‘Taxes which are levied on a country for the purpose of supporting war, or for the ordinary expenses of the State, and which are chiefly devoted to the support of unproductive labourers, are taken from the productive industry of the country; and every saving which can be made from such expenses will be generally added to the income, if not to the capital of the contributors.’

David Ricardo, 18171

‘Institutions that initially existed to serve the state by financing war also fostered the development of the economy as a whole . . . In the beginning was war.’

Niall Ferguson, 20012

The second unsettled issue in macroeconomic policy concerns the economic role of the state. What part does the state play in creating wealth? Although this question was discussed in Han Dynasty China (81 bc) and by the fourteenth-century Arab scholar Ibn Khaldûn,3 it was not asked in Europe before modern times, partly because there was no state in the modern sense, partly because the growth of earthly wealth was not considered a justified (or feasible) object of human striving. The economy simply had to be kept productive enough to reproduce the social order. It was only from the sixteenth century onwards, with the voyages of discovery, the establishment of national states, the breakdown of the feudal economic system, and the emancipation of thought from religious doctrine that it became possible to envisage a future very different from, and better than, the past. The idea that wealth might deliberately be made to grow led a new school of political economists to question the economic practices by which humans had hitherto lived.

Their historical reflections led them to conclude that previous institutions had been severely dysfunctional from the point of view of wealth creation. In the past there had been great accumulations of wealth, but these had never led to self-sustaining growth. Rather, history disclosed a cyclical, not a progressive pattern: wealth expanded for a time and then contracted. Why was this? The political economists found the answer in the fact that the monarchs, soldiers and priests who made up ‘the state’ in traditional societies had appropriated, and then squandered, the wealth created by producers in wars, conspicuous display and great building projects to the glory of God and themselves. Even the richest states of old had been ruined by the extravagance and myopia of their ruling classes. Pre-modern rulers had invested too much in God, not enough in Mammon. Political economy set itself the task of providing the intellectual tools for breaking the mould.

Adam Smith contended that the growth of wealth depended on the spread of commerce (division of labour) and the accumulation of stock (investment). This was a distillation of post-medieval economic speculation, as was the view that a strong central state was needed to break down local barriers to trade and create a unified domestic market. However, two views emerged about the role of the state in economic development.

First in the field were the mercantilists, who gave the state a continuing role in trade promotion and accumulation. The mercantilists believed that state activity and spending could galvanize the growth of national wealth. War was an investment decision by the state: the state needed sufficient revenue to conquer foreign markets. Mainstream political economy, following the lead of Smith and Ricardo, rejected this programme. The state’s two essential economic tasks were to remove barriers to trade and to secure private property rights. It should be granted power and revenue proportional to these tasks, but no more. Central to this view was that trade sprang up spontaneously if obstacles were not placed in its way. This was as true of international as of domestic trade. From this point of view, resources devoted to wars of conquest were not an investment, but unproductive consumption. As Adam Smith put it in 1755: ‘Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.’4 Put simply, the state should get out of the way of private production for market. As the French merchants put it to the mercantilist minister Colbert, ‘laissez-nous faire’ – ‘leave it to us’. The mercantilist and laissez-faire views have fought it out ever since the birth of economics.

The Keynesian revolution of the twentieth century cut across this divide between mercantilism and laissez-faire by introducing an argument about state investment absent from both camps: the inability of a market system to maintain continuous full employment. Whereas all the disputes of pre-Keynesian economics were, at heart, about how most efficiently to create wealth from given resources, Keynes argued that, in normal circumstances, the limitation of effective demand prevented the full utilization of potential resources. The state should be allowed money not just to fight wars, but to bring into play additional resources.

In introducing an investment role for the state, Keynes also introduced a new division in economics, between macroeconomics and microeconomics. The essential claim of macroeconomics is that the study of the individual parts of the economy, i.e. microeconomics, even in combination, does not explain its total size. Put simply, the parts do not add up to the whole, because they are mutually dependent on each other.

We can classify these different positions, in roughly chronological sequence, by the simple criterion of how much the state should constitutionally be allowed to tax and spend:

1. The mercantilists saw the state as a wealth galvanizer, with the national debt and the accumulation of ‘treasure’ from export surpluses as its main instruments. The mercantilist outlook was general in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and has never disappeared, despite its repeated ‘refutation’ by later mainstream economics. Germany was the chief mercantilist nation in the nineteenth century; and Germany, China and Japan are examples of contemporary mercantilism.

2. Mainstream economists from Adam Smith onward believed that state spending, far from adding to ‘the national revenue’, subtracted from it. The loss should be minimized by keeping public spending as low as possible. Budgets should be balanced annually at the lowest possible level. The only trade policy should be free trade: the balance of trade was automatically selfcorrecting. Mainstream political economy dominated British fiscal policy in the Victorian age.

3. Keynesians believed that the state budget should be used to secure the full employment of potential resources. The Keynesian fiscal constitution ran roughly from 1945 until 1975.

4. The neo-Victorian fiscal constitution, running roughly from 1980 to 2008, marked a partial return to the Victorian fiscal ideal. The budget should normally be balanced at the lowest level of spending and taxes that politics allowed. An expanding national debt was the road to ruin. Insofar as economy-wide balancing was needed, this was to be done by monetary policy.

The economic collapse of 2008 threw both the theory and practice of fiscal policy into disarray. Government deficits spiralled all over the Western world and countries’ national debts crept up to 100 per cent of GDP or higher. Mostly this was an ad hoc response to the severity of the recession. But the slump severely damaged the consensus on fiscal policy, which had been taken for granted until recently, without producing any agreement on an alternative. On one side, there are the neo-Victorians, the fiscal hawks who want to get back to limited states and properly balanced budgets. On the other are the fiscal doves, who not only believe in the value of deficit spending in a slump, but who want fiscal rules flexible enough to dampen business cycles, secure full employment and boost economic growth.

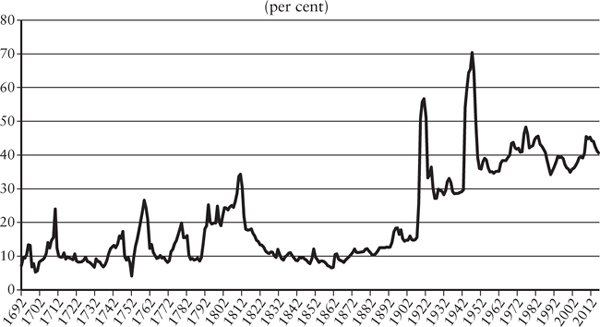

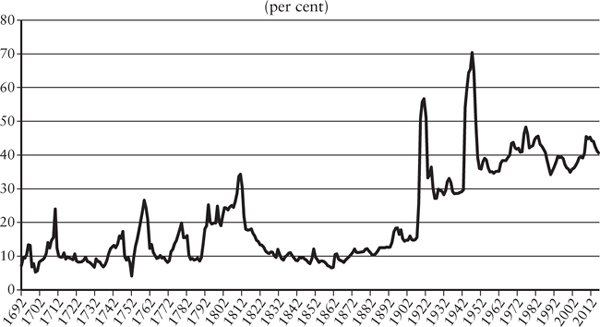

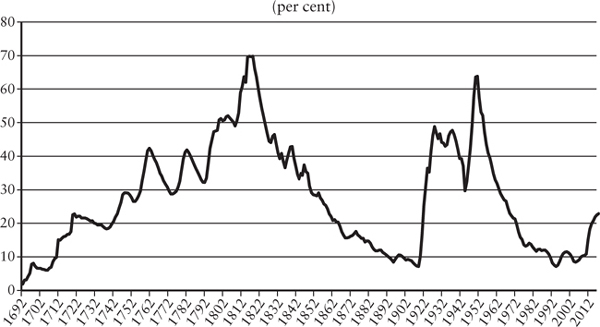

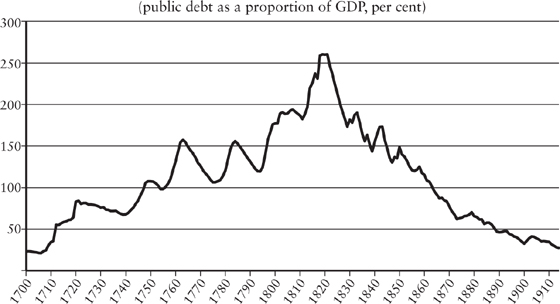

This chapter will explore how the debate between the mercantilists and the political economists played itself out in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But first, Figures 6 and 7 give a bird’s-eye view of Britain’s fiscal experience over the last three hundred years.

Figure 6. UK public spending as a proportion of GDP5

Figure 7. UK public debt as a proportion of GDP 6

Economies for most of history have been ‘state-led’ in the sense that the activities of rulers have determined whether they grew, stagnated or declined. But increased wealth (what we now call economic growth) only became the explicit object of state policy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Mercantilism was the first attempt to discover, by scientific reasoning, what it was that caused wealth to grow. In this endeavour, the mercantilists focused on the role of money and trade, and the state’s role in both. Foreign trade was regarded as the main impetus to wealth, but only if it produced a surplus of money for the nation. Hence mercantilism’s obsession with the ‘balance of trade’. Its leading features, according to Denis O’Brien, were ‘bullion and treasure as the key to wealth, regulation of foreign trade to produce a specie inflow, promotion of industry by inducing cheap raw material imports, export encouragement, [and] trade viewed as a zero-sum game’.7

Mercantilism was based on a fallacy, though quite a fruitful one: like pre-modern medicine, it had elements of truth and falsehood. The fallacy was the belief that exporting is better than importing, and that the object of economic policy should therefore be to secure a favourable balance of trade. This was the prevailing doctrine of most European states in this period. Of course, all countries cannot achieve a surplus simultaneously, so the pursuit of these policies involved continuing trade wars between the leading European powers.

Adam Smith accused the mercantilists of equating ‘wealth’ with ‘gold’. The more sophisticated of them never believed this. What they did believe was that accumulating gold was a means to increase a country’s share of the world’s wealth by fighting successful wars. This seems circular: a trade surplus was required for war; and war produced a trade surplus. But the mercantilists believed that for each state the benefits of having trading monopolies would outweigh the cost of acquiring them. In addition, some mercantilists believed that the influx of precious metals would reduce the rate of interest, and so stimulate domestic manufacturing.

The practical policy of mercantilism was to deprive rivals of trade opportunities. In a classic move, Britain passed a series of Navigation Acts, starting in 1651, and aimed mainly at the Dutch carrying trade; the Acts, among other prohibitions, restricted trade between Britain and its colonies to British-owned ships. ‘What we want is more of the trade [that] the Dutch now have,’ said the Duke of Albermarle. Another example was the Methuen Treaty of 1703, which allowed English textiles to be admitted into Portugal free of duty in return for a preferential tariff on the import of Portugese wine to England.

Mercantilism can thus best be seen as a policy of increasing the relative power and, by means of power, the wealth of individual states through manipulation of trading relations. Adam Smith’s claim to be the founder of scientific economics rests on his demonstration that trade need not be a zero-sum game, and that mercantilist policies, by restricting the size of the market, reduced the growth of wealth, and engendered the wars which justified them. David Ricardo put the case for free trade on a theoretically robust basis by proving arithmetically that, if countries were to specialize in producing and trading goods in which they were relatively more efficient, the real income of all the trading partners would be maximized – a logical demonstration that has stood the test of time, against all its critics, and provided a powerful normative argument for free trade policy. However, Ricardo’s arithmetic proof that specialization was best offered cold comfort to those domestic producers who were as efficient as their situation and endowments allowed them to be. Against his scientific demonstration we can cite the spirit of King James I’s proclamation: ‘If it be agreeable to the rule of nature to prefer our own people to strangers, then it is much more reasonable that the manufactures of other nations should be charged with impositions than that people of our own kingdom should not be set to work.’8 This argument for protectionism has always resonated, despite proof that free trade would be better.

There were some favourable consequences of mercantilist policies. They encouraged the centralization of state power, and this increased security of private property and fostered the unification of the internal market. They promoted manufacturing, exporting capacity and the growth of a merchant class (usually by grants of crown monopolies to chartered companies). They built up naval power. It is certainly a tenable view that the reduced cost of money engineered by the inflow of gold, together with the monopoly profits of commerce, helped finance Britain’s industrial revolution. The successful players in the mercantilist game (Britain was the most successful) did establish very powerful trading positions in Asia and North America, which survived the end of mercantilism; Britain’s imperial economic system, created in the mercantilist era, continued well into the twentieth century.

Niall Ferguson has provided a splendid picture of Britain as the model of the eighteenth-century fiscal warrior state.9 Constitutional limitations robbed the British state of its arbitrary character, but, paradoxically, its enhanced legitimacy made it a more effective agent of national purpose than the absolute monarchies of the continent of Europe. Navies were also much cheaper to run than armies. You can use the same ships and sailors for either trading or military purposes, and it was through its merchant marine that Britain built up its overseas trading empire from the 1600s onwards. Countries striving to emulate Britain’s economic performance placed more emphasis on the state’s creative power than on the constitutional limitations prescribed by British liberal thinkers like John Locke, or the precepts of fiscal finance adumbrated by Adam Smith.

Britain’s fiscal constitution was based on the idea that wealth was generated through the competitive struggle of nations. The edge lay not with the states with the largest resources, but with the states that could most efficiently mobilize resources for their foreign policy goals. The constitutional character of the British monarchy gave it an enhanced revenue-raising power. Additionally important was the centralization of tax collection in a paid bureaucracy, instead of relying on tax farming – leasing out tax collection to private agents – and the sale of offices. This enabled the British government to raise 12.4 per cent of GNP in taxes in 1788, compared to France’s 6.8 per cent.10

As Ferguson tells it, the institutions for mobilizing resources were Parliament, the tax bureaucracy, the national debt and the central bank. The superior development of this financial ‘square of power’ in eighteenth-century Britain gave it not only a decisive military advantage over its main rival, France, but also a faster rate of economic growth.11

However, the principal fiscal weapon for the struggle was the national debt, and the main issue for fiscal policy, then as later, was the sustainability of this national debt. ‘In a fiscal state, a steady and secure flow of tax revenues forms the basis for large-scale borrowing without the threat of default and hence the need for the state to pay high interest rates to obtain funds.’12 Britain ‘out-taxed, out-borrowed, and out-gunned’ France in the Napoleonic wars.13 Ferguson traces the origins of modern debt finance to a series of financial innovations in England, starting with the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 (France only got its central bank in 1800) and the adoption of the gold standard in 1717, and culminating, in 1751, in the birth of ‘Consols’ – the consolidated debt of the British government in the form of liquid, but perpetual, bonds redeemable at par.14 The effect of these innovations was to increase the size of the sustainable public debt. Undertaken for warlike motives, the measures not only enabled Britain to beat France in a long struggle for dominance, culminating in the Napoleonic wars, but they also stimulated the growth of commerce. The key point here is that the proliferation of tradable public debt instruments ‘effectively created the private market for private sector bonds and shares’ by spreading risk.15 Moreover, ‘the emergence of the bondholders as an influential lobby within parliament reduced the risk of default by the British state and thereby increased the state’s capacity to borrow cheaply’.16

In short, Hanoverian England was a brilliant war machine and commercial engine. The wealth accumulated through commerce enabled it to become the ‘first industrial nation’. Succeeding generations paid off its huge public debt out of the proceeds of its economic growth. The mercantilist policy of Britain’s eighteenth-century Hanoverian monarchy, which laid the basis for the Pax Britannica, was abandoned by Britain itself, but became the model for successful state performance of all those countries trying to ‘catch up’ with Britain.

The late eighteenth century saw a turning away from the warlike state. Adam Smith may have written that ‘defence . . . is of much more importance than opulence’, but he saw the mercantile system of his time, and its wars, as having ‘not been very favourable . . . to the annual produce’.17 Like his contemporaries, the French ‘physiocrats’, he believed that the source of wealth was ‘produce’ – though he extended the meaning of this term to include manufacture as well as agriculture. Against the protectionism of mercantilism, Smith roundly asserted that consumption was ‘the sole end and purpose of all production’.18 From this point of view, restricting domestic consumption in order to achieve an export surplus was irrational. The national debt incurred to pay for the mercantilist wars restricted the growth of wealth, and therefore consumption.

An important part of Smith’s case for the wastefulness of state spending rested on his argument that trade, left free, conferred benefits on both trading partners. One did not need wars and monopolies to have a great commerce. It would come about organically under conditions of ‘natural liberty’. Book IV of Smith’s Wealth of Nations is devoted to an attack on the mercantilist system. Mercantilist wars were fought for the benefit of the sovereign and vested interests, at the expense of the consumer.

The analytic basis of the doctrine of state frugality is straightforward. According to Smith, wealth is increased by the accumulation of capital through saving and investment.19 Taxation diverts income from private accumulation to state consumption, and therefore subtracts from wealth creation. The state is, by definition, unproductive. Smith and his followers saw strengthening Parliament’s control of revenue at the expense of the monarchy’s as the way to reduce state consumption.

Classical economists aimed to limit, not abolish the state. According to Smith, the system of ‘natural liberty’ leaves the state four duties: defence of the country; administration of justice; responsibility for education; and

erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain, because the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals, though it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society.20

In modern parlance, these works and institutions are called ‘public goods’: goods which, for one reason or another, cannot be supplied by the market, and for Smith included those which ‘facilitate the commerce of any country, such as good roads, bridges, navigable canals, habours, etc.’, as well as a system of national education to repair the ravages to human intelligence wrought by the division of labour.21 For these duties, but only these, the state had to be provided with revenue. Having only a modest list of duties, the state’s revenue should also be modest. ‘Be quiet’ was Bentham’s famous prescription for government: leave economic growth to the natural desire for improvement.

Smith ignored mercantilist concern with money and employment. Money was simply a lubricant. The economists who followed Smith believed that in conditions of natural liberty all savings would be invested, resources fully used.

Taxation does not appear in the index of The Wealth of Nations, but there is a large section on the national debt, the growth of which in the 1700s Smith regarded as the main impediment to increased prosperity. ‘Like an improvident spendthrift, whose pressing occasions will not allow him to wait for the regular payment of his revenue, the state is in the constant practice of borrowing of its own factors and agents, and paying interest for the use of its own money.’22 Issuing debt was a way of extracting money from the citizen by stealth. ‘There is no art which one government sooner learns of another than that of draining money from the pockets of the people.’23

Through borrowing, the sovereign was enabled to fight expensive and unnecessary wars. Smith had little faith that a sinking fund for repayment of debt would solve the problem of ‘perpetual funding’, since the reduction of public debt in peace had never been proportional to its expansion in war.24 In the past, liberation of the public revenue from debt burdens had been brought about by open default or ‘a pretended payment’ (inflation).25 But Smith denounced this as a ‘treacherous fraud’, which destroyed the state’s creditworthiness.26

The only possible advantage of borrowing to finance wars was that it might make more saving possible than if the whole cost of wars was raised by taxation alone.27 Indeed, Smith attributed the prosperity which, contrary to his polemic, had accompanied the big expansion of the national debt in the eighteenth century, to the fact that state borrowing had not impeded the growth of saving. By their inherent frugality, the British had been able to repair ‘all the breaches which the waste and extravagance of government had made in the general capital of society’.28

The only honest way to pay off the national debt was by increasing taxation or cutting spending. Smith thought the colonies should be taxed to pay for their defence. But if they couldn’t be made to pay, Britain should rid herself of the delusion of empire ‘and endeavour to accommodate her future views and designs to the real mediocrity of her circumstances’.29

Smith’s argument, that state spending ‘crowded out’ productive private spending, was reinforced by Ricardo. Ricardo regarded all state expenditure as inherently wasteful. Taxes and public loans equally destroy capital. But, unlike Smith, Ricardo thought that raising loans to pay for state expenses ‘tends to make us less thrifty’, by deceiving us that we only have to save to pay the interest on the loan, rather than our share of its full tax equivalent.30 This is interesting, because while Ricardo’s analysis led him to believe that borrowing was simply deferred taxation, he did not believe that the taxpayer necessarily understood it to be so.31

Countries, said Ricardo, should use periods of peace to pay off the national debt as quickly as possible, and ‘no temptation of relief, no desire to escape from present, and I hope temporary, distresses, should induce us to relax in our attention that great object’.32 So a proper sinking fund should be set up. Writing after the Napoleonic wars had left Britain a national debt of 260 per cent of national income, Ricardo asserted that if, by the time of the next war, the national debt had not been considerably reduced, either that war must be paid for by taxation, or the British state would be bankrupted. In the period covered by this book we shall encounter four big spikes in the national debt: post-1815, post-1918, post-1945 and post 2008–9; the first three were caused by war, the last by government’s response to economic collapse. Each ‘excess’ led to the restoration of ‘virtue’ in the form of fiscal austerity.

The repudiation of mercantilism outlined above reflects the turn of economics from a monetary to a ‘real’ analysis. The mercantilists (and most other ‘pre-scientific’ economic thinkers) stressed the role of money, credit and public finance in fertilizing economic activity, whereas in the ‘real’ analysis of Smith and Ricardo the growth engines are thrift and productivity, with money as a mere ‘veil’ which hid from people their true circumstances, and taxation and public borrowing subtractions from both.33 As Mill wrote in 1844, no one any longer argued for the ‘utility of a large government expenditure, for the purpose of encouraging industry’.34 Earlier, David Hume had pointed out that the mercantilist concern with ensuring, through an export surplus, a sufficiency of the precious metals, was a delusion (see above, p. 37). The economic task was to ensure the most efficient allocation of ‘real’ resources. This was best left to the market.

In the rejection of mercantilism by the classical economists it is not clear whether ideas or circumstances were in the driving seat. George Stigler believed it was ‘the absence of major wars’ in the nineteenth century which caused the state’s role to recede and the ‘reign of liberty’ to expand.35 However, it is possible that the change in economists’ views about how to obtain wealth caused the incidence of war to decline. It may also be that peace and war, progress and decay, are subject to long cycles, with economic theory adapting to each phase of the cycle.

Put into practice from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the classical economists’ view of the state’s role dominated British fiscal policy until the First World War, and it limped on afterwards into the 1930s. The views of Smith, Ricardo and Mill, though not cited directly, were part of the mental equipment of the frugal Victorian Treasury. Deficit finance was shunned; budgets were to be annually balanced. Central government was to be kept small in relation to the economy. ‘A Chancellor was judged not only on his ability to balance his budget but also to reduce the National Debt.’36 Maintaining a regular sinking fund for debt redemption was considered part of ‘balancing the budget’. Surpluses were to be used only to reduce the national debt and not spent the following year. Free trade triumphed after 1846, when Parliament repealed the Corn Laws protecting British agriculture.

Ricardo would have been pleased with the progress in reducing the national debt shown in Figure 8; by the outbreak of the First World War, the debt–GDP ratio had fallen to a fifth of its peak in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars. In a recent analysis of debt reduction between 1831 and 1913, Nicholas Crafts argues that much of this success can be attributed to a strong commitment to balancing the budget. The British government ran persistent primary budget surpluses over the course of almost a century, with only six instances of a deficit higher than 1 per cent of GDP. There was no inflation, and the government would not have been able to rely on buoyant growth alone, since real interest rates on the debt in this period were consistently higher than real growth rates.38

Figure 8. The rise and fall of UK war debt37

A crucial innovation was income tax, first levied in 1814, and renewed by Peel in 1842. By 1911–14, this had become the principal source of government revenue. Income tax had the double benefit of giving the British state a secure revenue base, and aligning voters’ interests with cheap government, since only direct taxpayers had the vote. Legitimacy of the taxation system was enhanced by strengthening Treasury control and giving responsibility for assessing tax liability to the Inland Revenue, independent of government. ‘Fiscal probity’, under Gladstone, ‘became the new morality.’39

Public spending as a share of GDP fell from 1830 to 1870, then remained flat, before the Boer wars and increased military spending in the run-up to the First World War caused a rise. In 1900, the British government spent 14 per cent of GNP, the proportion having been under 10 per cent for most of the nineteenth century. Spending on social services came to 2.6% of GNP; economic services (agriculture, forestry, fishing, industry, transport and employment) took 1.9% of GNP; defence, law and order 7.4%; interest on the national debt 1%; with the rest spent on administration, overseas services and environmental services (the provision of basic services such as roads, lighting and water).40 The government owned no industries except the post office and a few ordnance factories; income tax was tiny, and most people were below the direct tax threshold, though there were indirect taxes (‘excise duties’) on working-class ‘sins’ like drink and gambling. Municipal utilities such as gas and water were financed by loans from central government to local authorities. But most of what we now think of as welfare was still provided by voluntary insurance and private philanthropy. The state was thus too small to have much direct influence on aggregate demand, either through discretionary spending or built-in stabilizers. Not that it was expected to.41

Though limited borrowing was permitted in times of war, this exception was not to be taken lightly; as far as possible, war was still to be financed out of current tax receipts. When this was not possible, current budget deficits were to be financed by long-term debt, repaid as soon as peacetime allowed current budget surpluses again.42 However, with the British Navy ruling the waves, and free trade replacing protectionism, peace came to be regarded as the norm.

The Victorian minimal-expenditure constitution was challenged by the Liberal government’s social reforms in the 1900s, as well as by the need to increase defence spending to meet the German threat. Social reform was partly driven by a desire to ensure a workforce that could compete with the United States and Germany, partly by the extension of the suffrage. Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909 proposed increasing the standard rate of income tax to 1s in the pound (a rate of 5 per cent) for incomes between £2,000 and £3,000, and to 1s 2d (5.8 per cent) for incomes over £3,000, as well as introducing an additional super tax of 6d (2.5 per cent) on the amount by which incomes over £5,000 exceeded £3,000. He also proposed raising death duties (inheritance tax) and introducing a 20 per cent tax on any increase in land value when that land changed hands – all to a torrent of execration from the wealthy. These taxes were partly to pay for an enlarged social budget, which now included grants for education, old-age pensions and ‘social’ insurance against sickness and unemployment.43 Yet diverging from the expenditure-minimization tradition did not mean abandoning the balanced-budget rule: ‘the desire to obtain a budget surplus to reduce the Debt remained as strong as ever’.44 And, despite the emergence of business cycles, there was no hint yet of a state duty to maintain a high level of employment.

Historians have dubbed Britain’s fiscal constitution ‘precocious’ or ‘exceptional’.45 Having fought the wars of the eighteenth century to become ‘top dog’, Britain had no need for an energetic state, and preached laissez-faire and free trade. Latecomers to the feast learned more from Britain’s eighteenth-century practice than from its nineteenth-century precepts. Catch-up economics was explicitly national.

The most important theoretical criticism of the Smithian system came from the German economist Friedrich List, who, in turn, had picked up many of his ideas from Alexander Hamilton, theoretician of American protectionism. Ricardo’s doctrine of comparative advantage, a sophisticated argument for free trade, was a theory of static equilibrium, which left the first successful trader in any free trade world with the most valuable advantages. But, as List pointed out, the ‘power of creating wealth is infinitely more important than wealth itself’.46 And the power of creating wealth belonged to power proper, because – as history had amply shown – ‘a nation, by means of power, is enabled not only to open up new productive sources, but to maintain itself in possession of former and recently acquired wealth’.47

What mattered to List (and in this he spoke for most German economists) was not the riches of individuals, but the nation’s well-being. List criticized Adam Smith’s school of thought for (i) its ‘boundless cosmopolitanism’, which ignored national interests; (ii) its ‘dead materialism’, which ignored mental and moral aims; and (iii) its ‘disorganising particularism and individualism’, which ignored social cohesion.48 The German Historical School of economists redefined mercantilism as ‘nation-building’. They introduced the important, but now neglected, idea that the validity of economic doctrines depends on circumstances. What might be good for a nation at one time might be quite unsuitable for it at another. Free trade, List remarked scornfully, was the doctrine of a country which, having ‘attained the summit of greatness . . . kicks away the ladder by which [it] has climbed up . . . In this lies the secret of the cosmopolitical doctrines of Adam Smith.’49 So List added to the state’s four duties, listed by Smith, the development of the ‘productive forces’.

Economics (just about) recognizes List’s ‘infant industry’ argument as an exception to the general case for free trade. It fails to recognize that he founded a general theory of economic development, of which free trade is a special case.

German policymakers took List’s teaching to heart. The financial, commercial and industrial machine that Britain had developed haphazardly over two hundred years, Germany built deliberately in half a century. First came the Zollverein, or customs union, of the separate German states between 1834 and 1866, linked together by a bondfinanced railway system, and capped by the establishment of the German Empire in 1873. In 1879, following the Great Depression (see above, p. 51), Bismarck liquidated Germany’s free trade moment by imposing tariffs on foreign grain and industrial products, and starting compulsory social insurance for health, accidents and old age. Under cover of Protection, German industry surged ahead on all fronts: heavy industry – machine-building, electrical engineering and construction – followed by chemical engineering, precision mechanics and optics. The giant Kiel Canal, linking the North Sea to the Baltic, was built with funds from the naval budget between 1887 and 1895. Before the end of the century Germany had overtaken Britain in industrial production, and ‘Made in Germany’ rivalled ‘Made in Britain’ as the protected home market became the springboard for Germany’s assault on world markets. With its deliberate attention to product innovation and vocational training (theoretical and practical), its network of research institutes, its corporatist business structure linking big business and investment banks, and its social insurance schemes, Germany’s organized capitalism bore little resemblance to Manchester liberalism. As a contemporary French journalist explained: ‘The Germans . . . looked ahead in a broad-minded, farsighted manner.’50

In the United States, too, the needs of catch-up subverted the aggressive business ideology of laissez-faire. Tariffs on foreign goods were seen both as a means of economic growth and as providing the government with revenue in a federal system.51 Tariffs shielded industry throughout the nineteenth century; the state funded big infrastructure projects, such as the Erie Canal linking the Great Lakes to the Hudson river. Because of the ‘wild west’ character of American business expansion, the Federal government were also pioneers in the legal regulation of business life. By the end of the 1800s, the United States, too, was forging ahead of Britain industrially. Its conversion to free trade and deregulation came only in the 1940s, when it had replaced Britain as ‘top dog’.

Most developing countries in the twentieth century learned their economics from Hamilton and List rather than from Smith and Ricardo. That is to say, they set about, under state direction, shaping their trading advantages, rather than passively accepting those supposedly bequeathed by the first-starters. They were unashamedly mercantilist, believing in free exports but controlled imports. And, in a reprise of the nineteenth century, they came under increasing pressure from the already rich countries to abandon their policies of import substitution.52

Of most concern to us here is the attitude of different countries to the national debt. For most countries, public borrowing was a necessity. Lacking efficient tax systems, they had to borrow to finance even routine activities, let alone wars, relying on the yields of customs duties and other state monopolies to pay back their creditors. The survival of tariffs in the nineteenth century is partly explained by the state’s need for revenue.

The combination of huge public debts left over from the Napoleonic wars and the lack of reliable sources of tax revenue gave private moneylenders like the Rothschilds their dominant position in the middle years of the nineteenth century.53 The Rothschilds created the international bond market. Nathan Rothschild’s loan to Prussia in 1818 set the pattern for future loans. It was a fixed-interest sterling loan, with investors being paid in London, not Berlin; this removed both the risk of loss on the exchange rate and the inconvenience of collecting interest from abroad. Nathan Rothschild insisted that the ‘good faith’ of the borrowing government had to be underpinned by a ceiling on state debt and a mortgage on the royal estates – the first time that such conditions had explicitly featured in contracts between money-lenders and sovereigns, anticipating the modern concern with the problem of debt sustainability.54 As Nathan Rothschild explained to the Prussian state Chancellor: ‘Without some security of this description any attempt to raise a considerable sum in England for a foreign Power would be hopeless.’55 In Niall Ferguson’s words, ‘If investors bid up the price of a government’s stock, that government could feel secure. If they dumped its stock, that government was quite possibly living on borrowed time as well as money.’56 This was the classical creditor position.

The Rothschilds certainly talked as if they had a vested interest in peace. They reiterated that ‘it is the principle of our house not to lend money for war’.57 Yet, a glance at their balance sheet shows that they made most of their money by financing preparations for war and the international transfers that tended to follow. The ‘golden age’ of the Rothschilds, from 1852 to 1874, spanned the Crimean War and the four wars of Italian and German unification. The reason is clear: the wars of the 1850s and 1860s were fought by states that were, by and large, strapped for cash. Wars and war scares might depress the prices of existing bonds, but they greatly increased the yield – and hence attractiveness to investors – of new debt. On 30 April 1859, Rothschild’s London house cabled its Paris partner: ‘Hostilities have commenced. Austria wants a loan of 200,000,000 florins.’ With the rise of competitor banks, the Rothschilds knew that they had no ‘veto on bellicosity’. If they failed to underwrite loans to states, others would. The fatal weakness of banking pacifism was that profits came before peace.

The Rothschilds were also drawn into ‘lending money for war’ by their involvement in railway bond issues. The railway lines that linked Austria to Germany, Italy, Hungary and the Balkans, paid for by the Vienna Rothschilds and their subsidiary, the Creditanstalt, were largely built for military purposes. In the ‘war of the railways’ in the 1850s, the multinational resources of the Rothschilds triumphed over the resources of their Parisian rival, the Péreire brothers. But their railways were thereafter hostage to state policy.

Reliance on international bond markets imposed a discipline on the fiscal and exchange-rate policies of states, just as it does today. Although the merchant banks were rivals, they could agree on what made a particular state creditworthy. It was their business to do so, for had they not been able to secure their loans, no one would have invested in them. So the bond markets played a crucial role in promoting ‘sound finance’. The bankers were equally ardent advocates of ‘sound money’. By the end of the nineteenth century, foreign state loans were usually made conditional on their recipients joining the gold standard. With Britain’s example before them, the bankers understood that constitutional monarchies were more likely than absolute ones to repay debt, and tried to make constitutional reform a condition of loans – for example, in the Rothschild loan to Austria in 1859. But the spread of constitutional government had a paradoxical consequence. By making states more efficient in collecting taxes, it weakened their need for international bankers.

With the improvement of state revenues, the development of deposit and joint-stock banking, and the growth of domestic capital markets, there was less demand for the financial services supplied by the ‘Jews of Kings’. In the last third of the nineteenth century, the bankers’ power weakened as nationalism came to the fore and as governments’ fiscal positions strengthened. The introduction of income tax in Prussia between 1891 and 1893 made it possible for Germany to adopt Britain’s balanced-budget rule.58 But governments in Latin America continued to rely on the services of international bond markets to finance their needs until well into the twentieth century, their frequent defaults not deterring the optimism of investors for long.

State borrowing was not just a matter of necessity; necessity alerted people to its advantages. Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Secretary of the Treasury, wrote: ‘a national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing, an “invigorating principle”’.59 His rationale was that public debt enlarged the pool of private credit, thus enhancing investment. This argument faded with the deepening of private credit markets. But another argument for public debt survived. Throughout the 1800s Prussia made public investments in technical education, roads, key industries, railways and an overseas trading corporation, as part of its policy of ‘catching up’ Britain. In this, the state worked closely with industrialists and was able to staunch the emigration of young Germans to America. As W. O. Henderson concludes in his assessment of German economic development, Bismarck ‘realised the influence which the central Federal governments could exercise over industrial developments through their control over the public sector of the economy’.60

The difference between mercantilists and classical liberal economists was one of means, not ends. Both wanted to increase national wealth through state action, but whereas mercantilists favoured direct intervention through investment and trade policy, liberals sought to confine the state to creating the background conditions for a free market. The latter’s self-presentation as ‘anti-state’ was a deception, springing partly from lack of historical perspective and partly from ideology: clearly a market order looks more attractive if presented as the result of a spontaneous growth rather than as an artefact of state power. The deception persists to this day, with the neo-liberals loudly proclaiming their faith in the free market, even though in reality it would not exist for a day without continued state support.

The history of fiscal theory shows that, far from being the scientific paragon it claims to be, it is highly ideological, reflecting economic circumstances, historical mythology and class forces, with the enabling concept of public goods waxing and waning with circumstances and the size of the franchise.