Chapter 2

The Nervous System, Stress, and Relaxation

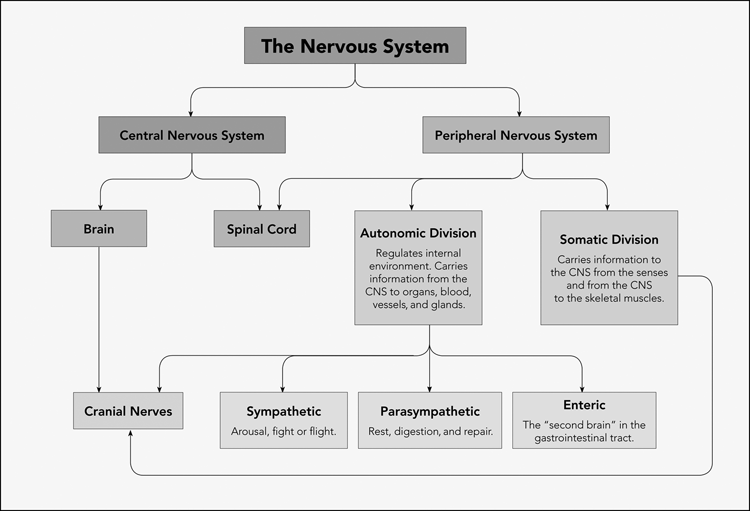

The biological entry point for our exploration of the koshas is the nervous system, our consciousness. The nervous system is the connecting and integrating link between body and mind, a vast network of communication circuits that coordinates the brain with all the other body systems, sending instantaneous electrical messages throughout the body. We receive information from the world around us, process it, and then choose to take action, all through the nervous system. It governs our heartbeats and breathing, our movements, and our body chemistry, but also our thoughts, intentions, and emotions. Unlike most of the animal kingdom, whose reactions to the environment are instinctual and repetitive, humans can make infinite choices, create art, and learn innumerable skills and ideas—all thanks to the sophistication of our nervous system. We can even learn to modify the functioning of our own nervous system, and this is the great promise of bodywork, meditation, and other bodymind modalities. I’ll give a few examples of some parts of the nervous system that characterize a typical day (a complete guide is beyond the scope of this book). This diagram showing the overall map of the nervous system is useful as a reference.

A Day in Your Life

You wake up and remember where and who you are, making the transition from sleep and dreams to alertness. That’s the reticular formation in your brainstem, telling you that you’re awake. It is the gateway for stimuli coming from the environment, helping you to respond with appropriate states of alertness or relaxation. We can sleep through city noise, yet awaken to a baby’s cry, because of the reticular formation. At night, when we lie still with our eyes closed, especially in a darkened room, the reticular formation signals the body to settle into repose. Other functions of your brainstem (which includes the pons, medulla oblongata, and midbrain) are regulation of your breathing and heart rate, and signals of hunger and thirst. In other words, it’s all about basic survival.

So now you’re awake and moving. You begin to feel and move your body. Now your peripheral nerves (connecting your brain to every part of the body) begin to report in, feeling the touch of the bedclothes, feeling the movement of your limbs as you start to get up. The peripheral nerves are of two types: sensory and motor nerves. The sensory nerves report sensations to the brain (traffic sounds, the smell of coffee, the brightness of light, the temperature of the room, the feeling of the floor under your feet), and the motor nerves stimulate the muscles to contract. Most of the time we’re not conscious of many of these messages, but it’s possible to become more attuned to them with practice.

Your cerebral cortex, the most evolved part of the brain, kicks in when you decide to get up. It organizes your intention, your sensations, your body awareness, and your knowledge of how to interact with your world. There are two hemispheres, or halves, of the cerebral cortex that coordinate with each other through a thick connecting band of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum. Despite the popular notion that the two hemispheres have different domains (the left for language and logic, the right for spatial awareness and creativity), we now know that it’s not that clear-cut; these functions take place in various regions of the brain. As you get up and walk through your house or apartment, both hemispheres are working together.

Once you are upright, your balance and coordination are governed by your cerebellum, which is just above the brainstem. You can consciously attend to balance by using sensors in your feet and all your joints, but a significant part of balancing takes place automatically in the brain.

The Nervous System

Perhaps now that you’re up, you’ll notice your overall energy level. Do you feel calm and quiet, making a slow transition to being awake, or do you feel stimulated to briskly start your day? This sense of the energy level in your mind and body is the function of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates your body and mind from moment to moment below the surface of your everyday awareness. The ANS’s functions include your heart rate, your blood pressure, and your metabolism.

The ANS has two divisions, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which are always in a balancing act with each other. When we’re resting, we are predominantly in the parasympathetic mode, often called the “rest, digest, repair” mode. When we are excited and active, we are in the sympathetic mode, also known as the “fight, flight, or freeze” mode.1 We fluctuate constantly between these two opposite ends of the energy spectrum, and those fluctuations can be as small as gently waking from sleep, or as large as responding to the sound of gunshots nearby.

I invite you to reflect on whether you tend to spend most of your day in sympathetic mode (stimuli, activity, maybe even anxiety) or in parasympathetic mode (quietness, rest, fatigue, lethargy, or depression). Or perhaps you are balanced: sometimes active, sometimes at rest. The yoga tradition gives a name to that third, balanced state—it’s called sattva guna, or harmony and clarity. The three gunas are said to be the three qualities of nature, and we can see any aspect of life through this lens—our work, our self-care, our relationships, our inner dialogue.2 The guna of rajas is the state of activity and excitement at one end of the spectrum, and the guna of tamas is the state of rest or inertia at the other end of the spectrum. One goal of yoga practice is to find access to the third state between the two extremes—sattva guna, or balance and harmony, on a regular basis. Not that you never get excited, or never sleep—of course life does and should have this whole range of qualities. But often we get stuck in one extreme or the other. Like yoga, Bodymind Ballwork can help to revive you if you are lethargic, and also calm you down if you are agitated, bringing you to the balanced state of sattva guna.

The Stress Response

Because you may be reading this book to learn how to reduce your stress, let’s look at the stress response in more detail. Stress is a fact of life, and in moderation it’s beneficial for our health. Stress can stimulate us to grow. But if it’s experienced in excess and is sustained over the long haul, it’s a whole other story.

Stress can be defined as anything that knocks our system out of basic homeostasis. Stress can come from overwork, from past or present trauma, from fear, from illness, from sleep deprivation—the list goes on. Hans Selye (1907–1982), a Hungarian endocrinologist, expanded our understanding of stress. He identified two different types of stress: negative stress, which he called distress, and positive stress, which he called eustress.3 He also identified three stages in the process of responding to stress, with different possible outcomes. The first stage is alarm, then adaptation or coping, then either resolution or exhaustion. We’ll discuss this more later.

The stress response starts in the part of the brain between the brainstem and the cerebral cortex called the limbic system, and it is here that we interpret sensory input and initiate a responsive action. Is this incoming message a sign of danger or not? The limbic system is said to be the brain’s emotional center, and it includes the thalamus (where sensory input is first sorted), the amygdala (our alarm system), and the hippocampus (our memory storage bank). The hippocampus compares the current moment to our past experiences in order to decide on the response we should take. (Note: there are other components of the limbic system, some of which I’ll mention later, and neuroscientists don’t always agree on what goes on the list.)

When we are faced with a challenge, either real or imagined, the alarm goes off in our amygdala. The body goes into red alert—a major activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Relatively minor daily threats might include preparing for an important meeting, trying to find your lost wallet, or worrying about a difficult situation that you have to deal with today. Or there could be a bigger threat to your safety, such as an oncoming vehicle in the road or another person about to attack you. Your hypothalamus (another part of the limbic system) instantaneously sends signals to the adrenal glands (a crucial part of both the nervous system and the endocrine system, in the middle of your body just above your kidneys), where hormones kick in to get you ready to meet the threat.4 One of those hormones is epinephrine, also known as adrenaline. Another one is cortisol, one of the glucocorticoid hormones. Epinephrine/adrenaline works in seconds to speed us up; cortisol kicks in more slowly over minutes or hours to return the body to homeostasis.5 With the adrenaline surge, blood flow is diverted from digestion and the skin to the skeletal muscles to supply extra fuel so you can act quickly and efficiently. Your heart rate and breathing rate increase to supply extra oxygen, passageways in the lungs dilate, and your mind shifts into a high alert state with the pupils of the eyes dilated.

Once triggered, the stress response lasts about twenty to thirty minutes, as long as the stimulus is not repeated. However, the perception of stress can last much longer, causing harmful chronic stress to the body and mind. Robert Sapolsky states in his book Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers that the stress response itself, especially if it is chronic and intense, is a detriment to health in many ways. Our stress response system gets used to being stimulated and forgets how to turn off.6 Excessive cortisol from long-term stress is correlated with cardiovascular disease, immune deficiency, poor tissue repair, sleep problems, impaired learning, mood disorders, and endocrine imbalances, just to name a few. One of the great gifts of bodymind practice is to provide balance to this chronic stress by enhancing our “rest, digest, and repair” states of being, which are the domain of the parasympathetic nervous system.

When we are exposed to threats over a long period of time, bodymind conditioning develops; the amygdala becomes habituated to a state of ongoing vigilance and anticipatory fear. This in turn conditions the muscles and fascia to be in a state of constant readiness and constant tension. To some degree, we all carry this kind of tension, preset from conditioning throughout our lives. The question is: Does it limit our freedom and our well-being? And what can we do to reset our nervous system toward more ease? Stay tuned.

The main function of the parasympathetic nervous system is to calm the bodymind after the stress of a sympathetic stimulus, to bring us back to homeostasis. All the changes noted above are reversed: the heart rate and breathing rate slow down, blood supply to the digestive organs increases, brain activity slows down, and the eyes relax.

The vagus nerve, one of the cranial nerves exiting the spinal cord near the base of the skull, contains a full 80 percent of all the parasympathetic nerve fibers in the body.7 Its name means “wanderer,” reflecting its winding pathway through many of our vital organs. New research on the vagus nerve promises to provide many new approaches to stress-related conditions such as heart disease, arthritis, and depression.

Vagal tone is the ability of the vagus nerve to regulate key processes in the body toward lower excitation. When the vagus nerve is stimulated by the hypothalamus to evoke a parasympathetic response, it will slow the heart rate and dilate the blood vessels. Gentle pressure on the eyes and their surrounding bones, as when using an eye pillow in restorative yoga poses, will elicit a parasympathetic response and increase overall relaxation.

I postulate that the sustained pressure of the balls, especially at the base of the skull, could help to switch the nervous system from stress to relaxation, strengthening vagal tone. Herbert Benson, a physician and the author of several books on wellness through effective stress management,8 popularized the notion that we can learn methods to make this switch as part of our normal daily skill set. Research is ongoing regarding the effect of vagal tone on inflammatory conditions, mood regulation, and social behaviors.

Your Breath as Regulator

Remember that the second kosha is the breath? The way we breathe affects the nervous system very directly. Each time you inhale, there’s a small stimulus to your sympathetic nervous system, and your heart rate speeds up a little. Each time you exhale, your heart rate slows down and your body shifts toward relaxation. This is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia. In addition, the upper lungs have more nerve receptors for the sympathetic nervous system, whereas the lower lungs have more receptors for the parasympathetic nervous system. Fast, shallow breathing speeds you up, and slower, deeper breathing slows you down, because when we inhale deeply, we reach those parasympathetic receptors. This is one reason why bodymind modalities emphasize the conscious practice of breathing deeply and slowly to focus and calm the mind. When the breath is steady and full, the mind and body become more calm and steady as well.

Navigating the Stress–Relaxation Spectrum: Challenge versus Threat

As mentioned above, we constantly fluctuate between sympathetic and parasympathetic dominance. With too much sympathetic dominance, we may be chronically agitated and then exhausted, whereas too much parasympathetic dominance can lead to lethargy and depression. Both external situations and internal thought patterns can trigger these responses; they can persist over time or change rapidly from moment to moment. The stress of jumping out of the way of an oncoming car can be physiologically the same as the stress of an intense argument, or the stress of attempting a challenging yoga pose, or the stress of anticipating anything that we fear. The difference is in our ability to distinguish between the excitement of a challenge and the fear of an injury.

Stress is beneficial and conducive to growth in appropriate doses (Hans Selye’s “eustress”). If we can shift cognitively to meet a challenge without seeing it as a threat (when appropriate, of course), the body responds with the quick-acting epinephrine, but without the overdose of cortisol.9 Here is one of the many delicate interactions between our thoughts and our physiology, inviting us to examine how we perceive our world and how that perception affects our health.

The sympathetic response is all or nothing (when stimulated, everything goes into red alert), but the parasympathetic system can be activated one portion at a time and has many “switches.”10 In Bodymind Ballwork, the steady pressure of the ball, the steady flow of the breath, and slow and steady movement all contribute to an overall composite switch toward parasympathetic dominance. And I have found that this effect gets stronger with practice.

Conditions for Relaxation

Here are some other ways to enhance relaxation when you are practicing the ballwork:

- Reduce internal stimuli (for example, avoid caffeine).

- Time your practice for best results. Notice your stress patterns throughout your day, and practice when you most need it.

- Limit your sensory input, which means being comfortably cool or warm, and having a relatively quiet environment.

- Consciously let go of muscular tension as much as you can.

- Breathe deeply and slowly.

- Concentrate on what you are doing, noticing your physical sensations, and gently guiding your mind away from worries, plans, fears, memories, etc.

- Practice regularly. Your bodymind will gradually retrain itself toward intentional relaxation when you need it. You’ll become conditioned to let go of mental and physical tension when you feel the balls against your body.

In the next chapter, we’ll look more closely at the connective tissue of the body, how pain is registered in the body, and how relaxation occurs from the pressure of the balls.