Chapter 19

Handling Emergencies

In This Chapter

Yelling for help

Yelling for help

Visiting your doctor

Visiting your doctor

Going to the authorities

Going to the authorities

Looking for legal advice

Looking for legal advice

You can easily plan the fun and exciting things you want to experience while you travel or go out with friends, but you can’t predict needing to call the police to report a theft or rushing to an emergency room with lánmò yán 阑尾炎 (闌尾炎) (lahn-maw yeahn) (appendicitis) on your trip to the Great Wall. Such things can and do happen, and this chapter gives you the language tools you need to communicate your problems during your times of need.

Calling for Help in Times of Need

When you’re faced with an emergency, the last way you want to spend your time is searching for an oversized Chinese-English dictionary to figure out how to quickly call for help. Try memorizing these phrases before a situation arises:

Jiào jǐngchá! 叫警察 (jyaow jeeng-chah!) (Call the police!)

Jiào jǐngchá! 叫警察 (jyaow jeeng-chah!) (Call the police!)

Jiào jiùhùchē! 叫救护车! (叫救護車! (jyaow jyo-hoo-chuh!) (Call an ambulance!)

Jiào jiùhùchē! 叫救护车! (叫救護車! (jyaow jyo-hoo-chuh!) (Call an ambulance!)

Jiù mìng! 救命! (jyo meeng!) (Help!/Save me!)

Jiù mìng! 救命! (jyo meeng!) (Help!/Save me!)

Zháohuǒ lā! 着火啦! (jaow-hwaw lah!) (Fire!)

Zháohuǒ lā! 着火啦! (jaow-hwaw lah!) (Fire!)

Zhuā zéi! 抓贼 (抓賊!) (jwah dzay!) (Stop, thief!)

Zhuā zéi! 抓贼 (抓賊!) (jwah dzay!) (Stop, thief!)

Sometimes you have to ask for someone who speaks English. Here are some phrases you can quickly blurt out during emergencies:

Nǐ shuō Yīngwén ma? 你说英文吗? (你說英文嗎?) (nee shwaw eeng-one mah?) (Do you speak English?)

Nǐ shuō Yīngwén ma? 你说英文吗? (你說英文嗎?) (nee shwaw eeng-one mah?) (Do you speak English?)

Wǒ xūyào yíge jiǎng Yīngwén de lǜshī. 我需要一个讲英文的律师. (我需要一個講英文的律師.) (waw shyew-yaow ee-guh jyahng eeng-one duh lyew-shir.) (I need a lawyer who speaks English.)

Wǒ xūyào yíge jiǎng Yīngwén de lǜshī. 我需要一个讲英文的律师. (我需要一個講英文的律師.) (waw shyew-yaow ee-guh jyahng eeng-one duh lyew-shir.) (I need a lawyer who speaks English.)

Yǒu méiyǒu jiǎng Yīngwén de dàifu? 有没有讲英文的大夫? (有沒有講英文的大夫? (yo mayo jyahng eeng-one duh dye-foo?) (Are there any English-speaking doctors?)

Yǒu méiyǒu jiǎng Yīngwén de dàifu? 有没有讲英文的大夫? (有沒有講英文的大夫? (yo mayo jyahng eeng-one duh dye-foo?) (Are there any English-speaking doctors?)

When you finally get someone on the line who can help you, you need to know what to say to get immediate help:

Wǒ bèi rén qiǎng le. 我被人抢了. (我被人搶了.) (waw bay run chyahng luh.) (I’ve been robbed.)

Wǒ bèi rén qiǎng le. 我被人抢了. (我被人搶了.) (waw bay run chyahng luh.) (I’ve been robbed.)

Wǒ yào huì bào yíge chē huò. 我要汇报一个车祸. (我要匯報一個車禍.) (waw yaow hway baow yee-guh chuh hwaw.) (I’d like to report a car accident.)

Wǒ yào huì bào yíge chē huò. 我要汇报一个车祸. (我要匯報一個車禍.) (waw yaow hway baow yee-guh chuh hwaw.) (I’d like to report a car accident.)

Yǒu rén shòu shāng le. 有人受伤了. (有人受傷了.) (yo run show shahng luh.) (People are injured.)

Yǒu rén shòu shāng le. 有人受伤了. (有人受傷了.) (yo run show shahng luh.) (People are injured.)

Receiving Medical Care

It’s everyone’s greatest nightmare — getting sick and not knowing why or how to make it better. If you suddenly find yourself in the yīyuàn 医院 (醫院) (ee-ywan) (hospital) or otherwise visiting an yīshēng 医生 (醫生) (ee-shung) (doctor), you need to explain what ails you — often in a hurry. Doing so may be easier said than done, especially if you have to explain yourself in Chinese (or help a Chinese-speaking victim who’s having trouble communicating), but don’t worry. In the following sections, I walk you through your doctor’s visit step by step.

Unless you’re in a big city like Beijing or Shanghai, if you get seriously ill while staying in mainland China, your best bet is to fly to Hong Kong or back home for medical care. Don’t forget to check into evacuation insurance before you go.

Unless you’re in a big city like Beijing or Shanghai, if you get seriously ill while staying in mainland China, your best bet is to fly to Hong Kong or back home for medical care. Don’t forget to check into evacuation insurance before you go.

Warning: Chinese people don’t have O-negative blood, so Chinese hospitals don’t store it. If you have a medical emergency in China that requires O-negative blood, you should check directly with your country’s nearest embassy or consulate for help. You may need to be airlifted out to get the appropriate care. You may also want to take your own hypodermic needles in case you need an injection because you can’t guarantee that the needles you may come across are sterilized. Better safe than sorry away from home.

Warning: Chinese people don’t have O-negative blood, so Chinese hospitals don’t store it. If you have a medical emergency in China that requires O-negative blood, you should check directly with your country’s nearest embassy or consulate for help. You may need to be airlifted out to get the appropriate care. You may also want to take your own hypodermic needles in case you need an injection because you can’t guarantee that the needles you may come across are sterilized. Better safe than sorry away from home.

Deciding whether to see a doctor

If your luck is good, you’ll never need to use any of the phrases I present in this chapter. If you end up running out of luck, however, keep reading. Even if you’ve never smoked a day in your life, you can still develop a cough or even bronchitis. Time to see a yīshēng.

Talkin’ the Talk

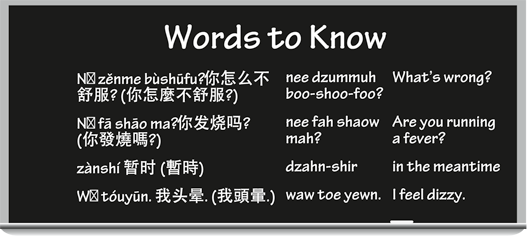

Dàlín and his wife, Miǎn, are on their first trip back to China in 20 years. Miǎn becomes concerned about a sudden onset of dizziness. The two discuss her symptoms.

Dàlín:

Nǐ zěnme bùshūfu?

nee dzummuh boo-shoo-foo?

What’s wrong?

Miǎn:

Wǒ gǎnjué bùshūfu kěshì bù zhīdào wǒ déle shénme bìng.

waw gahn-jweh boo-shoo-foo kuh-shir boo jir-daow waw duh-luh shummuh beeng.

I don’t feel well, but I don’t know what I have.

Dàlín:

Nǐ fā shāo ma?

nee fah shaow mah?

Are you running a fever?

Miǎn:

Méiyǒu, dànshì wǒ tóuyūn. Yěxǚ wǒ xūyào kàn nèikē yīshēng.

mayo, dahn-shir waw toe-yewn. yeh-shyew waw shyew-yaow kahn nay-kuh ee-shung.

No, but I feel dizzy. Perhaps I need to see an internist.

Dàlín calls the nearest medical clinic to make an appointment and then returns to Miǎn.

Dàlín:

Wǒ jīntiān xiàwǚ sān diǎn zhōng yuē le yíge shíjiān. Nǐ zuì hǎo zànshí zuò xiàlái.

waw jin-tyan shyah-woo sahn dyan joong yweh luh ee-guh shir-jyan. nee dzway how dzahn-shir dzwaw shyah-lye.

I’ve made an appointment for 3:00 this afternoon. In the meantime, you’d better sit down for a while.

Describing what ails you

First things first: You can’t tell the doctor where it hurts if you don’t know the word for what hurts. (Sure, you can point, I guess, but that only goes so far; when was the last time you tried pointing to internal organs?) Table 19-1 spells out the general body parts.

Table 19-1 Basic Body Words

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

tóu 头 (頭) |

toe |

head |

|

ěrduō 耳朵 |

are-dwaw |

ear |

|

liǎn 脸 (臉) |

lyan |

face |

|

yǎnjīng 眼睛 |

yan-jeeng |

eye |

|

bízi 鼻子 |

bee-dzuh |

nose |

|

bózi 脖子 |

baw-dzuh |

neck |

|

hóulóng 喉咙 (喉嚨) |

ho-loong |

throat |

|

jiānbǎng 肩膀 |

jyan-bahng |

shoulder |

|

gēbo 胳膊 |

guh-baw |

arm |

|

shǒu 手 |

show |

hand |

|

shǒuzhǐ 手指 |

show-jir |

finger |

|

xiōng 胸 |

shyoong |

chest |

|

fèi 肺 |

fay |

lungs |

|

xīn 心 |

shin |

heart |

|

dùzi 肚子 |

doo-dzuh |

stomach |

|

gān 肝 |

gahn |

liver |

|

shèn 肾 |

shun |

kidney |

|

bèi 背 |

bay |

back |

|

tuǐ 腿 |

tway |

leg |

|

jiǎo 脚 (腳) |

jyaow |

foot |

|

jiǎozhǐ 脚趾 (腳趾) |

jyaow-jir |

toe |

|

shēntǐ 身体 (身體) |

shun-tee |

body |

|

gǔtóu 骨头 (骨頭) |

goo-toe |

bone |

|

jīròu 肌肉 |

jee-row |

muscles |

|

shénjīng 神经 (神經) |

shun-jeeng |

nerves |

Maybe you’re just now checking your old wēndùjì 温度计 (溫度計) (one-doo-jee) (thermometer) and finding out Wǒ fā shāo le! 我发烧了! (我發燒了!) (waw fah shaow luh) (I have a fever!) Time to figure out what the problem is. Whether you make a sudden trip to the jízhěnshì 急诊室 (急診室) (jee-jun-shir) (emergency room) or take a normal visit to a private doctor’s office, you’ll probably field the same basic questions about your symptoms. Table 19-2 lists some symptoms you may have.

Table 19-2 Common Medical Symptoms

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

bèi tòng 背痛 |

bay toong |

backache |

|

biànmì 便秘 |

byan-mee |

constipation |

|

ěr tòng 耳痛 |

are toong |

earache |

|

ěxīn 恶心 (噁心) |

uh-sheen |

nauseous |

|

fāshāo 发烧 (發燒) |

fah-shaow |

to have a fever |

|

hóulóng téng 喉咙痛 (喉嚨痛) |

ho-loong tung |

sore throat |

|

lādùzi 拉肚子 |

lah-doo-dzuh |

diarrhea |

|

pàngle 胖了 |

pahng-luh |

to put on weight |

|

shòule 瘦了 |

show-luh |

to lose weight |

|

tóuténg 头疼 (頭疼) |

toe-tung |

headache |

|

wèi tòng 胃痛 |

way toong |

stomachache |

|

xiàntǐ zhǒngle 腺体肿了 (腺體腫了) |

shyan-tee joong-luh |

swollen glands |

|

yá tòng 牙痛 |

yah toong |

toothache |

In an emergency, you may not have the energy to remember both the pronunciation and the proper tone for the word you mean to use. You may want to say you’re feeling kind of tóuyūn 头晕 (頭暈) (toe-yewn) (dizzy), but if it comes out sounding like tuōyùn 托运 (托運) (twaw-yewn) instead, you alert your caregiver that you’re sending your luggage on ahead of you.

Talkin’ the Talk

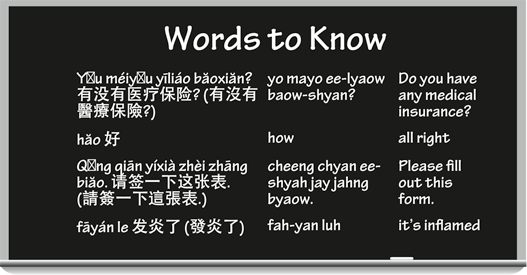

Jiēdàiyuán:

Nǐ shì lái kànbìng de ma?

nee shir lye kahn-beeng duh mah?

Have you come to see a doctor?

Kristen:

Shì de.

shir duh.

Yes.

Jiēdàiyuán:

Yǒu méiyǒu yīliáo bǎoxiǎn?

yo mayo ee-lyaow baow-shyan?

Do you have any medical insurance?

Kristen:

Yǒu.

yo.

Yes, I do.

Jiēdàiyuán:

Hǎo. Qǐng qiān yíxià zhèi zhāng biǎo.

how. cheeng chyan ee-shyah jay jahng byaow.

All right. Please fill out this form.

A short while later, the receptionist introduces Kristen to a hùshì (hoo-shir) (nurse), who plans to take her blood pressure.

Jiēdàiyuán:

Hùshì huì xiān liáng yíxià xuèyā.

hoo-shir hway shyan lyahng ee-shyah shweh-yah.

The nurse will first take your blood pressure.

Hùshì:

Qǐng juǎnqǐ nǐde xiùzi.

cheeng jwan-chee nee-duh shyo-dzuh.

Please roll up your sleeve.

Hùshì:

Hǎo. Huò Dàifu xiànzài gěi nǐ kànbìng.

how. hwaw dye-foo shyan-dzye gay nee kahn-beeng.

All right. Dr. Huo will see you now.

Kristen enters Dr. Huo’s office, and after a few basic introductory questions, Dr. Huo asks her what brings her to his office.

Huò Dàifu:

Yǒu shénme zhèngzhuàng?

yo shummuh juhng-jwahng?

What sorts of symptoms do you have?

Kristen:

Wǒde hóulóng cóng zuótiān jiù tòngle.

waw-duh ho-loong tsoong dzwaw-tyan jyo toong-luh.

I’ve had this pain in my throat since yesterday.

Huò Dàifu:

Hǎo. Wǒ xiān yòng tīngzhěnqì tīng yíxià nǐde xīnzàng.

how. waw shyan yoong teeng-jun-chee teeng ee-shyah nee-duh shin-dzahng.

All right. I’m first going to use a stethoscope to listen to your heart.

Dr. Huo puts the stethoscope to Kristen’s chest.

Huò Dàifu:

Shēn hūxī.

shun hoo-she.

Take a deep breath.

Dr. Huo finishes listening with the stethoscope and takes out a tongue depressor.

Huò Dàifu:

Qǐng bǎ zuǐ zhāngkāi, bǎ shétóu shēn chūlái . . . duì le. Nǐde hóulóng hǎoxiàng yǒu yìdiǎn fāyán.

cheeng bah dzway jahng-kye, bah shuh-to shun choo-lye . . . dway luh. nee-duh ho-loong how-shyahng yo ee-dyan fah-yan.

Please open your mouth and stick out your tongue . . . yes. Your throat seems to be inflamed.

Discussing your medical history

When you see a doctor for the first time, he or she will want to find out about your bìng lì 病历 (病歷) (beeng lee) (medical history). You’ll hear the following query: Nǐ jiā yǒu méiyǒu _____ de bìnglì? 你家有没有 _____ 的病历? (你家有沒有 _____ 的病歷?) (nee jyah yo mayo _____ duh beeng-lee?) (Does your family have any history of _____?)

Table 19-3 lists some of the more serious illnesses that hopefully neither you nor your family members have ever had.

Table 19-3 Serious Illnesses

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

áizhèng 癌症 |

eye-juhng |

cancer |

|

àizǐbìng 艾滋病 |

eye-dzuh-beeng |

AIDS |

|

bǐngxíng gānyán 丙型肝炎 |

beeng-sheeng gahn-yan |

hepatitis C |

|

fèi’ái 肺癌 |

fay-eye |

lung cancer |

|

fèi jiéhé 肺结核 (肺結核) |

fay jyeh-huh |

tuberculosis |

|

huòluàn 霍乱 (霍亂) |

hwaw-lwan |

cholera |

|

jiǎxíng gānyán 甲型肝炎 |

jya-sheeng gahn-yan |

hepatitis A |

|

lìjí 痢疾 |

lee-jee |

dysentery |

|

qìchuǎnbìng 气喘病 (氣喘病) |

chee-chwan-beeng |

asthma |

|

shuǐ dòu 水痘 |

shway-doe |

chicken pox |

|

tángniàobìng 糖尿病 |

tahng-nyaow-beeng |

diabetes |

|

xīnzàng yǒu máobìng 心脏有 毛病 (心臟有毛病) |

shin-dzahng yo maow-beeng |

heart trouble |

|

yǐxíng gānyán 已型肝炎 |

ee-sheeng gahn-yan |

hepatitis B |

Making a diagnosis

Did your doctor say those magic words: Méi shénme 没什么 (沒甚麼) (may shummuh) (It’s nothing)? Yeah, neither did mine. Too bad. I bet you’ve heard stories about how doctors who use traditional medical techniques from ancient cultures can just take one look at a person and immediately know what ails them. The truth is, aside from simple colds and the flu, most doctors still need to take all kinds of tests to give a proper diagnosis. They may even need to perform the following tasks:

huà yàn 化验 (化驗) (hwah yan) (lab tests)

huà yàn 化验 (化驗) (hwah yan) (lab tests)

xīndiàntú 心电图 (心電圖) (shin-dyan-too) (electrocardiogram)

xīndiàntú 心电图 (心電圖) (shin-dyan-too) (electrocardiogram)

huàyàn yíxià xiǎobiàn 化验一下小便 (化驗一下小便) (hwah-yan ee-shyah shyaow-byan) (have your urine tested)

huàyàn yíxià xiǎobiàn 化验一下小便 (化驗一下小便) (hwah-yan ee-shyah shyaow-byan) (have your urine tested)

When the doctor is ready to give you the verdict, here are some of the conditions you may hear (the minor ones, at least; check out Table 19-3 for more serious diagnoses):

bìngdú 病毒 (beeng-doo) (virus)

bìngdú 病毒 (beeng-doo) (virus)

gǎnmào 感冒 (gahn-maow) (a cold)

gǎnmào 感冒 (gahn-maow) (a cold)

gǎnrǎn 感染 (gahn-rahn) (infection)

gǎnrǎn 感染 (gahn-rahn) (infection)

guòmín 过敏 (過敏) (gwaw-meen) (allergies)

guòmín 过敏 (過敏) (gwaw-meen) (allergies)

liúgǎn 流感 (lyo-gahn) (flu)

liúgǎn 流感 (lyo-gahn) (flu)

qìguǎnyán 气管炎 (氣管炎) (chee-gwahn-yan) (bronchitis)

qìguǎnyán 气管炎 (氣管炎) (chee-gwahn-yan) (bronchitis)

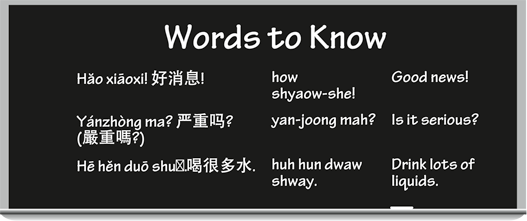

Talkin’ the Talk

Yīshēng:

Lauren, hǎo xiāoxi! Nǐde tǐwēn zhèngcháng.

Lauren, how shyaow-she! nee-duh tee-one juhng-chahng.

Lauren, good news! Your temperature is normal.

Lauren:

Hǎo jí le.

how jee luh.

Great.

Yīshēng:

Kěnéng zhǐ shì gǎnmào.

kuh-nung jir shir gahn-maow.

Perhaps it’s just a little cold.

Pete:

Hái chuánrǎn ma?

hi chwahn-rahn mah?

Is it still contagious?

Yīshēng:

Bú huì.

boo hway.

No.

Lauren:

Yánzhòng ma?

yan-joong mah?

Is it serious?

Yīshēng:

Bù yánzhòng. Nǐ zuì hǎo xiūxi jǐ tiān hē hěn duō shuǐ, jiù hǎo le.

boo yan-joong. nee dzway how shyow-she jee tyan huh hun dwaw shway, jyo how luh.

No. You should rest for a few days and drink lots of liquids, and it should get better.

Pete:

Tā děi zài chuángshàng tǎng duōjiû?

tah day dzye chwahng-shahng tahng dwaw-jyo?

How long must she rest in bed?

Yīshēng:

Zuì hǎo liǎng sān tiān.

dzway how lyahng sahn tyan.

Ideally for two or three days.

Treating yourself to better health

Not everything can be cured with a bowl of jī tāng 鸡汤 (雞湯) (jee tahng) (chicken soup), despite what my grandmother told me. If your grandmother cooks as well as mine did, however, the soup couldn’t hurt . . .

Your doctor may prescribe some yào 药 (藥) (yaow) (medicine) to make you feel better. After you tián 填 (填) (tyan) (fill) your yīliào chǔ fāng 医疗处方 (醫療處方) (ee-lyaow choo fahng) (prescription), you may find the following instructions on the bottle:

Fàn hòu chī. 饭后吃. (飯後吃.) (fahn ho chir.) (Take after eating.)

Fàn hòu chī. 饭后吃. (飯後吃.) (fahn ho chir.) (Take after eating.)

Měi sìge xiǎoshí chī yícì. 每四个小时吃一次. (每四個小時吃一次.) (may suh-guh shyaow-shir chir ee-tsuh.) (Take one tablet every four hours.)

Měi sìge xiǎoshí chī yícì. 每四个小时吃一次. (每四個小時吃一次.) (may suh-guh shyaow-shir chir ee-tsuh.) (Take one tablet every four hours.)

Měi tiān chī liǎng cì, měi cì sān piàn. 每天吃两次, 每次三片. (每天吃兩次, 每次三片.) (may tyan chir lyahng tsuh, may tsuh sahn pyan.) (Take three tablets twice a day.)

Měi tiān chī liǎng cì, měi cì sān piàn. 每天吃两次, 每次三片. (每天吃兩次, 每次三片.) (may tyan chir lyahng tsuh, may tsuh sahn pyan.) (Take three tablets twice a day.)

Calling the Police

Ever have your pocketbook tōu le (toe luh) (stolen)? Being a victim is an awful feeling, as I can tell you from experience. You feel angry at such a scary experience, especially if it happens in another country and the zéi 贼 (賊) (dzay) (thief) táopǎo 逃跑 (taow-paow) (escapes) quickly.

I hope you’re never the victim of a crime like theft (or something worse). Still, you should always be prepared with some key words you can use when the jǐngchá 警察 (jeeng-chah) (police) finally pull up in the jǐngchē 警车 (警車) (jeeng-chuh) (police car) and take you back to the jǐngchájú 警察局 (jeeng-chah-jyew) (police station) to identify a potential zéi. Hopefully the culprit will be zhuā le 抓了 (jwah luh) (arrested).

You may also find yourself in an emergency that doesn’t involve you. If you ever witness an accident, here are some phrases you can relay to the police, emergency workers, or victims:

Bié kū. Jǐngchá hé jiùhùchē láile. 别哭. 警察和救护车来了. (別哭. 警察和救護車來了.) (byeh koo. jeeng-chah huh jyo-hoo-chuh lye-luh.) (Don’t cry. The police and the ambulance have arrived.)

Bié kū. Jǐngchá hé jiùhùchē láile. 别哭. 警察和救护车来了. (別哭. 警察和救護車來了.) (byeh koo. jeeng-chah huh jyo-hoo-chuh lye-luh.) (Don’t cry. The police and the ambulance have arrived.)

Tā bèi qìchē yàzháo le. 他被车压着了. (他被車压着了.) (tah bay chee-chuh yah-jaow luh.) (He was run over by a car.)

Tā bèi qìchē yàzháo le. 他被车压着了. (他被車压着了.) (tah bay chee-chuh yah-jaow luh.) (He was run over by a car.)

Tā zài liúxiě. 他在流血. (tah dzye lyo-shyeh.) (He’s bleeding.)

Tā zài liúxiě. 他在流血. (tah dzye lyo-shyeh.) (He’s bleeding.)

Acquiring Legal Help

Nine out of ten foreigners never need to look for a lawyer during a stay in China, which isn’t as litigious a society as the United States, to be sure. If you do need a lǜshī 律师 (律師) (lyew-shir) (lawyer), however, your best bet is to check with your country’s dàshǐguǎn 大使馆 (大使館) (dah-shir-gwahn) (embassy) or língshìguǎn 领事馆 (領事館) (leeng-shir-gwahn) (consulate) for advice.

It can be very annoying and stressful to have to deal with lǜshī, no matter what country you’re in, but you have to admit — they do know the fǎlǜ 法律 (fah-lyew) (law). And if you have to go to fǎyuàn 法院 (fah-ywan) (court) for any serious incident, you want the judge to pànjué 判决 (判決) (pahn-jweh) (make a decision) in your favor. Moral of the story: Good lǜshī are worth their weight in gold, even if you still consider them sharks in the end.

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Identify the following body parts in Chinese. Check Appendix D for the answers.

1. Arm: ______________

2. Shoulder: ______________

3. Finger: ______________

4. Leg: ______________

5. Neck: ______________

6. Chest: ______________

7. Eye: ______________

8. Ear: ______________

9. Nose: ______________

Here are a couple of additional medical-emergency tips for traveling in China:

Here are a couple of additional medical-emergency tips for traveling in China: Although verbs don’t express tense in Chinese, you often connect them to things called

Although verbs don’t express tense in Chinese, you often connect them to things called