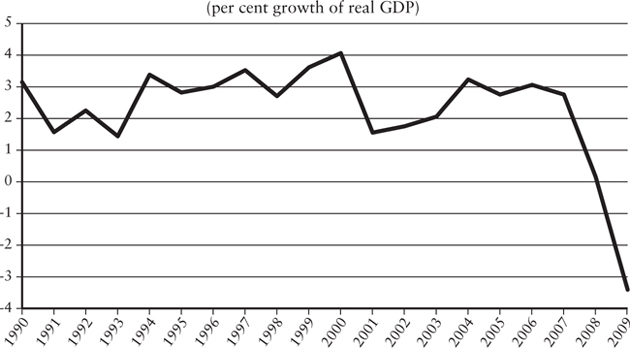

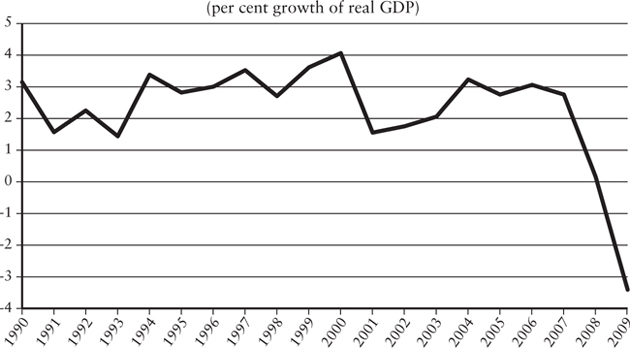

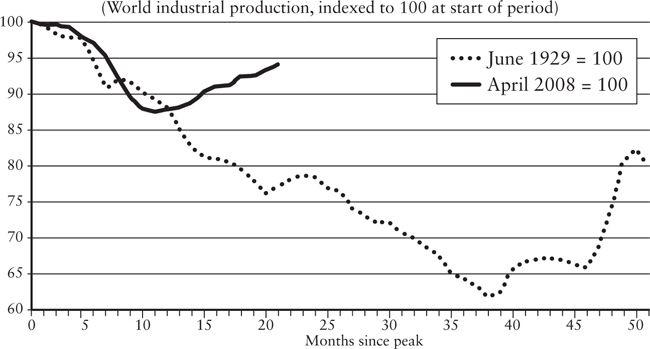

The years running from the early 1990s to 2007 (or, seemingly, from the mid-1980s in the US) are known as the Great Moderation. This was a period of exceptional stability in world economic affairs. Between 1992 and 2007 inflation in the advanced economies averaged 2.3 per cent; economic growth 2.8 per cent.1 Many attributed this success to the creation of independent central banks with a mandate to target inflation. With money at last expected to be ‘kept in order’ by independent central bankers, and governments expected to balance their budgets, the market economy was behaving as most economists said it should. The era of ‘boom and bust’ was over, declared Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown.

Figure 24. Output growth in the advanced economies during the Great Moderation2

Figure 25. CPI inflation in the advanced economies during the Great Moderation3

The euphoria of the pre-crash years was by no one better previsioned than Hyman Minsky:

Success breeds disregard of the possibility of failure. The absence of serious financial difficulties over a substantial period leads to a euphoric economy in which short-term financing of long-term positions becomes the normal way of life. As the previous financial crisis recedes in time, it is quite natural for central bankers, government officials, bankers, businessmen and even economists to believe that a new era has arrived.4

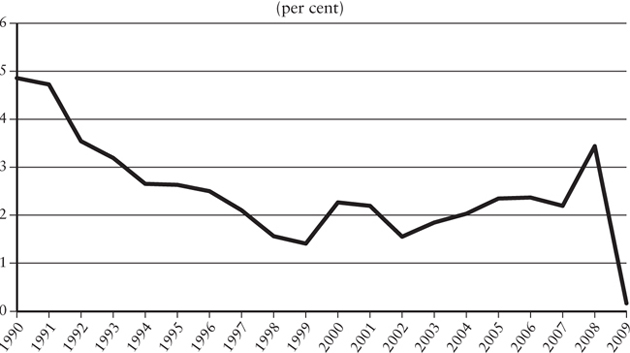

The ‘surprise’ global economic collapse of 2008–9, the worst since the Great Depression of 1929–32, shattered the glass. It forced activist – that is, discretionary – responses from governments that were partly experimental, but that also involved using old tools which had become rusty through neglect. These emergency measures prevented the collapse from becoming another Great Depression. But they failed to produce complete recovery, and they left macroeconomic policy in a mess.

We can identify five distinct stages of the crisis:

1. The collapse of the American sub-prime mortgage market in August 2007. This activated central banks’ role as lenders of last resort.

2. The escalation of the financial crisis with the collapse and rescue of the major US investment bank Bear Stearns in March 2008. The confidence among banks in the quality of each others’ assets deteriorated markedly after this, leading to reduced interbank lending and much greater use of available central bank credit lines. The Fed became a global ‘lender of last resort’, making credit swaps available to fourteen central banks. There was no fiscal response to the first two phases.

3. The collapse and non-rescue of the investment bank Lehman Brothers during the weekend of 13–14 September 2008, which started the third and most acute phase of the financial and economic crisis. A week of total credit paralysis followed, with the payments systems everywhere endangered. Many banks in the USA, UK, Europe and elsewhere went bankrupt and had to be rescued. (Of 101 banks with balance sheets of over $100 billion in 2006, half failed.) Between September and December 2008, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank made available €2 trillion of credit to banks at 1 per cent interest, and started buying government and commercial debt on a small scale. In the fourth quarter of 2008 and first quarter of 2009, GDP in industrial nations fell at an annualized rate of 7–8 per cent. GDP growth slowed down in China and Asia, the main transmitters of the crisis to the developing world being the collapse in their terms of trade (including commodity prices) and paralysis of private capital markets. With an 8 per cent GDP drop, Russia experienced the fastest and steepest collapse in the G20 world.

4. Unlike in 1929–30, the economic collapse produced energetic government responses. Governments strengthened deposit insurance, recapitalized and nationalized banks with public funds, and bought toxic assets. In September 2008 the US government nationalized the insolvent mortgage lenders Fanny Mae and Freddie Mac, transferring their $5 trillion of debt to the taxpayer. US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson announced a $700 billion bailout plan (the Trouble Asset Relief Program) to buy up distressed bank assets; the Icelandic, Benelux and German governments also bailed out parts of their banking systems.5 In October 2008, the G20 committed its members to co-ordinated interest rate cuts and bank recapitalizations. Substantial discretionary fiscal responses included €200 billion from the EU (mainly Germany), $298 billion from Japan, $586 billion from China and $800 billion from the USA. China’s stimulus amounted to 12.7 per cent of its 2008 GDP, the US’s 6 per cent. ‘Cash for clunkers’ was an imaginative early fiscal initiative. The consensus is that the initial response, running from autumn 2008 to spring 2009, stopped the slide into another Great Depression. The ‘green shoots’ of recovery started in the second quarter of 2009. Output fall slowed, risk premia fell, and stock and bond markets recovered. Led by China, Germany and Japan, economic recovery spread to the USA, the UK and the Eurozone in the second half of 2009.

Recovering is not the same as recovery. From medicine we can borrow the idea of an ‘acute’ phase. In the acute phase, all the main ‘health’ indicators are downwards. The collapse then stops and recovery starts. In a serious illness you can take yourself to be fully recovered if you get back to where you were before. In the same way, ‘full health’ can be said to be when the economy recovers its pre-crisis peak. But perhaps you were overdoing it before, which is why you got ill. And the same is true with economies. They may have been growing above trend pre-crash.

Figure 26. Comparing the effects of the 1929 and 2008 crash6

So getting back to their pre-crash peak may be overdoing it again. This would be true of a recovery based on re-igniting the housing bubble.

Speed and strength of recovery varies not just from depression to depression, but from region to region. There can be a period of ‘crawling along the bottom’, or anaemic growth, or very strong (above-trend) recovery. A stylized representation of recovery from 2008–9 would look like this: Asia V-shaped; US U-shaped; Europe a combination of L-shaped (flat-lining) and W (double-dip).

5. Once the corner had been turned, the narrative of the Great Recession changed drastically. The banking crisis turned into a fiscal crisis, and the public debt problem took centre stage. It was at this point that the arguments for austerity began to gain traction. Austerity policies aimed to restore fiscal balances. The restoration of fiscal balance was seen as the necessary condition for recovery of private sector confidence, and hence investment and economic growth. As government tightened the fiscal screws, economic growth fizzled out, coincidentally or not.

Government success in averting another Great Depression has given rise to a piece of mythology: the world economy was saved by the central banks. Typical is the following by Chris Giles of the Financial Times: ‘They saved the global economy from the financial crisis.’7 This is sloppy journalism. It ignores the fact that the proportion of GDP spent by governments was twice as large as in 1929–30, so the automatic stabilizers were much larger. More importantly, it ignores the large discretionary fiscal stimulus in the first six months of the slump. Recapitalizing banks was a fiscal operation, involving governments raising vast sums in the bond markets. It was governments, not central banks, learning from Keynes, not from Milton Friedman, that prevented a slide into another Great Depression, just as it was governments gripped by deficit panic that aborted recovery after 2010.

The communiqué of the September 2009 G20 summit in Pittsburgh read:

Our national commitments to restore growth resulted in the largest and most coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus ever undertaken. We acted together to increase dramatically the resources necessary to stop the crisis from spreading around the world . . . The process of recovery and repair remains incomplete . . . The conditions for a recovery of private demand are not yet fully in place. We cannot rest until the global economy is restored to full health, and hard-working families the world over can find decent jobs . . . We will avoid any premature withdrawal of stimulus. At the same time, we will prepare our exit strategies and, when the time is right, withdraw our extraordinary policy support in a cooperative and coordinated way, maintaining our commitment to fiscal responsibility.8

The G20 communiqués of this period, mainly crafted by Gordon Brown, could have been important milestones in the development of global economic government. However, while Brown was engaged in ‘saving the world’, his domestic political base was crumbling, and in May 2010 he lost the British general election. The next two chapters will tell of the ‘premature withdrawal’ of fiscal stimulus, tasking only a much weaker monetary stimulus with restoring the global economy to ‘full health’.