Lobby of Meliá Panamá Canal hotel, Panamá

4

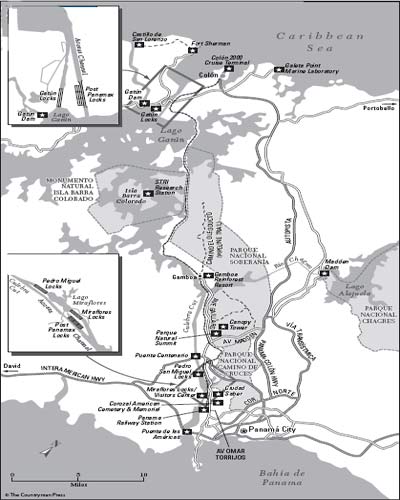

THE CANAL AND COLÓN PROVINCE

“The French had all the will in the world, but it wasn’t enough. The timing was off.”

—DAVID MCCULLOUGH

This region is perhaps the most diverse of any in Panamá. Within its small compass you can cross the isthmus on a boat excursion on the Canal…take a whitewater trip on the Río Chagres…visit an indigenous Emberá village…go birding in Soberanía…hike the ancient Camino Real…revisit the ghosts of pirates past in the fortresses of San Lorenzo and Portobelo…and snorkel or scuba dive amid the Caribbean’s fantastic coral reefs.

Panamá’s main tourist draw, of course, is the Panamá Canal, extending 51 miles (80 km) from Panamá City on the Pacific Ocean to Colón on the Caribbean Sea. A feat of remarkable engineering, it draws thousands of visitors daily to view the passage of cargo vessels, cruise ships, and warships. Viewing is easily done from spectator stands at the Miraflores and Gatún locks, while excursion vessels that set out from Panamá City will take you on a mesmerizing passage through the Goliath locks. To ensure an adequate supply of freshwater, the forested mountains to either side of the Canal have been protected. These lush hinterlands teem with wildlife, easily seen along trails that snake through rugged rain forest enshrined in national parks—Parque Natural Camino de Cruces, Parque Nacional Chagres, and Parque Nacional Soberanía—that together comprise La Ruta Ecológica Entre dos Océanos (the Ecological Route Between Two Oceans), a biological corridor from sea to sea.

The Caribbean coast is steeped in Afro-Antillean culture, reflected in colorful clapboard houses, a spicy cuisine, and rhythmic dances called congos. Colón, at the northern mouth of the Canal, is a melancholic port city that is gateway to Portobelo and Nombre de Dios, fabled treasure ports of the old Spanish Main.

Panamanian girl in Portobelo, Panamá

GETTING THERE AND AROUND

By Bus or Público

UltraCopa (507-314-6248; in Colón, 507-447-1763; $2.50) buses depart the Gran Terminal Nacional de Transporte, beside the Corredor Norte in Albrook, for Colón. Buses for Portobelo depart Colón’s Terminal de Buses hourly (6:30 am–6 pm, $0.50). Additional buses marked “Costa Arriba” depart Colón for Nombre de Dios on the same schedule ($2.50). Note that the turnoff for Portobelo from the Transístmica is by the Supermercado Rey, at Sabanaitas, 8 miles (14 km) before Colón when traveling from Panamá City; you can catch the Colón-Portobelo bus in Sabana Grande.

By Car

Carretera Gaillard (officially Avenida Omar Torrijos Herrera) leads north from Ancón and parallels the Canal on its eastern side, granting access to Miraflores Locks, Pedro Miguel Locks, and ending at Gamboa. This road also delivers you to Parque Nacional Camino de Cruces and Parque Nacional Soberanía. It also links with the Transístmica (Carretera 2), the main highway linking Panamá City and Colón, on the Caribbean coast. From Colón, Carretera 31 runs east along the Caribbean shore to Portobelo and Nombre de Dios; and Carretera 32 runs west to the Gatún Locks and, beyond, to Parque Nacional San Lorenzo and along the northern shores of Lago Gatún.

By Ship

You can transit the canal aboard cruise ships that include it on their itineraries. The passage is also a highlight of eight-day “Costa Rica and the Panamá Canal” cruise-tours offered by National Geographic Expeditions (888-966-8687; www.nationalgeographicexpeditions.com), December through May; and similar itineraries by Cruise West (888-851-8133; www.cruisewest.com), October through March. I typically escort two or more cruise-tours annually for National Geographic Expeditions. Please join me! Dates are listed on my Web site: www.christopherbaker.com.

In Colón, most cruise ships dock at the modern Colón 2000 (507-447-3197; www.colon2000.com; Calle El Paseo Gorgas) cruise port. Taxis are available for exploring. A few smaller ships berth at Muelle Cristóbal, near the commercial docks on the opposite side of the city.

By Train

There’s no doubt that the best way to travel between the coasts is aboard a train operated by the Panamá Railway Company (507-317-6070; www.panarail.com; $22 adults, $15 seniors, $11 children, each way). The train departs Panamá City’s Estación de Corazol, in Albrook, for Colón Monday through Friday 7:15 AM; the return train departs Colón at 5:15 PM. Choose from one of five historic wood-paneled coaches or the dome car, with a glass roof. You’ll be in view of the Canal and Lago Gatún for virtually the entire way, including a long section that plays hopscotch across bridges that link several isles in the lake. Reservations are not required.

Tour operators offer guided excursions that include train transfers.

By Tours

Most tour operators in Panamá City offer daylong excursions to the Canal, the various national parks, plus Portobelo. Two to consider are Ancón Expeditions (507-269-9415; www.anconexpeditions.com) and Panamá Travel Experts (507-6671-7923; www.panamatravelexperts.com).

The most thrilling experience of all—a must-do!—is a small boat excursion through the locks. Three companies offer day trips from Panamá City. Canal and Bay Tours (507-290-2009; www.canalandbaytours.com) has trips aboard the 400-passenger Fantasia del Mar and Tuira II and the Prohibition-era Isla Morada, departing on Saturday from Balboa. Panamá Marine (507-226-8917, www.pmatours.net) offers partial and full-transit trips aboard the Pacific Queen every Saturday from Flamenco Marina. Panamá Yacht Tours (507-263-5044; www.panamayachtours.com) also departs Flamenco Marina and uses smaller vessels for a more intimate experience. All three companies charge about the same: $115 adult, $60 child, partial transit; $165 adult, $75 child, full transit.

Colón 2000 cruiseport sign, Panamá

The Canal Zone

The term, the Canal Zone, is politically incorrect in current-day Panamá, where it denotes, to them, the imperialistic U.S.-owned and run 10-mile zone to either side of the Canal during Uncle Sam’s tenure (1907–1999). With apologies to Panamanians, I use it here with a small “c” and small “z” to encompass the same 2,134-square-mile (552,761 ha) zone administered by the Panamá Canal Authority (Autoridad del Canal de Panamá or ACP; 507-272-1111; www.pancanal.com/eng/index.html) since Panamá gained jurisdiction of the former Canal Zone on December 31, 1999.

For information on Gatún Locks, see the Colón section.

LODGING

AVALON GRAND PANAMA RESORT

800-261-5014

www.avalonvacations.com

Vía Transístmica, Las Cumbres

Moderate

Seemingly at odds with its surroundings, this towering 171-room resort hotel sits on a hill at the edge of Parque Nacional Camino de Cruces. It aims directly at local families with its waterpark. But the huge rooms are tastefully furnished in sober fashion, with tile floors and king beds. Families can opt for any of 41 casitas with kitchenettes.

Panamá Canal

CANOPY TOWER ECOLODGE AND NATURE OBSERVATORY

506-264-5720 or 800-930-3397

www.canopytower.com

Semaphore Hill Road, Parque Nacional

Soberanía

Moderate to Expensive

The place par excellence for serious birders, this world-renowned lodge in the thick of Parque Nacional Soberanía is unique in many ways. Start with the octagonal architecture: it used to be a radar tower and still has that hollow warehouse feel, thanks to bare metal walls and beams. First-story rooms are Spartan, share bathrooms, and are a tad pricey. Better by far are the larger more pleasantly furnished, pie-slice-shaped upper-level rooms. Warning: some look out over the parking lot. The rooftop observation platform is a boon for birding. Guests (and day visitors) are offered a range of guided birding options, including aboard modified observation vehicles.

GAMBOA RAINFOREST RESORT

507-206-888 or 877-800-1690

www.gamboaresort.com

Gamboa

Expensive

Truly a resort in the rain forest, this is a perfect base for travelers seeking plenty of comfort and company. Its setting is stunning, with gorgeous views over the vast swimming pool complex toward the Río Chagres and nearby rain forests. Stylish and modern, it has heaps of facilities, including a spa, choice of restaurants and bars, plus organized and self-guided nature activities. The 107 rooms are spacious and pleasingly furnished, and all come with TV, telephone, and balcony with view. Suites have king beds. Families might opt for one of 48 apartments in renovated 1930s Panamá Canal Administration homes.

HOSTAL CASA DE CAMPO COUNTRY INN AND SPA

507-226-0274

www.panamacasadecampo.com

Cerro Azúl, 28 miles (40 km) east of Panamá City

Moderate

This exquisite bed-and-breakfast hotel, close to the eastern entrance to Parque Nacional Chagre, makes a perfect resting place for hikers and birders (guided tours are offered). The owners have decorated the 11 bedrooms in richly colored, old-world fashion, with deep ocher and sienna, and a combination of wicker and antique furniture. It has a spa and swimming pool, and serves home-cooked meals.

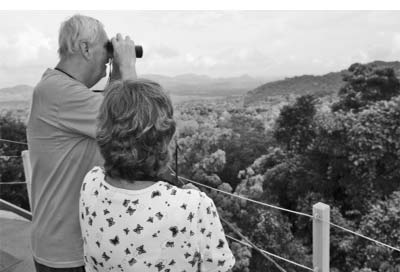

Couple with binoculars atop Canopy Tower, Panamá

HOSTEL LA POSADA DE FERHISSE

507-297-0197

laposadaferhisse@hotmail.com

Calle Domingo Díaz, Cerro Azúl

Inexpensive

For budget travelers. Close to the Parque Nacional Chagres’ Cerro Azúl entrance. It has tremendous lake and mountain views, The six accommodations are comfortable but somewhat basic. A high point is the restaurant serving tasty local fare.

PANAMA CANAL FLOATING LODGE

507-832-7679, or 954-678-9990 in North

America www.gatunexplorer.com/panama-canal-floating-lodge.html

Lago Gatún

That’s right. Anchored in a cove on Lago Gatún, this rustic two-story wooden houseboat is a terrific, albeit rustic one-of-a-kind experience. It has hammocks on private balconies accessible through screened walls that let in the sounds of screeching monkeys and birds—perfect! Meals are served family-style, alfresco.

SIERRA LLORONA

507-442-8104

www.sierrallorona.com

2.8 miles (4 km) north of Sabanita, 9 miles (15 km) southeast of Colón

Inexpensive to Moderate

This contemporary-styled hotel operates as a “jungle lodge” and is particularly popular with birders and nature lovers keen to spot the region’s wealth of wildlife. It sits atop a hill overlooking a 494-acre (200 ha) rain forest reserve laced with trails and observation platforms. It offers pre-dawn birding tours, and a range of nature tours and activities. The eight cross-ventilated rooms and suite (with Jacuzzi) are a delight, being simply yet tastefully furnished. Each has shuttered, screened windows, plus ceiling fans. Buffet meals are served and it has Internet and a bar. In driving here in wet season, you’ll need a 4WD vehicle.

It also has camping facilities with rustic stoves and barbecue pits.

DINING

TOP DECK

507-276-8325

www.pancanal.com

Miraflores Locks Visitor Center, Avenida

Omar Torrijos Herrera, 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Albrook Daily, noon–11

The Miraflores Locks can hold your interest for hours. Fear not when hunger strikes, as the top-floor buffet restaurant is first class. You can dine outside on a shaded terrace overlooking the action. For lighter fare, opt for the ground floor snack bar, selling salads, sandwiches etc.

ATTRACTIONS, PARKS, AND RECREATION

CANOPY TOWER ECOLODGE AND NATURE OBSERVATORY

506-264-5720 or 800-930-3397

www.canopytower.com

Semaphore Hill Road

Atop a hill in the midst of Parque Nacional Soberanía, this world-famous ecolodge is one of the premier birding sites in the nation. The 12-sided metal tower began life as a U.S. military radar station that pokes above the tropical moist forest canopy. It’s not typically open to day visits by your average Joe, but serious birders are usually welcome. It has binoculars and scopes for jaw-dropping vistas from the rooftop. The mile-long access road, Semaphore Hill Road, from the Gaillard Highway offers tremendous birding, particularly of species that live close to the forest floor, such as antbirds, as well as raptors. And mammals such as agoutis (ñeques), coatis, and howler monkeys, and Geoffrey’s tamarin are frequently seen. I highly recommend that you overnight.

Canal Factoids

The failed French effort to build a canal (1879-89) claimed at least 20,000 lives.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers oversaw construction (1906–14), which cost $352,000,000.

When completed in 1914, the Panamá Canal was the grandest and most costly human enterprise ever conceived.

5,609 workers died of accidents and disease during U.S. construction (1906–14), averaging about 500 lives per mile.

The canal connects the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean and runs northwest to southeast.

The canal is 50 miles (80 km) long from ocean to ocean.

The canal cuts through the narrowest and lowest saddle in Central America.

56,307 people were employed during construction (1904–14), of which 31,071 were from the West Indies.

The canal has three sets of locks, each with twin chambers side by side; there are 12 chambers in total.

Each chamber is 110 feet (33.5 m) wide by 1,000 feet (305 m) long—the dimensions were intended to accommodate the largest battleships of the day. They average 85 feet (26 m) deep.

The largest vessels allowed are called Panamax ships; they measure 106 feet (32.3 m) wide by 965 feet (294.1 m) long.

There are 46 paired and mitered lock gates, each measuring 65 feet (20 m) wide and 7 feet (2 m) deep. The gates vary in height from 47 to 82 feet (14 to 25 m), depending on their location, with Miraflores having the tallest gates.

The hollow gates float at near negative buoyancy; they are so finely balanced that a single 19-kilowatt electric motor was sufficient to open and close them (a hydraulic system was introduced in 1998).

All upper chambers have double layers of gates to prevent flooding in the event that the first pair is breached.

It takes 52 million gallons (101,000 cubic meters) of fresh water to fill a lock chamber, which can be filled in eight minutes.

The canal accounts for about 60 percent of Panamá’s fresh water consumption.

The canal has operated 24/7 only since 1963, when lighting was installed.

Vessels normally pass through both lock chambers in the same direction. Northbound ships transit between midnight and noon; southbound ships transit between noon and midnight. There is a brief period when ships pass in opposite directions.

A typical passage through the canal takes approximately 8–10 hours.

Ships sailing from New York to San Francisco via the canal travel 6,000 miles (9,500 km); the same journey via Cape Horn would require a 14,000-mile (22,500 km) passage.

About 14,000 vessels transit the canal every year, representing about 5 percent of the world’s sea traffic.

Tolls are based on vessel type and size, and the type of cargo carried. The most expensive toll charged to date was US$331,200, paid on May 16, 2009, by the Disney Pearl.

The lowest toll for passage was 36 cents, paid by Richard Halliburton, who swam the canal in 1928.

CIUDAD DEL SABER

507-317-0111

www.ciudaddelsaber.org

Clayton, 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Balboa Monday through Friday 8–5

In 1999, the U.S. military handed the former Fort Clayton U.S. Army base to the nation, which turned it into The City of Knowledge. Spanning 297 acres (120 ha), the facility hosts various local and international research organizations, including high-tech companies zoned in the Tecnoparque Internacional de Panamá. Dozens of prestigious entities are based here, including the Organization of American States, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and World Wildlife Fund.

The main draw for visitors is the Fondo Peregrino Panamá (Peregrine Fund of Panamá 507-317-0350; www.fondoperegrino.org; Calle Arnoldo Cano, Casa 87, Ciudad del Saber), alias the Neotropical Raptor Center. It breeds harpy eagles for reintroduction into the wild. Call to arrange a visit and to hold a “tame” harpy eagle.

The SACA bus ($0.35) for Clayton departs from beside the Plaza Legislativa, in Panamá City. Taxi Clayton (507-317-0386) operates from the Ciudad del Saber.

COROZAL AMERICAN CEMETERY AND MEMORIAL

507-207-7000

www.abmc.gov/cemeteries/cemeteries/cz.php

abmcpan1@cwpanama.net

Calle Rynicki, off Avenida Omar Torrijos Herrera, Clayton

Panamá Canal pilot boat with Ciudad del Saber behind, Panamá

Daily 9–5, closed December 25 and January 1

This 16-acre military cemetery is under the care of the American Battle Monuments Commission. More than 5,360 U.S. veterans and civilians associated with Canal construction and/or operation are interred here; the oldest grave dates back to 1790. From the Visitors Center, a paved path leads uphill to a small memorial with a rectangular granite obelisk flanked by twin flagpoles flying the U.S. and Panamanian flags.

Gamboa

Gaillard Highway, 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Panamá City. This small community, at the end of the canal road at the mouth of the Río Chagres and at the entrance to the Gaillard Cut, was founded in the 1930s by the Panamá Canal Company to house its Canal Maintenance Division. Originally staffed by U.S. personnel, the community’s clapboard architecture is quintessential yanqui colonial vernacular. The main sightseeing draws, besides passing ships, are two mammoth floating cranes that are used to haul bulky objects such the 945-ton lock gates. Hercules (built in 1914) and Titan (1941) were made in Germany.

Pipeline Road, considered Panamá’s preeminent birding trail, begins where the paved road ends and snakes into Parque Nacional Soberanía. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Gamboa Field Station (507-212-8082; www.stri.org) is a center for biological research in the park, but is not open to casual visitors. The dock for Barra del Colorado Island is here.

The SACA (507-212-3420) bus departs from in front of the Palacio Legislativo at Plaza Cinco de Mayo.

GAMBOA RAINFOREST RESORT

507-314-5000

www.gamboaresort.com

Gaillard Highway

You don’t have to overnight here to participate in the wide range of activities that lure visitors to this luxury hotel and nature-themed adventure center with a scenic setting overlooking the Chagres river. Day visitors are welcome. It offers guided birding hikes as well as an easy 1-mile (1.6 km) self-guided trail. An interpretative park educates you on various local ecosystems, such as the lowland tropical forest. And it has a live butterfly exhibit and nursery; an orchid nursery; and a serpentarium displaying many endemic snake species, from the beautiful finger-thin vine snake to the deadly fer-de-lance. Plus, if you don’t make it out to the real Emberá village, it has a faux facility here.

Other options include:

Aerial Tram: You can ride in an open cage on a ski-lift-style tram that ascends 367 feet (112 m) through the rain forest. You won’t see much wildlife, although the guides assigned to each cage give interesting ecological briefings. At the top, you can climb a 90-foot (27.4 m) mirador—lookout tower—for spectacular bird’s eye views over the rain forest, Río Chagres, and Gaillard Cut. Departs Tuesday through Sunday 9:15 AM, 10:30 AM, 1:30 PM, 3:00 PM; $50.

Vine snake

Boat and Kayaking Tours: Options include a guided boat tour of Lago Gatún, with an emphasis on wildlife viewing (six tours daily; $35); and a 40-minute tour on the Río Chagres ($15). And who would have thought you could actually kayak on the Canal (three-hours; by demand; $50).

Safari Night: One of my faves is a nocturnal one-hour “Safari Night” tour in search of all the critters that are active after dark. Fascinating! Daily at 7 PM; $40.

Lago Gatún

Sprawling over 166 square miles (423 sq km), this freshwater lake was formed by damming the Río Chagres near the river’s mouth at Gatún. The dam was completed in 1910 and it took four years for the lake to fill, forming what was then the largest man-made lake in the world. Dozens of small villages were inundated, as was much of the Panamá Railroad, which was relaid on higher ground. The lake’s surface is 85 feet (26 m) above sea level; it is being deepened as part of the Canal expansion. The lake spans half the isthmus; it features lushly clad isles. Along its fringes dead trees protrude like clawing fingers.

Don’t swim in the lake. There are crocodiles! The croc population has expanded considerably in recent years, not least in thanks to an abundant supply of peacock bass (sargento). Anglers are in their element. Panamá Fishing and Catching (507-6622-0212; www.panamafishingandcatching.com) offers fishing tours.

Many of the commercial concessionaires with businesses on the lake have been forced to close in recent years by the ACP. Nonetheless, you can still explore by boat.

Gatun Explorer (507-832-7679; www.gatunexplorer.com) offers a variety of lake tours by canopied motorboat and also by kayak—a great way to get close to anhingas, caimans, monkeys, and sloths. It also has fishing trips. Excursions depart the dock in Gamboa.

Notwithstanding the presence of crocs, Scubapanama (507-261-3841; www.scubapanama.com) offers experienced divers a chance to explore a century-old train that lies 52 feet (30 m) down in the murky waters.

MIRAFLORES LOCKS

507-276-8325

www.pancanal.com cvm@pancanal.com

Avenida Omar Torrijos Herrera, 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Albrook Daily 9–4:30 (ticket office); 9–5 museum Admission: $8 adults, $5 students, and children (free under 5 years of age) The most impressive of the three esclusas (locks) by virtue of the superb viewing gallery and museum, this southernmost lock system is a mere 16 miles (25 km) from the city center. No wonder it’s Panamá’s number one tourist attraction!

Miraflores has two flights that together with the approach channel stretch for 1.1 miles (1.7 km), linking the Pacific Ocean with Miraflores Lake. Because the Pacific tidal variation is far more extreme than that of the Caribbean Sea, the chambers here are deeper than at Pedro Miguel and Gatún, providing a lift varying between 43 feet (13.1 m) and 64.5 feet (19.7 m), depending on the state of the tide. (The lift is fixed at 31 feet/9.45 m at Pedro Miguel, and 85 feet/25.9 m at Gatún.). The steel lock gates here are, logically, also the largest of the three locks and weigh 945 tons apiece. Each transit takes about 10 minutes from the time a vessel enters a chamber. Since there are four chambers here, two in each direction, as many as four Panamax vessels—the maximum size permitted—might be transiting at any one time.

You’ll get a grandstand view—literally—from the four-story Visitor Center (Centro de Visitantes; www.pancanal.com/eng/anuncios/cvm/index.html), built opposite the control tower and with viewing platforms on each level for an intimate close-to-the-action perspective as cruise ships and supertankers ease past almost within fingertip reach. Bilingual commentators broadcast running commentaries on the operation of the locks and the specifics about each vessel transiting.

Visitor center at Miraflores Locks, Panamá Canal

Exhibitions: The center has four state-of-the-art exhibition halls with superb presentations that include video presentations, interactive displays, models, and dioramas themed by floor. The History Hall, on the ground floor, profiles the Canal’s conception and construction. The second floor Hall of Water educates about the watershed and the role that conservation plays in ensuring the Canal’s operation. Above, The Canal in Action takes you inside a culvert and a full-scale pilot-training simulator, while a topographical scale model demonstrates a virtual ocean-to-ocean transit. The fourth floor profiles the Canal’s role in world trade. Movies are sometimes shown in a 182-seat theater.

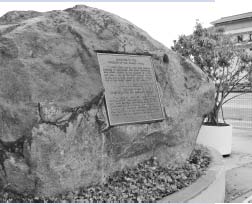

Before entering the Center, note the Belgian locomotive near the base of the steps. It was used to haul excavated material to Amador and was restored after being raised from Gatun Lake in 2000. And exit the Center on the canal side to view the Culebra Cut Rock, a giant rock inset with a plaque quoting Theodore Roosevelt. It is dedicated TO THE BUILDERS OF THE CANAL.

Getting There: Buses marked Gamboa, Paraíso, and Summit Gardens depart the Gran Terminal Nacional de Transporte, in Albrook. Choose the air-conditioned buses departing 4–7 AM and 2–3:30 PM, as they drop off at the gates to Miraflores. Buses at other times drop you at a stop on the highway, a 10-minute walk away.

A taxi from downtown will cost about $15 one-way.

MONUMENTO NATURAL ISLA BARRO COLORADO

507-212-8026 or 212-8951 reservations

www.stri.org

Lago Gatún

Boat departures from Gamboa: 7:15 AM

Monday through Friday, 8 AM Saturday and Sunday

The 13,800-acre (5,600 ha) Barro Colorado Nature Monument (BCNM) comprises 4,200-acre (1,500 ha) Isla Barra Colorado and five surrounding mainland peninsulas on the southern shores of Lago Gatún. The biological reserve was created in 1923 as a scientific research base for the study of tropical ecosystems. It has been managed since 1946 by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI).

How the Canal Operates

A SHIP’S PASSAGE

Ships transiting from the Caribbean to the Pacific enter the Canal channel via the Bay of Limón. They then sail 6.2 miles (10 km) to Gatún Locks, which raises the ships 85 feet (26 m) in a three-step lock system. Ships then enter Gatún Lake and sail 23 miles (37.8 km) across the lake—they follow the course of the now-submerged riverbed (the deepest part of the lake)—to enter the Gaillard Cut. This 8.5-mile-long (13.7 km) man-made canyon cuts through the continental divide and is named for Colonel David Gaillard, the engineer in charge of excavation. Ships then arrive at Pedro Miguel, a single-step lock that lowers vessels 31 feet (9.5 m) to Miraflores Lake. A 1-mile (1.6 km) passage across this narrow lake brings vessels to the two-step Miraflores Locks, which lowers them to the level of the Pacific Ocean (the drop varies according to tidal conditions).

All captains (even of military vessels) must relinquish control of their vessel to an ACP pilot for the transit. Ships are guided through the channels and lake by navigational markers. After entering the lock channels, ships are tethered on each side—front and rear—to electric locomotives called mulas (mules). These run along tracks parallel to the chambers and serve merely to keep the ships aligned; the vessels move under their own propulsion.

Mula at Miraflores Locks, Panamá Canal

HOW IT FUNCTIONS

The Canal has operated without a hitch around-the-clock for almost a century—a testament to its genius of simple design and flawless construction. Its operation relies entirely upon a constant flow of fresh water moving under the force of gravity from Lakes Gatún and Miraflores. The lakes are supplied by water draining in off the surrounding rain forest-clad mountains, principally from the Río Chagres. The entire lock operation was designed to function electrically, with a water spillway and HEP station at Gatún generating the power for the system’s 1,500 electric motors. (The system uses only 25 percent of the hydroelectric power produced; the rest is sold to the national grid.)

Plaque memorial to Major David Gaillard, Miraflores, Panamá

Water from the lakes also fills the upper chambers and flows from one chamber to the next or to the sea-level channels to raise and lower ships. No pumps are used. Water pours into each chamber via three 22-foot-wide (7 m) culverts: one to each of the massive concrete side walls and a third in the center wall that divides the chambers. The flow of water is controlled by valves at each end of the culverts, which slide up and down, like windows, on roller bearings. To flood a chamber, valves at the upper end are opened while those at the lower end are closed. Water feeds from each of the main culverts via 10 perpendicular cross culverts (thus, 20 cross culverts per chamber) that run beneath the chambers. Each cross culvert has seven vertical culverts evenly distributed across the chamber floor to minimize turbulence as water boils up under pressure to fill the chamber. The upper valves are closed once the chamber fills. To empty a chamber, the valves at the lower end are opened and gravity does the rest.

Until recently, a locomotive drive-wheel principle was employed to open and close the massive steel gates: A connecting rod affixed to the center of each gate leaf attached at its other end to the outer circumference of a massive horizontal “bull wheel” within the side walls. The wheels were powered by an electric motor as they revolved through 200 degrees. Today, a hydraulic system is employed.

The valves, lock gates, and mulas are controlled from a control room, much like an airport control tower, atop the center wall of each set of locks. Today a state-of-the-art computerized hydraulic system using fiber-optic cable has replaced the original electro-mechanical system. (Originally, each control room featured a central control board that was a working scale replica of the locks, with manual switches next to each representation of valves, gates, and other moving components, which mirrored the exact state of the actual lock components in real time. To guard against error, the switches were all linked mechanically and necessitated being operated in correct sequence to function.)

Gaillard Cut rock dedicated to memory of Panamá Canal workers, Miraflores, Panamá

Barro Colorado is the largest island in the Panamá Canal waterway. It is fringed by marshy grasslands and mangroves, while inland comprises primary lowland tropical moist forest. Wildlife abounds. Imagine more than 200 ant species! And almost 400 species of birds. Plus, its more than 120 mammal species—of which 72 are bat species—include agoutis, coatis, sloths, and 5 monkey species: howler, spider, white-faced, Geoffrey’s tamarin, and night monkey. Ocelot, peccaries, and tapirs are also present, though rarely seen by visitors. And jaguars occasionally visit by swimming from the mainland!

National Geographic Expeditions passengers birding at Barra Colorado Island, Panamá

Day visitors are welcome by prior request (reserve well in advance). If approved by STRI, your trip includes boat transfers (departing Gamboa Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday at 7:15 AM, Saturday and Sunday at 8 AM; $70 adult, $40 student), plus a guided three-hour hike and lunch. The Field Research Station has a small visitor center. The laboratories are off-limits to visitors. And only a single 1.5-mile (2.4 km) nature trail is accessible to the public; another 34 miles (56 km) is restricted to scientists. No children under 10.

Some local tour operators offer excursions. And the island is included, uniquely, on National Geographic Expeditions’ “Costa Rica and the Panama Canal” cruise-tours (888-966-8687; www.nationalgeographicexpeditions.com).

PARQUE MUNICIPAL SUMMIT

507-232-4854

www.summitpanama.org

Gaillard Highway

Daily 9–5

Admission: $1 adult, free to children 11 and under

Managed by the city municipality, Summit Nature Park (formerly Summit Botanical Gardens and Zoo) is a gem. It’s the closest thing that you’ll find to a zoo in Panamá, and gives a taste of some of the critters you may (or may not) see in the wild, such as tapir, ocelot, peccaries, and the harpy eagle. In fact, this well-maintained facility breeds harpy eagles in huge enclosures that permit these massive birds to fly. It also has a primate enclosure, a crocodile corner, and even “Jaguar World”—reason enough to visit. Summit was established in 1923 as an experimental farm for introduced species; today it is Panamá’s national botanical garden, boasting more than 150 species of palms, shrubs, and trees from around the world. Bring the kids and make a picnic of it.

PARQUE NACIONAL CAMINO DE CRUCES

507-229-7885

www.anam.gob.pa

Avenida Omar Torrijos Herrera

Daily 9–5

Admission: Free

Wedged between Parque Natural

Metropolitano (to the south) and Parque Nacional Soberanía (to the north), this park is part of the Canal watershed and protects 18 square miles (4,590 ha) of moist forest and, like its neighbors, is a great place for birding and for spotting such mammals as agoutis, coatis, and Geoffrey’s tamarin. You can explore along the park’s namesake historic treasure trail—the Path of the Crosses—that once linked Panamá City with the Chagres River prior to construction of the Camino Real (which linked to Portobelo). The path is only partially excavated, and the roots of giant ceiba and fig trees snake along the forest floor. Robberies have occurred in past years. Don’t hike alone!

PARQUE NACIONAL CHAGRES

507-232-7228 or 229-7885

www.anam.gob.pa

Transístmica, Km 40

Daily 8–5

Admission: $3

Enshrining 500 square miles (129,585 ha) of lowland and montane rain forest east of the Transístmica highway, this massive park was created in 1985 to protect the watershed of the Río Chagres basin—the main water source for Panamá City and the Canal. Before construction of the Canal, the mighty river flowed unimpeded into the Caribbean and was a major impediment to the French effort to dig a canal. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, however, had the foresight to dam the river to create Gatún Lake and channel the flow. In 1934, they completed Madden Dam to create a second lake—Lago Alajuela (previously Madden Lake)—upstream. The lake is good for fishing.

The park spans four different life zones, with elevations ranging from a mere 197 feet (60 m) above sea level to 3,003 feet (1,007 m) atop Cerro Jefe, where stunted elfin forest is draped in frequent mists. This peak, and neighboring Cerro Azul (2,529 feet/771 m), are in the southeast of the park and are accessed from the Interamerican Highway, about 24 miles (38 km) east of Panamá City; you’ll need a 4WD vehicle. They’re popular destinations for birders and Indiana Jones-style hikers. The Cerro Azúl ranger station permits camping.

Birding and wildlife viewing are major draws: The park boasts more than 500 bird species. Watch for harpy eagles soaring overhead on the lookout for monkeys or sloths to scoop up from the branches of towering cedro and mahogany trees. Wildlife is also encyclopedic. Monkeys are a dime a dozen. Ocelots and jaguars prowl the forests. Capybaras wallow in the swampy lagoons and grasslands. And crocodiles and otters splash around in the rivers.

The park is named for the Indian cacique (chief) who ruled the area at the time of the conquistadores. Fittingly, two indigenous communities still thrive here on the northern shores of Lago Alajuela (they were actually moved here three decades ago after being displaced by flooding during creation of Lago Bayano, in Darién). Visitors to Comunidad Emberá Parará Púru and the more distant and much less visited Emberá Drua (507-333-2850 or 6709-1233, www.trail2.com/embera/tourism.htm) are welcomed with ceremonial dances and demonstrations of traditional Emberá lifestyle. Motorized dugout canoes ($25) will take you to Parará Púru from the lake-side village of Nuevo Vigia; the Panamá City-Colón bus will drop you off at Km 29, from where it’s about 2 miles (3 km) to Nuevo Vigia. You’ll need a 4WD vehicle to reach Drua via the remote dock of Corotú, where you can take a water taxi (about 45 minutes); see the community Web site for directions. Tour companies such as Aventuras Panamá (507-260-0044; www.aventuraspanama.com) and Ancón Expeditions (507-269-9415; www.anconexpeditions.com) offer excursions. However, for a more intimate experience, I recommend Embera Village Tours (506-6758-7600; www.emberavillagetours.com), run by gringa Anne Gordon, whose husband is a member of the Púru. You can overnight in Púru—a very humble experience, as the community has no electricity, and “running water” means a boy with a bucket.

The Canal Expansion Project

After Panamá gained control of operations in 1999, the ACP invested more than $1 billion to widen, straighten, and modernize the canal, resulting in a 20 percent decrease in transit time and a corresponding increase in shipping volume. Nonetheless, with some 14,000 vessels a year now transiting, the canal is operating at about 95 percent of its potential capacity and is expected to max out by 2012. Moreover, the canal is unable to handle the Goliath “post-Panamax” ships that exceed the current chambers’ dimensions. Thus, the Panamá Canal has been losing market share to the Suez Canal.

A national referendum in October 2006 approved the ACP’s ambitious decade-long ampliación (expansion) plan for construction of a parallel and entirely separate canal and lock system capable of handling “post-Panamax” vessels. The $5.2-billion project, prepared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, consists of the construction of two new sets of locks: one each at the Pacific and Caribbean sides. Each lock will have three chambers measuring 1,400 feet/427 m long by 180 feet/55 m wide by 60 feet/18.3 m deep apiece. Each chamber will be fed from three tiered reservoirs that will recycle the water used. To guarantee sufficient water, the navigation channels are being widened and deepened, and Gatun Lake is also being deepened to increase water depth sufficient for approximately 1,100 additional transits per year. New navigational channels are also being cut.

Fortunately, much of the work had been completed five decades ago. The U.S. Army began cutting its own third set of locks in 1939, but the project was suspended in 1942 when the U.S. entered World War II. The new locks, which will employ rolling gates rather than miter gates, will use a significant portion of these earlier excavations. The project is expected to be completed by 2015.

Aventuras Panamá also specializes in one- and two-day whitewater rafting trips on the upper Chagres—a thrilling escapade and escape within an hour or two of Panamá City. And Ancón Expeditions offers guided hikes along the centuries-old camino real treasure trail, a partially overgrown and extremely rugged trail that winds through the valleys of the Boquerón and Nombre Azul rivers. You can hike all the way to Nombre de Dios and Portobelo (allow two to three days). Do not hike this trail alone!

PARQUE NACIONAL SOBERANÍA

507-232-4291 or 229-7885

www.anam.gob.pa

Avenida Omar Torrijos Herrera, 15.5 miles (25 km) NW of Panamá City

Daily 8–5

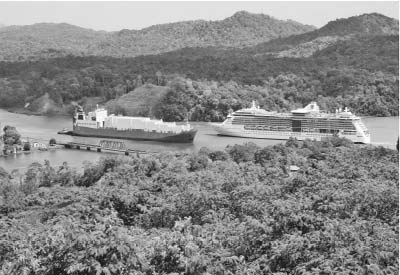

Cruise ship and freighter passing in the Gaillard Cut, Panamá Canal

Admission: $3, but the fee is rarely collected

Part of the Canal Zone watershed, this easily accessible park was created in 1980 to protect a 54,597-acre (22,104 ha) swath of lowland rain forest extending inland from the eastern shores of Lago Gatún and the Gaillard Cut and rising to 279 feet (85 m) atop Cerro Calabaza. The dense forest includes massive mahoganies, silk cotton trees, and strangler figs whose crowns form a canopy. It teems with 55 amphibian, 79 reptile, and more than 100 mammal species, including anteater, coatimundis, sloths, tapir, and monkeys such as Geoffrey’s tamarin. Soberanía is particularly renowned for superb birding, including the chance to spy bicolored, ocellated, and white-bellied antbirds, and even harpy eagles. In fact, more species of birds have been sighted in a single day—360, set by the Audubon Society in 1996—than anywhere else on earth, along the broad, 10-mile (16 km) Pipeline Road, or Camino del Oleoducto. Many early morning hikers report seeing capybaras (the world’s largest rodents) in the bogs near the trailhead just outside Gamboa village. Camino del Plantación (Plantation Road, 4 miles/6.4 km) is also great for birding.

The trails are all well signed, including the short Sendero El Charco (2.5 miles/4 km), which begins roadside about 1.2 miles (2 km) beyond the Summit Botanical Garden. It leads to a waterfall with a pool good for refreshing dips. You’ll forever remember a hike along the Sendero Las Cruces, a remnant of the 16th-century Camino de Cruces treasure trail, with slippery cobbles underfoot; note the hoof marks etched by mules centuries ago. It extends for about 6.5 miles (10 km) to the banks of the Río Chagres. Here, indigenous members of the Comunidad Wounaan San Antonio (507-6706-3031; www.authenticpanama.com/wounan.htm) have lived lake-side since 1958 and today welcome visitors, as does the nearby Comunidad Emberá Ella Purú.

Recent years have witnessed a series of robberies on the trails. Ask the rangers at the ANAM office at the park entrance about current conditions, or book an excursion to Soberanía with a local tour company.

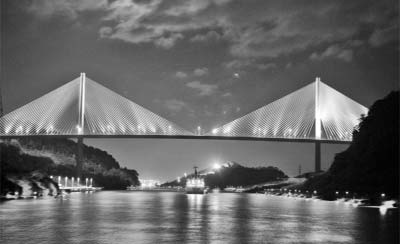

PUENTE CENTENARIO

Opened in 2004, the twin-towered Centennial Bridge spans the Canal at the southern entrance to the Gaillard Cut. It links Panamá City to the town of Arraiján and today carries the Interamerican Highway. The graceful 3,451-foot (1,052 m) bridge is strung like a harp. The roadway clears the canal by 262 feet (80 m), allowing even the largest vessels to pass beneath. It is illuminated at night and is best admired from vessels on the Canal.

Centennial Bridge over Panamá Canal by moonlight

SHOPPING

It always pays dividends to buy from the source, for both buyer and seller. Buying tagua-nut carvings, woven baskets, carved gourds, and bead jewelry is a bonus of any visit to Comunidad Emberá Parará Púru, Emberá Drua, and Emberá Púru, in Parque Nacional Chagres.

For quality crafts and Canal memorabilia, you can’t beat the gift shop in the Miraflores Locks Visitor Center, at Miraflores Locks.

Colón

To many visitors, this could well be the very definition of a sultry down-at-heels tropical port. The nation’s second largest city (population 45,000), at the northern entry to the Panamá Canal, owes its creation in 1850 to construction of the Panamá Railroad to serve argonauts en route to and from the California Gold Rush. (Colón was the Colombian government’s name for the town; the yanquis called it Aspinwall, after William Henry Aspinwall, the railroad’s founder.) Originally it occupied Isla Manzanillo, in the Bahía de Limón, and was linked to the mainland by a causeway. In ensuing years the watery land between them was filled in and the city expanded: In 1948 the Manzanillo area became a Free Trade Zone—the current lifeblood of the city, along with income from the still-active port.

Much of the town perished in a conflagration on March 31, 1885, during the Colombian civil war. Still, enough centenary structures remain to make this of at least marginal interest for sightseeing. And city fathers have invested considerable money in recent years to spruce up depressed Colón (pronounced ko-LOAN). Watch your back when exploring, as Colón has an unenviable reputation for crime.

LODGING

MELIÁ PANAMÁ CANAL

507-470-1100

Fax 507-470-1916

www.meliapanamacanal.com

Antigua Escuela de Las Americas, Lago

Gatún, 4 miles (6 km) west of Colón

Expensive

The former headquarters of the U.S. Army’s notorious School of the Americas has metamorphosed as a luxury hotel. It enjoys a privileged setting on a headland surrounded on three sides by Lago Gatún. The 286 guest rooms are stylish yet conservative and have all mod-cons, except Internet modems or Wi-Fi. Maybe General Noriega or another of the other thuggist right-wing dictators trained by Uncle Sam slept in your very bed! The coup de grace is a multi-level swimming pool. Activities include a zipline, kayaks, and plenty of excursion options.

NEW WASHINGTON HOTEL FIESTA CASINO

507-441-7133

Fax: 507-441-7397

nwh@sinfo.net

Avenida del Frente and Calle Bolívar, Colón

Inexpensive to Moderate

A historic grand dame rejuvenated with gleaming marble in the lobby, with chandeliers. The Fiesta Casino adds a contemporary note but draws a noisy crowd. The 124 guest rooms are comfy and have plenty of amenities, but still feel dowdy.

FOUR POINTS BY SHERATON COLÓN

507-447 1000

www.fourpoints.com/colon

Millennium Plaza, Avenida Ahmad Waked

Moderate

Colonial wooden home in Colón, Panamá

Swimming pool of Meliá Panama Canal hotel, Panamá

The port of Colón, Panamá

A stylish hotel (themed outside like the prow of a ship, complete with anchor) that is our first choice in town. In fact, this cruise-port hotel will please even the most discerning hipsters with its sophisticated contemporary decor and engaging bar. It has only a café-restaurant, and it charges for Wi-Fi, but the guest rooms have high-speed modems.

RADISSON HOTEL COLÓN

507-446-2000

Fax: 507-446-2001

www.radisson.com/colonpan

Paseo Gorgas and Calle 13

Moderate

In the Colón 200 cruise port terminal, this hotel competes with the Four Points for cruise-passenger business. It’s an ugly duckling from afar, but the rooms are graciously appointed in a conservative Edwardian fashion. Pay-per-view TV, high-speed Internet, and luxurious linens are bonuses.

ATTRACTIONS, PARKS, AND RECREATION

The town’s main street is tree-shaded Avenida Paseo del Centenario, a twin-drag boulevard that locals term “El Paseo.” It makes for a pleasant stroll, taking note of numerous monuments and statues, including those of John Stevens (Calle 16), the Chief Engineer of the Canal projects 1905–07; Ferdinand de Lesseps (between Calles 3 and 4); Christopher Columbus (between Calles 2 and 3); and Jesus Christ (Calle 1), shown with outstretched arms and known as El Cristo Redentor (Christ the Redeemer). Creaky clapboard houses in tropical ice cream pastels line the avenue.

A two-block detour west from the Christ the Redeemer statue brings you to the Hotel Washington, a venerable centenary grand dame remarkable for its Moorish façade and marble lobby that glistens anew after a recent facelift. It’s seen many illustrious guests, including Presidents Howard Taft and Warren Harding. Adjoining the hotel, on its west side, is the old Fort DeLesseps, built in 1911 as part of the Canal defense system. Its Battery Morgan has been restored and now displays artillery pieces.

If you have a morbid love for cemeteries, check out Cemeterio Monte de Esperanza (507-445-3418), better, and formerly, known as Mt. Hope cemetery; it’s on Carretera 32, about 0.6 mile (1 km) west of Colón.

GALETA POINT MARINE LABORATORY

507-212-8191

www.stri.org galeta@si.edu

Isla Galeta, 3 miles (5 km) northeast of Colón

Tuesday through Sunday 9–3, by reservation only

Admission: $5

This facility of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, on the eastern outskirts of town, offers a richly rewarding educational experience. Created in 1997 on the site of a former U.S. Navy satellite communications center, it includes a science and marine education center welcoming visitors. There’s an aquarium, and turtles, stingrays, etc., swim around in marine pools. And you can follow a boardwalk through the mangroves to see shorebirds, waders, etc.

Gatún Locks

Gatún, 8 miles (12 km) southwest of Colón. The longest of the three locks, this three-step lock measures 1.2 miles (1.9 km) long. It has a sheltered spectator stand with a running commentary of the operations broadcast in English and Spanish. Although much simpler, and not as high, as the four-level Visitors Center at Miraflores, this is treat enough.

You can drive across a narrow swing bridge on the north side of the locks to visit Gatún Dam, about 6 miles (10 km) upstream of the Río Chagres’ mouth (en route, you pass over the old French canal excavation). This great dam, completed in 1913, spans 1.4 miles (2.3 km) and is 2,100 feet (640 m) broad at its base—the largest earthen dam in the world in its day. Its main feature is a curvilinear concrete spillway topped by 14 gates that can be opened or closed to control the height of the lake. The HEP station that powers the Canal system is here.

The Colón-Achiote bus passes both the locks and dam. Taxis from Colón charge approximately $5 one-way, or $10 round-trip including a one-hour wait.

PARQUE NACIONAL SAN LORENZO

507-442-8346 or 433-1676

www.sanlorenzo.org.pa

Visitors Center El Tucán, Achiote, 9 miles (15 km) west of Gatún Locks

Daily 8–4

Admission: Free

San Lorenzo National Park protects 23,843 acres (9,653 ha) along the shores and inland of the mouth of the Río Chagres. The terrain includes shoreline mangrove forest, floodable cativo forests, plus lowland tropical evergreen forest fed by a whopping 130 inches (330 cm) of rainfall per year. It’s perhaps most famous as the setting for the U.S. Army School of the America’s Fort Sherman Jungle Operations Training Center (JOTC). Thousands of soldiers, and even astronauts, trained for jungle warfare and/or survival amid the snakes and creepy-crawlies. Today Fort Sherman, adjacent to the northwest entrance to the Panamá Canal, is a node for ecotourism. Meanwhile, the notorious School of the Americas, which trained a generation of Latin American dictators and other thugs, is now a hotel. You still need to show your passport to gain entry!

The Grupo de Ecoturismo Comunitrario Los Rapaces Achiote (507-6664-2339; http://achiotecoturismo.com), a local community group assisted by USAID, offers guided birding, hiking, and horseback riding. Wildlife viewing excels: bird species top 430, and the 81 species of mammals includes armadillos, coatis, spider monkeys, ocelots, and even jaguars and tapirs. The main trail is Sendero Achiote, which begins in the community of Achiote, about 9 miles (15 km) southwest of Gatún Locks and gateway to the remote Costa Abajo section of the Caribbean coast. An alternative is Sendero El Trogón. (A bus marked Costa Abajo departs Colón for Achiote hourly 10 AM–8 PM.)

The Smithsonian Institute of Tropical Research operates a canopy crane for scientific research in the forest canopy. As yet, visitors don’t have access.

Castillo de San Lorenzo el Real de Chagres: This fortress—a UNESCO World Heritage Site—stands atop a high coastal bluff and was first completed in 1597 to guard the mouth of the Chagres river. It was rebuilt in 1680 after a raid by Henry Morgan’s pirates. It’s a bit of a harpy to get to along a rutted dirt road, but the journey is well rewarded by sturdy albeit timeworn walls and cannon embrasures with rusting cannon in situ.

Castillo de San Lorenzo, near Colón, Panamá

SHOPPING

Many visitors who’ve heard or read about Colón’s duty-free Zona Libre (507-445-2229; www.zonalibredecolon.com.pa; Avenida Roosevelt and Calle) come here to shop. However, the world’s second largest free-trade zone after Hong Kong is intended for wholesalers only and primarily sells commercial items. Visitors can request a permit, obtainable at the main gate. Ostensibly, tourists can buy here but cannot leave the zone with a purchase, which must be delivered in-bond to the airport or cruise port.

The Colón 2000 cruise port (Paseo Gorgas’s www.colon2000.com) has duty-free and souvenir stores. For authentic pieces, I recommend a visit to MUCEC (507-447-0828; http://mucec.org; Calle 2 and Avenida Amador Guerrida, Colón), a non-profit cooperative workshop for distressed women, who produce pottery, woven items, etc. for sale.

Good to Know About

The Ministry of Tourism tourist information office (507-433-7993 ext. 92 or 447-3197; Calle St. Domingo Díaz #13) is in Puerto de Colón 2000 cruise port. Open Monday through Friday 8–5.

For the local police call 507-475-7011.

Portobelo and Costa Arriba de Colón

East of Colón the wild Caribbean shore known as the Costa Arriba de Colón (High Coast) is remarkably undeveloped, despite being blessed with beaches and historic gems. During the 16th and 17th centuries, this coast was a crown jewel of the Spanish Main and the port of Portobelo was one of the most prized and well-protected cities in the Americas. Every year the treasures of the region were marshaled here for the arrival of the annual flota (the Spanish treasure fleet), drawing pirates such as Sir Francis Drake. Great fortresses were built to stop their predations. Roaming the ruins today you can still hear the clash of cutlasses and the BOOM! of cannon. The region moves to the slow pace of a proud Afro-Antillean culture. Much, if not most, of the populace is black. The regional music, the dialects, the spicy cuisine all hint at a profoundly Caribbean potpourri. Offshore coral reefs and, inevitably, the wrecks of galleons and pirate vessels offer some of the best diving in Panamá. And the annual Black Christ Festival is an unforgettable time to visit.

Site of Fuerte de San Fernando, Portobelo, Panamá

Cannon at Fuerte de San Jeronimo, Portobelo, Panamá

LODGING

Several families in Portobelo rent rooms. Don’t expect anything fancy. These are simple budget accommodations. Places to consider include Cuartos Josefina (507-6519-5004); Hospedaje Antonio Esquina (507-6713-4516); Hospedaje La Aduana (507-448-2925); and Hospedaje Thamythay (507-441-7382).

BANANAS VILLAGE RESORT

507-263-9510

www.bananasresort.com

Isla Grande, 13 miles (20 km) east of Portobelo

Moderate

The most “resorty” of hotels along this coast, this venerable and poorly maintained beachfront property is popular with city-folk come to laze by the palm-shaded pool. Its 38 rooms come with CD/DVD players and are modestly comfy. Water sports include beach volleyball and kayaks. A little money and TLC would go a long way to recouping this hotel’s faded glory.

COCO PLUM

507-448-2102

www.cocoplum-panama.com

Buena Ventura, Portobelo

Inexpensive

Modest it may be, but this cozy, unpretentious 12-room hotel a five-minute drive west of Portobelo has all the ingredients for an enjoyable Caribbean vacation. The cabins, right on the beach, are splashed with tropical pastels; six are air-conditioned; four have fans. It offers water sports. The open-air Restaurante Las Anclas specializes in seafood and Colombian dishes.

CORAL LODGE

507-232-0300

www.corallodge.com

Santa Isabel

This landlocked eco-lodge is the only upscale option along the entire Costa Arriba. It’s made more appealing by its remote location, accessible solely by boat, and by its oh-so-romantic thatched bungalows built directly over the water along a boardwalk pier. It lies at the easternmost extreme of the Costa Arriba, on the doorstep of the San Blas islands (arriving guests are typically transferred by boat after flying into Porvenir). The furnishings can’t be termed deluxe, but the air-conditioned octagonal cabins are delightful enough and have high-pitched conical ceilings plus decks. The seafood restaurant is delightful and has a deck. You can even jump in to snorkel right off your deck! It has kayaks, diving, and an infinity-edge pool, and offers a range of activities, including jungle walks.

JIMMY’S CARIBBEAN DIVE RESORT

507-682-9322

www.caribbeanjimmysdiveresort.com

Nombre de Dios

Moderate

Although catering primarily to divers, this no-frills resort 3 miles (5 km) east of Nombre de Dios takes in all comers. It appeals to laid-back types who shun pretense with its five palm-shaded, wood-paneled beachfront cabañas. Offers horseback, fishing, and rain forest excursions, plus dive packages.

SISTER MOON HOTEL

507-236-8489

www.hotelsistermoon.com

Isla Grande, 14 miles (20 km) east of Portobelo

Moderate

Sitting over a rocky and secluded cove with dramatic vistas, this rambling 14-room hotel has some striking features, such as sparsely furnished rooms with loft bed atop natural rock bases; some rooms offer bunks. Nothing fancy here, but it has a bar and small swimming pool. Appeals to luxury-shunning castaways enamored of rusticity.

DINING

Portobelo has a smattering of simple restaurants. For atmosphere, head to Restaurante Los Cañones (507-448-2980), overlooking a cove on the approach road into town. This thatched restaurant serves seafoods, such as a delicious house specialty: pulpo en leche de coco—octopus in tomato sauce on coconut rice.

ATTRACTIONS, PARKS, AND RECREATION

Beaches

Although lacking the spectacular white-sand beaches of the San Blas islands, farther east, or of the Archipiélago de las Perlas, this coast does have some lovely beaches, although resorts and hotels are few. The best, and most developed is Isla Grande, 3 miles (5 km) east of Portobelo. It’s especially popular with folks who pour in from Panamá City on weekends and holidays. The snorkeling is good.

Water taxis for Isla Grande depart from La Guayra, 13 miles (21 km) east of Portobelo.

Nombre de Dios

15 miles (25 km) east of Portobelo. It’s a fabulously scenic drive to reach Nombre de Dios from Portobelo along a potholed rollercoaster road, which peters down to dirt in the town, which straddles an eponymous river. The town’s pedigree is ancient: founded in 1510 by conquistador Diego de Nicuesa, the port gained rapid import as the assembly point for bullion brought from Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá via the cobbled camino de cruces treasure trail. The marshy harbor was ill-suited to the role of treasure port, being open to attack by pirates and tropical storms. The port was pillaged by Francis Drake in 1572, after which Portobelo superseded Nombre de Dios. The town became a sleepy backwater, as it remains to this day. Most residents make a living from fishing.

In 1998, a shipwreck discovered off Playa Damas was proclaimed (unconvincingly) to be Columbus’ Vizcaina, which in 1502 sunk hereabouts during his final voyage to the New World. Only cursory recovery efforts have been made to date.

Parque Nacional Portobelo

(507-448-2165) Forming its own great bulwark around the town, this park spans 139 square miles (35,929 ha) of ocean, some 44 miles (70 km) of coastline, and a large range of forested mountains that rise inland. The park abuts Parque Nacional Chagres, forming a biological corridor for wildlife. It encompasses ecosystems from coral reefs and precious mangroves to tropical montane rain forest. At its heart is the town itself, still guarded by fortresses as reminders of a time four centuries ago when this unlikely spot was one of the three prize jewels of the Spanish Main (the others were Cartagena, in Colombia, and Veracruz, in Mexico).

Rivers snake down from the mountains and spill into Portobelo Bay, which is lined on its northern and eastern shores by mangrove, marsh, and moist forest. Safari trips up the Río Cascajal and Río Claro provide opportunities for spotting anhingas, caiman, crocodiles, sloths, monkeys, crab-eating raccoons, and even river otters. Local operator Selvaventuras (507-442-1042 or 6688-6247; selvaventuras@hotmail.com) has guided nature trips, including mountain hikes.

Portobelo

Ruta 31, 28 miles (45 km) east of Colón. Today a sleepy place except for when it bursts into life for the annual Black Christ festival, Portobelo was once a thriving port city. Tucked onto the southern shores of a deep oblong bay framed by sensuously curved hills, its setting is gorgeous. Hence the name: “Beautiful Port.” The best views are around sunrise, when fog floats eerily over the vales and waters and you expect a ghost ship to appear through the mist in Pirates of the Caribbean fashion. It’s a popular destination for yachters.

Portobelo was actually named by Christopher Columbus, who limped into the bay with worm-eaten ships on November 2, 1502, on his fourth and final voyage to the New World. The town, named San Felipe de Puerto Bello, was founded in 1597 after the port town of Nombre de Dios, a few miles farther east, was raided by Francis Drake. Nombre de Dios fell into desuetude and Portobelo, with its better harbor, grew rapidly as the departure point for the flota and the most important settlement in the Spanish territory of Nueva Grenada. Its climate was disagreeably humid, however, and the permanent population stabilized at no more than 1,000 people. Nonetheless, the announcement of the approach of the treasure fleet triggered a mass influx of traders, accountants, and military personnel for an annual trade fair, swelling Portobelo’s population tenfold. So much gold and silver bullion plundered from Peru and the Islas de Perlas arrived via the camino real treasure trail that ingots were actually piled in great mountains on the streets. Portobelo was never walled, but was fortified with batteries of cannons.

In 1597 the town escaped assault by a fleet of 26 pirate ships led by Drake, who sickened and died of dysentery before the attack could take place. The Spanish bulwarked Portobelo with twin huge fortresses—Todo Fierro (Iron Castle) and Fortaleza Santiago de la Gloria—to each side of the harbor entrance. Completed in 1620, they were no match for Welsh pirate Henry Morgan, whose cutthroat army of 450 men overran the fortresses in 1668, resulting in a 14-day barbarous plunder. In 1738, the town fell again, to an English fleet led by Sir Edward Vernon. Before sailing off, he blew up the fortresses. The destruction caused Spain to alter its treasure fleet practice. Although the fortresses were replaced with smaller, second-generation bulwarks, Portobelo never recovered its importance.

The colonial-era military installations, Customs building, church, etc. today form the Conjunto Monumental de Portobelo. The following sights are all must-sees:

Fortresses: Entering the bay from Colón, you pass beneath the Batería de Santiago, on the site of the former Fortaleza San Diego (destroyed in 1738). It still has baluartes (watchtowers) and cannon in their embrasures, attained by a stepped trail. It was built into the rugged hills on the southern shores to catch passing ships in a crossfire from Fuerte de San Fernando across the harbor, on the site of the former Fortaleza San Felipe (a water taxi from the town pier costs about $2.50). Some 218 yards (200 m) east of Batería de Santiago is the meager ruin of the low-slung Castillo de Santiago de la Gloria, completed in 1600 but destroyed by Henry Morgan’s gang and now mostly overgrown. In town, the harborfront is dominated by the ruins of Fuerte de San Jerónimo, with its main battery face-on to the harbor entrance. It dates from 1664, although what you see today is the remake in 1758 following Sir Edward Vernon’s depredations. It has cannon still in place.

Baluarte (watchtower) at Fuerte de San Jeronimo, Portobelo, Panamá

Iglesia de San Felipe: This twee whitewashed church, one block northeast of the town plaza, dating from 1814, has a two-tiered campanile and a simple gilt mahogany altar. Superstitious Panamanians flock to venerate a statue of Jesus painted with black skin, carrying a cross, and dressed in a purple velvet robe; the robe is changed yearly and is given by someone who has earned the honor. According to legend, the statue arrived in the 17th century on a Spanish ship bound for Cartagena, Colombia. The ship tried to leave several times but each time it was beaten back by storms until eventually the crew came to believe that the statue—El Nazareño—was to blame and left it behind. Later, the statue was proclaimed responsible for saving Portobelo from a cholera scourge that swept the nation in 1821. A special 11 AM Mass every last Sunday of the month features Afro-based folkloric congo music and dance. The Black Christ is the inspiration for the Festival del Nazareno each October 21 (see Seasonal Events).

Museo del Cristo Negro de Portobelo: This tiny museum (507-448-2024; daily 8–4; admission $1) is in the Hospital e Iglesia San Juan de Dios, next to the Iglesia de San Felipe, which dates from 1801 and stands atop the original, dating from 1598. The museum now displays robes used to adorn the Black Christ statue, and those worn by pilgrim-partyers during the annual festival.

Real Aduana: The twin-story Royal Customs House (507-448-2024; Calle de la Aduana; daily 8–4; admission $1), or “counting house,” opening to the plaza in the center of town, was the most important building during Portobelo’s heyday. Here, royal accountants kept track of the treasures flowing in and out of town and ensured that the Spanish crown got its cut. It dates from 1630 and was restored in original fashion in 1998, after being badly beaten up by pirates and by an earthquake in 1882. Today it houses a tiny museum with an English-language video on the history of Portobelo, plus maps, 3-D maquetas (models) of the castles, and other miscellany on the town’s history and folkloric culture.

Taller Portobelo: This workshop and gallery (c/o 507-448-2124 in Panamá City; www.tallerportobelonorte.com) sells works by a local artists cooperative. The artists work in naive styles that reflect the local heritage in vivid color. The Spelman College Summer Art Colony (404-270-5455; www.spelman.edu/artcolony), in Atlanta, Georgia, sponsors three-week residency courses for artists.

Scuba Diving

Diving is superb along the Costa Arriba. The Arrecife Salmadina reef clasps two Spanish galleons and a Beech C-45 warbird in 75 feet (25 m) of water. Heck, you can even join the search for Sir Francis Drake’s lead-weighted coffin, somewhere off Isla Drake, where he was laid to rest on January 28, 1596. Panama Divers (507-314-0817; www.panamadivers.com) and Scuba Panamá (507-261-3841; www.scubapanama.com) offer trips.

Good to Know About

The IPAT tourist information office (507-448-2200; Calle Principal; daily 8:30–4:30), 55 yards (50 m) southwest of the plaza, stocks a map “Costa Arriba y Conjunto Monumental Portobelo.”

WEEKLY AND ANNUAL EVENTS

In March, head to Portobelo for the Festival de Diablos y Congos (507-6714-6550; www.diablosycongos.com), when townsfolk celebrate their long and proud Afro-colonial heritage with traditional carnival-style music and dance.

Portobelo’s vibrant art community displays its finest at the annual Arte Feria (www.diablosycongos.com/visitportobeloSite/arteferia.html), every June. The festival includes theater, dance, and poetry, as well as art exhibitions.

The major event is the bi-annual Festival del Nazareno (October 21), which draws as many as 40,000 to Portobelo. Many peregrinos (pilgrims) arrive barefoot and shaved. Others crawl in on their hands and knees. Most wear an ankle-length, claret-colored velvet toga adorned with gold braid, faux jewels, and sequins. After sunset, the black Christ is taken from its perch in the church and paraded atop a litter. The bearers adopt a military-style sway, side to side, as they take three steps forward and two back—a real pilgrim’s progress. The fun begins after midnight, when the statue is returned to the church—signal for a very irreligious bacchanal to begin!

The Real Jack Sparrow

Fictional character Captain Jack Sparrow, of Pirates of the Caribbean fame, is a lovable rascal. A conniving trickster. A deceitful betrayer, even of his friends. Yet almost harmlessly inept, and endearing. Sparrow gives a bad name to pirates. In truth, the vast majority were remorseless cutthroats—the terrorists of their days, eager to torture, murder, and rape without scruple or hesitation. The ruthless sea rovers terrorized the Caribbean and Spanish Main for two centuries. Nowhere was safe. Often they operated in packs of 20 or more ships, sufficient to capture and ransack even the most fortified city. Panamá’s history is inseparable from their nefarious deeds.

Almost from the arrival of the first conquistadores, Panamá became a major conduit for the vast wealth of the American continent. Stupendous amounts of treasure—Colombian emeralds, Inca silver and gold, pearls from the Archipiélago de las Perlas—were transported overland to the ports of Nombre de Dios and, later, Portobelo to await the arrival of the annual flota, or treasure fleet, that would bear the booty to Spain. Pirates, predatory sea-going raiders, arrived in the conquistadores wake. At first they acted alone, in single ships; and later as packs, much like wolves. Because Spain possessed most of the Caribbean and mainland America, she became the natural target for foreign pirates, and privateers. Throughout much of the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain warred against England, France, and Holland, which authorized individual captains to attack Spanish ships and cities in the New World as a legitimate form of guerrilla war on the cheap.

Sir Francis Drake (1542–96) was, perhaps, the most famous—and effective—privateer. English myth paints him as a heroic figure, which perhaps he was. But he was also ruthless, and guilty of the most horrendous deeds. Drake started out in 1567 as a slave trader with his cousin John Hawkins. An encounter with the Spanish in 1568 prompted a quest for revenge. Thus, in 1572 he took up piracy against the Spanish Main. In July he raided Nombre de Dios (he succeeded, but retired after being shot); the following year he struck the Camino de Cruces, captured a mule train, and returned home with holds bursting with treasure. Queen Elizabeth granted Drake a privateer’s license and sent him on an expedition. The fleet seemed ill-fated, and five of the original six ships were lost to the elements. Entering the Pacific Ocean via Cape Horn in the Golden Hinde, he waylaid a treasure ship, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. He returned to England westward via Cape Hope to a hero’s welcome (he was the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe; only Magellan’s expedition had previously made such a journey). He was knighted by the Queen, who took half the share. After the outbreak of war with Spain, Drake returned to the Americas and ravaged the cities of Santo Domingo and Cartagena. Throughout the Americas, el draque became a term of fear. Following his illustrious role in the defeat of the Spanish Armada he pillaged the Iberian ports. In August 1595 he returned to the Caribbean. While preparing to attack Portobelo, he sickened and died (most likely of dysentery) and on January 29, 1597, was buried at sea in a lead-filled coffin.

The mid-17th-century gave birth to an entirely new group of pirates: the “buccaneers.” This band of cutthroats had started out innocently enough as a group of international seafaring hobos who had gravitated towards Isla Tortuga, an island off the north coast of Hispaniola. Here they lived relatively peacefully, raising hogs and hunting wild boar to sell as dried meat (boucan) to passing ships. The Spanish authorities, however, drove them out. They coalesced again and formed the “Brethren of the Coast”—a band committed to piracy against the Spanish. Their success drew like-minded villains. Soon they were a force to be feared throughout the Caribbean. The English authorities granted them official sanction as privateers, and a base at Port Royal, Jamaica.

They rose to infamy under Henry Morgan (1635–88), a socially privileged Welshman who took to piracy and proved an utterly ruthless and brilliant leader. His predations upon the entire Spanish Main became the stuff of legends, crowned in 1671 when he sacked Panamá City and, in 1688, Portobelo. Although Morgan stood trial for attacking Panamá City (England and Spain had just signed a peace treaty), he was treated as a hero and given a knighthood and eventually named governor of Jamaica. His death signaled the end of an era, affirmed in 1697 when England, France, and Spain signed the Treaty of Ryswick, committing themselves to stamping out piracy.

Children performing an Afro-Caribbean dance, Portobelo, Panamá