‘Whoever, then, possessed the power of regulating the quantity of money can always govern its value.’

David Ricardo, House of Commons, 1821

‘Nearly every theme in the [contemporary] monetary debate is a replay . . . of the controversies between the Currency and Banking Schools over a century ago.’

Tim Congdon, 19801

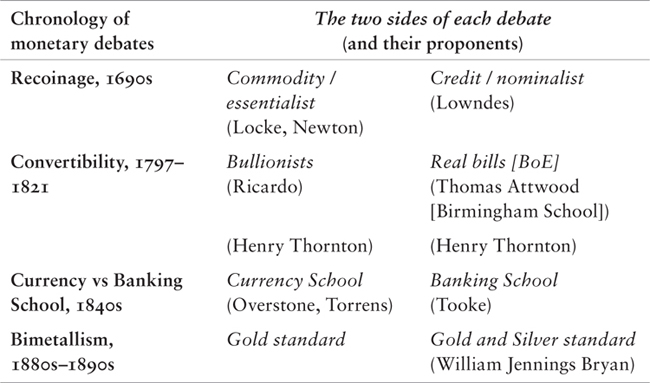

Figure 2. Four key monetary debates

In the 1690s, Britain, then on a silver standard, was at war with France. Full-weight silver coins were being exported to pay for foreign military expenses; ‘clipped’ or lighter-weight coins with the same face value but less silver were informally substituted in domestic circulation. By 1695, it was estimated that the vast majority of domestically circulating coins contained only 50 per cent of their official silver content.2 Prices rose by 30 per cent over the 1690s as the purchasing power of coins declined. The monetary authority (then the Treasury) had lost control of the money supply.

What was to be done to stop the country running out of money? William Lowndes, the Secretary to the Treasury, proposed devaluation. The Treasury would mint new coins of the same face value as the older coins but containing 20 per cent less silver, equivalent to a devaluation of 20 per cent, and declare them to be legal tender. Unless a limit was placed on counterfeiting, the result might be hyperinflation.

However, the philosopher John Locke, who was also asked to advise on the currency, rejected devaluation in favour of revaluation. Locke distinguished between intrinsic value and market value. It was because of its intrinsic value that metallic money could serve as a standard of value for all marketable things. A ‘pound’ sterling was simply a definite weight of silver. Its price, once settled, ‘should be inviolably and immutably kept [the same] to perpetuity’.3 Lowndes’s proposal was as deceitful as claiming ‘to lengthen a foot by dividing it into fifteen parts . . . and calling them inches’.4 The answer to Locke is that a quantity of silver is not an objective measure of value, but just a less fluctuating one than cows. His argument for fixing the currency in terms of a weight of silver was political: a fixed metallic standard was a token of the government’s integrity, not a property of the metal itself.

Locke’s proposal to revalue the currency reflected his political aims. In his social contract theory, the state was given a duty to maintain its citizens’ property. Silver coin was property, therefore its devaluation was akin to robbery. Behind Locke’s proposal to keep the value of money constant was the ideology of the creditor. The creditor should be repaid in coin of the same value as the coin lent. Any other course would defraud him. Such a ‘hard’ money regime would prevent the state ‘stealing’ the property of its citizens by devaluing the currency in which it settled its debts.

Locke had a practical argument for keeping the value of money (or price level) constant. He said that the previous standard had served England well for nearly a hundred years. The harm came from changes in the standard, which ‘unreasonably and unjustly gives away and transfers men’s properties, disorders trade, puzzles accounts, and needs a new arithmetic to cast up reckonings, and keep accounts in; besides a thousand other inconveniences’5 – certainly valid concerns.

Both sides in the debate accepted the fact that changing the quantity of money would have real effects. Isaac Newton, then Master of the Mint, accepted the case for devaluation, arguing that if the coinage was revalued, as Locke wanted it to be, the money supply would fall, resulting in trade depression: fixed costs required flexible money. Locke, too, understood that halving the money supply would lead either to the halving of output and employment or a halving of wages, prices and rents, though he did not say which. More important to him was the thought that devaluation would lead to inflation. Inflation, by reducing the real burden of debt, would defraud creditors.

Locke won the day. Parliament ordered that clipped coins be handed in to the mint by a due date, the seller receiving (fewer) heavy-weight coins in return. The result was chaos. Since their revaluation took much of the existing coinage out of circulation, it resulted in an ‘immediate and asphyxiating coin shortage’.6 The bullion price of silver remained obstinately higher than the new mint price, so many of the new coins were exported. Those shopkeepers left holding the light coins rioted. Prices fell, business confidence collapsed, trade contracted. Within a generation so much silver had disappeared from circulation that the silver standard had to be replaced by the gold standard.

The recoinage crisis did lead to two permanent innovations in monetary policy. The Bank of England was set up in 1694 with the authority to issue notes. The Jacobean state was, in the words of Gladstone, ‘a fraudulent bankrupt’, which had to offer special inducements to get anyone with money to lend to it. These inducements were enshrined in the Bank’s first charter. The proprietors were given a monopoly of lending to the government, in return for 8 per cent interest, with the loans secured on earmarked revenues. (Locke saw an independent Bank of England as a critical bulwark for constitutional monarchy.)

Secondly, in 1717 Newton, as Master of the Mint, fixed the value of the pound at £3 17s 10½d per standard ounce of 22 carat gold, equivalent to a fine gold price of just under £4 4s 11½d. The Bank was obliged to convert its notes into gold on demand at this price. This remained sterling’s gold price for two hundred years, except for its suspension in the Napoleonic wars. Sound money triumphed, and the record was one of long-run price stability; between 1717 and the First World War, the average annual rate of inflation was just 0.53 per cent. But there were considerable short-run fluctuations; the average magnitude of annual price changes was 4.42 per cent.7

The establishment of the Bank of England and Newton’s rule made it much safer to lend to the state. The superior ability of the British state to mobilize the funds of its subjects for war was an important factor in its victories over France (a much more populous country) in the eighteenth century. A new social contract came into existence: merchants would lend to the state provided the state so conducted its affairs that its promises to pay were credible. As we shall see, this contract was the monetary counterpart of the fiscal contract whereby Parliament granted the government supply for approved purposes, including war, on condition that it balanced its budget in peacetime.

For the first time the British state was in a position to issue longterm debt. Its 3% Consols (consolidated debt raised on the revenues of the kingdom) were treated as liquid reserves by the banks, and over time became the safest form of security-holding for the new class of rentier bourgeoisie. The superior credibility of sterling would make it, over time, the world’s main vehicular currency for trade and payments: sterling, being ‘as good as gold’, minimized the need for gold transfers.

Older theorists had recognized that the standard of value was a political question, because it decides the distribution of wealth, income and the risks of uncertainty. Locke’s followers successfully insisted that it had to be fixed to avoid economic and, therefore, social disruption. Like all social scientific analysis that claims to reduce the political to the natural, it was largely a cover for vested interest.8

In the nineteenth century there were three grand discussions of monetary policy: the bullionist versus ‘real bills’ controversy from 1797 to 1821; the Currency School versus the Banking School debate of the 1840s; and the bimetallist controversy of the 1880s and 90s. British economists and bankers led the first two; bimetallism was an American cause. The focus of the first two debates was on the causes of inflation. This reflected – as it still does – the long-standing bias in monetary theory to treat inflation (‘too much money’) as the cause of most economic evils. On this view, the prelude to a crisis was the over-issue of money by governments and/or banks, feeding speculative bubbles that were bound to collapse. Thus, deflation was viewed as an inevitable consequence of the collapse of the inflationary boom. By the mid-1800s, the gold standard had triumphed as the indispensable anti-inflationary anchor, for the reason given by Locke and repeated by Adam Smith: provided the currency was firmly linked to gold, gold’s natural scarcity would stop any over-issue of money. But no sooner had the gold standard won the anti-inflationary battle than it was itself challenged, at the end of the century, by those who started to argue that scarcity of gold was a major defect in the system, because this prevented an expansion of the money supply in line with the growth of production. This set the scene for the monetary reformers to advocate cutting the link between money and gold altogether.

Running through the debates, but by no means clearly, was the question of the relationship of money to the economy. Both those who wanted a ‘hard’ currency to stop inflation and those who wanted a more ‘elastic’ currency to accommodate business and population growth, believed that the money supply was independent of the real economy of production and trade, and could therefore ‘get out of order’. The alternative claim that money, being created by bank loans and liquidated by their repayment, could neither exceed nor fall short of business conditions, while popular among businessmen and some bankers, was rejected by the professors of political economy as false reasoning: political economy taught that money, while it facilitates barter, can be a veil which hides from the eye the true value of the goods being traded. Therefore money could not be assumed to be automatically proportioned to real economic need: it had to be kept proportional by rules governing its issue.

The first of the debates came about as the result of the Napoleonic wars. War brought heavy military outlays, at home and abroad. In 1797, the Prime Minister William Pitt authorized the Bank of England to suspend the convertibility of the Bank’s notes into gold, as gold drained out of the country. The exchange rate of the pound against other currencies immediately dropped by 20 per cent. Gold was hoarded, causing the price of gold bullion to rise. The government resorted to printing notes to offset the fall in prices and to pay for ever-enlarging expenditure. The national debt soared to 260 per cent of GDP.9

The suspension of convertibility coincided with increases in agricultural prices. The average price for a ‘Winchester quarter’ (eight Winchester bushels, or just under a quarter of a ton) of wheat, for example, rose from 45s 9d in 1780–89 to 106s 2d in 1810–13.

The inflationary boom raised directly the question of the direction of causation. Did more paper money cause prices to be higher? Or did higher prices cause more money to be produced?

In The High Price of Bullion (1810), David Ricardo blamed the Bank of England for issuing more paper money than the economy could usefully absorb. Prices, he argued, would go up, and the exchange rate down, ‘to the same amount’ as the increase in money. The over-issue of money, in turn, had provided people with the means to buy government debt, issuance of which would have been impossible had the Bank not been relieved of its obligation to convert its liabilities into gold. Ricardo stated that ‘the necessity which the Bank felt itself under to guard the safety of its establishment [gold reserve], therefore, always prevented, before the restriction from paying in specie [i.e. the suspension of convertibility], a too lavish issue of paper money’.10 Once the gold convertibility obligation had been removed, the Bank’s directors were ‘no longer bound by “fears for the safety of their establishment” to limit the quantity of their notes to that sum which should keep them of the same value as the coin which they represent’.11 Ricardo went further, arguing that without a gold check there might be ‘no amount of money’ which banks ‘might not lend’.12 The ever-present danger of over-issue required convertibility into gold. From the Bullionist argument sprang an idea that was to be central to the modern quantity theory of money: the stock of money could be effectively regulated through the control of a narrowly defined monetary base.13 The prescription that it should be so controlled was the essence of the doctrine of sound money.

In its defence against Ricardo’s charges, the Bank of England denied that its policy had caused the depreciation of the pound: banks had simply lent, as always, on the basis of good security; this included the Bank of England’s loans to the government. The inflation was caused by the rise in agricultural prices following poor harvests and by the government’s claims on national resources to fight the war. The falling exchange rate was partly a consequence of the extra food imports that the crop failures required, and partly a result of the outflow of funds to cover the subsidies to Britain’s foreign allies. Neither was the consequence of any ‘over-issue’ of notes by the Bank of England.

In making this case, the Bank of England promoted the ‘real bills’ doctrine. The Bank, explained the Governor, ‘never force a note into circulation, and there will not remain a note in circulation more than the immediate wants of the public require’. The Bank’s lending, secured by ‘real bills’ (collateral), was self-liquidating on completion of the projects which gave rise to the asset: a theory known as the ‘law of reflux’.14 Ricardo attacked the real bills doctrine on the ground that ‘real capital’ could be created only by saving, not by credit: a claim notably revived by Hayek and the Austrian School in our own day.

Henry Thornton’s attack on the real bills doctrine was superior to Ricardo’s. As he pointed out in his Enquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain (1802), the Bank’s argument had a major technical weakness. It assumed that the issue of bills was independent of the price at which they were discounted, a price which lay in the power of the Bank of England to regulate. In fact, economic activity was jointly determined by the demand for credit and the price of credit. But Thornton failed to spot two other flaws in the real bills doctrine. The Bank never explained what determines the ‘needs of trade’ – lurking in the real bills doctrine is an assumption of full employment. And the Bank failed to distinguish productive investment from speculation.15

Thornton was the most remarkable monetary theorist of the early nineteenth century. To Smith and Ricardo, the rate of interest played no part in determining the quantity of money, the money rate of interest being merely a ‘shadow of the “rate of profit” on real capital’.16 Thornton was the first to distinguish between the rate of interest as the price earned from lending money, and the rate of profit earned on capital investment. He therefore anticipated Wicksell in appreciating that the supply of money is determined by the interaction of the ‘current rate of mercantile profit’ with the market rate of interest.17 He was the first to describe the cumulative process of credit creation. The only control the central bank had over the quantity of money was to ‘limit its paper by means of the price at which it lends’.18 By setting a ‘bank rate’, the central bank could control the interest rate structure and thus the quantity of domestic credit.

Ricardo won the argument, because his explanation of inflation was creditor-friendly, and because the Bank was unable properly to explain the inflation that had followed the suspension of convertibility. The 1810 Bullion Report concluded that a ‘rise in the market price of gold above its mint price will take place if the local currency of this particular country, being no longer convertible into gold, should at any time be issued to excess’; the Bank, a private corporation, had failed to restrict its loans out of concern for its own profits.19 It was vain to think that the issue of a discretionary currency could be limited. The Report advocated an immediate resumption of convertibility of notes into gold at the pre-suspension price set by Isaac Newton a hundred years previously – ‘the only true, intelligible, and adequate standard of value’, as Robert Peel called it.20 Bank lending would be automatically curtailed; most of the notes issued in the period of suspension would simply cease to be legal tender. (The equivalent of the recoining of 1697.) Wisely, however, the House of Commons decided to delay implementation of its findings.

The end of the Napoleonic wars was followed by deflation and depression. The depression was caused not so much by the resumption of gold convertibility itself as by anticipation of it. The depression lasted twenty years, with the commodity price level falling 59 per cent between 1809 and 1849.21Agriculture was hit by renewed competition; arms manufacturers round Birmingham went bust. Political reactions to the deflation of prices included the radical Chartist movement in Britain and revolutions on the Continent. Orthodoxy, wedded to the commodity theory of money, attributed the fall in prices to a decline in the production of precious metals. But Thomas Attwood, a Birmingham banker, attributed the depression partly to the curtailment of state orders for arms. The exchange rate, he said, should only be stabilized after five to ten years of full employment. He urged the need for ‘accommodating our coinage to man, and not man to our coinage’;22 Britain should have a paper currency that was not tied to gold. Ricardo rejected Attwood’s arguments. ‘A currency may be considered as perfect, of which the standard is invariable, which always conforms to that standard, and in the use of which the utmost economy is practised.’23 Gold convertibility was restored in 1821. All this was a rehearsal of the debate which followed the end of the First World War, with the arguments and sequence of policies being almost identical.

Jacob Viner noted that Ricardo was blind to the short-run consequences of the policies he advocated. The Ricardian vice of abstraction from reality is beautifully illustrated by an exchange between Ricardo and his friend Thomas Malthus in January 1821 concerning the causes and consequences of the great depression in trade which had followed the Napoleonic wars. Ricardo accused Malthus of having ‘always in your mind the immediate and temporary effects of particular changes – whereas I put these immediate and temporary effects quite aside, and fix my whole attention on the permanent state of things which result from them’.24 Malthus admitted his tendency to ‘refer frequently to things as they are, as the only way of making one’s writing useful to society’ and of avoiding the ‘errors of the tailors of Laputa, and by a slight mistake at the outset arrive at conclusions most distant from the truth’.

This argument has run through economics, with Keynes taking up Malthus’s baton in the 1920s. As we will have further reason to emphasize, the short-run/long-run distinction has had a baleful effect on economics and economic policy. It has served to protect its longrun equilibrium thinking from the assault of disruptions, and to justify policies of inflicting pain on populations. One may feel that insistence on the need for short-run pain (e.g. austerity) for the sake of long-run gain, when the short-run can last decades and the long-run may never happen, testifies to a refined intellectual sadism.

The second of the grand monetary discussions of the 1800s was really a continuation of the first, but this time in the context of the restored gold standard and a business cycle connected with railway speculation. The Currency School, led by Lord Overstone, George Norman and Robert Torrens, expanded on the arguments of the Bullionists. While the Bullionists regarded convertibility into gold as a sufficient safeguard against the over-issue of notes, the Currency School argued that the drain of gold from the central bank wouldn’t immediately curtail issue of credit by the country banks, who were not subject to specie reserve requirements.25 The Bank of England had to have control over the whole note issue in order for domestic currency to behave like a metallic currency.

The Banking School pooh-poohed these arguments. Their spokesmen, Thomas Tooke, John Fullarton and James Wilson, argued that the policies of the Currency School imposed undesirable limitations on the central bank’s ability to adjust the quantity of money to changes in the demand for money. Tooke claimed to show that in the period 1762 to 1856 fluctuations in the note issue had followed fluctuations in business activity, not preceded them. Fullarton said that commercial transactions didn’t require a prior issue of money, but could be carried out by book credits transferable by cheque.26

Despite the objections raised by the Banking School, the Currency School won the day, because it provided a practical foundation for maintaining the gold standard. The Bank Charter Act of 1844 gave the Bank of England a legal monopoly of note-issue in England and Wales.27 New notes (or cheques) could be issued only if the Bank received an equivalent amount in gold. The ‘fiduciary issue’ – the part of the note-issue not backed by gold – was to be frozen at its 1844 level. The purpose of the Act, as stated by one of its backers, ‘was to make the currency, consisting of a certain proportion of paper and gold, fluctuate precisely as if the currency were entirely metallic’ – i.e. to fluctuate very little.28

Yet the Currency School’s triumph was less overwhelming than it seemed. In exceptional circumstances, the government retained the power to suspend the Act. Moreover, it was in the second half of the nineteenth century that the Bank of England started to develop its modern function as ‘lender of last resort’ to the banking system, a duty codified in Walter Bagehot’s 1873 classic, Lombard Street. Bagehot argued that it was the Bank’s duty to keep large-enough reserves to be able, in a crisis, to lend freely to all solvent banks at a very high rate of interest. Widely resisted at the time on the high ground of ‘moral hazard’, it led to the Bank organizing the rescue of Barings in 1890. This was the doctrine that the US Federal Reserve signally failed to apply in the Lehman Brothers crisis of September 2008, and which the European Central Bank was debarred by law from applying in the European banking crisis that followed.

Until the early 1870s, the international monetary system was bimetallic: some countries, like Britain, were on a gold standard, and other countries, like France, were on both gold and silver standards. The customary ratio of exchange between gold and silver was 1:15. But both France (in 1873) and America (in 1879) de-monetized silver, and went on to a full gold standard.29 Other states aspiring to be ‘first class’ countries with first class credit ratings also joined the gold standard.30 By the 1880s the gold standard had gone international.

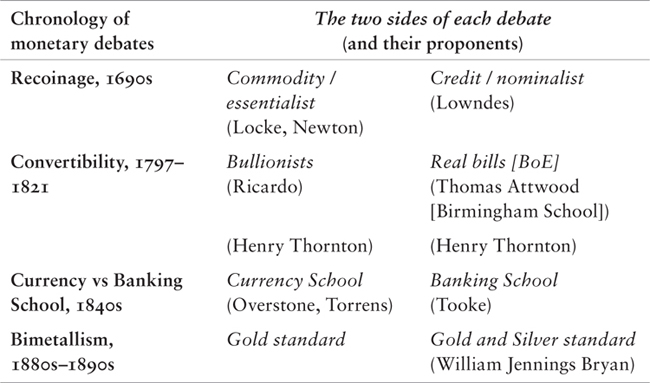

Figure 3. The price history of Britain31

The increased trust in international money helped trigger the first age of globalization.

But no sooner had the gold standard won its victory than its position was undermined, by the continuous fall in wholesale prices which lasted from 1873 to 1896. This was known as the Great Depression, before the second one usurped its place in the history of economic misfortunes.

It was not a depression in the modern sense, rather a lingering deflationary disease, punctuated by bursts of excitement. Nevertheless, it started the third grand monetary discussion. There was much debate about whether the causes of the deflation were monetary or ‘real’. Just as it had explained the mid-century’s rising prices by the Californian and Australian gold discoveries, orthodoxy now explained the fall in prices by the exhaustion of existing mines and the de-monetization of silver. The successors of the Banking School attributed it, instead, to the collapse in agricultural prices following the fall in transport costs and increased supply from the Americas. For instance, the English statistician Robert Giffen argued that ‘it is the range of prices as part of a general economic condition which helps determine the quantity of money in use, and not the quantity of money in use that determines prices’.32

The orthodox school won the analytical battle, as it had ever since the time of Jean Bodin. Falling prices were due to scarcity of money. But by the same token the role of gold as money came under attack. Statesmen and economists had united in support of the gold standard and currency convertibility, because they regarded convertibility as the only safeguard against inflation. Yet the gold standard was now exposed as an important cause of deflation.

Bimetallism – a monetary system in which both gold and silver would be legal tender, with a fixed rate of exchange between them – won its greatest popular support in the United States. American farmers, with loans denominated in gold, were squeezed by falling prices which raised the real price of their debts. They agitated for a reintroduction of a silver-backed currency to expand the money supply and stave off deflation. William Jennings Bryan, the (unsuccessful) Democratic presidential candidate of 1896, declared: ‘you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold’. Bimetallism was championed by Bryan and others as a way to increase the money supply. The bimetallic cause lost not just because of bimetallic currency’s inherent unsteadiness – it was likened by the economist Irving Fisher to ‘two tipsy men locking arms’33 – but because cheaper ways of mining gold, enabling the development of South African gold mines, relieved the gold shortage.

But the analytical debate was far from over. To prevent monetary shocks it was necessary for gold production to keep pace with productivity growth. However, new gold production was very imperfectly correlated with a growing economic system’s need for money. Central banks started to see their function as to smooth out price cycles, raising interest rates and hoarding gold to dampen price rises, and lowering them and allowing reserves to fall to check downward pressure. But would not a better way to secure an elastic currency be to cut the link between money and the precious metals once and for all? The time had come to free monetary conditions from erratic gold movements.

The gold standard linked the volume of a country’s currency to its gold stock. Its essential feature was that all the domestic currencies of the trading partners could be converted into gold at a fixed price. Currencies were just names for different weights of gold; they were ‘as good as gold’ because they could be converted into gold.34 This meant they could be freely traded with each other. A system of this kind required both freedom for individuals to import and export gold and a set of rules relating the quantity of domestic money in circulation to the amount of the central bank’s gold reserve. Without freedom to import and export gold, gold could not serve as an international means of payment; without rules to limit the issue of paper money to the quantity of their gold reserves, central banks could easily run out of gold.

The gold standard was designed to force governments and countries to ‘live within their means’. The fact that it put money creation beyond the reach of governments was widely seen as its chief virtue. As Herbert Hoover put it in 1933: ‘we have gold because we cannot trust governments’. The gold standard also forced countries to live within their means by depriving them of gold if they didn’t. As David Hume had pointed out, a country which imported more than it exported would, literally, run out of money. It could, of course, borrow, but loans had to be repaid. Gold was the risk-free collateral for loans, the guarantee against default. For a country to be ‘on gold’ – to commit to paying its debts in gold – was the smooth path to borrowing; the nineteenth-century equivalent of an AAA-rating. The gold standard was well suited to the interests of creditors, because it prevented inflation being used as a method of reducing the real burden of debts. Its disciplines were onerous and it was thought that only ‘first class’ countries could accept them. Britain was first to link its currency to gold in 1721, but by the end of the 1800s all ‘civilized’ countries had followed suit.

The great mystery of nineteenth-century monetary history is the success of the gold standard. It was designed to keep both governments and countries from over-spending and did, on the whole, work. ‘Civilized’ countries no longer defaulted on their debts. But a correlation is not a cause. The question is: was it the rules of the gold standard which kept money ‘in order’? Or did underlying conditions make it relatively easy to follow the rules? Exactly the same question would arise in the Great Moderation years of the 1990s and 2000s: was it central bank inflation-targeting which kept inflation low, or was it what the Governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King described as a ‘nice’ environment?

David Hume’s price–specie–flow mechanism originated the story of how the gold standard was supposed to work. Domestic prices would fall in gold-losing countries and rise in gold-gaining countries, restoring equilibrium in their trade balances. This left ‘central bankers [with] little to do besides issuing or retiring domestic currency as the level of gold in their vaults fluctuated’.35

In fact, gold flows were only a tiny element in the nineteenth-century adjustment mechanism. To settle trade imbalances by shipping bullion round the world was much too costly. Nor did individual country prices vary inversely with each other. They tended to move in tandem.

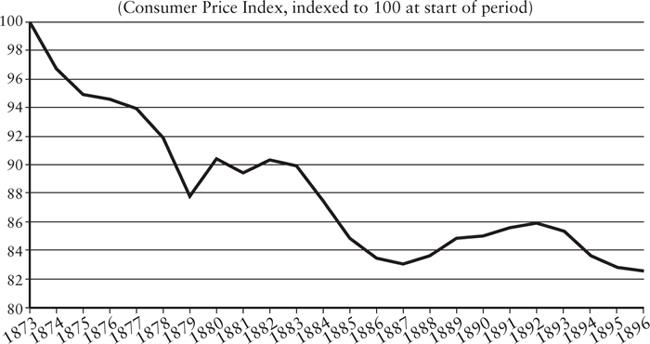

If countries didn’t play by the Hume rules, perhaps they played by the Cunliffe rules? The influential Cunliffe Report of 1918 presented a twostage model of adjustment which had been extracted from the history of the gold standard (Figure 4). In the first stage, the drain from the central bank’s gold reserves (G) causes it to raise Bank Rate (r) – the rate of interest at which it lends money to its member banks. This is adjustment 1 in the diagram. The result is a capital inflow sufficient to finance any temporary – typically seasonal – deficit on the trade account. Bank Rate can then come down again (adjustment 4 in the diagram).

However, if the adverse current account balance persists after adjustment 1 then the second stage of Cunliffe’s model, involving two further adjustments (2 and 3), will come into play before the interest rate goes back down (adjustment 4). In the second adjustment, the higher interest rates cause a drop in aggregate demand for domestic goods (AD), which exerts downward pressure on the price level of domestic goods (P) and on the level of output (Y), along the aggregate supply curve (AS). The drop in prices then leads aggregate demand for domestic goods and for the country’s exports to shift back up, leading to a higher level of output and prices (adjustment 3). This, in turn, prompts gold outflows to reverse, which eventually causes Bank Rate to drop back down to its original level (adjustment 4).

Figure 4. The Cunliffe Mechanismr

The Cunliffe model improves on the simple Hume account by treating Bank Rate, not gold flows, as the operational adjustment tool, and by emphasizing the difference between short-run and long-run adjustment mechanisms. That temporary imbalances under the gold standard were financed by short-term borrowing, not gold flows, is clear; but there is little evidence of the price and income changes which were supposed to bring about the permanent adjustment of imports and exports. Current account imbalances tended to persist.36 So what was the gold standard’s secret?

Monetary historians such as Barry Eichengreen emphasize the importance of the commitment to convertibility.37 This was the moral rule of the system. ‘Promises must be kept,’ thundered the bankers; to ‘go off’ gold was a breach of faith. Like marriage vows, promises of fidelity to gold were designed to keep doubt at bay, because it was recognized that humans were frail and that the more their pledges were treated as sacred, the less likely they were to be broken.

There is obviously something in this. Commitment to convertibility eliminated, or greatly reduced, exchange risk and this facilitated the financing, hence expansion, of trade. But it is also true that in the heyday of its authority, no onerous adjustments of the Hume or Cunliffe type were needed; had they been, the gold standard might well have collapsed much sooner. Adjustment was certainly eased by the fact that in the nineteenth century new discoveries of gold, as well as financial innovation, occurred frequently enough to keep pace with production, keeping the price level stable. More importantly, the direction and character of the trade, capital and population flows in this, the first age of globalization, obviated any systemic threat of system collapse. To put it simply: debtors were not subjected to sufficient strain ex ante to force painful adjustment ex post. Virtue was relatively cheap.38

Five different aspects of the incentive to virtue can be noted:

1. Barry Eichengreen has argued that the commitment to currency convertibility was not endangered by democracy, since suffrage was limited and trade unions were weak.39 This implies a tolerance of unemployment. In fact, cheap grain imports from the New World caused huge unemployment among agricultural labourers in Europe from the 1880s onward, but it did not persist. This is because the unemployed in Europe got, not on their bikes, but on ships to the New World. Between 1881 and 1915, there was a net emigration of 32 million people from Western and Central Europe, about 15 per cent of its population, most of whom went to the thinly populated New World. The nonpersistence of unemployment fed the belief of the classical economists that, given flexible labour markets, unemployment would be transient. But this particular type of labour flexibility depended on having excess supplies of labour in one part of the world and excess supplies of land in another.

2. The predominantly commodity structure of international trade, and the low share of non-tradable services in domestic GDPs, meant that, on the whole, the law of one price prevailed, limiting the need for price adjustment. The wedge between domestic and foreign prices, which made the adjustment problem so politically fraught in the twentieth century, was much less pronounced before 1914.

3. International trade was relatively non-competitive. The massive reduction in transport costs enabled a long-distance trade to build up between the core European countries and their overseas or transcontinental peripheries. To put it at its simplest, capital goods from Western Europe built the railways and harbours in the peripheries from which were transported foodstuffs and raw materials to Western Europe. The fact that most international trade resulted in a complementary exchange of manufactures for raw materials reduced the pressure on individual core countries to ‘be competitive’.

4. Current accounts were balanced by capital flows. The goldstandard world was divided into a developed centre and developing peripheries. From the 1870s to 1914 an increasing volume of capital flowed from the ‘core’ of developed countries to the ‘periphery’ of developing ones. The growth of capital exports coincided with, and was facilitated by, the incorporation of the main trading countries into the gold-standard system between 1870 and 1900. Sovereign states joined the gold standard independently; they made their colonies and dependencies part of their monetary systems. The gold standard offered investors a cheap and efficient credit-rating agency. Provided they practised monetary discipline, balanced their budgets and were free of arbitrary regime change, developing countries could go on borrowing to finance their ‘catch-up’ at low interest rates.

5. The gold standard worked in tandem with empire. The golden age of the gold standard was also the golden age of imperialism. Imperialism cemented globalization. Between 1880 and 1900 the whole of Africa and parts of Asia were incorporated into the European empires. Thus the spread of the gold standard coincided with the political division of the world into sovereign and dependent states. A high proportion of European loans went to colonies and semi-colonial dependencies. The colonies provided sheltered markets for the exports of the colonial power and important sources of their foodstuffs and raw materials. Exports of capital tended to be directly tied to the exports of machinery and manufactures from the lending country, with the colonist following in the footsteps of the trader and investor.

By 1870, 70 per cent of British foreign investment was going to its empire, whose territories were, in effect, on a sterling standard. Even in ‘independent’ Latin America, creditors could enforce their will because state borrowers were weak sovereigns. Thus, imperialism, formal and informal, lowered the cost of development capital. Lenin would later see imperial rivalry as the seedbed of war, but before 1914 imperialism was the means by which the developing world was enabled to accumulate capital goods. It was the treble outward movement of trade, investment and population under the imperial umbrella which gave an upward thrust to global economic activity.

These structural supports of the international gold standard are widely recognized. More debatable is the role of Great Britain in sustaining the system. The gold standard has been called a ‘Britishmanaged’ or ‘sterling’ standard; Keynes called London ‘the conductor of the international orchestra’. The argument has been between those, like Eichengreen, who argue that the gold standard was a cooperatively managed system, and those, like Kindleberger, who claimed that it was a hegemonic system, with Britain as the hegemon.40

Eichengreen is undoubtedly right to say that, as far as Europe is concerned, the system rested on central bank co-operation, made possible by the relative absence of political conflict. Despite all the tensions, there wasn’t a major war in Europe from 1871 to 1914, a period of forty-three years. However, Britain did play a leadership role, not just because of the global reach of the British Empire, but also – and connected with this – because of the dominant position of Britain in international trade, finance and migration. Over the course of this period, it provided around two-fifths of the world’s capital exports;41 in 1900, Britain took just under a quarter of the world’s imports;42 the City of London was the world’s undisputed financial centre, ‘through which flowed all the transfers between borrowers and lenders, creditors and debtors, and buyers and sellers that were not internal to a single country’;43 and much of the New World was populated by emigrants from the British Isles.

These features, according to Charles Kindleberger, enabled Britain to take on the support of the global system in periods of adversity ‘by accepting its redundant commodities, maintaining a flow of investment capital, and discounting its paper’, the three essential countercyclical services.44 The importance of the Kindleberger thesis is that it explains better than any other how the adjustment problem – who adjusts to whom? – was solved under the classic gold standard. Broadly speaking, it was the chief creditor country, Britain, which took on the onus of adjustment. Britain, or more precisely the City of London, provided the world with a surrogate sovereign, akin to an international central authority, offering some of the services of a world government or bank. (The United States would take on this role after the Second World War.)

For example, a small rise in Bank Rate would attract foreign funds to London at will. Britain’s uniquely maintained free trade policy meant that it could run commodity import surpluses when the terms of trade moved in its favour, and beef up capital exports and exports of people when the terms of trade turned against it. These were crucial balancing functions.45

Britain’s fiscal constitution reinforced sterling’s hegemonic role. The idea that ‘the pound was as good as gold’ expressed not a mechanical link between gold and currency, but the belief that the British state would so conduct its fiscal affairs that the purchasing power of a pound note would remain stable.

The first age of globalization was not the frictionless paradise depicted in free trade models. The average height of tariff barriers rose in the forty years before the First World War, as competitive trade became a larger fraction of total trade. Britain allowed its arable farming to be destroyed by cheap imports from the Americas: France and Germany protected theirs. Banks tended to hoard gold if it was abundant, allowing their reserves to rise. The gold standard often cracked at the peripheries, as Latin American and southern European governments defaulted on their bonds: Greece was in default for much of the time. At such times capital flows turned into capital flight, and new loans were made conditional on guaranteed revenue streams.

Nevertheless, Cairncross’s summary is apt:

The conditions of the period seemed to work together for the unstable maintenance of stability. A qualified stability admittedly, for there were repeated and severe depressions; and an insecure stability, since it required the constant opening of new fields for investment and the free movement and rapid increase of population which these openings encouraged; but none the less, by interwar standards, stability.46