‘For it is the part of man to be master, not slave, of nature, and not least in a sphere of such extraordinary significance as that of monetary influences.’

Knut Wicksell, 18981

‘The theory of the interest rate mechanism is the center of the confusion in modern macroeconomics. Not all issues in contention originate here. But the inconclusive quarrels . . . largely do stem from this source.’

Axel Leijonhufvud, 19792

In the twentieth century, gold lost the battle to control money. There was either too much or too little of it. In the first case it was blamed for inflation; in the second, for deflation and unemployment. Instead of control by gold, there would be control by experts in the central bank, equipped with ‘scientific’ theory. The battle between the supporters of gold and the monetary reformers dominated the monetary history of the first third of the new century.

The reformers took their stand on a mathematical version of the Quantity Theory of Money (hereafter QTM). The QTM is the first theory of macroeconomics; it is also very muddled. On the one hand it depicts money as being a paltry thing, hardly worth writing about; on the other, it sees it as a mighty monster, which has to be kept under lock and key if it is not to wreak havoc. These two views are inconsistent, the cognitive dissonance arising from trying to account for the real-world impact of monetary disturbances with an analytic structure that abstracts from the use of money. The realization that money needs to be treated as an independent factor of production had to wait until the coming of Keynes. And even Keynes had to emancipate himself from the quantity theory before he felt he could accurately analyse the economic problem to which money gave rise.

The key belief of the pre-1914 monetary reformers was that instability in the price level generates not just economic but social instability, by producing unanticipated shifts in the level of activity and distribution of wealth. The aim of economic policy ought therefore to be price stability. This policy prescription rested on the belief that, in a system of fiat money, the central bank has ultimate control over the quantity of money in circulation. If the central bank can control the quantity of money, either directly or indirectly, it has the power to make the price level what it wants it to be. And if it can make the price level what it wants it to be, it can control economic fluctuations. Thus the QTM went beyond explanation to prescription. It was intended for use. It was the scientific cure for price fluctuations, which were regarded as the main cause of business fluctuations.

The two principal versions of the QTM are associated with the American economist Irving Fisher (1867–1947) and the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell (1851–1926), respectively. For Fisher, changes in the price level are directly caused by the expansion and contraction of central bank or ‘narrow’ money. Wicksell, while accepting the causal relationship between money and prices, argued that the money supply was created by commercial banks in the course of making loans; and that the central bank could exercise indirect control only by regulating the price of loans (interest rate). These two versions of the QTM have contested the ground of monetary theory ever since, with many doubting whether Wicksell was really a quantity theorist at all. The American version of the QTM derives from Fisher via Milton Friedman; the European version is more Wicksellian. Keynes was a Wicksellian until the early 1930s, when he broke with the QTM altogether.

In 1911, Fisher produced his famous equation of exchange:

MV = PT

On the left we have M for the money supply and V for velocity of circulation – the number of times a unit of money changes hands in a period of time. P is the weighted average of all prices and T the sum of all transactions in the specified period. (For a technical discussion, see Appendix 3.1, p. 71.)

The equation of exchange is true by definition. If the number of dollars in the economy is $5 million, and each dollar changes hands twenty times a year, then the total amount of money changing hands is $100 million. This, by definition, must equal the total value of transactions in the economy. In plain English, ‘things cost what is paid for them’. But this tells us nothing about causation.

Fisher turned his equation of exchange into a theory of the price level by assuming, first, that the price level is ‘normally the one absolutely passive element in the equation of exchange’3 (i.e. money is exogenous), and secondly, that the velocity of money and the volume of transactions (V and T respectively) stay the same in the relevant period. Given the ground rules of the discussion, ‘there is no possible escape from the conclusion that a change in the quantity of money (M) must normally cause a proportional change in the price level’.4

Fisher then proceeded to test the logic empirically. Studying the two-thirds rise in US prices between 1896 and 1909, he concluded that most of it could be explained by a doubling in the quantity of money (due to increased gold mining), a tripling of deposits (due to increased business activity) and a slight increase in velocity (due to a growing concentration of people in cities). That money supply increased ahead of prices, while velocity stayed relatively constant, heavily shaped Fisher’s conclusion that but for the growth of the money supply, the price level would have gone up only by about half the amount it did.5

Fisher’s model exhibited the classic form of model construction: a hypothesis, a presumed set of relationships linking the hypothesis to the other model variables, the logical conclusion, and the empirical testing of the conclusion.

There was also the ‘Cambridge’ equation, derived from Alfred Marshall:6

M = kPT

Here k, the demand for cash to hold, is the reciprocal of V, its rate of turnover.

The Fisher and Cambridge statements of the QTM both present a transactional view of money (deriving from the barter theory considered in Chapter 1). But there is a subtle difference of emphasis. The Cambridge economist Marshall introduced marginal utility into the demand for cash function: people ‘balance at the margin’ the advantage of holding money and buying investments. But this was a purely decorative concession to the new-fangled marginal productivity theory of value. It had no operational significance for his own monetary theory. The Marshallian k is merely a ‘temporary abode of purchasing power’. He gave as an example keeping enough money in the bank to pay the weekly wages. He would also have recognized holding reserves for contingencies. He did not consider these to be major leakages from the spending stream. So, for control purposes, the two equations came to the same thing, confirming the view that people acquired money only to spend it.

How does new money get into the system? If the QTM is to provide a rationale for monetary policy, the answer to this question is important. Fisher (like Marshall) assumed that individuals have a ‘desired ratio of money to expenditure’, this amount being given by ‘habit and convenience’.7 He then argued: ‘If some mysterious Santa Claus suddenly doubles the amount [of money] in the possession of each individual’, the recipients would spend the excess money in buying goods of various kinds, leading to a ‘sudden briskness in trade’ as people try to restore their money–expenditure ratio. But the only way individuals can get rid of money is by handing it over to other people; society as a whole cannot be rid of the extra money. Thus, ‘the effort to get rid of [surplus cash] . . . will continue until prices have reached a sufficiently high level’; that is, until the increased spending of the community would cause prices to double, thus restoring the real value of their cash balances. This is the source of Friedman’s idea of ‘helicopter money’. In technical terms, the demand for ‘real balances’ is brought into equality with the increased supply of money by a change in the price level.8

Evidently, the simple Fisher story needs no ‘transmission mechanism’: Santa Claus (or the helicopter) drops the money straight into the pockets of potential consumers. The need to specify a transmission mechanism arises from the existence of a banking system. Marshall explicitly assumes that the new money comes through the banks, via its effect on interest rates. The first effect of an influx of gold into the banking system, he says, is to lower interest rates. This increases the demand for loans. The increased demand for loans will ‘carry off’ the larger supply of loanable funds available. The spending of these loans will cause prices to rise until, with the extra funds being exhausted, interest rates rise again.9 This is known today as the ‘bank lending channel’. However, interest rates play no independent part in determining the quantity of money: they are merely the means by which, in a banking system, the helicopter money gets into the pockets of those who will spend it. This is because Fisher and Marshall still thought of money as cash rather than credit: it was the injection of cash which determined the interest rate structure.

Both the Fisher and Cambridge versions assume a stable money multiplier, that is, a stable ratio of reserves to deposits.10 Similarly, they presuppose a stable velocity of money, unaffected by changes in its supply. In holding V constant, they ruled out the possibility of fluctuations in the demand for money.

However, like previous monetary theorists, Fisher did distinguish between the short-run and long-run effects of a change in the quantity of money. If everyone adjusted instantly and equi-proportionally to a change in the money stock, money would affect only the price level. But relative prices don’t adjust instantly, because people don’t know what the new equilibrium price is – i.e. they are uncertain about how much prices will go up or how much they will fall.

It was a common observation that when the price level is rising (or as we would say today, when inflation is rising) people will spend their money faster; if it is falling (or expected to fall) they will hoard it. Thus Nassau Senior in 1819: ‘Everybody taxed his ingenuity to find employment for a currency of which the value evaporated from hour to hour. It was passed on as it was received, as if it burned everyone’s hands who touched it.’11 This had happened with French assignats in the 1790s. The reason is that rising prices impose an ‘inflation tax’ on the holders of existing currency notes: each note buys less than before. To avoid having to spend more money on their desired goods, holders of these notes increase the speed or velocity with which they spend them.

Falling prices have the reverse effect: people delay spending their cash, expecting to get their goods cheaper a little later. Marshall’s seemingly innocuous k, the proportion of their wealth which people hold in cash, rises and falls with ‘each turn of the tide in prices’. But the QTM is valid only if velocity stays constant. And velocity only stays the same if the price level resulting from the change in the money stock is perfectly foreseen. Thus, although the QTM comes out of that stable of thought which believes that money affects only prices and nothing else, policy based on the QTM was set the task of keeping prices stable to avoid arbitrary shifts in activity and distribution. Uncertain expectations enter the monetary story for the first time, with the management of expectations becoming an implicit part of monetary control.

Uncertainty about the future course of prices is Fisher’s explanation of the business cycle. In equilibrium, the quantity of money has a fixed ratio to bank deposits, and to the quantities and prices of goods offered for sale. In ‘periods of transition’, though, from one price level to another, these ratios vary, causing the real economy to malfunction. Fisher singled out the misbehaviour of the rate of interest as ‘largely responsible for . . . crises and depressions’.12 The nominal rate of interest doesn’t adjust quickly enough to changes in the quantity of money, causing the price level to ‘overshoot’ or ‘undershoot’, and consequently the real rate of interest (seen as the result of the price level changes) to stay either too low or too high for the equilibrium of saving and investment. In the upswing, falling real rates enable businessmen to make windfall profits; so bank deposits increase faster than the quantity of money, increasing the velocity of circulation, and driving interest rates still lower. There will be a temporary increase in trade and employment. Eventually banks are forced in self-defence to raise interest rates because they can no longer stand an abnormal expansion of their balance sheets. Rising nominal rates then bring about a crisis and depression, as loan portfolios contract, and velocity slows down; ‘the collapse of bank credit brought about by loss of confidence is the essential fact of every crisis’.13 Fisher’s ‘swing of a pendulum’ can last ten years. But these disturbances to the pre-existing equilibrium, while grave, have entirely monetary causes, and therefore monetary remedies. Fisher thus remained faithful to the classical dichotomy: the separation of monetary from ‘real’ events.

Fisher had a remedy. Pendulum swings in prices and trade can be avoided (or at least mitigated) by knowledge and policy. On the side of knowledge, Fisher anticipated the main point of the ‘rational expectations revolution’ sixty years later: if bankers had the correct model of the economy (the QTM) they would be able to anticipate price changes from knowledge of monetary data and adjust the quantity of loans promptly.

On the side of policy, a theoretically perfect solution to price fluctuations would be an inconvertible paper standard. Paper currency would be expanded in the same proportion to the increase in business activity.14 But unlimited power of note-issue would be subject to political manipulation, especially on behalf of the debtor class.15

To limit the discretion of the monetary authority, Fisher toyed with the idea of a tabular standard (price-indexed contracts), but in the end settled for the ‘compensated dollar’, a scheme to vary the quantity of notes obtainable for a unit of gold so as to keep their purchasing power steady. Instead of getting a fixed price of $20.67 for an ounce of gold, a person seeking to convert gold into dollars could get either more or fewer paper dollars for it, depending on whether the price of gold was rising or falling. As a counter to deflation, this was like the medieval practice of debasing the coinage, but now put forward as a scientific method of monetary management. Fisher pursued this project indefatigably for the rest of his life.

The rate of interest played no operative role in Fisher’s control system. Control of the price level was to be effected by varying the quantity of notes, with the rate of interest adjusting passively (though with a lag) to changes in bank reserves. Money was liable to play an independent disturbing role only in periods of transition, when the rate of price increases was uncertain. This was an additional reason for ensuring that the price level was kept stable.

The increasingly rigorous formulation of the QTM associated with Fisher made it clear even to quantity theorists that changes in monetary conditions had real and not just nominal effects. During the ‘transition periods’ from one price level equilibrium to another, interest rates, profits, wages and velocities would stray from their equilibrium values, thereby disturbing the proportionality theorem. Moreover, unforeseen changes in prices brought about arbitrary redistributions of wealth and income. Prevention was better than the cure of boom and bust.

Like Fisher, the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell was appalled by the social damage wrought by fluctuations in the price level. All monetary investigations, he wrote, ‘are ultimately concerned with creating and maintaining a monetary system which is reliable and elastic, in other words a medium of exchange whose purchasing power in relation to commodities changes either not at all or only very slowly in either direction’.16

Wicksell also identified himself as a quantity theorist, and agreed with Fisher about the QTM as applied to a purely cash economy – one where the only money in circulation is notes and coins. However, money in an economy with a developed banking system is mainly created by the banks, and it is disturbances to the credit system – to the supply of, and demand for, loans – not exogenous money shocks, which give rise to the business cycle. The business cycle is a ‘credit cycle’.

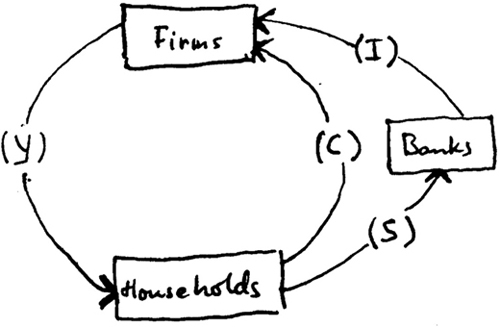

The banks have a double role in Wicksell’s model. On the one hand they are loan intermediaries between the savings of households and the investments of business. But they also supply credit to the business sector. The ‘circular flow’ thus consists of savings and credit, both flowing in and out of the banks.

Wicksell’s circular flow displays the now standard macroeconomic identity:

Figure 5. Leijonhufvud’s circular flow diagram17

where Y is output, C is consumption, I is investment and S is savings. In equilibrium, banks intermediate between the (real) savings of households and the (real) investment decisions of firms. In a period of rising prices, firms get both bank credit and household savings. By lending more to the business sector than flows in as savings from the household sector, the banking system will cause the circular flow to expand, and the price level to rise.

When banks are lending more than the public wishes to save, there is no check to the expansion of money and rise in prices. Wicksell asks us to imagine a giant bank that is the source of all loans and in which all the community’s money is deposited. In giving customer A a loan, the bank creates money out of nothing. When A spends the loan, he increases customer B’s deposits in the same bank, the spending of which increases customer C’s deposits, and so on. In other words, the first loan enables prices to rise without limit. As Wicksell said, the upward movement of money ‘creates its own draught’.18

The conclusion suggested by this thought experiment is that governments do not have direct control of the money supply; money in modern economies is created by commercial banks when they make loans.

Echoing Thornton, Wicksell reasoned that the expansion and contraction of credit (and thus the price level) can take place only if the market rate of interest deviates from the ‘natural’ rate, or what Wicksell calls the real rate of return on capital.

Now let us suppose that the banks and other lenders of money lend at a different rate of interest, either lower or higher, than that which corresponds to the current value of the natural rate of interest on capital. The economic equilibrium of the system is ipso facto disturbed. If prices remain unchanged, entrepreneurs will in the first instance obtain a surplus profit . . . over and above their real entrepreneur profit or wage. This will continue to accrue so long as the rate of interest remains in the same relative position. They will inevitably be induced to extend their businesses in order to exploit to the maximum extent the favourable turn of events. As a consequence, the demand for services, raw materials and goods in general will be increased, and the prices of commodities must rise.19

In this passage is to be found the source of Wicksell’s mistake. Highly original as Wicksell was, his roots were in the barter theory of exchange, in which banks simply intermediate between buyers and sellers. He thought that by raising and lowering the price of credit the central bank could make money ‘neutral’ in relation to the ‘real’ or ‘natural’ rate of interest on capital. But the ‘rate of interest on capital’ is just as much a money rate as is bank rate. The so-called natural rate is, as Keynes was later to insist, an expected rate, and the expectations were of a money return for a money outlay. There is no escape from the circle of money.

Nevertheless, Wicksell goes on to his conclusion that ‘the maintenance of a constant level of prices depends, other things being equal, on the maintenance of a certain rate of interest on loans’.20 This paved the way for modern monetary policy: monetary authorities should aim to keep the short-term interest rate equal to the estimated movements of the natural rate of interest on capital, plus an inflation target. Pre-2008 crash monetary policy was broadly Wicksellian.

Leijonhufvud summarizes Wicksell’s argument as follows:

i) the circular flow of money income and expenditures will expand if and only if there is an excess demand for commodities;

ii) ‘investment exceeds savings’ implies ‘excess demand for commodities’ and conversely;

iii) investment will exceed saving if and only if the banking system lengthens its balance sheet at a rate in excess of that which would just suffice to intermediate household saving;

iv) the economy will be on its real equilibrium growth path (capital accumulation path) if and only if savings equals investment;

v) the value of the interest rate that equates saving and investment at full employment is termed the ‘natural’ rate.21

Because Wicksell thought that changes in the ‘natural’ interest rate arise from real factors (such as wars, technological innovations, etc.), it is tempting to conclude that he was not a quantity theorist – that he thought that price movements were ultimately explained by changes in the real economy.

This is not how Wicksell saw himself. Real shocks could not lead to price level changes without an increase or decrease in bank deposits. ‘In short, changes in the stock of deposits were to Wicksell the one absolutely necessary and sufficient condition for price level movements.’23 This was later echoed by Milton Friedman. Only if the central bank accommodated supply-side shocks by changing the price of credit could there be any price level changes. This was to lead to a hundred years of futile debate about what caused inflation: did the supply shocks cause money to expand, or did monetary expansion cause the supply shocks?

Why did Wicksell need the QTM? The quick answer is, for therapeutic purposes. He wanted the central bank to be able to offset fluctuations in the economy, and the only way it could influence the market rate was through the bank rate. Since the gold standard could not guarantee the appropriate bank-rate policy it should be replaced by an international paper standard, controlled by a committee of central banks.24

Two developments started to make the QTM operational for short-run stabilization purposes. The first was the development of the index number method of measuring the value of money. Secondly, by 1900 the gold standard was on the way to becoming a ‘managed’ standard, as central banks started to use changes in bank rate, variations in reserve requirements, open-market operations and central bank co-operation to offset gold flows.25 It was increasingly recognized that commercial banks could manufacture money by creating bank deposits. But as long as the central bank had the means of regulating the rate of money creation by the commercial banks, the existence of credit money seemed to pose no danger to its ability to control prices.

The heroic faith in the QTM as a short-run stabilization policy instrument, even though the QTM was palpably untrue in the shortrun, is explained by the urgency of its therapeutic ambitions. Even economists such as England’s Dennis Robertson and the Austrian Joseph Schumpeter, for whom the business cycle was caused by ‘real’ shocks like technical innovations, thought that intelligent monetary policy could prevent the rocking tendency from becoming too violent. But as Eprime Eshag wrote, the QTM was ‘somewhat wanting and to a large extent irrelevant as an instrument of analysis of shortrun unemployment and production problems which became the primary concern of the economists during and after the [Great Depression]’.26

Fisher built up his equation as follows:27

MV = ΣpQ

On the left, we have M for the money supply and V for the velocity of circulation. On the right, we have a summation of all the goods sold in an economy over a given period multiplied by their price. That is, we have:

MV = p1Q1 + p2Q2 + p3Q3 + . . . + pnQn

Here, Q1 and p1 might stand for the number of bottles of milk sold and their price, Q2 and p2 for the number and price of textbooks, and so on.

Fisher defines the Qs as ‘goods’ very broadly, to include ‘wealth, property, and benefits’.28 What counts as a ‘good’ is non-trivial, and can severely impact the usefulness of the equation of exchange and the validity of the QTM: this will cause trouble when we come to Milton Friedman and the 2008 crisis.29

We can then simplify things by giving P as a weighted average of all prices, and T as the sum of all the Qs, yielding:

MV = PT

Finally, Fisher distinguished between two kinds of currency. First, there is money proper (e.g. bank notes), and secondly, there are bank deposits. We can distinguish then between M (money proper) and M’ (bank deposits) and their respective velocities, giving us the final version of his equation:30

MV + M’V’ = PT