The effect of distribution on the performance of the economy was the main topic of classical economics. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations raised the question of how the distribution of the national product between landlords, capitalists and workers determines the growth of wealth. This was taken up by Ricardo and Marx. According to these economists, the class character of distribution enlarged or restricted economic growth. For example, for Ricardo the rent of landlords was both unearned and misspent; the bigger their rent, the less would be left for capitalist accumulation, the real source of economic growth. Governments were considered to be mainly agents of the landlord class.

With the marginalist revolution of the late nineteenth century, distribution became detached from the macroeconomy, being subsumed in the discussion of allocative efficiency. Replying to Marx’s charge that the capitalist exploited the worker, the American economist John Bates Clark, in his 1899 book The Distribution of Wealth, used a simple aggregate production function to show that, in a competitive market equilibrium, the two factors of production, capital and labour, would be paid their marginal products – that is, in proportion to their contribution to satisfying individual preferences.1 Distribution was off the economic agenda.

Recently, discussion of distribution has centred on the fact, and meaning, of the sharp rise in inequality since the 1970s, particularly in the United States and Britain. The most notable contributions here are Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), a documentation of long-run trends in the distribution of wealth and income in developed capitalist economies, and Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler (2017).2 Piketty’s data show both a widening dispersal of incomes and a fall in labour’s wage share since the 1970s and 1980s. For Scheidel, whose history of inequality stretches back to the Stone Age, inequality is humanity’s natural condition, interrupted only by wars, revolution, state failure and lethal pandemics. Both attribute the ‘great compression’ of wealth and incomes in the middle years of the last century to the effects of the two world wars and Great Depression. What Scheidel calls ‘disequalization’ since 1980 is simply the resumption of normal conditions.

Neglected by contemporary economic textbooks are the macroeconomic effects of growing inequality. This was the missing dimension in the standard explanations of the recent recession. The reason is that standard growth models dismiss recessions as temporary blips on long-run trends.

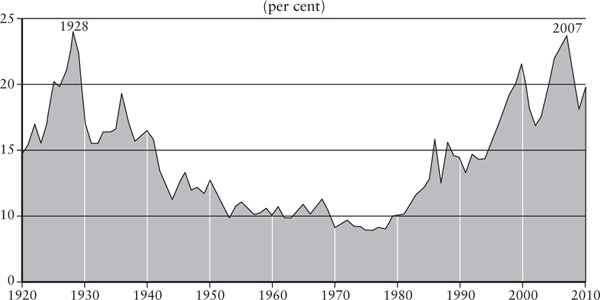

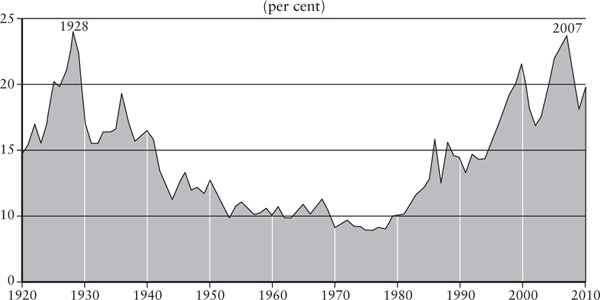

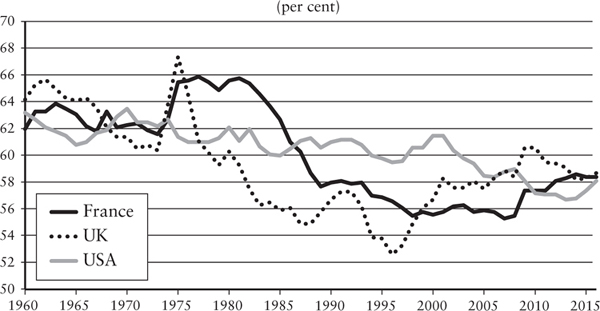

The years leading up to the Great Depression of 1929–32 and the Great Recession of 2008–9 both showed a large increase in share of income going to the rich.

To what extent was disequalization a structural cause of the collapse of 2008–9? The argument is that the more unequal the distribution of wealth and income becomes, the more fragile – dependent on debt finance – will be the spending base of an economy, and therefore the more vulnerable to any collapse of confidence in the financial system. But first let us consider distribution in its microeconomic aspect.

Figure 54. Share of US income going to richest 1%3

The key concept here is Pareto-efficiency. This is a state of optimal equilibrium, in which no one can be made better off without someone being made worse off. Pareto-efficiency is supposed to be the outcome of perfectly competitive markets. But students are also taught that there can be a range of Pareto-efficient allocations – it is Pareto-efficient, for example, for me to have 99 per cent of the income of the economy, because no one else can be made better off without me being made worse off. But there would then be no economy. Otherwise put, Pareto-efficiency leaves open the question of distribution: which distribution to have is a political or ethical judgement.

Economists would readily agree that redistributive policies could improve welfare if one or more of the conditions of a competitive market are not satisfied. For example, owners of monopolies could charge more for their services than they would earn in a competitive market. This would be an argument for taxing their ‘rents’ or breaking up their monopolies. But can redistributive policies be demonstrated to improve total utility even in the absence of such market distortions?

A heroic attempt to demonstrate just this emerged at the start of the last century. The key text was Cambridge economist A. C. Pigou’s Wealth and Welfare.4

His economic agents have identical tastes, but different incomes. Pigou further assumed that the power of an additional pound or dollar to give satisfaction varies inversely to the number of pounds or dollars a person already has, a theorem known as the declining marginal utility of money. A transfer of money from the rich to the poor will thus make the rich slightly worse off, but the poor much better off. The transfer should continue until the marginal utility of money was the same for all. Perfect equality of incomes was unattainable, but the Pigou demonstration pointed the way to a much greater degree of income equalization than would be delivered by even a perfect market. The doctrine of the declining marginal utility of money became the intellectual basis of welfare economics.

This ‘scientific’ argument for redistribution emerged at exactly the same time as politicians were busy setting up the welfare state to stave off the threat of socialism. Marginalist economics seemed to give a scientific underpinning for policies of redistributive taxation and social insurance.

Alas, Pigou’s demonstration failed. Even assuming that people had identical tastes (they all like the same things), the law of diminishing marginal utility of money is impossible to prove, because one cannot compare the marginal utility of money to a rich person with its marginal utility to a poor person in a numerical way. Economists dreamed of developing a hedonometer, described by Francis Edgeworth in 1881 as a ‘psychophysical machine, continually registering the height of pleasure experienced by an individual’.5 The only obvious field of application of such a hedonometer would be in cases of extreme sexual pleasure or fear, unsuitable as criteria for redistributive taxation.

This orthodox critique of Pigou’s effort is too harsh. Granted that interpersonal comparisons of utility are rough and ready, we can and do make them. Obviously £100 means more to a pauper than to a millionaire; we don’t need to be able to say exactly how much more in order to justify some redistribution from one to the other.

But Pigou’s exercise fails to tell us how much redistribution is needed to satisfy his criterion. Attempts to secure an alternative scientific basis foundered. According to the Kaldor–Hicks criterion, a reallocation of income could be Pareto-improving if the winners would gain sufficiently to be able to compensate the losers; for example, if it made the economy grow faster. But the link between distribution and growth is too fragile to provide scientific support for redistributive taxation.

In the absence of a firm number, the hope of deriving an optimum social utility function by these routes faded. Redistribution became a political, or ethical, goal, without a secure theoretical basis in the economics of perfect competition.

Paul Samuelson summed up the position as it appeared in the 1960s:

Under perfect competition, where all prices end up equal to all marginal costs, where all factor-prices end up equal to values of marginal products and all total costs are minimized, where the genuine desires and well-being of individuals are all represented by their marginal utilities as expressed in their dollar voting – then the resulting equilibrium has the efficiency property that ‘you can’t make any one man better off without hurting some other man’.6

Since this situation did not, in fact, hold, the case for greater equality on grounds of social justice or social cohesion was not seriously challenged in the mid-twentieth-century heyday of social democracy. But the lack of a secure economic basis for redistributive taxation was a serious weakness once the political climate shifted against progressive taxation.7

This happened with Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s. Welfare spending entitlements were narrowed. Tax systems were made less progressive to ‘improve the incentives’ of the already rich. In the perfect markets lauded by neo-classical economists, capitalists and workers alike would be paid their economic worth. In this world, there is no rent or unearned income or free lunches. Or, rather, there was only ‘rent-seeking government’.

The theoretical case against redistribution was clinched by the device of the ‘representative agent’. We now have a single consumer who is paid exactly what he produces. The case for redistribution on equity grounds has disappeared. Money still has a diminishing marginal utility, but all this does is to give the representative consumer a choice between income and leisure. A clearer example of economics tracking politics would be difficult to find. By 2004, Robert Lucas could say, ‘of the tendencies which are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on the question of distribution’.8

This position has, in turn, been challenged from outside economics, by Rawlsian political theory, for example.9 More recently, sociologists and psychologists have documented the social and psychological costs of unequal societies. Mainstream economics has been largely indifferent to such considerations.

But what about distribution as a macroeconomic question? Is there a pattern of distribution which will cause economies to be more stable, or grow faster? If so, what is it?

In the Keynesian era of the 1950s and 1960s, full employment policies and policies of greater income equality formed twin pillars of the social democratic consensus, but the dots to link them up were missing. The ‘missing dots’ which make distribution a macro problem are to be found in class differences in the propensity to consume. The rich save more of their incomes than the poor do.

According to the Solow growth model – the simplest in neo-classical economics – the savings ratio should make no difference to long-run output growth so long as the savings are invested. However, in Keynesian theory, market economies have no natural tendency to a full employment level of investment.

This is what gives the distributional question a macro dimension. The higher the saving ratio, the more the investment needed to maintain full employment, but the smaller the consumer market available to absorb the products of the new investment. This dilemma is at the heart of under-consumption theory.

Under-consumption theories – which might just as well be called over-saving theories – have a long lineage, starting in the early nineteenth century and featuring such names as Sismondi, Malthus, Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg.10 Under-consumptionists were impressed by the fact that part of the income generated by production is saved. They then concluded (too hastily) that saving reduces aggregate demand relative to aggregate supply.

Their reasoning went something like this. Imagine an economy that uses money, in which everything produced is consumed, including machinery which wears out at a steady rate. Say’s Law holds: demand equals supply.

But now suppose people decide to invest an extra 10 per cent of their earnings in new machines, rather than just replace old ones. There will then be a simultaneous fall in demand for consumption goods and an increase in capacity to produce them. We have oversaving or over-investment in relation to demand: Say’s Law is breached, a depression ensues.

Orthodox economists pointed out that this chain of reasoning neglects the fact that real incomes rise with the new investment, to enable the purchase of the enlarged flow of consumer goods. No excess stocks of capital accumulate: Say’s Law holds.

The more sophisticated under-consumptionists understood that saving was not a simple subtraction from demand. They were not against saving as such, but against over-saving. Over-saving existed when it led to more investment in new machines than any expected demand for consumables in the future would justify. They thought this could happen when saving was divorced from the desire for more consumption goods, but was an automatic consequence of some people having too much money. The rich have more surplus income than the poor; so the more concentrated wealth became, the more over-saving, and overinvesting, there would be.

By far the most influential under-consumptionist writer was the English liberal thinker J. A. Hobson (1858–1940), who can claim to have influenced both Keynes and Lenin.11 His argument is summarized in his book The Physiology of Industry (1889), which he co-authored with businessman A. F. Mummery:

Saving, while it increases the existing aggregate of Capital, simultaneously reduces the quantity of utilities and conveniences consumed; any undue exercise of this habit must, therefore, cause an accumulation of Capital in excess of that which is required for use, and this excess will exist in the form of general over-production.12

Hobson uses his theory to explain the business cycle. In the boom phase, the saving to income ratio rises, leading to over-saving and the collapse of the boom. As the depression deepens, the saving class reduces its saving to conserve its consumption, and the saving/income ratio falls back to a ‘normal’ rate, before the chronic tendency to over-save starts the whole process again.13

In a subsequent book, Imperialism (1902), Hobson applied his theory to explaining imperialism; imperialism provided a vent for surplus capital and thus a method for overcoming periodic crises of over-production.14 Domestic under-consumption was thus the ‘taproot’ of imperialism. The surplus savings which reduce consumption at home earn an income for capitalists when invested abroad. In a similar vein, the German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg thought that capitalism required external markets, such as afforded by colonies or government spending on armaments, to offset the deficiency of domestic consumption. Lenin’s theory of the inevitability of wars between competing capitalist states, each seeking to export its surplus capital, derives directly from Hobson.15

How does Hobson explain the ‘undue exercise’ of the saving habit? In his books The Problem of the Unemployed (1896) and The Economics of Distribution (1900), he locates it in the class distribution of wealth and income.16

Hobson rejected the marginal productivity theory of rewards to the factors of production. Rather, he generalized Ricardo’s theory of rent to cover the surplus of return over cost which capitalists were able to extract from the workers. This surplus was derived from their ability to monopolize the ‘requisites of production’, i.e. to get ‘rents’ or super-profits from the ownership of scarce factors of production such as land, skills, raw materials and techniques. This put them in a superior bargaining position to labour; in every market the right of the economically stronger prevailed. The more monopolized the ownership of scarce resources, the more opportunities there were to extract rent. The inequalities of wealth thus created were perpetuated and increased by inheritance. Ever alert to the existence of monopoly firms, economists were blind to the existence of monopoly conferred by ownership of the means of production.

The ownership of productive tools by the class of capitalists was at the heart of under-consumption theory. This meant that the fruits of productivity growth went unduly to the saving not the consuming class. Since Hobson assumed that savings were automatically invested, this resulted in periodic gluts of production, which led to periodic slumps. The remedy was to tax ‘surplus’ wealth through a graduated income tax and high death duties, and redistribute it to those with a high propensity to consume. That would end crises of over-production and the need to export surplus capital abroad.17 Hobson attacked low wages as detrimental to both productivity and quality of life, and the high earnings of directors as vastly in excess of their economic contribution.

Hobson thus emphasized class power, but as a contingent rather than a necessary feature of a capitalist system. This was in contrast to Marx, who saw ‘exploitation’ of the worker – paying workers less than they produced – as necessary for profit. For Hobson, only part of profit was rent: for Marx, the whole of it. Marx’s labour theory of value was an attempt to isolate that part of the price of a product which simply provided a free lunch for the owner of capital. Capitalism was driven by the quest for profit, profit derived from exploitation – extracting ‘surplus value’ from workers. But exploitation left workers unable to buy all they had produced. Here was capitalism’s great contradiction: ‘The last cause of all real crises’, Marx wrote, ‘always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses as compared to the tendency of capitalist production to develop the productive forces.’18 His followers regarded social democratic schemes like Hobson’s for redistributing wealth within capitalism as utopian. Exploitation could be ended only by abolishing ‘surplus value’ – extinguishing capitalists as a class.

The Hobson–Marx under-consumption theory of capitalist crisis is at the opposite pole to the Austrian ‘over-consumption’ theory. According to Hayek, it is not over-saving but under-saving that is the problem. The crisis which produces the slump is a crisis of over-investment relative to the amount of consumption people want to postpone, financed by credit-creation by the banking system. The slump is merely the process of eliminating the ‘malinvestments’, those not financed by genuine savings. Slumps can be prevented by stopping banks from creating more credit than people want to save. As the following rap puts it:

You must save to invest, don’t use the printing press

Or a bust will surely follow, an economy depressed.19

The Wicksellian root of this argument is clear.

Keynes was notoriously tone-deaf to Marx, but he was much more sympathetic to Hobson than to Hayek.20 In the General Theory he made handsome amends for his previous neglect of Hobson, enlisting him in the ‘brave army of heretics, who, following their intuitions, have preferred to see the truth obscurely and imperfectly rather than maintain error, reached indeed with clearness and consistency and by easy logic, but on hypotheses inappropriate to the facts’.21 His criticism of Hobson was based on what he saw as a technical mistake in Hobson’s reasoning: it was to suppose that

it is a case of excessive saving causing the actual accumulation of capital in excess of what is required, which is, in fact, a secondary evil which only occurs through mistakes of foresight; whereas the primary evil is a propensity to save in conditions of full employment more than the equivalent of the capital which is required, thus preventing full employment except when there is a mistake of foresight.22

Hobson’s problem, Keynes thought, was that he lacked an ‘independent theory of the rate of interest’.23 He assumed that changes in interest rates automatically equalized private saving and investment, giving rise, on his over-saving theory, to systemic over-investment, interrupted by crises, whereas for Keynes, the rate of interest being the price of money, not saving, the only way of eliminating the ‘excess saving’ at full employment was a fall in national income. Thus Hobson’s was a theory of over-investment: Keynes’s a theory of under-investment.

Keynes thought that the most important remedy for the unemployment of his day was to raise the rate of investment, not reduce it. This would require, in addition to public investment, keeping the longterm rate of interest permanently low, resulting in the ‘euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity value of capital’. For ‘interest today rewards no genuine sacrifice, any more than does the rent of land’.24

Keynes thought that the problem of securing enough investment to match full employment saving would get worse as societies got richer. The propensity to save would rise (the richer people are, the less of their income they consume) while the inducement to invest would fall as capital became more abundant. In this sense he was a long-term under-consumptionist. Once accumulation was no longer a priority, schemes for the ‘higher taxation of large incomes and inheritance’ would come into their own, though Keynes was doubtful about how far or fast they should go.25 He was moderately sympathetic to the ethical case for income distribution, writing that ‘there is social and psychological justification for significant inequalities of income and wealth, but not such large disparities as exist today’.26

Under-consumptionist theory influenced left-wing explanations of the Great Depression of the 1930s, both at the time and subsequently. The explosion of consumer credit kept consumer demand buoyant in the United States up to 1929; its withdrawal amplified the slump. Typical in its under-consumptionist reasoning is this passage from Marriner Eccles, Chairman of the US Fed from 1934 to 1948:

A mass production economy has to be accompanied by mass consumption. Mass consumption in turn implies a distribution of wealth to provide men with buying power. Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929 drawn into a few hands an increasing proportion of currently produced wealth. This served them as capital accumulation. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied to themselves the kind of effective demand for their products that would justify a reinvestment of their capital accumulations in new plants. In consequence, as in a poker game when the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.27

Under-consumption also featured in Marxian explanations of the Great Depression of the 1930s. For example, James Devine argued that, in the US, stagnant wages (relative to labour productivity) meant that increases in working-class consumption could be financed only by debt. Eventually (in 1929), the over-investment boom ended, leaving unused industrial capacity and debt obligations. Once the depression occurred, recovery of private investment and consumption was blocked by falling prices, which increased the real debt burden. Trying to restore the profit rate by cutting wages only reduced prices and consumer demand further. Devine called this the under-consumption trap.28

The modern under-consumptionist story starts with the big increase in inequality, noticeable in all developed countries since the 1970s.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century documented in exhaustive detail the increase in inequality over the last forty years.29 Coming on top of the crash of 2008, it rekindled interest in distributional issues in both their moral and efficiency aspects. Piketty restated the familiar social democratic charge against capitalism: that its ownership system offended the principle of distributive justice. But his analysis also led people, eager to explore causes of the Great Recession of 2008–9 deeper than the familiar tale of predatory bankers, to wonder whether the patchy and unbalanced performance of market economies in recent years was not somehow the result of growing inequality.

The fact that inequality has increased is not in dispute. Median real incomes have stagnated, or fallen, throughout the Western world even as economies have continued to grow. Egregious examples are legion. A frequently cited US statistic is that over the past two decades, the ratio of the pay of CEOs to the average pay of their workforces has increased from 20:1 in 1961 to 231:1 in 2011.30 (For some companies, it is over 1,000:1.) Atkinson, Piketty and Saez show that inequality in the USA fell for decades after the Wall Street crash of 1929 before starting to rise again in the 1970s. Now, the top 1 per cent own over 20 per cent of US wealth. The same pattern is seen in the UK and Italy. This coincides with the transfer of wealth from the public to the private sector. Cross-country studies show that practically all the increase in advanced country wealth in the last twenty years has gone to the top 1 per cent. The rich have raced away from the poor; and the very rich have raced away from the rich.

Edward Luttwak, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, claims that the service economy is in fact becoming a servant economy: ‘toobusy-to-live high-techies employ retinues of nannies, housekeepers, dog walkers, cat-minders, pool boys and personal shoppers’.31 Automation of manufacturing will make more and more servants available to serve the rich.

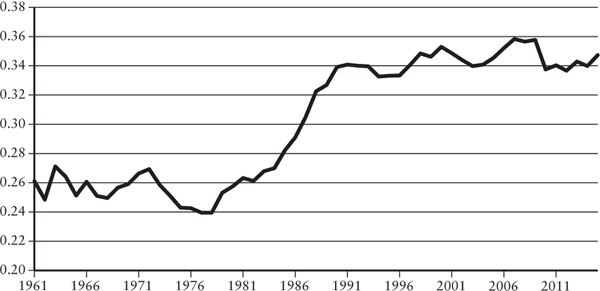

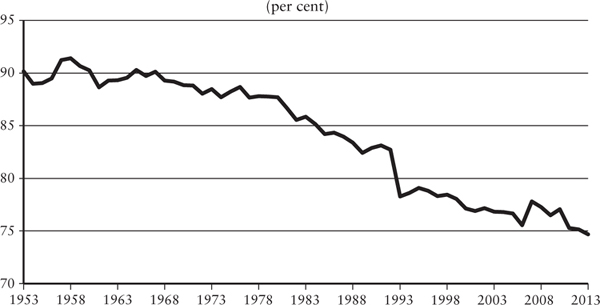

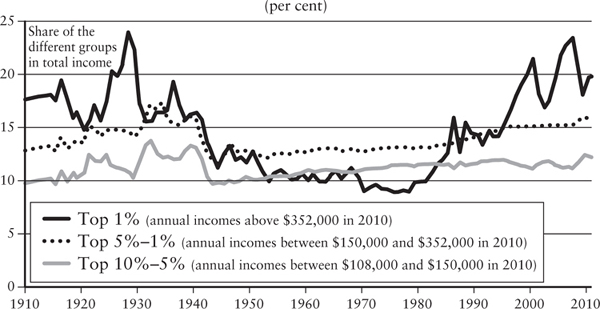

The Gini coefficient for the UK in Figure 55 shows the spurt in inequality from 1979 to 1990. A second chart from the USA (Figure 56) shows the growing gap between mean and median income. (If only the rich are getting richer, mean incomes will rise while median incomes stagnate.)

An important reason for this divergence has been the fall in wage share of national income. Steady at about two-thirds for most of the post-war period, it has fallen to 55 per cent in the last two decades.

Figure 55. UK Gini coefficient32

Figure 56. Median family income as a proportion of mean family income, USA33

The causes of disequalization have been disputed. One of the commonest explanations is the information revolution: the technologically agile have benefitted at the expense of the rest. Another is globalization: cheap labour competition from Asian countries has driven down the median wage of Western workers. A third is the shift in the balance of power from workers to employers. All three might explain widening inequality; only the first might plausibly explain the exorbitant gains of the top 1 per cent.

Figure 57. Labour income share in GDP34

Piketty’s argument is straightforward. The growing concentration of capital in fewer hands, for whatever reason, has enabled its owners to keep it relatively scarce and thus valuable. Urban real estate has taken the place of land as the main source of rent.

Piketty argues that the tendency to increased inequality, inherent in a capitalist system, was suppressed in the period between 1910 and 1960 as the two world wars and the Great Depression destroyed a mass of inherited capital, while trade-union pressure, progressive taxation and welfare prevented its reconstitution. But from the late 1970s, with the decay of these countervailing forces, the natural inequality of the system has reasserted itself, so that today it is almost as great as it was before 1914.35

The historical record so painstakingly dissected can be summarized by what Piketty calls the ‘fundamental force of divergence’, which he represents by the equation r > g. When the return on capital (r) continuously exceeds the growth of the economy (g), inherited wealth continues to grow faster than output and income, meaning that inequality continues to increase, since there is nothing to stop the children of today’s super-salary earners become the rentiers of tomorrow. And the return to low growth, partly caused by ageing populations, means that inequality will rise even more. Piketty predicts that growth will not exceed 1–1.5 per cent in the long-run, whereas the average return on capital will be 4–5 per cent. (This contrasts with the predictions of the American statistician Simon Kuznets, whose data – dating from 1955 – showed inequality naturally diminishing over time.)

Figure 58. Share of US income going to the top36

Using large data sets, Piketty presented a U-shaped curve running from the late nineteenth century to today, with a ‘compression’ of inequality between 1914 and 1970.

It is a sign of the importance of Piketty’s intervention that it provoked a furious debate. This has centred on his use of data and his theoretical framework. Chris Giles of the Financial Times led the empirical assault, asserting that the raw data used by Piketty do not show any increase in the share of wealth going to the top 1 per cent and the top 10 per cent in the UK from 1960 to 2010, rather the reverse.37 His attempt to discredit Piketty failed, but it shows Piketty had hit a raw nerve.38

The second assault, on Piketty’s theoretical framework, was led by left-wing economists who accused him of using a conventional marginal productivity framework to explain the returns to capital. In the words of the American economist Thomas Palley: ‘Mainstream economists will assert the conventional story about the profit rate being technologically determined. However, as Piketty occasionally hints, in reality the profit rate is politically and socially determined by factors influencing the distribution of economic and political power. Growth is also influenced by policy and institutional choices.’39

Similarly, James Galbraith criticized Piketty’s claim that the wage share in national income is technologically determined, leaving governments with scope for intervention only in the post-tax distribution of earnings. Piketty’s mistake had been to treat capital as an independent ‘factor of production’, when a ‘social’ analysis of capital would have shown that its determinants included infrastructure spending, education, regulation, social insurance, globalization and much else.40

Orthodox theorists attribute the build-up of debt, leverage and financial fragility before the crash to ‘misperceptions’ by households, businesses and banks about the sustainable level of lending and borrowing. This is true, of course, but banal. One really wants to know about the source of these misconceptions. Under-consumptionist theory provides one answer: the growth of inequality. Households increase their debt because wages have fallen, but they still wish to consume as much as before. Governments encourage easy credit conditions to offset stagnant real earnings. Banks and firms become ‘over-leveraged’ because they exaggerate the profits they expect to make from consumers’ debt-enlarged incomes. Governments borrow too much because they over-estimate the revenues they will get from over-borrowed financial systems. Thus excessive credit creation, which the Hayekians see as the cause of the financial collapse of 2007–9, can, on further analysis, be rooted in the stagnation or decline of consumption from earnings. ‘Consumption-smoothing’ – consuming expected future wealth today – is the name of the game.

A key argument in this tradition is that a balance between capital and labour existed in the Keynesian era of the 1950s to 1970s; in fact, it was what made Keynesian policy possible. Strong trade unions were able to push wages up in line with productivity; extensive government transfers kept up mass purchasing power. The commitment to full employment created a favourable climate for business investment, and hence improvements in productivity, and the state’s own capital spending policies maintained a steadiness of investment across the cycle. Consumer credit was restricted. As a result, business cycles were dampened, and economies enjoyed unprecedented rates of economic growth.

However, this benign capitalist environment unravelled in the 1970s. First, wage-push by unions led to rising inflation. Attempts by governments to control inflation by prices and incomes policy broke down. With wage inflation pushing ahead of profit inflation, the only solution available under capitalism was to recreate the Marxist ‘reserve army of the unemployed’. This was done through opening up domestic economies to global competition. Higher unemployment simultaneously shifted income from wages to profits and brought down inflation, but at the cost of a secular stagnation.

According to Palley, the collapse of the dotcom bubble in 2001 reflected deep-seated contradictions in the existing process of aggregate demand generation. He saw these as resulting from a deterioration in income distribution. The resulting depressive forces were held at bay for almost two decades by a range of different demand compensation mechanisms: steadily rising consumer debt, a stock market boom, and rising house prices. However, these mechanisms were now exhausted. Fiscal policy would help only temporarily unless measures were taken ‘to rectify the structural imbalances at the root of the current impasse’. Without this, ‘the problem of deficient demand will reassert itself, and the next time around public sector finances may not be in such a favourable position to deal with it’.41

Written in 2001, this was a prescient forecast of the disablement of fiscal policy following the crash of 2008. From 2001 the US housing bubble really began to inflate. The reason is clear enough: the Federal Funds Rate was kept at 1 per cent between 2001 and 2004. So borrowers with no income, no job, no assets, were enticed by very low, almost zero, introductory interest rates on an adjustable-rate mortgage, and this fuelled the growth of sub-prime mortgages. Consequently, the US homeownership rate reached almost 70 per cent in 2004. By 2006, more than a fifth of all new mortgages – some $600 million worth – were sub-prime. And a third of these sub-prime loans were for 100 per cent or more of the home value, and six times the annual earnings of the borrower. In the UK, a large housing bubble was also inflating. By the end of 2007, mortgage debt reached 132 per cent of disposable income, with overall household debt reaching 177 per cent.

In February 2008, just before the US economy collapsed, Palley wrote that ‘the US economy relies upon asset price inflation and rising indebtedness to fuel growth. Therein lies a profound contradiction. On one hand, policy must fuel asset bubbles to keep the economy growing. On the other hand, such bubbles inevitably create financial crises when they eventually implode.’ The need, he said, was to ‘[restore] the link between wages and productivity. That way, wage income, not debt and asset price inflation, can again provide the engine of demand growth.’42

The new under-consumptionism attaches great causal importance to the ‘financialization’ which serves to ‘redistribute income from productive activities to non-productive finance. The rich alone are the winners in that transfer, because it involves no productive activity that might possibly “trickle down” to the rest of us.’43 Financialization is a necessary part of the neo-liberal model, its function being to ‘fuel demand growth by making ever larger amounts of credit easily available . . . The old post-World War II growth model based on rising middle-class incomes has been dismantled, while the new neoliberal growth model has imploded.’44

The argument of this chapter is that distribution is a macroeconomic question, because a distribution of purchasing power heavily skewed towards the owners of capital assets creates a problem of deficient demand. The financialization of the economy increases this instability by allowing debt to replace earnings from work. Quantitative easing increases it still further by creating asset bubbles.

The problem the older generation of under-consumptionists drew attention to was the failure of real wages to keep pace with productivity. But a striking feature of the post-crash years has been the decline in productivity, as workers have moved to less productive jobs. Flexible labour markets, greatly lauded by the conventional wisdom, are bound to slow down productivity growth, because it is more efficient for employers to hire cheap labour than invest in capital, physical or human. This has been a job-rich, productivity-poor, recovery. Moreover, the fall in worker productivity must lead to even greater income inequality, and, therefore (on the under-consumptionist argument), to even greater macroeconomic instability in future, as the economy relies even more heavily on debt.

In Keynesian terms, a situation in which the inducement to invest is falling, but income inequality is rising, is the worst possible basis for both stability and growth. This is the situation in which we find ourselves today.