1. There are figures from the past that time seems to bring closer and closer to us. Montaigne is one such figure. We are irresistibly attracted by his openness toward distant cultures, by his curiosity about the multiplicity and diversity of human life, by the conspiratorial and pitiless dialogue he carries on with himself. These apparently contradictory traits make him seem familiar, but it is a deceptive impression: in the end, Montaigne eludes us. We must try to approach him on his own terms, not ours.

This does not mean interpreting Montaigne through Montaigne himself—a highly questionable, and ultimately fruitless, approach. Let’s follow a different track by attempting to read the essay “On Cannibals,” starting with the contextual elements that can be found, directly or indirectly, in the text itself. This will be an erratic path which at times will appear to be echoing the digressions so dear to Montaigne. I want to try to show how these contexts served to mold the text: as both constraints and challenges.

2. The first context, both literal and meta phorical, is provided, of course, by the Essais, the volume in which “On Cannibals” is included. A relationship between parts and the whole exists for all of Montaigne’s essays (and for all his books): but in this case there is a special significance. This is understood at once from the words in which the author presents his work to the reader. “Had my intention been to court the world’s favor,” Montaigne writes, “I should have trimmed myself more bravely, and stood before it in a studied attitude. I desire to be seen in my simple, natural, and everyday dress, without artifice or constraint, for it is myself I portray.” But this decision to represent his “faults to the life” and his “native form” had to come to terms, as Montaigne explains subsequently, with his “respect for the public.” In presenting to the reader the result of such a compromise—his book—Montaigne expresses a nostalgic longing for “those nations who are said to be still living in the sweet freedom of Nature’s first laws.” If he had been living among those people, he concludes, “I assure you that I should have been quite prepared to give a fulllength, and quite naked, portrait of myself.”1

On the very threshold of the Essais we meet the Brazilian savages who will reappear in “On Cannibals.” Their nakedness points at two crucial, and closely related, themes: on the one hand, the opposition between coustume and nature; on the other, the author’s intention to speak of himself in the most direct, immediate, and truest way possible. Allusions to naked savages and naked truth have nothing surprising about them. But their convergence implies an intermediate link tied to one of Montaigne’s boldest assumptions: the identification of tradition (coustume) with artificiality. Clothing, as he explains in the essay “On the Custom of Dressing” (1:36), demonstrates that we have departed from the law of nature, from that “general polity of the world, where there can be nothing counterfeit.”2 Nakedness was “the original custom of mankind”—words that clarify the already noted allusion to the Golden Age’s lack of constraints: the “sweet freedom of Nature’s first laws.”3 We find anticipated, in a concise form, some of the crucial ideas which will be developed in the Essais.4

But how widespread at that time was the association between the Golden Age, nakedness, and freedom from the constraints of civilization? Here another possible context emerges. These three motifs converge in a famous passage of the Aminta, the pastoral poem by Torquato Tasso, whom Montaigne regarded as “one of the most judicious and inventive of Italian poets, who was more highly trained in the manner of pure and ancient poetry than any other that had lived for a long time.”5 The chorus which closes the first act of the Aminta is a nostalgic evocation of the Golden Age and its naked nymphs: an age in which erotic pleasure was not constrained by honor, “that vaine and ydle name.”6 It should be added that Pierre de Brach, councillor of the Parlement of Bordeaux and author of the first translation of the Aminta into French (1584), was a friend of Montaigne’s.7 But the possibility that Montaigne, who knew Italian very well, echoed Tasso’s verses in his address to the reader must be absolutely rejected. The first edition of Montaigne’s Essais (which already included the address to the reader) appeared in the summer of 1580, a few months after the publication of the first edition of the Aminta.8 In the second edition of the Essais (1582) Montaigne added a moving reference to his meeting with Tasso at the Sant’Anna hospital in Ferrara, where the poet was confined for insanity.9

Montaigne could not possibly have read the Aminta, for chronological reasons; Tasso could not have read the Essais for reasons both chronological and linguistic (his French was very poor). The analogies between the two texts must be related to a widespread motif. This can be proven by a page of La métamorphose d’Ovide figurée, a French poetical adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, published in Lyons in 1557. The etcher, Bernard Salomon, known as “le petit Salomon,” depicted the Golden Age as the triumph of free love and nakedness: at that time, the caption reads, people lived “sans loy, force ou contrainte/On meintenoit la foy, le droit, l’honneur” (“without law, force or constraint/faith, right, honor were preserved”) (figure 2).10

The tone is less aggressive, but we are not very far from either Tasso’s denunciation of honor or from Montaigne’s lament for the “sweet freedom of Nature’s first laws.”11 But La métamorphose d’Ovide figurée suggests Montaigne to us on a different level as well. The representation of the Golden Age is framed by “grotesques”—decorations which had become fashionable at the end of the fifteenth century, after the discovery of the frescoes which decorated the grottoes of the Domus Aurea.12 In an often quoted passage, Montaigne compared his own essays specifically to “grotesques, that is to say, fantastic paintings whose only charm lies in their variety and extravagance. And what are these essays but grotesques and monstrous bodies, pieced together of different members, without any definite shape, without any order, coherence, or proportion, except they be accidental.”13

The illustrations of La métamorphose d’Ovide figurée contributed to the diffusion of this kind of decoration throughout France. A series of mid-sixteenth-century frescoes in the castle of Villeneuve-Lebrun, near the Puy-de-Dôme, was actually based on Bernard Salomon’s etchings.14 We do not know whether Montaigne was familiar with these illustrations; but they may provide a visual parallel to, and context for, the passage we have just read.

The comparison of his own work to the “grotesques” had a twofold significance, both negative and positive. On the one hand, Montaigne was suggesting what his Essais lacked: they were “without any definite shape, without any order, coherence, or proportion, except they be accidental.” On the other, he indicated what they were: “fantastic paintings,” “monstrous bodies.” In Montaigne’s tongue-in-cheek self-denigrating judgment we recognize the accompanying narcissism that his readers know so well: “whose only charm lies in their variety and extravagance.” As Jean Ceárd has shown, words such as variety, strangeness, and monster had a positive connotation for Montaigne.15 But there is something to add to their aesthetic implications.

FIGURE 2. Bernard Salomon, engraving for La métamorphose d’Ovide figurée (Lyons, 1557).

3. Montaigne had a true passion for poetry. It has been supposed, on the basis of his Journal de voyage en Italie, that he was less interested in the visual arts. Certainly, we will not find in the Journal comments on the Sistine ceiling or Leonardo’s Last Supper. But this proves only that Montaigne (who, by the way, did not record everything he saw) did not have a nineteenth- or twentieth-century guidebook in his pocket. In fact, the passages of his Journal dedicated to the villas of Pratolino, Castello, Bagnaia, and Caprarola display a definite interest in gardens, fountains, and grottoes.16 Montaigne avoided technical terms in his descriptions, which should not surprise us if we recall the ironical reference in his Essais to architects preening themselves “with big words like Pilasters, Architraves, Cornices, Corinthians, Doric and such,” all of which referred to “the paltry parts of my kitchen door.”17

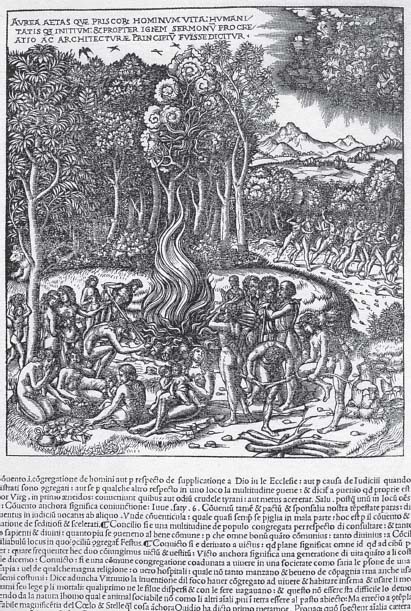

The art historian André Chastel wrote that this passage indicates first of all that Montaigne was more conversant with such ancient authors as Seneca and Cicero than with Vitruvius.18 Such a conclusion seems to me far from evident. Montaigne was presumably familiar with the vivid description of the first, uncivilized stage of human society contained in the De architectura of Vitruvius. Besides the original Latin text, reprinted many times, Montaigne could have known the French translation of 1547 by Jean Martin, itself based on an earlier Italian version by Cesare Cesariano (Como, 1521). In commenting on the passage in Vitruvius on the invention of fire, Cesariano identified the harsh beginning of human society with the Golden Age (aurea aetas) and compared those early humans to the inhabitants of the recently discovered lands of southern Asia, whom Spanish and Portuguese travelers had found still lived in caves (figure 3).19

In his essay on cannibals Montaigne described the Brazilian savages as being both primitive and similar to the people of the Golden Age. It is impossible to say whether he took these ideas from the commentaries on Vitruvius. But that is not the point. Montaigne’s ironical remark on contemporary architectural jargon does not imply a disregard for architecture. His Journal de voyage en Italie proves just the opposite.

FIGURE 3. Vitruvius, De architectura (Como, 1521).

Here is how he describes the Medici villa at Pratolino, near Florence:

There is . . . a grotto, consisting of several cells, which is the finest we ever saw. It is formed, and all crusted over, with a certain material, which they told us was brought from some particular mountain; the wood-work is all ingeniously fastened together with invisible nails. Here you see various musical instruments, which perform a variety of pieces, by the agency of the water; which also, by a hidden machinery, gives motion to several statues, single and in groups, opens doors, and gives apparent animation to the figures of various animals, that seem to jump into the water, to drink, to swim about, and so on.. . . The beauty and richness of this place cannot be conveyed by any description, however detailed.20

The fountain, built by the architect Bernardo Buontalenti, has been destroyed. We may be able to figure out what Montaigne saw by looking at another grotto, also built by Buontalenti and still extant in the Boboli Gardens in Florence.

The construction of the facade of the grotto, begun by Giorgio Vasari, was taken over by Buontalenti in 1583—that is, two years after Montaigne’s voyage to Italy—and finished in 1593. The two Prigioni by Michelangelo (today replaced by copies) were installed in the grotto in 1585.21 The fashion for grottoes had started in Italy some decades earlier. In 1543, Claudio Tolomei, in his description of the grottoes built in his Roman villa by messer Agapito Bellomo, mentioned “the ingenious artifice of making fountains, which has been recently discovered and now has been widely practiced in Rome. By combining art with nature, it has become impossible to discern which is which. Sometimes it looks like a natural artifice, sometimes like an artificial nature: in this way nowadays they have learned to make fountains which look as if they had been made by nature, not by chance but through a masterful artifice.. . .”22

Tolomei’s praise for devices characterized by “natural artifice” and “artificial nature” immediately makes us think of Montaigne’s enthusiasm for the Pratolino grotto.23 This convergence inspired by a common taste was analyzed brilliantly many years ago by Ernst Kris.24 Studying the casts made from nature by two late-sixteenth-century sculptors—the German Werner Jamnitzer and the Frenchman Bernard Palissy—Kris demonstrated that this practice was related to a widespread form of extreme naturalism, which he labeled “style rustique.” Among the prominent examples of this style he mentioned the Tuscan gardens and grottoes so warmly appreciated by Montaigne.25

FIRGURE 4. Giulio Romano, Palazzo del Te, Mantua.

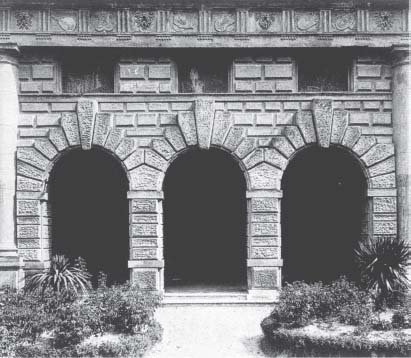

More recent research has shown that this “rustic style” had been precociously transmitted to France by Sebastiano Serlio, the celebrated architect and theorist. In the fourth volume of his influential treatise, Libro di architettura, published in 1537, Serlio identified the Tuscan order (which had been mentioned only briefly by Vitruvius) with the rustic order, and he cited as an example of this combination (mistura) the extremely beautiful Palazzo del Te, the country residence of the Gonzaga family, not far from Mantua, constructed a few years earlier by Giulio Romano.26 Serlio particularly praised Giulio Romano’s use of both rough and polished stone in the facade of the palace, making it seem “part work of nature and part artifice” (figure 4).27

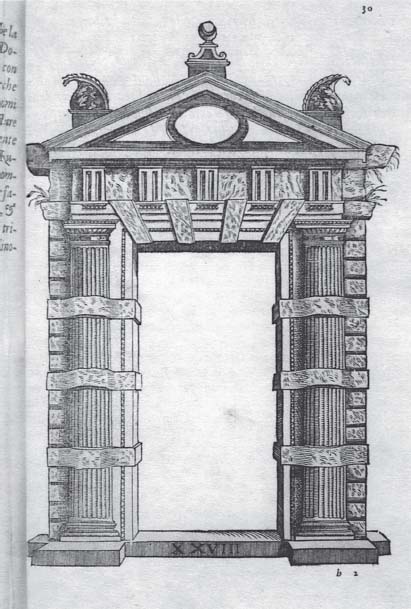

A few years later Serlio found a new patron in Francis I and left Italy for France forever. In 1551 he published in Lyons a book almost entirely dedicated to the rustic order: Libro estraordinario, nel quale si dimostrano trenta porte di opera rustica mista con diversi ordini (“Extraordinary Book, in Which Are Displayed Thirty Doors in the Rustic Style Mixed with Several Others”).28 In the introduction Serlio apologized to the (presumably Italian) followers of Vitruvius, from whom he had departed “not much,” suggesting that his transgressions had been dictated by the desire to satisfy French taste (“having regard for the country where I find myself”).29 Probably Serlio’s excuse contained a kernel of truth. His physical distance from the imposing heritage of Roman architecture could have had a liberating effect on him. In any case, through both his buildings at Fontainebleau (most of them now destroyed) and his treatise on architecture Serlio contributed to the spread of a style which developed some of Giulio Romano’s boldest ideas. A work such as Bernard Palissy’s Architecture et Ordonnance de la grotte rustique de Monseigneur le duc de Montmorency connestable de France (1563) attests to Serlio’s dramatic impact on French architecture. In order to convey to his readers the monstrosity (monstruosité) of a grotto he had built, Palissy listed innumerable details which associated a close combination of nature and the pursuit of bizarre effects: terra-cotta statues whose worn aspect simulated the effects of time; columns made of seashells; columns sculpted in the form of rocks eroded by the wind; or rusticated columns to make one think they had been repeatedly struck by a hammer; and so forth.30

Montaigne’s enthusiasm for Pratolino, Bagnaia, and Caprarola, as recorded in his Journal de voyage en Italie, was clearly related to a pervasive taste which may shed some light on both the structure and style of his Essais. It is a lead worth pursuing.

4. Antoine Compagnon has suggested that Montaigne, in writing his essays, had an ancient model in mind: the Noctes Atticae (the Attic Nights), written by the grammarian Aulus Gellius c. 150 B.C. The work consists of a series of arbitrarily arranged chapters, each of which focuses on a word, a motto, an anecdote, or at times a general topic. Compagnon has emphasized that the structural resemblance between the two works is reinforced by a series of other analogies such as the rejection of learning, the frequent use of titles related only vaguely to the content of the essays, and the huge number of quotations from a heterogeneous collection of books.31 The hypothesis is certainly convincing. But why was Montaigne, who repeatedly quoted from Gellius, so struck by his work? And in what vein did he read it?

An answer to these questions can be found in a passage from Gellius’s introduction to the Noctes Atticae. After having listed a series of elegant, sometimes pretentious titles by famous scholars, he explains how he came to choose the title for his book: “But I, bearing in mind my limitations, gave my work offhand, without premeditation, and indeed almost in a rustic fashion (subrustice), the title Attic Nights, derived merely from the time and place of my winter vigils; I thus fall as far short of all other writers in the dignity even of my title, as I do in care and elegance of style.”32

The key word in the passage, subrustice, “almost in a rustic fashion,” obviously did not imply a literal reference to peasants. The use of the rustic order by Giulio Romano in the Palazzo del Te, the Gonzagas’ splendid country home, was equally meta phorical (figure 4). What was being suggested in both cases was a deliberate, highly controlled lack of stylistic refinement. We can easily imagine how Gellius’s tongue-in-cheek modesty, as well as his dismissal of rhetorical elegance in the name of a different rhetoric—one based on simplicity and disorder—must have appealed to Montaigne, writing from the tower of his provincial castle.33 The capricious structure of Gellius’s chapters and the large number of heterogeneous quotations with which they are encrusted were made-to-order to seduce such a reader as Montaigne, himself inclined to violate the classical laws of symmetry.

In a similar spirit, in the introduction to the Libro estraordinario, Serlio proudly trumpeted his own licentiousness, which had induced him to push to an extreme Giulio Romano’s experiments by inserting ancient fragments in a mixture of different styles. These included even a previously unheard of “bestial order” (ordine bestiale): addressing himself “to those bizarre persons who are fond of novelties,” Serlio stated that he had wanted “to break and spoil (rompere e guastare) the beautiful shape of this Doric door” (figure 5).34 A similar desire for transgression, even if less brutal, is discernible in Serlio’s praise of grotesques: they, too, favored “licentiousness,” the free play of decorative elements, legitimized by examples from ancient Rome which Giovanni da Udine had not only imitated but even surpassed in the Vatican loggias.35

Rejection of symmetry, inflation of details, violation of classical norms: Serlio would have approved the loose structure as well as the uneven stylistic texture of Montaigne’s essays. The abrupt juxtapositions may be compared to the alternate use of polished and rough stone in Giulio Romano’s Palazzo del Te, representing respectively, as Serlio remarked, “works of art” and “works of nature.”36 In the essay on cannibals Montaigne cites as authorities a writing doubtfully attributed to Aristotle (De mirabilis auditis) and another to a “plain, simple fellow.” But the latter is judged to be more trustworthy, because he had lived for ten or twelve years in the New World: “This tale of Aristotle’s relates no more closely to our new lands than Plato’s. This man who stayed with me was a plain, simple fellow, and men of this sort are likely to give true testimony.”37

FIGURE 5. Sebastiano Serlio, Libro estraordinario (Lyons, 1551).

Readers of the first edition of the Essais (Bordeaux, 1580) were confronted with a text in which each essay was printed as a single, unbroken typographical unit.38 By splitting the sequence into two different paragraphs, modern publishers have attenuated the original harsh tone, but without making it disappear entirely.

5. “Une marqueterie mal jointe,” an inlay badly joined: this definition which Montaigne gave to his own writings (like the one previously analyzed about the grotesques) reveals, in addition to his customary teasing tone, a remarkable literary self-awareness. Montaigne was referring to the uneven stylistic texture of the Essais, an unevenness exacerbated by his compulsive habit of inserting additions (allongeails) of various lengths in subsequent editions.39 Some years after the death of Montaigne, another famous reader, Galileo Galilei, penned a similar phrase in the margin of his interfoliated copy of the Gerusalemme Liberata. Tasso’s narrative, he observed, resembles “more inlaid wood or intarsia than an oil painting. For, since an intarsia is a composite of little varicolored pieces of wood, which one can never combine and unite so fluidly that the contours would not remain clear cut and the colors sharply distinct in their variety, the figures are of necessity stiff, crude and without conformation and relief.” As an example of a narrative comparable to an oil painting, “soft, round, forceful and rich in relief,” Galileo mentioned Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso.40

The analogy between Montaigne’s rather indulgent self-representation and Galileo’s hostile judgment of Tasso seems to suggest once again the existence of a larger common framework. In a famous paper, Panofsky used Galileo’s text to demonstrate Tasso’s connection to the Mannerist culture of a Salviati or Bronzino. Panofsky’s definition can be extended to Montaigne as well. I am well aware that this assertion is not new. In the last few decades Montaigne has been repeatedly described as a typical representative of Mannerism.41 But the category of Mannerism, itself quite debatable, has become more and more vague. It would be prudent to use it in a strictly nominalist perspective: as a twentieth-century intellectual construction whose historical pertinence needs to be systematically checked. All the elements in the structure which we have seen emerge piece by piece—Tasso, the Pratolino grotto, Serlio, the facade of the Palazzo del Te, the intarsia as a stylistic metaphor, again Tasso—have been independently connected to Mannerism. But the tortuous course we have traveled thus far seems to me more important than our point of arrival.

6. “When I begin reading the Furioso,” Galileo wrote, “I see opening up before me a regal gallery adorned with a hundred ancient statues by the most renowned sculptors.” Tasso’s Gerusalemme, instead, gave him the impression

of entering the study of some little man with a taste for the curious who has taken delight in fitting it out with things that have something strange about them, either because of age or because of rarity or for some other reason, but are, as a matter of fact, nothing but bric-a-brac, such as a petrified crayfish; a dried-up chameleon; a fly and a spider embedded in a piece of amber; some of those little clay figures which are said to be found in the ancient tombs of Egypt; and, as far as painting is concerned[,] little sketches by Baccio Bandinelli and Parmigianino, and other similar trifles.42

“Here Galileo,” Panofsky remarks, “portrays to a nicety, and with evident gusto, one of those jumbled Kunstund Wunderkammern so typical of the Mannerist age.”43 In such a Wunderkammer we can easily imagine a cast of an insect from Palissy’s workshop, as well as “the beds . . . ropes . . . wooden swords and bracelets . . . and large canes open at one end” used by the Brazilian natives as musical instruments in their dances: objects collected by Montaigne, who (as we learn from his essay on cannibals) had them in his house.44

Aesthetic taste can act as a filter, with both moral and cognitive implications.45 Montaigne’s effort to understand the Brazilian natives was fed by his attraction for the bizarre, the distant, the exotic, for works of art which imitated nature and for people close to the state of nature. In the essay on cannibals Montaigne shed light on the moral and intellectual implications of the Wunderkammer.46

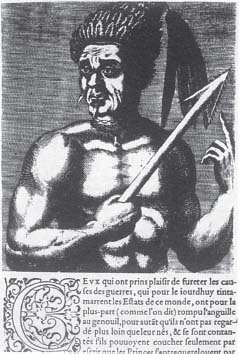

7. Collecting is an activity that aims at completeness—a principle that tendentiously ignores hierarchies religious, ethnic, cultural. We are struck by this conclusion as we leaf through Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latin et payens recueilliz de leurs tableaux, livres, medailles antiques et modernes (“The True Portraits and Lives of Famous Greek, Latin and Pagan Men, Collected from Their Pictures, Books, Medals, Both Ancient and Modern”), a large, richly illustrated in-folio volume published in Paris in 1584. Its author, the Franciscan André Thevet, was known especially as a cosmographer. His account of the French expedition to Brazil (Les singularitez de la France antarctique, 1557) had been attacked as fallacious by the Huguenot Jean de Léry. Montaigne, in speaking of the New World, dismissed “what the cosmographers may say,” and perhaps agreed with Léry’s attacks against Thevet.47 But the latter’s volume, Les vrais pourtraits, must have aroused Montaigne’s curiosity. Thevet had been working on this huge work for many years, attempting to create an accurate portrait for each individual, which he had then passed on to the engraver “pour graver et representer au naif lair et le pourtrait des personnages que ie propose.”48 The living were excluded. The portraits and the accompanying lives were arranged according to categories: popes, bishops, warriors, poets, and so forth. The cosmographer Thevet had searched well beyond Europe’s borders, including in his book even (as the title itself announced) “pagan” personages who were neither Greek nor Latin. The eighth book, on the subject of “emperors and kings,” included Julius Caesar; Ferguz, first king of Scotland; Saladin; Tamerlane; Mahomet II; Tomombey, the last sultan of Egypt; Atabalipa, king of Peru; and Motzume, king of Mexico. In this colorful company we also find Nacolabsou, king of the Promontory of Cannibals (figure 6).49

The French anthropologist Alfred Métraux, in his monograph on the Tupinamba religion, made extensive use of Thevet and praised his curiosity, the fruit of his capacity to be astonished.50 To be sure, Thevet is not comparable to Montaigne for originality and intelligence. Both, however, shared an antihierarchical attitude which permitted Thevet to include the names of the rulers mentioned above. In this version, the series enjoyed long life. In 1657 the English translation of Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, based on Amyot’s French version, was reprinted with an appendix entitled “The Lives of Twenty Eminent Persons, of Ancient and Latter Times.” This consisted of a selection from Thevet’s Pourtraits, including Atabalipa, king of Peru (figure 7).51

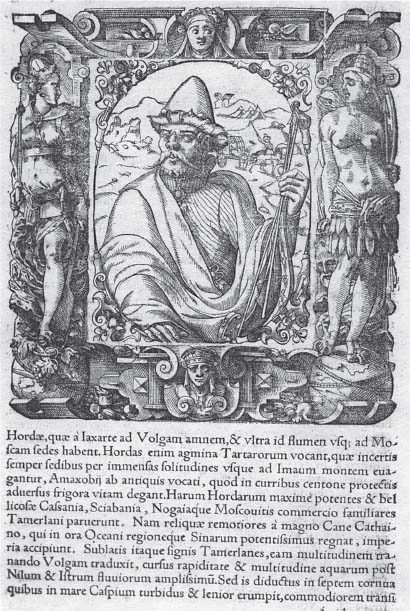

This medley was an essential component of Thevet’s project. The Vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres was modeled on the Elogia virorum bellica virtute illustrium and on the Elogia virorum litteris illustrium, two in-folio volumes published in Basel in 1577. They were a product of the museum that their author, Paolo Giovio, had built at his villa near Como. His collection of portraits of famous men (kings, generals, scholars), housed in the Museo Gioviano and subsequently dispersed, had been inspired by a classical model: the seven hundred portraits of illustrious men described by Varro, the great Roman erudite, in one of his lost works, the Imagines or Hebdomades.52 In his historical writings Giovio paid careful attention to the Ottoman Empire, and in general to events transpiring outside Europe.53 His Elogia virorum bellica virtute illustrium included African and Asian kings, but none from the Americas (figure 8).

FIGURE 6. Nacolabsou, king of the Promontory of Cannibals (from André Thevet, Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres (Paris, 1584).

FIGURE 7. Atabalipa, king of Peru (from André Thevet, Lesvrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres (Paris, 1584).

The Museo Gioviano possessed a portrait of Hernán Cortés and an emerald in the shape of a heart, which the explorer had donated.54 Among the objects of New World provenance in Thevet’s own cabinet of curiosities could be found the famous Aztec manuscript the Codex Mendoza, now at Oxford. It had been transcribed for Charles V, stolen from a Spanish galleon by a French pirate who donated it to Thevet, who, in turn, sold it to Richard Hakluyt.55 The portraits of the American kings included in Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres had been inspired by the Codex Mendoza.56

8. The taste for the exotic and the passion of the collector obviously inspired Montaigne to include, in the essay on cannibals, the translation of two Brazilian songs which he warmly praised.57 Montaigne has been seen occasionally as the founder of anthropology, as the first who tried to avoid the ethnocentric distortions involved when we approach what has been referred to as “the Other.”58 But by seeing him thus we impose our words on Montaigne. Instead, we could learn from him, using his own language.

Montaigne can also be considered an antiquarian, even though sui generis.59 This statement is almost paradoxical, since antiquarian for more than two centuries has been synonymous with pedant: Montaigne hated pedantry. But a passage in the Journal de voyage en Italie might make us think that the label was justified. During his visit to the Vatican Library, Montaigne saw a Virgil manuscript which he thought he could date, on the basis of its elongated narrow characters, to the age of Constantine. Lacking in the manuscript were the four autobiographical verses (“Ille ego qui quondam . . .”) which had often been printed in the Aeneid. This convinced Montaigne that he was justified in assuming those lines to be apocryphal.60

Montaigne was right on this last point.61 His earlier hypothesis on the date was less accurate. The manuscript which he saw at the Vatican was identified long ago with the so-called Vergilius Romanus (Vat. lat. 3867) (figure 9).62 After decades of debate, scholars now tend to date the manuscript toward the end of the fifth century A.D., a century and a half after the approximate date suggested by Montaigne.63 This scarcely diminishes the originality of his observations. Half a century before, the French antiquarian Claude Bellievre had also examined the Vergilius Romanus, noticing the elongated form of its letters as well as an orthographic detail (“Vergilius” instead of “Virgilius”) which had already been pointed out by Angelo Poliziano in his Miscellanea.64 But Montaigne had never read Poliziano’s philological writings. He was not a philologist; moreover, he could not have been a paleographer; paleography, in the modern sense of the word, emerged only in the late seventeenth century. But his attention to a detail such as the form of the letters in a manuscript was part of a boundless curiosity for the concrete, the specific, the singular. This was the attitude with which, as he said in his essay on education, an imaginary pupil should have been inculcated: “Let an honest curiosity be instilled in him, so that he may inquire into everything; if there is anything remarkable in his neighborhood let him go to see it, whether it is a building, a fountain, a man, the site of an ancient battle, or a place visited by Caesar or Charlemagne.”65

FIGURE 8. Paolo Giovio, Elogia virorum bellica virtute illustrium (Basel, 1577).

FIGURE 9. From the Vergilius Romanus (Vat. lat. 3867).

These were the topics dealt with by antiquarians, and systematically ignored by historians.66 “A man,” could have been, for instance, the “simple and ignorant fellow,” returned from the New World, who kindled Montaigne’s curiosity. Ethnography emerged when the antiquarian’s curiosity and methodology were transferred from people remote in time, as were the Greeks and Romans, to people remote in space. Montaigne’s role in this crucial intellectual turning point remains to be explored.67

9. The gaze of the antiquarian permitted Montaigne to look at Brazilian natives as belonging to a distinct and different civilization, although the word civilization did not exist as yet.68 He refused to label their poetry barbarian (“. . . a fiction that by no means savours of barbarity”; “. . . there is nothing barbarous in this idea”).69 In general, Montaigne said, “I do not believe, from what I have been told about this people, that there is anything barbarous or savage about them, except that we call barbarous anything that is contrary to our own habits.”70 But a few pages later, this purely relative meaning of barbarous acquired a negative connotation. Given that we, civilized people, are more cruel than cannibals, we are the true barbarians: “I consider it more barbarous to eat a man alive than to eat him dead.. . . We are justified therefore in calling these people barbarians by reference to the laws of reason, but not in comparison with ourselves, who surpass them in every kind of barbarity.”71

A third meaning, but a positive one this time, as applied to the word barbarian, had prepared the way for this sudden shift in perspective. Brazilian natives could be called “barbarians” or “savages” because they were still close to nature and its laws: “These people are wild in the same way as we say that fruits are wild, when nature has produced them by herself and in her ordinary way; whereas, in fact, it is those we have artificially modified, and removed from the common order, that we ought to call wild. In the former, the true, most useful, and natural virtues and properties are alive and vigorous; in the latter we have bastardized them, and adapted them only to the gratification of our corrupt taste.”72

Three different meanings. Each one implies distance between us and them: “. . . there is an amazing difference between their characters and ours.”73 Distance and diversity, as we have seen, were definitely appealing to Montaigne, on both an aesthetic and an intellectual level, so he tried to make sense of the life and customs of those strange populations. Then, with a sudden shift of perspective he looked at us, civilized people, through the eyes of the Brazilian natives who had been brought to Rouen, where they stood before the king of France. What they saw, and what he saw through their eyes, made no sense at all. At the end of his essay, he recorded their astonishment when confronted with our society. Even though his words have been quoted innumerable times, they are still painful and hard to read:

[They said] that they had noticed among us some men gorged to the full with things of every sort while their other halves were beggars at their doors, emaciated with hunger and poverty. They found it strange that these poverty-stricken halves should suffer such injustice, and that they did not take the others by the throat or set fire to their houses.74