Chapter 6

Getting Started

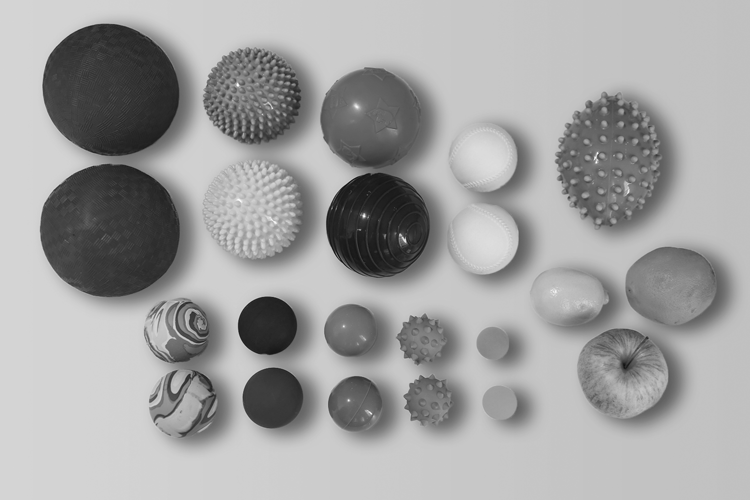

To get started practicing the ballwork, you will obviously need a few balls. Bodymind Ballwork is done with rubber balls in several different sizes to accommodate different parts of your body and to create different amounts of pressure. Larger balls work well in areas such as knees, neck, and hips, whereas medium-sized and smaller balls are needed for the spine, shoulders, arms, abdomen, ribs, and lower legs. The smallest balls work well for the head, feet, and hands. Some balls have a different texture (soft, medium, or hard when you squeeze them); some are hollow and some are solid. Many people ask if tennis balls will work, since they are so easy to find. Although tennis balls are better than nothing, they do not adapt to the body as well as rubber balls. You can begin with a basic set of balls, which can be purchased online or in toy stores. (See the About the Author page for ordering information.)

The basic beginning set is:

- Two large hollow balls (4˝–6˝, about the size of a cantaloupe) for the neck, upper chest, spine, and legs

- One football-shaped ball (6˝ long) for the neck, front torso, ribs, shoulders, and legs

- Two medium-sized hollow balls (3˝ or 4˝, about the size of a large apple or orange) for the neck, spine, arms, and legs

- Two small solid balls (2.5˝–3˝, about the size of a large lemon) for the spine, arms, and legs

- One small hollow ball (1.5˝–2˝, about the size of a small lime) for the face and feet

- One very small solid ball (1˝–2˝, about the size of a walnut) for the feet and hands

The ball collection with a lemon, an orange, and an apple at lower right for size comparison. Colors will vary.

As a historical note, these balls were used in the 1960s by world-renowned choreographer Trisha Brown.

In addition to the rubber balls, you’ll need a room, fairly quiet if possible, where you can lie down on the floor. A yoga mat is helpful, but not necessary. You should also have a blanket and pillow handy. If you have yoga props, include a yoga block.

It’s good to have about twenty minutes or more of uninterrupted time. But the most important thing you’ll need is your own permission to turn your attention inside and feel your body. With so much outward demand on our attention in the outer world of work, family, and the details of life, these conditions might be challenging. But once you develop a practice, it will become obvious how that time is well spent. Your connection with yourself will grow, making room for more self-compassion, self-understanding, and hopefully greater ease. If you have a meditation practice, you can think of ballwork as meditation with your body as the focus, and set your surroundings as you would for meditation. If you are not a meditator, you might want to choose some soothing music to help you to slow down and focus inward. You deserve this time for yourself, and it will pay off by helping you to be more present and fully available for everything else that you do.

Focusing Inward

Ask yourself: What am I feeling in my body right now? Perhaps the easiest sensations might be your body position and the awareness of what is touching your skin. If you are on the floor, you can notice which parts of the body contact the floor. This is called exteroception, or using the five senses of touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste to feel one’s relationship to things outside the body. You might feel the texture of your clothing and the floor or carpet, or sense the temperature or light in the room. Listen to the sounds around you. Exteroception also includes feeling the boundaries of your body: Where does the outside world actually begin?

Then, taking your attention further inside, you might feel the weightedness of the body or the movement of the breath. This kind of attention is called interoception, or feeling sensations that come from inside the body. Further development of this kind of sensing might involve noticing your general state of energy (relaxed, agitated, or something in between), your patterns of muscular tension, your digestion, your heart rate, even your patterns of thinking. There is a vast inner world to explore.

When we move, we are using a third type of awareness called proprioception. This is the feeling of movement, balance, and how the parts of the body arrange themselves in relation to each other. Using your proprioception, you might perceive whether your knees are bent or straight, or which way your head is turned. Proprioceptive sensors in the muscles and joints tell you when a muscle is being stretched, or when a joint is moving to its farthest range. Very slow and simple movements refine and expand your proprioception. As you enhance your proprioceptive sense, you will be able to move in a more coordinated, smooth, and efficient manner.

Every time you do ballwork, spend a few minutes first to tune into these modes of perception. Scan your outer and inner awareness as a place to start. Move a little bit to orient your perceptions to your feeling of moving. Taking time for this shift from outer to inner awareness is an important step in self-care. You are not only connecting to your physical self; you are opening to the subtle but ever-present interplay between the body, mind, and emotions. Thoughts, worries, memories, and agendas may arise. The emotions that arise might be anywhere on the spectrum from pleasant to unpleasant. This is all part of our inner experience, our inner being—no feeling is wrong.

Once you have attuned yourself to inner sensations and thoughts, you can choose a part of the body to work on with the balls. Then you can choose a technique to practice that will target that part of the body with certain balls and certain movements. In the chapters that follow, each technique is numbered and described separately with all the necessary details. There are several techniques for the shoulders, several for the spine, several for the hips, etc. I will describe the general contours of a practice session here as a preview, but please refer to subsequent chapters for specific instructions.

After placing the balls as instructed, there is a moment of settling and receiving the pressure from the balls. Take the time to feel how your body reacts, take some deep breaths, and release as much tension as you can. Let your body drape over the round shape of the balls. Then you begin to move, very slowly and gently, in a particular direction that is specific to that technique. It might be a movement of your arm or shoulder, or a movement of your ribs or hips. The slow movement combined with the pressure from the balls on the soft tissue (muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia) gives you the opportunity to feel that part of your body more clearly than you might have been able to feel it before. The balls dig in, and then as you move while maintaining the pressure, the balls create a shearing stretch in the layers of fascia and muscles inside. The result is happier soft tissue: less binding, better hydration and circulation, and freer movement range.

Information flows both ways: you are sensing and moving with more awareness than usual. Your movement and your perceptions inform each other. Each small adjustment of the body can be felt vividly, with the balls as a magnifying glass clarifying more details than one would in normal, everyday motion. Many students remark on this direct focusing quality of the ballwork. Some describe it as a kind of “depth probe,” a nonthreatening way to locate trouble spots in the body.

The weight of your body creates pressure between you and the ball that is similar to a massage. You can adjust the pressure according to your own needs and tolerance: a smaller or softer ball gives less pressure, a larger or harder ball gives more pressure. You may feel discomfort, even pain, in certain areas at first, because of the tension your body is carrying. People also often say, “It hurts, but it’s a good hurt.” Tight muscles and fascia may not give way to the pressure from the ball immediately. Tension in the tissues will set off pain signals in varying degrees of intensity, which should be noticed. If the pain is agitating you, choose a softer or a smaller ball, or practice on a bed, or adapt in ways that are suggested in the instructions. As time passes, the soft tissue does soften, and you will feel satisfying pressure, but not pain. This is why I recommend having a varied selection of balls to use, so you can change the pressure as needed. You will notice that some parts of the body respond well to more pressure, and in other areas, less pressure is better. This may change from day to day as well. I encourage you to use balls that you like, because that will help you do the practice!

Most techniques in this book require about ten to twenty minutes, and a few require up to thirty minutes. Be sure to end each working session with a few minutes of rest without the balls, which allows you to notice, integrate, and assimilate the changes that have occurred. Feel your body in the areas where the balls were, but also in other areas that might have shifted or released as well. This period of integration is an essential part of the process to develop and sustain meaningful change in your experience of your body.

The Principles

Principle 1. Develop Awareness without Judgment

For many people, it is a new experience to observe how their body actually feels from the inside, rather than how they think it should feel, how they are afraid it might feel, or how it felt yesterday. What is going on in this very moment? Observe with as much neutrality as possible; avoid jumping into the inner conversation that judges, analyzes, or reacts to what you feel. Value curiosity over achievement. You might notice that one part of the body feels stiff, another part feels comfortable, another part feels uncomfortable in a vague or specific sort of way, and yet another part you don’t feel at all. In this way, you can scan your body to see what your starting point is on any particular day.

Some of us have become accustomed to noticing only unpleasant feelings, perhaps because we take the body for granted when everything is fine. We specifically look for what hurts, or what is not working the way we want. We neglect to notice and enjoy what is feeling good. Unless something hurts, we feel “nothing.”

Others might suppress the aches and pains to avoid dealing with them; areas of the body with strain or fatigue become anesthetized. The entire range of sensations is worth noticing, because we can use that feedback to learn what the body needs. As we listen more to all the body’s messages, with some degree of objectivity, we are fine-tuning the bodymind connection and understanding ourselves more clearly. We are allowing sensations to surface that may have been censored because of pain, self-image, or assumptions or fears about the body. By being aware of the whole range of our sensations from the inside, we can make the best choices for our own health and well-being. I have found that people usually have reliable instincts. They might say to themselves: Yes, this is good for me, even if it’s a bit uncomfortable at first, or No, this feels wrong and I can either stop doing it or try doing it a different way.

Principle 2. Release into Gravity

We live in the field of gravity; it is our milieu and our dance partner as we move through life. In using the balls, gravity is definitely our ally. We invite beneficial pressure into a specific part of the body by releasing our weight into the ball and draping over it. We usually will not need more pressure than that. When you first place a ball under you or against your body, take the time to release into gravity and see what happens. That simple shift can create a major change in your inner state. Take a deep breath and let yourself become heavy.

When we are stuck in a state of generalized tension and stress, the fight-or-flight response keeps us poised to meet the challenge or to run. The nervous system can become so accustomed to that state that we live that way all the time. It is remarkably calming to simply let yourself become heavy and trust that the ground will hold you. With practice, you will become more and more skilled at releasing into gravity at will.

Principle 3. Move Slowly with Minimal Effort

Moving very slowly allows us to notice and feel more subtlety. It also shows us more clearly what is entailed in each movement. When we move at an ordinary speed, such as when pulling on a shirt or lifting a dish, it’s unlikely that we can separate the many different sensations that accompany the action; it becomes a familiar blur with perhaps only the end result being clearly experienced. Very slow movements, however, can provide a universe of discovery. We can feel which parts of the body move easily and which parts resist movement. We may notice that we prefer certain movements to others, and the slowness helps us to interrupt the automatic patterns and find new ways to move, ones that perhaps extend our range. One way to slow yourself down is to move just a quarter of an inch, then pause to feel, then move another quarter of an inch, and another, until you’ve reached a natural end point to that movement.

Along with this choice about the speed of our movements, we also have a choice about the degree of effort we use. In everyday movement, we tend to use a moderate amount of effort with occasional bursts of more intensity. While walking, lifting objects, or doing tasks, we let the body naturally recruit the “right” amount of effort. Daily life usually keeps us in the middle range of effort. When we touch another person sensitively or handle a delicate object, we might scale back to a lower level of effort in our movements. When we lift something heavy, we spontaneously recruit more effort. However, sometimes that innate assessment of effort becomes disrupted, and we overdo or underdo.

For this exploration, we take the premise that using less effort will help us to understand the actual requirements for any given movement and make more efficient choices. How little or how much effort does it take to move a shoulder? Can we let go of unnecessary muscles that move only out of habit? Once the movement is done, can we release the tension that we needed to move and really feel gravity’s power as it pulls our shoulder back to a rest position? You may feel the difference between moving by contracting the muscles and moving by stretching the muscles. You might also feel the difference between those times when movement is difficult and when it is easy, positions in which your body is working and those in which there is total rest. All of these discoveries will provide a closer connection between your analytic or intellectual mind and your bodymind, your conceptual self-awareness and your embodied self-awareness. With that connection, you have the skills to choose the right degree of effort for whatever you do.

As simple as they are, these slow and gentle movements may be frustrating to you, as they were to me when I began to do this work. Many of us are accustomed to moving quickly and without very much thought, or moving to create a certain visual or functional effect. The internal focus of exploring movement for its own sake may be a new experience, one that is fascinating and liberating.

Principle 4. Explore Your Range

Often in daily life, our movements are restricted to habitual patterns that we repeat over and over because they are functional. If you think about your daily life, you can easily think of positions and movements that are so familiar and frequent that you don’t notice how they feel.

When practicing the ballwork, you can have the intention to feel those ordinary movements more fully. For instance, when working with your shoulder, invite yourself to investigate all the different directions the shoulder can move. What does it feel like in the joint and the surrounding muscles when you raise your arm up overhead? When you initiate the movement from your shoulder blade, instead of from the arm or hand? When you move your arm across the body as far as possible? When you reach back? When you turn the arm in different directions?

Exploring in this way can reawaken pathways of connection in your bodymind and give you more range of movement than you thought you had. You’ll be filling in your body schema—the detailed but also unifying knowledge of the boundaries of the body, the movements you can do with each part, and how the parts relate to each other. You’ll see how each part moving affects every other part in some way. When you move your arm, your neck and torso will probably register that movement in some way. Every part is connected, and yet every part can move on its own. This experiential realization is very empowering, especially after an injury, when we might tend to avoid moving out of fear.

By narrowing the field of attention and focusing on a specific joint or area of the body, you can sense more details about how you move, and you can begin to recognize interrelationships. One student who had a shoulder injury told me, “When I began, I rarely moved my shoulders, especially my left shoulder, alone. My neck, even my back, wanted to get in on the act.” Her injury exacerbated a habitual movement pattern established at least in part by her work at her computer.

Moving one part of the body by itself is a skill that underlies a good, self-supporting alignment—that is, a balanced arrangement of each of the parts of the body in relation to the others. With sound alignment, you will have maximum strength and flexibility and be able to move easily, at will, with small adjustments exactly where and when they are needed to perform a particular gesture or task. This is the secret of good posture that allows safe, energy-efficient movement.

The Breath Is the Link

The breath is a natural—and useful—bridge between the mind and the body. Remember the second kosha, pranamaya kosha, the body of breath? Our breath continues without our conscious direction every moment of our lives, and yet we can choose to notice it and work with it. The intention to become more familiar and fluent with our own breath is an immensely powerful means of self-regulation. We can recharge when we are tired, or de-stress when that is what we need.

Sue, who is a pianist, noticed how much her sense of musical rhythm was influenced by her breathing patterns; when she was anxious, or concentrating on difficult passages, her breathing would be unsteady and her rhythm askew. With greater awareness of her breath, she was able to be steadier in her playing.

It is natural for such changes in the breathing to happen. In some cases, changes in breathing can be beneficial—such as when running for a bus or during childbirth. But sometimes the disturbance or change in breathing remains after its initial cause has passed. You can probably think of times when your breath was strained by an exertion, or constricted by anger or fear. Did it return to an easeful state after the stress had passed? Or was there a residue that remained?

While working with the balls, be aware of your normal breath, and allow it to adapt and shift as you explore. Notice the many possible qualities of breath. You might feel your breath as pleasant, nourishing, uneven, steady, fluid, restricted, or expansive. These are just some examples; observe what you feel, moment by moment. When you feel discomfort from the pressure of the balls, take a deep breath to aid the process of release and change. When the ball feels good, enjoy it and take a deep breath to savor that enjoyment! The spontaneous deeper breath that often happens as a result of using the balls is delicious, and marks an authentic connection to your true self.

The effects of working with the breath can be specific or general, dramatic or subtle. Your spine may lengthen, your shoulders and chest may relax, your voice may deepen, your mind may become clearer. Your whole body may feel lighter or heavier. Whatever the response, easier breathing always brings easier movement and a greater feeling of well-being, because the breath is quite literally a foundation of being alive.

Above All, Trust Yourself

Trust yourself to choose the right balls, the right parts of the body to work on, and the right duration of your practice. Trust yourself to gradually understand and integrate the process and the results. Doing the practice regularly will teach you how to deepen, how to expand, how to use it most fully for your own benefit. Trust your bodymind to reveal to you what you need to know for healing, for inner and outer realignment, for easeful movement and self-fulfillment.

The next chapters provide detailed instructions for ballwork techniques, addressing virtually every part of the body. Now that you’ve prepared yourself with knowledge of the basic principles of Bodymind Ballwork, you’re ready to get started!