Reflections:

The Way We Came

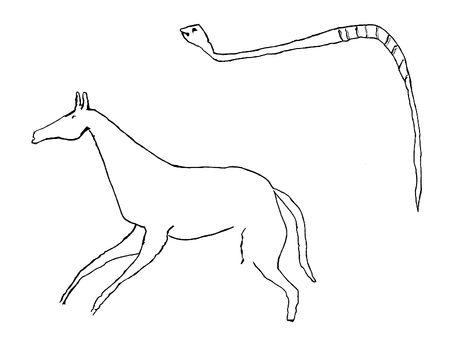

On my wall hangs a color copy of a photograph of a petroglyph.

after Sweem

If the story associated with the petroglyph is true, then the man who carved it was Crazy Horse. A Northern Cheyenne friend of his is believed to have been with him and witnessed the carving of it into a sandstone wall along Ash Creek a few miles southeast of the Little Bighorn River and the Little Bighorn battlefield. The photograph was taken by the late Glenn Sweem of Sheridan, Wyoming—a history buff and a fine, fine gentleman.

The carving is said to have been done a few days before the Battle of the Little Bighorn. I have no reason to doubt the authenticity of the petroglyph and that Crazy Horse was its creator, but then I may feel that way because I want it to be real. I have not seen it with my own eyes and never will if the last report I heard is true. The sandstone bluff, I was told, was washed away. Plaster replicas of the wall with the images on it have been made, however.

Some who have seen the actual petroglyph or the photograph or the plaster replicas believe it to be Crazy Horse’s signature. It is, of course, open to interpretation. I think it was more of a statement than a signature.

The snake, to some Lakota, symbolizes toka, or “enemy.” If the carver of this petroglyph was using the snake in this manner, then the horse—and whomever and whatever it represented—was being pursued or followed by an enemy or enemies.

At that point in his life, in 1876, Crazy Horse was certainly well aware that he had detractors, men who were envious of his status among the Lakota. When I see the photograph on my wall, I feel as though Crazy Horse was saying Lehan wahihunni yelo, or “This is where I am in my life.”

Or perhaps he was simply saying I was here.

Whatever the message, it does reach across from then to now, at least for me.

Crazy Horse came into the world at least four generations ahead of mine. He was born in the early 1840s, perhaps as late as 1845. I was born in 1945. As Lakota males, he and I have much in common. Enough of Lakota culture has survived through the changes during those four generations, fortunately, to allow my generation to identify strongly with his.

My childhood was similar to his in several ways. I grew up in a household where Lakota was the primary language, as did he. I heard stories told by my grandparents and other elders who were part of an extended family, as did he. My maternal grandparents, who functioned as my parents, were very indulgent, as Light Hair’s parents and the adults in his extended family were. I recall vividly the solicitous attention from my grandmother and from all the mothers and grandmothers who were part of the extended family circle, not to mention the women in the community of families in the Horse Creek and Swift Bear communities in the northern part of the reservation. Given these experiences, I know how it was for him as a boy growing up. The society and community and the sense of family—all of which were operative factors in his upbringing—were much the same for me. My 1950s lifestyle was certainly different than his 1850s lifestyle as a consequence of interaction with Euro-Americans, but traditional Lakota values and practices of rearing and teaching children have remained basically intact in the more traditional families and communities of today.

In my early days, as in Crazy Horse’s, every adult in the family’s extended circle and those in the community (village) were teachers, nurturers, and caregivers. The concept of “babysitting” was alive and well because everyone watched over all the children all of the time. In a sense there were no designated or hired “babysitters” because everyone was. Though the biological mother and the immediate family were the primary caregivers, the entire community or village had a role in raising the child. But in traditional Lakota families today these values and practices are still upheld and applied. Furthermore, among us there were and are no orphans. Though one or both biological parents may be lost to the child, someone in the immediate or extended family circle is ready to step in and function as a parent. A friend of mine on the Pine Ridge reservation had a particularly close relationship with his mother. I was surprised to learn later that the woman was, in our contemporary terminology, his stepmother because—as he explained it—his “first” mother had died.

The village itself, however, has changed. In the early days of the reservations in South Dakota, the old tiyospaye or family community groups attempted to remain together as much as the system of land ownership would allow. Actually owning the land, as opposed to controlling a given territory, was a new concept. As a consequence of the Fort Laramie treaties, the Lakota (and other tribes of the northern Plains) were “given” collective ownership of enormous tracts of land. Collective ownership—-everyone together owning all of the land—was not too far removed from the entire group or nation maintaining territorial control.

While the Lakota were still conceptually adapting to owning the land, the Dawes or Allotment Act of 1887 changed the rules; it changed collective ownership to individual ownership. Though the implementation of the act took several years because reservations had to be surveyed in sections, quarter-sections, and so on, and the population of adult males (eighteen years and older) counted, the culmination was the allotting of 160-acre tracts to family men and 80 acres to single men. Women were not eligible for initial allotment. Essentially the new system forced Lakota families to take up “homesteading,” and the encampments of old—several families living together—gave way to single families living on their tracts of land. Though the nearest friend or relative might be as close as just over the boundary line, the close physical proximity of living in a village was no more.

Even so, the ancient social more of functioning as a village still persisted. Mere distances could not destroy the sense of belonging to a group or a community. Friends and families came together at every opportunity and to meet every necessity. Dances, weddings, give-away feasts—and until the 1940s, going to the various government issue stations—were some of the reasons to gather together. Traveling by foot, horseback, or in horse-drawn buggies and wagons, the communities clung to as many of the old ways as possible.

Clinging to the old ways was not easy, however. In Light Hair’s boyhood the whites were unwelcome interlopers. At the other end of the hundred-year spectrum, in the 1940s and 1950s, we Lakota were still living under the firm control of the interlopers in the guise of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Government and parochial boarding schools took children from their families, and the process of learning became a group activity motivated by the prospect of punishment for failure rather than the one-on-one mentoring where lessons and achievement were more important than the rules.

Light Hair’s father was free to pursue his calling as a medicine man, but in my boyhood Christianity was telling us that our spiritual beliefs and practices were passé. As late as the 1940s, Indian agents (now called superintendents), frequently at the behest of white priests and pastors, sent Indian police to roust out Lakota medicine men. Their sacred medicine objects such as pipes, gourd rattles, and medicine bundles were confiscated and sometimes destroyed on the spot. It is likely that many of those objects later became museum displays as cultural artifacts. The medicine men were ordered to cease conducting and practicing their spiritual and healing ceremonies. But fortunately for us Lakota of today, our grandparents’ generation by and large employed the “smile and nod” tactic. When raided by Indian police, medicine men would smile and nod to avoid further persecution or even jail time. When the Indian police left they would haul out another pipe or make another one, and they would make sure their ceremonies went further underground.

There was no choice but to go along with the new ways to save what was left of the culture. It was necessary and acceptable to learn English so long as the Lakota language wasn’t forgotten, for example. Even today, many Lakota practice both Christianity and traditional religion, and there are enough bilingual Lakota - people to insure that the core of our culture is still intact. Smiling and nodding has its rewards.

For me there are positive links between Lakota boyhood in the 1950s to Lakota boyhood in the 1850s. For example, I learned to hunt and make bows and arrows from my maternal grandfather. His other male relatives or contemporaries were mentors for me as well. I learned the meaning of patience and gentleness (among other things) from my grandmother and - every other “grandma” I came into contact with. I was nurtured and taught and indulged much the same way Light Hair was. Childhood for me was wonderful and I’m certain Crazy Horse felt the same about his. Yet it is at times necessary to examine the differences between my boyhood and his.

The state of the Lakota nation as Light Hair entered his teen years was much different than it was during that same period in my life a hundred years later. In the late 1850s the Lakota nation was still strong and maintained a vast territory and the lifestyle of nomadic hunters living in buffalo-hide dwellings. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was the first treaty to establish static borders not of our choosing. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty redefined those borders and identified what is now the western half of South Dakota as the Great Sioux Reservations for “as long as the grasses grow.” In the 1950s, we were scattered across the state of South Dakota on eight reservations, the consequence of a series of “agreements” that whittled our traditional territory—then our “treaty lands.” The discovery of gold prompted the first “agreement” in 1875, and several others followed that resulted in the eight reservations.

By the time Light Hair was ten or eleven, Euro-Americans were a consistent presence and an increasing annoyance. The Oregon Trail cut across the southern part of the territory, and beginning in the late 1840s it became a steady stream of white emigrants moving east to west from late spring to midsummer. Tens of thousands of people, thousands of oxen, mules, and horses, and hundreds of wagons passed through every summer for twenty years. Those people carried with them many things new to the Lakota, some beneficial such as iron knives and cooking pots, and some destructive such as liquor and disease. Most of all, however, they brought change.

The concerns of the old Lakota leaders of the time are the realities that we contemporary Lakota live with today. Throughout the 1850s the growing Euro-American presence certainly impacted Light Hair and the Lakota who lived near the emigrant trail, derisively dubbed the “Holy Road.” Many of the older Lakota leaders of the time worried that the assurances of the white peace commissioners that all the emigrants wanted was safe passage through Lakota territory and space wide enough for wagon wheels were empty promises and a portent of the future.

They were right. In 1868, the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota returned to Fort Laramie for more negotiations. The Powder River, or Bozeman Trail, War had just ended. The federal government allowed the Lakota to think the soldiers were abandoning the forts along the Bozeman Trail—from south-central Wyoming north to the gold fields of Montana—because they had “lost” the conflict. In truth, they could afford to abandon the Bozeman Trail because they were developing an east-west rail line across Montana, a more direct route to the gold fields. Negotiating from the position of “loser,” the government’s peace commissioners successfully convinced the Lakota that, as “victors,” they had won what is now the western half of South Dakota. Furthermore, portions of the current states of North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska were designated as “ceded territory” where the Lakota could hunt. In reality, the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was the beginning of the end of the free-roaming, nomadic hunting life.

The late 1950s found us living in square houses in scattered communities across the reservations. Our lifestyle was largely indefinable and on the dole of the United States government. The buffalo-hide tipestola or pointed dwellings (more commonly referred to as tipi) were only memories. We were virtually powerless politically. But those circumstances were irrelevant to me as a child. My grandparents and I lived in a log house on a plateau above the Little White River, which my grandfather referred to as Maka Izita Wakpa, the Smoking Earth River. He never ever referred to the river by its new name. Perhaps it was his way of staying connected to the past.

That past came alive in the stories both he and my grandmother told. I can’t recall precisely at what point I realized that those stories were much more than just entertainment. There were, of course, the more whimsical stories of Iktomi, the Trickster, but even those always had a lesson to offer. Other stories were about people and events, many of which did not find their way into the history books of the interlopers nor coincide with their versions of the same people and events. The information in those stories were our history—family, community, and national history. The impact and the value of those stories, for me, are summed up in something my grandfather said one late summer afternoon when I was five or six. We had been walking along the Smoking Earth River a few miles from our house and came to the top of a hill. We stopped to rest and he grabbed me by the shoulders and turned me so that I could look back along the trail we had walked.

“Look back at the way we came,” he said. “Remember the trail we have walked. Someday I might send you down that trail by yourself. If you don’t remember it, you will be lost.”

That sentiment is why the medicine men smiled and nodded when the Indian police ransacked their homes and confiscated their pipes and medicine bundles. You can take away the things but you cannot take away the knowledge, the awareness. That sentiment is why, in spite of everything, the first generation of Lakota to live on the reservations clung to their ways. That sentiment is why, in spite of the intensive and extensive efforts of the government and parochial boarding schools, there is still a Lakota language, still a Lakota identity. We haven’t forgotten the trail we have walked. Hopefully enough of us have heeded Crazy Horse’s message and we will never forget that he was here.

My grandparents and their generation were not too different from Light Hair’s parents and grandparents. The elderly Lakota of the 1850s, in the face of the white incursion and the changes brought by them, were telling stories and reminding their children and grandchildren to remember the trails they had walked.

Handcrafting a bow out of ash is almost a lost art for the Lakota. My grandfather taught me because his father, White Tail Feather, and second father (stepfather), Henry Two Hawk, taught him to make bows and arrows. They learned it from their fathers and grandfathers. And the methods and process are the same as those that were taught to Light Hair—exactly the same. Each time I’ve had the opportunity to make a bow, a thought invariably passes through my mind: This is the way it has been done for hundreds of generations.

I make my bows the same way Crazy Horse did.

That is only one of many connections he and I have as Lakota boys.