By September 20, British troops were still camped near Valley Forge as Gen. Howe, again mirroring Washington’s instincts, contemplated a thrust west to meet the Continental Army. In the meantime, Gen. Wayne’s Pennsylvania division had crept to within three miles of the enemy lines, perilously close to within long cannon shot and near enough to hear the British drummers beat reveille. Wayne had bivouacked his 2,000 or so regulars on the edge of a copse along a plateaued rise near a tavern perhaps regrettably named for the Corsican revolutionary Gen. Pasquale Paoli. Paoli, once popular in America for his attempts to drive the French colonizers from his island, was at present the latest celebrity-in-exile gracing London’s salons. No one thought to change the name of the tavern. Wayne was still waiting for Gen. Smallwood’s Maryland reinforcements and what he hoped would be orders from Washington to attack. He assumed, wrongly, that the presence of his own troops had been undetected by the British.

Journals and diaries kept by soldiers from both sides describe an ominous cloud cover rolling over the area late that Saturday afternoon, and by nightfall completely obscuring the full moon and stars. Wayne was aware of his precarious position; his original plan was to move out under cover of darkness. But with Gen. Smallwood and his militiamen inexplicably delayed and the scent of another heavy rain in the air, he instead instructed his men to fashion a series of what the Continentals called “weather booths”—primitive lean-tos constructed of tree branches, thick cornstalks, and trimmed saplings that would keep dry both the soldiers and the little powder they were carrying. As his troops went to work on their improvised huts Wayne and a small group of aides rode off to reconnoiter their perimeter.

This was familiar and, for the most part, friendly territory for the young general. Wayne—the grandson of Anglo-Irish immigrants who had been the recipients of an extensive royal land grant in what was to become Chester County—had been born only a few miles away. Prior to the revolution he had established himself as a successful farmer, state politician, and surveyor—he’d once laid out plans for a settlement on land in Nova Scotia owned by Benjamin Franklin and a consortium of merchants—and when war broke out he’d raised a regiment of Pennsylvania militiamen. Although he had no formal military training, what one historian calls his “zeal and spunk” soon led to his appointment as a colonel in the Continental Army.

Wayne and his Pennsylvanians had subsequently distinguished themselves during the failed invasion of Canada, where Wayne was wounded during the Battle of Three Rivers. Wayne’s natural athleticism belied his vicar’s visage, and his boundless energy and fighting skills—what harder-eyed observers might describe as his reckless abandon—had caught Washington’s eye. Upon his recovery he was promoted to brigadier general in early 1777. Wayne’s mettle and knowledge of the territory had rewarded Washington’s judgment at Brandywine Creek, and if the American commander in chief trusted anyone to cover the local terrain while playing cat and mouse with a British force that outnumbered him seven to one, it was the lord of Waynesboro Manor.

Yet neither American took into account the possibility that the same Tories who had guided Howe across the upper branches of the Brandywine would inform the British of Wayne’s location. While Wayne was off on his scouting mission, Gen. Howe was quietly assembling some 2,000 elite British and Scottish raiders to fall on the Pennsylvanians. This light infantry, under the command of Gen. Charles Grey, was well versed in the swift, stealthy movements of ranger tactics. Before departing camp, Grey ordered most of his soldiers to remove the flints from their .75-caliber “kings arms”—the ubiquitous musket soon to be known around the world as the deadly “Brown Bess.” It was fitting that Grey, a small, thin officer with a face as pinched as a hatchet, so resembled a metal instrument of destruction; the night attack he had been chosen to lead was to be purely a bayonet assault.

The British bayonets were triangular in shape, ensuring that even if the 18-inch blade did not puncture a vital organ, at least one facet of the weapon would always be slicing near a heart, a kidney, a liver. Moreover, the tips of the bayonets were not sharpened but blunt, cast to tear at an opponent’s flesh like a shark’s tooth instead of inflicting a surgical cut that could be easily sutured. It was a perfectly deadly tactic for a dark, rainy night. As Grey’s second in command, Capt. John André, confided to his journal: “It was represented to the men that firing discovered us to the Enemy, hid them from us, killed our friends and produced a confusion favorable to the escape of the Rebels and perhaps productive of disgrace to ourselves. On the other hand, by not firing we knew the foe to be wherever fire appeared and a [bayonet] charge ensured his destruction; that amongst the enemy those in the rear would direct their fire against whoever fired in front, and they would destroy each other.”

Although Wayne had dashed off a communiqué to Washington the previous morning assuring his commander that Howe “knows nothing of my Situation—as I have taken every precaution to Prevent any intelligence getting to him,” there are indications that he had been warned by at least one local patriot that the enemy was aware of his camp. When he returned to his headquarters tent around 10 that night he took the precaution of increasing his picket posts from four to six, with each squad consisting of roughly 20 sentries. These included a mounted picket called a vidette.

With Smallwood yet to appear, Wayne was loath to break camp and complicate their rendezvous. Washington had indicated to Wayne that once his and Smallwood’s troops were combined, they would make up one half of the pincer movement buffeting Howe’s rear. The commander in chief’s much larger force, already on the move from Yellow Springs, would form the other half. So certain was Wayne of Smallwood’s imminent arrival that he instructed his company commanders to be prepared to move at the first sight of the Marylander’s forward scouts. As the Pennsylvanians waited, the British force under Grey was already on the march beneath the starless sky.

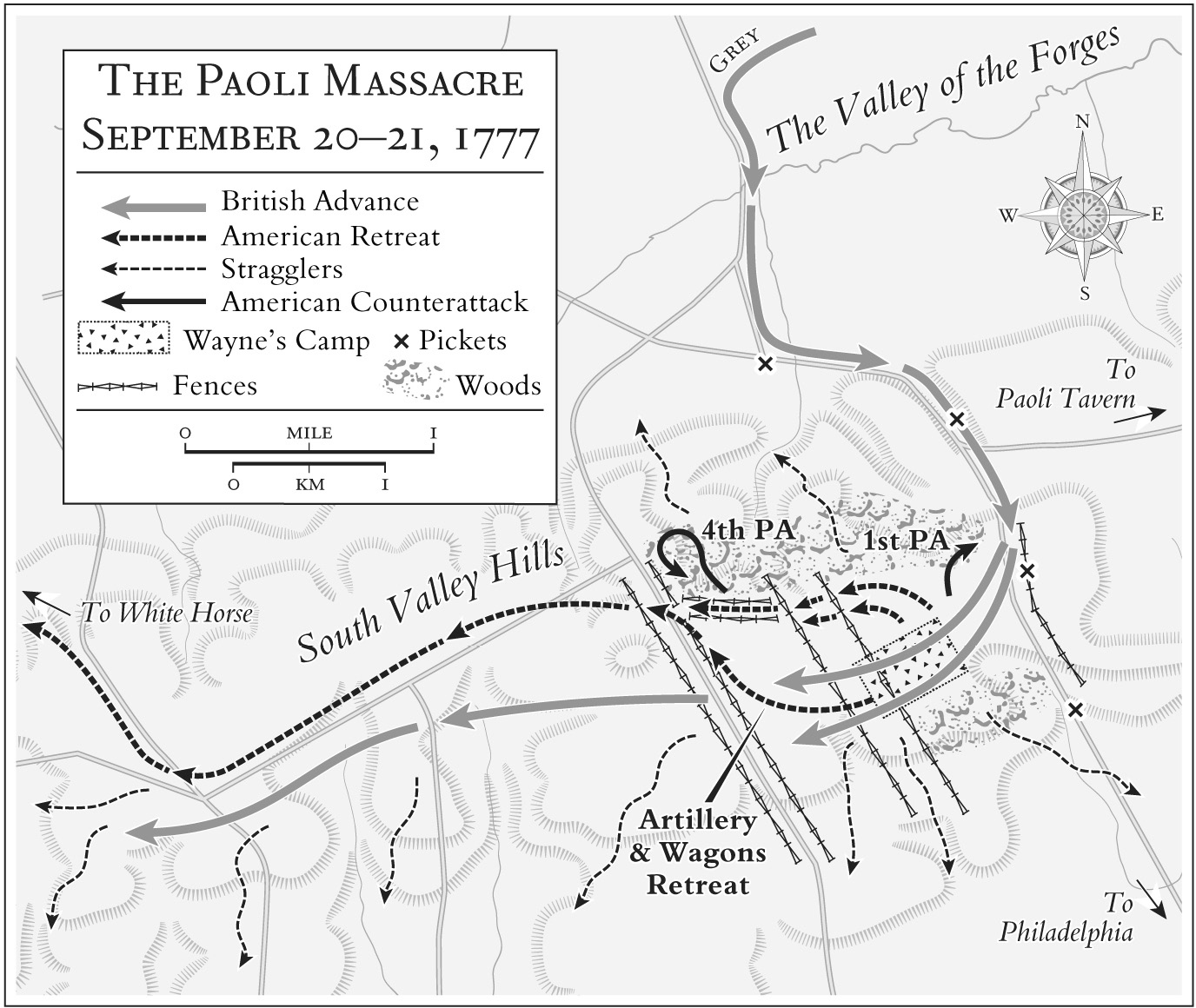

Guided through the murk by an American deserter and a local blacksmith coerced into cooperation, Grey took no chance of tipping his prey and flanked out skirmishers to sweep up and detain every man, woman, and child in his path. Sometime before midnight a company of these advance guards was spotted by two of the American videttes, who fired on it before galloping back to camp with the alert. Wayne immediately ordered his entire division turned out to arms. He was too late. Moments later the Americans heard a volley of flintlock fire perhaps three quarters of a mile to the north. Then silence. They had no idea that one of their picket posts had been overrun by a bayonet charge. Wayne next issued orders to evacuate the camp, beginning with the two dozen wagons hauling his four field pieces, spare ammunition, and commissary and quartermaster supplies.

As the division filed into columns, the Continentals heard more gunfire to their northeast. It was a second, closer American picket getting off final musket shots before being cut to pieces. Moments later, on the cry of “Dash, Light Infantry!” the first battalion of 500 enemy troops poured into Wayne’s right flank. The Americans were overwhelmed. The campfires still burning beside the weather booths served as homing beacons for the wave of Redcoats who cut and slashed their way into the middle of the American camp, their blades flashing in the firelight. At such close range, musketeers had little chance against bayonets, particularly at night. Those who did manage to use their weapons in the mounting chaos proved Capt. André prescient. Panicked Americans pulled their triggers at any firelock flash they saw. The British had still not fired a shot.

Meanwhile, Wayne’s retreat across a fenced-in meadow stalled when one of the forward wagons hauling a field piece broke down and blocked the adjacent road. This was a perfect example of what the preeminent Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz referred to as “friction”—the unexpected and seemingly innocuous battlefield occurrence that sets off a string of unintended effects resulting in disaster. With the remainder of the wagon train now stalled, the rush of American foot soldiers attempting to shove past the obstruction between fences created a bottleneck for slaughter. A second wave of 350 British infantrymen, accompanied by a dozen or so of the Queen’s Own Light Dragoons atop snorting warhorses, saw to it. To shouts of “No Quarter” the enemy surrounded the jumbled body of Continentals and ran at them in flights of bayonet rushes. Any American who managed to escape the mayhem was run down by the mounted dragoons, who wielded their three-foot broadswords like scythes. Wayne and his company commanders were attempting to wheel the writhing mass of bleeding humanity into a semblance of a defensive line when another 300 British soldiers emerged from the woods behind them and charged.

The early evening’s light rain had grown thicker, and the battlefield, if it can be called such, was by now a soupy brew of mud, blood, and gore. The broken wagon was pushed off the road, and the Americans who made it out of camp now streamed west with the rush of a river current. The wounded were carried by comrades as best they could be, while the able-bodied left behind were beyond putting up any organized resistance. Hand-to-hand fighting was their only recourse. Eyewitnesses later testified that Continentals attempting to surrender were surrounded by as many as a dozen British infantrymen who took turns running them through with steel blades. A subsequent compilation of wounds to the dead would confirm this. For Gen. Grey, all that was left was to administer the coup de grâce. This was accomplished by what one chronicler of the fight called “the largest and most terrifying menace of the night.”

Grey had held in reserve two companies of the Royal Highlands Regiment, the ferocious Black Watch, for just this occasion. Now, at his signal, the nearly 600 Scotsmen in their short red jackets and tassled blue bonnets were released in a double-ranked battle line. They had adopted canvas “trews,” or trousers, in place of their traditional kilts. Savage Gaelic battle cries filled the air as the Scots swept across the killing field in a solid front without breaking ranks. They put to the bayonet any wounded or stragglers they encountered and began systematically burning the weather booths, often with frightened Americans still hiding inside. As Capt. André laconically observed, “We stabbed great numbers.”

While Gen. Wayne attempted to form yet another rear guard not far from where the artillery wagon had broken down, Gen. Smallwood and his 2,000 or so Maryland troops were finally approaching Paoli along the muddy, rutted roads leading east. Smallwood digested the reports of the fighting from the first retreating Pennsylvanians he met and decided to fall back about a mile to higher ground and form a defensive line behind which Wayne’s forces could regroup. He had done much the same 13 months earlier during the Battle of Long Island. Despite that engagement’s disastrous outcome, his rearguard action at Brooklyn Heights was credited with saving hundreds of American lives. Smallwood had barely issued the order to form up when his left flank was raked by a volley from a company of British light infantry chasing Wayne’s stragglers. Earlier, back at Howe’s camp, this particular group of infantrymen had been exempted from the order to remove their flints after their commander promised to hold himself personally responsible for any of his men who fired their weapons. Now they had expressly disobeyed the order not to fire.

This made little matter to many of Smallwood’s militiamen, who promptly fulfilled the French colonel Duportail’s grim forecast by flinging away their weapons, turning tail, and running like foxes before the hounds. Those who did not flee fired madly at anything that moved. General Smallwood himself narrowly escaped this friendly fire when a dragoon riding beside him was blown off his horse and killed by an American musket ball. Nearly half of the Maryland men vanished into the Pennsylvania countryside that night, never to be heard from again, before Smallwood’s officers finally regrouped the remainder to form a defensive line. There they waited for Wayne and the roiling cluster of his surviving regulars while bracing for the British and Scottish in pursuit.

Yet by this time the blare of trumpets had recalled the enemy troops back to the smoking, reeking scene of what can only be called a massacre. The overwhelming success of the operation stunned even the most presumptuous British officers. Of the 272 men reported missing from Wayne’s division, nearly 60 lay dead on and around the battlefield. Despite the unofficial “No Quarter” strategy, the British did manage to take some 71 American prisoners, more than half of them seriously wounded. They had also captured nine of the Continental supply wagons piled with food and baggage. Their own losses came to three dead, eight wounded, and two horses killed. By dawn they had returned to Howe’s camp near Valley Forge to ringing huzzahs.

♦ ♦ ♦

Washington had the ignominy of learning the results of the Battle of Paoli from the enemy himself. The next morning, before Wayne’s riders reached the commander in chief’s new camp across the Schuylkill, a British messenger forded the river offering a flag of truce to Continental burial details. General Howe, as he had at Brandywine, also allowed passage to surgeons to treat the most severely injured prisoners who had been deposited at local homes, inns, and taverns in British-controlled territory. The doctors were appalled at having to dress the multiple stab wounds, often a dozen or more per soldier. Many of the wounded would not see October.

Even by the standards of eighteenth-century combat, the unprofessionalism shown by the British who killed and maimed surrendering Continentals that night was scandalous and would blight the careers of the officers who led them, Gen. Grey in particular, who that night acquired the nickname “No Flint Grey.” It would even affix a taint of dishonor to Howe himself. The general’s defenders argued that a “No Quarter” order had never been given. Their proof—the 71 American prisoners in Crown hands. The same defenders conveniently elided the fact that nearly every American prisoner had been the victim of multiple bayonet wounds. For his part, Howe saw no point in adhering to the informal yet generally recognized European “laws of war” that prohibited the killing of wounded or unarmed soldiers. The American colonists—a mere “herd of fugitives,” according to Capt. André—were in rebellion, and thus traitors to the Crown not entitled to the presumptions of such established custom.

The Continentals naturally viewed the events in a different light. To their sensibility, the acts of butchery by the enemy that night, against unarmed men, could be expected of hired mercenaries, particularly the Germans contracted by George III to fight in North America. But the viciousness with which the English and Scottish had treated their erstwhile American “cousins” revealed a loathing for the rebels that seethed just below the surface throughout the revolution. It would not soon be forgotten, and “Remember Paoli” was to become an American battle cry long before the Alamo or the battleship USS Maine.

When an official American inquiry was convened to explore the roots of the “Paoli Massacre,” some were inclined to charge Gen. Wayne with gross misconduct. Instead, the court of inquiry found him guilty of only tactical errors centered on his failure to decamp earlier. He was nonetheless outraged at even this minor rebuke, and as was becoming more common among the fragile egos of the Continental Army’s officer corps, he demanded a full court-martial to clear his name. A panel of 13 officers thereafter ruled that he had indeed acted with honor on the fateful night.

Howe and his army broke camp at dawn the morning after the fight. The British general, having ascertained that Washington’s defensive position was too strong to breach, instead headed for Philadelphia. Across the Schuylkill in the American bivouac, a Pennsylvania officer who had escaped the Paoli killing fields summed up the experience in a rather stunning understatement. Describing the engagement in a letter to his wife, he wrote, “Fortune has not been sublime to our Division.”

Perhaps deeming that euphemism insufficient, he felt compelled to add, “The carnage was very great.”