XIV

The interview with Grover was not very satisfactory. In the first place, he insisted that they come up into the loft. “It is my office,” he said, “the White House from which I shall govern the F.A.R. If you want to see me, you must come up here. You can hardly expect the president to come to you.” And when they pointed out that Mrs. Wiggins could not get up the stairs, he merely remarked that that was too bad.

So Jinx, Robert, Charles, and Henrietta went up.

Grover was still in the control room of Bertram, who received them sitting in Uncle Ben’s armchair, with his back to the long bench on which sat Simon and a number of the more important birds who had voted for him. Under the bench, tied tightly, was Freddy. And John Quincy and X sat on Bertram’s shoulders.

“Before you begin,” said Grover, who had tuned down Bertram’s microphone so that his voice was not much louder than it usually was, “I had better tell you what I intend to do. I know what you are going to say, but you don’t know what I am going to say. So listen.

“I am the first president of the F.A.R., and I propose to govern the country. You are the heads of the party which opposed my election, and which still opposes it. I do not intend to be hampered in carrying out my plans for the F.A.R. by that opposition, and so I have seized one of you and intend to hold him as hostage for your good behavior. As president, I may point out, I have a perfect right to keep him in prison. As long as you behave yourselves and do as you are told, as long as you obey the laws which I shall pass, Freddy will be kept comfortable and happy. But if you plot against me, if you oppose my commands, he will suffer for it. Do I make myself clear?”

“You do, bug-eater, you do,” said Jinx flippantly. “But when you say you’re president, you’re talking through your hat. Or through Bertram’s hat. Bertram’s president, not you.”

“Have it your own way,” said Grover indifferently. “Bertram will punish you if you misbehave. And if you run away, he will punish Freddy.”

Jinx scowled for a moment at Bertram, who just sat there motionless, with his left arm resting on one arm of the chair and his right arm—the one that acted up when you tried to work it—hanging down straight over the other. It made Jinx feel queer. Ronald had always run Bertram, and Jinx and the other animals had got to think of the clockwork boy as a real person, and one whom they were fond of. But now he was different. He looked dangerous, and frightening. The woodpeckers, sitting motionless on his shoulders, made him seem strange, too. And the row of birds on the bench, among whom were several hawks and two long-legged, sword-billed herons, made him uncomfortable with their cold stares. Even his old enemy, Simon, whom he had never been afraid of, made him feel nervous.

He looked at his companions. “Nothing we can do now, I guess,” he said.

“No,” said Robert thoughtfully, “I guess not.”

But Henrietta said: “Maybe there’s nothing we can do, but there’s something I can say. Grover, you’re making a fool of yourself. After all, you’re nothing but a bird, and like all birds you’re vain and silly and headstrong. Oh, I know! I’m a bird myself. You’ve heard the story about the woodpecker that got hold of the lion’s tail and thought it was a worm? Well, that’s you. But, as Jinx says, there’s nothing we can do now. As a matter of fact, if we do nothing, that’s enough. By and by the lion will turn around and bite off your head. Snap! And we’ll all go on as we did before you came.”

“Thank you, Henrietta,” said Grover. “I will remember what you say. But there’s one thing more before you go. I want you to know that you will have nothing to lose by behaving yourselves. The laws that will be made will be for your own good. You will be citizens of a greater country than you would ever have been under a president who was nothing but a yokel, like Mrs. Wiggins.”

A loud snort from the foot of the stairs made Jinx grin, in spite of his anxiety to get away. Evidently Mrs. Wiggins was listening downstairs.

As they turned to go, Simon said: “Mr. President, hadn’t you better tell them yourself about the new orders? They may not believe me.”

“Very well,” said Grover. And then in a solemn voice he declaimed: “Order number one, issued by me, Grover, first president of the F.A.R. Whereas, certain of our citizens have sought redress from me for oppression and maltreatment suffered at the hands of certain other citizens;

order number one, issued by me

“And whereas, their complaint setteth forth that they have been pursued, chased, ignominiously beaten, and deprived of their proper habitations and means of livelihood, and have been housed in miserable dens unfit for citizens of so great a republic;

“And whereas, the conditions as set forth in their complaint have upon investigation been found to be as stated;

“It is hereby ordered that these citizens, namely one Simon, a rat, and his wife, children, and dependents, to the number of twenty-one or more, be hereafter permitted freely to take up residence in any barn or building they may choose, to occupy said premises freely and without molestation under pain of fine and imprisonment;

“And it is further ordered that they be permitted freely, and without let or hindrance, to take for their own use such grain or other food as may be found in said buildings, to an amount not exceeding one peck per rat per day.”

Grover stopped and the animals looked at one another again, and Henrietta said: “Now say it all over in English.”

“I know what he means,” said Robert. “The rats can live in the barn and eat all the grain they want to.”

“Come on,” said Jinx suddenly. “Let’s get out of here before I start chewing my own tail.” And he started for the stairs, followed by the others.

In the barn downstairs their friends were waiting for them.

“We heard it all,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “Robert, what’s a yokel?”

“Search me,” said Robert. “But I don’t think he meant it as a compliment.”

“No,” said the cow. “But he’s afraid of me or he wouldn’t call me names. That’s what people always do when they’re scared. Well, I’m scared, too, so that makes us even. I’m going home. I want to think. There’s nothing we can do now. Grover’s got the upper hand, and the thing to do for a while is to go on about our regular business as he told us to. At least we’ll pretend to. If anybody thinks of a plan, talk it over with one or two others. We can’t hold any big meetings, but we don’t need ’em.”

“You’re our president,” said Hank, “and we’ll do as you say.” And the others all agreed.

That afternoon Grover made a tour of inspection of the farm. With John Quincy and X on his shoulders, Bertram strode rapidly in and out of buildings, and across fields, and through the woods, accompanied by the birds of his staff. The two herons, Eliphalet and Lemuel, whom he had appointed his bodyguard, kept beside him and menaced with their long bills any animals who approached too close. Everywhere he issued orders. Many of the animals who had opposed his election were given extra work, and some were even moved from their homes. Hank had to move out of the barn which had always been his home into the cowbarn, as Grover said the barn was to be used for government offices. Eek and Quik and Eeny and Cousin Augustus also had to leave the barn and move into a hollow tree. Mrs. Wogus and Mrs. Wurzburger were allowed to go about the farm as they always had, but Mrs. Wiggins, whom Grover considered one of his chief enemies, was forbidden to leave the cow-barn on pain of arrest. The chickens had to leave their comfortable chicken-house at ten minutes’ notice and move down into the woods. The chicken-house, Grover said, was to be used as barracks for soldiers.

“Soldiers!” said Henrietta. “What are you going to do—start a war?”

“You’ll find out,” said Grover. “Come. Pack up. You have ten minutes.”

And the chickens packed. All the other animals, too, did as they were ordered. It was all they could do, for none of them was strong enough to fight Bertram.

But with old Whibley, Grover struck his first snag. On the tour of inspection, Bertram stopped under the old beech tree and shouted: “Owls! Come out!”

After a minute old Whibley appeared at the entrance of his hole. “Bug-eater again,” he said. “Know that voice of yours anywhere. Stepped up with a microphone so it’ll sound important. Like wearing high heels to make yourself look taller. Same voice. Little foolisher, if anything.”

“Be careful what you say, owl,” boomed Bertram. “I come to offer you peace.”

“Peace?” said old Whibley. “I can get peace by walking back into my house. Go away, woodpecker.”

“Listen,” said Bertram. “I am president of the F.A.R. The F.A.R.! A little hill farm, no bigger than half a dozen city blocks! Do you think I am satisfied to be president of a country like that? No! Tomorrow morning my armies will move against Zenas Witherspoon’s farm, over the hill. If the Witherspoon animals agree to join the F.A.R., well and good. If they prefer to fight, it will, I assure you, be a very short war. We shall take them in. Then we shall march on the Macy farm, across the valley. And so on. Within three months every animal in New York State will be a citizen of the F.A.R. Within a year, or two at the most, I see a great republic of animals, stretching from coast to coast, a far-flung empire—”

“Far-flung dishwater!” snapped old Whibley. “Never heard such nonsense!”

“Wait,” said Bertram. “I have come to offer you a high honor, a position in the government under me. We need brains—”

“I’ll say you do,” put in the owl.

“We need brains like yours,” went on Bertram. “You could rise high, do great things—”

“Stop it!” interrupted the owl. “I can rise high enough without your help. You mean well, Grover. There’s just one thing wrong. Mrs. Wiggins is president of the F.A.R.—not you. Go back to your bugs—leave the country to her. She knows more about it than you ever will.” And he went back into his hole.

Bertram stood still for a moment. Then he raised his left arm and pointed. “Go bring him out.”

Three big hawks swooped from the branches on which they had been sitting, circled, and flew toward the tree, and the two herons, with much flapping of wings, managed to get to branches from which they could reach into the hole with their foot-long beaks. But the owl didn’t wait for them. Followed by his niece, Vera, he burst out of the hole, dodged around a tree trunk away from the hawks, and, coming up behind Lemuel, gave him a blow with his powerful wing that knocked the heron squawking from the branch. At the same time Vera swooped expertly through a tangle of branches and dropped on the other heron, who, before he could even get his bill into position to strike, got a crack on the head from her strong curved beak that made him shut his eyes and cling to his perch desperately. And then the owls turned on the hawks.

Neither hawks nor herons can maneuver well in thick woods. The light is dim, and they are not accustomed to diving and swooping among thick foliage. The herons, indeed, had already given up, for their gangling legs and long beaks caught on twigs and got wedged between branches until they hardly dared move. The hawks kept it up for a time, pursuing an enemy whom they seldom even caught a glimpse of, yet who seemed able, somehow, to be far in front of them one moment, and the next to be snatching a beakful of feathers from their wings or tail, or pouncing and ripping painfully with sharp talons.

And all the time old Whibley laughed his hooting laughter.

Grover, peering out of the little window in Bertram’s chest, ground his bill in anger. The hawks were brave, he knew. They would fight until they dropped. But he knew too that he couldn’t afford to have three of his best fighters in the hospital if there was to be a battle tomorrow. So at last he called them off.

They came down and perched beside him, ruffled, panting, and bedraggled. And Vera and old Whibley perched above them, with hardly a feather out of place.

“Haven’t had so much fun in years,” said old Whibley. “Must thank you, bug-eater, for providing such good entertainment.”

“You wait!” was all Grover could say. “You wait!”

“Not going to,” said the owl. “It’s war, Grover, and I’m going to start right in today. Duels are silly, but war—that’s something different. Besides, Freddy and Mrs. Wiggins are friends of mine. Look out for yourself, Grover. Especially at night.” And he and Vera both laughed their eerie, hooting laughter. Grover shivered and, turning Bertram, marched him out of the woods.

In the meantime Freddy was not enjoying himself much. He had been untied and taken downstairs and shut in the box stall with three guards: Ezra, Simon’s eldest son, and two other rats. The box stall had once been used by the animals as a jail, and escape from it would have been pretty difficult, even if it were left unguarded. But with the rats there, escape was out of the question. They knew what was to be expected from Freddy’s friends, and not a mouse could get near the stall.

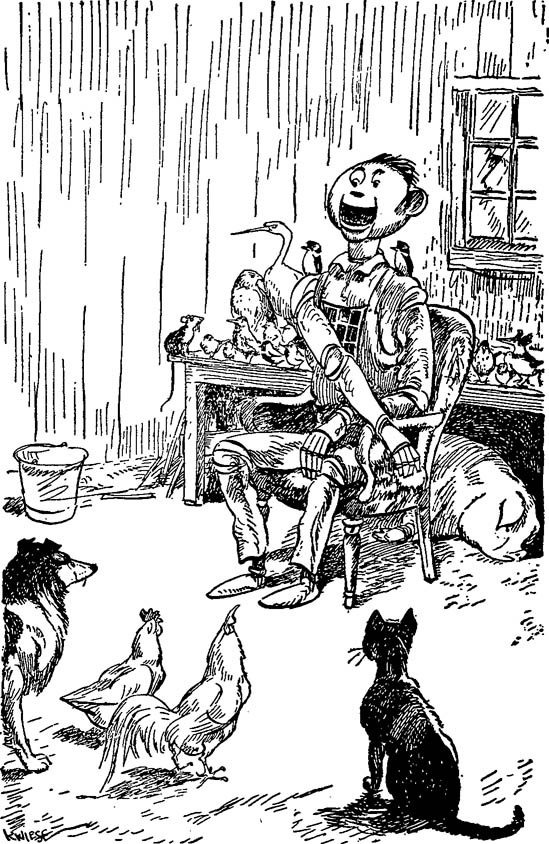

But the rats had a good time at first. They made up ribald songs about Freddy and sang them. One or two of them were quite funny and even made Freddy laugh. And when they looked at him in surprise, he remembered his belief in the power of laughter and burst into a roar.

“The song isn’t as funny as all that,” said Ezra doubtfully.

“I’m not laughing at the song,” said Freddy. “Just something I thought of.”

They pressed him to tell them what it was, but Freddy wouldn’t; he just kept on laughing, and by and by the rats got uneasy. They stopped singing and prowled around the stall, peering and listening.

“Aw, it isn’t anything,” they said at last. “He’s just trying to get our goat.”

“Sure, boys. That’s it,” said Freddy seriously. He was sober for a while, and then he began to chuckle as if he just couldn’t hold it in.

Before he was through he had the rats so nervous and unstrung that they sent word out, and three other rats took their places. By that time it was six o’clock, and Freddy was hungry. But the rats said orders were that he couldn’t have any supper. “Your friend old Whibley has been misbehaving,” they said. “So of course you get punished for it.”

After that, Freddy didn’t feel up to laughing any more, so he curled up and tried to go to sleep.

For a time the tramp of Bertram’s heavy footsteps and the sounds of bird and animal voices upstairs, to say nothing of the hunger gnawing in the pit of his stomach, kept him awake. By and by he fell into a doze, and watched a procession of dinners and lunches and breakfasts and bowls of soup and big platters piled high with food passing by, just out of reach. He moaned and tossed about in his sleep, and his guards woke up and grinned at each other.

“Beefsteak, Freddy,” whispered one.

“Apple pie,” whispered another.

Freddy moaned louder.

“Aw, let him alone,” said the third.

It must have been about midnight when Freddy was awakened by a sharp little whisper in his ear. “It’s me, Freddy—Webb. Quiet, don’t move.”

Freddy lay still.

“Listen,” said the spider. “We’re going to try to rescue you tomorrow while Grover and his army are attacking the Witherspoon farm.”

“But you can’t!” Freddy exclaimed. “It’s too dangerous.”

He had forgotten the guards, and now they jumped up and came over to him.

But Freddy remembered in time. He gave a sort of half snore that ended in a moan, and said, as if talking in his sleep: “Take it away, I tell you. Take it away!”

“Hey, Freddy, what’s the matter?” said one of the rats, putting a paw on his shoulder.

“Eh? Wh-what? What’s wrong?” exclaimed the pig, starting up and looking around wildly. Then he sank back. “What did you want to wake me for!” he said crossly. “I was just finishing a big plate of lobster salad and they were bringing me in a mince pie.”

“Guess it’s just as well I did, then,” said the guard with a laugh. “All right, boys. He was just dreaming.”

When everything had quieted down, Mr. Webb said: “I can’t tell you the whole plan now, for there’s lots to do and I must get back. But you be ready. When you’re out, we can decide what to do about Grover. And, by the way, don’t worry about the bank. Grover stopped there on his tour of inspection today and said that he supposed it was up to him to take charge of it, since the bank president was in jail. So he put X in charge of it. But John went down there just after they grabbed you this noon, and he dug another room and moved all the money and valuables into it, and then he closed it up so nobody would know where it was. Grover is planning to use that money, I think, but he’ll never find it now. Well, so long.” And Mr. Webb dropped down to the floor and tiptoed across it and up the wall and through a crack over the window to safety.

Freddy felt a lot better in his mind, but a lot worse in his stomach, for he was getting hungrier and hungrier. He couldn’t sleep, and there was no use trying to figure out how his friends planned to rescue him, so he decided to annoy the rats. And he suddenly gave a loud laugh.

The rats jumped up, squeaking excitedly, and rushed over to him. “What is it? What goes on? What’s the matter?”

Freddy blinked at them. “Oh, sorry, boys. Guess I must have had a nightmare.”

“A laughing nightmare!” said one incredulously.

“Sure,” said Freddy. “I often have ’em. Specially when I have something on my mind. Something funny, I mean.”

“Perhaps if you told us what it was, you wouldn’t have any more of them,” said the second guard.

“Perhaps,” said Freddy. “Good night, boys.” And he turned over.

Freddy had six more laughing nightmares during the night, each louder and more startling than the last. The three rats were wrecks by morning.