During the early 1980s, my life was filled with remembering. Remembering became my job, my task, my obsession, my tormentor. Remembering was difficult, but I could do it. Then in 1986, a new challenge confronted me. I was invited to accompany Bernard Cardinal Law and a group of Catholics of Polish ancestry on a pilgrimage to Poland.

I was flattered and deeply grateful for the opportunity to further my efforts regarding Christian-Jewish relations. But I was also terrified. Remembering from a distance was one thing. Going back to the scene of the atrocities was another. For weeks I agonized over my decision. Finally, with the support of my husband, Blanca, and my children, I decided to go.

We arrived in Warsaw during a blinding rainstorm. The atmosphere was depressing, closed in. To me, Poland appeared to be a graveyard. And indeed, in some respects, it was. In the 1930s there had been almost 3.3 million Jewish men, women and children in Poland. That summer, 1986, there were fewer than 5,000. There were no rabbis in Poland, and most of the synagogues had been converted into museums or warehouses.

Since I had never lived in Warsaw, I did not experience much emotional trauma while I was there. But Kraków was a different matter. My body began trembling as soon as we entered the city.

This beautiful city of mine had once been home to a vibrant Jewish community of 60,000. In 1986 there were perhaps 200 Jewish people living in Kraków—all of them elderly. One Friday evening I visited Kraków’s only remaining synagogue. That night my sadness turned to mourning and inconsolable grief. Once again, I questioned the sanity of my returning to Poland. I wrote:

Why have I come to pierce this desolation

When fierce emotions like a dormant beast

Are tearing at my gut and feasting on my fear

Until I taste the bitterness of yesteryear.

Have I perhaps returned to find a reason

To help explain the ugliness and treason?

Did I not plan to challenge God’s integrity

And make some sense of this insanity?

But... There is no special meaning to conceal

No pockets full of secrets to reveal

No thunder, no lightning, no great truth defined

Just a monstrous evil to torment my mind.

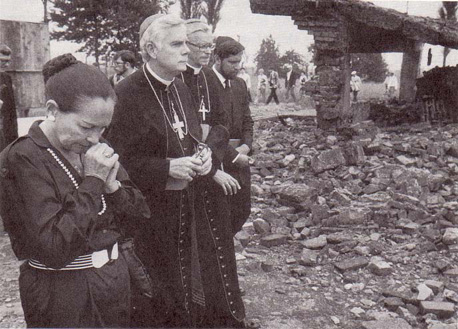

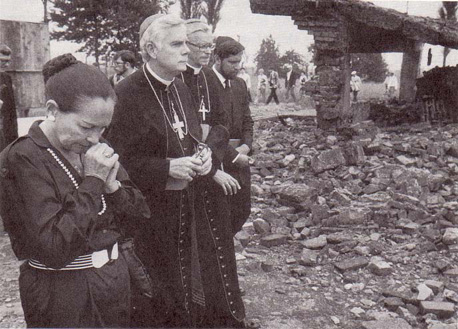

Standing in the Ashes of the crematoria at Birkenau. Sonia with Bernard Cardinal Law, Franciszek Cardinal Macharski and Leonard Zakim of the Anti Defamation League.

Photo by The Boston Globe, John Tlumacki

There were, of course, no answers to my questions, but still I continued on my journey back in time. In Kraków I stood by the ghetto wall on the Umschlag-Platz and remembered the night my mother had been taken from me. I prayed on the hill on which Plaszów had once stood and remembered the last time I had seen my father.

Our group journeyed to Auschwitz, and for the first time Jews and Christians prayed together there. I read some of my poetry and shared the following thoughts with my fellow pilgrims:

“For forty years, I tried to imagine coming back to this place of unspeakable horror. What would I feel? What would I think? How would I react standing upon the graveyard of our people? The questions are overwhelming. Do I evoke the names of my beloved parents—Janek and Adela? Do I recite the staggering numbers of my own loved ones, innocent men, women and children, condemned to death and slaughtered?”

I was haunted by the contradictions of this momentous experience. Standing upon the graveyard of my people was unreal and devastating, but weeping together amidst the ashes of the crematoria—the silent embrace between Jews and Christians—that was real.

The night of our visit to Auschwitz, I wrote:

This is unreal reality

A feeling empty and remote

I should devote eternity

To this colossal sense of loss

Instead I am confused, annoyed

I had prepared for other moods

For sadness, for insanity

But not this calm, horrific void

The hurt will surely come in time

With madness, anger, even tears

And I shall welcome these old friends

Whose touch I do no longer fear

Tonight my feelings are all wrong

I long to bring the sting of pain

Again to feel alive, aware

It is the numbness I can’t bear

And yet I hope the sun will rise

Once more to warm humanity

To bind the wounds and heal the scars

Of this unreal reality

After Auschwitz I had one final memory to confront. I knew I could not leave Kraków without returning to my neighborhood, my street, and the house in which I had once lived. Before I knew it, I was embarking on this last stage in my journey.

As we drove down the streets of Kazimierz, I vowed to keep my emotions under control. We headed toward the river Wisla and stopped first at Dietla #1, the house in which Norbert had once lived. I imagined him playing soccer with his brothers, and then rushing off to meet Blanca. My heart beat a little faster as I looked up and down the street. It really had not changed very much. Suddenly I found myself in front of Dietla #21—my childhood address.

Although the little variety store was no longer there and the buildings were a bit neglected, everything seemed familiar. My heart pounding, I climbed two flights of stairs and knocked on the door of my family’s apartment. When an elderly woman opened the door, I explained that I had once lived there and asked if I might come in.

Suddenly I was standing in my mother’s kitchen. I looked at the small table against the wall and saw myself sitting there, doing homework. As if in a trance, I peeked into the family room and saw my parents at Shabbat dinner—candles burning, wine poured. And I could clearly hear my sister giggling on the sofa.

Then I moved to the balcony. Looking down into the courtyard, I could see myself as a little girl playing hopscotch beneath two trees. Those trees were very special because, when Blanca and I were born, my father had planted one for each of us.

Suddenly I came out of my trance and connected with the present. The trees, were they still here? All at once, I desperately needed to know the answer. But I also feared the answer. Had the trees vanished as my people had?

Hesitantly, I looked down into the courtyard. There, in that dark and dingy place, I saw one tree—its roots exposed, breaking through the cracked and crooked courtyard floor. One tree! One tree had survived. To me, it became a symbol of life.

When I returned home, I told Blanca about the tree. As always, my sister was most generous. With her usual good humor she declared, “It’s your tree. I give it to you. I would never write a poem about it, but you will, won’t you?”

I did.

There stands a tree, a lonely tree

Planted for me in a hostile land

Planted with love by my father’s hand

The day I was born.

The roots gnarled and worn, broken and twisted

As if life ceased or never existed.

And yet, its limbs reach for the sun

And one (or two) with leaves

Green and tender, refused to surrender

And dared to survive. It is still alive.

I saw my tree, my birthday tree

Planted for me with my father’s hands

It stands defiant, haunted, lonely

The last, the only ... the tree of life.