The Iliopsoas Muscle Group: Location and Actions

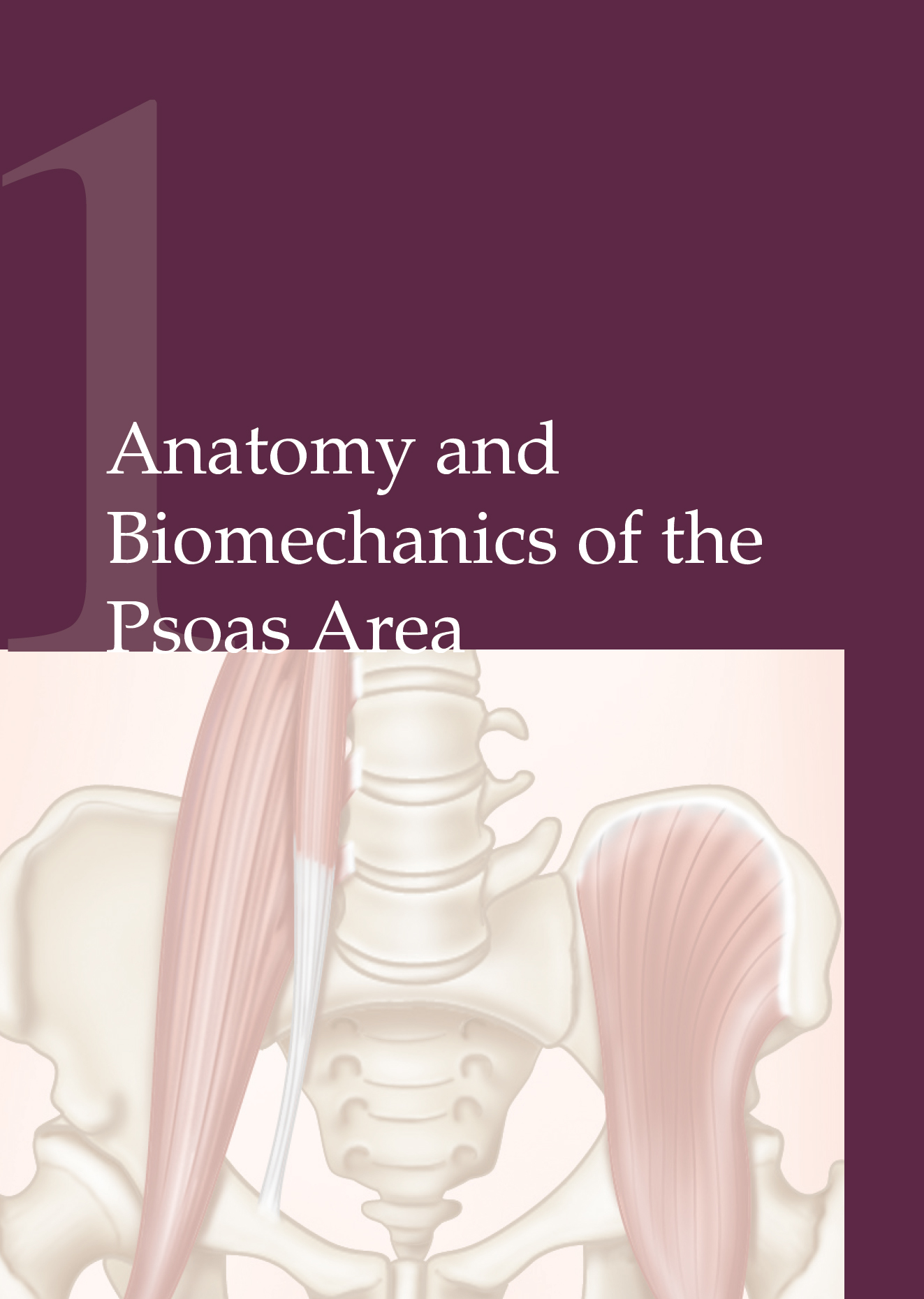

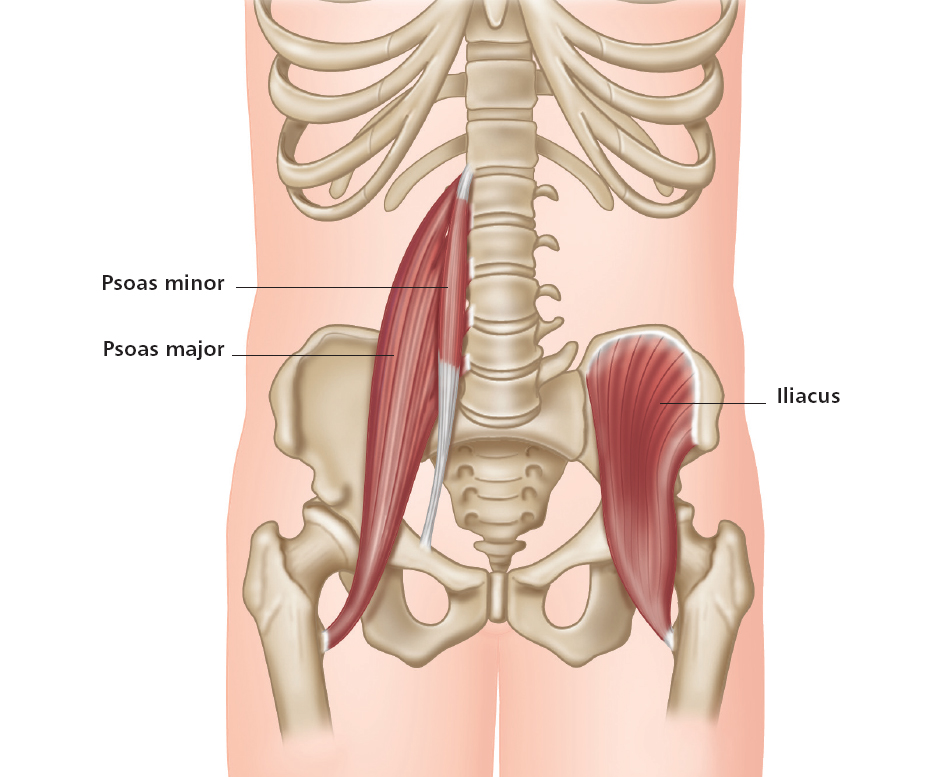

Deep within the anterior hip joint and lower spine lies the psoas major muscle. Sometimes called the “mighty psoas,” it is the most important skeletal muscle in the human body, as it is the only muscle that connects the upper extremity to the lower extremity (the spine to the legs). This makes it a very significant postural muscle and mover and stabilizer of two different joints: the iliofemoral joint and the lumbar spine. The muscle is also located near the body’s center of gravity, so its role becomes that of regulating balance, and affecting nerve and subtle energies as well.

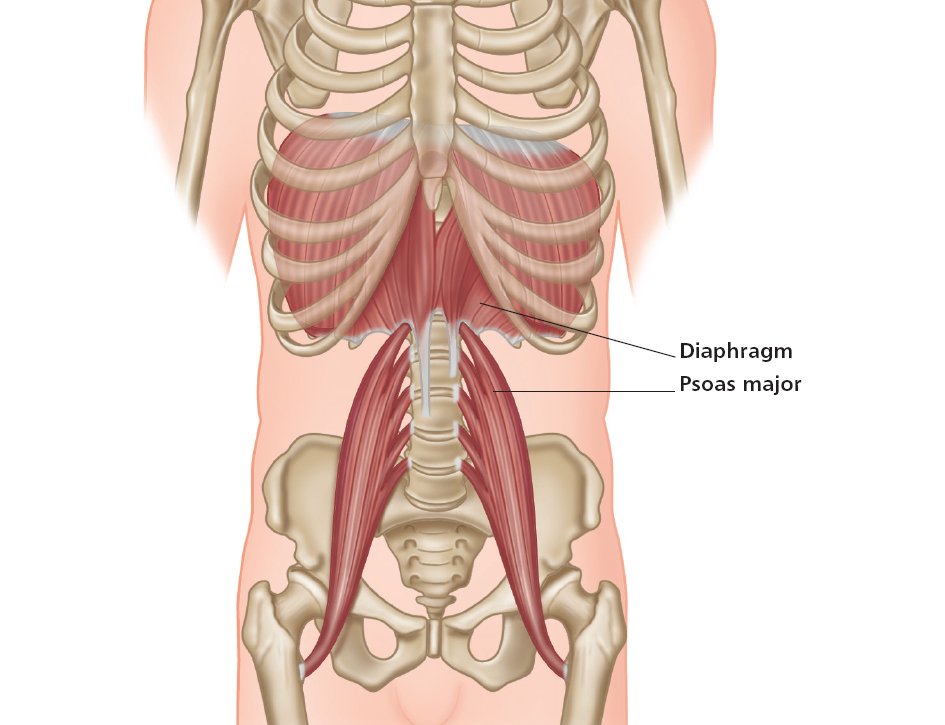

Figure 1.1: Psoas major.

The psoas has a major and a minor muscle, mostly synergistic at the lumbar spine. The difference is in their distal attachments: the major is the one that connects the femur to the spine (lower to upper extremities); the minor connects the pelvis to the spine. Some say the minor will become extinct, as it was important when humans walked on four legs, and not necessarily needed now. It is also a very weak mover. In fact, some people only have it on one side, or do not have it at all. When only the word “psoas” is used, it is generally understood to be the psoas major, or a combination of the major and minor as one muscle group.

Do not pronounce the “p” – phonetically it is “so-az.”

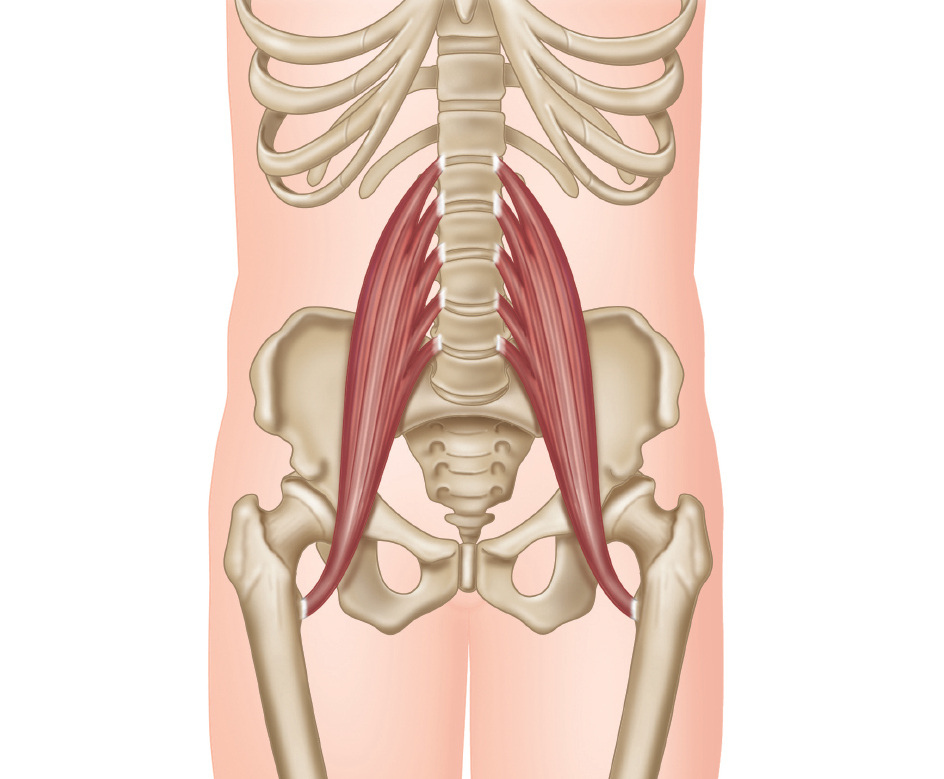

Both psoas muscles are part of a larger muscle group called the iliopsoas, which also includes the large iliacus. This group, contracting simultaneously, flexes the hip. It is the deepest of the hip flexors, and possibly the strongest as a muscle group. The iliacus attaches from the femur to the iliac bone of the pelvis, while the psoas major distally attaches to the femur, and proximally (nearest to the center of the body) attaches past the pelvis to the transverse processes of the first through fifth lumbar vertebra and sometimes the twelfth thoracic vertebra. Most sources have stated this allows at least part of the psoas to flex the lumbar spine, although it is being debated. If the femur is fixed, the iliacus will act at the pelvis, while the psoas may work on the lumbar spine. It can even use its lumbar fibers to extend the spine. This contradiction is explained in more detail later.

Figure 1.2: Iliacus.

The iliacus can also aid the pelvis in tilting forward, along with other hip flexors such as the rectus femoris. This forward tilt has a tendency to enhance lumbar lordosis (anterior curving of the spine), so the psoas must be strong yet pliant enough to help stabilize the area from too much advanced lordosis, or “sway back,” one of the most common conditions of poor posture. The abdominals can also help counteract this (specifically the rectus abdominis), as can the spinal extensors. The psoas becomes its own antagonist in stabilization between lumbar spine flexion and extension.

Centering the pelvis with muscles other than the psoas major and maintaining neutral (natural) spinal curves is key to allowing the psoas to do its many jobs without fatigue.

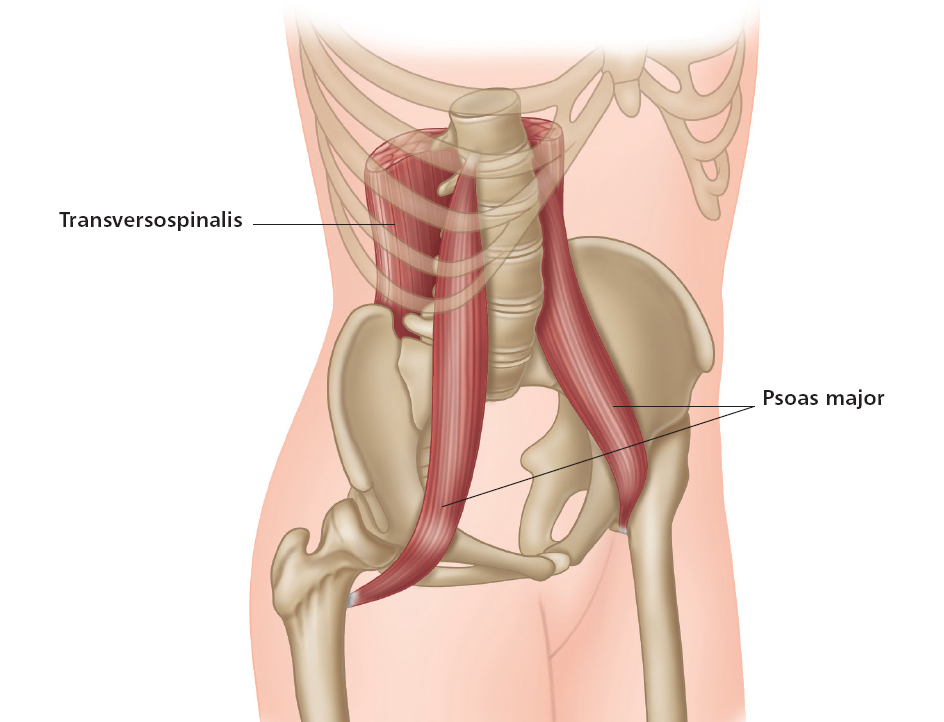

Research suggests that the psoas muscles, by forming a muscle bundle around the lumbar spine with the lower transversospinalis muscles (see figure 1.5), can help erect the lower spine, while other fibers can flex the area. Either way, as a core muscle the psoas is a force in correct body alignment. It is also of utmost importance in the transfer of weight through the trunk to the legs and feet while moving (and even when standing), as it helps to position the spine, pelvis, and femur in relation to one another.

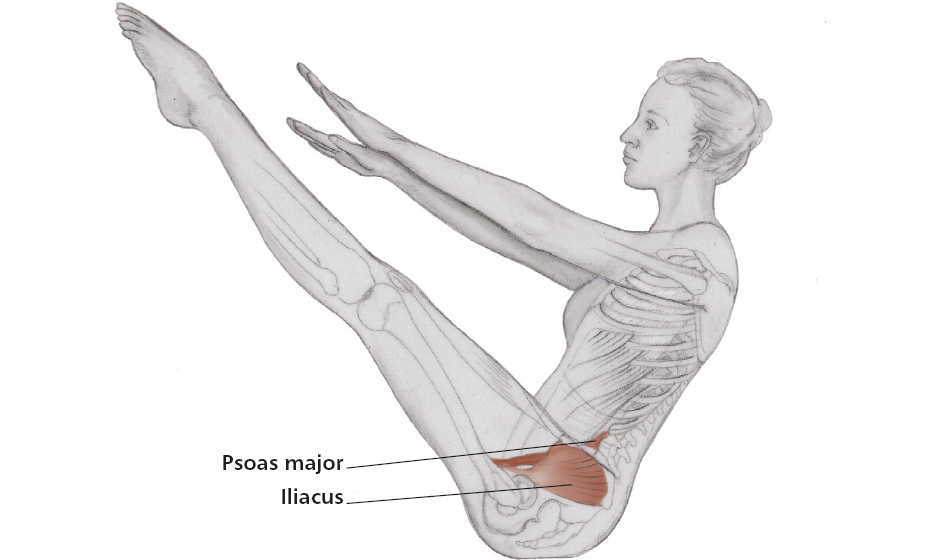

Figure 1.3: The iliopsoas muscle group. Imagine the muscle structure on both sides of the body to realize the full extent of the group.

The deep yet powerful three-muscle group of the iliopsoas working together can bring the thigh anteriorly (flexion of the hip), along with other anterior hip muscles. When the pelvis is stationary, one can isolate the psoas major by lifting the leg up in front of the body, as in the sitting “V-position.” With gravity as resistance, this engages the psoas in strong support of the lumbar spine, as well as some minor work at the hip.

Figure 1.4: V-position, isolating the psoas major.

As with most spine muscles, the psoas can also aid lateral bending of the lower spine (the right psoas will contract to bend the spine to the right, ipsilaterally) and contralateral rotation (the right psoas will contract to produce rotation to the left). These are very minor and weaker contractions of the psoas as compared to those in its other roles.

Proximity of the Psoas Major to Other Structures

The psoas works with many other major muscles to produce and stabilize movement; these will be discussed throughout the book. Here the supporting group of lower spinal extensors will be discussed.

The transversospinalis muscle group is part of the deeper posterior muscles, specifically the semispinalis, multifidus, and rotatores muscles. The last two form a bundle around the lower spine with the psoas major and help straighten the spine, which is in conflict with the psoas’s action of flexion of the lumbar spine. This is where practical knowledge comes into play and the Anatomy Trains work of Thomas Myers (2009). He explains the upper, anterior psoas fibers of the lumbar portion as appearing to help with flexion, while the lower, inner fibers help with extension. Other scientists describe the reverse. While the “jury is still out,” the most important thing to keep in mind is that the psoas in an erect spine acts as a stabilizer more than a mover, with stronger spinal extensor and flexor muscles doing much of the contractional work.

Figure 1.5: The deep posterior muscles in relation to the psoas major.

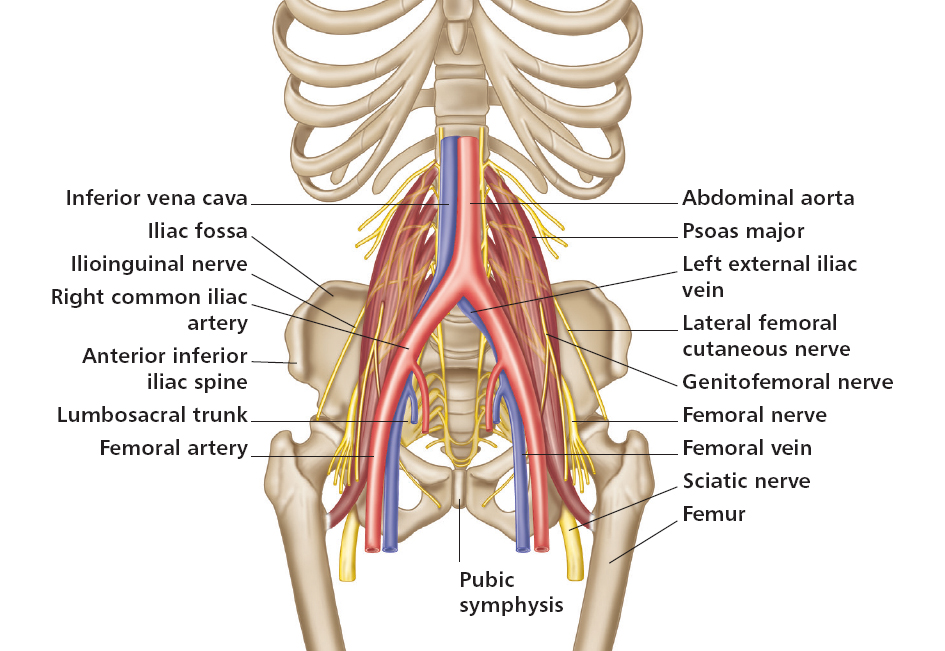

To palpate (touch) the psoas area, one would have to begin at the front of the body about 3 inches below and to the side of the naval, then travel past the abdominals, some organs, and other muscles (which is almost impossible). There in the deep core lies the psoas, one on each side of the lower spine. It is a difficult muscle to reach because of its proximity to organs, arteries, and nerves, so this is usually not advised. The muscle moves down the front of the pelvis and femur neck to attach on the lesser trochanter on the inside of the upper femur. It goes behind the inguinal ligaments that run from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) of the pelvis to the pubic tubercle, which are both prominent points that jut out to the front of the pelvis and can be easily found. One can feel the contraction of the hip flexors by finding the lower outside rim of the ASIS and pressing there, as the thigh is lifted forward in hip flexion.

The ilioinguinal nerve supplies sensation to the area and must be considered in the careful treatment of the muscle, as well as the proximity of the external iliac artery along the medial border of the muscle. The direct continuation of the external iliac is the femoral artery, which supplies blood to the greater part of the lower extremity. The genitofemoral nerve can also be affected by closeness of the psoas and taken into account in treatment.

As mentioned before, organs can be associated with the psoas because of its central location. The kidneys, ureter, and adrenals are very prominent in the mid-section and must be addressed with care during therapy for the psoas.

Fascia covers the psoas, as it does other muscles. Fascia is a connective tissue that surrounds and separates muscle. Lumbar fascia (called lumbar aponeurosis) blends with psoas fascia, which extends from the first lumbar vertebra toward the sacrum, and from the crest of the ilium to the quadratus lumborum and iliacus muscles. The iliac fascia then connects and accepts the tendon of the psoas minor (if present) as well as the inguinal ligament. On toward the thigh, the psoas and iliacus fasciae form a single structure called the iliopectineal fascia. This fascia passes behind the femoral vessels, but the lumbar plexus nerve branches are posterior to it, making it an extremely complex area.

There is a large bursa (fluid-filled sac that provides cushioning) within the hip joint cavity. This bursa usually separates the psoas major tendon from the joint capsule and the pubis.

The positioning of the psoas in relation to the leg, pelvis, and trunk is most important. It acts as a structural conduit, guiding the support of the spine as its muscle fibers travel down and outward. However, these muscle fibers then travel back in toward the thigh, making the psoas major a fusiform muscle. This is a spindle-shaped muscle, wider at the middle and thinner at both ends, not unlike the biceps brachii. It appears to have an elongated trapezium shape, but must be observed three-dimensionally as it slightly spirals along with the pelvic structure it enhances.

The suspension of the psoas from the trunk to the legs helps channel movement from the spine, and aids the transfer of weight from the torso to the thighs in locomotor movements such as walking. If the psoas on one side is unbalanced with the other side, imagine what this might do to the gait or stride of a walk. If both psoas muscles (right and left sides) are healthy and can move freely, there is a steady flow to the movement and the energies that happen within the body systems.

Figure 1.6: The psoas in balance while walking.

The Psoas as a Major Mechanism

The psoas is considered a core muscle that acts as a keystone, central and superior to the “flying buttresses” of the femurs and thigh muscles. This major architectural concept is also apparent in the skeletal pelvis/leg relationship, and supports the human body much like an arch does in building structures.

The psoas travels vertically from the spine to the leg, and diagonally across the pelvis. As a skeletal muscle that passes across more than one joint, it becomes bi-articulate (a muscle that works two joints). This is a most important concept, but it is interesting to note another role of the psoas: a shelf, supporting internal organs, along with the pelvis as a basin, and the pelvic floor.

Thus, any force of the psoas (muscular contraction) can stimulate and massage organs such as the intestines, kidneys, liver, spleen, pancreas, bladder, and/or stomach. Even reproductive organs are affected. Some deep, central, internal organs are referred to as viscera, so communication from organs to the brain can be called visceral messaging. The psoas, because of its proximity to major organs, can play a role as a reactor to these stimuli, thus affecting what is commonly termed “gut feelings.”

Figure 1.7: The proximity of nerves (lumbar nerve complex) and arteries to the psoas.

It can also affect nerve innervation, especially the lumbar nerve complex that passes through it. The aorta (the largest artery) lies in a similar path to the psoas, so body circulation and rhythms can become intertwined with the psoas as well.

Another remarkable fact is that the psoas and the diaphragm, a major breathing muscle, come together at a junction point known as the solar plexus. This is not an actual anatomical object like an organ, a bone, or a muscle; it is more an area behind the stomach, centered near the naval and in front of the aorta and diaphragm, which houses a nerve network. It is associated with the ancient chakra system and discussed in more depth in the spiritual section (Part III) of this book.

Figure 1.8: The psoas and the diaphragm come together at a junction point known as the solar plexus.

No wonder the psoas is so special. It has been called the “hidden prankster,” the “opinionated psoas,” the “great pretender,” a “conductor,” and the “fight or flight muscle,” among other things. My wonderful physical therapist, Dr. Gary, calls it the “front butt.” What a marvelous identity!

The psoas can:

It can also adapt to differences in many ways, as long as it is in a state of release (not tight or “frozen”) and it is healthy. The following chapters will demonstrate how to keep the muscle in balance through various types of exercise, and discuss its role in the emotional and spiritual state of the human being.

The psoas affects the whole person.