Wallace resigned the guardianship after Falkirk, his standing and the support of the nobility had depended on his military success and after his defeat they rapidly declined. His ascendancy had been brief and there could be no second chance. With no earldom or position of prominence to fall back on, Wallace once more became a figure in the shadows of history; the records allow us only occasional incomplete glimpses of his career in the seven years between the battle of Falkirk and his capture and execution. In 1299 Wallace went abroad to the French court on a diplomatic mission, evidently to canvas support for Balliol’s kingship. He left Paris towards the end of 1300 with letters of recommendation from Philip IV to the Pope and presumably went to Rome. In 1303 Wallace was once more in Scotland, where he returned to the fray, though this time as one among several leaders of the struggle against the English.

The ruins of Torwood Castle stand in the ancient Torwood north-west of Falkirk. Wallace and his remaining followers would have crossed the River Carron at Larbert, two miles to the south, to take refuge here after their defeat. (author’s photo)

Edward I remained in Stirling after the battle for the next two weeks. Despite the scale of the defeat at Falkirk the battle was not decisive, the Scots were not subjugated, but it did mark the beginning of a grimmer phase of the struggle. The Scots were now fighting with their backs to the wall. Not for another 16 years would the Scots dare to meet the English in open battle. North of the Forth the Scots remained in control though Edward’s raiding parties burnt their way across the country north of Stirling. Then as a result of MacDuff’s support for Wallace they left a trail of destruction through Fife as far as St Andrews. Stirling Castle once more fell into English hands at this time and was not retaken by the Scots until late in 1299. The English raided Perth but the Scots burned the town themselves and withdrew before the English arrived. The English army was still having supply difficulties and Edward was still at loggerheads with a section of his barons who continued to make difficulties and wrangle over his delay in confirming the charters. The Earl Marshal and the Earl of Hereford departed, taking their feudal contingents with them, as they had a right to do. This left Edward with little choice other than to withdraw from Scotland. Stirling Castle was hastily repaired and garrisoned before he moved south by way of Falkirk and Torphichen. He was at Glencorse south of Edinburgh by 20 August. The king turned west at this point and marched to Ayr, intending to settle with the rebels of the south-west. He reached the town a week later but found it empty and burnt and the castle slighted, on Robert Bruce’s orders, so that it would be of no further use to the English. Edward had expected supply ships from Ireland to meet him at Ayr but they failed to arrive and Guisborough tells us that ‘For fifteen days there was a great famine in the camp.’ The army turned south despondently and trailed across the miles of barren moors into Nithsdale, then on to Lochmaben where Robert Bruce’s castle was captured. Edward garrisoned the castle and spent time ensuring that the defences of both Lochmaben and nearby Dumfries were in order for he had no intention of abandoning that part of Scotland still under his control. Robert Clifford was left in charge of Lochmaben while Edward moved on to Carlisle, where he arrived on 9 September. Losses of horses in Scotland had been particularly high and the eight-week campaign had been hugely expensive. Edward had won a great victory but Scotland was not conquered and the campaign had yielded few results. In Carlisle Edward distributed the forfeited lands of the Scots who had opposed him in battle among his followers as a reward for their services. Many of these estates were still in Scottish hands and the English nobles to whom they were awarded would, as Edward well knew, have to support him again in Scotland to gain possession. The castle at Jedburgh was still in Scottish hands and Edward made a diversion there to supervise the siege before returning south towards the end of October.

In 1298 Edward I built a wooden ‘peel’ at Lochmaben to tighten his grip on Annandale. In the Middle Ages Annandale offered the only practical route north on this side of the country and the castle at Lochmaben stood guard over it. (author’s photo)

Caerlaverock Castle, built in the late 12th century by Aymer Maxwell, is superbly situated on the Solway coast in Dumfriesshire. The castle is triangular in plan with towers and a massive gatehouse at the corners, all surrounded by a wet moat. (author’s photo)

Late in 1298 Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick and John Comyn the younger of Badenoch were elected as joint Guardians of Scotland but this arrangement was short-lived and the guardianship devolved on a succession of leaders, of whom the Comyns were invariably in the forefront. Despite divisions within the leadership and the country itself the national struggle against English domination continued unabated in the name of King John. The only parts of the country still under English domination were parts of Dumfriesshire and the south-east of Scotland where English-held castles clustered more closely than elsewhere.

The memorial erected in 1685 at Burgh-by-Sands on the Solway coast to Edward I who died here on 7 July 1307. (author’s photo)

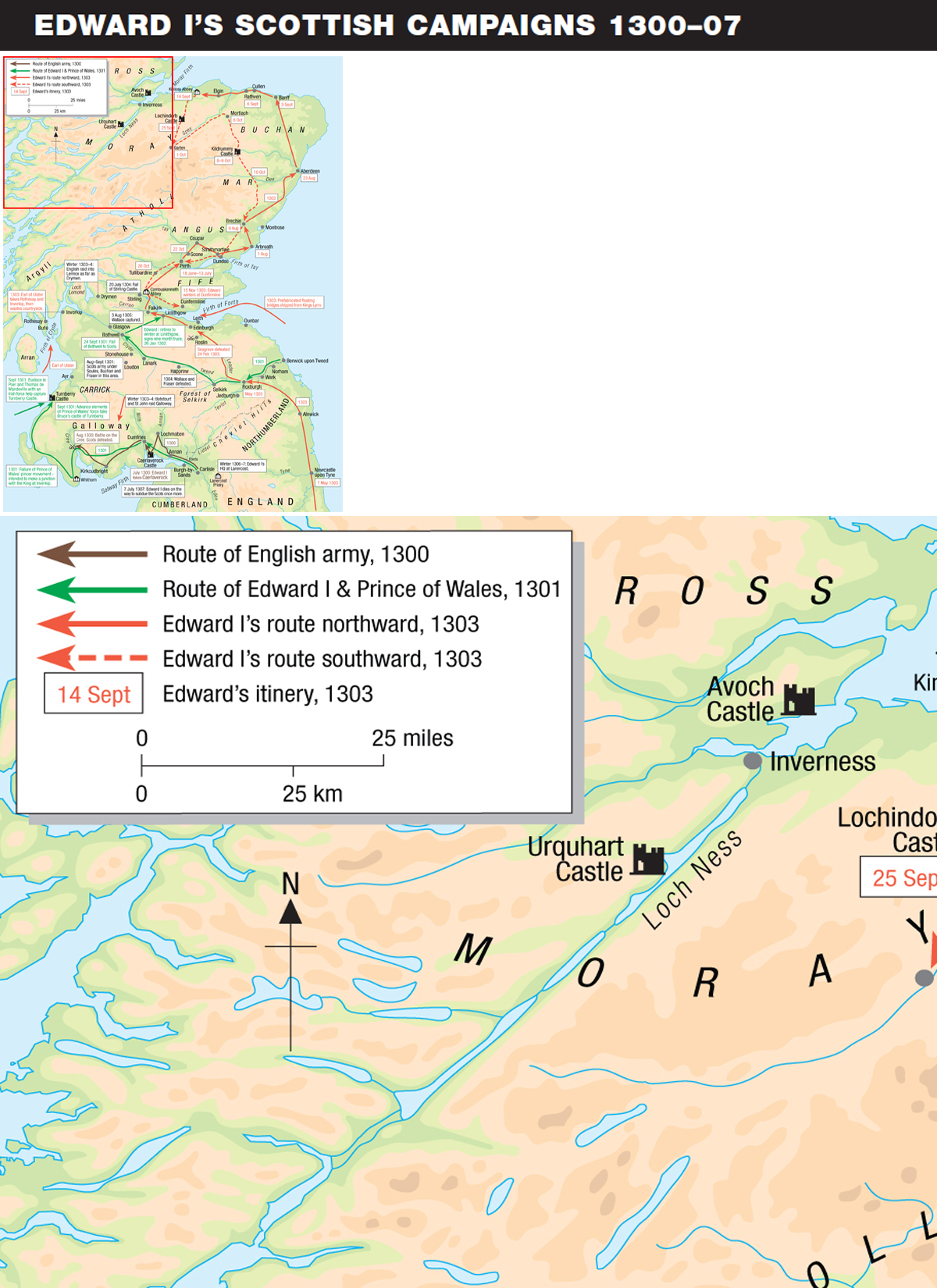

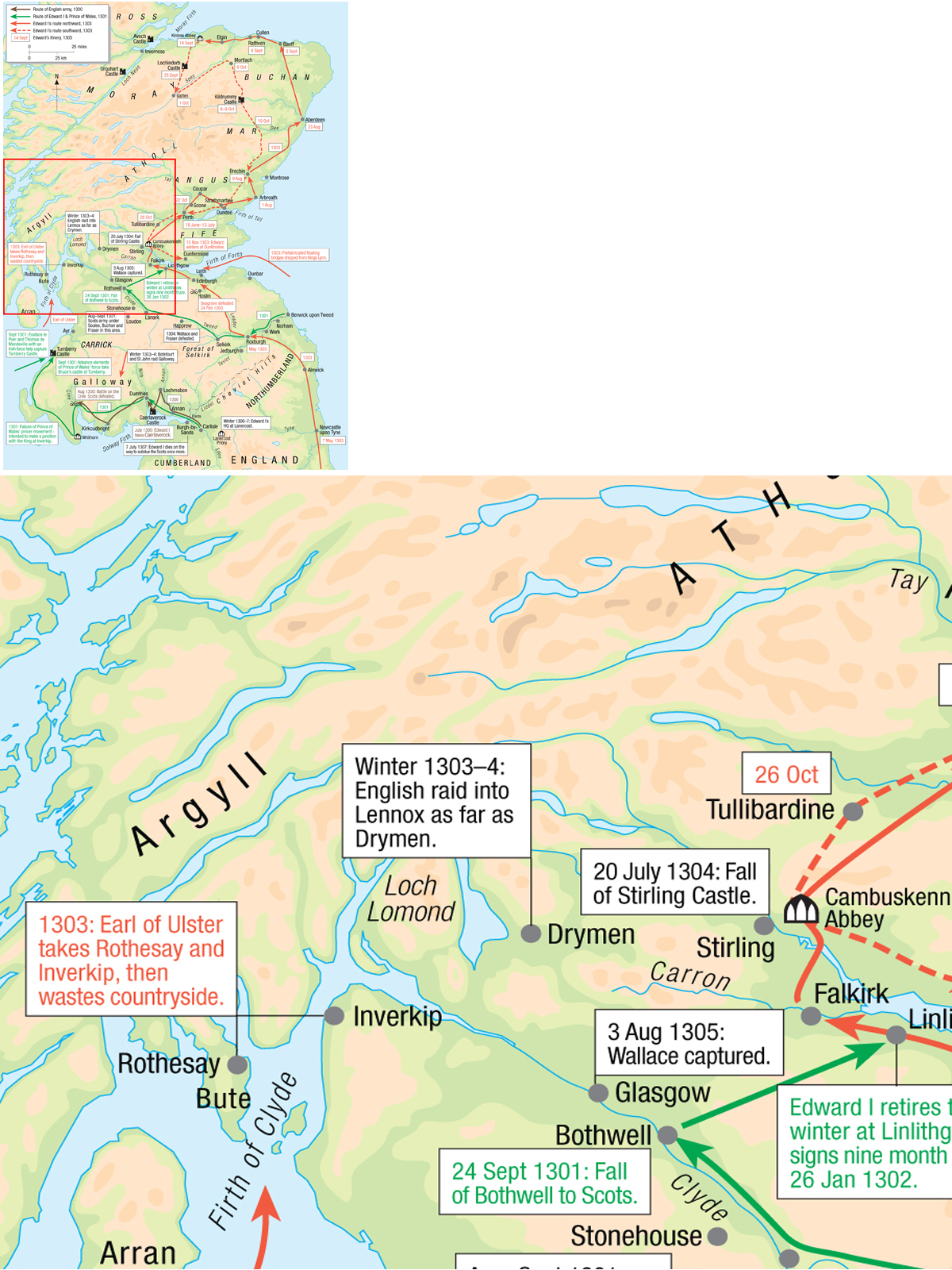

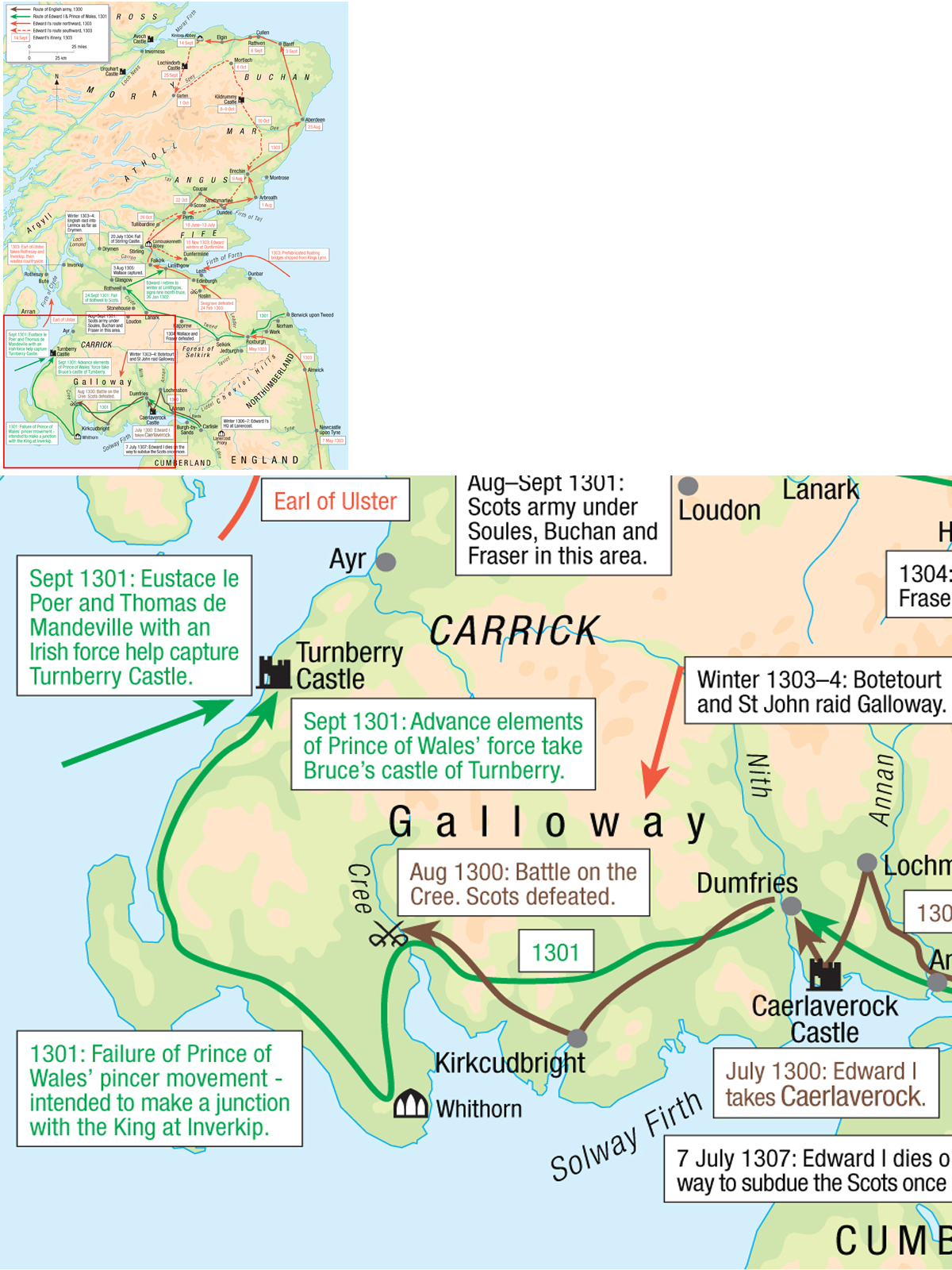

At the end of 1298 while still in the north, Edward I issued a summons for troops for a campaign in 1299 but this did not materialise and it was not until the summer of 1300 that he returned to Scotland. The campaign of that year aimed at prising loose the grip that the Scots had in the meantime re-established on the south-west of Scotland. Caerlaverock Castle was besieged and captured, after which the king advanced into Galloway and confronted a Scottish army led by the Earl of Buchan and John Comyn of Badenoch on the River Cree. In the ensuing battle the Scottish cavalry, which seems to have made up a large proportion of their army, was once again soundly defeated. Edward regretted that he had no Welsh troops with him to pursue the fugitives into the wild country where they fled and took refuge. In 1301 Edward I launched a further campaign in Scotland with the intention of taking and holding the natural line formed by Tweeddale and Clydesdale. The army invaded Scotland in two divisions, the larger, under the king, advanced from Berwick. The smaller force, under Edward of Caernarvon, now Prince of Wales, advanced into the south-west so that, in his father’s words, ‘the chief honour of taming the pride of the Scots should fall to his son.’ The two forces were intended to carry out a pincer movement and effect a junction at Inverkip. However. vigorous resistance by the Scots, combined with desertion among the foot prevented this and the prince was forced to retire to Linlithgow where his father had established his winter quarters. In January 1302 Edward I agreed a nine month truce with the Scots and when this expired he summoned troops to assemble in May 1303. In the meantime his lieutenant in Scotland, John de Segrave, set out to raid into a Scottish-held part of Lothian to the west of Edinburgh. On 24 February 1303 near Roslin the leading brigade of Segrave’s poorly co-ordinated force was surprised and routed, with serious casualties, by a Scottish mounted force, whose leaders, it is thought, included William Wallace. Segrave was wounded and captured and, though the second brigade came up in the nick of time and rescued him, the affair was very nearly a major disaster and the Scots took heart from the encounter.

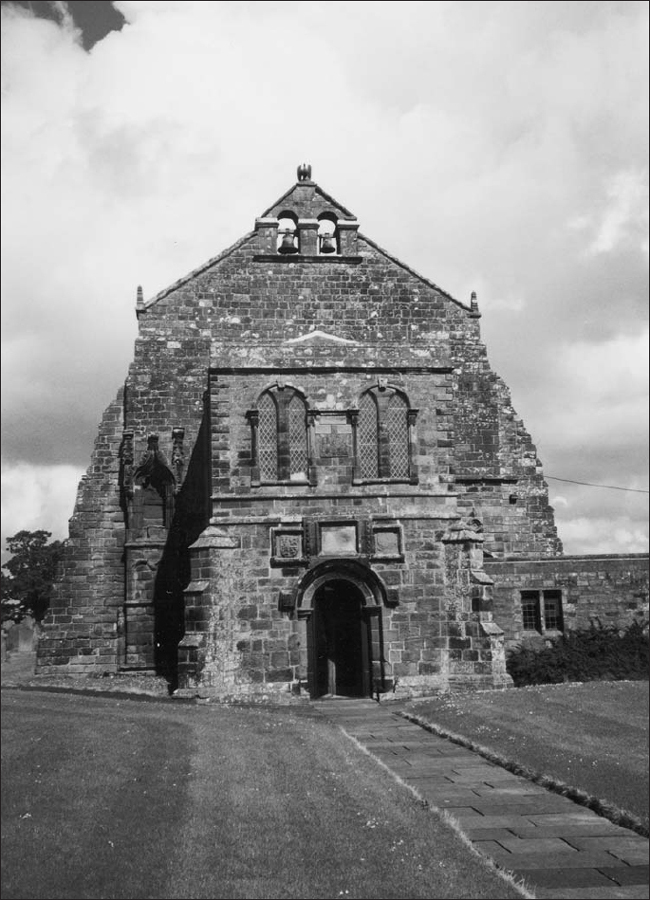

The nave of the abbey of Holm-Cultram is all that remains of the once important monastic house where Edward I’s brain and entrails were interred after his death at nearby Burgh-by-Sands. (author’s photo)

The square motte of the castle of Sir John Graham, who fell at Falkirk, is well-preserved and sited on the slopes of Cairnoch Hill, overlooking the Carron Valley about eight miles southwest of Stirling. (author’s photo)

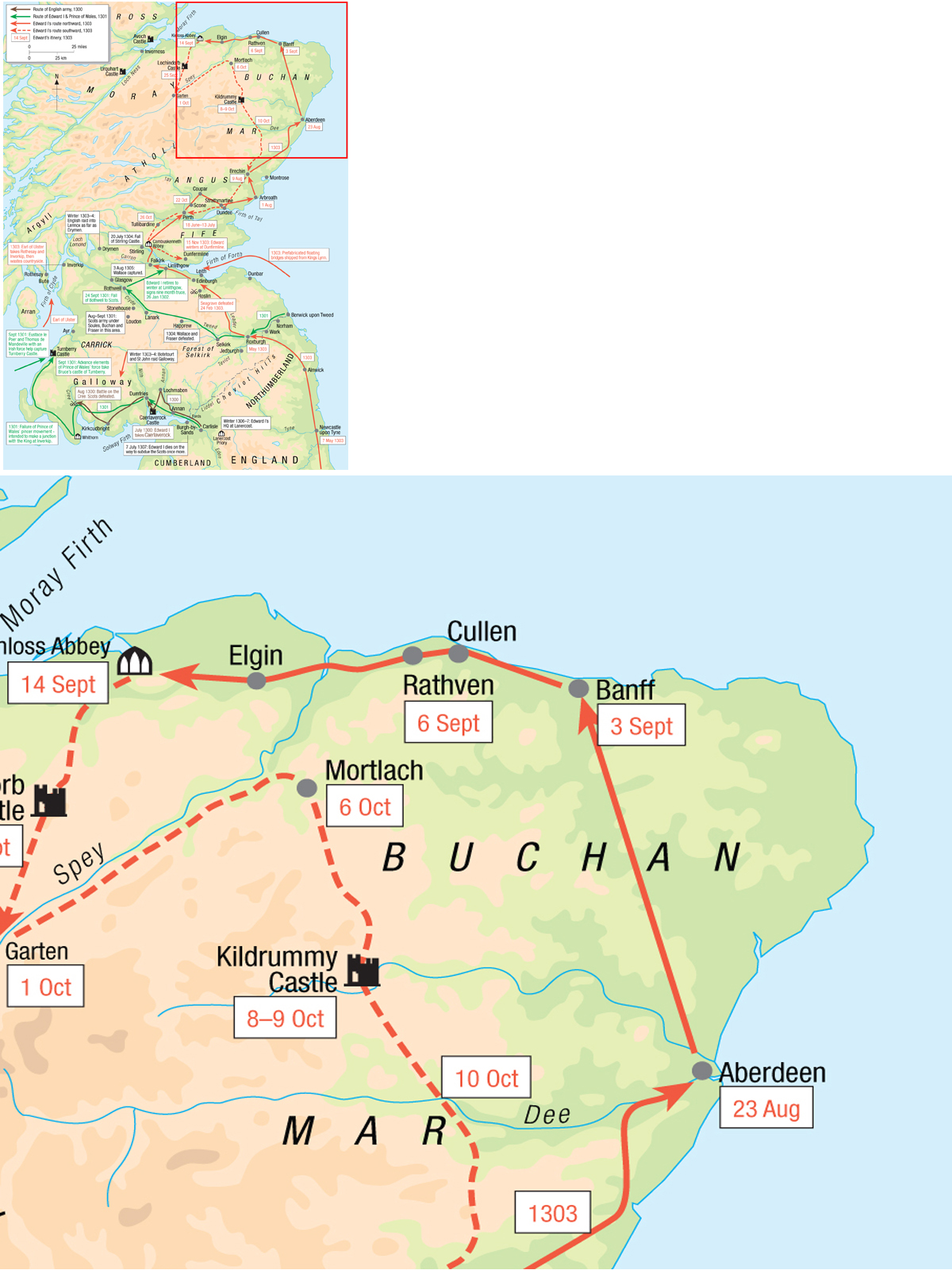

Edward I set out from Roxburgh in June 1303 with a strong cavalry force and about 7,000 foot, aiming ‘to make an end of the business.’ Previous summer campaigns had failed to subdue the obstinate Scots. This time the king intended to keep an army in the field all year round, as he had when he tamed the Welsh, and to allow the Scots no respite. At huge cost, three pre-fabricated pontoon bridges were built and transported in a fleet of 27 ships. Edward advanced into Scotland in easy stages, ‘on every side he burnt hamlets and towns, granges and granaries… unsparingly.’ The Earl of Ulster with troops from Ireland captured the castles of Rothesay and Inverkip in the west, then turned to plundering the surrounding countryside. The Scots were unable to field an army equal to confronting the English in battle, they could only snap at their heels as they advanced relentlessly. The floating bridges were probably in place across the Forth early in June, allowing the English army to by-pass Stirling Castle and march north to Perth and then to Kinloss on the Moray Firth, where the king received the submissions of the northern magnates. The king returned by a circuitous route through the mountains to Dunfermline where he spent the winter months of 1303–04. Edward still had a sizeable army in the field and operations continued throughout the winter; a raiding force over 1,000 strong penetrated into the Lennox as far as Drymen; John de Botetourt and John de St John raided Galloway in strength, with four bannerets, 141 men-at-arms and 2,736 infantry. Troops commanded by Segrave, Clifford and Latimer surprised and routed a Scottish force led by William Wallace and Simon Fraser at Happrew in Tweeddale.

The small Scottish army led by John Comyn of Badenoch made several forays against the English from their base in the mountains, but their situation was desperate and, realising that defeat could bring ruin and an end to Comyn power in Scotland, the laird of Badenoch sued for peace. Edward’s terms were lenient and the Scots submitted. In return they were granted life and liberty under their old laws and freedom from forfeiture of their lands. A few prominent rebels were singled out for temporary banishment, among them John de Soules, the guardian, who preferred permanent exile in France. No terms were offered to William Wallace, the king’s enemy, who remained defiantly at large despite every effort on Edward’s part to capture him. That he could do so reflects the popular support he could still rely on.

William Oliphant, the governor of Stirling Castle asked Edward’s leave to send a messenger to John de Soules to ask what terms the castle might be surrendered on. The king refused the request and on the 22 April the siege of the castle began in earnest. It was a social as well as a military occasion and the king had an oriel window constructed in his town house so the ladies of the court had a comfortable vantage point. The most imposing array of siege artillery ever assembled in Scotland was brought to bear against the defences, but the garrison held out despite the fury of the bombardment, though eventually they were forced to surrender unconditionally for want of provisions. A rather comical addendum to the affair was added by the king, whose powerful new engine ‘Warwolf’, built on site at great expense, had not yet come into action. The King insisted that the siege was not over, nor were any of his troops to enter the castle ‘till it is struck with the Warwolf, and that those within defend themselves from the said wolf as best they can.’

By the summer of 1304 Scotland was firmly in Edward’s grasp, the castles were garrisoned with his troops and order was restored. The king returned to England with his army and the royal administration left York and returned to London; Edward was never to set foot in Scotland again. He appointed his cousin, John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond as his lieutenant in Scotland and, with political acumen, made sure that the Scots themselves played a large part in the administration of the country. Wallace was still at large but the net was closing and the king urged the Scots nobles to ‘exert themselves…to capture Sir William Wallace, and hand him over to the king who will watch to see how each of them conducts themselves so that he can do most favour to whoever shall capture Wallace, with regard to… expiation of past deeds.’ Wallace was captured on 3 August 1305 by a fellow Scot, Sir John Menteith. He was taken to London and led, crowned mockingly with laurel, in procession with the judges appointed to try him to Westminster Hall amid huge crowds who turned out to see the spectacle. The judgement, like the trial, was a formality and Wallace was condemned to a barbaric execution. He was dragged through the streets to Smithfield bound to a hurdle. There he was hanged, cut down while still alive and disembowelled, his entrails burned before him by the executioners. He was finally beheaded and his head displayed above London Bridge. What remained of his body was cut into quarters to be exhibited in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Berwick, Stirling and Perth.

For Edward I matters in Scotland appeared finally to be settled. However, on 10 February 1306 Robert Bruce murdered John ‘the red’ Comyn of Badenoch in the Greyfriars Church in Dumfries and made himself King of Scots. On 7 July 1307 Edward I died at Burgh-by-Sands on the Solway coast on his way north to once more hammer the Scots into submission. He was succeeded by his son, Edward of Caernarvon, who was crowned King Edward II, but his interests were far from Scotland and the sorely pressed Bruce was given a breathing space in which to establish his rule, defeat his opponents and prise loose England’s hold on his kingdom.