The lower (lumbar) spine is an elaborate system of nerves, bones, muscles, ligaments, and other tissues that combine to create one of the most abused areas of the body. In the United States alone, lower back pain has become a “disease” of unknown proportions, causing an infinite number of insurance claims, unemployment, and disability, resulting in a loss of billions of dollars each year. It can be either acute (short term) or chronically progressive, with symptoms ranging from soreness to an inability to stand up and move.

Anatomy of the Lumbar Area

The lumbar spine has the same functions as the rest of the spine: support, mobility, connection, balance, and protection. The differences lie in its location and size. The lumbar area supports the weight of the upper extremity. The vertebrae are larger and thicker to help accomplish this, but this can also limit movement. It is also an integral part of the core.

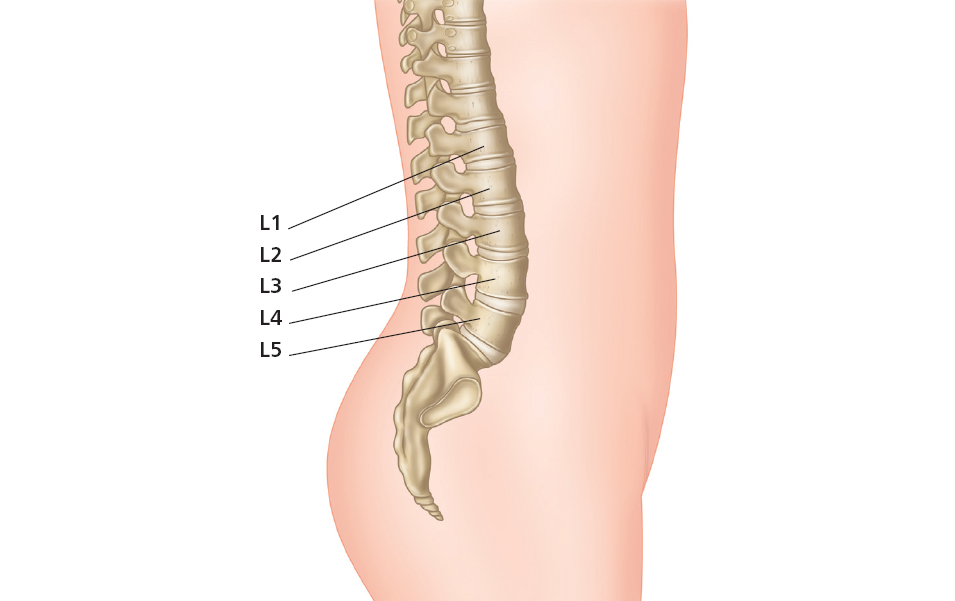

There are five lumbar vertebrae, approximately located in the center of the body. Because they are larger and thicker than the other bones of the spine, they are also heavier. They have a lordotic curve, meaning anterior curve or toward the front, which counterbalances the thoracic posterior curve. The discs (the cartilage in between the bones) are one-third the thickness of the vertebral bodies, which allows for mobility in flexion, extension, and lateral bending; but rotation is limited due to the straight projection, short length, and bulky properties of the posterior spinal processes, along with the orientation of the facets (articulating surfaces of a vertebra process).

Figure 3.1: The lumbar spine.

As seen in previous illustrations, the psoas is also centrally located here, with attachments to the lateral lumbar processes. Therefore, the psoas becomes one of the main muscles that can affect the condition of the lower back as well as the positioning of the pelvis. Both the lower spine and the pelvis are interdependent: they must be in balance and alignment with each other to function properly. Any incongruence will affect other areas, from the upper spine to the feet, and even cause tension in the jaw. Essentially the entire length of the body is affected, but especially the lower back.

The causes of lower back pain can be difficult to determine in each individual. The following is a list of the more common sources of pain:

Although all ages and nationalities and both genders can be affected, the primary group targeted is aged between 30 and 60. Much research has been done to explain the reasons for such widespread lumbar distress, with results showing that increasingly sedentary lifestyles, coupled with intermittent vigorous exercise, is a strong culprit.

Psoas and Pelvic Floor Exercises to Aid the Lower Back

This is a 10-minute Level I routine (depending on injury) for the lower back. All exercises are performed in a supine position on the floor and can be done daily.

Warm-up: Lie on the back, with the knees bent and feet on the floor. Breathing deeply, engage the transversus abdominis on a strong exhale (by “cinching the waist”), to stabilize the lower spine/pelvis.

Cool-down: Constructive Rest Position (pages 20–22).

Causes of Back Pain: Scenarios

Scenario 1: The Weekend Athlete

Most people in this category will have trouble admitting it. No one wants to confess that they are no longer serious athletes who used to spend almost every day of the week training.

Whether a student or a professional, there are millions of people who are spending more time sitting and less time moving. Time is a consideration, as the stress of everyday living such as working, raising a family, commuting, and studying (to name a few), takes away precious moments that could also include taking care of one’s health.

Time management is important, and the lack of it has spawned a new industry of courses, videos, and the like to help advise and teach usually intelligent people how to handle their daily lives. We are all guilty, as we allow many things to get in the way of our own health. Consideration for the physical condition of the body cannot be overlooked for long, as injuries such as lower back pain will result.

Scenario 2: Children

By now most people are aware of a growing trend of more obese children. In the United States, a country where so much is made available to a majority of the population, incorrect eating habits and sitting too much have affected our children’s health.

As first lady, in 2009, Michele Obama chose this one problem for the main focus of her time in the White House through the “Let’s Move” program. Uniting parents, children, teachers, leaders, and medical professionals, it is hoped that through community effort and national attention this epidemic will be curbed. Physical activity needs to be included in the process, as being overweight can and will affect the lower back, among other things.

Scenario 3: The Overachiever

This is the opposite of the above two situations as far as movement is concerned. For purposes of this book, the overachiever is the physical “nut” – the one who overtrains. The body’s example of “type A,” this person does not know when to stop. He/she might exercise every day, for hours. The body fatigues but this person keeps going, which affects the very physiology of the joints and muscles. They can be overloaded to the extreme, without taking in enough nutrients needed to keep them working properly.

Hence the following story.

Psoas Story: The Case of the Elusive Six-Pack ABS

Dr. Gary Mascilak, D.C., P.T., C.S.C.S.*

Dr. W is a 28-year-old male who was presented to my office with lower back pain. Studies show that more than 8.5 out of 10 people, at some point in their lives, will have an episode of back pain that causes them to alter their daily functions.

The challenge for clinicians is always to determine the cause of their patient’s symptoms. It is quite like detective work: I look for clues in the way they walk into my office, how they sit when I am talking with them, how they move their torso in various directions, and especially how they squat. Mobility of the hips, flexibility of the lower extremity musculature, and core strength are just a few areas that are critical to assess.

The most important component of a clinician’s examination is taking a thorough history. Dr. W seemed somewhat agitated during this process, and I did not think his reaction was merely from pain. When I politely inquired if he was very uncomfortable, he said he was more frustrated because he had not been able to do his “normal” things for over two weeks. He looked very fit, so I asked him if exercising was one of the things he could not do as of late, since individuals who routinely work out and then have to stop for one reason or another are chemically deprived of their natural opiate and endorphin “feel good” chemicals, and can get somewhat “cranky.”

Also having sensed that Dr. W may be a Type A person, I thought it was imperative that I understand what his workout entailed, as incorrect performance of exercise or excessive volume of a particular exercise can often be the culprit for the development of muscle imbalances and subsequent symptomatology. When Dr. W reported doing 1,000 sit-ups a day (2 sets of 500), I knew we had discovered a key component to his pain. Examination ultimately revealed lumbar facet syndrome, a condition where the joints of the lower back become compressed and irritated. The normal concave arch (lordosis) in his lower back was accentuated and excessive. Evaluation revealed marked hip flexor tightness on both sides, and exquisite tenderness to palpation of the psoas muscle bilaterally. Additionally, the exam revealed significant lower abdominal and gluteus maximus weakness, which should not be the case with someone working out for almost two hours a day, five times a week. He provided me with the exercises he was doing, and when asked to describe one of the 1,000 sit-ups he was performing each day, he indicated a basic crunch move.

Dr. W’s exercises were far from a balanced routine and definitely not specific to address his existing muscle imbalances, which actually caused his repetitive injury. His crunch exercise, as is so commonly performed, was utilizing primarily his hip flexors to perform the movement, compensating for weak abdominals. Although crunches can be performed with proper instruction, good form, and knowledge about how to properly set the core musculature (including the pelvic floor and lower abdominals – transversus abdominis), I prefer to train the abdominal wall with different types of exercise that allow proper recruitment of the aforementioned stabilizing muscles, and prevent hip flexor and psoas hyperactivity and compensation.

The reverse crunch is preferred to the standard crunch as it makes the person bring the knees maximally to the chest, thereby placing the psoas in a position where it is helping flex the hip, and does not aid the abdominal muscles much to perform actions at the spine (the movement of drawing the knees to the chest and lifting the lower spine off the floor). Proper instruction is obviously still required and form needs to be monitored until mastered.

Release of hip flexors was done with soft tissue work on Dr. W, and he was instructed in proper psoas stretching exercises in all three planes of motion. Additionally, he was given exercises and instruction in strengthening his gluteal, lower abdominal, and other core muscles.

In three to four weeks, these exercises reduced the excessive arch in Dr. W’s back and relieved his back pain. As a physician who attempted to treat himself for over a month with no real improvement, Dr. W inquired how I came to the conclusion as to the cause of his symptoms so rapidly. I told him that after logically examining all the clues for his case, especially his history, ultimately deducing the improper performance of the sit-ups was quite elementary (and no . . . Dr. W’s last name was not Watson).

There are more scenarios, to be sure, but the above three are widespread. Exercises and/or positions to alleviate lower back pain can be found throughout this book. The appendix, “The Hip Flexion Society,” will also be an invaluable aid.

The following chapter will address the more specific conditioning program of Pilates and how it works the psoas and lower back (to excess if done incorrectly).

The most important thing to remember in any exercise program is:

Muscle balance is key to a healthy body.

Review: Fact or Fiction?

Lower back pain is a disease.

Fact – it is a specific disorder that can become a medical condition affecting many people, and is therefore a disease.

The lumbar spine is the lower back.

Fact – there are five lumbar vertebrae that, as a single area, curve anteriorly and make up the main length of what is called the lower back.

The lumbar spine is considered small.

Fiction – although it comprises only five vertebrae, the vertebral bodies are the largest and heaviest in comparison to the rest of the spinal column.

The lumbar spine can move in all three planes.

Fact – this is true of all mobile sections of the spine, yet each area has its limitations. At the lumbar spine, rotation is minimal because of the characteristics of its bony processes and facets.

Rotation as a joint action of the lumbar area should be forced.

Fiction – since the action of rotation is minimal in the lower back because of bone configuration, any forceful movement beyond normal can be detrimental. (Yoga teachers and students: beware of spinal twisting in this area!)

Lordosis is a disease.

Fiction – lordosis is the term used to indicate a concave, or anterior curve, in the spinal column, which is the correct curvature for the lumbar and cervical areas. If the lordotic curve is advanced, it can create problems, but the term itself indicates the normal position.

The psoas major and the lumbar spine are connected.

Fact – tendons of the proximal psoas are attached to all five lumbar vertebrae.

The psoas is considered an abdominal muscle.

Fiction – along with the quadratus lumborum, it makes up the posterior abdominal wall, but is not one of the four primary abdominals.

The psoas is one of the main muscles affecting the lower back.

Fact – since it is located and attached here, its condition warrants attention in lower back pain.

Sitting can cause lower back problems.

Fact! – See the appendix on “the hip flexion society.”

*Breath work is important – a private session with a qualified instructor will aid in this, and also provide cueing to correct any misalignment or misuse.

*Dr. Gary Mascilak is the clinic director and co-owner of Integrated Health Professionals, a multi-disciplinary rehabilitation center in Sparta, New Jersey. He is a licensed doctor of chiropractic, physical therapist, certified strength and conditioning specialist, and board eligible diplomate in orthopedics. He has been in practice for over 23 years, treating a variety of orthopedic and sports injuries, from professional to adolescent athletes and everything in between. He has lectured nationally on rehabilitation techniques and has contributed articles to professional journals and magazines, including Runner’s World and Sports Illustrated.