Two

An Honor to the Country

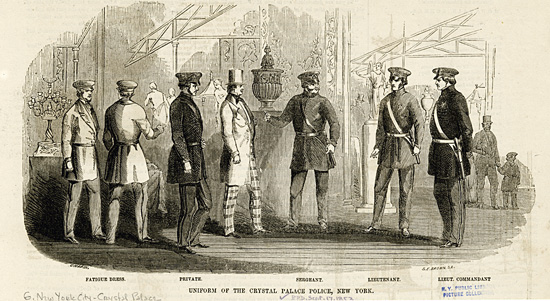

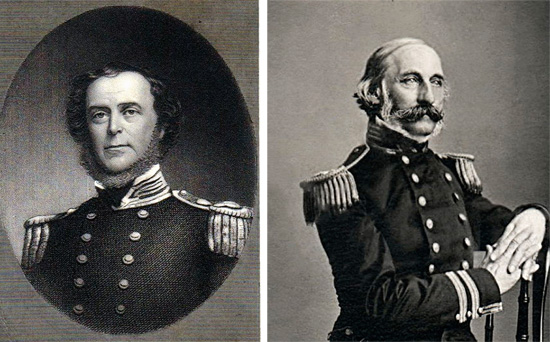

even before finalizing its choice of architects, Sedgwick and the Crystal Palace Association got down to business. They started advertising nationally and organized a network of state committees to solicit exhibitors, reaching such far-away places as New Orleans, St. Louis, and Minneapolis. They hired a general agent to find European exhibitors. They arranged to have the Crystal Palace made a bonded warehouse so foreign artists and manufacturers could bring their goods into New York duty-free; later they would also arrange with the city to set up a private force of 100 uniformed policemen for security and crowd control (Figure 2.1). To oversee construction, they tapped Christian E. Detmold for the job of chief architect and engineer. The German-born Detmold was a hard-charging iron manufacturer and surveyor for the War Department known for (among other things) designing a locomotive powered by a horse on a treadmill. Capt. Samuel Francis Du Pont, a socially connected and decorated naval officer, veteran of the recent war with Mexico, and something of an expert on exhibitions, got the job of superintending the final organization and allocation of space in the Crystal Palace itself. His assistant, who came with a burgeoning reputation as an astronomer and editor of American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, was another naval officer, Lieutenant Charles Davis (Figure 2.2).

[FIGURE 2.1] The Crystal Palace police arresting a pickpocket. “The police of the Palace make no inconsiderable feature in the show, with their neat uniform, marked caps, and erect, gentlemanly bearing. They are well drilled and ready; but with an American crowd, largely composed of women, they have little strictly professional duty. But they have done important service in one direction, by showing, on a small scale, the value of a uniform dress for functionaries whose official character is their strength” (Putnam’s Monthly 2 (Dec. 1853) 585). (Image courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.2 a and b] (left) Samuel Francis Du Pont, superintendent of the Crystal Palace and (right) Du Pont’s assistant, Charles Davis. In its July 13, 1853, number, the Times praised the pair for “the discipline and skill which have presided over every aspect of the arrangements.” It called both men “thoroughly accomplished scholars and gentlemen—prompt, courteous and energetic in every movement.” In the Civil War, as a member of the Blockade Strategy Board, Du Pont helped plan naval operations against the confederacy but left the service in 1863 after he was unfairly blamed for the disastrous ironclad attack on Charleston. Davis, too, would sit on the Blockade Board, the first time he had worked with his friend Du Pont since their Crystal Palace days. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Sheds for tools and offices seemed to sprout overnight on Reservoir Square, and within a month after the Association accepted the plan drawn up by Carstensen and Gildemeister, masons broke ground for the foundation. Contracts went out for 1,800 tons of iron columns and beams and 15,000 panes of glass, along with 750,000 board feet of wood and other material, which began to pile up on the square, contributing to the appearance of progress (Figure 2.3).

[FIGURE 2.3] Cast iron girders are hoisted into position atop the vertical columns using shear legs and pulleys. A pair of guys anchors the shears to masonry piers. This method of construction eliminates the need for scaffolding and was, until now, seen primarily in shipyards. (Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York)

At the end of October 1852, workmen raised the first column into place while the governor, the mayor, Sedgwick, and a gaggle of other dignitaries looked on approvingly and nattered about great things to come. Some 2,000 people observed the proceedings, many from atop the ramparts of the Croton Reservoir, a popular vantage point overlooking the construction site (Figure 2.4). Everyone cheered while cannons boomed and Dodsworth’s Band “played delightfully.”1

[FIGURE 2.4] Reservoir Square, looking west from atop the Croton Reservoir with the Hudson River in the background. This view was published in the March 19, 1853, issue of Barnum’s short-lived Illustrated News of New York. (Image courtesy of the New York Public Library)

Construction on Reservoir Square continued throughout the winter and following spring. It made an impressive spectacle, by all accounts, with hundreds of men at a time “crawling like flies over the huge dome, men hanging like spiders from the lantern, men on scaffolding putting in glass, men inside making the galleries and laying the floors”—all scrutinized by the crowds that came up every day to this “newly-discovered Sedgwickian center of the metropolis” (in the happy phrase of journalist George “Gaslight” Foster) just to see how the building was coming along (Figures 2.5–2.7).2

[FIGURE 2.5] Crystal Palace construction site looking east from Sixth Avenue. In this view, the framing of the building appears to be nearing completion and elements of the facade are visible. (Courtesy of Alamy)

[FIGURE 2.6] The crowd watching work begin on the dome. Note that construction has also started on the Latting Observatory, which dates this view in the late spring of 1853. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.7] The dome under construction, towering over the Reservoir “Workmen perched, like autumnal pigeons on leafy boughs, clustered within and without the vast edifice,” gushed Horace Greeley, “and the magic web of improvement each day proceeded” (Greeley, Art and Industry, 16). As it neared completion, the Times likewise reported that “Scores of men, seemingly no larger than mice, hung pendant from the lofty and magnificent dome, coating its inner surface with the destined decorations” (New-York Daily Times, Jul. 13, 1853). (Image courtesy of Alamy)

Real estate speculators were hard at work, too, triggering a minor boom in the neighborhood. Weedy lots, neglected for years, suddenly fetched astronomical prices, and excavations seemed to be under way everywhere. Rumors flew (for a time) that the great Franconi would build his Hippodrome somewhere in the vicinity. The Brooklyn Eagle marveled at the way “buildings are going up like magic in the vicinity of the Crystal Palace … and enormous rents were demanded for mere shells. A room in one of the wooden buildings, opposite the Palace … was rented at thirty-five hundred dollars per year.” An especially enterprising fellow advertised in the Tribune that he envisioned “a first-class Hotel … fronting the Crystal Palace, to be erected complete by the first day of June next, on the south-east corner of 40th St. and 6th-Avenue. The building will be … five stories high, and replete with every modern improvement.” He would be willing to rent it immediately, in advance of construction.

Opinions differed as to whether this free-for-all was a blessing or a curse. The Home Journal was happy to find, directly across Sixth Avenue from Reservoir Square, “a new and really splendid icecreamery [sic] and restaurant, in which 800 people can be accommodated, with arm-chairs, at marble tables, at one time.” Even before opening day, visitors could expect all kinds of exotic sights within a few blocks of the Crystal Palace:

living crocodiles, mammouth [sic] oxen, the model of San Francisco, the Swiss bell-ringers, and many others. There are plenty of men with targets and percussion guns, weighing machines and telescopes. Bowling saloons are numerous; so are swings, whirligigs and contrivances for wheeling people up half a hundred feet into the air. The cake and apple stands are past counting.

The Times, on the other hand, expressed misgivings about the increasingly seedy appearance of the area. “Wooden houses—many of them very frail-looking structures—are running up for the accommodation of visitors, and as temporary stores,” the paper observed. “For the latter as much as $200 per week has been demanded in advance.” In fact, everything thereabouts seemed to be made of crystal: “There are Crystal Stables, and Crystal Cake Shops, and Crystal Groggeries, and Crystal ice-cream Saloons. One old woman has set up a Crystal Fruit Stall, at which oranges and bananas, in every stage of decomposition, may be purchased. We noticed a dilapidated hovel on Sixth-Avenue, which was called by its proprietor the Crystal Hall of Pleasure.” (The area’s “vacant lots, rocks, and deep pits, with relics of country shanties” have nothing else to offer, the paper conceded on another occasion.) The Constitution of Middletown, Connecticut, warned innocent country folk to avoid “the hosts of liquor shops and places of low amusements in the neighborhood” of the Crystal Palace, which had spoiled whatever benefit the nation stood to gain from it. “They occupy the whole of the streets on two sides of the Palace, where they are arranged in long rows….” Why the city’s Common Council didn’t do something about this unsightly carnival was a mystery. But the influence of what Scientific American called “crystalization” wasn’t confined to the blocks around Reservoir Square. The Crystal Stables had recently opened downtown, it remarked, as had the Crystal Bakery. “And on the docks the other day we had an opportunity of drinking ‘Crystal Palace ice-cool lemonade—one cent a glass.’ ”3

Around the end of the year, thanks to the diligence of the Association’s agent abroad, the first foreign exhibits began to arrive—“flowing in daily,” said the Tribune—from all corners of Europe. The sultan of Constantinople pledged to send exhibits from his country, “some very fine plaster casts of antique and modern statues” were expected any day from Germany, and so on. The Association meanwhile continued to stoke curiosity about the event with a national appeal for exhibitors, vowing that the Crystal Palace would be “the largest and most beautiful edifice in the country”—a boast that in the months to come would be spread far and wide by New York editors and publishers. Their message even found its way deep into remotest Minnesota, in mail carried twice a month over frozen rivers by pony-sled, emboldening a St. Paul booster named William Le Duc to wrest $300 from the territorial legislature to mount an exhibit in New York.

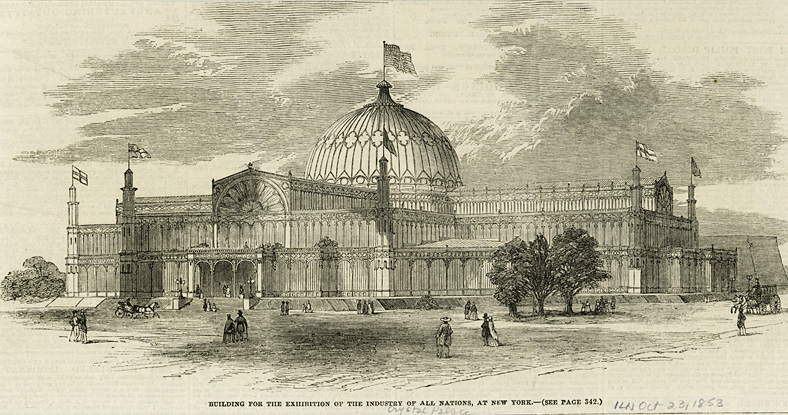

Scientific American, which had earlier raised a hue and cry against the Crystal Palace, now seemed to come around, too, even scooping the Association with a “superb representation” of the building (Figures 2.8 and 2.9). The magazine still thought James Bogardus had the more desirable plan and that no one anywhere knew more about building with iron. Nonetheless, it reasoned, “since we are to have a World’s Fair in New York next year, we now hope it will be an honor to our country…. In fact we know the Exhibition will be a benefit to New York city.” Such an event, the magazine said, is sure to attract a “whole army” of Americans as well as visitors from abroad, maybe even Queen Victoria herself!4

[FIGURE 2.8] On the first page of its October 23, 1852, issue, Scientific American published this view of the Crystal Palace from Sixth Avenue, commissioned at “great expense,” and offered copies for sale at $10 apiece. It depicted the building with remarkable accuracy before construction had even begun. The Crystal Palace Association probably had its own official view of the building, because only weeks later, at the ceremony for the raising of the first column, the superintending engineer handed out a “beautifully executed lithographic representation of the building as it will appear when finished” (New-York Daily Times, Nov. 1, 1852). On November 23, the Daily Times reported that this lithograph had been widely reprinted in the American and foreign press. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.9] One of many versions of the Scientific American–conjectural view, embellished with crowds and traffic. When this version appeared, construction had only just begun. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

Things did not go according to plan. Work on the Crystal Palace steamed ahead under a cloud of acrimony and wounded feelings, so dark at times that completion of the building must have seemed unlikely. Certainly it wasn’t the smooth triumph of private enterprise and know-how that it is often said to have been—unlike its counterpart in London, which had a much easier career because, thanks to Prince Albert, it could always count on royal support.

To hear Carstensen and Gildemeister tell it, the trouble started almost the minute their plan was accepted, when the Board of the Association eliminated the building’s basement in a foolish attempt to save money. Not only did this lower the entire structure by about six feet, accentuating the bulk of the Reservoir in the background, but Detmold then realized he had nowhere to store heavy equipment or to display paintings. So they had to replace the eastern-most entrance with an “unsightly” two-story addition, right next to the reservoir wall and some 450 feet in length. This caused “serious injury to the symmetry of the principal edifice.” Scrapping the basement also reduced the total exhibition space by 150,000 square feet, almost 3½ acres, leaving only a little more than 5½ acres. (By comparison, Paxton’s Crystal palace boasted fully 16 acres of exhibition space.)5

The man in charge of the machinery department then discovered that an important beam engine would not fit in the new addition, so its roof had to be raised at the last minute, wasting more time and money as well as doing further damage to the overall appearance of the building. None of this would have happened, Carstensen and Gildemeister claimed, if the directors of the Association had stuck to the original plan—or at the very least not waited until the last minute to make up their minds about modifications. With the basement gone, moreover, they had to scrap the fountain under the dome. In its place they decided to put a huge equestrian statue of Washington by Carlo Marcochetti that the cognoscenti greeted with howls of derision exceeded only by their contempt for a nearby statue of Daniel Webster (Figures 2.10–2.12). Happily, nothing came of misguided suggestions to remove the second-story galleries and replace the dome with an open-air court.

[FIGURE 2.10] Underneath the great dome. (“The American Crystal Palace.” The Illustrated Magazine of Art 2, no. 10 (1853): 250-64. JSTOR.)

[FIGURE 2.11] Marcochetti’s much-maligned equestrian statue of Washington, made of plaster painted to look like bronze. “It is bad,” scoffed the Tribune. “It is beneath mediocrity … a colossal abortion … a bag of meal on horseback.” It didn’t help that Marcochetti used the same horse for a statue of Richard the Lionhearted previously shown at the Crystal Palace in London and now standing outside the houses of Parliament. Happily, the reorganization of 1854 saw the statue removed from its pace of honor under the dome and banished to the east nave. Four years later, following its destruction in the 1858 fire, the Times noted, “no one is sorry. An impossible horse, best ridden by an impassive clod, was not an agreeable object.” (Greeley, Art and Industry, 55–56; New-York Daily Times, Oct. 7, 1858. Also, Goodrich, Science and Mechanism, 255; and Silliman and Goodrich, Illustrated Record, 52, 62.) (Image: The World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54. Courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.)

[FIGURE 2.12] John Edward Carew’s Webster. “Absolutely, this statue is a disgrace to its maker, and an outrage on the memory of its subject…. We do not believe there is in town a wood-carver, who cuts figure-heads for ships, who would not lose all his customers if he supplied them with such work as this” (Greeley, Art and Industry, 56). “Probably the worst thing in the Exhibition,” agreed Goodrich (Science and Mechanism, 255). (Image courtesy of the New York Public Library)

Fearing that no one source could fill all its orders alone, the Board also let contracts for iron beams and castings to over two dozen shops in states as far away as Delaware when only one or two nearby would have been more easily managed (Paxton had only a single firm to work with). In addition, the foundries immediately jacked up their prices, forcing the Association to spend time renegotiating all the contracts. The roof leaked, too, because the Board ignored the initial design for gutters and louvers. It allowed Detmold to waste a couple of months experimenting with “some novel ideas” for the construction of the dome; at one point he even entertained the embarrassing idea of having the dome built in England! When it came time to decorate, the Board ignored the wishes of the architects and turned the job over to one Henry Greenough, brother of the late sculptor Horatio Greenough. Employing platoons of painters who spoke only Italian, Greenough made key decisions about color and other matters that risked “the destruction of all beauty in the building”—painting the inside of the dome yellow instead of blue with red and white stripes, for example, causing it to appear one-third smaller than it was.6

To make matters worse, the Board failed to establish clear lines of responsibility and authority, so that Carstensen and Gildemeister “frequently clashed” with engineer Detmold and had to do the work of others:

We superintended the surveying of the ground, the excavation for the foundation, and the foundation-work itself. We also inspected the execution of the work in the pattern shop and the iron-works…. At the same time we had to furnish working drawings for every detail of the construction…. We absolutely assumed the duties of the working officials in addition to our own, and superintended portions of the enterprise … we had not contemplated as devolving upon us.

Hardest to bear was a whispering campaign to the effect that the architects alone were to blame for what Harper’s called “numerous and vexatious delays.” Like Paxton, the two men should have “stood honored before the world … as the leaders and executors of a great enterprise,” only someone—they weren’t naming names but almost certainly meant Detmold—was conspiring to destroy them first:

There was a steadiness and persistency about [these rumors]; a skillful and willful misrepresentation of motives, and misstatement of facts, which rendered it evident at once that a secret and clandestine influence was being brought to bear against us. Numberless absurd rumors were set in motion, whispered from one to another, occasionally re-echoed by the press, and eventually, as is always the case, credited by many.

Their fee for so much trouble came to a modest $5,000—they suggested half in cash up front, half “as soon has the receipts of the Exhibition shall amount to 10 per cent of the cost of the building.” The Association paid them $4,000. Of course, Carstensen and Gildemeister conceded, something will always fail to go as planned—problems must be expected in a project of such size and complexity—yet “whatever mistakes may have occurred during the erection, and in the completion of the Crystal Palace, they are not attributable to us.”7

The Association had a different story, naturally. In their version, Carstensen and Gildemeister were uncooperative and touchy to the point of paranoia from the start. First, the two priced the Crystal Palace at $300,000—eventually it cost twice as much—knowing full well that the Association’s charter limited what it could raise for the building to $200,000. Then they held up construction by arguing at every turn with Detmold about perfectly reasonable money-saving alterations. They didn’t deliver the necessary working drawings and specifications when asked, embarrassing the Association and forcing it to push back the grand opening from March 15 to May 1, and then finally to mid-July 1853. Even at the last minute key elements still remained unfinished, however.8

At the end of November 1852—just a month after the first column had been raised on Reservoir Square—Sedgwick let it be known that the Association had probably made a mistake trying to do business with two relatively unknown characters in the first place (and a standard background check would have revealed that Carstensen had a history of quarreling with the Tivoli management until they decided to let him go). “When your plan was first submitted to us,” he said in one of many irate letters, “you were all but total strangers to the members of the Board”:

one of you [Carstensen] just arrived in the country. You had for competitors, architects and mechanics of great reputation and influence, but the Board selected your plan on its own merits, without other recommendation or support, simply because they thought it the best, and because they believe that the beauty and originality of the design furnished proof that you fully appreciated the scheme and purposes of the Association, and gave an earnest of your future devotion to its cause. It is with deep pain that the Board find themselves mistaken in this just expectation.

The Board’s dissatisfaction with their two architects became a matter of public record in the catalogue of the Exhibition, published in 1853, which lavished praise for the Crystal Palace on everyone except Carstensen and Gildemeister, whose names, tellingly, nowhere appeared in the text. Nor were the two recognized during the official opening-day ceremonies but sat anonymously in the audience. Horace Greeley was outraged by this “ignorant, stupid, vulgar” snub of the artists and mechanics who did all the work. “True to the barbarism of this country,” he fumed, they were “thrust aside for epaulettes and white cravats.” When the Crystal Palace in England was inaugurated, “the working-men who built and stocked the wonderful edifice, were kept like Roman slave-artists and laborers in the servile back-ground of swinish caste, yet there, even amid the shams of state, Mr. Paxton, the genius who waked it to life, was on the platform. But where we would ask, were the architects of our Palace, Mssrs. Carstensen and Gildermeister [sic]? Why were they not on the platform?” Where was Cyrus McCormick, the man whose reaping machine saved the country from disgrace in London?9

By 1855 Carstensen had gone back to Denmark, without either his wife or Gildemeister—ostensibly to work on a new amusement park because he had lost so much money on the Crystal Palace, yet doubtless happy as well to get away from all the unpleasantness in New York. Less than two years later, in January 1857, he died in Copenhagen, allegedly penniless and alone. Other than a few lines in Scientific American, the event passed unnoticed in the local papers. His wife, Mary Carstensen, did not remarry and remained in the city, perhaps with one or both of their two sons, until her death in 1880. Gildemeister stuck it out until 1857, when a financial panic and labor unrest ruined the architectural business, and he returned home to Bremen, Germany. His death there a dozen years later likewise went unremarked in New York. Engineer Detmold, the architects’ nemesis, sailed for Europe soon after the Crystal Palace opened. He made a lot of money in coal, began collecting art, and settled in Paris. At some point he returned to New York, where he died in 1887. In his obituary, the Times called Detmold the “chief promoter” of the Crystal Palace and implied that it would not have survived “as great vicissitudes as have ever fallen to the lot of any similar undertaking” without him. The paper made no mention of either Carstensen or Gildemeister.10

Everyone seemed to agree that the Crystal Palace would bring a flood of visitors to New York when it was ready, but when would it be ready? Scientific American, always glad to find fault with the Association, estimated that 100,000 people had come to town to witness the opening slated for May 1 (a wild exaggeration), but May became June and June became July, and still there was no word when the building would be done. When a violent hailstorm—the Times called it a “hurricane”—swept through the area on July 1, killing three workmen, smashing windows, and flooding the main exhibition floor, there was speculation that further delays would be needed for repairs. Crowds still came up to Reservoir Square to see how preparations were (or were not) moving along, although more and more of them also wanted to look at the unusual structure rising on the north side of 42nd Street, directly opposite the Crystal Palace. This was the Latting Observatory, the brainchild of a local inventor/hustler named Waring Latting.11

At some point toward the end of 1852 or the beginning of 1853, it had dawned on Latting that he could make money by charging people to climb hundreds of feet for a panoramic view of the city below, plus suburban towns and villages in New Jersey, Westchester, Queens, and Brooklyn. He issued $150,000 worth of stock, formed a board of directors, and, not having any experience in construction himself, hired an architect to draw up some plans. They started work in March and finished at the end of June, apparently with none of the finger pointing and backstabbing going on across the street.

The completed Observatory was an octagonal tower, 75 feet in diameter at its base tapering to a mere 6 feet at the top (Figures 2.13–2.15), a dizzying 315 feet above ground—350 feet counting the flagpole, the equivalent of roughly twenty-seven stories—the tallest building in New York City, higher even than the spire of Trinity Church, over twice the height of the Crystal Palace, and almost certainly one of the tallest man-made structures in the world at the time. In fact, only the Great Pyramid of Giza (over 450 feet tall) and a couple of cathedrals in Europe were higher.12

RIGHT [FIGURE 2.13] The Latting Observatory, with the 42nd Street entrance to the Crystal Palace is on the far right. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.14] The Latting Observatory was a purely private undertaking. But it appears so often in pictures of the Crystal Palace that it is frequently mistaken for a part of the New York Exhibition. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.15] The Pylon and Perisphere, two of the most recognizable symbols of modernity at the 1939 World’s Fair, appear here as reincarnations of the Latting Observatory and the Crystal Palace dome. (Koolhaus, Rem. Delirious New York)

Its frame consisted of eight timber spars bolted together and cross-braced, then secured to a stone foundation with iron straps. Patrons hiked to the top by means of a winding staircase, with several landings along the way to ensure “convenient opportunities for rest.” (The original plan called for a central shaft or “well” to be used by a steam-powered passenger elevator, which would have qualified as a revolutionary innovation had it ever been installed. It wasn’t.) On the uppermost landing, the directors of the observatory promised to mount an “immense” Drummond, or calcium, light “of sufficient power to light up the harbor of New-York,” plus “a monster telescope” said to show objects up to sixty miles away. Entering or exiting, moreover, everyone had to pass through a long, two-story annex containing shops and an ice cream parlor, as well as “dissolving views, cosmoramas, scientific and optical instruments, works of art, and many other objects, useful and attractive.”13

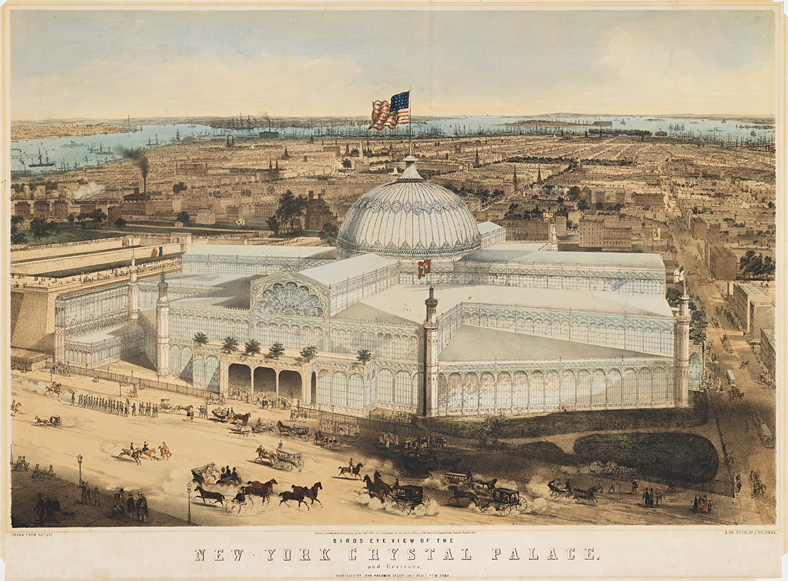

Lithographed bird’s-eye views of cities were ubiquitous by the mid-19th century, but (like that engraving of the Crystal Palace published by Scientific American) they were relatively expensive. They were also inherently imaginary—the artist’s conjecture about how the complicated landscape of a modern metropolis would look from high up in the air—typically enlarging significant buildings or geographical features to make sure the viewer grasped their location and importance. But a trek up Latting’s Observatory democratized the bird’s-eye view, so to speak. It was an invitation for anyone willing to pay the price of admission to see for themselves, fully and realistically, what had until now had been sheer speculation on the part of a few: the widening urban environment as it actually was (Figures 2.16–2.19). It could be an exhilarating experience, too, as a contributor to the Home Journal was surprised to discover:

[FIGURE 2.16] The Crystal Palace and Latting Observatory, a calotype by Victor Prevost. It was probably made in late 1853, after Prevost returned to New York from Paris in September of that year but before the dome was finished. (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society)

To tell the truth, we have been in the habit of regarding the building of this tower as a somewhat mad and Babel-like enterprise. But when, at the close of very hot day last week, we had panted up its innumerable winding stairs, and stood on the highest of its platforms, inhaling the most delicious of cool breezes, and looked round at the varied and gorgeous panorama that lay spread out like an immeasurable carpet at our feet, we then blessed the name of our Latting, and extolled his tower as a wise, timely and beneficent institution. The entire geography of this region lies there magnificently mapped. The rivers wind about, and stretch away in broad lines of silver. Their banks are done in emerald and gold. The cities—New York, Brooklyn, and the rest—are painted with faultless accuracy. The spectacle is interesting and splendid in the extreme, and richly repays the fatigue of going up such a multitude of steps.14

[FIGURE 2.17] “New York City from the Latting Observatory,” by Benjamin Franklin Smith Jr., 1855. Unlike most bird’s-eye views, this one shows the city from its relatively undeveloped northern outskirts looking south, rather than looking north from the Battery. The conspicuous curvilinear distortion of 42nd Street in the foreground suggests that Smith used a camera obscura of some kind, perhaps one equipped with a wide-angle lens. It does not, in any event, do justice to the striking appearance of the Crystal Palace. The official catalogue of the Exhibition said the exterior of that building was painted a “light-colored bronze,” while “all features purely ornamental are of gold.” (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.18] A careful comparison of this view with the previous one suggests that this bird’s-eye view was not from the Latting Observatory, despite striking similarities. The wide circulation of such images was unprecedented and helped build a national audience for the Crystal Palace Exhibition. “You may see the Palace lithographed, painted, engraved, and daguerreotyped in all the styles and sizes,” said Scientific American in its Aug. 27, 1853, issue. (Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York)

[FIGURE 2.19] The Crystal Palace from the northwest corner of Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street. The shacks on the corner are also visible in the view from Latting’s Observatory. It isn’t clear when this picture was taken, but inasmuch as the dome looks finished, it was probably in late 1853. (Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University)

“The ascent is a little fatiguing,” agreed the Times, “but it improves digestion.” The City Council was equally impressed and only narrowly defeated a measure giving Latting permission to build a 600-foot tower to be called the Washington Monument next to Castle Garden on the Battery (one alderman supported the idea because he thought the proposed monument was to rise directly atop Castle Garden).15

At last came the news that everyone had been waiting for and some probably thought they would never live to hear: the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, the first American world’s fair, would open on the 14th of July, 1853. The Crystal Palace wasn’t really ready, to be sure. The roof leaked, the dome still needed work, two-thirds of the exhibitors’ stalls reputedly had yet to be completed, and the floors remained an impassable jumble of “quaint foreign looking packing cases, carpenters’ tools, paint pots, half-opened bales, [and] vast derricks for uplifting heavy statues.” Hundreds of men are working around the clock to get things ready, said the Tribune, and “the whole is a scene of exaggerated confusion.”

On the bright side, New York teemed with excited visitors from all over the world. “It is the Exhibition summer,” crowed the Times. “Everybody that is anybody is in town, and now is the time for meeting people in the streets.” New York “is crowded and enlivened, as it has never been before…. The City swarms with strangers.” Harper’s observed approvingly that New York could boast of “more beards and barons; more Italian faces, and English plaids; more cosmopolitan talk and dress” since the Exhibition came to town, while a correspondent of The Southern Literary Messenger reported from New York that “the host of strangers with which the city is thronged” greatly exceeds the number of inhabitants “who are off on the fashionable summer tours, or sporting gay equipages at some renowned watering place, [which only] increases the prevailing enthusiasm, and gives a peculiar aspect to our over-crowded streets.” Exclaimed Putnam’s Monthly: the “grand convergence” of outsiders “makes our young city seem, for the time, a very London.” And the traffic! “Hundreds of stages and cars, by their ensigns and banners,” in the words of Scientific American, “proclaim that the Exhibition is the center of attraction.”16

The shabby grog shops along Sixth Avenue had meanwhile taken steps to spruce up and offer new attractions. The Times reported that one, calling itself “The New-York Volunteers’ Head-Quarters,” was now “ominously surmounted by a huge representation of a crocodile destroying a riderless horse.” Others were selling a novel concoction they called “root beer.” Nearby, too, one of those machines had appeared on which, “for a very small consideration, you can suffer the same effects as arise from a sea voyage, by being propelled through the air in a circle of huge circumference.” The canny proprietor had just “increased the number of cars for the convenience of the aerial voyagers.”17

On the appointed day, people began to show up outside the Crystal Palace soon after sunrise, congregating in Sixth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets, directly across from Reservoir Square. The crowd grew steadily larger, hour after hour, fed by the arrival of overloaded omnibuses, stagecoaches, and street railway cars (Figures 2.20–2.22). Hackney cabs and private carriages, threading their way carefully through the milling throng, brought nabobs in top hats seated alongside ladies in colorful silk dresses. Bemused newspaper correspondents remarked on the large number of slack-jawed tourists and oddly costumed foreigners, including groups of “very energetic Germans” and some “French gentlemen, invested in magical waistcoats.” Eventually, according to information published in the Times, upwards of 50,000 people must have filled the avenue and nearby streets. Everyone was in high spirits, despite the congestion and muggy weather. Vendors of ice cream, apples, soda water, and other “curative agents” did a land-office business. Every groggery and eatery in the neighborhood was packed. The French girl sporting a beard and mustache, the mammoth ox, the five-legged calf, the two-headed pig, the lung-testing machine, and other curiosities on display in the sleazy midway around the Crystal Palace, as “numerous as the jubilee-days of the Champs Elysées,” attracted mobs of “simple folk,” Horace Greeley wrote in the Tribune. When the doors finally swung open at ten o’clock, lucky ticketholders, upwards of 20,000 strong, surged through the turnstiles (a feature borrowed from the London Crystal Palace) to wander the cavernous polychrome arcades, gawking at an extravaganza of machinery, sculpture, furniture, porcelain, firearms, antiquities, and agricultural products.18

[FIGURE 2.20] Straphangers on opening day, July 14, 1853. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.21] The crowd begins to gather on Sixth Avenue. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

[FIGURE 2.22] Outside the ticket window of the Crystal Palace, July 14, 1853. (Art & Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

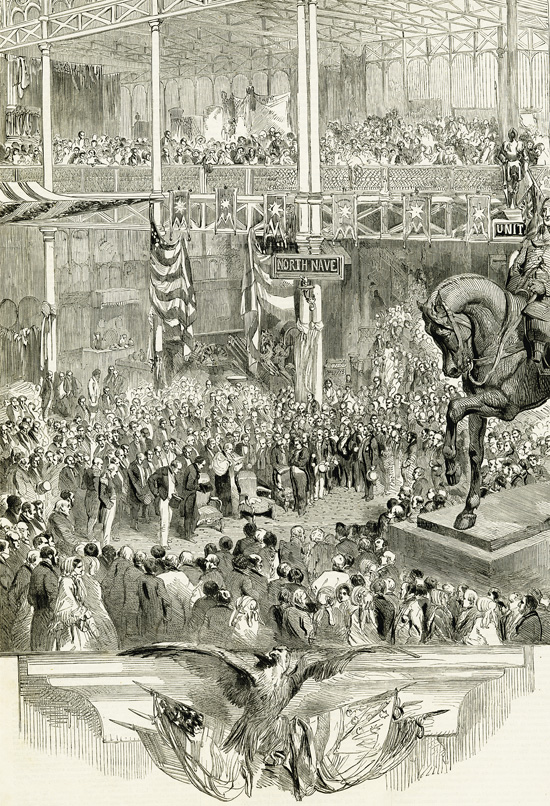

Around two o’clock that afternoon, the sound of marching bands outside signaled the arrival of Frank Pierce, the New Hampshire Democrat recently sworn in for his first and only term as president. Pierce had come up from the capital to preside over the opening-day ceremonies, landing at Castle Garden on the Battery that very morning and riding up Broadway on horseback, hatless, “erect as an Indian warrior.” Throngs of cheering spectators slowed his progress, while a brief downpour left him soaked to the skin. By the time he reached Reservoir Square, the usually convivial Pierce, already suffering from a severe cold, was bedraggled and exhausted. He snagged a dry shirt from the owner of an ice cream shop near the Crystal Palace. Someone produced sandwiches and a flask of brandy, enabling him to take his place on the platform. With him came a crush of dignitaries that included several cabinet members (among them Secretary of War Jefferson Davis), two U.S. senators, three governors, assorted army and navy brass, a large number of clergymen, foreign ambassadors, and judges, along with three military bands, an organist, and a chorus (Figure 2.23). Bishop Wainwright led the multitudes in a prayer that seemed to go on forever, after which the Sacred Harmony Society sang a chorale written for the occasion by William Cullen Bryant.

[FIGURE 2.23] Inauguration of the New York Crystal Palace—platform in the north nave—from a daguerreotype. (Art & Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

When it came his turn to speak, Pierce took only a few minutes. He thanked the organizers of the Exhibition for their work, predicting that it would confirm science as the source of all “our domestic comforts and our universal prosperity” while it advanced the cause of world peace. Then, voice failing, he sat down. “The President is not one of your grave and earnest orators,” one member of the audience conceded. Owing to the building’s poor acoustics, only guests in the first few rows heard him anyway.

An organist played a march, a band followed with a waltz, “full of youth and love,” and the Sacred Harmony Society closed the proceedings with an excerpt from Haydn’s Creation. Pierce retreated to the Astor House, still the city’s premier hotel, driven in a coach and six accompanied by Secretary Davis. The sun came out. That evening, at the new Metropolitan Hotel, the Association hosted a lavish banquet for the president and 600 guests. All in all, according to Greeley, the big event went off without a hitch—except that, once again, the architects received no more recognition “than if they had been two hod-carriers.” Nevertheless, wrote the newspaperman, from start to finish, July 14, 1853, was a once-in-a-lifetime experience to be remembered forever as one of the great days in American history.

The Times, too, rhapsodized that the inauguration of the Crystal Palace in New York was certain to be “hallowed in American History as connected with an event of rare importance to the nation…. [The] sun of American industrial splendor which rose to-day, shall never set, but shine like the arctic luminary, ever above the horizon.” Not everyone saw the future so clearly, to be sure. A correspondent of the London Weekly News thought the entire event vastly overrated. Everybody is talking about the New York Crystal Palace, he wrote—it is “the topic of the day”—and Americans brag so much about it one might think they, not Joseph Paxton, had invented the idea of building with iron and glass. But the sad truth is that as an exhibition of Industry and Art “it is a blank failure.” The building is half empty and will display some rather “curious things,” such as the 124-year-old slave who once belonged to George Washington. “What do you think of the showing up of a slave as an article of American manufacture? … He is to be taken to the world’s Fair for exhibition if arrangements can be made.”19

In its coverage of the opening-day ceremonies, the Times commented in passing that “iron construction on a large scale was and is entirely new in this country. No edifice entirely of iron yet existed in the United States, and the want of experience on the part of both architects and engineers presented serious obstacles.” A couple of weeks later the paper published a rebuttal by James Bogardus, whose own plan for the New York Crystal Palace, it will be recalled, had been rejected by the Association. Actually, Bogardus explained to the Times, as far back as 1849 he had put up a factory “entirely of cast-iron” on the corner of Centre and Duane streets in downtown Manhattan. A description and drawings of that structure had been published in London “before the London Crystal Palace was in contemplation,” meaning that “it is not only the first building erected entirely of cast-iron, but the first in any part of the world.”20

The Times was certainly incorrect that the New York Crystal Palace had been made entirely of iron. A principal reason it would go up in flames so quickly, after all, was the extensive use of wood for its floors, sashes, and dome. Nor was it the first building in the United States, or anywhere else, with a load-bearing iron skeleton. For decades already, British builders had been using cast-iron in mills, theaters, bridges, markets, cathedrals, train sheds, and houses—and selling prefabricated cast-iron modules to customers around the world. Even in the United States, the use of domestically manufactured iron columns, iron beams, and iron storefronts dates from the early 1800s. By 1853, cast-iron architecture was all the rage, and dozens of firms in New York and Brooklyn were reportedly experimenting with the commercial applications of iron construction. As The Illustrated Record of the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations put it, “The use of cast-iron had … already become common here for warehouses, to a degree exceeding even its use elsewhere.”21

Additionally, if the Crystal Palace wasn’t the breakthrough the Times claimed it was, Bogardus himself may have misrepresented somewhat the construction of his factory on Centre and Duane, which some sources say was framed wholly or in part with timber. So the Crystal Palace doesn’t necessarily qualify as the first all-iron building, either. Just about the only thing that seems beyond question is that nobody in America had previously attempted to build with iron on such a large scale—which is really what the Times had claimed in the first place.22

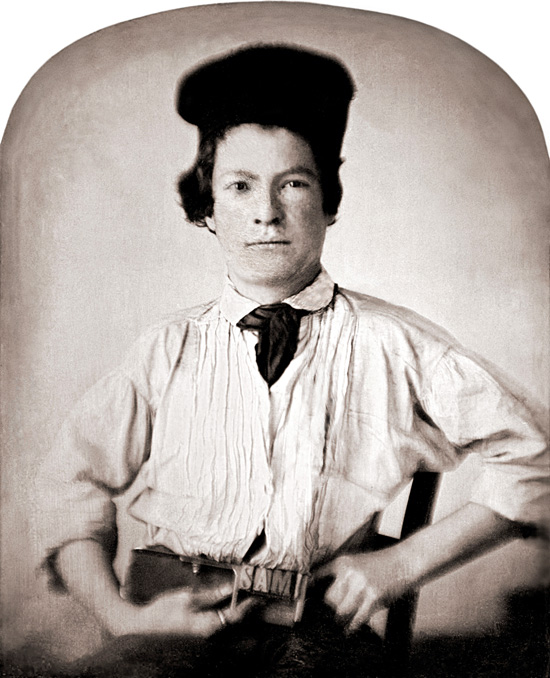

Judging by the fulsome praise it received around the country, in language strikingly like that used to describe Paxton’s Crystal Palace in London, the New York Crystal Palace was an instant success—“a dream of beauty and utility never to be forgotten by those fortunate enough to see it,” recalled a Minnesota businessman fifty years after he went all the way to New York from St. Paul to show off a birch-bark canoe made by Indians, an assortment of grains, and a live buffalo (which Sedgwick wouldn’t allow in the building). Seventeen-year-old Sam Clemens, recently arrived from Hannibal, Missouri, told the folks back home that it looked like “a perfect fairy palace—beautiful beyond description” (Figure 2.24). The Crystal Palace “is an immense structure, of iron and glass,” swooned the Democratic Review. It is “surmounted by a magnificent dome, which glitters in the sun’s rays, and is seen from some distance in approaching it on the avenue from below.” The National Magazine described it as a “noble structure … the largest edifice ever put up in this country … an honor to the nation.”

[FIGURE 2.24] Sam Clemens, in 1850, age 15, not long before he visited the Crystal Palace.

“The structure is very large,” Harper’s confirmed, “and architecturally is beyond all doubt one of the most strikingly beautiful fabrics ever erected in this country“—adding: “Seen at night, when it is illuminated by only thirty less than the number of burners that light the streets of New York, it is a scene more gorgeous and graceful than the imagination of Eastern storytellers saw (Figure 2.25).” The Illustrated Magazine of Art came up with the rather overwrought verdict that the Crystal Palace represented “a happy union of the airiness of tropical regions with the delicate, intellectual taste of a temperate climate.” Among people who had seen both Crystal Palaces—among Americans anyway—the consensus was that the one in New York, though smaller, easily outshone the one in London. Enthralled, Horace Greeley wrote in the Tribune:

[FIGURE 2.25] It was often pointed out that the Crystal Palace eventually boasted almost as many gas lamps as the rest of the city combined. When the lights were turned on, the effect was magical. Said Putnam’s with eerie prescience: “if the roof of the Palace were all of glass, the space it occupies would, at night, look from a distance, like a conflagration” (Putnam’s Monthly 2 (Dec. 1853), 583). (Image: New York Crystal Palace: Illustrated Description of the Building. Courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.)

This edifice starts in its delicate beauty from the earth like the imagining of a happy vision. Viewed at a distance, its burnished dome resembles a half-disclosed balloon, as large as a cathedral, but light, brilliant, and seemingly ready to burst its band and stay aloft. In every sense, the Crystal Palace is admirable. To us on this side of the water it is original. Nothing like it in shape, material, or effect has been presented to us. If it were to contain nothing it would alone be an absorbing attraction…. The brilliant and generally judicious coloring—on the insides as well as externally—of the glass and iron composing our palace, is a great improvement on the Quaker-like plainness of its London exemplar, which seemed but a paler reflection of those leaden British skies.23

Whether the Exhibition inside the Crystal Palace would inspire comparable adulation was the great unknown. If the stock market were any kind of barometer, it appeared that the months of delays and infighting had sapped investor confidence in the future. Prior to the opening, said the Times, the 4,000 shares of outstanding Association stock, initially offered at $100 per share, fetched $146—nearly 50 percent over par. After the opening, less than a week later, the price dropped to $125. By September, it had tumbled all the way to $77 and would almost certainly fall further. “But fortunately, the market value of the Stock affords no just criterion of the real value of the Exhibition,” the paper hastened to point out:

Its worth to the American people, and the degree to which they should cherish and use it, is to be found, not in the price of its stock when made the football of speculation, nor in the per cent of profit which it may return to those who brought it into existence,—but in the instruction it may convey to our mechanics and artisans,—to our farmers and laborers in every walk of life, and the impetus it may thereby give to those pursuits of Industry which constitute always and everywhere the elements of a people’s growth.

Even so, all indications were that it might take weeks, even months, before anyone could fairly decide if the Exhibition as a whole had succeeded or not. Despite the official opening on July 14, the Tribune wrote, “The Exhibition is in a state which repels investigation and disarms criticism. It is a bird but half liberated from the shell.” Week after week slipped by, and workmen still needed to finish setting up all the displays and getting a roof over the Machine Arcade and Picture Gallery. The Custom House had a large number of foreign consignments yet to process—everyone complained about lethargic customs officials—though more boxes and crates came in every day, obstructing the 40th Street entrance and blocking entire aisles inside. The refreshment saloons for ladies and gentlemen weren’t open for business yet. Benches or chairs for weary visitors remained to be installed. Not until August 2 would the Times announce that “the Machine Arcade is beginning to assume form,” although the steam engines that powered printing presses, looms, and other equipment still awaited necessary belts and pulleys. At last, too, “The Gentlemen’s Refreshment Room is rapidly approaching completion, and the necessary conveniences for the accommodation of visitors are well advanced”—meaning the installation of newfangled water closets, a subject rarely mentioned in the press despite its importance to the comfort of the public. But not until the end of August, fully six weeks after President Pierce helped kick off the Exhibition, were they even prepared to turn the gaslights on. All things considered, the Tribune counseled, people should probably hold off visiting until further notice, especially “our Country friends.”24

People came anyway. In droves—over a million of them before the Exhibition closed in 1854, according to the Association’s own reckoning. Walt Whitman, a young poet from Brooklyn (Figure 2.26), came so often that the police grew suspicious and began to follow him around. Like everyone else, Whitman thought the Crystal Palace itself was “unsurpassed anywhere for beauty,” especially at night, with the gaslights on. But nothing gripped his attention like Christ and His Apostles, a larger-than-life statuary group by the renowned Danish sculptor, Bertel Thorvaldsen (Figure 2.27). Among the most popular destinations in the Exhibition, Thorvaldsen’s sculptures—“awful, grand and sublime,” wrote John Reynolds, former governor of Illinois—always seemed to attract throngs of reverential visitors. Whitman himself said he spent many hours contemplating the scene. (There is no agreement, however, as to what influence, if any, the Exhibition as a whole may have had on Leaves of Grass, the first edition of which appeared in 1855.)25

RIGHT [FIGURE 2.26] Walt Whitman in his mid-30s, about the same time he visited the Crystal Palace. (frontispiece to Leaves of Grass (Brooklyn, 1856))

[FIGURE 2.27] Christ and His Apostles, by Thorwaldsen, the group that mesmerized Whitman. “Christian art has reached, in this immortal work … its noblest expression,” wrote Silliman and Goodrich. “It is undoubtedly the great artistic feature of the Exhibition” (The World of Science, Art, and Industry, 51). (Image: The World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54. Courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.)

In his Historic Tales of Olden Time (1832), John Watson noted with sadness that recent advances in transportation like the steamboat and the Erie Canal had caused the “rage for traveling and public amusements” to begin trickling down from the fashionable classes to people who could ill afford either the time or expense. A creeping disdain for “good old house habits” threatened to undermine old-fashioned republican simplicity and frugality, for “where is the motive for patient industry and careful economy,” he wondered, when everybody runs off for the summer to Niagara Falls, Lake George, Saratoga, Newport, or the beaches of Rockaway? Watson’s darkest fears came to pass sooner than even he could imagine. A mere twenty years later, an English visitor could report that Americans had entirely succumbed to the “mania for travelling.” Tourism had become big business for hoteliers, restaurateurs, and the publishers of maps and guidebooks—especially in New York, which seemed to empty out during July and August, when the bon ton and social climbers fled town for a country “vacation.”26

Urban tourism, however—traveling to see New York City rather than passing through it en route to Niagara Falls or some such place “in the country”—was still in its infancy in the United States. Despite nearly two decades of prosperity and an epic demographic expansion that boosted the population of Manhattan past the half-million mark, not to mention a feverish construction boom that would soon enclose Reservoir Square itself within blocks of homes and businesses, New York before 1853 had nothing like the Crystal Palace to reel in sightseers—not the famously exhilarating crowds and traffic on Broadway, not Delmonico’s or any other of the eating establishments called restaurants, not A. T. Stewart’s Marble Palace (1846), a massive dry-goods emporium on Chambers Street often heralded as the first department store in the United States, not even the mammoth new luxury hotels like the Metropolitan (1852) and the St. Nicholas (1853), both built to accommodate the hordes expected to come to town for the Crystal Palace and among the first to boast of accommodations designed with entire families in mind—central heating, for example, or hot and cold running water in every room—plus that new lure for blushing brides, the garishly appointed honeymoon suite. Few if any would make a special trip just to see Barnum’s Museum, the Custom House, City Hall, or the Merchants’ Exchange, although locals held many of these places in high regard.

By and large, as always, most people came to New York on business, not for pleasure. Sadly, said Putnam’s in early 1853, “New-York city is not wholly ideally magnificent.” The work of lining her streets with “structures of stone and marble” worthy of a great metropolis is only just getting under way, “in spite of the mean and unsuitable docks and markets, the filthy streets, the farce of a half-fledged and inefficient police, and the miserably bad government, generally, of an unprincipled common-council, in the composition of which ignorance, selfishness, impudence, and greediness seem to have an equal share.” At least respectable people tended to think that way. Waiting for the Crystal Palace to open, John Dalberg, the future Lord Acton, summarized prevailing opinion succinctly: “There is little to be seen in New York; it is not a fine city.”27

Only after the Crystal Palace opened in 1853 would New York even start to look like a desirable place to visit in its own right. For thousands of Americans, as for the teenager from Hannibal, Missouri, or the businessman from St. Paul, the Crystal Palace was irresistible “destination architecture”—the modern miracle they had been reading about in the papers and now felt the urge to see for themselves. It would be difficult to exaggerate the breadth and depth of this feeling.

Popular journalists like “Gaslight” Foster recognized that strangers to the city were no longer just passing through. “Your chief motive, of course, in coming to New York at the present time,” Foster said to his readers, “was to see the Crystal Palace.” Not, he continued, “that you had any correct or decided idea as to what the Crystal Palace was or is—but that, as every body has been for some months past talking and writing about the Crystal Palace, and as you have been told that all the world is to be there, you naturally feel as though you ought to be there too; and so, here you are.” The Times confirmed that the Crystal Palace “is much talked of in other parts of the Union, and its opening will be the occasion of visits to New-York by many who would else have never trod the streets of the metropolis.” Only a few years later, the same paper would credit the building on Reservoir Square with forever transforming the life of the city. “Until within a few years,” it said, “New York was deserted in July and August, but ever since 1853, our great Crystal Palace year, our citizens have no sooner quitted us for their Summer excursions than a flood of country people rush in to supply their places…. The round of life in New-York is therefore eternal. When the City goes into the country, the country comes into the City.”28

Increasingly, too, the idea that right-thinking republicans shouldn’t save up for recreational travel carried less weight than it once did. To hear Putnam’s tell it, Americans everywhere had been setting something aside for the trip to New York:

Far back in the country, while yet the burning weather lasted, the thrill of this novelty was felt; in sober villages, in lonely farm-houses, in log-huts still haunted by deer and the prairie-wolf. Even then, preparations were making, excuses devised, and pence put by, for a visit to New-York as soon as the harvest should be housed and the heat abated. The Crystial [sic] Palace was the universal theme, the moment any one appeared who knew any thing about it.

The Times even hinted that travel wasn’t a luxury any longer, and that people would be better off going to see the Crystal Palace rather than wasting their money on furs and the like:

The Crystal Palace will draw hitherwards its thousands. Towns-people, too used to the shows and uses of this stirring world, know little of the eager anxiety of the rural districts to witness that novel assemblage of men and things. The money, which is to pay passages to New-York, and fill the tills of expectant inn-keepers, is stored away religiously in preparation for the day. The outlay is set down among the necessities of the year, not with the luxuries. There will be self-denial to procure it; fewer new coats, bonnets, furs, and Christmas gifts next Winter. All the roads, for a while at least, will lead to New-York. And all will be crowded.29

Around the same time, newspapers, magazines, and guidebooks began encouraging people to think of the modern metropolis as an invention no less worthy of admiration than the steam engine or telegraph and to celebrate its creative energy as the perfect expression of American values. Increasingly, they emphasized the delights and benefits of city life, underlining the profusion of commodities on display in New York’s great stores and hotels and, by way of contrast, the hazards and poverty of the primeval wilderness. They began, too, writing about the city as no less picturesque or sublime than any natural marvel. It makes perfect sense that Latting’s Observatory would be so closely identified with the Crystal Palace, because it helped promote the idea of the city as a vital and appealing component of the American landscape. “There can be no more lovely scene than is exhibited in looking down upon the city,” said Humphrey Phelps in 1853, almost certainly from atop the Observatory:

Broadway running through the centre of the city, lengthwise, a living panorama of modern and American enterprise; the Fifth avenue, lined for miles with princely mansions; the Bowery, and the various avenues cut at right angles by a hundred streets; the Battery; the Park; and the numerous public squares filled with trees and playing fountains; and the spacious harbors filled with ships, afford a picture the most beautiful and magnificent.30

Always to be kept in mind here is that a trip to see the Crystal Palace was, for the vast majority of Americans, a psychological as well as a financial hurdle. For the big city not only had more of everything than the village back home, it challenged visitors from the pre-metropolitan countryside with people and things that existed nowhere else—buildings of iron and glass, department stores, huge hotels, oyster cellars, and oddly costumed immigrants, to say nothing of the con artists, pickpockets, and other rascally characters from parts of town that decent folk should only read about in the papers. Danger lurked around every corner, not least of which was the dangers of exposure, of being recognized as one of those clueless out-of-towners, of becoming the butt of someone’s joke.

A Times reporter, for example, told a story meant to poke fun at people ignorant of how things were done in the big city. It seems that one day in the summer of 1853, a couple of weeks after the official opening of the Crystal Palace, it rained heavily in New York until noon. Fewer people than usual ventured out to see the Exhibition, and those who did came encumbered with parasols, boots, and other foul-weather gear. Fortunately, to prevent them from poking wet umbrellas at, or dripping on, the displays, storage racks appeared at each entrance for their convenience. These racks “are attended by girls, who take charge of the articles deposited, and who give to visitors, in return, red checks, with printed numbers upon them corresponding to other numbers on the rack where the articles are placed.” People in the know handed over their umbrellas willingly; others would have refused to comply, if not for the fact that “the girls in charge appeared somewhat strong-minded” and a few “imposing” police officers hovered nearby in case of trouble. And then there were those who just didn’t grasp what was happening or what was expected of them. Serenely oblivious to modern city norms, they “thought the stands had articles for sale, and as the girls called out, ‘Umbrellas, Sir,’ replied with the utmost naiveté, ‘Thank you, we’re supplied.’ ”31

Anecdotes like that, told with a knowing wink, were not unusual in press coverage of the Exhibition, even in a place that otherwise welcomed visitors from remote parts of the country or abroad. Already, worldly-wise New Yorkers could not resist a good laugh at the expense of their naïve country cousins. Thus, just a week after the umbrella story appeared, the Times ran another account (perhaps by the same reporter) of “many faint-looking and wearied persons, looking sorrowfully around for some place to rest themselves.” No sooner had these “unsuspecting sight-seers” settled into some cushiony lounge chairs than a policeman appeared and told them to move on. As sophisticated readers probably guessed right away, “the comfortable lounges were for exhibition, not for use.” No doubt similar yarns were passed around about, say, the country bumpkins unaccustomed to the separate “retiring rooms” for ladies and gentlemen and their newfangled water closets—or at each entrance the “patent revolving registering gateway,” i.e., turnstile, “an English contribution to the Fair,” George Foster wrote, “an ingenious contrivance [but] unnecessarily clumsy and massive.”32

Not until the end of September 1853 was the mineralogical display ready for the general public, marking the de facto finish of construction eleven months after it began. Regrettably, a few exhibitors were already preparing to leave by the end of November, when they had been told the Crystal Palace would close for the winter. Instead of opening on May 1 and running for seven months as originally planned, in other words, the Exhibition had been fully operational for a little over two months, from late September through November. Hoping to recover their losses, the directors decided to stay open through the winter and brought in stoves. Now they proposed to keep going indefinitely. “The structure on Reservoir-square is universally conceded to be an ornament to the City,” they said. “The trade and enterprise of New York, of its hotels, its retail dealers, the omnibus and railroad interests, have all been materially assisted by it.”33

Scientific American, among others, wasn’t having any. “This is not a satisfactory apology” for flagrant mismanagement, it fumed. The Crystal Palace had been drawing several thousand paying visitors daily since the early summer, or around $9,000 per week—less than expected, but no grounds for complaint. In truth, the Association wound up in the red only because the directors shoveled out cash and neglected the interests of everyone but themselves or their friends. Consider, the magazine said, the $10,000 they awarded to Riddle for the lease on Reservoir Square. Consider the princely commissions they paid to their agents at home and abroad, the thousands they spent to buy a copy of Thorvaldsen’s group, the additional $10,000 they spent to buy Kiss’s Amazon, another popular sculpture, or their purchase of an extravagant eleven-piece silver tea service as a parting gift for Capt. Du Pont, chief superintendent of the Exhibition. Consider, too, that the final cost of the Crystal Palace will probably exceed $600,000—three times the amount originally anticipated, equivalent to at least $13.9 million today. No surprise, then, that the Association went broke. Fortunately, the magazine concluded, an election of new officers would take place early the following spring, at which time Sedgwick and his boondoggling cronies could be replaced by more competent men—“men who will infuse a new spirit into the affairs of the Association for the benefit of exhibitors and shareholders.”34