Rain, Wind and the Wondrous Cold

“Captain Phillip King of HMS Adventure watched the pampero from the shore of Maldonado Bay. Although the day had been hot and sultry, no one had expected the storm that came or the chaos it brought. The Adventure had lain at anchor in the bay with her crew camped on the beach. The day had been set aside for repairs and resupplying stores of water, oranges and meat as King waited for his companion vessel HMS Beagle to arrive from Rio de Janeiro. It was late afternoon on Friday 30 January 1829. The day had passed as usual. Supplies were being ferried across the breakwater. A French frigate, L’Aréthuse, was drifting along the coastline. The sky was ‘gathered and unsettled’. A little after five o’clock King had glanced at his barometer. It had been reading a steady 30” of mercury, but suddenly it had dropped to 29.50. There was a fluttering of the flags. King felt the wind veer. Black clouds were overrunning the sky. All too quickly, the pampero was upon them.1

The winds roared with raw violence. A squall filled the bay. From the shore King saw the Adventure pitched broadside, tugging at its anchors. Tents went scurrying down the beach. One of the Adventure’s boats, fully laden at oar in the bay, was driven up a beach. Another was ‘shaken to atoms’.2 ‘The spray,’ King wrote, ‘was carried up by whirlwinds, threatening complete destruction to everything that opposed them.’ Anxious about his men and the fate of L’Aréthuse, King kept his eyes fixed on the scene before him. He did not glance along the coast to the east. If he had, even for a fleeting second, he might have seen the faint outline of HMS Beagle on the horizon, fighting for her life.

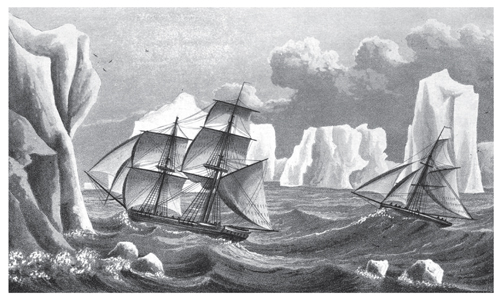

The pampero had hit as the Beagle and her new commander Robert FitzRoy were beating west down Rio de la Plata. They were within sight of Maldonado Bay where FitzRoy had been told to meet King and receive his orders. Until now the long leg from Rio had gone smoothly, the Beagle skimming south along the Atlantic coast under a summer sun. The Beagle was a dextrous bark of just ninety feet, tiny in comparison to the monstrous ships of the line of the Napoleonic Wars. But the Beagle had not been built with fighting in mind. Instead she was flexible: she had the ability to hug shorelines and could be beached for running repairs – advantages that made her ideal for surveying work.

FitzRoy had kept his eye on the weather that afternoon. At 1 p.m. a steady breeze had been blowing from the NNE, an hour later this had freshened, but by 3 p.m. the wind had died away to a near calm. Sailors had an unusual affinity with weather. Knowing how to catch a breeze or to shorten sail was their core skill. A good judge could shave days off a voyage. But that day the weather had been difficult to read. By half past four it was ‘gathered and unsettled’. At 5 p.m. the sky was overcast and FitzRoy noticed thunder and lightning to the south-west. At 5.20 he had trimmed the topgallant sails, jib and spanker, and hoisted the mainsail in their place. There was something else too. Like King, FitzRoy noticed that his barometer had dipped. In the last half-hour it had fallen: 29.90, 29,80, 29.60. It meant only one thing. But before FitzRoy could act, just after 5.40 p.m., a ‘tremendous and sudden squall’ struck the ship.3

The crew, midway through hoisting the mainsail, had it ripped out of their hands. The lines and yards were carried overboard, as was a boy called Thomas Anderson, blown into the waters from thirty feet. Suddenly the Beagle’s prow was twisting in the sea, waves crashing into her bows. For a dramatic few minutes all was confusion. It was a pampero. Everyone on board had heard of these viciously powerful south-westerly gales that rose with mounting force over the Argentine Pampas and exploded across La Plata. They could whip up a terrifying squall in minutes. Brief, ferocious, deadly, they were the meteorological equivalent of a piranha attack.

FitzRoy saw lightning, rain and hail almost at once. The fragile bark, one of a class ridiculed as coffin brigs by naval men, was helpless in the face of the assault. Her topmasts and jib boom were sheared off along with a handful of spars. At one terrifying moment she was pitched back on her beam ends in the rolling sea within a few degrees of capsizing. It was only when FitzRoy cut away the best bower and small bower anchors that she was brought to the wind and righted. By 6 p.m., just fifteen minutes after the pampero hit, the worst had passed – but not before a second seaman, Charles Rosenberg, had been lost overboard.

This incident, on his very first cruise as a commander, would haunt FitzRoy. Charged with a ship and the lives of its crew he had come within a whisker of being wrecked within six weeks of his appointment. Thirty years later he retained a vivid picture of the scene; and of the ‘two fine fellows’ who were blown from aloft. ‘[They] swam hard for their lives,’4 FitzRoy recalled, ‘but were immediately overwhelmed by the sea.’ Had he struck sail earlier, perhaps the crew would have been sheltered on deck. In the age of sail a commander might make a hundred decisions a day: tacking, turning, reefing, furling, sending down yards, leading drills. Each order was important, and in bad seas the margins between speed, safety and disaster were perilously thin.

It was a reality FitzRoy understood. Commanders were selected for their character: they were men of judgement who acted with conviction. FitzRoy himself would later write,

Those who never run any risk; who only sail when the wind is fair; who heave to when approaching land, though perhaps a day’s sail distant; and who even delay the performance of urgent duties until they can be done easily and quite safely; are, doubtless, extremely prudent persons: but rather unlike those officers whose names will never be forgotten while England has a navy.5

But FitzRoy felt the responsibility. He particularly dwelt on his failure to heed the barometer. ‘Signs in the sky, barometric evidence, and temperatures shewed what was coming,’ he would remember, ‘but want of faith of such indications, and the impatience of a very young commander in sight of his admiral’s flagship induced disregard, and too late an attempt to shorten sail sufficiently.’6

Two days later, on 1 February, the battered and broken Beagle was finally able to join King and the Adventure in Maldonado, where she underwent repairs. Nothing else is said of FitzRoy’s misjudgement. A pampero was the kind of misfortune that could befall a commander in the southern oceans. The loss of the two sailors was considered one of the perils of the sometimes brutal, sometimes serene, life at sea.

* * *

Aristocratic, dashing to the eye and fiercely capable, FitzRoy was among the Navy’s finest young hopes. He was born on 5 July 1805 into a family with impeccable Tory credentials. His father, Lord Charles, was an army general and later the MP for Bury St Edmunds. His mother Lady Frances Stewart was the half-sister of the statesman Lord Castlereagh. His grandfather, the Duke of Grafton, had served as prime minister and through his paternal blood FitzRoy could trace his lineage right back to King Charles II. It was a pedigree few could match. Although FitzRoy’s mother died when he was five his childhood was seemingly a happy one, spent at the family’s fine Palladian mansion in Northamptonshire. From their Midland base the FitzRoys maintained links to society life in London and the shires. During Robert’s childhood Castlereagh had been advancing through the political ranks and, best of all, twice in the Regency years the family scooped the ultimate social prize when their horses, Whalebone and then Whisker, romped home at the Derby.

But it was the sea and not politics or society that had caught FitzRoy’s imagination. One of the few surviving stories of his early years is a playful account of his maiden voyage. It took place on a large pond at his family’s estate. Always one to seize an opportunity, FitzRoy commandeered a laundry tub from the kitchen during the servants’ dinner hour. He hauled the tub to the pond, loaded it with bricks for ballast, and launched his craft. Like a Cook or Bligh in miniature FitzRoy progressed valiantly from one side to the other, propelled by a long pole. Reaching his destination he ruined his triumph by overbalancing, capsizing and tumbling right in. Soaked through, he was fished out by the gardener.7

FitzRoy’s naval career recovered from this inauspicious beginning. After brief stretches at Rottingdean and Harrow he rounded off his education at the Royal Naval College in Portsmouth. Here he blossomed. He swept through the three-year course, a heady mix of classics, mathematics, Newtonian philosophy, navigation, languages, fencing, dancing, painting, gunnery and drawing, and emerged the star pupil. Within a year and a half he was serving his midshipman apprenticeship on the oceans of the world. It was a practical education and served him well.

After five years he returned to Portsmouth, by now a hardy tar, to sit his lieutenant’s examination – a notorious test of skill and a frightful ordeal. FitzRoy was forced to stand before a panel chaired by Sir William Hoste – veteran of the Napoleonic Wars – and suffer hours of close questioning. It was an intellectual Battle of Trafalgar, nautical scenarios lobbed from all angles like missiles. ‘All the questions were worked correctly,’8 FitzRoy wrote. ‘Many of them by three methods (one being by algebra and spherical trigonometry) – the other two practical ways, suitable to quick or to rigorous calculation.’ Out of twenty-six entrants, FitzRoy came first. He left the college with an unprecedented double of full marks and the Gold Medal.

FitzRoy’s education did not end there. On being gazetted a lieutenant he stocked his cabin with an incredible 400 volumes, outdoing even Beaufort. The books fed a mind that was more disciplined than brilliant. His success was grounded in determination and hard work more than raw talent. While at sea he found time to study Latin, Greek, French, Italian and Spanish. He kept pace with the latest scientific news, and developed a particular relish for phrenology, the fashionable subject of the day. An odd, boisterous science, phrenology sought to expose links between the size and shape of the human head and the character of the individual. It burned brightly for some years because it fed into the contemporary mania for categorising everything from animals to plants to clouds. One of phrenology’s loudest British champions was Thomas Forster, who was credited with coining the word. FitzRoy subscribed to the idea completely; it was just the subject to appeal to a young mind bent on order.

In contrast to frivolous novels and dusty philosophical books by men like Burke and Gilpin, science was considered wholesome and pure: a proper pursuit for those of refined tastes. In the 1820s one of the great ways to dazzle the opposite sex was to talk of the stars or the planets. Science offered a way of making sense of an over-complex and cluttered world, and phrenology promised to bring order to the most complicated subject of all: the human mind. FitzRoy followed a simple mental checklist – the head and temple, nose and chin – to diagnose the personality of the person before him. Were they bold or timid? Clever or stupid? Lazy or fizzing with life?

Phrenology fuelled the outlook of a man who was already climbing the professional ladder with noticeable speed. Most in the Navy had already heard of FitzRoy, the handsome aristocrat with the fierce work ethic and brooding temper. The Admiralty liked what they saw. His intellectual prowess and aristocratic heritage was a potent mix. Some speculated that he had a fortune of £20,000. He was marked down as cool-headed, shrewd, undaunted, true: equal to the challenge ahead.

* * *

Captain King had established Maldonado Bay as the fair-weather launch pad for the Admiralty’s survey of the southern end of the South American continent. Since 1826 the Adventure and Beagle had navigated the wild Patagonian coasts and channels, adding detail to the few threadbare charts that existed. They sought to map an area that mirrored the Scottish coast in its geography, sweeping in shallow coves on the east, and fractured and splintered into thousands of tiny islands on the west. One hundred and sixty miles from the southernmost point of the continent, the survey had stretched through the fabled Strait of Magellan, a jagged vein of water that cleaved the Atlantic and Pacific, offering merchants bound for Tahiti, the Sandwich Islands, New South Wales or Van Diemen’s Land an alternative route to the infamous Cape Horn. Between Strait and Cape they had explored the outer fringes of Tierra del Fuego, a mountainous, inhospitable archipelago thinly populated with guanacos, foxes, condors, kingfishers, pumas and primitive Fuegian tribes.

The South American survey had been commissioned by Viscount Melville, Lord of the Admiralty, in 1825. It was part of an invigorated naval policy that included Arctic exploration and fresh attempts to locate the North-West Passage. Newly free from a generation of war, the Admiralty had decided to turn Britain’s naval mastery and surplus of ships to different ends. Still poorly charted, South America had a powerful allure. Though Britain’s possessions in the region were restricted to the Falkland Islands, the government had plans to extend its interests. As a Christian nation that thought itself uniquely blessed by God, it was Britain’s duty to civilise the continent and to liberate its untapped mineral deposits.

In the 1760s John Byron, or ‘Foul Weather Jack’, had returned from Tierra del Fuego with enticing tales of a landscape filled with ‘the finest trees I ever saw’. ‘I make no doubt,’ he wrote, ‘but they would supply the British Navy with the finest masts in the world.’ Byron described a wild world with unbounded forests, white with snow, ripe with potential, enriching his account with tales of ‘innumerable parrots and other birds of the most beautiful plumage’.9 Byron included an extra titillation for the Georgian aristocracy, notorious for their love of blood sports: the land was teeming with potential quarry. ‘I shot, every day geese and ducks enough to serve my own table,’ he declared, ‘and several others, and everybody on board might have done the same.’10

Fifty years would pass before the Admiralty had the chance to test Byron’s tales, and their enterprise was hurried along in the post-Waterloo world by two audacious voyages. The first was made by William Smith of Bligh in Northumberland who stumbled upon an outcrop of islands in the Southern Ocean, which he christened the South Shetland Islands and claimed for Britain. News of Smith’s discovery caused a ripple of excitement in Europe. If navigators as able as Cook and Bligh had overlooked an entire cluster of islands, then what other treasures might exist?11 This prospect was reinforced by the news that Smith’s discovery had sparked a craze in seal hunting. In the two years that followed, 100,000 seals were slaughtered on the South Shetlands for their fur or blubber.12 Twenty thousand tons of sea-elephant oil were harvested for the London market by two hundred seamen who were employed by the trade. But, irritatingly for the British, it was the American merchants who made the greatest profit. Quicker to the prize, the Americans loaded ships full of sealskins and transported them across the Indian Ocean to the Chinese market where they were sold for five dollars each. Fortunes were made in a single crossing.

One lured to the southern seas was a British sailor, James Weddell, in his brig Jane. Accompanied by a fellow seaman Matthew Brisbane in a cutter called Beaufoy, Weddell embarked in 1822 on one of the most unlikely voyages of the century. Finding the seal grounds exhausted in the South Shetlands, Weddell continued southwards. He sailed into a dark and inhospitable world of freezing fog and biting winds, dodging through a jigsaw of icebergs. Incredibly, Weddell travelled to within a day or two of the then unknown Antarctic continent, further south than anyone in recorded history. Like Coleridge’s ancient mariner Weddell had entered a world of glimmering ice and wondrous light, a place that Ishmael in Moby-Dick would dub that ‘charmed circle of everlasting December’.13 On 20 February 1823 he stopped at a latitude of 74º15’ S. Surrounded by a thickening, shifting seascape Weddell ordered three cheers, the hoisting of the Union Jack and for the cannon to be fired.14

Once home, Weddell published A Voyage Towards the South Pole, Performed in the Years 1822–1824. It was filled with descriptions of humpback whales, sea leopards, condors and gigantic albatrosses. On South Georgia Weddell had been charmed by the sight of crowds of penguins looking, at a distance, like ‘little children standing up in white aprons’.15 Weddell’s playful descriptions and quixotic ability to extract himself from perilous situations made a winning formula and his account was published in 1825 to enormous success. Having disproved the existence of South Iceland and written up a set of weather guidelines for sailing around Cape Horn, Weddell’s final flourish was to dedicate his book to Viscount Melville. His voyage sent a message right to the heart of government.

* * *

In 1829 FitzRoy was co-opted on to the South American Survey as the new commander of the Beagle. On 27 March, repairs having been completed, he received his orders from King. He was to chart an unexplored stretch of the Strait of Magellan that included a series of bays: Lyell Bay, Cascade Bay, San Pedro Bay and Freshwater Bay. After this he was to navigate the labyrinth of sinuous passages to the west of the Strait. This was a zone poorly known, barely charted and filled with fast tides, hidden currents and concealed rocky outcrops, any of which could send the Beagle to the bottom in a minute. She was to roam this world alone during the winter months. For FitzRoy, who had trained half his life for the opportunity, it was to be a baptism of fire. By 19 April 1829 the Beagle had ghosted through the narrow entrance to the Strait and taken on provisions at Port Famine. That day she parted from her companion schooner, Adelaide, and began her cruise.

FitzRoy was instantly charmed by the landscape around him: the leaden rocks and beech trees on the shore, the silvery hue of the water, the intensity of the light. Glaciers tumbled down the mountainsides, their transparent blue contrasting strikingly with the snow on the mountaintops.16 ‘I cannot help here remarking,’ he wrote in his journal, ‘that the scenery this day appeared magnificent.’ In the distance he saw the outline of Mount Sarmiento, a pyramid of ice and snow, a blend of Ancient Egypt and the Arctic. He noticed the ‘continual change occurring in the views of the land, as clouds passed over the sun, with such a variety of tints of every colour, from that of the dazzling snow to the deep darkness of the still water’.17

The feeling of exhilaration stayed with FitzRoy. ‘The night was one of the most beautiful I have ever seen,’ he recalled. Only the gentle lullaby of the water on the timbers, the creaking of the hull, the knock of the anchor chain and the ringing of the ship’s bell disturbed the silence. It was ‘nearly calm, the sky clear of clouds, excepting a few large white masses, which at times passed over the bright full moon’. Moonlight shone on the rugged snow-covered peaks of the surrounding mountains that ‘contrasted strongly with their dark gloomy bases, and gave an effect to the scene which I shall never forget’.18

Onshore at Cascade Bay the crew discovered limpets and mussels ‘of particularly good quality’ to augment their stores of wild celery and cranberries. As April wore on, despite several squalls of snow, FitzRoy found the temperature better than expected, never dropping below 31°F. With members of the Beagle’s crew he made daily sallies to shore to botanise in the bays, take measurements and collect specimens. The crew shot wildfowl when they could and, best of all, a black swan, which was kept for a special occasion. FitzRoy revelled in the solitude. ‘Though the season was so far advanced,’ he wrote in early May, ‘some shrubs were in flower, particularly one, which is very like a jessamine and has a sweet smell. Cranberries and berberis-berries were plentiful: I should have liked to pass some days at this place, it was so very pretty; the whole shore was like a shrubbery.’19

On 7 May, FitzRoy took a group of men in the Beagle’s whaleboat and cutter and set out to explore a little-known waterway called the Jerome Channel. They took enough provisions with them for a month’s surveying. FitzRoy captained the whaleboat, an open-topped vessel used under oars that was pointed at both ends to allow it to beach, and they glided through the cold, twisting waters ‘with all the anxiety that one feels about a place, of which nothing is known, and much is imagined’. In midwinter at the edge of the known world, this was ultimate freedom. FitzRoy bathed in the shallow waters, stopping to measure the temperature (42°F).20 He and his men scrambled up a nearby hill, called the Sugar Loaf, carrying barometers, theodolites and telescopes. ‘It cost a struggle to get to the top with the instruments,’ he admitted, ‘but the view repaid me.’ At the summit a swathe of Tierra del Fuego opened up before them. Far away from Croghan Hill in Ireland, FitzRoy experienced the same thrill of adventure as Beaufort had a quarter of a century before.21

It was now mid-May and FitzRoy was working in the depths of a South American winter. With the beauty came danger. The days were shortening. The sun did not rise above the hills till about eleven o’clock and it disappeared again shortly after two. The weather, too, was about to change. On the 17th ‘a heavy squall of wind and hail passed over from the south west, so cuttingly cold’, FitzRoy wrote, ‘that it showed me one reason why these plains, swept by every wind from S.S.W. to N., are destitute of trees.’ The next night it was again very cold. Rain fell heavily and a hard gale blew up from the south-west. At night on 19 May the skies were so clear that FitzRoy was able to gaze into the glittering heavens and he woke to a blue dawn. ‘Everything was frozen.’ The whaleboat was useless until its sails were thawed. Just after midday, FitzRoy ordered it to be rowed out in search of a channel between Otway Water and the Strait of Magellan. It was a fateful decision.

The breeze was already stiff and for two hours they pulled against a rising swell. FitzRoy had no choice but to continue. On either side the shore was unbroken, flat and low, with a great surf breaking against it. ‘To have attempted to land, would have been folly.’ A further hour passed. The whaleboat was now taking on water: the crew’s bags and clothes were saturated. As the sun set at four o’clock the wind was as strong as ever. In the cold darkness, all dangers were multiplied. FitzRoy continued:

Night, and having hung on our oars five hours, made me think of beaching the boat to save the men; for in a sea so short and breaking, it was not likely she would live much longer. At any time in the afternoon, momentary neglect, allowing a wave to take her improperly, would have swamped us; and after dark it was worse. Shortly after bearing up, a heavy sea broke over my back, and half filled the boat: we were bailing away, expecting its successor, and had little thoughts of the boat living, when – quite suddenly – the sea fell, and soon after the wind became moderate. So extraordinary was the change, that the men, by one impulse, lay on their oars, and looked about to see what had happened. Probably we had passed the place where a tide was setting against the wind. I immediately put the boat’s head towards the cove we left in the morning, and with thankful gladness the men pulled fast ahead.22

FitzRoy was not a man given to melodrama. His account conveys the vulnerability of their situation. That the whaleboat survived this encounter with the weather must be put down to fine seamanship, colossal effort and phenomenal luck. But it came as a warning. For days FitzRoy had been scribbling meteorological notes in his journal, recording his surprise at the ‘mildness of the weather’. Now, in the space of a few hours, he had seen how swiftly conditions could change. If the Strait had a beauty, it was a restless, dangerous beauty. In minutes a blue sky could be overrun by powerful winds and squalls, thunder and dark clouds. The dilemma for commanders like FitzRoy was not if the weather would turn, it was when.

Any navigator who sailed through the narrows at the western opening of the Strait of Magellan was willingly entering this world. To pass them was to cross the Rubicon, and a test of physical and mental ability awaited. The silver river, the blue sky, the gentle breeze from the west, the liquid calm – all these could lull a navigator into complacency. And the speed with which the atmosphere could change was frightening. At midwinter FitzRoy would first encounter a williwaw, a burst of mountain wind that King had experienced a year before. To King these were ‘hurricane squalls’ that ‘rush violently over the precipices, expand, as it were, and descending perpendicularly, destroy everything movable’.23 Williwaws were a notorious trademark of Tierra del Fuego and, in particular, the Strait of Magellan where winds were tunnelled towards the river by the surrounding mountains. Less energetic than a pampero, a williwaw still had the potential to inflict great damage. King described how ‘the surface of the water, when struck by these gusts, is so agitated, as to be covered with foam, which is taken up by them, and flies before their fury before dispersed in vapour’.24

Increasingly fascinated by the weather, FitzRoy started to analyse it with closer attention in his journal. On 18 May he wrote, ‘For the last four nights I noticed, that soon after sunset the sky was suddenly overcast, a trifling shower fell, and afterwards the heavens became beautifully clear.’25 Ten days later, he returned to this theme. ‘Almost every night I observed that the wind subsided soon after sunset, the clouds passed away, and the first part of the night was very fine; but that towards morning, wind and clouds generally succeeded.’ Here is FitzRoy at the start of his interest with weather. He emerges as half scientific observer and half weather-wise sailor, looking to expose telling patterns or templates for future reference.

At the end of May six weeks had passed since FitzRoy embarked on his orders. In his own manner he had established himself as a leader. After the whaleboat incident on 20 May he had noted, ‘No men could have behaved better than the boat’s crew: not a word was uttered by one of them; nor did an oar flag at any time, although they acknowledged, after landing, that they never expected to see the shore again.’ Such an account can only have been left by a man with a natural ability to lead. FitzRoy had his own distinct charisma. He didn’t inspire with bravado or buccaneering showmanship; he led by example. The men respected his ability, hard work and even-handedness. As the onshore explorations continued, he abandoned the comforts and privacy of his own tent and slept in the open with ‘two or three of the men’. He noted in his journal, with an uplifting flourish, ‘My cloak has been frozen hard over me every morning; Yet I have never slept so soundly, nor was in better health.’26

* * *

In this vast and distant wilderness the Beagle and her boats were tiny cells of scientific endeavour. Along with her anchors and cables, hawsers and kedges, she carried a full complement of philosophical instruments that allowed FitzRoy to continue with his endless round of measurements: sextants, quadrants and compasses for navigation, theodolites for triangulation, levels, gauges and balances for soundings and chronometers for calculating longitude. Onboard the Beagle were also a variety of meteorological tools: thermometers, hygrometers, a pluviometer for measuring rainfall, several different barometers and a sympiesometer, a lightweight and portable mercury-free barometer that FitzRoy favoured above all.

FitzRoy’s education and instinct told him to quantify everything he discovered. The depth of a channel, the incline of a bank, the bearings of a point, the height of a hill, the temperature of the air, its humidity and pressure. Science outdoors had been made fashionable over the previous fifty years by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who had taken meteorological readings in the Alps, and the Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt, whose scientific exploits in Europe and Latin America, to FitzRoy’s generation, were the stuff of legend. Now FitzRoy was taking up the mantle. Bartholomew Sulivan, one of his officers, observed FitzRoy’s diligence. In his autobiography he later stated, ‘[FitzRoy] was one of the best practical seamen in the service, and possessed besides a fondness for every kind of observation useful in navigating a ship.’27 Traces of his commitment to detail are evident in the Beagle’s log. Shortly after the pampero on 30 January FitzRoy made alterations to the standard tables. Unusually for a commander, he had always kept daily readings of the pressure and temperature, but after Friday 20 February, ‘a squally day’,28 he started to take barometric readings every three hours.

Weather records were an important part of FitzRoy’s daily observations. By the 1820s the meteorological tools – the thermometer, the barometer and hygrometer – were well established. But they still retained a fashionable allure: their strange alchemy distilled nature, stripping it down to its numerical core. Frosty mornings, clear nights and stormy afternoons were not just to be recalled by adjectives and metaphors. Far better was to describe the atmosphere with a series of numbers.

The thermometer was the most trusted instrument. In Britain, Fahrenheit’s thermometers had already been in use for about a century. They were renowned for their accuracy and were used at sea to take daily measurements of the water and air. After Franklin’s mapping of the Gulf Stream in 1770 thermometers were used to test whether a vessel was labouring to New York against the famous warm current – ‘the River in the Ocean’ – a small detail that could cost a ship two weeks at sea. The hygrometer was similarly prevalent, a device that enabled measurement of the levels of moisture in the air.

There were innovations too. In 1823 John Frederic Daniell, an experimental philosopher and businessman in London, had grown so fed up with the quality of hygrometers that he had developed a new model. The result was the Daniell Hygrometer. The improved instrument helped to predict frosts, dews and precipitation with accuracy. This hygrometer remained in use for decades and would be celebrated as a ‘perfect and elegant instrument’. The Beagle and Adventure carried some of the first Daniell Hygrometers ever used outside Britain. On the Adventure readings were taken at 3 p.m. daily and entered into a meteorological journal.29

The barometer, though, was the most intriguing instrument of all. In his Ample Instructions for the Barometer and Thermometer (1825), Jeffery Dennis wrote, ‘The barometer is probably the most useful, entertaining and interesting of all philosophical instruments.’ It allowed him to ascertain the weight of the atmosphere, ‘heights of the mountains, and the depths of caverns and mines’.30 It performed a single, simple task: reading atmospheric pressure. But from this measurement a thousand possibilities sprang. Like no instrument before, it seemed to predict coming weather conditions. A plunging reading, like that FitzRoy noticed off Maldonado Bay in 1829, often presaged wind and rain. Equally, a high, settled measure would imply a spell of fine weather.

In the century and a half since Robert Boyle had introduced the barometer into England, no universal laws of prediction had been concluded from it. As a device it could be fickle and untrustworthy. Centuries of analysis had been ploughed into breaking the barometer’s enigmatic code, all to no avail. Driven mad by the complexities John Frederic Daniell lamented in his Meteorological Essays (1823) that some had even gone so far as to abandon Newton’s laws of physics in their desperation to solve the riddle. Daniell laughed at one of the latest theories: that the powerful force of a horizontal wind disturbed the downward force of air pressure – knocking it off its feet like an old man on a windy pier.

Spotting an opportunity, some barometer manufacturers had begun supplying instruments with lists of hints for the user: code books that helped decode atmospheric signs. Like a forerunner of the twentieth-century instruction manual these books encouraged the user to tabulate a set of signals with their specific geographic position. Dennis’ book included a detailed section on using barometers at sea:

In winter, spring and autumn, the sudden falling of the mercury, say 3-10ths of an inch, always denotes high winds and storms, but in summer it presages heavy showers and thunder; it invariably sinks lowest of all when great winds prevail, though not accompanied with rain: it always falls more for wind and rain combined than either of them separately. Also, if after strong winds and rain together, the winds should change in any part of the northern or southern hemisphere, accompanied with a clear and dry sky, and the mercury rise at the same time, it is a certain indication of fine weather.31

Taking accurate measurements was a vital part of being a good sailor. For all his courage and success Weddell was criticised for his slapdash approach to record-keeping. Ten days before reaching the southernmost point of his Antarctic odyssey he broke his thermometer and, having no replacement, gave up on his measurements, a fact he later regretted: ‘I was well aware that the making of scientific observations in this unfrequented part of the globe was a very desirable object, and consequently the more lamented my not being well supplied with the instruments with which ships fitted out for discovery are generally provided.’32 It was an important point. Voyages could cost thousands of pounds and often involved years of work. The loss of data in a shipwreck was a constant fear. While wintering at the Falkland Islands in 1823 Weddell had met the French scientific adventurer Commodore Freycinet whose ship had been wrecked on a submerged rock in the bay. Freycinet was returning home after a ‘voyage of science almost round the world, and after having spent nearly three years’. Though Freycinet managed to save his men and most of his papers and specimens, the disaster was a warning for others.

There were other signs of nature that were worth studying. In 1827 Thomas Forster published a Pocket Encyclopaedia crammed with natural weather signs. According to Forster, rain was foreshadowed by aches and pains in the human body, or toothache; ants bustling over their anthills carrying eggs; asses braying in the fields, cattle gambolling and candles flaring. Fine weather was coming when larks flew high. Thunderstorms were presaged by milk suddenly turning sour. An east wind gave the nervous ‘headaches and hurrying dreams’, while, most vividly of all, Forster pointed out, ‘when there is a piece of blue sky seen in a rainy day big enough, as the proverb says, “to make a Dutchman a pair of breeches”, we shall probably have a fine afternoon’.33

Too late to make Forster’s selection was another sprightly fact, reported in 1829 in the Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature and Art:

At Schwitzengen, in the post house, we witnessed for the first time what we have since seen frequently, an amusing application of zoological knowledge, for the purpose of prognosticating the weather. Two frogs, of the species Rana arborea, are kept in a glass jar about eighteen inches in height, and six inches in diameter, with the depth of three or four inches of water at the bottom, and a small ladder reaching to the top of the jar. On the approach of dry weather the frogs mount the ladder, but when wet weather is expected, they descend into the water. These animals are of a bright green, and in their wild state, here climb the trees in search of insects, and make a peculiar singing noise before rain.34

Amusing to some, to others it was an embarrassment that a frog in a jar or a Herefordshire bull in a farmer’s field knew a storm was coming before the urbane men of science in a townhouse, with their instruments at the ready. This was not the only provocative fact. De Saussure wrote that ‘it is humiliating to those who have been much occupied in cultivating the Science of Meteorology, to see an agriculturist or a waterman, who has neither instruments nor theory, foretell the future changes of the weather many days before they happen, with a precision, which the Philosopher, aided by all the resources of Science, would be unable to attain.’35

As if to confirm the enduring attraction of weather-wisdom, in 1827 Hurst and Chance, a London publisher, had released a new edition of an old book with a tumbling title, John Claridge’s The Shepherd of Banbury’s Rules – to judge the Changes of the Weather, Grounded on Forty Years’ Experience; By which you may know The Weather for several Days to come, and in some Cases for Months. First published in 1670 for two centuries the book had been a popular reference work for weather prognostication. In the 1740s an artful introduction had been added, supposedly by a man called John Campbell, that sought to justify its place alongside scientific treatises.

The Shepherd whose sole Business it is to observe what has a Reference to the Flock under his Care, who spends all his Days and many of his Nights in the open Air, and under the wide spread Canopy of Heaven, is in a Manner obliged to take particular Notice of the Alterations of the Weather, and when once he comes to take a Pleasure in making such Observations, it is amazing how great a Progress he makes in them, and to how great a Certainty at last he arrives by mere dint of comparing Signs and Events, and correcting one Remark by another. Every thing in Time becomes to him a Sort of Weather-Gage. The Sun, the Moon, the Stars, the Clouds, the Winds, the Mists, the Trees, the Flowers, the Herbs, and almost every Animal with which he is acquainted. All these I say become to such a person Instruments of real Knowledge.36

This knowledge was presented in about thirty weather maxims of different layers of complexity, all derived from years of experience out in the Oxfordshire pastures.

If the Sun rise red and fiery – Wind and Rain

Clouds like Rocks and Towers – Great Showers

Clouds Small and round, like a Dapple-grey, with a North-Wind – Fair Weather for 2 or 3 Days

Mists. If they rise in low Ground and soon vanish – Fair Weather

Campbell argued that it was wrong to create a division between scientific research and the wisdom of shepherds like Claridge. ‘Men who derive their knowledge entirely from Experience are apt to despise what they call Book Learning, and Men of great Reading are apt to fall into a less excusable mistake, that of taking the Knowledge of Words for the Knowledge of Things.’ It was a fair point and one that crystallises the contrasting figures of the philosopher in his study and the watcher – the sailor, the shepherd, the ploughman – observing the world at first hand. On HMS Beagle, FitzRoy was a mixture of these archetypes. He had learnt at Rottingdean, Harrow and Portsmouth and he had studied on the world’s wildest oceans. He was a philosopher but at the same time he was weather wise, with the skill to draw conclusions from the world around him.

* * *

By July FitzRoy had completed his survey of the Strait. He sailed west into the Pacific and then to the north up the craggy South American coastline to rendezvous with Captain King at San Carlos on the island of Chiloé. At Chiloé the Beagle was refitted and replenished and a replacement boat was built.

FitzRoy received instructions from King on 18 November 1829. He was told to chart the southern coastline of Tierra del Fuego, starting at the western opening of the Strait of Magellan, skirting the bottom of South America, rounding Cape Horn, and returning up the eastern coast to Montevideo. King told FitzRoy he planned to be in Rio on 1 June the following year. Until then, for almost seven months, FitzRoy was on his own. The next day the Beagle sailed.

It was a challenging task. The wind-ravaged western coast of Tierra del Fuego brought dangers even more pronounced than those in the Strait of Magellan. In the Strait, at least, he had remained somewhat sheltered from the ocean winds, but on this jagged shoreline gusts of cold Pacific air blasted ships day and night. It was the weather of this part of South America that had driven FitzRoy’s predecessor as captain of the Beagle, Pringle Stokes, to despair.

Stokes, a good man and talented navigator, had been tormented by this wild world in 1828. Little by little he had been worn down, physically and emotionally. Stokes had charted his downfall in his journal, where he described the Strait of Magellan and the west coast of Tierra del Fuego with Gothic intensity. He saw beaches littered with whale skeletons, albatrosses wheeling in the air, shorelines ‘lashed by the awful surf of a boundless ocean, impelled by almost unceasing western winds’. For weeks and months Stokes had carried stoically on, drawing on all his mental reserves. But there was no escape from the weather. Inside him, the shadows lengthened. He came to dread the morning blizzards, the sleet and hail that accumulated in dense layers, covering the Beagle in a crust of ice ‘about the thickness of a dollar’.37

In early June 1828 Stokes was surveying the Gulf of Peñas – the Gulf of Distress. ‘Nothing could be more dreary than the scene around us,’ he wrote. The atmosphere seemed to have assumed a horrid, mocking tangibility. ‘The lofty, bleak and barren heights, that surround the inhospitable shores of this inlet, were covered, even low down their sides, with dense clouds, upon which the fierce squalls that assailed us beat … They seemed as immovable as the mountains where they rested.’38

It was a place, Stokes concluded, where ‘the soul of man dies in him’. Sinking under the strain, he despaired, for his crew were beset by pulmonary complaints, hacking coughs and wheezing chests. By midwinter Stokes had locked himself in his cabin and was refusing to come out. Six weeks later, back at Port Famine, he pulled out a pocket pistol and shot himself in the head. He died eleven days later.

Captain King had written:

Thus shockingly and prematurely perished an active, intelligent and most energetic officer, in the prime of life. The severe hardships of the cruize, the dreadful weather experienced, and the dangerous situations in which they were so constantly exposed – caused, as I was afterwards informed, such intense anxiety in his excitable mind …39

As Stokes’ replacement, FitzRoy was to face the same challenges, the same hostile landscape and weather. It was not long before he encountered them. At Cape Pillar – the western entrance of the Strait of Magellan – FitzRoy experienced ‘gloomy days, with much wind and rain’ and gusts that blew violently from the mountains.40 The coast, he decided, had ‘a dangerous character’. Christmas passed, with the ship sheltered from the north-westerly winds in a weather-beaten cove he called Latitude Bay. These early experiences set a template for the months that followed, with FitzRoy using all his skill to navigate gales that constantly drove them towards the shoreline. Only on clear days could he take measurements or organise boat trips to the land. For the most time the crew were marooned on the Beagle, embroiled in skirmishes with thieving native Fuegian tribes and left to gaze at the ‘multitudes of penguins’ and swallow-like birds that skimmed and twisted over the ocean.

The bad weather continued into March – ‘rainy and blowing’. By now the Beagle had reached the southern tip of the continent. They had seen the striking outline of York Minster – ‘a black irregular shaped rocky cliff, eight hundred feet in height’, rising like an incisor almost perpendicularly from the sea – named by Cook, on his circumnavigation fifty years earlier, after the cathedral in his home county. At the end of the month they were passing the islands at the far south of the continent, winds still blowing cold and fresh. ‘From the season, the appearance of the sympiesometer, and the appearance of the weather,’ FitzRoy noted on 25 March, ‘I do not expect any favourable change until about the end of the month.’41

Perhaps FitzRoy had gained a feel for the atmosphere or had noticed a trend in his meteorological journal, because his hunch turned out to be right. At the end of March the weather did improve as FitzRoy steered the Beagle into Orange Bay – ‘a large, roomy place, with an even bottom’. After almost five months at sea many of the men had colds and rheumatic pains and FitzRoy decided the time was right to rest. A quiet spell, he reasoned, would be not just timely but prudent, as his barometer and sympiesometer were giving unusually low readings. With his experiences of the Rio de la Plata pampero still fresh in mind, the possibility of navigating into another storm was too much to risk.

Yet, oddly, no storm came. Despite the readings the weather was now as settled as at any time in the last few months. The pleasant spell continued the next day, and the next, in complete variance with his pressure readings. By 5 April FitzRoy was mulling the contradiction openly: ‘Two more days with a very low glass, shook my faith in the certainty of the barometer and sympiesometer.’ They were now giving unusually low readings of 28.94” and 28.54”.42

This peculiar weather endured until the middle of the month. Attempts to sail were frustrated by a lack of wind, as laughable a problem at Cape Horn as a want of sand in the Sahara. Finally on 17 April FitzRoy managed to guide the Beagle into open sea, passing the little outcrop of rocks that marked the extreme end of the South American continent, rounding Cape Spencer in so much fog that he mistook it for Cape Horn itself, the lower part of the rock looking, he noted, like ‘the head of a double horned rhinoceros’.

Anchored at the foot of the continent and the weather staying fair, FitzRoy decided to organise a bold boat expedition to Horn Island. Sir Francis Drake had claimed to have landed there on his circumnavigation in 1577, though this may have been a hollow boast. Certainly few had set foot on the island in the years since. On 18 April FitzRoy carried out a scouting trip. ‘Many places were found where a boat might be hauled ashore,’ he discovered. It seemed possible that instruments might be carried to the summit. By the morning of the 19th FitzRoy had organised a party to visit the island to complete a set of readings for the survey. At noon the next day they set off. They carried five days of provisions, a chronometer for measuring longitude and a range of meteorological instruments. They landed before dark, hauled their boat to safety on the north-east side of the island and, as FitzRoy added with a note of triumph, ‘established ourselves for the night on Horn Island’.43

In the quiet of that night FitzRoy and his men looked out across a stretch of water that was infamous among sailors. It was here, at 56 degrees south, that the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans crashed into one another with tremendous force. At Cape Horn powerful westerly winds raged uninterrupted by land around the foot of the globe, combining with gales that blew south off the Andes. To aggravate matters the wind agitated the shallow waters of the Cape, whipping up a short sea that was particularly venomous to shipping. In a storm the Cape was transformed into a monochromatic nightmare of spray and motion. To navigate it from the east was to confront a hundred dangers: waves, rocks and winds that could rip sails in two. On his voyage to the Antarctic James Weddell had met an American commander who had attempted the route in 1814. He cautioned Weddell, ‘Indeed our sufferings, short as has been our passage, have been so great, that I would advise those, bound into the Pacific, never to attempt the passage of Cape Horn, if they can get there by any other route.’44

Weddell had declared the middle of February to the end of May to be the worst time to attempt the Cape. Yet now, on 19 April, FitzRoy was camped out on Horn Island in comparative serenity. It was eerily still. At daybreak his party set off for the peak in fine, bright weather. As the sun reached its meridian he stopped to take a series of angles. Then they pushed on, reaching the summit shortly after. Here FitzRoy gazed across the infamous water that lay quiet like a becalmed beast. In the distance he could see as far as the Diego Ramírez Islands, sixty-five miles away. At noon he took a further set of measurements: ‘A round of angles, compass bearings for the variation, and good afternoon sights for the time completed our success.’ FitzRoy then turned his attention to a commemoration of their visit, a tower of stones eight feet high. Once it was built the men crowded around a Union Jack, drank the health of King George IV and gave three hearty cheers.

For FitzRoy it was a triumph. With courage and seamanship he had transported the Beagle and his men to the tip of South America. Here, on the wind-blasted surface of Cape Horn, he had been able to conduct observations with the ease and accuracy of a Cambridge don in his study.

FitzRoy spent the following days back on the mainland, attempting to climb a nearby hill called Cater Peak. On 25 April he scrambled to the summit but ‘found so thick a haze, that no distant object could be seen’. With his instruments at his side FitzRoy appears in the imagination as the real-life embodiment of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.

Friedrich’s 1818 oil composition shows an enlightened man on the summit of a rocky precipice, gazing into a landscape wreathed in fog. It shows the ascent of man. The figure is not fatigued by his climb, dwarfed or awed by the scene before him. He is in control. Transport Friedrich’s wanderer from the Alps to the southern coast of Tierra del Fuego. Turn the triangular snow-capped peak in the distance into Mount Sarmiento. Transform the walking pole, which the wanderer grips, into a sympiesometer. And then here is no anonymous wanderer, but Robert FitzRoy on 25 April 1830, standing defiantly at the end of the world.

* * *

Eighteen months later Captain Francis Beaufort was studying FitzRoy’s charts of Tierra del Fuego at the Admiralty in Whitehall. The Portland stone, clattering horses and coaches, politicians, bustling clerks and newspaper boys of London were completely at odds with the distant world Beaufort scrutinised in his office, drawn neatly out on an Admiralty chart.

By now, Beaufort was a respected figure at the apex of government and two years into his role as Hydrographer to the Royal Navy. He was respected and well-connected. He counted as friends the Arctic explorers John Franklin, George Francis Lyon and James Clark Ross, oceanographer James Rennell, mathematician Charles Babbage, and engineer Davies Gilbert. Over the last few months the Royal Society had invited him to sit on a steering committee to renew their charter. He had also served on the council of the Royal Astronomical Society for the last seven years. He was a founding member, alongside such talents as Humphry Davy and J.M.W. Turner, of the ultra-fashionable Athenaeum Club in Pall Mall, a haven for the scientific, literary and artistic elite. At last he had become the man he hoped to be.

Beaufort’s rise through the social and professional ranks had begun with the publication of his Asia Minor charts. Drawn with a fastidious commitment to accuracy, all twelve of them, supplemented by twenty-four plans and twenty-six views, were lauded as gems of draughtsmanship. To this success in 1817 Beaufort added a descriptive narrative account of the voyage entitled Karamania. A richly imagined blend of travelogue, geological and archaeological detail, it appealed to a Regency elite with a taste for antiquities. On its publication he sent a copy to Edgeworthstown for the verdict of his old friend. On 17 May 1817 Edgeworth replied.

My dear Francis,

How great would have been my mortification, had I been disappointed with Karamania. Had I been obliged to blame, or have been silent – On the contrary I have read it through, with pleasure & with much care … I think the book is written in a good & appropriate style, free from exaggeration, free from false ornaments & from pretension of any sort.45

From Edgeworth, who had mentored his daughter Maria’s literary works for many years and critiqued the verse of Erasmus Darwin, this was true praise. It was also a parting note. Less than a month later, on 13 June, Edgeworth died at his family home. The news soon reached Beaufort, who was left to mourn ‘my warmest and most anxious friend’. To his sister Fanny, now Edgeworth’s widow, he confessed, ‘Whatever improvement I have made in my mind must be ascribed to the impact he gave it. It was he who taught me that true education begins but with the resolution to improve, and it was he alone of all my friends who tried to wind me up to that resolution and sustain it.’46

Karamania had made Beaufort. Sir John Barrow would later describe it as ‘a book superior to any of its kind in whatever language, and one which passed triumphantly through the ordeal of criticism in every nation of Europe’.47 Thereafter Beaufort had advanced into circles of ever-expanding influence.

Full recognition, though, had come slowly. He had to wait until May 1829 before Lord Melville offered him the job of hydrographer. He was awarded £500 a year and an official address at Somerset Place on the banks of the Thames. On 12 May he had written, ‘Took possession of my new Hydrographer’s room. May it be a new era of industrious and zealous efforts to do my duty with sincerity, impartiality and suavity … not for worldly motives but from a sense of the far higher duty I owe to that Providence who placed me in this vocation.’48

Beaufort’s Hydrographic Department would become the nineteenth-century equivalent of NASA. On behalf of the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth he was conducting explorations at the very edge of human knowledge. But instead of looking out to space, Beaufort organised voyages to vibrant, tangible worlds teeming with life. With great personal authority, from his suite of offices at Charing Cross Beaufort was conducting an exploration of the world.

From his first day in post he injected a sense of purpose into the Hydrographic Department. Harriet Martineau, the writer and journalist, later described how he transformed the office from a forgotten map depot, a ‘small, cheerless, out of the way’ place, into a hotbed of ideas and enterprise. Martineau noted Beaufort’s ‘miraculous’ stamina. ‘Day by day for a quarter of a century he might be seen entering the Admiralty as the clock struck: and for eight hours he worked in a way which few men ever understand.’49 Out of principle he brought his own writing-paper and pens for private correspondence. In his spare time he was equally productive. Rising at five o’clock each morning before his official work began, Beaufort would spend an hour or more working without payment for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. His vision was to create a series of affordable and high-quality maps for the general public and day after day, year after year, he strove to achieve this ambition. In time, Beaufort’s SDUK charts would become among the most widely circulated of their day with more than one hundred available for sixpence each.

Beaufort met FitzRoy on his return from Tierra del Fuego in the autumn of 1830. There was an instant bond between the men. To FitzRoy, the hydrographer was able and proven, a contemporary of Nelson and one of the dwindling few to have served at the Glorious First of June. He also had a glamorous edge. His picaresque career seemed like something out of a Smollett novel to FitzRoy. Beaufort himself admitted that the memory of his naval career was like a ‘sort of favourite romance’.50

In FitzRoy Beaufort saw ability and potential. He was impressed by FitzRoy’s surveying work. The South American survey ‘will be acknowledged to be one of those which has eminently contributed to the credit of the country and to that of the officers employed in it’, he wrote to his superiors at the Admiralty. Soon there was talk of a new scheme. Beaufort knew FitzRoy was eager to sail to Tierra del Fuego to return three native Fuegians he had captured in skirmishes with thieving tribes. He had envisaged this as a private matter, but after conversations with Beaufort the project had evolved. Over the summer, plans for a new South American survey emerged.

Suddenly a voyage of six months had become a circumnavigation of the globe, an enterprise of several years. Not wanting to be intellectually isolated for such a long time he had asked Beaufort to find him a gentleman companion. The obvious candidate to accompany FitzRoy was a young naturalist who could assume a role similar to that of Joseph Banks on Cook’s Endeavour voyage. Beaufort wrote to a friend, Professor Henslow at Cambridge University, offering him the opportunity. Too busy, Henslow had passed the letter on to George Peacock, a fellow don. From Peacock news of Beaufort’s search extended to a recently graduated theology student and talented botanist called Charles Darwin. At just twenty-two Darwin was full of potential. Grandson of the famous Erasmus, Edgeworth’s good friend, Charles had a reputation for his ‘rejoicing enthusiasm’ and his love of collecting beetles. ‘Entomology, riding, shooting in the Fens, suppers and card-playing, music at Kings’ had been the core of Darwin’s life for the past three years. Though a very different character to the sailor, he seemed a potential match for Robert FitzRoy.51

News of Beaufort’s offer reached Darwin in late August and after a period of indecision he accepted. On 1 September 1831, Darwin wrote to Beaufort in London: ‘If the appointment is not already filled up, – I shall be very happy to have the honor of accepting it.’ The news was relayed from Beaufort to FitzRoy:

I believe my friend Mr Peacock of Triny College Cambe has succeeded in getting a ‘Savant’ for you – A Mr Darwin grandson of the well known philosopher and poet – full of zeal and enterprize and having contemplated a voyage on his own account to S. America. Let me know how you like the idea that I may go or recede in time.52

The spate of intellectual matchmaking concluded with a dinner between FitzRoy and Darwin in London. It went well. ‘All was soon arranged,’ Darwin later wrote. Although, ‘afterwards, on becoming very intimate with Fitz-Roy, I heard that I had run a very narrow risk of being rejected, on account of the shape of my nose! [FitzRoy] was an ardent disciple of Lavater, and was convinced that he could judge of a man’s character by the outline of his features; and doubted whether any one with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage. But I think he was afterwards well satisfied that my nose had spoken falsely.’

Darwin would later laugh at how the course of his life had hung, for a moment, on ‘such a trifle as the shape of my nose’. He would also recall his first impressions of FitzRoy:

Fitz-Roy’s character was a singular one, with his many noble features: he was devoted to his duty, generous to a fault, bold, determined, and indomitably energetic, and an ardent friend to all under his sway. He would undertake any sort of trouble to assist those whom he thought deserved assistance.53

By 24 October Darwin had joined FitzRoy at Plymouth for final preparations as Beaufort wrote up the hydrographic orders in London. Beaufort’s instructions were notoriously detailed. They reflected his microscopic knowledge of distant shorelines, waterways and currents. He wrote his orders like a benevolent headmaster encouraging his surveyors on to greater feats: to sketch views of the coasts, bays and anchorages, to take soundings of the shallows and the deep, list prevailing winds and fix longitudes in disputed areas. On 15 November his orders arrived in Plymouth. FitzRoy was to establish the longitude of Rio de Janeiro beyond doubt, fill in geographic gaps south of Rio de la Plata and especially around Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Islands.

Something else had caught Beaufort’s attention as well. King, FitzRoy and Stokes’ journals had been filled with descriptions of wind: ‘half a gale’, ‘a furious gale’. What did these mean? How fast did the winds blow during a pampero or a williwaw? From his own visits to South America Beaufort was familiar with pamperos, and now he felt the time was ripe to test his long-treasured weather system on a grander scale. For years he had used it in his own pocketbooks, but he had never advocated its wider use until now.

Beaufort asked FitzRoy to keep a careful meteorological register, with twice-daily barometric and temperature readings:

In this register the state of the wind and weather will, of course, be inserted; but some intelligible scale should be assumed, to indicate the force of the former, instead of the ambiguous terms ‘fresh’, ‘moderate’ &c, in using which no two people agree; and some concise method should also be employed for expressing the state of the weather.54

To the end of his instructions Beaufort attached his wind scale, barely altered from the one that he had jotted down in his journal twenty-five years before. It involved four escalating strengths of wind from 0 – calm to 12 – a hurricane. To help FitzRoy distinguish between the levels Beaufort added a quantifiable guide. Level 2 was equal to 1–2 knots. Level 6 was reached when single-reefed topsails and topgallant sails were flown. Level 12 (a hurricane) was a force ‘which no canvas could withstand’.

* * *

In December the Beagle was ready to sail. ‘Every thing is on board & we only wait for the present wind to cease & we shall then sail. —This morning it blew a very heavy gale from that unlucky point SW,’ wrote Darwin on 7 December. The storms continued for five days more. Then on 10 December the skies brightened. ‘Accordingly at 9 oclock we weighed our anchors, & a little after 10 sailed.’ All went well until they reached the breakwater, where his misery began.

I was soon made rather sick, & remained in that state till evening, when, after having received notice from the Barometer, a heavy gale came on from SW. The sea run very high & the vessel pitched bows under. —I suffered most dreadfully; such a night I never passed, on every side nothing but misery; such a whistling of the wind & roar of the sea, the hoarse screams of the officers & shouts of the men, made a concert that I shall not soon forget.55

In the face of the winds FitzRoy turned the Beagle back to Plymouth to wait for better luck. The boisterous weather continued for the next weeks, gale upon gale, storm upon storm. Pent up in Plymouth FitzRoy could do nothing but wait, since in 1831 there was still no understanding of how or why storms came. For so long a mystery to the scientific community, storms were about to be analysed like never before.