlǚ 利率 (lee-lyew) (interest rates) if they’re not careful. Still, credit cards do make paying for things much more convenient, don’t you agree?

To find out whether a store accepts credit cards, all you have to say is

Nǐmen shōu bù shōu xìnyòng kǎ? 你们收不收信用卡? (你們收不收信用卡?) (nee-men show boo show sheen-yoong kah?) (Do you accept credit cards?)

Whether the jiàgé 价格 (價格) (jyah-guh) (price) of the items you want to buy is guì 贵 (貴) (gway) (expensive) or piányì 便宜 (pyan-yee) (cheap), the xìnyòng kǎ comes in handy.

Read on for a list of credit-card-related terms:

shēzhàng de zuì gāo é 赊帐的最高额 (賒帳的最高額) (shuh-jahng duh dzway gaow uh) (credit line)

shēzhàng de zuì gāo é 赊帐的最高额 (賒帳的最高額) (shuh-jahng duh dzway gaow uh) (credit line)

shōu 收 (show) (accept)

shōu 收 (show) (accept)

xìnyòng 信用 (sheen-yoong) (credit)

xìnyòng 信用 (sheen-yoong) (credit)

xìnyòng xiàn’é 信用限额 (信用限額) (sheen-yoong shyan-uh) (credit limit)

xìnyòng xiàn’é 信用限额 (信用限額) (sheen-yoong shyan-uh) (credit limit)

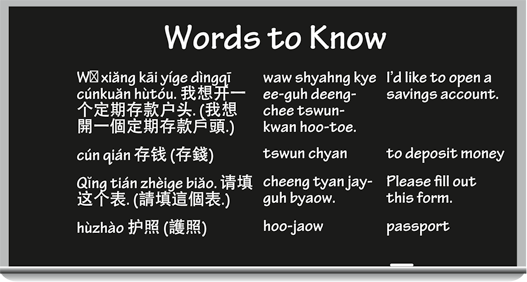

Doing Your Banking

If you plan on staying in Asia for an extended time or you want to continue doing business with a Chinese company, you may want to open a huóqī zhànghù 活期账户 (活期賬戶) (hwaw-chee jahng-hoo) (checking account) where you can both cún qián 存钱 (存錢) (tswun chyan) (deposit money) and qǔ qián 取钱 (取錢) (chyew chyan) (withdraw money). If you stay long enough, you should open a dìngqī cúnkuǎn hùtóu 定期存款户头 (定期存款戶頭) (deeng-chee tswun-kwan hoo-toe) (savings account) so you can start earning some lìxí 利息 (lee-she) (interest). Sure beats stuffing large bills under your mattress for years.

How about trying to make your money work for you by investing in one of the following?

chǔxù cúnkuǎn 储蓄存款 (儲蓄存款) (choo-shyew tswun-kwan) (certificate of deposit/CD)

chǔxù cúnkuǎn 储蓄存款 (儲蓄存款) (choo-shyew tswun-kwan) (certificate of deposit/CD)

guókù quàn 国库券 (國庫券) (gwaw-koo chwan) (treasury bond)

guókù quàn 国库券 (國庫券) (gwaw-koo chwan) (treasury bond)

gǔpiào 股票 (goo-pyaow) (stock)

gǔpiào 股票 (goo-pyaow) (stock)

hùzhù jījīn 互助基金 (hoo-joo jee-jeen) (mutual fund)

hùzhù jījīn 互助基金 (hoo-joo jee-jeen) (mutual fund)

tàotóu jījīn 套头基金 (套頭基金) (taow-toe jee-jeen) (hedge fund)

tàotóu jījīn 套头基金 (套頭基金) (taow-toe jee-jeen) (hedge fund)

zhàiquàn 债券 (債券) (jye-chwan) (bond)

zhàiquàn 债券 (債券) (jye-chwan) (bond)

Making withdrawals and deposits

Whether you need to cún qián 存钱 (存錢) (tswun chyan) (deposit money) or qǔ qián 取钱 (取錢) (chyew chyan) (withdraw money), you need to make sure you have enough qián in the first place to do so. One way to ensure you don’t overextend is to make sure you know what your jiéyú 结余 (結餘) (jyeh-yew) (account balance) is at any given moment. Sometimes you can check your available balance if you go online to see which checks may have already cleared. If someone gives you an yínháng běnpiào 银行本票 (銀行本票) (een-hahng bun-pyaow) (cashier’s check), however, it cashes immediately. Lucky you!

If you plan to cash some checks along with your deposits, here are a couple of useful phrases to know:

Wǒ yào duìxiàn zhèi zhāng zhīpiào. 我要兑现这张支票. (我要兌現這張支票. (waw yaow dway-shyan jay jahng jir-pyow.) (I’d like to cash this check.)

Wǒ yào duìxiàn zhèi zhāng zhīpiào. 我要兑现这张支票. (我要兌現這張支票. (waw yaow dway-shyan jay jahng jir-pyow.) (I’d like to cash this check.)

Bèimiàn qiān zì xiě zài nǎr? 背面签字写在哪儿? (背面簽字寫在哪兒?) (bay-myan chyan dzuh shyeh dzye nar?) (Where shall I endorse it?)

Bèimiàn qiān zì xiě zài nǎr? 背面签字写在哪儿? (背面簽字寫在哪兒?) (bay-myan chyan dzuh shyeh dzye nar?) (Where shall I endorse it?)

Talkin’ the Talk

Freddie:

Nín hǎo. Wǒ xiǎng kāi yíge dìngqī cúnkuǎn hùtóu.

neen how. waw shyahng kye ee-guh deeng-chee tswun-kwan hoo-toe.

Hello. I’d like to open a savings account.

Teller:

Méiyǒu wèntí. Nín yào xiān cún duōshǎo qián?

mayo one-tee. neen yaow shyan tswun dwaw-shaow chyan?

No problem. How much would you like to deposit initially?

Freddie:

Wǒ yào cún yìbǎi kuài qián.

waw yaow tswun ee-bye kwye chyan.

I’d like to deposit $100.

Teller:

Hǎo. Qǐng tián zhèige biǎo. Wǒ yě xūyào kànkàn nínde hùzhào.

how. cheeng tyan jay-guh byaow. waw yeah shyew-yaow kahn-kahn neen-duh hoo-jaow.

Fine. Please fill out this form. I will also need to see your passport.

Accessing an ATM

One of the most convenient ways to access some quick cash is to go to the nearest zìdòng tíkuǎnjī 自动提款机 (自動提款機) (dzuh-doong tee-kwan-jee) (ATM). ATMs are truly ubiquitous these days. Wherever you turn, there they are, on every other street corner. Sometimes I wonder how we ever survived without them. (Same goes for the personal computer . . . but I digress.)

In order to use a zìdòng tíkuǎnjī, you need a zìdòng tíkuǎn kǎ 自动提款卡 (自動提款卡) (dzuh-doong tee-kwan kah) (ATM card) to find out your account balance or to deposit or withdraw money. And you definitely need to know your mìmǎ 密码 (密碼) (mee-mah) (PIN); otherwise, the zìdòng tíkuǎnjī is useless. Just remember: Make sure you don’t let anyone else know your mìmǎ. It’s a mìmì 秘密 (mee-mee) (secret).

Tips on Tipping

Usually in the United States, a 15-percent tip is customary at restaurants, and you often give a 10-percent tip to taxi drivers. Giving xiǎo fèi 小费 (小費) (shyaow-fay) (tips) is expected pretty much everywhere from here to Timbuktu. In some instances, you should even give xiǎo fèi to people setting up towels in the public bathroom. Better to know in advance of your trip how much (or how little) is expected of you so you don’t embarrass yourself (and by extension, your countryfolk).

In Taiwan, xiǎo fèi are generally included in restaurant bills. If not, 10 percent is standard. You can gěi 给 (給) (gay) (give) bellboys and porters a dollar (USD) per bag.

In Taiwan, xiǎo fèi are generally included in restaurant bills. If not, 10 percent is standard. You can gěi 给 (給) (gay) (give) bellboys and porters a dollar (USD) per bag.

In Hong Kong, most restaurants automatically include a 10-percent tip, but feel free to give an additional 5 percent if the fúwù 服务 (服務) (foo-woo) (service) is good. Small tips are also okay for taxi drivers, bellboys, and washroom attendants.

In Hong Kong, most restaurants automatically include a 10-percent tip, but feel free to give an additional 5 percent if the fúwù 服务 (服務) (foo-woo) (service) is good. Small tips are also okay for taxi drivers, bellboys, and washroom attendants.

Tipping in mainland China used to be rare, but the idea is finally catching on, especially now that service with a scowl rather than a smile is fast becoming a thing of the past. (For the longest time, workers simply had no incentive to work harder or with a more pleasant demeanor after the Cultural Revolution. Can you blame workers for having no reason to perform their duties with the idea of customer service in mind?) A 3-percent tip is standard in restaurants (still low compared to Taiwan and Hong Kong). Bellboys and room service attendants typically expect a dollar or two (USD). Tipping in U.S. currency is still very much appreciated, because it’s worth about six times as much as the Chinese dollar.

Tipping in mainland China used to be rare, but the idea is finally catching on, especially now that service with a scowl rather than a smile is fast becoming a thing of the past. (For the longest time, workers simply had no incentive to work harder or with a more pleasant demeanor after the Cultural Revolution. Can you blame workers for having no reason to perform their duties with the idea of customer service in mind?) A 3-percent tip is standard in restaurants (still low compared to Taiwan and Hong Kong). Bellboys and room service attendants typically expect a dollar or two (USD). Tipping in U.S. currency is still very much appreciated, because it’s worth about six times as much as the Chinese dollar.

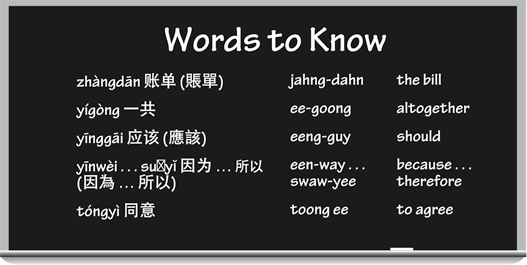

If you get a bill and can’t make heads or tails of it, you can always ask the following question to find out whether the tip is included:

Zhàngdān bāokuò fúwùfēi ma? 账单包括服务费吗? (賬單包括服務費嗎?) (jahng-dahn baow-kwaw foo-woo-fay mah?) (Does the bill include a service charge/tip?)

bǎifēn zhī bǎi 百分之百 (bye-fun jir bye) (100 percent [Literally: 100 out of 100 parts])

bǎifēn zhī bāshíwǔ 百分之八十五 (bye-fun jir bah-shir-woo) (85 percent [Literally: 85 out of 100 parts])

bǎifēn zhī shíwǔ 百分之十五 (bye-fun jir shir-woo) (15 percent [Literally: 15 out of 100 parts])

bǎifēn zhī sān 百分之三 (bye-fun jir sahn) (3 percent [Literally: 3 out of 100 parts])

bǎifēn zhī líng diǎn sān 百分之零点三 (百分只零點三) (bye-fun jir leeng dyan sahn) (0.3 percent [Literally: 0.3 out of 100 parts])

For more information on numbers, head to Chapter 5.

Talkin’ the Talk

Ben and Erin are in a restaurant. They get their bill and discuss how much of a tip to leave.

Erin:

Wǒmen de zhàngdān yígòng sānshí kuài qián. Xiǎo fèi yīnggāi duōshǎo?

waw-men duh jahng-dahn ee-goong sahn-shir kwye chyan. shyaow fay eeng-guy dwaw-shaow?

Our bill comes to $30 altogether. How much should the tip be?

Ben:

Yīnwèi fúwù hěn hǎo, suǒyǐ xiǎo fèi kěyǐ bǎifēn zhī èr shí. Nǐ tóngyì ma?

een-way foo-woo hun how, swaw-yee shyaow fay kuh-yee bai-fun jir are shir. nee toong-ee mah?

Because the service was really good, I think we can leave a 20-percent tip. Do you agree?

Erin:

Tóngyì.

toong-ee.

I agree.

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

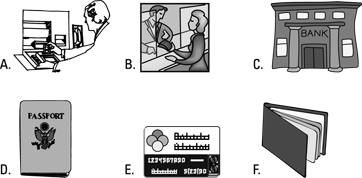

Identify what the following illustrations depict in Chinese. See Appendix D for the correct answers.

A. ______________

B. ______________

C. ______________

D. ______________

E. ______________

F. ______________

In addition to saying you have

In addition to saying you have

Overseas, many places accept American Express. Closer to America, businesses may only accept MasterCard or Visa. In some out-of-the-way parts of China, you can’t use plastic at all, so have plenty of cash or traveler’s checks on hand, just in case.

Overseas, many places accept American Express. Closer to America, businesses may only accept MasterCard or Visa. In some out-of-the-way parts of China, you can’t use plastic at all, so have plenty of cash or traveler’s checks on hand, just in case. The basic elements of all Chinese currency are the

The basic elements of all Chinese currency are the