We take Lewis’s shortcut in reverse, minus the stop at the garden sheds. I’m being extra responsible, doubly careful, and quadruple-super-nice to Painy and her pest pals. It’s hard work, but I only have to hang on for forty-nine more minutes.

I picture every ride I’m going on, in order: Gravity Whirl, Pirate Ship, BlastoCoaster, Zipperator. I stop to let the others go ahead of me out of the Home and Garden area, through the wooden storm fence toward the kiddie midway. Penny goes first, then Andrew, then Lewis.

“Wait,” I say. “Wasn’t Lou-Ann with you?”

“I thought she was up with you,” Lewis says.

I make one complete revolution. No pink rain boots in sight. “Lou-Ann!” I yell. Of course, there is no answer. “The rest of you, stay right here!”

I charge back in the direction of the hot tubs because that’s where I saw her last. But she could be anywhere in this moving obstacle course of people. Lou-Ann is tiny. She’s only six. And if I call her she won’t answer. My stomach twists as tight as a ball of rubber bands.

“LOU-ANN!” I yell. I run through the maze of hot tubs.

Her head pops up between two giant spas. My knees bend like spaghetti so I hang onto the side of the tub nearest me for a second. Lou-Ann raises one of her pink rain boots and tips it upside down, pouring a waterfall of gravel and dirt onto the ground. She disappears between the spas again.

“Wait!” I thread through the hot tubs and find her sitting and tugging on her boot over bare toes.

I hold out my hand. “Don’t do that!” I tell her, pulling her to her feet. “You can’t just stop somewhere. We thought you were lost!”

Lou-Ann gets that rabbity look again.

“Oh, hey—it’s okay,” I say quickly. I pull in a deep breath. “Just let me know next time you need to stop.”

I walk her back to the storm fence, hanging onto her hand until we meet the others and reach the kiddie midway again.

“Hard to keep track of,” Lewis observes.

“I don’t know if I can do this much longer,” I say as we walk over to the entrance for the Bouncy Slide.

The slide attendant repeats, “shoes-off-get-in-line, shoes-off-get-in-line” over and over as if she’s an animatronic Fair attraction. The little kids kick out of their shoes and run into the snaky line, which moves up the slide’s steps and separates into three chutes. After they go up the steps I hear my sister bossing everyone around at the top so she and Andrew and Lou-Ann can slide down at the same time, three across. They scream all the way from the top to the bottom. Well, except for Lou-Ann, whose mouth forms a silent O visible above the small and somewhat gray soles of her bare feet.

“She’d make a great silent movie,” Lewis says from behind his camera. “All I need is some of that fast, tinky piano music for the background.”

Andrew trips his way out of the Bouncy Slide exit wearing his own left sneaker and somebody else’s five-sizes-too-big right sneaker, so Lewis takes him back to make a sneaker trade. After that, they all climb right into the next ride, the Loco Choo-Choo, without having to wait. The train is not the slightest bit loco and it barely choo-choos, which explains why there’s no line.

I check my watch. Only two thirty-five. Part of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity shows that moving through space is connected to moving through time, so the slower a clock moves through space, the faster it ticks. But I’m not moving and I’m surrounded by extra-slow-motion kiddie rides and the minutes on my watch aren’t ticking by at all. What would Albert have to say about that?

At the other end of the midway, I see the Pirate Ship rock way up to one side of its long arc. The Ferris Wheel circles around and around. I check my watch again. A few minutes have ticked by, but three o’clock is still twenty-four minutes away. Penny, Andrew, and Lou-Ann tumble out of the Loco Choo-Choo. Lou-Ann scampers off.

“Wait!” I run after her.

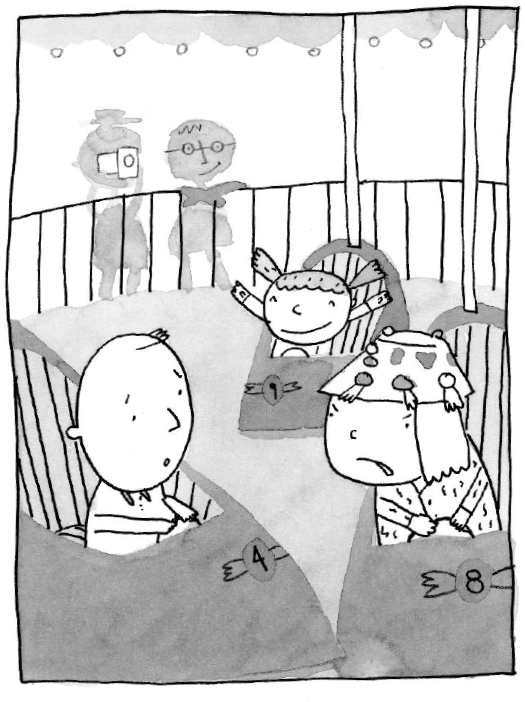

She pulls up in front of the Bitty Bumper Cars and all three six-year-olds plow into the long line. The line surges ahead, then stops while the next set of “drivers” spin around in circles and honk for three endless minutes.

While they’re waiting in line, Lewis flips open his camera. “Did anyone else talk to him last night?” he asks, looking at the screen.

“Talk to who?” I look over his shoulder at the video of the cart horses. “Oh, you mean Rip?”

I run through what I remember from the adult baking building. Mr. Hansen from the hardware store must have talked to Rip. No, no he didn’t. I try to picture the other grown-ups on the committee—the ones who were carrying all of the cakes and pies to the back.

“Rip was sitting on the bench with me. He talked a lot. But I don’t remember him talking to anyone else.”

“Think about it, Mill,” Lewis says. “He appears three different places, you’re the only one who sees him, then—poof—he’s gone.”

“Well, he didn’t disappear from adult baking,” I point out. “I was the one who left.”

But while I watch Penny and the others climb into the bumper cars, I’m remembering that Rip did just sort of show up there. And he basically vanished when Mr. Hansen took the bar off the door, then appeared again when I was heading out of the building.

“If I go with your theory that Rip’s a ghost,” I tell Lewis, “and that’s a big hypothetical if, then why do I see him at all? Why me?”

The bumper cars start up. Andrew wedges his royal blue car into a corner, front end first. Lewis aims his camera at the car.

“Maybe ghosts can tell that you know all that ‘other dimension’ stuff,” Lewis says. “The fortune-teller picked you out, too, remember? Or maybe …” He looks up from the camera for a second. “Maybe Rip wanted you to go to the graveyard.”

“So I could trip over headstones?” I joke.

“Laugh if you want, but I bet it’s something to do with those Maynard sisters,” Lewis says. “Maybe he’s helping them find The Last One.”

“Oh, and that’s me? I’m their youngest sister?”

“I don’t know,” Lewis says. “I mean, well, no.”

“We don’t even know how much of that old story is true,” I remind him. “Finding the carriage driver’s grave would help.”

Electric buzzes and crackles erupt from the tops of the bumper car rods. We watch Penny’s car bash into Andrew’s and get stuck. Then Lou-Ann crashes into them in a three-car stall. They honk their horns and turn their steering wheels in place until the ride ends.

He runs the scene backwards, then shows me the bumper car crunch-up at double speed. It’s comic genius.

“Look, Mill,” he says. “If I were you, I’d stay away from the graveyard. I wouldn’t even go behind the souvenir booth and look through the fence. I, for one, am done with flying death heads!”

“I’ll go on the Flying Death Heads with you,” Penny says, out of nowhere.

“It’s not a ride,” I tell her. “And besides, this isn’t your conversation.”

“But Lewis said it’s behind the souvenir booth and I want to—”

“Never mind what Lewis said. Dad said to be at the candy apple tent at three o’clock.” I check my watch for the trillionth time. “It’s seven minutes to three. We have to go. Grab hands!”

We haul them through Lewis’s shortcut and up the hill at a jog. Chlink chlonk chlunk go Penny’s quarters in my pocket.

Dad is at the back of the tent, pushing sticks into plain apples. Lewis gets a shot of the overflowing barrels of freshly wrapped candy-coated ones all around the inside of the tent. Ned is gone, and three new high-schoolers are doing the selling.

“Get your candy apples!” one of them calls.

The candy apple queen nods at us. “Rob, we’re way ahead now. Take your break.”

He unties his apron and comes out through the back of the tent.

“Still no word from Andrew’s mother,” Dad says. “You’re doing a great job with a big responsibility, Miller.” He puts his hand on my shoulder. “You’ve earned some time off to have fun on your own.”

He motions us onto the grass to let someone in a wheelchair pass.

“How come Miller gets to go by himself?” Penny complains. “I’m almost as old as he is.”

And how old will she have to be to stop saying that? In my mind, I click off the Pain-elope channel.

“Race you to the Gravity Whirl,” I challenge Lewis. The entire Fair stretches away down the hill in front of me. Now it feels like my hill. My Fair. I crouch in sprint position. “Ready?”

Lewis slings his camera over his shoulder. “Cut between the SportsBoosters and the roasted peanuts booth,” he directs, “then around the picnic tables, past the center stage, and straight across the field.”

“Set …” I lean forward.

“Go!”

“Be back at three twenty, boys,” Dad calls.

My brain says stop, but momentum and a pocketful of quarters pull me a few steps farther down the hill before my feet cooperate.

“Only twenty minutes?” Lewis mouths at me.

I hitch up my pants and race back to Dad. “I thought … I mean … can’t we—”

“Attention Fair-goers,” an announcer says over the loudspeaker. “Come see the artists at work in the first ever Holmsbury Fair giant pumpkin carving contest. The judges are about to select the finalists!” A few notes of trumpet music follow.

“I knew there was giant pumpkin carving.” Penny aims her giant told-you-so face at me.

“I knew, too,” Andrew pipes in. “My mom told me. Can we go?”

“Sure,” Dad says. “Miller, you guys are going to have an even longer break at six. A whole hour on your own. Is this Fair turning out great for you, or what?”

“Great,” I say. I’m trying to mean it, but ride-bracelet time will be long over at six. I shove my hands in my pockets and hit quarters. “Dad, could you at least keep Penny’s Fair money?”

“Sure,” he says. He puts his hand out and I start to empty my pockets.

“Whoa.” Dad makes a bowl with both of his hands. “No need to carry all this around. They can use change for the candy apple money box. I’ll trade it in.”

“Thanks,” I say.

I take a springy, lighter step and remind myself that twenty minutes are better than zero minutes, which is the amount of fun I’ve had at the Fair so far. I’ll just have to pack an impressive number of rides into twenty minutes.

“READYSETGO!” Lewis yells.

We take off down the hill.