‘[Central banks should] employ all their resources to prevent a movement of [the price level] by more than a certain percentage in either direction . . . just as before the war they employed all their resources to prevent a movement in the price of gold.’

J. M. Keynes, 19231

‘. . . very little additional employment and no permanent employment can in fact and as a general rule be created by State borrowing and State expenditure.’

Winston Churchill, 19282

‘In the case of any new proposal all one can do is to show there are some theoretical reasons for thinking it might be effective, and then . . . to make the experiment and see how successfully it is carried out.’

J. M. Keynes, 19243

Before the First World War, monetary reformers such as Fisher and Wicksell had urged that central banks should deliberately use monetary policy to stabilize the price level, and not just be automatic transmitters of international gold flows. The ‘management’ of the gold standard had started, but it had not got very far. The democratic innovations of the war, which involved extending suffrage and trade union control over wages, increased the urgency of the task. With industrial economies losing their ‘elasticity’, a more elastic currency was required.

Once it came to be accepted as prudent, for social reasons, to use monetary policy to mitigate dislocating economic fluctuations, all the unsettled questions in monetary theory were reopened. Was the money supply exogenous or endogenous? What was the transmission mechanism from money to prices? Was the task of the central bank to control currency or credit? Was it possible to combine price stability with exchange-rate stability? The context of these discussions was the radical volatility of prices, very different from the muted modulations of the previous century: post-war hyperinflation in some countries being followed by price collapses.

John Maynard Keynes and Edwin Cannan debated the causes of the wartime and post-war inflations in a re-run of the Currency versus Banking School debates of the early nineteenth century. Cannan, a professor of economics at the LSE, denied that banks create money. To him they were simply cloakroom attendants, who issued tickets for money deposited with them. It was the central bank that produced the ‘extra’ money. Thus the problem of stopping inflation boiled down to limiting the issue of central bank notes. Cannan wrote as much in his book The Paper Pound, first published in 1919: ‘Burn your paper money, and go on burning it till it will buy as much gold as it used to do!’4

Keynes restated the credit theory. Banks created deposits in response to the ‘needs of trade’. Money could not, therefore, be in ‘over-supply’. Old-fashioned theorists like Cannan claimed that credit expansion followed currency expansion. But, wrote Keynes, in a modern community with a developed banking system, expansion of notes was ‘generally the last phase of a lengthy process of credit creation’. To reverse the credit expansion after it had occurred by preventing the quantity of notes from increasing would only bankrupt the business world – ‘a course often followed in former days when Professor Cannan’s doctrine still held the field’. Control of credit, not control of currency, was the key to price – and, by extension, economic – stability.5

How was credit to be controlled? In the Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), Keynes wrote down the following equation:6

n = p(k + rk’)

where n is currency notes, p is the cost of living index, k is the amount of real ‘purchasing power’7 people keep as cash (outside banks), k’ the amount they keep in bank deposits, and r the fraction of these deposits in bank reserves. In equilibrium, k and k’ (velocity) are stable, but when the ‘mood of business’ is changing, it will be the task of the central bank to deliberately vary n and r (the banks’ ratio of reserves to liabilities) so as to counterbalance the movements of k and k’. In short, the Bank of England needed to vary the stock of high-powered money to offset changes in the supply of, and demand for, credit. Managing expectation plays the key role in Keynes’s scheme of monetary therapy. The central bank must create a confident expectation that the price level will not move more than a certain percentage either way from the price of a standard composite commodity.8 The message was clear: he who would control money has to control expectations about future prices. This, as we shall see, was the rationale for the inflation targeting adopted in the 1990s.

Like his predecessors, Fisher and Wicksell, Keynes encountered the problem of the gold standard. Bank Rate could be used to stabilize either domestic prices or the exchange rate. It could not do both. Not surprisingly, he condemned the gold standard as a ‘barbarous relic’, thwarting the beneficent purposes of ‘scientific’ monetary policy.9

In the textbook account, a country’s money stock bore a fixed proportion to its banking system’s gold reserves, and was inflated or deflated as gold flowed in and out of the country. The problem of keeping domestic prices fairly stable had, to some extent, been finessed by the flexibility of the central bank responses to gold movements, but mostly by the hegemonic role of sterling in the international payments system. After the war, however, the system was rendered unstable by ‘British inability and United States unwillingness’ to assume these responsibilities.10

Because of the wartime inflation, the British government suspended convertibility in 1919, for the first time since 1797. Prices skyrocketed; the exchange rate plummeted. Bank rate was put up to 7 per cent in 1920 to check the inflationary boom, a reasonable step in the circumstances, but it was then held at this now punitive rate in the subsequent year and a half of collapsing prices, output and employment in order to prepare for a resumption of convertibility at the old sterling–dollar exchange rate. This was the Cunliffe adjustment mechanism (see pp. 54–5) being applied not just to liquidate the inflation, but to restore the previous gold value of the pound, in an echo of Locke and Ricardo.

In the spirit of the monetary reformer, Keynes attacked the aim of forcing up the value of sterling. It was to no avail. The aim of policymakers was to put the tried and tested anti-inflation anchor back in place as soon as possible. Germany went back on to gold in 1924, Britain in 1925, and France and Italy in 1927.

Keynes’s Treatise on Money (1930) explicitly showed the influence of Wicksell.11 The business cycle, or what Keynes called the credit cycle, was caused by the deviation of the market rate of interest from the natural rate of interest, or, equivalently, of saving from investment. Keynes now proposed a ‘dual method’ of controlling the credit cycle: old-fashioned variation in bank rate and the newer technique of open-market operations. Bank rate set the short-term rate; but direct action on the term structure of rates was needed to enforce the official rate in the market. By buying and selling securities (open-market operations) the central bank could vary the amount of cash reserves held by member banks, which they used as the base of a superstructure of credit. Keynes wrote in 1931:

A central bank, which is free to govern the volume of cash and reserve money in its monetary system by the joint use of bank rate policy and open-market operations, is . . . in a position to control not merely the volume of credit but the rate of investment, the level of prices and in the long run the level of incomes, provided that the objectives it sets before it are compatible with its legal obligations, such as those relating to maintenance of gold convertibility or to the parity of the foreign exchanges.12

Keynes’s espousal of the credit theory of money was, as can be seen, limited. He needed a cash base – exogenous money – for open-market operations to be feasible. In a modern monetary system, paper cash is the substitute for gold cash and the central bank does the job of the gold standard, only ‘scientifically’. In short, Keynes did not entirely jettison the Quantity Theory of Money.

Unfortunately, Britain was in no position to try out the ideas of the monetary reformers. The mistaken policy of relinking the pound to gold at an overvalued exchange rate had resulted in a low employment trap. The worst of all possible worlds, Keynes wrote, is one where

spontaneous changes in earnings tend upwards, but monetary changes, due to the relative shortage of gold, tend downwards, so that . . . we have chronic necessity for induced changes [in wage levels] sufficient not only to counteract the spontaneous changes but to reverse them. Yet it is possible that this is the sort of system which we have today.13

Between 1925 and 1929, Keynes wrestled with ways of relieving unemployment within the constraints of the gold standard: curbing capital exports, public investment schemes, co-ordinated money wage reductions. But the scope for action within the golden cage was limited.

Because it did not have to worry about the balance of payments, the United States was the only country in a position to try out the ideas of the monetary reformers. Its current account surpluses produced a steady inflow of gold into the Treasury’s strong box, Fort Knox. By ‘sterilizing’, or hoarding, these inflows, the Federal Reserve System, established in 1913, could prevent them from raising domestic prices, and thus insulate the domestic value of the dollar from that of gold.

Influenced by Keynes, the Fed subscribed to what is known as the ‘Reserve Position Doctrine’. This held that the first effect of an increase in a central bank’s open-market investments will be to cause an increase in the reserves of the member banks. Hence, by injecting or withdrawing cash reserves the Fed would be able, by altering the reserve base of member banks, to cause them to lower or raise the interest rates they charged on loans. This, explained Paul Warburg in 1923, would enable the Fed to exert a ‘strong regulatory effect’ on the economic system.14

Maintaining stable prices at full employment between 1923 and 1928 by means of open-market operations (OMOs) was considered a triumphant vindication of the ‘scientific’ monetary policy pursued by the US Federal Reserve Board, and particularly its Governor, Benjamin Strong. However, a less noticed consequence of the sterilization of gold inflows was that it blocked David Hume’s price–specie–flow mechanism. The dollar became progressively undervalued, as did the French franc, which had stabilized the gold–franc exchange rate in 1927 at a large discount to the pound. These two gold ‘hoarders’, which, by 1929 had amassed 60 per cent of the world’s monetary gold stock, exerted a deflationary pressure on the rest of the gold standard world, only partly mitigated by US loans to Germany and Latin America and French loans to Eastern Europe.

Triumph turned to ashes when the Fed failed to prevent the collapse of the US economy in 1929. Following the Wall Street stock market crash of 23 October that year, US output, employment and the money supply plummeted. The world economy was soon reeling from the worst depression since the industrial revolution.

The causes of the crash of 1929 have been much disputed. Friedrich Hayek claimed that it was a result of excessive credit creation in the United States. In his account, the price stability of the mid-1920s, so much praised by the monetary reformers, was an indicator of inflation, not of equilibrium, since productivity gains would have naturally produced a falling price level. Rather than central bank policy, compelling banks to hold 100 per cent reserves against deposits was the only secure way to prevent an inflationary boom, bound to turn into bust. ‘Excessive credit creation’ became the standard ‘Austrian’ explanation of the 1929 collapse. It resurfaced to explain the crash in 2008. Keynes’s alternative view was that it was the Fed’s misguided raising of its discount rate, from 3.5 per cent to 5 per cent in January 1928, which led to the collapse of a healthy investment boom. It turned him permanently against the use of ‘dear money’ as a boom-control mechanism.15

‘Never waste a recession,’ Joseph Schumpeter is said to have said. On the Austrian analysis, recessions give a chance to re-allocate ‘malinvested’ productive factors to efficient uses. They should therefore be allowed to run unhindered until they have done their work. Economists whose common sense had not been completely destroyed by their theories rejected the drastic cure of destroying the existing economy in order to rebuild it in the correct proportions. Milton Friedman, heir of the monetary reformers of the 1920s, would later claim that the Fed could and should have prevented the slide into a ‘great’ depression by expanding its open-market operations – buying government bonds – to whatever extent was needed to offset the flight into cash. In practice, OMOs on a large scale started only in 1932.

In The Great Contraction (1965) Friedman and Schwartz write:

The drastic decline in the quantity of money during those years and the occurrence of a banking panic of unprecedented severity . . . did not reflect the absence of power on the part of the Federal Reserve System to prevent them. Throughout the contraction, the System had ample powers to cut short the tragic process of monetary deflation and banking collapse. Had it used those powers effectively in late 1930 or even in early or mid-1931, the excessive liquidity crises . . . could almost certainly have been prevented and the stock of money kept from declining or, indeed, increased to any desired extent. Such action would have eased the severity of the contraction and very likely would have brought it to an end at a much earlier date.16

Friedman and Schwartz blamed the monetary debacle on weak leadership by George Harrison, who had succeeded Benjamin Strong as President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Their conclusion had a powerful effect on those in charge of central banks in 2008, especially Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Fed in 2007–8. According to Tim Congdon: ‘The monetary interpretation of the Great Recession pivots on the proposition that the collapses in economic activity seen in the worst quarters of 2008 and 2009 were due to falls in – or at any rate sharp declines in the growth rate of – the quantity of money.’17

At the time, Keynes agreed with Friedman’s retrospective analysis. In 1930 he advocated ‘open-market operations à outrance’ – buying government securities to whatever extent necessary – to ‘saturate’ the desire of the public to hoard money.18 This presupposed that the central bank had the power to expand the quantity of money without limit. But the Bank of England had never shared the confidence of the monetary reformers that the Bank could control the volume of credit at will, as Keynes was soon to discover.

Friedman wrote that ‘[t]he quantity of money in the United States . . . fell not because there were no willing borrowers – not because the horse would not drink . . . [but] because the Federal Reserve System forced or permitted a sharp contraction in the monetary base’.19 Critics pointed out that the monetary base (currency held by the public plus the reserves of the banking system) increased by 10 per cent during the period when broad money, which includes loan deposits, fell by 33 per cent. So it may well have been a case of ‘an insufficient demand for loans – of the horse refusing to drink’.20

There is no secure way of settling this argument. Laidler believes that the Fed did not inject enough cash into the system to offset increased liquidity preference. In contrast, Krugman argues that any additional cash injection would have been passively absorbed into inactive balances.21 This argument was to be re-run in the 2000s. There was the same confidence that, because ‘scientific’ monetary policy had supposedly kept inflation low during the years of the Great Moderation, it could raise the rate of inflation to offset the collapse of 2008–9.

The First World War challenged not only the traditional view of monetary policy, but also the Victorian ideal of the minimal state. The two were related: sound finance was needed to maintain sound money. As a result of the war, state expenditure, fiscal deficits, inflation and the national debt all rose to heights not seen since the Napoleonic wars. Viewed through Victorian spectacles, they all seemed part of the same disorder.

This ‘involuntary’ growth of the state was initially assumed to be a wartime anomaly. But enhanced social provision was plainly here to stay. After the war military spending was slashed, but UK central government spending in the 1920s, at 25 per cent of GDP, was almost double its pre-war level. This meant that the government’s fiscal operations had a larger impact on the economy, for good or ill. However, although budgets were larger, governments continued to believe that they should be balanced, the balance including a sum set aside to repay a national debt hugely swollen by the war. Interest rate payments on the debt, and sinking fund, now claimed over 30 per cent of the budget. Adherents of the balanced budget believed that only by confronting advocates of new expenditure with the need to raise the money from taxes could there be a check on the inexorable growth of public spending.

The state of the British economy made it increasingly hard to maintain this approach. Pre-war Britain was accustomed to a ‘normal’ unemployment rate of about 5 per cent. In the interwar years, unemployment among insured workers averaged 10 per cent. Superimposed on this were three cyclical downturns, in 1921–2, 1929–32 and 1937–8. Much of the core unemployment was structural, resulting from a decline of British staple exports – coal, textiles, metals, shipbuilding – and the failure of new products to establish themselves. There would have been severe problems of structural adjustment in any case. But the fragile economy was hit by both supply and demand shocks. A once-and-forall increase in unit labour costs between 1919 and 1922 was never reversed; and aggregate demand was reduced by the policy of deflation to regain and then maintain the gold standard. Structural adjustment would have been easier had Keynes’s recipe of low interest rates and a ‘managed’ exchange rate been followed, but for most of the interwar years ‘abnormal’ unemployment was treated as a cyclical problem that would soon disappear. Policies most frequently recommended were to remove the obstacles to adjustment such as war debts and reparations, tariffs, and the over-generous unemployment benefits which hindered labour mobility and wage flexibility. Otherwise it was a matter of emergency measures.

By June 1921, 2.2 million people were out of work – an unemployment rate of 22 per cent – and Britain experienced a then record peacetime budget deficit of 7 per cent of GDP. The Lloyd George coalition government set up a Cabinet Committee on Unemployment, which made several proposals for increasing public spending. Particularly striking was one in December 1921 by Sir Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India, that the government should deliberately budget for a deficit by reducing income tax, with the expectation that the borrowing requirement would decline as the tax cuts revived the economy, and therefore the government’s revenue.22 Lloyd George’s own preference was to invest in large public works programmes; these counted as capital expenditure and so would not affect the Chancellor’s budget for current spending. It was against these supposedly improvident plans that the ‘Treasury View’ defined itself. In a note to Lloyd George’s Committee, Sir Otto Niemeyer, Controller of Finance at the Treasury, explained that unemployment was not due to insufficient demand, but excessive wage costs. ‘The earnings of British industry are not sufficient to pay the present scale of wages all round. Consequently if present wages are to be maintained a certain fraction of the population must go without wages. The practical manifestation of which is unemployment.’ Niemeyer also warned that a ‘very large proportion’ of any additional borrowings would be diverting money which would otherwise have been used ‘soon’ by private industry.23

These arguments carried the day. Under intense pressure to cut taxes while simultaneously balancing the budget, the government in 1921 appointed Sir Eric Geddes to head a committee charged with finding additional savings of £100 million a year (over £3 billion in today’s money). In what became known as the ‘Geddes Axe’, government spending was slashed over the next five years, thereby undermining an already fragile economy.24 Defending the Axe, Stanley Baldwin, the new Chancellor, repeated that ‘money taken for government purposes is money taken away from trade, and borrowing will thus tend to depress trade and increase unemployment’.25 But, contrary to the reasoning behind the Geddes Axe, the cuts in government spending, by causing a depression, increased the national debt – from 135 per cent of GDP in 1919 to 180 per cent in 1923. The economy bounced back after a year, but never regained anything like full employment for the rest of the 1920s. Budget balance, as it was then understood, was never restored, because the sinking fund was either reduced or suspended.26 This dismal sequence was to be repeated after the crash of 2008.

But what is meant by balancing the budget? The difficulties of doing so in the 1920s, in the face of stagnant revenues and rising social expenditures, led to an increase in ‘off-budget’ accounting. Local authorities and quasi-government agencies borrowed for houses, telephones, roads and public utilities. There was an Unemployment Insurance Fund, which was supposed to ‘balance’ in normal times. These extra-budgetary expenditures were not counted as part of the deficit. The budget that the Treasury concentrated on balancing was the current spending budget. The Treasury’s condition for authorizing borrowing by local authorities and public utilities until at least 1935 was that the money return on investment should be enough to pay both interest and capital on the loan, and therefore not add to the national debt. There was no published figure of Net Public Sector Borrowing until 1968. So the real question was not whether there should be a budget deficit, but what the effects of borrowing outside the central government’s budget would be on the economy. This was the issue raised by the Lloyd George ‘pledge’ of 1929.

In the run-up to the General Election of 1929, the Liberal leader Lloyd George promised that a Liberal government – the Conservatives then being in power – would borrow £250 million for a three-year programme of infrastructure development. This, he claimed, would reduce unemployment ‘in the course of a single year’ to normal proportions, that is, get rid of what was then called abnormal unemployment. This borrowing was to be ‘off budget’, most of it coming from the Road Fund, which would borrow £145 million against its income of £25 million. Much of the road programme and associated land use improvements would produce no direct financial return, but the increase in the Road Fund’s revenue from motor vehicle taxation year by year would be enough to ‘meet the interest and sinking fund on the loan’.27 Keynes and his fellow-economist Hubert Henderson wrote an enthusiastic endorsement, ‘Can Lloyd George Do It?’28 The extra spending, they argued, would create a ‘cumulative wave of prosperity’. The Conservative Chancellor, Winston Churchill, turned to the Treasury for advice. He thought the Lloyd George–Keynes proposals made a lot of sense.

To refute the expansionist argument, the Treasury dusted down a half-forgotten article of 1925 by its only professional economist, Ralph Hawtrey.29 Hawtrey is credited with crystallizing the traditional Treasury prejudice against ‘wasteful’ government expenditure into a formal ‘Treasury View’. He had stated one part of the Ricardian doctrine with Ricardian clarity in 1913: ‘the Government by the very act of borrowing for [state] expenditure is withdrawing from the investment market saving which would otherwise be applied to the creation of capital’.30 This was dubbed at the time a ‘fallacy’ by no less an authority than Arthur Pigou, Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge. Pigou asserted that in a slump capital lies idle.31

In his more nuanced exposition in 1925, Hawtrey claimed that government borrowing of ‘genuine savings’ would crowd out an equivalent amount of private investment.32 The government could create additional employment only by ‘inflation’ (expanding the quantity of money), because this would create additional bank ‘savings’, allowing banks to expand credit to private borrowers. But in this case it was the monetary expansion which was crucial. Public works were simply a ‘piece of ritual’.33 Taking its cue from Hawtrey, the Treasury equipped Baldwin’s government with a standard response to the Lloyd George proposals: ‘we must either take existing money or create new money’. State spending on public works would either be diversionary or inflationary. And inflation was ruled out by adherence to the gold standard. Suitably primed, the Chancellor rubbished the Lloyd George plan by stating:

The orthodox Treasury view . . . is that when the Government borrow[s] in the money market it becomes a new competitor with industry and engrosses to itself resources which would otherwise have been employed by private enterprise, and in the process raises the rent of money to all who have need of it.34

Neither of Hawtrey’s alternatives was correct. If private capital is asleep, as Mill, and even Say, recognized might happen, extra borrowing by government need neither produce inflation nor divert ‘savings’ from existing uses. However, the Treasury adopted the hardest (Ricardian) version of Say’s Law, which was well below the analytical standard of even the orthodox economists of the day.

Could Lloyd George’s plan have reduced unemployment to its ‘normal’ level? The argument turns on the size of the so-called fiscal multiplier: the ratio between an increase in government spending and the corresponding change in national income (see below, p. 133). There are two views. On the one hand, the extra money the government spends will go into the pockets of workers, contractors, suppliers, etc., who will then go on to spend this extra money, ‘multiplying’ the impact of the original injection. On the other, government spending might simply replace, discourage or otherwise ‘crowd out’ private expenditure and cancel out its own impact, especially if the economy is operating at full capacity. In this case the multiplier would be zero; or even negative, if the government spending caused a crisis of confidence.

How big was the multiplier? In 1929, no one knew. Keynes wrote in 1933 that 2 was the most realistic estimate of the multiplier at that moment. Every pound spent by the government would increase total output by two pounds.35 But this was four years into the slump, when unemployment had ballooned. In 1929 the multiplier would have been lower, but still positive. Lloyd George’s £250 million might well have created the 500,000 extra jobs claimed for it at the time, enough to have mitigated the impact of the world depression.

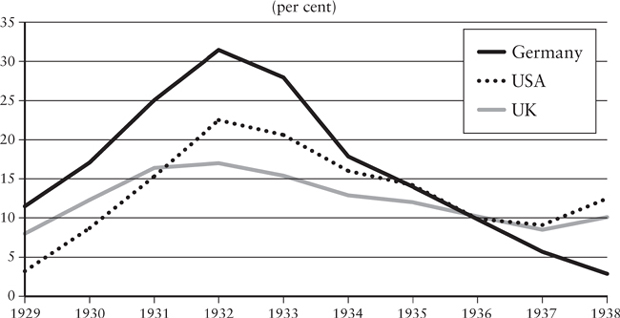

This is denied by Nicholas Crafts and Terence Mills, who estimate that the government expenditure multiplier in the late 1930s was 0.3 to 0.8, much lower than previous estimates.36 They admit their conclusion is ‘model dependent’. A key assumption of their model is that economic behaviour can be characterized by ‘optimizing behaviour by forward-looking households’, which ‘typically expect consumer expenditure to fall rather than increase in response to an increase in government expenditure’, the expenditure ‘shock’ which they have in mind being the announcement of a big rearmament programme. Since these forward-looking households presumably have the correct model of the economy, they will increase their saving in line with their expectation, producing the predicted results. That the size of the fiscal multiplier partly depends on business and household reactions is undeniable. But it is hard to believe that a programme of public investment, targeted on areas of exceptionally heavy unemployment, would have had the nugatory effects claimed by these authors. It is true that in the 1930s a much bigger programme than that envisaged by Lloyd George would have been needed to restore anything like full employment. But that hardly warrants the conclusion that ‘at that point [which point?] there was no possibility of a Keynesian solution to the unemployment problem’. The authors fail to explain how Hitler managed to reduce abnormal unemployment in Germany (from a much higher level than in Britain) to ‘normal’ proportions in the four years 1933–7.37

The minority Labour government elected in 1929 implemented a small part of the Lloyd George programme – far too small to reduce appreciably the rising numbers of unemployment, but enough to alarm the Treasury. In December 1929, the Treasury’s new Controller of Finance, Sir Richard Hopkins, warned against borrowing for road construction: ‘A road, however useful it may be, produces no revenue to the State; it does not provide the interest and Sinking Fund on any loan raised. Accordingly, therefore, according to time-honoured principles of public finance it should be paid for out of revenue.’39

Figure 10. Unemployment rates38

The deepening depression, with unemployment rising from 10.4 per cent in 1929 to almost 20 per cent in 1931, left Philip Snowden, Chancellor of the Exchequer, with a rising budget deficit. He appointed the May Committee to advise him on fiscal retrenchment, and the Committee reported that the government faced a prospective deficit for 1931–2 of £120 million, approximately 2.5 per cent of GDP. It included the prospective deficit of the Unemployment Insurance Fund in the total.40 The Conservative opposition blamed the deficit on the extravagance of the Labour government and demanded cuts in ‘wasteful’ public spending, especially on unemployment benefits. Labour maintained that the hole in the budget was due to the hole in the economy, and the minority government refused to implement the full scale of the spending cuts recommended by the May Committee. As a consequence, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and his Chancellor joined the Conservatives and Liberals in a National Government in August 1931, while Labour went into opposition.

Faced with a prospective deficit for 1931–2 that had been revised upward to £170 million, the National Government legislated a £81.5 million increase in taxes, and spending cuts of £70 million, leaving a projected deficit of £18.5 million. According to Chancellor Snowden, ‘An unbalanced budget is regarded as one of the symptoms of national financial instability.’ This was the end of the attempt to pay back debt. It also marked the end of the gold standard. Sound finance was supposed to maintain confidence in the currency, but the government’s economy measures failed to prevent a continuing flight from sterling, as the merchant banks of the City of London were seen to have borrowed short, and lent long to failed and failing banks on the continent of Europe. No foreign funds were available to ‘bail out’ the City of London, and the obligation to exchange sterling for gold was suspended on 21 September 1931, never to be restored. Release from the ‘golden fetters’ liberated monetary policy. Bank Rate came down from 6 per cent to 2 per cent in 1932. Free trade was also abandoned with the Import Duties Act of the same year. Thus the three pillars of Victorian finance – sound finance, sound money and free trade – crumbled, not from conviction but under the pressure of extreme events.

A combination of devaluation, cheap money and protectionism led to a recovery. Recovery produced balanced budgets from 1933 to 1937, but unemployment was slow to come down (though it was increasingly confined to the north of England, Wales and Scotland). Lloyd George went on trying, campaigning for a big public works programme in 1935. But the Conservative Chancellor, Neville Chamberlain, stuck to the older orthodoxy that state spending was au fond wasteful, and refused to allocate more than a tiny dollop of money to the ‘special areas’ of exceptionally high unemployment. And the Treasury itself was still worried in 1937 that borrowing might lead to a spike in interest rates. There was another economic collapse in 1937–8. A £400 million, five-year loan-financed rearmament programme, representing about 5 per cent of GDP, finally lifted Britain out of semi-slump, ten years after the start of the Great Depression. A threat to national security can always be relied upon to abolish worries about the deficit. With Hitler on the prowl, patriotic citizens rushed to invest in war bonds.

Roger Middleton has argued that the tenacity of the balancedbudget rule was based on four beliefs:

1. that ‘all factors of production are normally and inevitably utilized by private business’;

2. that unbalanced budgets, especially if incurred for ‘wasteful’ public works, would reduce business confidence;

3. that unbalanced budgets were likely to be inflationary; and

4. that the national debt implied a deadweight loss to productive enterprise.41

These were the arguments of Ricardo, and almost exactly the arguments used by George Osborne’s Treasury in 2010. However, the Treasury’s ability to run budget surpluses in the mid-1920s was critically dependent on ‘window dressing’ the accounts. The Sinking Fund Act of 1875 required the setting aside of ex ante planned surpluses to redeem the national debt. By manipulating the estimated sinking-fund target, the Chancellors of the 1920s were able to accommodate the demands for greater social expenditure under the constraints of the balanced-budget rule. The budget identity ‘had become an amorphous hybrid, an amalgam of current and capital accounts, devoid of any internal consistency or tangible economic significance’.42

In 1931 Keynes struck a new note. ‘Look after unemployment,’ he said, ‘and the budget will look after itself.’

The Great Depression of 1929–32 marks the divide between the pre-Keynesian and post-Keynesian worlds of policymaking. Keynes had been appointed a member of the Macmillan Committee on Finance and Industry, set up to enquire into the causes of the deepening slump. His interrogation of officials of the Bank of England and the Treasury in May 1930 was a key confrontation between the old and the new theories of macroeconomic policy.

The chief importance of the Macmillan Committee hearings for Keynes’s thinking was that it shook his faith in monetary policy. Hitherto he had regarded monetary policy as key to preventing or modifying the ‘credit cycle’; fiscal policy was ‘second best’, necessitated by the constraints of the gold standard. Now, his emphasis shifted to fiscal policy, with monetary policy in a purely supporting role.

Much to Keynes’s surprise, representatives of the Bank of England stolidly denied that the Bank had the power over credit conditions that Keynes, like other monetary reformers, had claimed for it. Bank rate, declared the Governor of the Bank, Montagu Norman, affected only ‘short money’, leaving the ‘whole mass of credit’ little changed. Another Bank official, Henry Clay, elaborated on Norman’s laconic performance:

while the conditions of sound banking impose a limit on the amount of credit, the origin of credit is to be found in the action of the businessman, who approaches the bank for assistance with a business transaction, and the basis of credit is the probability that the transaction can be done at a profit.

‘What you are saying’, Keynes objected to the Bank official Walter Stewart, ‘is that there is always the right quantity of credit?’ Stewart doubted whether ‘the expansion of bank credit in quantity was a determining factor in prices and trade activity . . . there are a great many things that people can do with money besides buying commodities. They can hold it.’ All that meant, Keynes rejoined, was that the Bank would have to ‘dose the system with money’ and ‘feed the hoarder’, in order to bring down long-term rates. To which Stewart responded: ‘I should not have thought that bank credit determines the long-term rate.’ Keynes admitted that when a depression had got too deep, a ‘negative rate of interest’ might be required to bring money out of hoards, but normally ‘a reasonably abundant supply of credit would do the trick’. Stewart persisted: ‘Only if borrowers saw a prospect of making a profit and of repaying debts.’ Keynes was driven to arguing that ‘though [the supply of credit] may be only a balancing factor, it is the most controllable factor’. To which Stewart replied, ‘It may be the only thing that the Central Bank can do; but it does not strike me as being the only thing that business men can do . . . I regard wage adjustments as ever so much more important . . . [than] anything bankers can do.’ The Bank was denying that, unaided, it could rescue an economy from a slump.43 Exactly the same issue, with the same arguments on both sides, re-emerged with quantitative easing (QE), following the economic collapse of 2008–9. Such is progress in economic science!

Keynes’s belief in monetary therapy was shaken, but not shattered. He still believed that when interest rates were lowered a new range of investment projects would become profitable. But he admitted that bank rate was a weaker instrument for securing lower rates than he had believed. It was all very well to talk of ‘feeding the hoarder’, but suppose his appetite was insatiable? The result would be a credit deadlock. By 1932 he was writing:

It may still be the case that the lender, with his confidence shattered by his experience, will continue to ask for new enterprise rates of interest which the borrower cannot expect to earn . . . If this proves to be the case there will be no means of escape from prolonged and perhaps interminable depression except by direct state intervention to promote and subsidise new investment.44

This passage marks the defeat of the hopes of the monetary reformers. It is not money which controls expectations about the economy; it is expectations about the economy which control expectations about money. In a deep slump it was no longer enough to manage expectations about the future of the price level; the expectations which needed managing were about the future of output and employment. This required fiscal policy.

But fiscal policy to fight the slump offered its own obstacle in the form of the Treasury View, presented at the Macmillan Committee by the formidable Sir Richard Hopkins. Keynes thought he knew what the Treasury View was, and that he was in a position to refute it. The Treasury had claimed that loan-financed public spending could not add to investment and employment, only divert them from existing uses. This was true, Keynes was prepared to say, only on the assumption of full employment. But Hopkins had foreseen this.

The Treasury was not opposed to government borrowing as such, Hopkins told Keynes; it was not even claiming that all private capital was being used. Its objection was to the particular plan put forward by Lloyd George. This plan, ‘far from setting up a cycle of prosperity’ as Keynes had hoped, would much more probably ‘produce a great cry against bureaucracy’ and capital would flee the country, so the loans would have to be ‘put out at a very high price’. Was not the Lloyd George plan likely to retard the necessary fall in interest rates? Well, Keynes persisted, suppose instead of borrowing the money from the public, the government borrowed it from the Bank of England. That was ‘fantastic’, Hopkins replied: ‘If I am right in thinking that a great loan directly raised in the ordinary way would carry with it a bad public sentiment and adverse repercussions . . . what would happen if it were raised by what is ordinarily called plain inflation I cannot imagine.’ The chairman, Lord Macmillan, concluded: ‘I think we can characterize it as a drawn battle.’45

Let’s stand back for a moment. What Hopkins had done was to invoke what Paul Krugman in 2010 called ‘the confidence fairy’:46 the view that the effects of a budget deficit on the economy depend on the expectations of the business community. More broadly, any policy had to take into account the psychological reaction to it. This is to say that the success of a policy depends on the model of the economy in the minds of the business community. If they believe that a government loan-financed programme of capital investment will make things worse, they will react in a way that will make things worse. It was not the state’s borrowing per se, but loss of confidence in government finance implied by that borrowing, which would create the ‘hole’ in private capital.

There is no doubt that Keynes was disturbed by Hopkins’s confidence fairy. Experience of slump was not itself sufficient to loosen the hold of the old religion. That could be done only by a different model of the economy. Keynes’s General Theory of 1936 was the attempt to create that different model.

In a letter to a correspondent, dated 22 November 1934, Keynes wrote that the differences between economists ‘strike extremely deep into the foundations of economic theory’. He continued:

The difference is between those who believe in a self-adjusting economy and those who don’t. Those who do will always argue for non-intervention in order to allow freedom to economic factors to bring about their own self-adjustment . . . But just because the differences go so deep there is no chance of convincing the opposition until a new scheme of economic theory has been developed and worked out. In the past we have been opposing the orthodox school more by our flair and instinct than because we had discovered in precisely what respects their theory was wrong.47

It was to explain precisely why the classical theory was wrong that Keynes wrote his new book. It was Depression itself which gave a radical edge to his critique. The classical theory, he mused, abstracted from the problem of unemployment by assuming there was no unemployment to explain.

The simplest, easiest to understand and, therefore, generally most acceptable version of Keynes’s argument is his demonstration that economies adjust to a ‘shock’ to investment demand by a fall in income and output, leading to ‘under-employment equilibrium’. ‘Quantities adjust, not prices’ was the headline version of Keynes’s model. In the classical models, adjustment always means a restoration of a unique (optimal) point of equilibrium through movements of relative prices. The theoretical novelty in Keynes’s treatment lay in the claim that, when the desire to save exceeds the desire to invest, the only adjustment path open is through a change in aggregate income and output. The excess saving at the initial equilibrium level of income is eliminated by the fall in income, creating a situation of stable output at less than full employment.

Although in this under-employment equilibrium saving equals investment, as in the classical equilibrium, the causation is reversed. In the classical scheme, the amount of investment is governed by the amount of real resources that households are willing to withhold from current consumption to secure greater wealth in the future. In Keynes’s theory, saving is a consequence, not a cause, of investment. The amount of investment determines the level of income; and the level of income determines the amount of saving, via the marginal propensity to consume.

In the General Theory there are no banks. The action moves directly from a shock to investment to a fall in income. But Keynes understood that the volume of investment is determined by the expected rate of return on investment – what he called the ‘marginal efficiency of capital’ (MEC) – compared with the terms on which banks provide finance for it (the market rate of interest). Investment will be pushed to the point where the marginal efficiency of capital equals the market rate of interest. If the rate of interest is 3 per cent, no one will pay £100 for a machine unless he expects to add £3 to his annual net output, allowing for costs and depreciation. So how much new investment takes place in any period will depend on those factors which determine the expected rate of return and the market rate of interest. Here, Keynes distinguishes between the borrower’s risk and the lender’s risk. The borrower’s risk ‘arises out of doubts in his own mind as to the probability of his actually earning the prospective yield for which he hopes’. But in any system of borrowing and lending one must take into account the lender’s risk, which arises from the possibility of a default. Thus the financing of investment by the banks involves a duplication of risk which would not arise if the investor were venturing his own money. A shock to confidence could reduce both the supply of finance from the banks and the demand for it. Nevertheless, Keynes regarded changes in the borrower’s expectation of risk as much the most important in explaining fluctuations in investment. It is through the MEC that ‘the expectation of the future influences the present’; and it is the dependence of the MEC on changes in expectations which renders it ‘subject to . . . somewhat violent fluctuations’.48

Keynes comes to the heart of his explanation of economic collapse in his discussion of Say’s Law. Paul Krugman rightly says that the ‘demolition of Say’s Law’ that ‘supply creates its own demand’ is the ‘crucial innovation’ in the General Theory. The law is ‘at best a useless tautology when individuals have the option of accumulating money rather than purchasing goods and services’.49 But ‘why should anyone outside a lunatic asylum wish to use money as a store of wealth?’ Keynes asks. His answer is that investment falls with the rise of uncertainty – the rise of which is signalled by the increased demand for cash.50 Uncertainty in the General Theory is not just confined to those transition periods when the value of money is changing. It is present in all transactions of a forward-looking character.

In his account of the psychology of investment, both in chapter 12 of the General Theory and in a Quarterly Journal of Economics article (‘The General Theory of Employment’) of February 1937, Keynes breaks decisively with the neo-classical model of rationality, in which agents with perfect foresight accurately calculate the risk they run by committing present funds to secure future income streams. Because investors do not know the risks they are running (but only pretend to), investment is subject to steep and sudden collapses when their false confidence in the pretence evaporates. ‘New fears and hopes will, without warning, take charge of human conduct. The forces of disillusion may suddenly impose a new conventional basis of valuation.’51 With investment governed by flimsy ‘conventions’ and ‘animal spirits’, full employment is reached only in ‘moments of excitement’. ‘Thus’, Keynes wrote, ‘if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die; – though fears of loss may have a basis no more reasonable than hopes of profit had before.’52

Keynes used the example of a newspaper beauty contest to illustrate the conventional character of investment decisions. Here the prize goes to the reader who chooses not the face he thinks prettiest, but the face which he thinks likeliest to be chosen by the other readers. What we think of as objectivity is trapped within the circle of expectation. Speculation, though, is more like the Victorian parlour game of Old Maid. In this game, the aim of each player is to avoid being left holding the Old Maid (a card without a match) when the music stops. No one wants to be left with the bad investment, but no one knows when it will turn up. So the aim of each player is to make a profit and run.53

It is tempting to relate Keynes’s ‘conventions’ to what orthodox economics calls ‘fundamentals’, and ‘animal spirits’ to ‘irrationality’. According to this view, agents price share values ‘correctly’ on average, with deviations being mistaken or irrational. But this was not Keynes’s view. Conventions and animal spirits alike are grounded in uncertain expectations concerning the future money value of transactions. In a monetary economy, they never escape the circle of money to reach supposedly underlying ‘fundamentals’.54

If a collapse is characterized by a situation in which the supply of saving exceeds the demand for investment, it would be reasonable to expect, as did the orthodox theory, that a fall in the price of saving (the rate of interest obtainable from lending out saving) would rebalance (or equilibrate) the two at an unchanged level of income. Households will save somewhat less and consume more; businesses will take advantage of lower interest rates to borrow more. Keynes’s crucial insight was that the rate of interest reflects the demand for money, not the supply of savings. In Keynes’s terms, if liquidity preference rises, a higher rate of interest will be required to induce lenders to part with money, and this will prevent the interest rate falling sufficiently to restore a full employment level of investment. As Keynes explained, the interest rate is ‘a measure of the unwillingness of those who possess money to part with their liquid control over it’. It is ‘the inducement not to hoard’.55 Thus the rate of interest cannot play the equilibrating role assigned to it in the neo-classical theory.

In his discussion of the role of money, Keynes takes a view of the nature of money that is diametrically opposed to the ‘real analysis’ of the classical school, as set out in Chapter 1 of this book. For exponents of the ‘money as veil’ view, there can be no such thing as liquidity preference, or a desire for money distinct from a desire for the goods that money can buy. According to Keynes, though, money ‘in its significant attributes [my italics] is, above all, a subtle device for linking the present to the future’.56 People accumulate money rather than spend it, because they regard the future as uncertain and therefore hoard money as security against uncertainty. If the future were perfectly known, there would be no rational – as opposed to a psychological-neurotic – reason for ‘holding money’, or indeed for money at all. It follows from this view of money that the role of financial institutions is not to intermediate between savers and investors, but to provide liquidity, as and when it is needed – at a price. The rate of interest in Keynes’s theory is the price of liquidity, not saving.

Keynes also explained why flexible money-wages would not maintain full employment. In the orthodox scheme, the price of labour was assumed, like the price of everything else, to fluctuate with the quantity demanded. Classical economists reasoned that the demand curve for labour, like the demand curve for apples, was downward sloping: the lower the price the more would be sold. Unemployment could thus be explained by the existence of ‘sticky’ wages: the refusal or slowness of labour in adjusting their wage demands to the new situation. However, wages were not uniformly ‘sticky’. Between 1929 and 1932 moneywages in the United States fell by 33.6 per cent, but unemployment kept rising the whole time. ‘It is not very plausible’, Keynes commented, ‘to assert that unemployment in the United States was due . . . to labour obstinately refusing to accept a reduction of money wages.’57 The classical view that if wages fell employment would be increased referred to real wages (W/P – nominal wage divided by price level). But workers bargained for money, not for real wages. They were in no position to reduce their real wage as a whole in a slump by accepting a reduced money-wage, because an all-round reduction in money-wages would simultaneously reduce prices ‘almost proportionately’, leaving the real wage, and therefore the labour surplus at that wage, unchanged.58 Unless employers had reason to believe that a reduction in moneywages would be followed by a rise in the price level, they would have no reason to provide additional employment.59 The argument had a flaw, for a fall in the general price level would increase the value of cash holdings (M/P – money divided by price level), which would, at least to some extent, offset the depressive effect of the fall in money-wages. As we shall see, the non-Keynesians were able to exploit this gap in Keynes’s analysis to reinstate the logical integrity of the neo-classical wage-adjustment story. Keynesians were left with a ‘sticky wage’ story, which was certainly sufficient to justify short-run Keynesian policy to increase money demand, but left the neo-classical theory free to continue to assert that, with perfectly flexible money-wages, economies would always recover naturally from shocks.60

Keynes did not condemn the whole corpus of inherited economics; he only wanted to to fill the ‘gaps’ in what he called ‘the Manchester system’. He wrote:

If we suppose the volume of output to be given, i.e. to be determined outside the classical scheme of thought, then there is no objection to be raised against the classical analysis of the manner in which private self-interest will determine what in particular is produced, in what proportions the factors of production will be combined to produce it, and how the value of the final product will be distributed between them. Again, if we have dealt otherwise with the problem of thrift, there is no objection to be raised against the modern classical theory as to the degree of consilience between between public and private advantage in conditions of perfect and imperfect competition. Thus, apart from the necessity of central controls to bring about an adjustment between the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest, there is no more reason to socialise economic life than there was before.61 [my italics]

This passage deserves more contextual consideration than it has received. Keynes was not identifying ‘modern’ (i.e. neo-) classical economics with laissez-faire. He implicitly conceded that within this corpus were to be found some arguments for ‘socialising’ economic life, to do with the existence of imperfect competition and public goods; only these were not the arguments which concerned him, because they were irrelevant to the problem which did concern him – namely, the existence of continuing mass unemployment.

Keynes’s concessions to neo-classical economics were not enough to placate some of his supporters. Economists like Roy Harrod, who wanted to reconcile Keynes’s theory to neo-classical theory, tried to persuade him that the important difference between the two concerned the relative speed and strength of income adjustments and price adjustments. Keynes stuck to his guns, by denying that there were any price adjustments at all, however weak and slow-moving, capable of restoring a shocked system to full employment in any reasonable period of time. Only at the bottom of the slump, after income adjustment had done its work, did relative prices start to move, though only to a limited extent. In the controversies following the publication of the General Theory, he was moved to observe ironically: ‘I hear with surprise that our forebears believed that cet. par. an increase in the desire to save would lead to a recession in employment and income and would only result in a fall in the rate of interest in so far as this was the case.’62

Keynes’s economics was deeply embedded in his ethics. His insistence on maintaining maximum employment was driven by the thought that the quicker the accumulation of wealth could be made to happen, the sooner people would be able to escape from the burden of drudgery – or mechanical work – into fulfilling lives. He looked forward to the day when capital would be so abundant that people would no longer be compelled to ‘work for a living’.63

Keynes called his book the ‘general’ theory, because he took uncertainty to be the general case, with full information as the special case. Thus, under-employment was not a lapse from a normal condition: it was the normal condition, interrupted only by ‘moments of excitement’. The task of policy was to move the economy from the inferior equilibrium it naturally gravitated towards if ‘left to itself’, to the superior equilibrium which was available by purposive public action. Provided the aggregate supply curve was not completely inelastic, the government could, by an injection of autonomous demand, move the economy to a superior equilibrium. The General Theory thus marked the birth of macroeconomic policy as it was pursued until the 1970s. (The contrast with the classical theory of economic policy is modelled in Appendix 5.1, p. 132.)

By what set of instruments was this improved equilibrium to be brought about? In conventional macroeconomics the government can act on the level of activity through monetary policy, fiscal policy and exchange-rate policy. Reacting against the inordinate hopes of the monetary reformers, Keynes discarded monetary policy as the primary economic regulator. He now doubted the ability of the monetary authority to get interest rates low enough and prices high enough to offset a marked rise in liquidity preference. However, there was a role for monetary policy in ‘normal’ times, which was to maintain continuously low long-term interest rates. For this reason, Keynes opposed the use of ‘dear money’ to check a boom. The effect of a rise in the interest rate on the yield curve would be very difficult to reverse.

A low enough long-term rate of interest cannot be achieved if we allow it to be believed that better terms will be obtainable from time to time by those who keep their resources liquid. The long-term rate of interest must be kept continuously as near as possible to what we believe to be the long-term optimum. It is not suitable to be used as a shortperiod weapon.64

In arguing for the continued (if now limited) power of monetary policy over interest rates, Keynes reverted to the ideas of the Tract on Monetary Reform and A Treatise on Money. The Quantity Theory of Money continued a ghostly existence in the General Theory, as seen in Keynes’s liquidity preference equation

M = L(Y,r)

where the demand for money (L) is assumed to vary with the rate of interest (r) and money income (Y), but where the supply of money (M) is exogenously given, as in the quantity theory.65 At a given level of money income, the rate of interest equilibrates the demand for cash with the supply of cash. By feeding the hoarder with money, the central bank can prevent the rate of interest rising to choke off investment. Contrary to most Keynesians, Keynes himself believed that some important classes of investment, particularly real estate, were interest-elastic (sensitive). He therefore welcomed the policy of cheap money made possible by leaving the gold standard in 1931, which helped, by starting a housing boom, to lead the way out of the slump. However, unlike the monetary reformers, he did not believe that a policy of low interest rates alone was enough to bring about complete recovery from a slump. Real interest rates in the UK were negative from 1932 until 1937, but unemployment was still 10 per cent in the latter year.

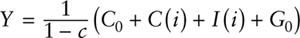

Despite Keynes’s obeisance to his past as a monetary reformer, the main policy message of the General Theory was that the most powerful and direct way a government could influence the level of spending in the economy is through fiscal policy. The crucial tool for fiscal policy was the multiplier, whose logic Keynes sketched out in chapter 10 of his book, and which is conventionally written:

M = 1/(1–MPC)

where M is the magnitude of the multiplier and MPC the marginal propensity to consume.

By use of the formula, policymakers could calculate how much extra spending needed to be injected into, or withdrawn from, the circular flow of spending to maintain full employment. The multiplier theory is the fiscal equivalent of the Quantity Theory of Money, and, at full employment, is identical to it. (For technical discussion of the multiplier, see Appendix 5.2, p. 133.)

In advocating loan-financed public spending to maintain full employment, Keynes jettisoned the orthodox policy of cutting public spending to balance the budget in a slump. He wrote:

it is a complete mistake to believe that there is a dilemma between schemes for increasing employment and schemes for balancing the budget – that we must go slowly and cautiously with the former for fear of injuring the latter. There is no possibility of balancing the budget except by increasing national income, which is much the same as increasing employment.66

Keynes’s scorn for the reasoning of the deficit hawks spurred him to the following passage:

It is curious how common sense, wriggling for an escape from absurd conclusions, has been apt to reach a preference for wholly wasteful forms of loan expenditure rather than for partly wasteful forms, which, because they are not wholly wasteful, tend to be judged on strict ‘business’ principles. For example, unemployment relief financed by loans is more readily acceptable than the financing of improvements at a charge below the current rate of interest; whilst the form of digging holes in the ground known as gold mining, which . . . adds nothing to the real wealth of the world . . . is the most acceptable of all solutions.

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with bank-notes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise . . . to dig the notes up again . . . there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

. . .

Ancient Egypt was doubly fortunate, and doubtless owed to this its fabled wealth, in that it possessed two activities, namely, pyramidbuilding as well as the search for the precious metals, the fruits of which, since they did not serve the needs of man by being consumed, did not stale with abundance. The Middle Ages built cathedrals and sang dirges. Two pyramids, two masses for the dead, are twice as good as one; but not so two railways from London to York. Thus we are so sensible, have schooled ourselves to so close a semblance of prudent financiers, taking careful thought before we add to the ‘financial’ burdens of posterity by building them houses to live in, that we have no such easy escape from the sufferings of unemployment.67

There was a theoretical and social radicalism in Keynes, obliterated in standard post-war Keynesian discussions. Keynes thought insufficient demand was chronic and would get worse; and that, in consequence, the longer-term survival of a free enterprise system depended on the redistribution of wealth and income and the reduction in hours of work. I will return to these points in Chapters 10 and 13.

On exchange-rate policy, the General Theory offered a powerful implicit argument against the gold standard. As Keynes would later point out, under the gold standard, adjustment was ‘compulsory for the debtor and voluntary for the creditor . . . The debtor must borrow; the creditor is under no such compulsion [to lend].’68 These golden fetters prevented central banks in the debtor countries setting rates of interest geared to domestic needs. The increase in creditor ‘hoarding’ of countries such as the United States and France as the slump deepened prevented a global fall in long-term interest rates that would have helped revive the ‘animal spirits’ of investors.

Keynes’s International Clearing Union plan of 1941 was designed to remedy this defect. The essence of his plan was that creditor countries would not be allowed to bury their gold in the ground, or charge usurious rates of interest for lending it out; rather, their surpluses would be automatically available as cheap overdraft facilities to debtors through the mechanism of an international clearing bank, whose depositors were the central banks of the Union. Creditor countries would be charged rising interest rates on their bank deposits with the Union; persisting credit balances would be confiscated and transferred to a reserve fund. Keynes explained that no country needed to be in possession of a credit balance ‘unless it deliberately prefers to sell more than it buys (or lends)’.69 So no creditor country would suffer injury by having its credit balance actively employed. Keynes’s long-term aim was to replace gold by an international reserve currency, which he called ‘bancor’. By increasing or reducing the quantity of bancor, the clearing bank’s managers would be able to vary it contracyclically and ensure enough global money for trade expansion.70

The General Theory divided the economics profession. Older economists thought Keynes was wrong, or had nothing new to say. Younger economists eagerly embraced the new doctrine as offering hope that full employment could be maintained without recourse to the dictatorships then on offer in Germany and Soviet Russia.

Where does the General Theory fit into the history of thought? The answer is that Keynes was much more of a classical than a neo-classical economist. His interest was in long-run growth, leading to the stationary state in which everyone could give up painful work. He wanted to get there as quickly as possible, which is why he was so keen to secure maximum investment. The classical theory was wrong only in one respect: in insisting on maximum saving rather than maximum investment, in the mistaken belief that the first was the cause of the second. Corrected for this, it was a serviceable guide for thinking and policy. It is true that Keynes’s ‘model’ was a short-run model, but that’s not because he was interested only in short-run stabilization. He wanted a full employment level of investment in the short-run, so as to get to the long-run quicker.

However, there was a serious political-economy gap in Keynes’s thought, which critics would exploit to undermine the Keynesian system. His flows of aggregate income and output were unrelated to the decisions of any actors in the economy. That is to say, they were not ‘micro-founded’ in any individual or class behaviour. On the one side, it was very hard for the older generation of classical economists to see how ‘under-employment equilibrium’ could be a meaningful state of affairs. Surely workers could always get as much employment as they wanted at the going wage? If they refused job offers it was their choice. On the other side, Marxists pointed out that Keynes had failed to realize that capitalists needed a ‘reserve army of the unemployed’ to keep down wages. From both points of view, Keynes had not so much captured the adjustment process as frozen the film at a moment in time. One needed to keep it running to capture the full behavioural dynamics of the economic system.

The story of the Keynesian revolution opens with gold losing the battle to control money. There was either too much or too little of it, causing inflation or unemployment. The monetary reformers of the 1920s had a noble cause. If money could be freed from its golden fetters and control of its issue vested in an independent central bank, there would always be just the right amount of money for the needs of trade. Such a system would be just as good as gold in stopping a government ‘monkeying around’ with the money supply.

What the monetary reformers failed to realize was that the money supply could not be controlled without keeping economic activity steady, because unsteadiness in economic activity would be reflected in swings in the velocity of circulation. This was pointed out by Keynes with great clarity in the General Theory, and it remains the most telling critique of monetary stabilization policy prior to the crash of 2008–9 and the policy of quantitative easing that followed it.

Classical economists said that full employment was the natural condition of a capitalist market economy. Marxists said unemployment was inevitable. Keynes’s great achievement was to demonstrate that unemployment was likely but not inevitable. By inventing macroeconomics, he restored the relevance of economics for a free society.

To be sure, ‘Keynesian’ policy existed both before and apart from Keynes, if by Keynesian one means simply government spending, whose effect is to provide work. The state had been spending money and providing employment ever since government started, a great deal of it for war purposes.71

In Keynes’s own time, Hitler, as Joan Robinson remarked, cured unemployment in Germany before Keynes had finished explaining why it existed; Roosevelt’s New Deal can also be called Keynesian. But the inspiration of such work-providing programmes was political, not economic. Hitler wanted Germany to be at full capacity to prepare for a war of conquest. Roosevelt’s New Deal is an example of pragmatically and politically driven experimentation. As FDR explained in 1936, in language whose eloquence no leader today can match:

To balance our budget in 1933 or 1934 or 1935 would have been a crime against the American people . . . When Americans suffered we refused to pass by on the other side. Humanity came first . . .

. . . We accepted the final responsibility of Government, after all else had failed, to spend money when no one else had money left to spend.72

In such cases, public works programmes were not backed by any theory which showed why they were needed; the classical theory demonstrated they were unnecessary and harmful. Before Keynes, Marxism alone had a theory of unemployment. So Keynes was overthrowing not only existing classical theory but the politics of communism.

The economic context was right for a new theory. Mass unemployment of 20 per cent or more of the workforce demanded intellectual as well as political attention. Marx believed that capitalism’s requirement for a ‘reserve army of the unemployed’ would become intolerable and lead to the overthrow of capitalism. But Marx failed to see the unavoidable consequences of the economic and technological revolution that was going on before his eyes. These consequences, as summarized by Lowe, were

the shift of political power to the middle classes and the rise of strong labour unions . . . capable of making their growing aspirations felt under a system of widening franchise . . . This not only democratized the spirit of modern government but created the new administrative key position for a progressive control of economic by political forces.73

In short, Marx missed the growth of a social balance between business, labour and government, which took the revolution off the agenda. At the same time, the business class lost its ability to enforce the real-wage reductions that it believed to be necessary to its continued profitability. As a result, mass unemployment became endemic in the developed world. This was the setting in which Keynes’s analysis of the economic problem in terms of ‘under-employment equilibrium’ could gain traction. It promised to break the social stasis by invoking the economic power of the state. Both capital and labour would gain from the elimination of under-employment. Although Keynes’s theory undercut the case for state socialism, it opened up the road for government ‘management’ of the macroeconomy to ensure at least a quasi-optimal equilibrium.

Keynes’s theory also undercut the argument for fascism. This aspect of its political work has been little noticed, because few have bothered to study fascist ideology. Fascism distinguished between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ capitalism, a division corresponding roughly to that between national industrial and international financial capitalism. Its attack on international finance was explicitly or implicitly anti-Semitic. It was to this kind of politics that Keynesian thinking offered an antidote, by providing a rationale for keeping banking under national control. Few paused to ponder the political consequences of releasing finance from national regulation in the 1980s and 1990s.

Keynes’s theory could have become the basis of policy only under conditions of social balance. His was the economics of the middle way; the best deal that liberal capitalism could expect in a world veering towards the political extremes. He thought of his economics as the economics of the general interest, for it encompassed, while transcending, the sectional interests of both capital and labour. This is true: it was the least ideological of all economic doctrines, the least dependent on class interest. His political genius was to see that when the problem was one of unused capacity, redistribution was a minor question, which could be postponed until later.

But by the same token, his economics threw little light on what would happen to class income shares when his own policies achieved full employment, in conditions of trade-union control of the supply of labour. In such a situation, would capitalism need to recreate Marx’s ‘reserve army of the unemployed’ to restrain wage demands, or would the government be forced to inflate the economy to keep profits racing ahead of wages? The latter is what the economist Jacob Viner assumed would happen when society got accustomed to full employment.74

Keynes himself admitted that he had ‘no solution . . . to the wages problem in a full employment economy’.75 Marxists, too, believed that attempts to overcome the class struggle by inflation would bring only temporary relief. So the great question which Keynes believed he had settled for his own day remained for the future.

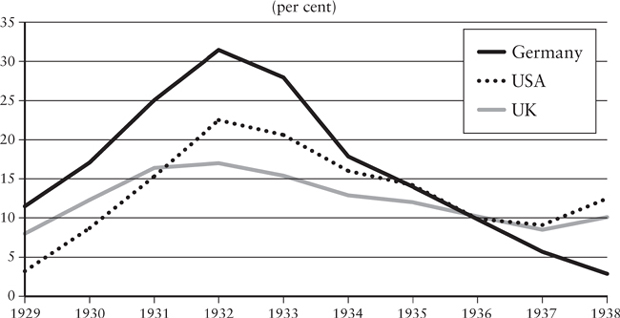

In the classical model, the economy is always at full employment. Because wages and prices are fully flexible, the aggregate supply curve (AS) is vertical. Government intervention is undesirable as any attempt to raise aggregate demand (AD) has no effect on output/employment, but just causes inflation.

In the short-run Keynesian model, wages and prices are highly sticky so the AS curve is horizontal. The level of output/employment depends entirely on the AD curve, so government intervention is desirable, and in fact necessary. The easiest interpretation of Keynes’s message is that, in the face of a negative shock, supply fails to adjust to the fall in nominal demand, so unemployment could develop, and even persist. Eventually supply would adjust (in the long-run, the AS is vertical, as prices have fully adjusted), but it would be better for the government not to allow any fall in nominal demand in the first place.

Figure 11. Keynes’s short-run supply and demand curve

The minimum doctrine to justify policy intervention to stabilize economies can be summarized as follows:

For Keynes, it was the tendency for the private sector, from time to time, to want to stop spending and to accumulate financial assets instead that lay behind the problems of slumps and unemployment. It could be checked by deficit spending . . .

. . . In the standard Keynesian economic model, when the economy is at less than full capacity, output is determined by demand; and the management of economic activity and hence employment is effected by managing demand.76

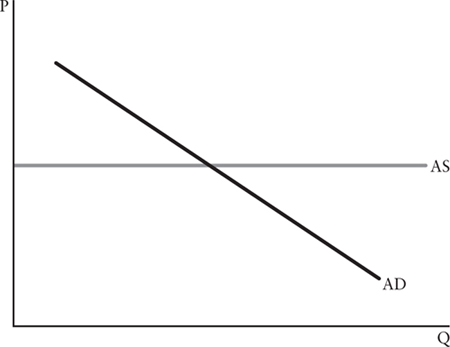

The fiscal multiplier measures the effect of a change in fiscal policy on real national income. Let us consider a closed economy:

Y = C + I + G

In the Keynesian framework the consumption equation takes this form:

C = C0 + cY

Where C0 is autonomous consumption and cY is the part of consumption which is explained by the level of disposable income. c represents the marginal propensity to consume, and it takes a value between 1 (all available income is consumed) and 0 (all available income is saved).

Investments are supposed to be dependent on exogenous factors (i.e. expected profitability or ‘animal spirits’):

I = I0

Government spending is autonomous by definition:

G = G0

Inserting the functional forms of C, I and G in the expenditure identity, and rearranging, gives:

Every variable within the parenthesis represents an autonomous component of aggregate demand. Therefore, with a variation in one of these (e.g. fiscal expansion +ΔG0), the expression  captures the value of its multiplier effect on Y. As 0 < G < 1, the denominator also takes a value lower than 1, but still positive. The overall multiplier will therefore take a value ≥ 1.

captures the value of its multiplier effect on Y. As 0 < G < 1, the denominator also takes a value lower than 1, but still positive. The overall multiplier will therefore take a value ≥ 1.

Y = 100, C0 = 30, I0 = 10, G0 = 10 and c = 0.5 so that the expression  .

.

Let us assume an increase in fiscal spending so that G0 = 12, implying ΔG0 = +2. Aggregate demand and income +ΔG will increase by +4 units, not only by the 2 additional ones implied by +ΔG0.

The result will be Y = 104, as 104 = 2(30 + 10 + 12).

The value of the multiplier is 2:

and it affects positively and more than proportionally an increase in the autonomous components of demand.

Let us consider again a closed economy:

Y = C + I + G

In the neo-classical theoretical framework the consumption equation might take this form:

C = C0 + C(i) + cY

The new variable C(i) represents the part of overall consumption which is determined by the rate of interest. Consumption falls as the interest rate increases, and vice versa:

In the pure form (without any accelerator effect of AD on I), investments are negatively dependent on the rate of interest

I = I(i)

Government spending remains as the only autonomous component of demand:

G = G0

Inserting again the functional forms of C, I and G in the expenditure identity, and rearranging, gives:

This time, represents only the multiplier effect of a variation in the autonomous component of consumption C0, as the other component G0 is supposed to produce changes in the value of C(i) and I(i).

represents only the multiplier effect of a variation in the autonomous component of consumption C0, as the other component G0 is supposed to produce changes in the value of C(i) and I(i).

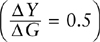

In particular, an expansionary fiscal policy is supposed to produce a ‘crowding out’ effect on consumption and investment, by negatively impacting on the rate of interest.77