409

This Is My Father

After his stroke in January of 2017, my father would occasionally sing to himself in Polish, very softly, with his eyes closed, as if he were tiptoeing across the fallen leaves of a long-distant autumn. At first, he told me that the songs were taught to him by Ewa Armbruster, the elderly piano teacher who’d hidden him in her home near the end of the Second World War. But once, when he was lying in bed and nearly asleep, just a week before his death, he said he’d learned them from his grandmother. Whatever the truth, he’d forgotten about them for many years. In fact, he was astonished that he could still sing in Polish.

Had his stroke opened a door to memories he’d once considered menacing?

One chilly afternoon in mid-April, I brought him a cup of fresh decaf coffee as a treat, and I found him standing by his window, watching the birds at our feeder, humming one of the old tunes. He took my hand and rubbed my palm against the grey stubble on his cheek and told me that he was so grateful for having recovered from his stroke, and the spring crocuses in the yard, and the good coffee, and for Ewa and all the songs he’d ever heard, that there was no room in him for anything but that gratitude. As he fought to smile, his big black eyes filled with tears, and I felt an upward rush inside me. Yes, I thought triumphantly, this is my father free of everything that has ever held him down or sealed his lips or set him trembling.

At that moment, I imagined that the two of us had entered in 410a holy space – an eruv. And yet I also thought – with a burst of panic – I’ll need this feeling of being united with him to sustain me when he’s gone, but will I be able to find it?

The Incandescent Threads

‘Dad, are you afraid to die?’ I asked him not so long ago – about three months before he passed away. It was a question that had been hiding inside my chest for more than seven years – since his cousin Shelly’s death in the fall of 2010. The eager sun peeking through the pink-blossoming branches of my cherry tree seemed to give me permission to finally speak it aloud.

He was standing on our picnic bench, spilling birdseed into the glass feeder, which we’d hung from a thick nylon cord between our apple trees and coated with olive oil, so that the squirrels couldn’t get to it and steal all the nourishment meant for his beloved blue jays and cardinals. I was gripping his slender, pale, bony ankles to make sure he didn’t lose his footing. He was having a good day – no discomfort in his back at all.

‘Nah, I’ve died many times before,’ he replied matter-of-factly. As I helped him down onto the lawn, he added, ‘But let me tell you, I’ve had times when there was a lot of pain, and that didn’t make it such a piece of cake. When I worked at the Library of Alexandria, I’m pretty sure I died of some sort of infection in my gut. God only knows what I ate – probably some badly cooked meat. The Egyptians weren’t all that hygienic. Hygienic – is that the right word?’

‘It’s perfect.’

‘Saying goodbye to my family and all those beautiful scrolls …’ He shook his head at the difficult parting. ‘I think that that’s why I always have to have a book with me in bed or I get really nervous.’ He jiggled the box of seed to produce a percussive rustle and did 411a wiggly little dance. ‘This time, crossing over to the Other Side won’t be so hard. After all, you and your family are safe, and I’m too old to keep fighting Mr Trump and all the other leaders who do such awful things.’ He shrugged. ‘You know, Eti, I tried pretty hard to do right by all the good people the Nazis murdered, but I see now that it wasn’t nearly enough.’

‘Well, at least, you helped stop the war in Vietnam. That was really important.’

‘I did what I could. Anyway, it’s time for you and your kids to take over. Your mom and Shelly are waiting for me, and Julie and Morrie and Uncle George, which pretty much makes me the last of the Mohicans.’

Could my father talk calmly about death because he really did believe in reincarnation? Or was it because the Nazis had forced him to face his mortality very early on? When I asked him, he patted my hand and said, ‘Both, I think.’

‘What about Shelly – was he scared to die? I never asked him.’

‘No, he’d made peace with the Angel of Death back in Poland – when he was sure he was a goner.’

‘When was he sure he was a goner?’

‘A Nazi caught him in the forest – where he was sleeping for the night. He didn’t tell you?’

‘No. What happened?’

‘Shelly played deaf and dumb. He made gagging noises and kept pointing to his ears and shaking his head.’ Dad imitated Shelly imitating a deaf man pleading for his life. It looked ludicrous but probably Shelly had been far more convincing; my dad was never as good an actor as his cousin.

‘So the Nazi believed that Shelly was deaf and let him go?’ I asked.

‘No. The bastard shot off his gun by Shelly’s ear. And Shelly 412jumped. The Nazi laughed, because he’d proved that Shelly was lying. But that wasn’t so clever. It gave Shelly time enough to pounce on him. He was strong as hell back then. The Nazi got off another shot, but it missed. Shelly punched him so hard that he broke his jaw – he heard the crack – and got the gun and shot him in the head.’

‘So he killed two people?’

‘Two people? What do you mean?’

‘Uncle George once told me that Shelly had killed a French cobbler,’ I said.

Dad puffed out his lips and shook his head. ‘George would know. But Shelly never told me.’

‘So maybe he killed even more than two men,’ I said.

‘I wouldn’t be surprised. No anti-Semites were going to stop Shelly – at least not without one hell of a fight!’ Dad motioned me to come closer and kissed my cheek. ‘I love it when you haven’t shaved for a few days,’ he said.

‘Why?’

‘It means you’ve become a man.’ He took a big steadying breath. ‘What a relief it is to know that you’ll never die in childhood.’ He tapped his fist against my chin to lighten the mood. ‘But who the hell knew you’d grow up so damn fast?’

‘Dad, what about Mom? Do you think you’ll see her again?’

‘I’m hoping that she and I will be reborn together,’ he replied. ‘Or is it she and me? My English today is abominable.’

‘I, I suppose, but it makes no difference.’

‘Anyway, when you find your other half, you keep on travelling with them through different reincarnations. At least, that’s what some kabbalists say.’ He showed me a mischievous grin. ‘Hey, you know what was a great day?’ he asked.

‘No.’413

‘When we stood out front of Trump Tower with that sign saying holocaust survivors against ignorant racist bullies.’

‘Yeah, I had a good time – at least until you got into that argument.’

‘Argument? Bah! That was nothing. I’ve had people spit on me. Some idiot kid in an Abercrombie & Flinch T-shirt screaming at me – that’s nothing!’

‘Abercrombie & Fitch,’ I corrected.

‘Whatever,’ Dad said dismissively. He trickled a bit of birdseed onto his hand and licked it up. ‘I like to try everything at least once,’ he said by way of an explanation.

When he handed me the box, I tasted a pinch of the mixture, but it was bitter and I spit it out.

‘I guess I’m the only birdbrain in the family!’ he observed, giggling merrily, and the fondness for me in his eyes made it clear that he wanted me to laugh too, but a knot of panic had formed in my chest. He stroked my shoulders with both hands and told me that everything was going to be okay.

‘It’s not!’ I said testily. ‘So don’t say it is.’

‘Better I go one day soon than seventy-five years ago in Auschwitz.’

‘Are those my only two choices?’ I questioned.

He giggled again. ‘Yeah, kiddo, given where and when I was born, and that I’m one hell of a nutty Jew, they are.’

Kiddo was what Shelly had always called me. Dad had only adopted the word after his cousin’s death. By then, Shelly’s wife Julie had already been gone for three years.

I left Dad alone to shoo away the squirrels from the birdfeeder and work on my latest painting. In it, me, Shelly, Dad and Uncle George were weeding a small garden filled with pink-and-white 414cosmos and golden coreopsis. Behind us was the Alexandria Lighthouse. And Chloris, the Greek goddess of flowers, was supervising our work with a demanding eye. Since George was one of the figures, I’d decided to put the garden inside a death camp. But I was having trouble making the barbed wire seem sufficiently evil.

That night, sometime after I’d added a guard tower to the top of the lighthouse, I discovered my father’s light on long after his usual bedtime, so I knocked on his door. He was reading a book on the meaning of the Sabbath in Judaism that I’d purchased for him. ‘Too exciting to stop!’ he told me.

On his tape player was a recording of my mother interviewing an old man from Izmir about the Sephardic lullabies he’d sung to his children. Dad always liked to hear my mother’s voice before going to sleep. Sometimes he’d change tapes throughout the night so she’d always be talking or singing while he slept. I noticed that he’d placed his favourite black-and-white photograph on his bedside table, beside his clock. In it, Mom is bringing him a big cup of just-brewed coffee. Dad is smiling at her with surprised delight and Mom is looking at him with charmed affection. I’m the toothless baby on his lap, giggling merrily, reaching out with his hand toward the photographer, who happens to be Shelly. When my father asked me to have this picture framed a few years back, he said, ‘Occasionally, Eti, while we’re travelling down our road, we stumble upon a perfect moment. Thanks to Shelly and his old Polaroid, I can revisit this one anytime I like.’

Now, I gestured toward the picture and said, ‘I love seeing you smile so genuinely.’

He nodded his agreement and said, ‘And this time we didn’t even have to do a second take!’

After we’d had a little laugh, I asked him if he’d forgotten his 415pills, since they were still clustered together in front of his clock, and he said that the yellow and orange tulips coming up in the garden – which he and my wife, Angie, had planted – had convinced him to stop taking all his medications except for an aspirin in the morning to keep his blood circulating. I argued against changing his routine, of course, but he looked at me hard and said, ‘I can’t let you or anyone else decide how I go. It’s too important. And I really don’t want to talk about it.’

I frowned because I didn’t want to admit he was right, and sat next to him, sulking.

‘Hey, I’ve got something important to tell you,’ he said in the tone he always used to cheer me up. ‘Just after your mom and I bought our house, back in 1969, I hid a metal box in the basement. You’ll find it inside a cardboard box stuffed with two old bedsheets. The cardboard box says Waldbaum’s on the outside.’

‘What’s in the metal box?’

‘A vellum manuscript. You’ll need to get it translated.’

‘What language is it in?’

‘Ladino mostly, with a little Hebrew sprinkled here and there. Get Isaac Silva to do the translation. He’s a professor emeritus of Jewish mysticism in Berkeley. I’ve spoken to him on the phone and he likes me. Don’t let his fancy British accent intimidate you – it’s just for show. He says he bought it while he was studying in Oxford.’

‘Bought the accent?’

‘Yeah, he’s from some coal-mining town, and his family was as poor as church mice. He told me his accent was holding him back, so he bought a new one. His number is in my address book.’ Dad held up his finger. ‘A few years ago, I started using Mom’s system, so look under Isaac not Rosa. Got it?’

‘Got it. Where’s the manuscript from?’ I asked.

‘Constantinople. It was written by Berekiah Zarco. My mom 416translated it for me into Yiddish when she gave it to me, because my Ladino wasn’t so hot. But I didn’t keep her translation. I left the ghetto kind of fast. I only took the jewellery that my grandmother Luna, Rosa’s daughter, had instructed me to keep.’

‘What jewellery – you never said anything about that?’

‘I had an old topaz ring with me, but I used that to pay a bribe for a Polish smuggler to get me safely to Piotr’s apartment. And a pair of sapphire earrings. I managed to hold on to those. You’ll figure out who gave them to me – and why – when you read the scroll. Everything else I might have inherited had to be sold to pay for food and clothing. And for sawdust for those crummy stoves we had. Bah! Anyway, just before I crawled out of the ghetto, I tied the scroll around my belly so it couldn’t get lost. Rosa had told me and my mom that it was a powerful talisman. It got a little creased and sweaty.’ He grimaced. ‘It picked up my lice, too. But those little monsters died a long time ago, Got tsu danken. A word of advice, Eti – don’t ever get lice!’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘And tell George and Pi and Violet too, because lice are no good.’

‘I’ll be sure to tell the kids. So what’s the manuscript say?’

‘It’s got to do with those strings of mine.’

Dad had developed a theory that everything that’s ever happened was joined together by fine filaments of cause and effect that we can’t normally see. He called them the Incandescent Threads, because he said they gave off a warm light, at least to those with mystical vision enough to see them.

Once, when I had the flu and he was trying to make me forget how bad I felt, he told me in a conspiratorial whisper that he’d seen them twice. The first time was when Shelly and Uncle George found him after the end of the Second World War. ‘Two faint threads of light stretched from George and Shelly to me, and they 417were glowing red, and I tried to touch them, but that only made them vanish,’ he said.

The second time he saw an Incandescent Thread was while walking through the Alfama district of Lisbon with my mother on their first trip to Portugal. He was exhausted from the plane flight and the uphill climb past the cathedral. He’d closed his eyes to rest, and when he opened them, a filament of curving, highly charged vermilion light made his eyes tear. It had issued from the base of a crumbling old wall.

Dad grew convinced that the seemingly unimportant spot must have had something to do with his ancestors. Maybe it was even where Berekiah Zarco had lived.

Now, I asked, ‘Why didn’t you tell me about the Waldbaum’s box before?’

‘Because I don’t like the idea of you carrying the extra weight of what happened to me. My past … We both know that it’s too much at times. So only read the manuscript later, when I’m with Mom. Hey, remember when we went out to Utah and first met George’s parents?’ he said to change the subject.

‘Of course,’ I said.

‘Weren’t they wonderful people? George’s grandfather was a powerful shaman, you know.’

‘Yeah, he and his dad told me about animal spirits when they took me hiking in Canyonlands National Park.’

My father smiled at me, and I could tell he wanted to say something important, but he also didn’t want me asking too many questions.

‘Go ahead,’ I told him. ‘I won’t make you go back into the past.’

‘Good. Listen, Eti, Shelly’s things are there too.’

‘Where? In Moab?’

‘No, in the metal box – in the basement. The stuff he left for 418me is in one of the pink boxes they’d give us at the Seven Dwarfs Bakery for a chocolate mandelbrot.’

‘I was wondering where you’d put his things.’

‘Diane knows not to let anyone go near them without my permission.’

Diane was Shelly’s youngest daughter. She’d been living in Dad’s house for the last eight years. She worked in Manhattan as a travel agent and also served as a guide on tours through Spain and Portugal three times a year.

‘I know you think I’m crazy for all this secrecy,’ Dad said.

‘Nah, I just think you’re you.’

‘Good.’ He gazed off beyond me. ‘To tell you the truth, kiddo, I don’t even know what crazy means anymore. So many words seemed to have shed their meaning of late. Even when I’m jabbering away to myself in Yiddish, I stop sometimes and think, That word used to be big and round and important, and now it’s just … just a microscopic little nothing, and I haven’t any idea what the hell it’s supposed to mean.’

I Found Them Spooned Together in Bed

Shelly lived with us for the last three years of his life. At first, he didn’t want to leave Montreal and the memories residing in every corner of his house, but Aunt Julie had died and his daughters couldn’t take him in since they both travelled so frequently. Uncle George offered him the guestroom in his house in Moab, but Shelly thought that Utah was too far away from his daughters and Dad. Our only other choice would have been a nursing home.

My father suggested we move another twin bed into his room, so that’s what we did. But Dad’s tapes of Mom singing kept Shelly up at night, so we moved him into the den. I gave him his own 419portable computer with a big flat-screen monitor and taught him how to watch NHL games and old movies, my son helped him find some pretty good porn sites, and he had his own door to the garden and a small refrigerator, so after a few months of moping around dejectedly and a couple of nasty quarrels with me and my father, he settled into a happy routine.

Dad would go to Shelly’s room every night before bed and they would split a shot glass full of Danziger Goldwasser, which I wasn’t supposed to know about, but I found the bottle under his bed when I was straightening up his room one day. Sometimes the two cousins would fall asleep in their chairs. Once, about six months before Shelly’s death, Dad must have grown too tired to climb upstairs to his room and I found them spooned together in bed, with my father’s arm over Shelly’s chest.

I got my sketchbook and drew them quickly, but I haven’t yet framed it. I’m not yet ready to see all I’ve lost so clearly. Maybe I never will be.

To Create Something Beautiful

What Shelly loved most was sitting with Benni in the backyard, on one of the quilts that Belle sent my mom, his eyes shaded by his Boston Red Sox baseball cap, sipping coffee drizzled with rum and reading classic French novels or gossiping in Yiddish. Before his bad hip limited his mobility, he also joined Dad as one of Angie’s assistant gardeners.

It always used to make me laugh to see Benni and Shelly covered head to toe with dirt and carrying trowels in their hands and asking Angie what she wanted them to do next.

Angie in her blue sweatpants and yellow sun hat, leading the two old men around the garden and pointing with her gloved hand to the overgrown bedding around our apple trees or the circle of tulips 420they’d planted the previous autumn … ‘Time to get serious about weeding,’ she’d tell them as if they’d been shirking their duties.

They adored being ordered around by Angie – you could see it in their eyes. And working in the garden meant they could still help to create something beautiful.

During his final years, Shelly had a problematic liver, and he often suffered with bronchitis, as well – undoubtedly from seventy years of smoking two packs a day. Whenever we had to put him in the hospital, he also developed what his physicians called hospital psychosis and would become pretty loony. Often, he’d whisper to me and Dad that the doctors weren’t really doctors and nurses weren’t nurses.

‘So who are they?’ I asked the first time it happened.

‘Spies.’

‘For which country?’

‘I’m not sure. Maybe Russia. In any case, they aren’t who they say they are, so be careful.’

Once, when he was in the Intensive Care Unit, Shelly told me of a representative of the Polish secret police named Wieczorek who’d visited him that morning and pretended to be worried about his health. ‘The schmuck even brought me a prune hamantaschen and thought he’d trick me into eating it in front of him!’ Shelly told me. When I asked what he meant, he motioned me close to him and whispered cagily, ‘It smelled of rat poison, so I told him I’d save it for later and then tossed it in the garbage.’ Dad later told me that there really was a Mr Wieczorek, but that he wasn’t – as far as anyone knew – in the secret police. In fact, he’d been the owner of their favourite neighbourhood bakery. After the end of the Second World War, in May of 1945, Ewa had left her name and address with him, and he’d promised to give that information to any relations of Benni’s who returned to Warsaw. But a few weeks 421later, when Shelly arrived in the city and spoke to Wieczorek, the baker didn’t tell them that Dad was living with Ewa. ‘We never found out why he held back that information,’ my father told me. ‘He was probably terrified that Shelly and George were spying for the Americans and being watched by the Polish secret police. Though Ewa … She thought there was a different explanation. She said that Wieczorek told her he disliked Jews. So maybe he even hated us so much that he didn’t want us to find each other.’

On another occasion when Shelly was delirious – or when I presumed he was – he told me of a mirror that bled whenever a Jew was murdered, anywhere in the world, and that he had smuggled it out of the ghetto. I didn’t believe him, of course, though I would later find out that he was telling me the absolute truth – at least as he understood it.

The Affection in My Father’s Eyes

Uncle George visited Shelly, Dad and me for the last time in early April of 2010. He and Uncle Martin had adopted three kids, and his eldest granddaughter – Irene – escorted him on the flight to Boston from Salt Lake City.

George waved both hands at me the moment he spotted me in the terminal. His arms were pale and frail-looking, and his long grey hair – his ‘coyote’s tail,’ as Dad called it – was gone. A man stretched too thin by accumulated troubles … That’s how I began to think of him, because he’d had a cancerous tumour removed from his gut half a year before, and subsequent to the operation he’d been in bed with pneumonia for two months.

As Irene led him forward, I felt as if I were standing outside in a rainstorm, chilled and alone, watching a disaster slowly come to pass. But on the way to the parking lot, George gave me a hearty pat on the back and told me to cheer up. ‘I look like hell, but I’m 422okay,’ he said. I didn’t entirely believe him, but I also didn’t want to intrude on his privacy.

George was wearing a bolo tie of Kokopelli – the trickster god who’s always playing his flute – and after I put the bags in the trunk of my car, I told him it was beautiful.

He took it from around his neck. ‘Yes, it’s very fine work,’ he said, and he handed it to me.

The curved, high-shouldered figure was made of silver inlaid with brown-veined turquoise, and the flute was mother-of-pearl. On the back was etched the initials HB.

‘Henry Bizaadii – my uncle,’ George explained. ‘Dad’s younger brother.’

‘Wow – I didn’t know you had a silversmith in the family!’

I started to hand it back, but George shook his head. ‘Listen, Eti, I want you to have it,’ he said solemnly.

‘No, I can’t accept it. It must mean a lot to you – it was made by your uncle.’

‘Which is why it would please me so much to see you wearing it.’

I continued arguing, but he told me I’d dishonour him if I refused his gift. After he’d helped me put Kokopelli around my neck, he placed his hand against my chest – an intimate gesture he and I had both learned from Shelly – and said in Yiddish, ‘Trog es gezunterheyt, Eti.’ Wear it in good health.

His gift touched me greatly, but on the way home I grew morose, because I remembered how Mom had given away her collection of scarves to Aunt Evie and Angie after she’d learned that her cancer had spread. George spotted me sneaking worried looks at him and said, ‘Hey, Eti, let’s have a good time together and not worry about things we can’t control. Okay?’

I limited myself to nodding at him because my voice was lodged in my chest.423

Dad and Shelly were waiting for us on the front stoop of my house. As I walked around the car to help George out of the passenger seat, Shelly got to his feet. His walk had become a fragile balancing act of late, but he tossed away his cane and rushed to us. He threw his trembling arms around his old friend and started kissing him as if he were his long-lost brother. Dad hung back, waiting his turn, so my uncle reached out while he was trapped in Shelly’s boa-constrictor hug and grabbed his hand and pressed his lips to his palm, and the affection in my father’s eyes was wet and shining.

After the three old buddies had hugged and laughed and cried – and after Shelly had a chance to kid George about his haircut – Dad grew dizzy from all the emotion, so I sat him on the stoop again and instructed him to put his head between his legs, and after a while he could breathe without difficulty.

Irene had just turned nineteen, but she had a strikingly adult profile and reserved manner. Her eyes were deep with silent awareness – like dark ponds – and her face was framed by long ringlets of chestnut hair that reminded me of the nymphs and goddesses in Botticelli paintings.

Her expression turned panicky, however, while my dad was panting. ‘It’s okay, he’ll be fine,’ I told her. ‘It’s always like an Italian opera around here when your grandfather arrives.’ She still looked doubtful, so I told her to go around to our backyard to see our flower beds, and that I’d come get her and show her where she’d be sleeping in a little while.

Irene spent that night on a futon in the living room, then got picked up by two friends from college in the morning. They were spending their Easter vacation in the mountains of Vermont.

Around the dinner table on our first evening together, Shelly and George told Irene the story of their trip to Poland to rescue 424my father, who interjected zany asides about his life with Ewa. He got his biggest laugh when he told us that he used to drive Ewa bonkers by hiding slices of cake around the house and forgetting where they were until they started stinking of mould.

Talking about their mission of rescue seemed Shelly’s and George’s way of putting the world in order – of arranging the story of their lives together the only way that could make any sense. But they didn’t speak of the moment that they stepped out of their taxi and spotted Dad coming out of Ewa’s house. Years before, George had told me that it was a moment that could only be approached in silence.

All that he now said to his granddaughter was, ‘And then our searching ended, and everything else that would happen began.’

After dessert, Angie and I led George to the cot I’d put in Shelly’s room, and he thanked us for dinner. He and I hugged, and for just a second I seemed to scent the desert on him – the baking earth and sagebrush most of all, but also the endless, gravelly roads. That night, the eternal light of the Utah desert watched over the first of my many dreams.

Over our next five days together, I had little time with George alone, but on the sixth day, he took me aside after breakfast and told me he wanted to see my latest work. Uncle Martin had flown in by then – he’d been visiting his sister in Miami – so after breakfast, the three of us drove to my studio in Eagle Hill. I was nervous because the way George had always depicted Bergen-Belsen as just outside his front door or down the street had influenced me deeply and prompted me to put clues about my dad’s experiences during World War Two in my cityscapes of Boston. Of late, however, I’d become fascinated by the Greek myths – in particular, by the way they reminded us that there is a limit to how much of our destiny we can control. I’d started setting my favourite of those ancient 425tales in the intimate, chaotic and congested New York City of my childhood.

George’s knees were acting up, so he could only get around my studio with great effort. He didn’t speak as he hobbled over the paint-splattered floor, gazing at Persephone transformed into a flowering cherry tree in Washington Square Park and Helen of Troy abducted by Paris while waiting for a train in the 14th Street subway station, so Martin and I talked about a cottage that he was designing for a friend.

While observing George, I realised that my figures seemed too staged – as if they were trapped in a play I’d cast them in – and my shame became a prickly sensation at the back of my neck.

How is it that all our confidence can vanish in an instant?

‘Ah!’ my uncle exclaimed a little while later.

He’d picked up a small canvas that I’d turned to face the wall, since I considered it a failure.

In it, a naked man – bearded, powerful, with alluring, kohl-ringed eyes – is running with a sprightly little boy across a beach toward a dark-skinned, laughing woman standing on the shore. Behind them is an ochre-coloured cliff, and peering over the rim, crouching menacingly, is a giant wolf with red eyes and a bristling collar of silver fur. Around the angry creature are his masters – the soldiers of an ancient army. The boy is panting from exhaustion, and he has my father’s anxious black eyes. The dark-skinned woman, oblivious to the drama taking place behind her, has tossed a ball high into the cloudy sky and is preparing to catch it with cupped hands. To her side, at the water’s edge, is a slender boat with billowing sails. Across the windswept waters, a cavern of warm, ecstatic light is opening above a crescent-shaped cove.

I intended the fiery light to serve as a sign – from the world itself – that the man must seek safety in the distant cove, but I hadn’t 426yet found the right combination of form and colour to convey that message. A great deal else seemed wrong with the painting, as well, but especially the wolf, who was too obvious a threat.

‘I recognise your father,’ George said, ‘but who are the others?’

I told him that young man was Odysseus, though I’d been considering giving him Shelly’s face just before I stopped working on it.

‘And the woman?’

‘Nausicaa – daughter of King Alcinous and Queen Arete. I don’t know if you remember, but she makes it possible for Odysseus to return home to Ithaca and goes on to marry his son.’

He touched his fingertip to my dad’s face. ‘The sense of doom is upsetting,’ he said. ‘I think it could become a very strong work.’

His praise seemed to lift me out of a cramped, dimly lit corner of my mind. ‘Yeah, I like it too,’ I said. ‘In fact, I was obsessed with it for a while. But so much about it seems wrong. Anyway, I’ve given up on it for the time being.’

‘Listen, Eti, would you do an old Navajo Jew a favour?’ he asked, and when I agreed, he said, ‘Go back to it and finish it any way you like. And don’t quit, even if it takes years. All right?’

Leading Dad to Safety

Over the next few weeks, I worked on and off on the small painting, but without success until I added circular brushstrokes in silky pink and violet around the cove to give it the feel of a radiant eruv. And then, a breakthrough … I painted the wolf rearing up onto the prow of the sailboat, his back and stiff, upraised tail lit by the cavern of light in the threatening sky, staring at my father with keen, curious eyes. This positioning meant that he – the wolf – was in two places at once on the canvas: crouching atop the cliff at the left and on the boat at the right. Only a creature 427possessed of great magic could accomplish that, which made me eager to learn more about him.

While lying in bed that night, however, I realised that he wasn’t a wolf; he was Odysseus’s dog, Argus! He had tracked his master to the island of Scheria in order to protect him. And then – in a burst of insight – I understood why I’d painted him in two places at once.

To carry out my plan, I traced a black line down the centre of the canvas the next morning, and it was then that the real painting – the one that had needed me to give it form since the very beginning – came into being.

I created two vertical panels. In the left one, Odysseus carries my father on his shoulders and is racing together with Argus away from an enemy army toward the straining, anxious arms of Nausicaa. On the right, at a slightly later time, Dad, Odysseus, Nausicaa and Argus are all safely aboard the sailboat, making their way across the windswept bay to the light-blessed cove, to which I added sudden strokes of blue impasto to give it the feel of a protected refuge. The dog stands now with his front paws on the railing of the bow, and his wary gaze seems magical, since he is focused on the army gathering on the left-hand panel – in the past.

Nausicaa is now depicted as a lithe, cheerful woman with shimmering, boyishly cut silver hair – my mother just before the return of her cancer – but I’d decided not to identify Odysseus with Shelly or anyone else.

This was my first attempt to depict two different moments in time on the same canvas, and the juxtaposed panels drew my eye back and forth, which gave the composition more movement than any of my previous work. I was certain that I had happened on a way forward – and was so excited, in fact, that I couldn’t sketch or paint anything else for several days.428

I called the painting Odysseus and Argus Leading Dad to Safety. I began to think of it as an illustration in a storybook I might create of my father as a character in the classical myths.

I finished it six weeks after George’s visit, wrapped it up and shipped it off to him in Moab. In my note, I told him that I couldn’t imagine anyone else owning it.

He called me the day he received it to thank me. ‘I love your mom and dad in the ancient world!’ he said joyfully. ‘And the time change is perfect. And those amazing colours … It’s great, Eti. In fact, there isn’t anything about the painting that doesn’t seem just right to me.’

‘Did you know it was going to come out so good?’ I asked.

He laughed merrily. ‘No, my grandfather was the shaman in the family! But you know what? When an artist tells you he’s been obsessed with a work, it usually means there’s something in it that he needs to go back to.’

Just before we ended the phone call, he said. ‘One last thing – when did you decide to put yourself in the painting?’

‘Me? I don’t understand.’

‘Well, you seem to be playing Odysseus,’ he replied.

I felt as if something dangerous were stalking the phone line between us. ‘I don’t know what you mean,’ I said.

‘Listen, Eti, it’s only natural that you’d want to help your dad get to safety. All of us who’ve known you since you were little … We’ve always sensed how responsible you felt for him. But I never saw you illustrate your caring so clearly – your willingness to even go back in time and help him. It’s extremely moving.’

I knew he was right about my feelings, but what he’d found in my painting seemed a projection of his own affection for me. ‘Uncle George, I don’t know what to say,’ I told him. ‘I don’t think I’m Odysseus in the painting. I don’t look anything like him.’429

‘No, not now, Eti,’ he replied. ‘But you looked just like him when you were twenty years old!’

Kokopelli’s Mischief

What George told me left me stunned. And convinced that I might chance upon some surprising discoveries if I kept painting myself and Dad together.

Unfortunately, George never learned how he’d once again influenced my work; he died a little more than two months later, when I’d only just began my series of paintings depicting my father and me in Greek, Norse and Navajo myths. Uncle Martin called to give us the news. He said that the cancer had spread to George’s stomach just before he’d visited us. ‘Last night, he told me that it was time to end the pain, so I gave him an overdose of morphine. We’d stored up extra doses of it from our doctor in case we ever needed it.’

Martin’s choking voice took away all my thoughts. At length, I said, ‘That must have been the worst thing ever.’

‘I won’t lie – it was,’ he told me. ‘And you know what, Eti, saying goodbye … It was impossible for me. I tried to speak the words, but they wouldn’t come out. I held George in my arms, and he fell asleep, and then all of me seemed to go blank, but at some point, I realised I was shaking all over, and I fled outside. I needed to be alone, to escape myself and him – to get away from what we made together. I also think I wanted to test what being alone felt like.’ He gave a sad little laugh. ‘I didn’t like it at all. And it seemed all wrong – as if the world had made an error.’

Had George known he was nearing the end? When I asked Martin, he said, ‘Sure, but he didn’t want to tell you and your dad and Shelly. He wanted Kokopelli’s mischief and laughter to reign over the visit, not Death.’430

Maybe I’ve Lived Too Long

Shelly descended inside himself after I gave him the news. For several weeks, he hardly spoke, even to my dad, and there were many days when he wouldn’t even leave his room. I’d hear him pacing at all hours of the night. Whenever I came to him, it seemed that something wild with regret wouldn’t let him have a moment’s peace. Was it because he hadn’t been as kind and faithful a lover to George as he might have been? When I dared to ask him that, he pounced on me. ‘No, of course not! George and I worked all that out years ago.’

‘Then what is it?’ I asked.

In a misery-filled voice, he replied that he ought to have died before George and Julie. ‘I think maybe I’ve lived too long, Eti,’ he told me with his head in his hands.

Such a Beautiful Man

Two months or so after George’s death, Shelly’s daughters Monique and Diane finally convinced him to come outside and work with them in our garden. It was the late summer of 2010, and all the dahlias and freesias had just come up, and there was a lot of weeding to do. Once he started getting his big old hands into the soil, his interest in the world returned, and he started reading the newspaper again and taking Dad, Angie and me out to dinner at his favourite Mexican restaurant, and gabbing on the phone with his daughters nearly every day. After a while, he seemed to be his usual unstoppable self.

And yet there were times when he’d grow quiet in the middle of a conversation and his eyes would gain a faraway look, and he’d let his head fall, and I’d know he was thinking that there was no point in continuing.

Shelly had become forgetful over the previous few years, but 431about three months after George’s death, he started to exhibit more serious difficulties. Once, he started berating Dad in the post office for writing the wrong return address – my address – on a package that he was sending Diane for her birthday; he’d become convinced that he was still living in Montreal. On another occasion, when Angie dropped him at Schoenhof’s Foreign Books so he could look for French novels, she returned to him after doing a couple of errands and discovered that he hadn’t any money left to pay for the book he’d found; apparently, he’d handed over more than a hundred dollars to a young man who’d asked him for spare change.

Soon after that, Shelly grew plagued by the idea that something monstrous would happen to my father and that he wouldn’t be able to protect him. Dad did what he could to reassure him, but by then Shelly was way over his head in a sea of worries. Doctors suggested increasing his dosage of tranquilisers, and that helped a little, but it also made him drowsy a lot of the time.

Several days after his daughters came for a weekend visit, on the morning of November 18th, 2010, I went to his room to bring him his coffee, and I discovered that he’d stopped breathing. When I kissed him, his lips were cold. He was ninety years old – almost ninety-one.

Dad had convinced him to help him plant more than a hundred tulip bulbs in our front yard over the previous few days. They would come up in a few months, and their flowers would be pink and scarlet and purple, because those were colours Shelly picked out at the nursery, and that’s what started me weeping more than anything else.

‘He was such a beautiful man,’ was all my father said when I gave him the news, and he didn’t cry, but I read in his blinking eyes and lopsided smile that all his defensive walls were crumbling. 432

He collapsed a moment later. I caught him just before he crashed onto the floor, but he twisted his ankle badly.

I laid him onto the sofa in the living room. He was groggy and confused. I took his hands and told him he’d be all right. We didn’t discuss Shelly’s death. I tried to, but Dad closed his eyes and shook his head and whispered. ‘I can’t go anywhere near that.’

Shelly had indicated in his will that he wished to be cremated. Monique drove down from Montreal to Boston to make the arrangements. Then she, Angie and I drove his ashes up to Canada for the burial.

I didn’t want Dad to come with us – his blood pressure was erratic and his ankle was badly swollen – but he wasn’t about to let Shelly go back to Montreal without him. ‘Anyway, if I drop dead in the cemetery, there’ll be less work for everyone,’ he said. ‘You can just stick me in the ground like a dahlia bulb, with my roots facing down and stem facing up. Got it?’

‘Sure.’

‘But you have to put me right next to Shelly and Julie so that we can keep each other warm. The winters in Canada are too fucking cold!’

‘I thought you wanted to be put next to Mom.’

‘Well, that would be my first choice, but it really doesn’t matter. You can even send me out to be with George in Moab. I have it on good authority that geography doesn’t mean so much when you’re dead.’

‘Whose authority?’

‘My own. I’m old enough now to have figured some things out.’

I rented a wheelchair because Dad wasn’t able to put any pressure on his ankle.

After the ceremony, Monique hosted a gathering in her apartment, and it was moving to see how loved Shelly was by the 433nephews and nieces he had on Julie’s side of the family. Diane picked up deli food from Schwartz’s, but Dad couldn’t eat anything, not even the barley-and-mushroom soup that Angie and Uncle Martin insisted that he try. He asked me instead to make him pancakes with banana or whatever fruit Monique had in her fridge. ‘It’s the only thing I can keep down when my stomach is like this,’ he told us.

‘Only pancakes?’ I asked.

‘Yeah. It’s been like this for seventy years.’

When I showed him a questioning look, he nodded solemnly, which made me wonder if his gut had ever really recovered from the starvation he’d suffered in the ghetto. And I couldn’t imagine anything more generous and noble than how he’d always used clowning to cover up his fragility.

After Angie and I made my father pancakes with strawberries, Monique’s son, Daniel, who was fourteen years old at the time, read a eulogy that he, his mother and Diane had written. Dad looked down and hid his head in his hands the whole time. Uncle Martin stood next to him and kept his hand on my father’s shoulder.

‘Daniel spoke beautifully, don’t you think?’ I asked Dad as I wheeled him into the bathroom to wash his face.

‘Yeah, I guess so, but it wasn’t what he said that touched me.’

‘No?’

‘That little pisher … He turns on like a lightbulb in front of other people,’ Dad said excitedly. ‘And me, I was worried it would vanish. Just goes to show you!’

‘That what would vanish? I don’t get it.’

‘Shelly’s personality, kiddo. Danny has it. He loves performing. Which means it skipped a generation. Like your son, George. He has all my athletic skills. Not like you.’

‘Your athletic skills?’ I asked, since I wasn’t aware that he’d ever had any.434

‘It’s a joke, Eti,’ Dad said, snorting. ‘Now bend down.’

‘What for?’

‘Just do what I say for once!’

When I bent down, he adjusted my bolo tie of Kokopelli. ‘Much better,’ he said. ‘Now help me wash my face. It looks like a garden snail has been crawling over my cheeks.’

After Dad was all tidied up, Monique and Diane called us into the kitchen and handed him a bakery box tied with string that Shelly had left for him.

He’d written Benni on the front in Yiddish.

‘Dad left whatever is in it for you nine years ago,’ Monique said. ‘Just after the doctors found a tubercular scar in his lungs and we all got so worried it was cancer. He said to only give it to you after he was gone. But he sent us a letter to put in it just a few weeks ago.’

Dad sniffed at the box and made a face. ‘A nine-year-old mandelbrot is going to be pretty toxic. You think your father wants maybe to poison me?’

Monique and Diane didn’t realise Dad was kidding until he told them they’d have to eat it first, and that we’d wait a couple of hours to see they survived before having a piece.

I cut the string. Inside the box was a red velvet pouch in the shape of a heart that looked like something Shelly must have pilfered from a high-priced bordello. Inside it were Julie’s gold bracelet and Shelly’s wedding band, and a pair of diamond earrings. There was also a big white envelope containing five thousand Canadian dollars and a smaller one with a note written in Shelly’s jagged, Yiddish scrawl. Dad translated it for us:

Hi, Benni. If you’re reading this, it means I’m on my way to heaven. I really hope either Julie meets me right away or that angels know what to do with an erect cock and fine young ass 435(yes, I’m planning to get younger and a whole lot harder as I make my way into the Upper Realms). Otherwise, what the hell am I going to do every day? In any case, that’s not your concern. And George will be there to show me the ropes, so everything should be okay. You know what? I stashed this stuff away for you to give to your grandkids. I’ve already given my daughters enough for them and my grandson. You remember Berekiah’s Rule, don’t you? Mesirat nefesh and all that stuff about sacrifice … Anyway, you know I was never very good at writing, so I send a big kiss for Eti and lots more for his children. (Hi, Kiddo!) And I send you everything I ever was, because everything was what I wanted to give you and what you deserved. We had a good life, didn’t we? I mean, after that big unfair mess at the beginning. Gosh, what a great day it was when George and I found you! Or did you find us? I’ve never been sure which way your crazy Incandescent Threads were pointing that day. And then Julie walked into my shop and fell in love with me and put up with me all those years when I couldn’t keep my mischief-maker in my trousers. Whoever figured you and I would live together at the end? That was the cherry on top of the cake. Thank you for that and everything else. You know, despite all the tsuris, I got all I could ever have wanted. I see that now. What good fortune I had! See you soon! Love, Shelly.

Do You Have Lots of People’s Voices Inside You?

After Shelly’s death, I used to check on Dad a couple of times a night to make sure that he was sleeping, and sometimes, if he was awake, I’d go in and we’d sit together without talking, holding hands. If he was upset, I’d challenge him to a scrabble game and let him use the dictionary for help.436

Once, after I tucked Dad back in and went back downstairs to the kitchen, I felt as if Shelly were with me, so I whispered to him, ‘I miss you a lot.’

This was a little more than two years ago, in late February of 2016, and I knew I was mostly pretending that Shelly was with me. And yet a few weeks later, I was lying on the sofa, taking a nap, and I heard rustling sounds in the kitchen. I thought that a field mouse had snuck inside again, since we’d had problems with them of late. But as I sat up, I felt an unseen presence standing by the window, watching the snow, which was falling so slowly and endlessly that it seemed like a metaphor for all that remains just beyond our reach. And then I saw Shelly’s reflection in the window, and he was young again, with his dark good looks and seductive eyes, and he grinned at me and said, ‘Your father is eating bran flakes from the box.’

‘Is that you, Shelly?’ I asked.

‘Who else could it be? You know, Eti, your father eats cereal with his hands all the time of late, but only when you’re not looking. I think he’s becoming a kid again.’

When Shelly grinned, his scent of rum and cigarettes wafted over to me. I jumped up, and that’s when I opened my eyes and realised I was still lying on the couch and that I’d been dreaming.

I went to the window and opened the curtains and confirmed that it wasn’t snowing.

When I went to the kitchen, I found Dad sitting at the table in his pyjamas, with a glass of orange juice and a box of bran flakes, and he was eating them out of his hand.

Of course, I had probably figured out what my father was doing while listening to the rustling sounds. Yet I also couldn’t shake the feeling that Shelly had returned for a moment, in a world where the snow fell with feathery slowness and ghosts could be reflected in windows.437

‘You caught me!’ Dad said, and he held up his hands like a captured bank robber in a Western. ‘Don’t shoot!’ he pleaded in a quaking voice.

‘The last thing I want to do is play sheriff,’ I said. ‘So you can put your hands down, Dad.’

‘I’m not Dad, I’m Billie the Kid.’

‘Yeah, sometimes I’m pretty sure that you think you’re only about twelve years old.’

‘Eleven, more likely.’

He didn’t need to add that he was that age when his parents disappeared. He held up the box. ‘Want some?’

‘Sure.’

I sat down and he poured some into my cupped hands. I sipped juice from his glass, and we talked for a time about my latest paintings, and his eyes held mine with so much affection that I decided to sketch him.

‘But I look like hell!’ he said.

‘It’s just the bad lighting.’

He giggled. ‘If only it were just that,’ he said.

I started drawing his eyes, as I always do. If I can get them right, the rest of his face enters the tip of my pencil without much difficulty. Everyone who has ever met my father knows that he begins and ends with his dark eyes.

Like moonless nights, Mom used to say, and she was right.

‘You know, it was Shelly who told me that you like to eat cereal from the box,’ I said.

He banged his fist on the table, pretending rage. ‘Gone for five years and still ruining my fun! You can’t tell that man anything. If he were here, I’d give him a piece of my mind!’

‘Maybe you can,’ I said. ‘He told me just a little while ago, while I was napping.’438

‘I don’t get it.’

‘I was waking up out of a dream and he told me what the rustling noise was.’

‘He spoke to you?’

‘Yeah – and very clearly.’

Dad patted my hand. ‘That’s good,’ he said gratefully.

‘Why is it good?’

‘For one thing, he speaks to me all the time, so it’s only fair that he speaks to you too!’

I put down my sketch. ‘Have you seen his ghost?’

‘Listen, Eti, when people die … If we’re lucky, the best things about them stay inside us. We take over some parts of who they were. It’s how we go on.’

‘But what about his ghost? Have you seen him?’

‘No, but occasionally I hear him. And once, a few years ago, during the winter, I sensed him climbing into bed with me to warm me up. He was pretty drunk – I could smell the rum on him. We talked for a long time, though I don’t think it was really him. I think I was still half asleep. I guess my mind was inventing things for him to say.’

‘Do you have lots of people’s voices inside you?’ I asked.

He flapped his hand at me as if he were disgusted. ‘Too many! Your grandparents, old friends … Even parrots.’ He smiled excitedly. ‘Hey, did I ever tell you my cousin Abe had a parrot?’

‘Yeah, Glukl.’

‘But did I ever tell you how smart she was?’

‘No, I don’t think so.’

‘She could crack open almonds. And speak Yiddish and Ladino. She didn’t live in a cage either – she flew around the whole apartment. Abe was going to teach her to play chess, but the 439Nazis … They didn’t think that was such a good idea.’ Dad imitated Glukl’s croaking voice: ‘Fardrey zich dem kup und tu vos du vilst.’

‘What’s that mean?’

Playing up his Yiddish accent, Dad replied, ‘Don’t bother me, do vatever you vant.’

‘What colour was she?’

‘Green – a beautiful emerald green. But I think her claws were yellow. Is that right?’ He shrugged. ‘Yeah, I’ve got Glukl in me, and that sweet old hound that Belle loved so much. And there was a white cat with turquoise eyes that belonged to one of our neighbours back in Warsaw, and she made so much noise, you could’ve plotzed from the racket. You know what, Eti, it’s a fucking three-ring circus inside my head sometimes!’

In the End, We Won

Our worst crisis over the course of Dad’s last months happened when my son discovered that his grandfather had stopped taking his medications – a diuretic and statin, as well as a multivitamin. George was nineteen years old at the time and studying archaeology at the University of Massachusetts. It was late March of 2017, and my father had recovered almost completely from his minor stroke. His only noticeable after-effect was a slight trembling in his right hand.

I should have been able to predict my son’s reaction, since he was very close to my father, but an opaque layer of wishful thinking must have covered over the crystal ball in my head.

A shared love of reading and history had first brought my father and George together. Dad had started giving his grandson picture books on Egyptology even before he started kindergarten, and George would cut out the sceptres and necklaces with scissors, 440and he’d sleep with them under his pillow, which made us joke that he was going to become the first Jewish pharaoh.

Then, when the boy was nine years old, my father bought him an encyclopaedia-sized primer by E. A. Wallis Budge on the ancient Egyptian language that changed both their lives. Whenever my father would come for a visit, they would study together at the kitchen table, drawing the hieroglyphs and memorising both their phonetic value and their meaning.

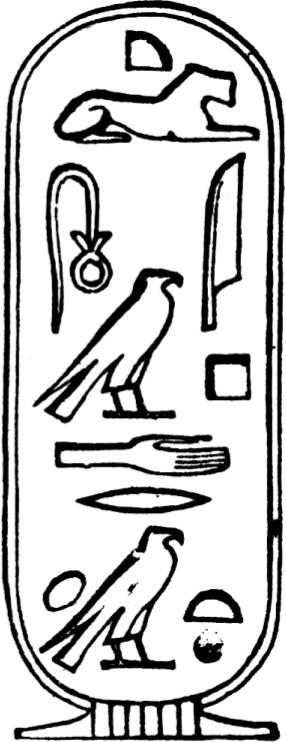

They began with Cleopatra’s name in hieroglyphs:

Dad never got past the first three lessons in Budge’s course, but George forged ahead with that unquenchable, optimistic energy of his, and by the time he was thirteen, he could decipher brief hieroglyphic texts in the extensive Egyptology collection he had on his bookshelves.

That same year, Angie and I took my father and our kids to the Metropolitan Museum and my oldest daughter, Pi – fiercely proud of her baby brother – asked him to tell her what was written 441in a framed scroll depicting Sekhmet, the Egyptian lion-headed goddess, and while I was listening to George’s translation, my dad went pale, and though he told me he was fine, he rushed off to the bathroom. After fifteen minutes he still hadn’t returned, and I figured that the Szechuan lunch we’d eaten had upset his stomach, but when I found him hunkered down in a bathroom stall, he said that while watching George and Pi discuss a battle that had happened three thousand years ago, he felt so proud of his grandchildren, and so happy that they’d been born, that he realised he’d beaten the Nazis – ‘Me and Shelly both!’

He said that his triumph had made him dizzy, but he didn’t want to take the spotlight off George, so he’d stumbled off to the bathroom. ‘And it’s all clean and polished,’ he said happily. ‘No bad smells. I’d give it an A. What about you, Eti?’

‘Yeah, it’s nice,’ I agreed, ‘but you could’ve said something to me. I’d have come with you.’

He shook his head as if it no longer mattered. ‘We won. Do you understand? Eti, we lost so many good people, but in the end, we won!’

I was about to help Dad stand back up, but a fancily dressed guy with a Spanish accent asked us if we were all right, and Dad said yes and told the man that his pinstriped suit looked expertly tailored, and that his white silk tie was a good choice, and my father asked where he’d bought it, and the Spanish guy said in Madrid, at a Corte Ingles department store, and Dad told him that he had an old tie that would looked great with the cream-coloured pinstripe and could he send it to him, and I started laughing to myself because of how my father could engage anyone in a good-natured conversation at any time, no matter where he was.

I took down the man’s name, and he said he was staying at the Hotel Carlisle, and the next day, Dad sent him a gorgeous 442rose-coloured tie that he’d cut and stitched himself more than twenty years before.

Dad’s closeness to George came as a surprise to me and Angie because when our son was a baby, my father’s clowning only made him cry. You never saw a kid who resented so fiercely any attempt to change his mood through diversion.

The boy hates me, Dad used to tell me with downcast eyes.

It took us both a long time to figure out that George required something of my father that no little kid knew how to put into words but that had something to do with the size and shape and nature of the world he’d been born into. I think now that what George would have told Dad if he could have found the words would have been this: I want you to be my storyteller, not my clown!

I suppose that some children know right away that they want a grandparent who can take them to faraway worlds – and into the distant past.

I remember the first time I knew that Dad had won George’s heart. My son must have been about five years old. Dad had him on his lap and was telling him about the big lazy ducks who spent hot summer days in the pond behind the house that belonged to Ewa, the piano teacher who’d saved his life.

‘You lived in Poland?’ George asked, as if it were impossible – even though, by then, I’d already explained about his grandfather’s background and showed him Poland on the map.

‘Yeah, I grew up in Warsaw. And I never spoke English.’ Dad spoke to George in Yiddish to demonstrate. ‘That means, the ducks are overheated and about to faint. And you know what, baby, if someone had told me that I’d have a grandson named after a beautiful Navajo man from Toronto, and that he’d grow up in Boston, and that his father would be an artist and a professor, 443and his mother a world-famous anthropologist, I’d have said that they were nuts!’

George’s eyes started glowing after Dad spoke to him in Yiddish. Dad later said that maybe my son spotted one of the Incandescent Threads that connected him to the small pond behind Ewa’s house or another of the places that had marked the lives of George’s ancestors.

At times, however, George’s extraordinary determination could morph all too easily into a belligerence that upset and confounded all of us. I remember that once, when he was fourteen years old, he had a French teacher who occasionally ridiculed the accents of his students, and around March he refused to keep going to class. I volunteered to speak to the school principal about his difficulties with the teacher, but he didn’t want me to do that. And when Angie and I pleaded with him to return to class and finish out the year, he stopped talking to us until we settled on a compromise, which was that he would switch from French to Spanish.

George remained close to my father throughout high school, and after he started college, he’d come home a couple of weekends a month to play scrabble with my father and take him to lunch at El Faro Taqueria, and amaze him with his stories about going to college in the age of iPods and smartphones.

So, as I say, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me that George would drive home right away when Dad told him he had gone off his medications, but it did. After a quick hello to me and his mother, he took the stairs two at a time and barged into my father’s room and apparently told him he was being selfish, and my father replied that there comes a time when an old man has to be a little selfish, and George said that he wouldn’t go back to college unless he started taking his medications again, to which 444Dad said that he wasn’t about to take orders from a little pisher, no matter how smart he was or how much he adored him.

I stayed downstairs, pacing in the kitchen, until George cried out that he hated my father. When I entered Dad’s bedroom, tears were rolling down George’s cheeks and his long brown hair looked a mess and he was fiddling with the piercing in his ear, which was always a bad sign. My father was seated with his head in his hands, trembling.

‘I’m never talking to him again!’ George told me.

Stay calm, I told myself, because I knew my son meant it. ‘George, come here,’ I said. My intent was to ask him very gently to apologise to my father for barging in on him and yelling. And then we’ll all sit together to work this out, I was planning on saying.

Maybe he sensed what I was going to ask because he crossed his arms over his chest as if he were preparing for a long war and said, ‘What do you want me to do, Dad?’

His defiant brown eyes told me I’d get nowhere with him, so I said, ‘Listen, why don’t you go to your room for now and let me talk to Grandpa alone? Okay?’

‘No!’ George declared. ‘He’s going to die, and he doesn’t care. He doesn’t care what he’s doing or how I feel about it or … anything else. He’s selfish – a selfish old man!’

Dad’s eyes grew enraged. ‘If you knew all I’d sacrificed to be here with you, you’d be ashamed to criticise me like that!’ he shouted. ‘Did you know I changed your father’s diapers for years, and made him dinners, all the time his mother was studying? And I was in my shop six days a week, scrounging out a living, because a lot of customers didn’t like it that I was on TV telling people that the war in Vietnam was sickening and wrong! And now … Now I just want a little peace and quiet.’ He took a panting breath. ‘All the damn pills aren’t going to save my life, George. Don’t you know 445that? I’m eighty-eight years old! When in God’s name do I get a little time off for good behaviour?’

My father’s face was so inflamed that I feared he was about to have another stroke. I went to him and took his hands. ‘Dad,’ I said, ‘just calm down.’

‘You calm down!’ he snarled, and he tugged his hands away.

‘We’ll get through everything together,’ I said. ‘All we need to do is—’

I wasn’t sure what I was going to say, but I never got the chance. ‘Eti, no one can request certain things from another person,’ he cut in. ‘It’s not fair.’ He looked at George and said in a pleading tone, ‘You can ask me a lot, but you can’t ask me to take medications that make me feel like shit. I want to feel good and strong for whatever time I have left. I want to eat chocolate mandelbrot and drink schnapps and make myself pancakes with egg yolks in the batter. And if I want to, I’ll even smoke a cigarette! Christ, why do I have to fight my own grandson? Can’t you understand how that makes me feel?’

George started crying harder – had he figured out that his grandfather was right? – then rushed out of the room. I told Dad that I’d handle George and to please calm down, but I had no idea what I was going to do. Back in the kitchen, I sat my son down and talked to him about how being old isn’t easy, and that my father missed Grandma and Shelly every day, and that because he had been confined during the war it was very important for him to decide his own destiny now, but I could tell from the rigid set of my son’s jaw that I wasn’t reaching him. Was he simply too young to understand? When he stood up and told me he didn’t want to talk any more about it, I realised I’d lost him. ‘All I ask is that you sleep at home tonight,’ I told him. ‘I don’t want you driving back to college alone when you’re so upset.’446

George nodded his agreement, but while Angie and I were talking about what to do, we heard him starting his car, and by the time I got to the front door, he was zooming off down the street, and when I called his cell phone he wouldn’t answer.

Dad and George didn’t see each other or speak again over the next five weeks. I’m pretty certain I suffered more than both of them, since they at least had their anger to sustain them.

‘Maybe they’re too alike,’ Angie kept telling me.

What she didn’t need to add is that I wasn’t like either of them – because I was pragmatic and conciliatory by nature. My mother used to say that I’d inherited Grandfather Morrie’s thoughtful and sensible, easy-going outlook.

In early May, George came home for a week before driving out to the West Coast with friends. He’d cut his hair short and put a second stud in his right ear. His face had become too slender and austere for my liking – he’d studied nearly non-stop for his exams over the last week – so I was glad he was going on a vacation.

I thought I might have a chance to broker a truce with my father, but he wouldn’t come downstairs to have lunch with his grandson. And when I asked George to carry my father’s dinner up to his room, he refused. Angie pleaded with him later that night to share a glass of schnapps or Danziger Goldwasser with his grandfather before bed, thinking that treating the young man like an adult might soften his heart, but he refused.

The second morning, when I brought Dad his breakfast, I asked him to lie – to tell George that he’d gone back on all his medications.

‘What would your mother say to that?’ he demanded.

Had my father read my mind? In fact, I was doing what I believed she’d want me to do.447

‘She’d say that it was a practical solution,’ I replied. ‘And that lying in this case wouldn’t do anybody any harm.’

‘No, she’d say that I had to be honest. That I couldn’t hide things from our grandson.’

‘I think you’re wrong about that.’

‘Have you forgotten how frustrated you’d get when I’d keep things from you?’ he asked.

‘It’s like this, Dad … I don’t want George living out the rest of his life knowing that he failed you right now. He won’t be able to make that up to you or me once you’re gone. And I can’t let that happen. I’m his father and I can’t let that happen! Do you understand?’

Dad frowned at me. I went to the window and surveyed the neighbourhood. Imtiaz, our across-the-street neighbour was mowing his lawn. Next door, the Palermo family’s overweight Shetland sheepdog was snoozing on the front stoop with all four legs in the air.

‘That can’t be comfortable,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘Goldie is sleeping with her legs in the air.’

Dad got up and stood next to me. He put his hand on my shoulder. ‘I used to sleep like that,’ he said. ‘It’s nice. It’s like your legs are weightless.’

‘When did you sleep like that?’

‘When I was a dog.’

‘And when were you a dog?’

‘Hard to say – I couldn’t tell time or read a calendar.’

I laughed, and Dad did too. I kissed him and he patted my belly.

He sat back down. I could tell from the way he was rubbing his chin that he was trying to decide what to do. I kneeled next to him, 448and I was going to ask him again to lie, but he started combing my hair with his soft old hand, and I started to cry.

‘Only for you, Eti,’ he said in a whisper.

‘Thank you, Dad.’

‘But listen, I don’t want to lie to him. I’m finished with lies. So if you get me a glass of water, I’ll take my pills.’

‘I’m sorry I had to ask this of you.’

‘I know. I’m sorry George and I quarrelled. I know that was hard for you.’

I got him water from his sink. He opened his drawer and took out his diuretic and his multivitamin. He downed them both in a single gulp. ‘Eti, I won’t go back on the statin. It gives me an irregular heartbeat, and I feel like I’m going to drop dead at any time, and I hate it.’

‘Okay, I understand.’

‘Now send up George.’

‘He might not come.’

‘Just tell him I’ve taken two out of my three pills. And that I never stopped my aspirin. Tell him I need to have a serious talk with him about what he can ask of me and what he can’t ask. And you can add that I’m going to beat his ass at scrabble!’

When I told my son that Dad had conceded to his wishes, he rushed out to the yard. When he came back in a few minutes later, his eyes were raw and red, and I said what I’d been wanting to tell him for weeks: ‘Love that doesn’t cross bridges isn’t really love.’

‘You mean I should have given in?’ he asked.

‘I mean that you should have met your grandfather halfway. We have to be generous with the people we really care about – always.’

He nodded, but I wasn’t sure he believed me. To make myself clearer, I added, ‘Love also forgives.’449

‘Which means?’

‘You need to forgive him for not being able to live forever. And he needs to forgive you for loving him so much that you forgot to be kind.’

He nodded solemnly, and when he passed me to go upstairs, he kissed my cheek. I didn’t eavesdrop on the conversation he then had with my father, but about an hour later, I knocked and went in, and they were playing scrabble at Dad’s card table.

‘I’m killing your little nothing!’ Dad said in triumph.

‘Only because you cheat so badly!’ George protested.

‘Eti,’ Dad said, ‘I’ve always been allowed to use the dictionary, right? It’s part of the rules because English has never really fit inside my head. Go ahead, tell him!’

‘I’m afraid Grandpa’s right,’ I told my son, as if testifying before a judge.

While they continued playing, I sat on Dad’s bed and started the Willa Cather novel – One of Ours – that he was re-reading. After a while, I closed my eyes, however, so that I could feel what a blessing it was to be able to stay in the room with my father and George without having to say anything. It felt right to have them forget I was even there.

Invisibility has always seemed to me a great blessing.

Near the end of the game, my son started looking over at me, and in his eyes was a dark, dangerous territory he was afraid to visit, and I knew that he was asking me for help.

At that moment, I also sensed that his secret had – through some complex adolescent process I didn’t understand – become tangled in his grandfather’s refusal to take his medications. That was what had made him behave so ruthlessly!

‘Go ahead and tell him,’ I said while Dad was adding up their scores.450

As George looked between me and my father, the boy stuck the tip of tongue between his lips, which meant that he was frightened.

‘What wrong, Georgie?’ Dad asked.

‘He’s got something to tell you,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘It’s … it’s kind of really important,’ the boy stuttered.

‘Is something wrong with you? Is that why you went so crazy on me?’ Dad picked up a scrabble piece in his hand and squeezed it in his fist. When George didn’t reply, he turned to me. ‘Eti, he’s not ill, is he? Tell me he’s okay!’

‘No, George isn’t ill.’

Dad got to his feet. ‘And Violet and Pi? Is something wrong with them?’

‘No, they’re okay.’

My father looked at my son for an explanation. The boy gazed down in embarrassment, then looked up at me with pleading eyes.

‘George is gay,’ I said.

Dad shouted back, ‘But what the hell is the important thing he’s got to tell me?’ He faced George, who was looking down again, and threw the scrabble piece at him, which hit the boy’s shoulder. ‘You’re giving me a heart attack! Now tell me what’s so important?’

‘I’m in love with a guy I met at college,’ George said. ‘I’m going with him on vacation.’

‘And you’re not ill?’

‘No, of course, not.’

Dad dropped down next to me on his bed, and when I put my arm over his shoulder, he started sobbing. George stood up, stunned by the depth of his grandfather’s reaction. After a little while, my father dried his eyes and opened his arms to my son. ‘If you don’t come here and hug me,’ he said threateningly, ‘I’m 451going to scream so loud that the police will come and arrest you for terrifying a helpless old man!’

After they’d embraced, Dad held my son away and smiled. ‘George, honey, I’ve known you might be gay since you were a kid. It didn’t matter then and it doesn’t matter now.’ He laughed in a burst. ‘Your Uncle Shelly slept with half the stevedores in Algiers before he met Aunt Julie. And it was Uncle George who taught him how to love. And I had my experiences with men too – including Shelly.’ He tapped George on the head. ‘I guess I should have told you that. But I figured it was personal. Anyway, you’re old enough to hear all that now, and to understand what I want to tell you, and it goes something like this …’ Dad closed his eyes for a moment to find the words. ‘Your heart and my heart and your dad’s heart … They follow the same laws as the earth when it goes around the sun, and the same laws that govern the yellow and orange growth of the tulips in our garden, and the same laws that control the way everything in the universe is attracted to everything else – which we usually call gravity. So you know what, I could never be ashamed of you falling in love with a boy, just like I could never be ashamed of the stars in the sky, or the squirrels in our garden, or the blue jays at our feeder.’ Dad looked up at me. ‘Could you be ashamed of a tulip, Eti?’

‘No, of course, not, Dad.’

‘George, we have to appreciate the beauty all around us – and be thankful, and grateful, that we share the world with flowers and stars and squirrels.’ Dad combed the hair out of my son’s eyes and kissed his brow, then looked up at me. ‘Oy, he’s too skinny, Eti,’ he said, playing up his Yiddish accent. He patted my son’s belly and asked, ‘Vood it kill you to eat a little more?’

George leaned forward and kissed my father on the lips.

Dad covered his eyes with his hand and started crying again. I 452hugged him until he pointed to his throat, which meant he was too dry to talk, so I got him a glass of orange juice from downstairs. After he’d taken a couple of sips, he said to my son, ‘Now tell me about this boy you’ve met.’ He held up a threatening hand. ‘But if you ever scare me half to death again over nothing, boy are you going to get a smack!’

The Perfect Moment

Dad died six weeks after making peace with George. Toward the end, he had crippling back pain that confined him to bed, but he absolutely refused to go to the hospital. George flew home from San Francisco to be with him and the rest of the family.

My father’s physician told me that the back pains might indicate lung cancer, which terrified me. But my father took the news with a shrug. ‘If that’s the costume the Angel of Death wants to wear, that’s okay by me.’ He motioned me closer and whispered, ‘What he doesn’t know is that I’ve got prescriptions for all the painkillers I could ever want!’

Only much later did it occur to me that my father might have suspected lung cancer for some time and had hidden the symptoms from me and Angie. Maybe he’d gone off his medications in the hopes of hastening a more comfortable death.

Dad died at home, with a jumble of Gershom Scholem’s books on his bed, one of Mom’s interviews with Belle playing on his tape player, his bottle of Danziger Goldwasser on his night table, and a game of scrabble with George waiting to be finished on his card table.

The last thing he said was, ‘You’re going to have to cut my toenails. They’re making holes in my socks, kiddo. And despite the rumours to the contrary, I can’t bend over that far.’

I’d just come into his room to check what he wanted for lunch, and I told him I’d be right back with my nail clippers. I decided to 453make him some fresh coffee, too. I sent it up with George while I went to pee.

‘Dad, you better come upstairs!’ my son called out a few seconds later.

My father’s head was turned to the window, as if he’d dozed off while watching the blue jays making a racket in our cherry tree. But his eyes were open and they weren’t focused on anything in this world. Face up on his belly was his photograph of the perfect moment in which his smile is so genuine and filled with delight.

After I took the coffee from George and put it down on the night table, I felt for a pulse, but it wasn’t there, so I kissed Dad’s eyes and closed them, and then I pressed my lips to his and kept them there until I thought I might be able to separate from him without screaming, because I didn’t want to make George any more upset than he already was.

When I stood up, I told Dad that I was just going to fetch Angie and that I’d be right back. I spoke aloud because he’d told me that a person’s soul sometimes hangs around his body after death, and maybe I didn’t really believe that, but I also didn’t want to risk him getting scared that I was leaving him.

George was trembling. His shoulders were hunched and his hands were frozen. I took them in mine and said, ‘Grandpa’s soul might still be with us, so talk to him while I fetch your mom.’

When I returned to the room with Angie, we discovered that George had moved a chair right up to his grandfather’s bed and was lying with his head on his chest. He’d pulled my dad’s arms around him, as well, and he was telling him about the hummingbirds he’d seen in San Francisco.

When George looked at me with lost eyes, I felt as if I were choking. And yet it was a comfort to know that he wouldn’t have to go through his life thinking he’d disappointed his grandfather 454just before his death. If I never accomplished anything else in my life, at least I’d done that.

A little later, I combed Dad’s thinning hair back over his ears and said, ‘Go to Mom and Shelly whenever you’re ready. I’ll be okay, and the kids and Angie are going to be fine too.’

Then I went to the phone and called my daughters. They both lived just outside Boston and had been to see my father the evening before, but they were working today. ‘Grandpa simply stopped breathing,’ I told each of them. ‘He wasn’t in any pain.’

I did my best to sound at peace when I spoke to them, but a terrifying silence surrounded me every time I stopped speaking, and I realised I was living now in a world in which I’d never be completely at home. And that I didn’t want to be there.

I fought despair as best I could that day and the next, but my father’s funeral down in the New York suburbs bested me, and it quickly became the worst day of my life. My heart felt like it was beating somewhere below the muddy ground of the rain-soaked cemetery. I have no idea what I said to anyone that day. My voice was coming from a cheerful impostor I’d invented so I didn’t have to speak of having to live the rest of my life without my dad.

Angie protected me. She hooked her arm in mine and walked me everywhere I needed to go. What I had ordered written on Dad’s headstone was this: