Have you ever watched teenagers playing an intense video game—yelling and cheering, high-fiving each other over a clever play or strategy? Surely you have observed teenagers texting their friends while standing in a tight circle, heads down and giggling?

The focus on technology by children today is so unwavering that most adults are frustrated by it. How often do you hear parents saying, “Put the phone down,” or teachers warning students to “put the phone away before it is confiscated”? Yet most adults have watched in awe as toddlers pick up their parents’ cell phones and play digital games. As adults in a generation that had to learn technology, it may be difficult sometimes to understand these children who are growing up with technology in every facet of their lives. Their brains have become wired to learn how to use technology with little or no instruction.

Now imagine schools where students are engaged in learning every subject because they want to, not because they have to. You would witness students collaborating about the subject matter in important and meaningful ways. They would be testing hypotheses involved in hands-on projects using the latest technology tools—that is the picture most people imagine when they are asked to envision the ideal classroom.

Ask those same people to paint the picture of the actual classroom today and it will likely be very different. The traditional teacher-centered method of instruction is often depicted as students sitting in rows of desks while reading textbooks and taking handwritten notes about the topic. Most assessments are given in the textbooks publisher’s format to all students, perhaps utilizing Scantron standardized tests, and then students wait a few days to receive their scores. Sometimes, the test is not returned for students to see what they got wrong and, more importantly, why their answers were wrong. Consider the famous classroom scene from the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (“Anyone… ? Anyone… ?”), and you get the idea.

The two scenes representing a traditional teacher-centered classroom and a technology-rich, student-centered classroom are two widely different approaches to learning the same subject. The challenge with school today is not the content being taught but the manner in which it is being delivered. The difficulty for most educators is finding a way to deliver curriculum content packaged in a digital wrapper. Student-centered, technology-driven learning has become a major cornerstone of digital-age education. Readily available technology delivers access to global resources and supports educators in addressing the wide-ranging needs of their diverse learners. Technology-assisted instruction provides resources far beyond the means of traditional classroom instruction by enabling students and teachers to access and share multimedia information. However, while all of this opportunity exists, accessing and utilizing it requires time and money—two things most schools and teachers do not have in excess.

The depiction of most workplaces today is not far from the vision of the ideal classroom. Most companies are moving to become paperless, making their data entirely digital, with all information produced and received electronically. Emails are the norm as a means of communication, serving as an efficient productivity tool; and video conferencing and telecommuting replace the need for long commutes and expensive travel arrangements. Clearly, most organizations recognize how the incorporation of technology enhances productivity. The natural evolution of education, then, is to follow the example set by the workplace by providing highly advanced technological tools not only for learning but also for the development of learning through technological avenues. Technology integration in the classroom empowers students by engaging them with the very technological sources and tools that will ultimately prepare them for employment in their future workplaces.

Our technology-rich world is not limited to just the workplace. There is no question that this is an age saturated by digital media. The number of internet users has risen from 2.6 million in 1990 to 3 billion in 2014 (Murphy & Roser, 2016). Technologies such as tablets, cell phones, and video-game consoles are commonplace in most households in the United States. Computers have evolved to become faster, smaller, more visual, and more portable. From wearable technology like smartwatches to the “Internet of Things,” including such technologies as smart appliances, society has become entrenched with immediate data and responsive feedback. Our cell phones tell us when we have to be somewhere via alarms and calendar apps, and then how to get there via GPS technology.

Adolescents and teenagers are using technology in more ways than ever before. They are growing up equipped with multimedia tools that significantly impact the world around them. Home telephones and standard postal mail have been replaced by the virtual world of cell phones, which are not only easily accessible but typically come with chat, text messaging, instant video conferencing, and email functions. Students no longer have to wait to go to the library to research a topic in the printed sources that are physically available there. The internet, with its many search engines and online libraries, makes data obtainable in an instant. Moreover, resources are not limited to those published by select sources. Knowledge can be accessed from people and sources all around the world. The time of waiting for the development of photographs and being unable to edit them is also gone. Today, students have the ability to make and edit their own photos and videos at little cost and with great ease. There are currently 1 billion YouTube users and 8 billion Facebook videos per day (source, date).

Consider the future with the proliferation of drones and 3D printing. Using their cell phones to navigate, children can fly drones above the trees and view the world from a new perspective. Printing actual 3D objects will become as commonplace as printing reports once was. That which we could not accomplish due to physical limitations in the past is becoming a reality in the present. Modern technology makes things that once took a great deal of time and advanced knowledge instantly available to most people.

Does technology have the ability to drive a student-centered pedagogy? Numerous studies offer evidence that teachers require sufficient technological competency in order to drive pedagogical change and achieve maximum student learning (Guzman & Nussbaum, 2009; Higgins, Beauchamp, & Miller, 2007). The goal of effective technology integration is to successfully embed technology use in education in order to drive a student-centered, investigative-based learning environment. Simply buying technology and urging teachers and students to use it does not meet this objective. To determine the actual benefits of integrating any technology as conventional classroom equipment, one of the crucial questions to answer is whether or not technological engagement actually does promote student-centered education.

Not all teachers teach the same way, and in that same regard, not every student learns the same way. When learners attribute a feeling of pride to a specific subject, they are more likely to become intrinsically motivated to master it. Motivation is often construed to be the stimulus that incites students to complete a task—the reward, either intrinsic or extrinsic in nature. Motivation is generally considered to be that influence that inspires and encourages students to engage in and complete activities that result in meaningful learning.

The inclusion of drones in instructional activities ultimately yields an increase in student motivation and engagement. The use of robotics in general allows students to have concrete examples of how STEM concepts are applied and utilized in the real world. A short exposure to robotics can have a lasting impact on students to pursue complex careers that they may have never considered. This is important, as it is projected that the nation will have up to 8 million STEM jobs by 2018 (Langdon, McKittrick, Beede, Khan, & Doms, 2011).

Outside of education, the use of drones is growing—particularly in the workplace, where applications are no longer limited to military or police operations. Scientists, construction workers, realtors, first responders, sports teams, band directors, and many more professionals are finding the utility of these quad copters, fueling a demand that this technology will quickly become a staple for college and career readiness.

In schools, drones are rapidly expanding in use and versatility as well. In science and engineering classes, students are building drones and writing the programs to steer them. School administrators are utilizing the technology to create marketing materials for YouTube channels and websites, showcasing their school and grounds from a bird’s eye view. Sports programs enlist drones to record the action in the athletic fields below.

In the curriculum, drones present a possibility of a broad range of applications. Just to take a simple flight or to plan a route, students need to consider weight, height, angles, and speed. The key to the learning experience is to reinforce content knowledge with technology—in this case, drones. The drones grab the students’ attention and engage them in an activity as they apply and master the skills that they learned during instruction.

A key element of teaching with the drone is the concept of incidental learning: students become so completely engaged by the use of the drone that they are not focused on the fact that they are applying concepts from the course content. Incidental learning is the unplanned learning that occurs during instructional activities and can occur in social situations (Kerka & Eric, 2000). It can arise as a byproduct of another event, such as “an experience, observation, reflection, interaction, unique event, or common routine task” (Konetes, 2011, p. 7). And incidental learning has a long tradition, with evidence dating back to decades when intentional and incidental learning could occur simultaneously during the same instructional activity (Cohen, 1967).

Children will spend countless hours in front of a screen, trying to accomplish missions in a video game that has no reward other than the value awarded to it by the player. As students, however, these same children may have difficulty finishing homework, paying attention in class, or finding a reason to be interested in a lesson. When students perceive the use of drones as an enjoyable activity—as an act of play as opposed to a learning activity—it can be a powerful motivator, impacting student enjoyment of the lesson (Carnahan, 2012). In other words, the problem is not always in the child; the instructor has to find a way to properly motivate the learner. The inclusion of drones as an application of concept is one way to do this, providing the hook that many students need to be engaged in the lesson and actively interested in learning.

Compared to most other technology, drones have the ability to gain and hold student attention in a unique way. Almost every student wants to fly a drone, and even if they are not actively controlling it, their attention is on it while it is in the air. While students make no differentiation between formal or incidental learning, the unintended outcomes of an incidental-learning experience often have a greater impact on the learner than the original lesson objectives (McFerrin, 1999).

Incidental learning is reported to show an improvement in self-confidence and self-determination, for instance (McFerrin, 1999). This aligns with the use of drones to get quiet and introverted students collaborating and communicating during group activities. Teachers have reported that students who never speak will take part in group work and even answer questions to the whole group when drones are included in the teaching method or lesson.

The inclusion of drones also allows teachers to differentiate the lesson and reach students who may not be not be interested in the subject matter. Putting the focus of activity on the drone while applying mathematics concepts during the flight times creates the perfect conditions for incidental learning. And gaining knowledge that is a product of incidental learning includes positive outcomes like a greater retention of information than that of the traditional lecture (Younes & Asay, 2003). The use of drones goes beyond simple instructional benefits and concept mastery because it impacts student engagement, communication, collaboration, and other important classroom components.

Teachers will enjoy the benefits of increased participation in the classroom and the real potential to impact the non-observable affective elements such as self-confidence. Anecdotal experience has shown that interactions with technologies such as drones and robotics can also have long-term effects on students who want to continue their interest in STEM-related fields. Children often desire more interaction with drones and robotics, and thereby evolve their use into more advanced skills. The use of drones and robotics may just be that spark that inspires certain students to change their life trajectory or career choices.

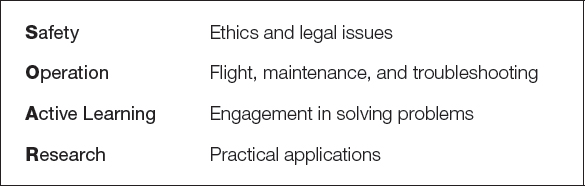

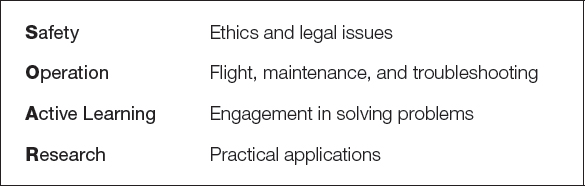

Dr. Chris Carnahan and Dr. Laura Zieger, two of the authors of this book, have created a drone implementation model for educators looking to establish a drone program in a K–12 setting. The SOAR (safety, operation, active learning, and research) model is meant to provide a framework for educators looking to not only learn more about drones but ultimately implement them in an instructional setting. SOAR is focused on the user experience while providing research-based foundations for ethical, legal, and pragmatic utilization. Figure 1.1 outlines the SOAR model and its components.

Figure 1.1 The SOAR implementation model for drone usage in a K–12 educational setting

The SOAR model has been the basis of numerous successful district and school-level implementations. The approach takes the time to ensure that a holistic approach is taken to cover all the relevant aspects of the technology and its integration into schools. Too often in education, technology is funneled into classrooms without proper vetting and thorough evaluation of its effectiveness. Just because a technology is flashy does not necessarily mean that it will promote learning.

The use of drones engages, motivates, and inspires students to learn in ways that no other technology will allow. This alternative to traditional instruction easily grabs the students’ attention, but safety must be a first priority. You must ensure the well-being of the operator, students, and institution. There are many considerations when operating the drones—especially outdoors—and uninformed operators present a potential liability to both the students and the school. It is crucial for users to be knowledgeable about all safety aspects to avoid potentially harmful situations.

Operation is concerned with the actual mechanics involved in flying and maintaining the drone. In the classroom, teachers may be without assistance, so they need to know how to safely fly the drone and how to quickly resolve minor issues. Comprehensive training on the classroom’s drone will make the instructor feel comfortable using the device with students. Additionally, having a basic level of problem-solving skills for issues that occur with the drone (such as connecting the drone and controller, or inspecting and repairing a damaged blade—shown in Figure 1.2) will minimize any impact that these events have on instructional activities. With limited instructional time, it is especially important that teachers be proficient with their drone to ensure safety and maximize the educational impact.

Figure 1.2 Operators should be familiar and comfortable with inspecting a drone and replacing parts.

Active learning is another critical component of using drones in the classroom. The concept of active learning can be defined as “anything course related that all students in a class session are called upon to do other than simply watching, listening, and taking notes” (Felder & Brent, 2009). Classroom utilization features a technology that engages students and inspires them to energetically participate in lessons. Whether the drone is used to collect information, demonstrate concepts, or hook students’ attention, it will be clear that students are immersed in the lesson.

Research is an often-overlooked component of technology deployment. Technology changes at such a rapid rate that traditional research generally lags behind adoption and implementation. And this can cause problems, as the technology cannot be thoroughly vetted and best practices cannot be developed. A haphazard approach to technology leads to misuses, unforeseen issues, and a loss of time and money. The best approach is to follow the recommendations of researchers and leaders in the field who have successfully implemented the technology. An efficient implementation maximizes the return on investment, so take a holistic approach that examines policy, professional development, and ultimately, effective classroom utilization.

In 2015, students began taking the Algebra I PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers) assessment, which is aligned to the Common Core State Standards. New Jersey is the only state in the nation using the PARCC exams to make graduation determinations in 2016. Starting with the class of 2021, students may be required to pass the PARCC Algebra 1 exam in order to graduate. According to the New Jersey Department of Education (2013), “In the NJ School Performance Report, Algebra I course taking is highlighted as an indicator of college and career readiness because it remains one of the most significant early predictors that a student is capable of rigorous coursework, and is on track to graduate from high school and attend postsecondary education” (p. 8).

Startling recent test results have been a cause for alarm. In a recent report to the New York Board of Regents, three-quarters of New York’s high school students flunked the Common Core algebra state standards–based test in 2014 (Campanile, 2015). New Jersey schools did not fare much better; less than half of the students scored as proficient at every level on the math tests, and only 2% of high school students who took the Algebra II test scored as proficient (NJ State Board of Education, 2015). As a result, students in middle school are being introduced to algebraic equations and concepts earlier in order to prepare them for the more complex Common Core State Standards–based Algebra I. (The CCSS integrate algebraic concepts in earlier grades, making CCSS middle school math curriculum more challenging than the traditional curriculum.)

The New Jersey Department of Education is motivating middle schools to offer Algebra I as one of its college-and-career-readiness benchmarks. The current target is for 20% of all students in school to take Algebra I in eighth grade (Erlichson, 2015). As far back as 1997, the U.S. Department of Education found that students who take algebra in high school attend college at a much higher rate, with low-income students being three times more likely to go to college (U.S. Department of Education, 1997). Other studies further indicate that “[students who] successfully complete Algebra I often continue to pursue the study of high school mathematics that prepares them for college, while students who are unsuccessful in Algebra I find their path to success blocked” (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, n.d., p. 1). According to RAND and Ball (2003), “Without proficiency in algebra, students cannot access a full range of educational and career options, and they have limited chances of success” (p. 47).

One concern is that these middle school students will not be able to comprehend the subject at an earlier age. While there is research showing that students who take Algebra I in eighth grade are more likely to successfully attend college, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics warns that pushing students to take it before they are ready often leads to failure (Gojak, 2013).

Historically, middle school math was overhauled in the 1990s, when the concern was that the United States was lagging behind other developed countries. Algebra became a national goal. Eventually, concerns began to surface regarding teachers’ ability to teach the subject, leaving students underprepared. The Brown Center at Brookings Institution report “The Misplaced Math Student: Lost in Eighth Grade Algebra” illustrated that having more students take algebra did not necessarily mean they were learning. High-income students were getting private tutoring to help them along while lower-income students (with less means for private instruction) were failing (Loveless, 2008).

Achievement in STEM subjects is a ladder toward promoting equity for all ethnic groups and socioeconomic statuses by providing access to academic and career success. Further, it has become a gatekeeper for the less advantaged to access high-status and income-producing occupations. Hundreds of thousands of students across the country are ending their education without having the mathematical and science skills they need to be educated citizens and consumers.

Algebra is an essential subject to developing students’ ability to learn how to reason with facts; it is the building block for higher-level mathematics. Many of the concepts presented in Algebra I are progressions of the concepts that were introduced in Grades 6 through 8. According to the 2010 draft proposed for the New Jersey Algebra I Core Content, the mission is “[for] students to use mathematics to make sense of the world around them. They use mathematical reasoning to pose and solve problems, communicating their solutions and solution strategies through a variety of representations” (p. 1). The proposal further states, “Students studying Algebra I should use appropriate tools (e.g., algebra tiles to explore operations with polynomials, including factoring) and technology, such as regular opportunities to use graphing calculators and spreadsheets. Technological tools assist in illustrating the connections between algebra and other areas of mathematics, and demonstrate the power of algebra” (p. 1).

The Common Core emphasizes conceptual understanding at every phase of math instruction, including algebraic concepts. How can these abstract ideas and concepts be taught to students at the middle school level? Students in middle school should be drawing bar graphs based on experiences, conducting experiments, discovering and generating patterns, and following and writing directions for carrying out tasks. These students can then build their understanding of statistics, probability, and discrete mathematics based on these previous activities.

American K–12 students still fall behind other industrialized countries. According to a recent PEW report, at the age of 15, United States students ranked 35th out of 64 countries in mathematics (DeSilver, 2015). Unfortunately, the more abstract math becomes, the less students are interested. This is particularly pertinent during the middle school years, when teachers often have fewer options to explain abstract concepts. But technology such as drones, or UAVs, can help students understand the significance of a quadratic equation. By using UAVs, abstract math is brought to life through the power of visual and hands-on learning.

Essential conceptual questions that can be addressed by utilizing drones in the curriculum include:

• What are some ways to represent, describe, and analyze patterns that occur in our world?

• When is one representation of a function more useful than another?

• How can we use algebraic representation to analyze patterns?

• Why is it useful to represent real-life situations algebraically?

• How can change be best represented mathematically?

• How can we use mathematical language to describe change?

• How can we use mathematical models to describe change or change over time?

• How can patterns, relations, and functions be used as tools to best describe and help explain real-life situations?

• How can the collection, organization, interpretation, and display of data be used to answer questions?

• How can the representation of data influence decisions?

• When does order matter?

• How can experimental and theoretical probabilities be used to make predictions or to draw conclusions?

The United States National Education Technology Plan (NETP) supports the implementation of STEM-related teaching, indicating that technology should be used to support student interaction with STEM content in ways that promote understanding of complex concepts, engage complex problem solving, generate opportunities for STEM learning, and prepare for the future workplace. According to Dr. Chris Dede, the Timothy E. Wirth Professor in Learning Technology at Harvard Graduate School of Education, “Many, if not most, teachers in STEM fields will be hard pressed to get from industrial-style instruction to deeper learning without the vehicles of digital tools, media, and experiences” (2015).

As a result of the changing times, technology literacy has become a required skill for education professionals and their students to successfully participate in the current global economy. The International Society for Technology Education (ISTE) created the ISTE Standards for Teachers to align with their vision of what a technology-enriched learning environment should include. The standards promote the idea that teachers should incorporate diverse technologies in their teaching in order to best address students’ needs and provide creative lessons that engage learners.

According to ISTE, educators need new expertise and pedagogical understanding to “teach, work, and learn in the digital age” (source). The ISTE standards consist of five benchmarks for teachers: (1) student learning and creativity, (2) digital-age learning experiences and assessments, (3) digital-age work and learning, (4) digital citizenship and responsibility, and (5) teachers’ professional growth and leadership. The general focus of the standards is to cultivate the best possible conditions for success. Though teachers are expected to create a certain learning environment for their students, they are also compelled to model the example of lifelong learning themselves.

Keeping current with emerging technologies demonstrates to students that education is a never-ending journey. With robotics and drones becoming so prolific in society, the knowledge and skills required to operate and program UAVs is a necessary technological literacy.