Pre-Columbian petroglyphs at Sitio Barriles, Panama

1

History

It is a real tropic forest, palms and bananas, breadfruit trees, bamboos, lofty ceibas, and gorgeous butterflies and brilliant colored birds fluttering among the orchids…

—PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Natural History

Panamá lies at the southern apex of the narrow Central American isthmus, where the land is pinched pencil-thin at its juncture with South America. Shaped like a lateral S-curve, the nation is oriented east to west—a source of confusion to many visitors, who assume that Panamá runs north to south. It is cusped betwixt Costa Rica (to the west) and Colombia (to the east) and fringed by the Atlantic (to the north) and Caribbean (to the south). The country lies entirely within the Tropics between 7 and 10 degrees north of the equator.

Blessed with virtually every attribute for which the Central American Tropics is known, Panamá’s landscapes are kaleidoscopic. A pivotal region at the juncture of North and South America, Panamá is also an ecological crossroads where the biota of the two continents and the Caribbean and Pacific zones merge to produce a veritable cornucopia of biodiversity.

The region is geologically youthful, having been pushed up from the sea only a few million years ago by the cataclysmic collision of tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s surface, like a moveable jigsaw puzzle. Deep below the Earth’s crust, viscous molten rock flows in slow-moving convection currents that well up from deep within the Earth’s core, carrying the plates on their backs. Panamá rides atop the Cocos plate at its jostling juncture with the Caribbean plate. No surprise, then, that much of the 29,762-square-mile (77,381 sq km) nation is mountainous, rising to 11,401 feet (3,475 m) atop Volcán Barú.

There are only two seasons: wet (May to November) and dry (December to April), though the nation is a quiltwork of regional variations. Despite the republic’s location within the Tropics, the extremes of elevation and relief spawn a profusion of microclimates. The arid flatlands of the Azuero Peninsula and the sodden coastal plains of the Caribbean could belong to different worlds, never mind the same nation, notwithstanding their similar elevation. Moist trade winds bearing down from the east spill their water on the windward slopes of the Cordillera Central, the nation’s spine, while the lowlands at the base of the leeward slopes are left to thirst. The Cordillera thus forms rain shadows over Azuero, much of which is scrub covered, with cacti poking up from the parched earth. And though temperatures in any one place scarcely vary year-round, the smothering heat of the lowlands contrasts markedly with the crisp cool of the highlands.

FLORA

Relatively small it may be, but Panamá is clad in multiple shades of green: from swampy coastal wetlands and mangrove forests to dense lowland rain forest and, high above, cloud forests soaked in ethereal mists. In fact, this tropical Eden has 10 distinct ecological zones, including pockets of dry deciduous tropical forest and even patches of semi-desert in the parched Azuero Peninsula.

Visitors are often shocked at the humidity and year-round high temperatures; so close to the equator that the sun lasers down year-round. The greenhouse effect is aided by drenching rainfall that fuels extraordinarily luxuriant growth. As a result, Panamá boasts astonishing species diversity. More than 10,000 species of flora have been identified locally. The country is especially rich in endemic flora.

Most abundant are the ferns (678 species), found from sea level to the highest elevations. Notable, too, are epiphytes (Greek for air plants), arboreal nesters that festoon host tree trunks and boughs and use spongelike roots to tap moisture directly from the air. Prominent among them are bromeliads. These epiphytes have thick spiky leaves that are tightly whorled to form cisterns that capture both water and falling leaf litter (and the occasional unfortunate bug); the decaying matter releases minerals that feed the plant. Other epiphytes, such as dwarf mistletoe, are parasites that draw nutrients directly from the host tree. Most numerous, though are orchids: About 1,200 species have been catalogued so far, from the pinhead-sized Platystele jungermanniodes and the Flor del Espiritu Santo, or Holy Ghost orchid (the beautiful white national flower) to the black, 12-inch (30 cm) long, tapering petals of the sinister Dracula vampira. These exquisite plants are found at every elevation, from sea level to the cloud-wrapped slopes of the Cordillera.

Orchid, Panamá

Silvery gray Palma real (royal palm) rise from the lowlands like petrified Corinthian columns. With its slightly bulbous trunk, this graceful palm is beloved for its utilitarianism, including thatch for roofing. At least a dozen other species of palm are used for construction and crafts, including the sabal or Palma cana (like the royal, a towering giant), and the more slender silver thatch or guano. The shores are lined with gracefully curving coconut palm. Despite its ubiquity, it is actually an Old World species introduced to the Americas by the Spanish in the 16th century. Some palms are even adapted for cooler heights, such as the 13-foot (4 m), mountain-dwelling sierra palm, whose branches unfurl from a cello-like fiddlehead.

Vegetation zones vary with elevation and local microclimates. While it may come as no surprise that much of Panamá is smothered in dense lowland rain forest, upland areas have distinctly alpine climes and vegetation, with pine trees predominant. Higher still wildflowers emblazon soggy meadows atop the tallest peaks, where wind-scoured savannas intersperse with forests of stunted trees skulking low against howling rains.

The forests, dry and moist alike, flame with Cezanne color: Almost fluorescent yellow corteza amarilla…purple jacaranda…snow white frangipani…and flame red Spathodea, or African flame-of-the-forest, emblazon the Panamanian landscape before littering the forest floor with petals resembling discarded confetti. Many are the species, too, that produce succulent fruits. Familiar to most visitors are bananas, papayas, and mangoes, but you’ll also find—and should try—guavas (guyaba), plumlike passion fruit (chinola), oval-shaped sapote, and tamarindo, which is cusped within a long peanut-shell pod and, like guanábano, mostly finds its way into drinks.

Rain Forests

Rain forests are defined as ecosystems that receive more than 100 inches (250 cm) of rainfall per year. There are at least 13 types of rain forest, from the dense and truly rain-sodden evergreen equatorial jungles such as smother the llanuras—flatlands—of Darién and the Caribbean lowlands, to mist-soaked ethereal montane cloud forests—officially known as tropical montane rain forest—above 4,000 feet (1219 m), as on the mid-elevation slopes of Volcán Barú. Panamá has several distinct types (even at a single latitude) according to elevation and local microclimates. These crown jewels of Neotropical biota are rivaled only by coral reefs in their complexity.

The broad-leafed lowland rain forests are multi-layered, with species such as baobabs with trunks like pregnant bellies; yagruma, whose silvery leaves seem frosted; and the statuesque ceiba (or silk cotton) and caoba (mahogany), which soar skyward for 100 feet (30m) or more to form umbrellas over the solid forest canopy. To support their great height and bulk, these “emergent” giants grow massive flanges at their base, resembling rocket fins, while roots often snake along the ground for many meters. This is also because dead leaves decompose quickly in hot, humid climes (nutrients are swiftly recycled up to the forest canopy), tropical soils are thin, and trees can’t send roots deep into the ground.

Tangled creepers twine up the trunks and hang from boughs high above, much like Tarzan’s jungle. The canopy so restricts sunlight that little undergrowth grows on the forest floor, where plants compete fiercely for light. More than 90 percent of a rain forest biota is concentrated in the sunlit canopy, where an entire universe of animal and birdlife exists unseen from below.

Big Bully!

The bully of tropical trees is the giant strangler fig. This exquisite yet murderous tree (there are actually almost one thousand species throughout the Tropics) is like something from Lord of the Rings. Birthed on the branches of other trees when birds deposit their guano containing seeds, the sprouting fig sends roots creeping along the branches while long tendril roots drop to the ground and begin to take nutrients from the soil. Over decades the roots thicken and merge, twining in an eerie latticework around the host tree. Eventually the latter is choked to death (the process can take a century) and rots away, leaving a complete yet hollow mature fig. Often several fig plants will grow on the same host tree, eventually fusing together to form a compound organism with genetically distinct branches. Pocked with abundant nooks and crannies, the hollow trunk provides a perfect home for bats and other invertebrates, plus birds and lizards, all of them gifted with an abundant food source in the plentiful fig fruits (galls) that grow in clusters directly from the tree branches.

The tree owes its life to a remarkable symbiotic (mutually dependent) relationship with the tiny gall or fig wasp. Pregnant females are drawn to the tree’s fruity galls, each of which has a tiny hole through which the wasp enters. She tears off her wings as she squeezes in to lay her eggs in the stigma of the tiny flowers (both male and female) that grow within the gall; the flowers can’t pollinate each other, as they mature at different times. Duty performed, the female wasp dies. The hole seals itself. And the eggs are left to hatch. First to emerge are the males, which crawl from their eggs preprogrammed and ready to mate. They chew open the eggs of the females and inseminate them in their natal sleep. Hatching at the exact moment that the male flowers mature, the already pregnant (and winged) females get covered with pollen as they chew a hole in the gall and fly off to find their own tree. (The males also depart the gall and proceed to die.) Locating their own galls on other trees in the right stage of development, each female burrows in to begin the process anew. The pollen she carries is brushed onto the female fig flowers, completing the pollination. In her sole day of life, the female wasp thus ensures a new generation of wasps and of ficus.

Dry Forests

In pre-colonial days, seasonally dry deciduous forest covered much of the Azuero peninsula, which lies in a rain shadow and witnesses an annual five-month drought. Deforestation has vastly reduced the coverage of this tropical habitat, and only pockets remain in el arco seco (the dry arc) of southern Coclé, eastern Herrera, and eastern Los Santos provinces. Far less species-rich than wet forests, the dry forests are home to many endemic bird and animal species that include the Azuero parakeet, Azuero spider monkey, and Azuero howler monkey. The wildlife is relatively easily seen thanks to the relatively sparse distribution of trees, which shed their leaves to save water.

Typical tree species include the steel-strong lignum vitae (guayacán), with its mottled peeling bark and winged seed capsules. Guayacán is the most dense of any known wood in the world, so hard and durable that it was once used for bearings. The indigenous people used its resin to treat medical conditions, including arthritis. The logwood (campache) they used against dysentery and as a black dye. Favoring the dry forests, too, is the contorted gumbo-limbo, with its stout, massive branches and a spreading, rounded crown; it’s also known as “burned tourist” due to its shiny, smooth, reddish exfoliating bark, like the peeling skin of sunburned tourists. The smooth, papery thin bark peels off in sheets to reveal a greenish layer beneath. The oily bark gives off a gummy, turpentine-scented resin that has long been used locally for glues and varnish, handy in the manufacture of canoes. Indigenous people use the gumbo-limbo’s aromatic sap for medicinal teas. Intriguingly, the soft, spongy wood, if chopped and planted, easily takes root in the ground, for which reason it is used for fence posts.

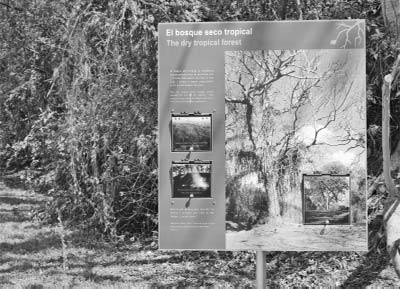

Dry forest display at Punta Culebra Nature Center, Panamá City

These dry forest trees are draped with wispy tendrils of Spanish moss, like Fidel Castro’s beard, that draw water from the air during rare rainfalls. Dodder vines also twine up tree trunks like serpents around Eden’s tree; they usurp nutrients until they kill their host trees. And orchids are also present, often growing on the tops of cactus pads.

Many flora species lie dormant throughout the dry season before exploding in riotous color with the onset of rain; an hour-long deluge can resurrect flora from sun-scorched torpor.

Mangroves and Wetlands

Dense thickets and forests of mangroves line much of the coast. Five species of these tropical halophytes (salt-tolerant plants) grow along Panamá’s shores, thriving at the margin of land and sea on silts brought down from the mountains. Thus they are frequent around river estuaries. These shrubby pioneer land-builders trap sediment flowing out to sea from the slow-moving rivers and form a bulwark against wave action and tidal erosion (by filtering out sediment, they are also important contributors to the health of coral reefs).

Mangroves rise from the dark water on a tangle of interlocking stilt roots that give them a resemblance to walking on water. The dense, waterlogged mud bears little oxygen. Hence the mangroves have evolved aerial roots, drawing oxygen directly from the air through pores in the bark (black mangroves, however, breathe through pneumatophores—specialized roots that protrude out of the mud like snorkel tubes). The roots of red mangroves, the most common species in Panamá, have evolved to filter out salt before taking up water; any salt entering via the shoot is carried to the leaves, which are then shed. White mangroves even excrete salt directly through special glands for that purpose, hence its name.

Mangrove seed pod, Panamá

Mangals—mangrove communities—are a vital habitat for all manner of animal and marine life. Rich in organic content, the muds are the base in a unique ecosystem in which algae and other small organisms thrive, providing sustenance for oysters, shrimp, sponges, and other creatures higher up the food chain. Small stingrays flap slowly through the shallow waters, while baby sharks and tiny fishes flit about in their tens of thousands, shielded from larger predators by the protective tangle of roots. Tiny arboreal mangrove crabs mulch the leaves and are preyed upon by larger, mostly terrestrial, species. Mangals are also important breeding grounds for ibis, frigatebirds, pelicans, and other waterbirds, which nest here en masse. Herons and egrets pick among the braided channels and tidal creeks. Arboreal snakes slither along the branches. Turtles bask on the mud banks. Crocodiles lurk in the silty waters, while manatees forage for food.

Aggressive colonizers, mangroves have evolved a remarkable propagation technique. The shrub blooms briefly in spring, and from the resulting fruit grows a seedling sprout. The large, heavy, elongated seeds shaped like a hydrometer, or plumb bob, germinate while still on the tree. Growing to a length of 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm), they drop like darts. Landing in mud, they begin to develop immediately. If they hit water, they float on the currents until they touch a muddy floor. The seeds can survive months at sea without desiccation and are thus capable of traveling hundreds of miles to begin a new colony. With each successive generation, the colony expands out to sea, eventually forming a great forest. The oldest mangroves form forests, often soaring 60 feet (18 m) high, that exist high and dry and eventually die on land the mangroves themselves have created.

Panamá has significant (and easily explored) mangrove forests in the Golfo de Chiriquí, Bahía de Panamá, and Golfo de San Miguel.

Many other wetland systems support profuse birdlife. Lago Gatún and Lago Bayano, the swampy freshwater bayous of Refugio de Vida Silvestre Las Macanas and Refugio de Vida Silvestre Cenegón del Mangle, and the Caribbean’s seasonally flooded San San-Pond Sak all teem with waterfowl: fulvous whistling duck…black-crowned night herons…common gallinule…pied-billed grebe…roseate spoonbills.

FAUNA

Panamá is an A-list destination for international birders. Crocodiles and other reptiles abound and are easily seen, as are mammals, such as monkeys and coatimundis. And life beneath the waves gives snorkelers and divers raptures of the deep.

Birds

Ornithologists’ hearts take flight in Panamá. The coos, calls, and caterwauling of avian fauna draw serious birders from far and wide to one of the Western Hemisphere’s premier birding locales. Its kaleidoscopic habitats provide a home to at least 972 bird species, including 12 endemics—more bird species, in fact, than neighboring Costa Rica.

Parrots (22 species) are among the most recognizable of Panamá’s birds; the forests resound with their squawks and screeches. These intelligent and garrulous creatures range from the tiny Panamá Amazon (relegated to the Pacific coast) to the giant blue-and-gold macaw. The latter, at more than a yard long, is the largest of Panamá’s six macaw species (neighboring Costa Rica has only two species), which includes a large population of scarlet macaws on Isla Coiba. Macaws are monogamous for life and are often seen—and heard—flying in pairs overhead.

Scarlet macaws

The Endangered Harpy

Most threatened of the nation’s endemic birds is the harpy eagle. The largest raptor in the Americas, this lowland rain forest dweller can attain an impressive 7-foot-wide (over 2 m) wingspan (the female outsizes the male). Its massive 5-inch-long (almost 13 cm) talons are designed for seizing monkeys and other prey from the treetops. The harpy is a strikingly beautiful bird, with white belly, legs, and underside; slate black shoulders, head, and upper wings; and a pale gray face mantled in a beardlike double crown topped by tufts, like erect ears.

Harpy eagles typically nest in the top of ceiba trees, well over 100 feet (30 m) above the ground. Slow breeders, harpy couples lay two eggs every two or three years; when the first egg hatches the second is neglected and only one chick is raised.

The species is threatened and is locally extinct in much of its former range. The Fondo Peregrino-Panamá (507-317-0350; www.fondoperegrino.org) has a conservation and breed-and-release program aimed at saving this magnificent bird.

Harpy eagle

Other quintessential tropical birds that you’re sure to see are the toucans, with their banana-like beaks. Keel-billed and chestnut-mandibled toucans are the most common, along with their cousins, the fiery-billed aracarias. Many birders flock to Panamá simply to spot the resplendent quetzal—the Holy Grail of tropical birds. Beloved for its impossibly iridescent green plumage, this pigeon-sized cloud-forest dweller is relatively easily seen on the mid-elevation slopes of the Cordillera, notably around Volcán Barú. Another cloud-forest inhabitant, the three-wattled bellbird, is now threatened.

Panamá boasts 59 species of hummingbirds, of which 4 are endemics. These tiny, high-speed creatures are named for the buzz of the blurry fast beat of their wings: at 10 to 70 beats per second, so fast that they can hover and even fly backwards. Their metabolic rate (a hummers’ heart rate can exceed 1,000 beats a minute) is so prodigious that they must consume vast quantities of high-power nectar and tiny insects. In fact, they typically eat the equivalent of their own body weight in a day (they also choose only flowers whose nectar has a sugar content above about 20 percent)! They’re a delight to watch, hovering in flight, sipping nectar drawn through a hollow extensile tongue that darts in and out of their long narrow bills.

Turkey vultures (one of four vulture species here) are common throughout the country. So, too, cattle egrets, easily seen in pastures. In fact, the republic is home to 20 species of herons and egrets, plus 6 species of spoonbills and ibis. There are as 16 species of ducks; 4 species of guans; 7 species of quails; 16 species of coots and rails; 28 species of pigeons and doves; 15 of owls, plus the closely related northern potoo; and 54 species of raptors, including osprey and American kestrel. And still you’ve barely scratched at the surface.

More than 150 of Panamá’s bird species are migrants, the majority of which are water-fowl, shorebirds, and warblers. Most are snowbirds, fleeing the North American winter via the Pacific Flyway. Baikal teal, king eiders, and white-cheeked pintail flood the shallow lakes and wetlands in multitudinous thousands. Northern jacana trot across the lily pads on their oversized widely spread feet. Glossy ibis, white ibis, and roseate spoonbills pick for tidbits in freshwater and briny lagoons, while coastal mangroves are ideal nesting sites for pelicans, Neotropic cormorants, and anhingas, colloquially known as “snake-birds” for their long slender necks cocked in an S-shape, like a cobra. And down by the shore, sand-pipers, whimbrels, willets, and American oystercatchers scurry in search of small crustaceans and similar tasty morsels.

Seabirds, too, are well represented. Red-billed tropic birds grace the sky with their snow-white plumage and trailing tails. Frigatebirds hang in the air like kites on invisible strings. Masked, red-footed, blue-footed, and brown boobies—quintessential maritime birds—nest on various offshore isles where—surprise!—even the Galapagos penguin is infrequently spotted, along with three species of albatross, six species of storm petrels, and two species of tropic birds.

See Birding, in the Planning Your Trip chapter, for information on birding, including companies offering birding tours in Panamá.

Mammals

The country has 225 mammal species, of which almost half are bats and 8 are marine mammals (see Beneath the Waves, below). The bats range from the Jamaican fruit-eating bat to the giant greater bulldog bat, or fishing bat: Named for its feeding habits, it uses echolocation to detect water ripples made by fish, which it snatches on the wing with its sharp claws as an eagle snatches salmon. Other bats emerge at night to feast on insects, which they echolocate in the darkness by emitting an ultrasonic squeak whose echo is picked up by their oversize ears.

Ibis

Kleptomaniacs of the Sky

What’s that sinister looking black bird with 6-foot (2 m) Stuka wings, a long hooked beak, and a devilish forked tail, hanging over the ocean on warm updrafts? Truly one of a kind, the frigatebird is the pirate of the sky. This kleptoparasite uses its lofty perch from which to harry gulls and terns until they release their catch, which the frigatebird then scoops up on the wing as it falls. However, they catch most of their food by skimming the ocean surface and snatching fish. These pelagic piscivores are not above snatching other seabird chicks from their nests.

Boasting the largest wingspan-to-body-weight ratio of any bird in the world, frigatebirds are supreme aerial performers and expend little energy while gliding the thermals. Thus they can stay aloft for days on end, landing solely to roost or breed. They nest in colonies, usually building rough individual nests atop mangroves in areas with a strong wind for lift on take-off.

Despite its sinister appearance, this eagle-sized bird is quite beautiful due to the iridescent purplish green sheen of the male’s otherwise jet-black plumage. The male displays a bloodred gular sac that he inflates into a heart-shaped balloon during mating season, when males sit atop their mangrove roosts ululating and preening as the larger females wing around overhead, inspecting prospective mates. The female wears a bib of white on her abdomen and breast, plus a ring of blue around her eyes, all the better to impress her would-be mate. Each pair is seasonally monogamous. The female lays one or two eggs each breeding season. Weaning takes a full year—the longest of any bird.

Unlike pelicans and other diving birds, frigatebirds lack the small preen gland that produces water-resistant oil for the feathers; thus, they need to stay dry. If they submerge, their feathers get waterlogged and they are doomed.

Frigatebirds, Isla Iguana, Panamá

Of the world’s 10 species of Neotropical wild cats, 6 prowl the Panamanian forests. Don’t expect to see them. They’re shy, elusive, and well camouflaged. The jaguars, margays, ocelots, and oncillas have spotted coats, while the low, slinky jaguarundi has chocolaty fur, and the puma ranges from tan to dark brown, depending on habitat. The massive and muscular jaguar is king of the jungle—a full-grown male can measure 8 feet in length, nose to tail. It requires a huge territory for hunting and is highly susceptible to habitat destruction. Although all the cats are good climbers, the slender margay is arboreal and has developed unique ankle joints for a life in the trees.

Ocelot

Creatures you are likely to see are the monkeys. Panamá boasts seven species, ranging from the diminutive endemic Geoffrey’s tamarin to a nocturnal monkey (endemic to Bocas del Toro), and the large yet herbivorous howlers. The latter occupy thick forests throughout the nation and range from dark brown to black, according to locale. You’ll probably hear them before you see them, as the males vocalize their presence with frightening lion-like roars. Mischievous white-faced (capuchin) monkeys are no less ubiquitous, and long-limbed, copper-colored spider monkeys are commonly seen at such venues as Barra del Colorado Island, in Gatún Lake.

Other commonly seen mammals include the slow-moving two- and three-toed sloths (perosozos), which spend most of their day snoozing in the cusp of tree branches. Down below, the adorable coatimundi can often be seen scampering roadside or along forest trails. A dark brown relative of the raccoon, it has a tapered snout and long tail held erect. Capybaras, the world’s largest rodents, forage in the wetland sloughs of the Darién (I’ve even seen them alongside the Panamá Canal), where endangered tapirs similarly prefer watery dense-forest habitats.

Born with a Watertight Skin

Panamá boasts more than 120 snake species, more than 100 frog and toad species, and almost 100 lizard species. Let’s start with the snakes, which are ubiquitous throughout the nation—masters of camouflage, they’re not always easy to see, however (not least, most species are very small and most are nocturnal, making good use of their infrared eyesight). Only about 20 species of Panamanian snakes are venomous, of which about 10 are potentially fatal to humans.

The vipers include various species of small yet highly venomous eyelash pit and palm vipers. Some are lime green. Others are banana yellow. Some are gray, brown, or even rust colored. All are supremely camouflaged according to the habitat (usually arboreal) that they prefer. The most fearsome snake in the country is the fer-de-lance (Panamanians call it the equis—“x”—for the marks on its back). This huge viper, which grows to 6 feet (1.8 m) in length, is a relative of the equally deadly bushmaster. Supremely camouflaged, it’s hard to spot among the leaf litter, despite its massive size. It’s wickedly aggressive and is the cause of the vast majority of fatal snakebites in the country. A mildly venomous, silvery black snake called the mussurana (or zopilota in Panamá) feeds on other snakes including the equis; remarkably, it is immune to even the fer-de-lance’s venom!

Boa constrictor

Slender, beautifully colored coral snakes are also potentially deadly. They’re easily recognized by their red, yellow/white, and black banding (some non-venomous snakes mimic the coral’s banding; it’s best to treat them all as venomous). And the highly venomous yellow-bellied sea snake is often encountered in large congregations in Pacific waters, notably in the Bahía de Panamá. Fortunately, they are non-aggressive and have only rarely been known to bite humans and then only under duress.

The large boa grows up to 10 feet (3 m) long and is colored with somber tones of chestnut and dusky brown; it feeds primarily on rodents, birds, and bats. Like many boas, its skin displays a remarkable pearly blue green iridescence when seen in sunlight (the sheen results from the molecular structure of the skin cells and is unrelated to the skin’s pigmentation). It prefers moist forests and open savannas and surprises its prey with a biting lunge that precedes constricting the poor beast to death. Unlike most snake species, which lay eggs, female boas produce live offspring.

Among the most beautiful species are the slender arboreal vine snakes, ever on the hunt for tasty lizards and frogs, which range from the adorable inch-long red-eyed tree frog to the giant cane toad. The latter, introduced two centuries ago to control pests in sugarcane fields, has flourished by devouring many native amphibian species, and repels predators with toxic secretions.

Panamá is famous for its poison-dart frogs, brightly colored thimble-sized critters that hop about the moist forest floors by daytime secure in the knowledge that nothing will eat them. The colors—strawberry red on Isla Bastimentos; cobalt blue and black on Carro Brujo; green and black on Isla Taboga—are warning signs that spell “Toxic!” These Day-Glo amphibians are members of the Dendrobtidae family, which produces some of the deadliest toxins known to man. The frogs secrete these alkaloid compounds through their skin when they feel threatened. One species, the silvery yellow Phyllobates terribilis, is so toxic (250 times more deadly than strychnine) that even in its normal state it is fatal to human touch. This is the true poison-dart frog after which all others are named; it is endemic solely to the rain forests of Darién and northern Colombia, whose Emberá-Wounaan communities have traditionally used the secretions to tip their darts and arrows. The earless and deaf golden frog (Atelopus zateki), endemic to the Valle de Ancón region and unique for its ability to communicate by semaphore, is considered a national mascot. Like many frog species, its population has declined markedly in recent years and it is now endangered.

Lizards, too, are everywhere, darting from rock to rock or staring you down from a shady crevice. My favorite is the forest-dwelling Jesus Christ lizard, so-named because it can dash across water on its hind legs. The semi-arboreal green and brown anoles are easily recognizable by the way males bob their heads and extend and retract their throat dewlaps, as if opening and closing a Spanish mantilla fan. You’ll fall in love with geckos—undeniably cute, bright green, and almost rubberlike, like the charming Cockney-speaking gecko of the Geico ads. You’ll probably hear them before you see them, as they love to vocalize with cheeping sounds. Don’t be surprised to find them scurrying across your hotel room ceiling! Geckos feed on tiny insects, such as mosquitoes, for which reason house geckos (which live in thatched roofs orcrevices in ceilings) are happily tolerated by Central American families.

Iguanas—fearsome-looking, dragonlike lizards—are commonly seen in lower elevation forests. Despite their size (up to 5 feet/1.5 m long) and One Million Years B.C. appearance, they’re harmless herbivores and frugivores. Panamá has several species, including the green iguana, common throughout Central America. Iguanas have a row of protective spines running down their back and along their whiplike tails, which they use to deliver painful lashes if attacked. Males have large dewlaps that hang below their chins to help regulate their body temperature and for use in courtship displays. Most remarkable is the parietal eye, a rudimentary third “eye,” or photosensory organ, atop the head to detect motion from above.

Red-eyed tree frog

Other reptilians include freshwater turtles. They’re easily seen basking on logs or mud banks in lagoons and wetland ponds. And five of the world’s eight species of marine turtles—green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, and Ridley—lumber out of the surf to lay the seeds of tomorrow’s turtles in Panamá’s sugar-fine sands. Most females typically time their arrival to coincide with full moons, when there is less distance to travel beyond the high water mark. Finding an elevated spot in the sand, she digs out a 3-foot-deep (1 m) hole with her rear flippers, drops in her 100 or so golf-ball-sized and -shaped eggs, then laboriously fills in the hole, tamps its down, scatters sand about to disguise it and, exhausted after this hours-long labor, crawls back down the beach and swims off through the surf. All five species are endangered, threatening a demise for creatures that have been swimming the oceans for 100 million years. Unlike its smaller cousins, which have an external skeleton in the form of their calcareous carapace, the leatherback (which can measure 8 feet (2.4 m) long and weigh up to 1,000 pounds) has an internal skeleton and an exterior of leathery, cartilaginous skin. Tapered for hydrodynamic efficiency and insulated by a layer of thick oily fat, it has evolved to survive staggeringly deep cold-water dives and migrations of thousands of miles. Visitors to the Azuero Peninsula are in for a special treat if they can time their visit to Refugio de Vida Silvestre Isla de Cañas to coincide with an arribada—a synchronized mass nestings of olive Ridley turtles.

Jesus Christ lizards

Olive Ridley turtles coming ashore to nest

Defying Gravity

Scratch your head as you might, you can puzzle all day and night about how the dickens geckos cling to ceilings and scurry along upside down without falling off. Sticky feet? Nah! Suction cups? Forget it! Surface tension? Getting warmer!

Touch a gecko’s foot and you’ll find it dry and smooth. No gummy adhesive, clasping hooks, or Spiderman-like suction cups. The gecko’s astounding adhesive ability is actually due to pure physics. The feat is accomplished by specialized toe pads covered with millions of spatula-tipped filaments, each a mere hundred nanometers thick—a diameter less than the wavelength of visible light. The spatulae themselves tip millions of microscopic hairs that blanket curling ridges on each toe pad on the gecko’s five-toed feet. The nanofilaments are so small that they tap into the van der Waals force, the transient negative and positive electrical charges that draw adjacent molecules together. The attractive force that holds a gecko to a surface is thus an electrical bond between the spatulae and the molecules of whatever surface the gecko nimbly scampers across.

The grip, however, is highly directional and self-releasing. The toes bond to a surface when placed downward and are released when the gecko changes its toes’ angle, breaking the geometric relationship of spatulae and surface molecule.

Arachnids, Insects, and Relatives

Panamá is abuzz with bees, wasps, and flies. There are tens of thousands of species, including hundreds of species of ant (and still counting). Dragonflies flit back and forth across the surface of pools. Some 1,600 species of butterflies—swallowtails, heliconius, scintillating blue morphos—brighten the landscapes, dancing like floating leaves on the wind. There are mantids. Cockroaches. Venomous centipedes. Big stink bugs. Katydids 3 inches long. Stick insects as long as your forearm. And beetles galore—including the 3-inch-long rhinoceros beetle—in a kaleidoscope of shimmering greens, neon blues, startling reds, and impossible silvers and golds.

Probing around with your hands amid rocks is never a good idea, as scorpions (alacránes to Panamanians) spend the daylight hours hiding in shady crevices. They stir around dusk, when they emerge to hunt crickets, cockroaches, and other insects, which they subdue with a venomous sting. With their fearsome-looking claws and sharply curving stinging tail, scorpions should be treated with due trepidation.

Beneath the Waves

The seas around Panamá are a pelagic playpen, prodigiously populated by fish and marine mammals. Coral reefs rim much of the shoreline and offshore isles. Sheets of purple staghorn sway to the rhythms of the ocean current. Leaflike orange gorgonians spread their fingers upwards toward the light. And lacy crops of black coral resemble delicately woven Spanish mantillas. A kaleidoscopic extravaganza of fish as strikingly bejeweled as damsels in an exotic harem play tag in the coral-laced waters. The species of the Pacific and Caribbean waters differ.

What a Croc!

The olive green American crocodile (cocodrilo to Panamanians), one of four species of New World crocodiles with a lineage dating back 200 million years, is a true giant of the reptile kingdom. Males are capable of attaining 16 feet (5 m) of saurian splendor. Their favored habitat is freshwater or brackish coastal lagoons, estuaries, rivers, and mangrove swamps, but they’re also numerous within the Panamá Canal and Lago Gatún. They spend most of their mornings basking on mudbanks, soaking up the sun and regulating their body temperature by opening or closing their gaping mouths. Come nightfall, they slink off into the water for the hunt. The American crocodile exists on a diet of fish (crocodiles are vital to aquatic ecology, for they wean out weak and diseased fish) and the occasional careless waterfowl and small mammals. Crocs cannot chew. They simply chomp down with their hydraulic-pressure-like jaws, then tear and swallow, often consuming half their body weight at one sitting. Powerful stomach acids dissolve bones ‘n’ all.

Crocodiles may look lumbersome but they are capable of amazing bursts of speed. They’re also supremely adapted to water. Their eyes and nostrils protrude from atop their heads to permit easy vision and breathing while they otherwise lurk entirely concealed underwater. A swish of their thick muscular tails provides tremendous propulsion.

They make their homes in burrows accessed by underwater tunnels, much like a beaver’s. They reach sexual maturity at about eight years of age. Winter is mating season. The mature males battle it out for harems then protect their breeding turf from rival suitors with bare-toothed gusto. The ardent male gets very excited over estrous females and roars like a lion while pounding the water with his lashing tail. Mating can last up to an hour, with the couple intertwined like Romeo and Juliet. Females lay their eggs during dry season in a sandy nest covered with moist, heat-creating compost. They guard their nests with gusto. Once the wee ones hatch, mum uncovers the eggs and takes the squeaking babies into her mouth and swims off with the youngsters peeking out between a palisade of teeth. Dad assists until all the hatchlings are in their special nursery, which the dutiful parents guard.

The crocodile’s smaller cousin, the caiman, is also numerous; its maximum length is 6 feet (1.8 m).

American crocodile

Spiny lobsters the size of house cats crawl over the seabed while small rays flap by and moray eels peer out from their hideaways. Sharks, of course, are ever-present, though most are harmless nurse sharks and even giant whale sharks, the largest fish on earth. Farther out, the aquamarine oceans teem with gamefish, luring anglers keen to snag dorado, tuna, wahoo, swordfish, and marlin.

The stars of the show, however, are undoubtedly the dolphins and whales (primarily humpbacks, but also sperm whales, minke whales, and even orcas) that migrate from colder northern waters and gather each winter to frolic in the nutrient-rich, bathtub-warm waters of the Golfo de Chiriquí and Golfo de Panamá. Here, they gather for courtship and to mate and give birth. On the Caribbean side, Laguna Bocatorito (near Boca del Toro) is famous for its pod of dolphins.

Social History

FIRST INHABITANTS

The first human occupants of the region now known as Panamá arrived at least 12,000 years ago as part of the great southward migration of hominids that initially crossed the Bering Straits around 4,000 years prior. The peoples of the Panamá region eventually evolved into three distinct cultures, each comprising diverse tribes ruled by caciques (chieftains) whose names would later be adopted by the Spanish to name the tribes and their regions.

The most complex culture occupied the central Pacific lowlands, centered on today’s provinces of Coclé, Herrera, and Veraguas. The tribes evolved advanced slash-and-burn agriculture as well as large villages that are the oldest and most significant archeological sites yet discovered in Panamá. Two of the principal sites, at Parque Arqueológico del Caño (near Natá) and Sitio Conte (near Penonomé), feature prominent ball courts, rows of stone columns carved with anthropomorphic motifs, and graves that once contained precious gold huacas (ornaments), such as bracelets, chest plates, pendants, and animal and fertility figurines buried with powerful caciques when they died (the cacique’s wives and servants were also buried, along with practical items such as vases, metates [three-legged stone corn-grinding tables], and pedestals with tripod legs painted with elaborate zoomorphic designs, intended to facilitate greater comfort in the afterlife). These cultures were immensely skilled in gold metallurgy using the “lost-wax” technique. Like most cultures of Mesoamerica, they lived in thatched circular huts constructed of timber and cane. Caciques occupied the largest huts, alongside the cured bodies of their ancestors. Coastal communities were adept at fashioning felled trees into sleek canoes using fire and stone tools.

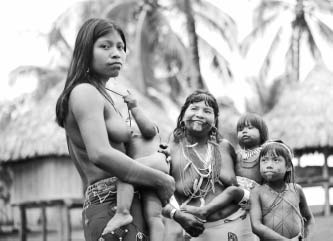

Emberá girls on Playa de Muerte, Darién, Panamå

Guaymi Indians

Farther west, the Barriles culture of the Chiriquí highlands also left significant remains. Migrating from today’s Costa Rica about 3,000 years ago, these simple agriculturalists evolved into advanced societies for whom the cultivation of corn and beans was important. Many of their life-sized stone statues depict humans clutching severed heads in their hands, and others being borne on the shoulders of slaves. The society was destroyed around 500 A.D. by an eruption of Volcán Barú. The eastern cultures of the Darién region were related to Amazonian tribes and spoke a Chibcha language. They were less evolved than their westerly counterparts, partly because virtually the entire region was smothered in dense rain forest. Little is known about these hunter-gatherers, who were the first indigenous cultures encountered by Spanish conquistadores. They were swiftly decimated. (The Emberá-Wounaan and Kuna who occupy the region today arrived from the Colombian rain forests only within the past 300 years.)

Although the various tribes are known to have traded with other groups throughout Mesoamerica, these cultures did not evolve the sophistication of groups elsewhere in the Americas, such as the Aztecs, Incas, and Maya, and no great temple complexes have been found.

THE SPANISH ARRIVE

On August 3, 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) sailed from Spain on the first of his four voyages in search of a westward route to the Orient. His three-ship flotilla manned by 90 crew comprised the caravels Santa Maria, Niña, and Pinta. After 33 days, the cry of “Tierra!” rang out as land shadowed the moonlit horizon. Thereafter, the Americas were laid open to Spanish conquistadores searching for fortune and fame.

Rodrigo de Bastidas (1460–1527) became the first European to sight Panamá in 1501, when he sailed along the coast of what is now the Comarca de Kuna Yala. Next year, Columbus arrived during his fourth and final voyage to the New World. Sailing along the coast of the isthmus, he named it Veragua and even attempted to establish a short-lived settlement at the mouth of the Río Belén (midway down the coast of today’s rain forest-clad Veragua province). Among Bastidas’ crew was Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519). After settling in Hispaniola, where he got into debt, Balboa stowed away to Panamá as one of the founding settlers of Santa María la Antigua del Darién, the first permanent settlement on mainland American soil. Through subterfuge, Balboa soon had himself appointed as governor of the region. He then set out to explore the region. He managed to baptize two caciques, Careta and Comagre. They allied with Balboa, who displayed relatively even-handed treatment of the indigenous peoples. (Some tribes, however, were vanquished with utmost severity, including the Quaregas, whose public homosexual acts enraged Balboa—he had them killed by ferocious dogs.) On September 1, 1513, Balboa set out in search of a tribe rumored to be inordinately rich in gold. After crossing the isthmus, on September 25, 1513, he spied the Pacific—the first European to do so—and famously waded into the ocean (which he named the Mar del sur, or South Sea) clad in his armor and bearing a sword and a cross. Within days he set foot on pearl-rich isles that he named the Archipiélago de las Perlas.

Balboa’s discoveries proved his own downfall. During his absence, his rivals moved to have him deposed as governor. In July 1514, a rival conquistador, Pedro Arías de Ávila (1440–1531), better known as Pedrarias, arrived with 1,500 men-at-arms as the new acting governor of Panamá. Although Balboa married Pedrarias’ daughter, in 1517 Pedrarias had his son-in-law arrested and tried for treason. Balboa and his key supporters were swiftly condemned and executed. Pedrarias had none of Balboa’s soft touch. He brutalized the native people, who were enslaved or exterminated using the most brutal methods. Those that survived were forced into the thickly forested mountains and deepest parts of the lowland rain forest.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa claims the South Sea. 19th century engraving by unknown artist

LA FLOTA…THE TREASURE FLEET

Balboa’s discovery of the Pacific positioned Panamá for a golden future as a transit point for the wealth of an empire. In 1517, conquistador Gaspar de Espinosa (1484–1537) began laying out a mule track—the Camino de Cruces—to transport treasure from the Pacific to the Caribbean port of Nombre de Díos, founded in 1510. In 1519, Pedrarias founded Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá (site of today’s Panamá Vieja) at the Pacific end of the trail, and established it as the new capital city of Panamá. The city was positioned at the narrowest point of the isthmus. Francisco Pizarro’s (1475–1541) conquest of Perú in 1532 filled the coffers of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá. Soon, the plundered wealth of the Incas—emeralds, gold, silver, and pearls—was being transferred to the Caribbean for shipment to Spain. Nombre de Díos’ harbor was too exposed to storms and pirates. A new mule trail—the Camino Real (Royal Road)—was thus laid out linking the western port to a new Caribbean port, San Felipe de Portobelo, initiated in 1597.

A Brutal Denouement

The arrival of the Spanish was a disaster for many of the region’s indigenous peoples. The conquistadores were not on a holy mission. They came in quest of gold under the quinto real (Royal fifth), in which the Spanish crown licensed explorers in exchange for receiving one-fifth of whatever treasure they brought back to Spain; the king’s galleons got priority in the treasure ports of the New World. The “Indians” (the term reflects Columbus’ belief that he had reached the East Indies by a westerly route) were seen as pathetic heathen to be slaughtered for their gold, or used as chattel under the encomienda system (a modified form of slavery, which the Pope had banned in the New World), in which conquistadores received land grants and usufruct rights to Indian labor, ostensibly with the purpose of converting the heathen to Christianity. However, the aborigines were not inclined to harsh labor. They were brutally suppressed. Those not slaughtered by musket and sword succumbed to smallpox, measles, and tuberculosis—Old World diseases to which they had no immunity—while others withered spiritually and committed mass suicides.

Ships groaning from the weight of their bullion departed Portobelo on twice-yearly treasure fleets (flotas) that arrived via Cartagena and, eventually, departed for Havana and Spain. As hundreds of galleons converged, Nombre de Díos and Portobelo held massive trade fairs. Thousands of merchants, clerics, and royal accountants arrived along with soldiers commissioned to guard the mountains of bullion that quite literally were piled high in the streets.

Pirates weren’t far behind. As the 16th century progressed, piracy became the scourge of Spain’s New World possessions. Although the majority of pirates were freelancers like Walt Disney’s fictional Captain Jack Sparrow, many were corsairs (corsarios) officially licensed by Spain’s rivals—England, France, and Holland—to harass and plunder Spanish possessions and shipping. No vessel, city, or plantation was safe from these bloodthirsty predators. For example, the image of Sir Francis Drake (1540–96) as genteel hero is pure myth; this slave-trader-turned-pirate was a ruthless cutthroat capable, like his cohorts, of astonishing barbarity befitting the times. In 1572 and 1573, Drake sacked Nombre de Díos and waylaid a silver train on the Camino Real, respectively, prompting construction of the first fortifications.

Meanwhile, in 1588, King Philip of Spain determined to end England’s growing sea power and reinstate Catholicism. A great armada of 160 ships was assembled for an invasion, but the larger and heavier Spanish galleons proved no match for England’s smaller, nimbler, and more advanced “racers” under the command of Drake, John Hawkins (1532–95), and Sir Walter Raleigh (1552–1618). The Armada was destroyed. Spain’s seafaring abilities were shattered. Her colonies were impotent as piracy and smuggling gained new zeal. Thus, in 1595, Drake and Hawkins set off with 26 ships to plunder Panamá. Alas, both Hawkins and Drake sickened of dysentery and died; Drake was buried at sea in a lead coffin off Portobelo on January 27, 1596. Nonetheless, Drake protégé William Parker (1587–1617) successfully sacked Portobelo on February 7, 1602.

Sir Francis Drake

Camino de Cruces cobbled trail near Gamboa, Panamá

During the 17th century, a new breed of pirate—the buccaneers—swept the Caribbean like a plague. This band of seafaring cutthroats had begun as a motley band of international (mostly Dutch, French, and English) ne’er-do-wells who had gravitated to Tortuga, a small French-held isle off the northwest coast of Hispaniola, where they worked the land, hunted wild boars on Hispaniola, and traded boucan (smoked meat, from which the buccaneers took their name) to passing ships. Suppressed by the Spanish, they turned to piracy and eventually set up base in Port Royal, Jamaica, where they were given official English sanction and attained infamy for their cruelty and daring under the leadership of Welsh pirate, Henry Morgan (1635–88). In 1668, Morgan attacked and captured the refortified Portobelo. For 14 days his pirates raped, tortured, and pillaged, departing only after the Spanish governor of Panamá paid a large ransom. Morgan’s crowning claim to fame, however, was his sacking of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá in 1671. During the attack, the city was burned to the ground; in 1673 a new city—today’s Casco Viejo, in Panamá City—was established some 5 miles to the southwest. (The raid on Panamá violated a peace treaty between England and Spain; when he returned to England, Morgan was arrested but exonerated. In 1674 he was knighted and returned to Jamaica as Governor, having renounced piracy.)

Following the Treaty of Ryswick, of 1697, which banned piracy and privateering, the buccaneers were finally hounded out of existence.

THE LATE COLONIAL ERA

The rivalry between England and Spain didn’t end with the Treaty of Ryswick. War between them erupted briefly 1718–20 and 1727–29. A decade of relative peace was broken in 1739 after English merchant Captain Robert Jenkins showed up in Parliament brandishing his shriveled ear, severed, he claimed, by Spanish coast guards in 1731. Relations between the countries were extremely strained and responding to public opinion, the House of Commons voted for war. A fleet was provisioned and six warships under Admiral Edward Vernon (1684–1757) set off for the Indies. They aimed straight for Portobelo, which fell to the English on November 20, 1739. Before departing, Vernon destroyed the fortifications.

Thereafter, Spain’s New World colonies sank into a century of gradual decline. Despite the immense wealth that they had generated, the Spanish crown disdained its colonies, which were treated as a cash cow to milk. Spain applied a rigid monopoly forbidding manufacture in the Americas, which were forced under threat of punishment to import virtually all their necessities from Spain at inflated prices. Even exports to Spain were taxed. Panamá gradually became a neglected, backwater province. Nationalist sentiments swept through Spain’s weakened Latin American empire, culminating in September 7, 1821, in liberation leader Simón Bolívar’s (1783–1830) creation of Gran Colombia, a federation covering newly liberated Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. On November 10, 1821, residents of La Villa de los Santos issued a letter—the primer grita de la independencia (first call for independence)—calling for independence. On November 18, the Panamanians declared independence and joined Gran Colombia. The territory proved too large to govern; a congress hosted in Panamá City in 1826 to unify all the newly freed republics into one nation collapsed. In 1830, Gran Colombia disintegrated. Panamá was press-ganged into union with the República Federativa de Colombia, of which it became a backwater province cut off from Bogotá by the impenetrable rain forests of Darién. It was an unhappy marriage and more than 50 revolts were subsequently ruthlessly suppressed.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 resurrected Panamá’s fortunes. A transcontinental railroad across the United States had not yet been built and argonauts sought a passage across the Panamanian isthmus via the old Camino de Cruces as the quickest route to California. Untold thousands were felled by disease, while others perished at the hands of venomous snakes or ruthless bandits during the grueling weeklong trek. (Even the cholera-stricken U.S. Fourth Infantry, under the command of future Civil War hero and U.S. president, Captain Ulysses S. Grant, 1822–85, were charged extortionate fees for the pack-mule passage en route to their new base in California.) Another 5,000-plus lives were lost in building the Panamá Railroad, completed in 1855 by visionary entrepreneur William Henry Aspinwall (1807–75), whose Pacific Mail Steamship Company provided the boat service between Panamá and the United States.

In 1869, French engineer Count Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805–94) completed construction of the Suez Canal, in Egypt, to grand acclaim. He was soon inspired by something grander—the dream of building a canal across the Panamanian isthmus. In 1880 Colombia sold de Lesseps the exclusive right to build a canal; he launched his Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique financed by a wildly successful public stock offering.

The Prestán Uprising

One of the most tragic events of the 19th century—the so-called Prestán Uprising—consumed Panamá in March 1885 following a revolt against Colombia by Rafael Aizpuru (1843–1919), former president of the department of Panamá. Upon hearing the news, Colombia dispatched troops from the Caribbean port of Colón to quell the uprising. With Colón now unguarded, on March 16 a group of desperados led by former Colón councilor Pedro Prestán seized control of the city. A U.S. merchant ship carrying arms was in port, but the captain refused Prestán’s demands to hand over the armaments. Prestán then took hostage the U.S. consul, the ship’s captain, and two sailors from the U.S. gunboat Galena, which was anchored in port (and which had taken possession of the munitions). Prestán demanded that the armaments be released in exchange for the lives of his hostages. It is unclear whether the arms were turned over to Prestán, although the prisoners were released. Next day, Colombian troops arrived from Panamá City. Prestán and his hoodlums were routed and fled after putting torch to Colón, which, consisting of wooden houses, was burned to the ground. Prestán was later captured and eventually hanged on August 18, 1885.

Unfortunately, de Lesseps conceived of a sea-level canal—La Grande Tranché (great trench)—and stubbornly de Lesseps refused to countenance a dam-and-lock system as proposed by more thoughtful engineers. The task proved too much given the cost and technical challenges of cutting through solid mountain and jungle, and overcoming the mighty Río Chagres. Even more formidable were malaria and yellow fever, which claimed 20,000 lives as black Caribbean laborers toiled in abominable heat and humidity. In 1889, de Lesseps’ company collapsed, causing financial ruin throughout France. Revelations of political bribery and financial fraud soon caused the French government itself to collapse, and de Lesseps and his son Charles were each given five-year prison terms for their roles in la grande enterprise.

“SPEAK SOFTLY AND CARRY A BIG STICK.”

The French attempt to build a canal caused consternation in Washington, which was angling to build its own canal. The United State’s evolving sea power made critical the need for a link between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Nicaragua was the favored route. However, one man was determined that Panamá would prevail. Parisian-born engineer Philippe Bunau-Varilla (1859–1940) had worked for the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique. After de Lesseps’ company went bankrupt, Bunau-Varilla acquired the rights to build a canal and in 1893, he organized the Compagnie Nouvelle to do so. However, his plan faltered and in 1904 Bunau-Varilla sold the rights to the United States for $40 million. The indefatigable little Frenchman then campaigned, successfully, to convince President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) and the U.S. Congress that Panamá was the preferred route. After an arm-twisting, conniving campaign that was a masterpiece of public relations, Bunau-Varilla prevailed. On June 19, 1902, Congress voted for Panamá.

Panamá was still Colombian territory, however. When the Colombian Senate rejected Washington’s proposed terms—the Hays-Herran Treaty—for the canal, the ever-wily Bunau-Varilla and President Roosevelt conjured up a plan to gain Panamá’s independence. Bunau-Varilla conspired to incite Panamá’s elite, led by Manuel Amador, to declare independence on November 3, 1903. “We were dealing with a government of irresponsible bandits,” Roosevelt stormed. “I was prepared to…at once occupy the isthmus anyhow, and proceed to dig the canal. But I deemed it likely that there would be a revolution in Panamá soon.” Not uncoincidentally, the battleship USS Nashville (with 500 Marines aboard) had already arrived off Panamá City to thwart any attempt by Colombia to land troops to suppress the separatist rebellion. Meanwhile, when Colombian troops were dispatched from Colón to Panamá City, Panamá Railroad officials arranged for the officer corps to sit up front; then they uncoupled the rear carriages, leaving the troops stranded in Colón, while the officers were arrested upon arrival in Panamá City.

The United States immediately recognized Panamá’s independence. Although he was a Frenchman, Buneau-Varilla (who wrote the Constitution for the new nation in a New York hotel room; his wife even stitched together the first flag in anticipation of the event) had already got himself appointed Panamá’s ambassador to the United States. Despite lacking the authority to do so, in Washington he negotiated a treaty granting the United States sovereignty over a 10-mile-wide Canal Zone in perpetuity at a cost of $10 million, plus an annual payment of $250,000; the U.S. was also granted rights to intervene in Panamanian affairs as it saw fit. Days later, an official Panamanian delegation arrived to find that they had been delivered a fait accomplit.

Formal work on construction of the canal by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (most of the laborers came from the English-speaking Caribbean islands) began on May 4, 1904, using dynamite and clumsy steam shovels. With the hindsight of the French experience; U.S. engineers concluded that a dam-and-lock system would be far easier to build than a sea-level canal. An ingenious plan was devised to dam the Chagres River to create a vast 23-mile-long lake, 85 feet above sea level; this, in turn, would feed three separate and mammoth locks that would raise and lower ships to sea level. Two key elements were fundamental to success. First was the brilliantly conceived flatbed train system established by Chief Engineer John F. Stevens (1853–1943) to haul out the rock excavated during creation of the 9-mile-long Culebra Cut through the continental divide. Second, and perhaps the true key to success, was medical officer Colonel William C. Gorgas’ (1854–1920) farsighted campaign to eradicate malaria and yellow fever by an all-out extermination effort against mosquitoes (Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay, 1833–1915, had laid the groundwork by his discovery that the Aëdes aegypti mosquito was responsible for yellow fever).

When Stevens resigned in 1907, Roosevelt (who visited the construction in 1906 and was famously photographed wearing a white suit and Panama hat) determined to give the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers complete control of canal construction. He appointed Colonel George W. Goethals (1858–1928) as Chief Engineer. Construction was completed two years ahead of schedule. The first passage, by the French crane-boat, the Alexandre La Valley, was made on January 7, 1914. On August 15, 1914, the canal was formally opened with the passage of the merchant ship, the SS Ancon. More than 5,000 workers died during the decade-long effort, which reduced the sea journey from New York to San Francisco by 9,000 miles.

George Washington Goethals

THE U.S. ERA

The mammoth U.S. presence in Panamá during and after canal construction was an economic godsend for Panamá, which benefited from installation of a modern infrastructure throughout the country. However, a pluralist democracy failed to take root. The next few decades were marked by political instability and corruption among a revolving door of Panamanian leaders. The U.S. invoked its right to intervene in national politics in 1908, 1912, and 1918. Then, on February 8, 1925, the Kuna people revolted, expelled Panamanian officials, and declared independence for their territory along the eastern Caribbean zone of San Blas. The Panamanian government acted forcefully to suppress the revolt, and 22 policemen and 20 tribesmen were killed before U.S. Marines again intervened and the U.S. government brokered a truce. In 1938 the Kuna were granted semi-autonomy of their own comarca (region).

Panamanian society was deeply divided over the U.S. presence, which in 1918 included 14 military bases, complete control of the Canal Zone, and even the overseeing of the Panamanian police force. Governments switched between those in favor and those that considered the U.S. presence a humiliation. In 1927, the Panamanian congress appealed to the League of Nations to abrogate the U.S. right of interference. The following year, President Herbert Hoover (1874–1964) agreed to a Good Neighbor Policy of non-intervention. It was ill timed. In 1931, a radical right-wing nationalist group called Acción Comunal overthrew the government of Florencio Harmodio Arosemena (1872–1945), and the party’s vehemently racist, anti-U.S., and pro-Nazi leader Arnulfo Arias Madrid (1901–88) took power. Arias’ panameñismo (Panamá for Panamanians) philosophy hit a chord with the populace and in 1939 he successfully negotiated the Hull-Alfaro Treaty, which revoked the right of U.S. intervention. Although he established Panamá’s progressive social security system, he ruled by authoritarian means. In 1941, the National Police deposed him. Arias’ overthrow inaugurated a turbulent period in which the militarized police force became arbiters in national politics. Arias was elected by popular mandate on two subsequent occasions (1949–51 and 1968); each time he was deposed by the police. His archenemy was the progressive yet corrupt General José Antonio Remón Cantera (1908–55), an ardent anti-arnulfista who was himself elected to the presidency in 1952 (in 1955, Remón was murdered by machine gun at the Panamá City racetrack).

The rising anti-U.S., pro-Spanish hispanidad movement then sweeping through Latin America caught hold in Panamá. The continued U.S. presence increasingly stung Panamanian pride. In 1947, the pot boiled over when Panamá’s national legislature debated a new treaty that extended the U.S. military’s use of bases outside the Canal Zone. More than 10,000 armed and angry Panamanians stormed the Assembly, and one person died in the mêlée. Understandably, the Assembly voted against the treaty and the following year the U.S. military abandoned some of the bases. Meanwhile, the ensuing decade witnessed increasing clashes between demonstrators (primarily middle-class students) and Remón’s ever more brutal police, which he renamed the National Guard.

In 1951, the U.S. reformed its canal operations. New austerity measures hit hard upon the 10,000 Panamanians employed within the Canal Zone, where U.S. residents enjoyed a privileged life. Relations between the two nations continued to worsen. Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, and Fidel Castro’s communist revolution in Cuba in 1959, added fuel to demands for Panamanian sovereignty over its canal. President Dwight Eisenhower (1890–1969) attempted to mollify growing militancy in Panamá with reforms that included “titular sovereignty” over the canal. It was too little too late. President John F. Kennedy (1917–63) went further under his “Alliance for Progress,” which poured monetary aid into Panamá as a counterweight to the fear of spreading communism. Any goodwill was negated, however, when the U.S. established the School of the Americas within the Canal Zone as an anti-communist training center for military elites from throughout Latin America. (Inevitably, it produced some of the most thuggish military dictators of future years.)

Meanwhile, the right—or lack of it—to fly the Panamanian flag next to the Stars and Stripes within the U.S. Canal Zone had sparked several riots, prompting Kennedy to expand the right to fly the Panamanian flag at non-military sites. When President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–73) proposed reducing the number of Stars and Stripes flown in the Zone, Zonians (U.S. residents of the Canal Zone) protested. On January 9, 1964, students at Balboa High School raised the U.S. flag in defiance of the governor’s orders. This incensed Panamanian students. When students from the Instituto Nacional attempted to raise their flag alongside the Balboa flag, they were prevented by irate Zonians and the Canal Zone police. Angry crowds soon formed. Riots broke out. The police fired into the crowds. And Panamá City erupted. Panamanians of every stripe took to the streets and stormed the Canal Zone fence. U.S. businesses and homes were burned. Bullets flew from both sides and many people were shot in clashes against the U.S. Army’s 193rd Infantry Brigade, which took over defense of the Zone. The Flag Riots continued for several days and left 27 people dead, including an 11-year-old girl, Rosa Elena Landecho, shot by a U.S. Army sniper.

Relations between Panamá and the United States were forever changed. President Johnson stated his willingness to renegotiate the canal treaty.

Panamanian flag

THE DICTATOR DECADES

Arnulfo Arias returned to power in the 1968 presidential elections. However, only 11 days into his term, he was ousted by a National Guard coup, following which Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos Herrera (1929–81) gained power. Torrijos ruled over nominal presidents as actual head of government for the next 21 years. This charismatic and handsome left-winger is fondly remembered as a champion of Panamá’s poor, Spanish-speaking, mixed-blood majority. He initiated a series of progressive socio-economic reforms that expanded health and education, redistributed land to impoverished peasants, and modernized the nation’s infrastructure through massive public works projects. However, Torrijos brutally suppressed political opposition, including censoring the press.

Torrijo’s crowning moment came on September 7, 1977, when he and President Jimmy Carter (1924–) signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty, at Fort Clayton, Panamá (Torrijos was noticeably drunk during the ceremony). Panamanians exulted that the U.S. had agreed to cede gradual control of the canal to Panamá, leading to complete control in December 31, 1999, when all U.S. military bases would also close. (The United States nonetheless retained the right to protect and guarantee the permanent neutrality of the canal.) In an outburst of soberanía—sovereignty fever—the Panamanians adorned the canal administration building with a digital clock, which ticked down the seconds until the Panamá Canal Authority assumed command of the waterway.

Torrijos was killed on July 31, 1981, when his DeHavilland Twin Otter aircraft mysteriously exploded over the Cordillera Central. A series of military figures competed to fill the void. In 1983, National Guard Commander Rubén Darío Paredes stepped down to run for the presidency. Darío handed command of the guard—which had been renamed the Panamanian Defense Forces—to Manuel Antonio Noriega (1934–), a Torrijos protegé with whom Darío had struck a deal. Noriega, however, reneged and seized power for himself. For the next seven years he subjected the country to a brutal reign of corruption, intimidation, and terror while fraudulent elections and puppet presidents maintained a pretense of democracy.

Noriega had been trained at the School of the Americas and had joined the CIA payroll in the early 1970s (CIA director George H. W. Bush authorized an annual payment of $110,000 for Noriega). The U.S. government initially gave tacit support to Noriega (he granted the U.S. expanded military rights in Panamá), despite his involvement with drug trafficking, money laundering, and terror. Disgust with Noriega—nicknamed cara de piña (“pineapple face”) for his pockmarked features—among educated Panamanians crystallized in September 1985, when a political opponent, Dr. Hugo Spadafora (1940–85), was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered while returning to Panamá from exile in Costa Rica. Then, in 1987, Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera (1937–), Noriega’s second-in-command, publicly denounced Noriega, accusing him of drug trafficking and the murders of both Torrijos and Spadafora. Panamá’s middle class launched a Civic Crusade demanding that Noriega step down; their peaceful demonstrations were brutally dispersed by Noriega’s barbarous paramilitary Dignity Battalions. Instead, the dictator declared a state of emergency, suspended constitutional rights, and organized counter-demonstrations by his supporters from the impoverished zambo (non-white) underclass. Noriega’s opponents then called a national strike, paralyzing the nation’s economy.

Statue of Omar Torrijos

Noriega’s handpicked candidate for president, Carlos Duque, was sure to lose the May 1989 elections, as Noriega’s political opponents banded together to support Guillermo Endara Galimany (1936–). Noriega tried to rig the vote, but Duque lost by such a wide margin that he refused to play along with the fraud. Noriega therefore annulled the vote. Former President Jimmy Carter, present as an observer, denounced Noriega for stealing the election. Endara set out to stake his victory with a motorcade through Panamá City. His car was waylaid, however, by Noriega’s pipe-wielding thugs. The world watched, appalled, on television as Endara and his vice president, Guillermo Ford, were beaten bloody.

A Potpourri

The 3.36 million Panamanians are a potpourri—an exotic blend of various shades from white through mulatto to black. Pure “whites” are extremely rare. Almost everyone carries DNA passed down by miscegenation of Spanish (and French) colonialists with Amerindians, African slaves, and English and Dutch pirates during three centuries. Chinese and Indian indentured laborers (imported to work on the Panamá Railroad); Afro-Caribbean laborers and French immigrants (imported to work on the Panamá Canal); American craftsmen, engineers, technicians, military, and administrators (the Zonians); Swiss, German, and Italian farmers who settled the Chiriquí highlands; Hindu and Middle Eastern merchants; and prostitutes from around the globe…all added their unique characteristics to the sancocho stew.

Mixed-blood mestizos officially comprise 70 percent of the population, including moskitos: the mixed offspring of cimarrónes (runaway African slaves) and indigenous Amerindian people, found mostly in Darién province.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE

Panamá’s bouillabaisse is spiced by the nation’s still thriving indigenous cultures: seven distinct tribes display relatively pure bloodlines and together make up almost 10 percent of the Panamá populace. The three largest groups occupy their own comarcas indígenas—semi-autonomous districts that equate to provinces. General Omar Torrijos empathized with the plight of Panamá’s indigenous people; he created an office for indigenous affairs and, in 1972, rewrote the Constitution to give indigenous peoples their own comarcas and political rights.

Most numerous are the Ngöbe-Buglé (165,000), who live primarily in the highlands and foothills of the Bocas del Toro, Chiriquí, and Veraguas provinces. They are also known as the Guaymí and speak their own Ngäbere language. Their comarca, created in 1997, takes up almost one-tenth of Panamá’s territory and was granted after a long (and occasionally violent) campaign to establish their rights. Short of stature, they are easily recognized by the ankle-length dresses (called nagua) of brightly colored fabric edged with zigzag motifs worn by the womenfolk (the men adopt Western fashion). Few Ngöbe-Buglé are assimilated into mainstream Panamanian society, and they are reticent when dealing with “whites”—understandably so given the abuse this once fierce warrior tribe received during five centuries of colonization; and, during the past century, at the hand of cattle ranchers and banana companies, which forced them from their traditional lands. The vast majority live in poverty, practicing slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture or hiring out seasonally for subsistence wages as coffee pickers or plantation workers, including in neighboring Costa Rica. The women make beautiful bags from plant fibers, plus sophisticated hand-beaded bracelets and necklaces (known as chaquira) incorporating sacred motifs of snakes.

Occupying the rain forests of Darién (and extending into Colombia) are 30,000 Emberá-Wounaan tribespeople descended from Amazonian Choco tribes. Their two-part comarca (set up in 1983) takes up much of the northeast and southwest parts of Darién province. Although identical in virtually every other regard, the Emberá (21,000) and Wounaan (9,000) speak distinct tongues. They live in scattered villages along the watercourses, and subsist from fishing, hunting, and slash-and-burn agriculture. Encouraged by the Panamanian government (and no doubt influenced by the brutality imparted by Colombia guerrillas, paramilitaries, and drug traffickers that have infiltrated Darién), only in recent years have these traditionally nomadic people coalesced into permanent villages. Evangelical missionaries have made considerable inroads in recent years, adding to the cultural decay of this proud, friendly, and gentle people. The Emberá-Wounaan traditionally wear, solely, loincloths (for men) or grass skirts (for women); under pressure by evangelists, they are increasingly adopting Western wear. They adorn themselves with necklaces and with tattoos made of the black juice of the tagua nut, which they also carve into lovely animal figurines. Most famously, they have traditionally hunted with blow darts tipped with the deadly toxins of poison-dart frogs. The Emberá-Wounaan are superb carvers of traditional wooden canoes (piraguas), and their exquisitely woven and sewn baskets display inordinate skill—the largest and finest baskets can take an entire year to complete.

The most visually striking and well-known group is the Kuna, numbering around 65,000 concentrated in the Kuna Yala comarca, which incorporates the San Blas archipelago and eastern Caribbean seaboard. See the sidebar The Kuna in the Kuna Yala chapter.

Emberá indigenous family at Playa de Muerto, Panamå